Screening for adult disease

Principles of screening

Introduction

An entire population can be screened (mass screening) but more usually it is targeted at at-risk groups. Selection might be by age, gender or cardiovascular risk factors, for example (Box 6.1). Opportunistic screening involves a more random approach, such as screening patients who happen to attend a particular clinic.

Assessing the potential benefits of screening

Premature introduction of screening: Politicians can play a part in initiating inappropriate screening programmes. UK prime minister, Margaret Thatcher sanctioned nationwide breast screening in 1988, 2 weeks before a general election; some believe this was to garner the women’s vote. The decision was premature and based on insufficiently validated evidence from the Swedish two counties study and the UK Forrest report. In the 1970s, screening for cancer of the uterine cervix was widely introduced, also before its efficacy had been fully evaluated. Fortunately, it has proved successful despite the difficulty of engaging women at high risk. Sadly, the natural history of untreated dysplastic cervical cellular abnormalities was not properly established before the impact of widespread screening made this ethically impossible. This severely hampered scientific study of the disease, its early diagnosis and best treatment.

Criteria for assessing a screening programme: Many years ago the World Health Organization (WHO) realised that even beneficial screening could be expensive, unpleasant, inaccurate and unproductive, and could adversely affect psychological or physical well-being. In 1968, they published a list of criteria for effective screening programmes (Box 6.2) including attributes of the disease, the test and the treatment. These principles are still relevant today and have been added to by the UK National Screening Committee and other groups. Box 6.3 shows a summary of these modified criteria.

Evolution of screening programmes: Once begun, any screening programme must remain under constant evaluation and modified or discontinued when criteria are no longer being met. For example, in the 1950s and 1960s, screening for pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) by mass miniature chest X-ray was highly successful but it was disbanded in the 1970s when new cases fell below a level at which the unit cost per new case could be justified; interestingly, by then, the yield of new cases of lung cancer from screening began to exceed that of TB, but there was virtually no effective treatment for it at the time.

Criteria for an effective screening programme

The disease: The screened condition should be an important health problem either because it is common (such as lung or prostate cancer) or has serious but preventable consequences such as carotid artery disease or abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). The prevalence (proportion of cases already in a population) and the incidence (the proportion of new cases) of the disease in the population at risk are discovered from pilot studies. There should be a truly early stage where treatment outcomes are better than at a late stage. Colorectal adenomas and early cancers are good examples.

The diagnostic test: The test must be valid, i.e. reliable in detecting the disease. This is defined by sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity is the capability of the test to identify affected individuals in the screened population, i.e. the proportion of people who have the disease and are detected. A test with many false negative results is insensitive and unreliable. A UK appeal court ruled that sensitivity is paramount in (cervical) screening and awarded damages to women with missed diagnoses at screening. Specificity is the degree to which a positive test can be relied upon to prove the disease is present; in other words, the higher the false positive rate, the lower the specificity.

Diagnosis and treatment: Cases identified by the test must be amenable to effective, acceptable and safe diagnostic procedures and the potential benefits of medical or surgical intervention prompted by earlier diagnosis need to be understood.

Limitations of screening: Screening is conceptually and ethically different from usual clinical practice as the process is aimed at the whole population, and achieved by dealing with apparently healthy individuals. Participants expect the diagnosis of the presence or absence of disease will be accurate, and that if disease is found, the outcome will be favourable. However, there is no guarantee of protection because there will always be false positive and negative results, however good the test. Also, the disease may appear or progress unexpectedly rapidly between screenings. This emphasises the importance of good population education and properly informed consent for individuals engaging in the programme. Participating in screening must be a free choice and it may or may not have health benefits and significant adverse effects.

Participation rates: Universal participation is not usually necessary to achieve measurable community benefit and cost effectiveness. This is because community benefit is the sum of individual benefits (except for infectious diseases such as tuberculosis). If a validated screening programme has low set-up costs, benefits are usually proportional to costs. For colorectal cancer screening, for example, cost effectiveness falls off only at extremely low levels of participation.

Cost effectiveness: Imponderables such as the economic value of saving a life or extending survival need to be considered. All screening studies cost money in detecting and treating cases. The cost effectiveness of a screening programme is usually reported as cost per life year saved or the cost of increasing ‘quality adjusted life years’ (QALYs). The acceptable cost per life-year saved is a matter for debate; somewhere between £12 000 and £30 000 is often quoted as acceptable in developed countries.

Research benefits: Screening a population can teach the clinical community and the public much about the natural history and progression of a disease, its aetiology and its various associations, for example the link between abdominal aortic aneurysm and smoking. Different investigations and treatments can be trialled in large groups of affected individuals, to the ultimate benefit of the population at large.

Consent: Organisers are obliged to provide participants with reliable and unbiased information about the benefits and risks of any screening process and its consequences. There must not be any form of coercion to participate. Much current information tends to overemphasise the benefits of screening and minimises the risks, often not indicating that participation is voluntary. Breast cancer screening in the UK has been criticised in this respect.

Screening for cancer

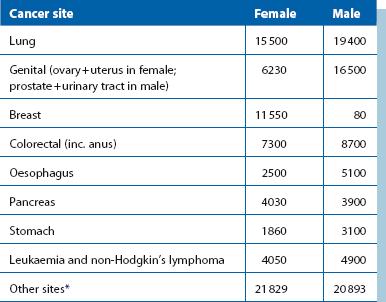

The common cancer killers are shown in Table 6.1, with bronchus still leading the field. Unfortunately, this disease does not fit criteria for screening, having no detectable early stage; attempts at screening have been uniformly ineffective.

Table 6.1

Most frequent deaths from cancer, UK 2010*

*Note that in males, three cancers—lung, prostate and bowel—account for just under half of all cancer deaths; in females, three cancers—lung, breast and bowel—also account for nearly half of all cancer deaths. Note also a large proportion of deaths occur where the primary has not been identified

Breast cancer

• Biologically early cancers—these include lesions too small to be detectable but with metastatic potential

• Small cancers and carcinoma in situ—these predominantly non-aggressive lesions may never metastasise

• Large or advanced tumours—these are usually symptomatic and quickly fatal

Large trials have concluded that as many as one-third of cancers detected by screening would never have presented clinically.

Effectiveness of mammographic screening: Mammographic screening every 2 years has been estimated to avert only 2 deaths in 1000 women aged between 50 and 59 over a period of 10 years. To achieve this requires 5000 screens and 242 recalls, and for 64 women to have at least one biopsy. Five women will have ductal carcinoma in situ detected, some of which may never progress to invasive cancer. Less than 1% of women invited for screening will benefit; a much larger percentage have to endure false alarms, unnecessary surgery and inappropriate labels of cancer.

The Cochrane view of breast screening: The Cochrane Collaboration is an international non-profit organisation that rigorously and dispassionately reviews published research evidence and provides up-to-date information about the effects of health care. Over 11 000 articles have been published in 20 years on breast screening. The Nordic Cochrane Centre reviewed all RCTs in 2001 and found that astonishingly few were of sufficient rigour to reliably determine whether screening reduced morbidity and mortality. Only seven RCTs were identified, of which only two were of sufficiently high quality. Evidence from the adequately randomised Canadian and Malmö trials showed screening had no significant effect. The other five trials, in which randomisation was inadequate, found that screening decreased the risk of death by about 25% but showed a slight increase in risk for screened women for death from any cause. A further Cochrane review was published in 2006, which reanalysed data from published trials. Both reviews found little benefit from breast screening and in 2006 they stated that the absolute risk reduction for breast cancer from screening was only 0.05%. They also found that screening led to substantial over-diagnosis and over-treatment. They concluded: ‘the currently available reliable evidence does not show a survival benefit of mass screening for breast cancer, and the evidence is inconclusive for breast cancer mortality.’ These controversial conclusions imply that breast screening does no good, causes actual harm and probably should be abandoned. This, however, is unlikely to happen.

Why breast screening is claimed to improve survival: Several factors could explain how screening could appear to reduce mortality, as follows:

• Lead time bias with over-detection of clinically insignificant lesions increases the apparent number of breast cancers. These cases do well

• Mortality from breast cancer can occur over a very long period; 35 years after treatment, the commonest cause of death in a Cambridge UK series was still breast cancer. Thus screening studies need to be prolonged

• Improvements in breast cancer treatment took place over the period of the main trials. Tamoxifen and perhaps improved chemotherapy undoubtedly extended absolute survival between the early and late 1980s. Over a similar period, other cancer rates fell for largely unknown reasons: thyroid cancer fell by 12%, testis by 17% and melanoma by 23%

• Subjectivity, unrealistic optimism and perhaps vested interests may lead to misleading presentation of statistics and unsustainable claims for the industry of breast screening

Other benefits from breast screening: Experience gained from breast screening and managing patients detected has brought rapid improvements in mammographic equipment, techniques and interpretation as well as a more sensitive approach to patients. It has generated much scientific study of the management of early breast cancer. All of this will eventually bring benefits for women with breast cancer and for people with other types of cancer.

Prostate cancer

• The epidemiology and natural history of the disease were ill understood

• Screening tests were inaccurate and staging was unreliable

• There was poor evidence of the effectiveness of treatment

• Little research had been conducted into the complications and quality of life after radical treatment

• On present evidence, there was no justification for PSA testing in primary care and there was insufficient evidence to support national screening

• PSA testing should be limited to symptomatic men, to monitoring prostate cancer treatment and to randomised trials investigating screening

Overall, PSA screening causes harm. Some men receive unnecessary treatment because the cancer is incurable or because it would never have presented clinically, and those treated risk infection (from biopsies), incontinence and impotence.

Screening for cardiovascular disease

Abdominal aortic aneurysm

Trials of AAA screening

The Danish study: A Danish study randomised 12 500 men of 65 and over to AAA screen or nothing. Of these, 75% attended and 4% had aneurysms. Screening reduced the rate of emergency surgery by 75% (CI: 51–91%); 59 were operated on electively with a 5.1% mortality. As regards cost effectiveness, 352 needed to be screened to save one life, 4 years after screening. The screened population was rescreened after 5 years: 30% of those with aortas 25–29 mm developed an aneurysm but none of those originally less than 25 mm did so. People with aortas of 25 mm or more diameter need periodic rescreening.

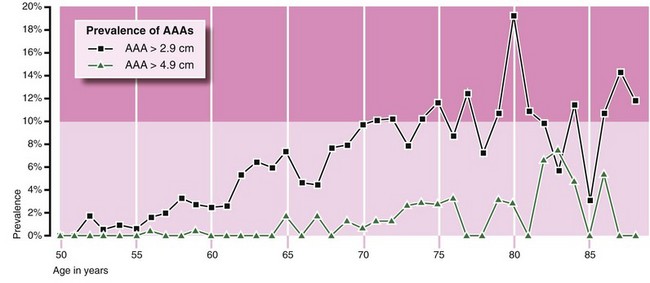

The Huntingdon study: In the Huntingdon study, 15 000 men of 50 and over were screened over 7 years: 540 were found to have an AAA larger than 2.9 cm, and 69 an AAA larger than 4.9 cm (Fig. 6.1). Very few small and no large aneurysms were found under the age of 60, an important factor when planning screening. Over the age of 70, there was virtually a 10% incidence of small AAAs. In this study, AAA mortality also fell by 75% and the number needed to be invited to save one life was 600.

Fig. 6.1 Prevalence of AAA in men over 50 in the Huntingdon Screening Programme

The graphs show the percentage of those screened found to have small aneurysms (black line) and large aneurysms (green line). Note that the lines are approximately parallel, suggesting that small AAAs become large AAAs some years later

The UK MASS study: Screening was undertaken in four centres and 68 000 people were randomised to screening or not, beginning in 1997. Some 98% of people in both groups were matched with national mortality statistics. After 7 years, 21% of men had died. There was a 76% attendance among those invited (27 147 were screened) and 4.9% had an aortic diameter of 3 cm or greater. All-cause mortality fell by 4% in those invited and there was a 47% risk reduction for AAA deaths in this group. The cost of screening and treating detected aneurysms was £12 500 per life year saved and no adverse effects were found on quality of life. The 30-day mortality for elective cases was 6%; for emergency cases operated upon, mortality was 37%. It was calculated that if screening were offered to a population, only 6% of AAA workload would eventually be on ruptures compared with around 30%. After 10 years, the relative risk-reduction of aneurysm-related deaths was still 49% (CI: 37–57%), the cost per man invited was £100 and the cost per life year gained was £7600. Thus the benefit of a single screen lasted at least 10 years, though the incidence of rupture rose after 8 years.