Chapter 63 Scoliosis and Kyphoscoliosis

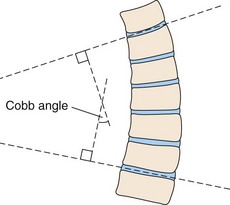

Scoliosis refers to lateral curvature of the spine (Figure 63-1), a well-recognized clinical entity that was described by Hippocrates as early as 500 BCE. Kyphosis indicates backward and lordosis forward curvature in an anteroposterior (medial) plane. Many patients who have a thoracic scoliosis are mistakenly described as having a kyphoscoliosis, because the rib angle prominence is misinterpreted as a kyphotic component. In fact, most instances of idiopathic thoracic scoliosis incorporate a lordotic and a rotatory element. The degree of lateral curvature is expressed by the Cobb angle, which is calculated from radiograph-based measurements, as shown in Figure 63-2.

Figure 63-1 Radiograph showing lateral curvature of the spine in a patient with congenital idiopathic scoliosis.

Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Pathophysiology

Spinal curvature is the most common cause of chest wall deformity. The causes of chest wall deformity are shown in Box 63-1. By far, the most frequently found scoliosis is the idiopathic variety, which accounts for approximately 80% of cases. Idiopathic scoliosis is defined as lateral curvature for which no cause can be identified; congenital forms of scoliosis are related to a developmental abnormality of the spine, as in failure of segmentation (e.g., fused vertebrae), failure of formation (e.g., hemivertebrae), or genetic syndromes (e.g., spondylocostal dysostosis or Klippel-Feil or Goldenhar syndrome).

Genetics of Idiopathic Scoliosis

Spinal curvature is acquired in neuromuscular disorders (Figure 63-3) that involve the chest wall and thoracic musculature before skeletal maturity occurs. Scoliosis develops in more than 50% of boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), and spinal curvature is common in many of the other congenital muscular dystrophies, myopathies, and conditions such as type I and type II spinal muscular atrophy. The introduction of steroid therapy in childhood in DMD may lessen the severity of scoliosis by reducing the rate of loss of muscle strength, such that wheelchair dependency occurs later in adolescence and peak vital capacity is increased, although the number of prospective randomized controlled trials has been limited.

Effects of Chest Wall Deformity on Respiratory and Cardiac Function

Lung Volumes

Although both scoliosis and kyphosis diminish lung volumes, which results in a restrictive ventilatory defect, lateral curvature has a more profound effect on chest wall mechanics. Total lung capacity is reduced in all chest wall disorders. In a pure scoliosis, both vital capacity (VC) and expiratory reserve volume are decreased, with relative preservation of residual volume (Table 63-1). An obstructive ventilatory defect is rare in scoliosis and kyphosis, unless the individual is a smoker, has coexistent asthma, or the scoliosis results in bronchial torsion.

Table 63-1 Typical Results on Pulmonary Function Testing in Patients With Idiopathic Thoracic Scoliosis

| Parameter | Effect |

|---|---|

| Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) | Reduced |

| Forced vital capacity (FVC) | Reduced |

| FEV1/FVC | Normal |

| Residual volume | Normal |

| Total lung capacity | Reduced |

| Transfer factor for carbon monoxide—diffusion capacity (DLCO) | Reduced |

| Transfer coefficient (KCO)—DLCO/accessible alveolar volume | Supranormal* |

* Transfer coefficient usually is supranormal, but it is reduced in the presence of pulmonary hypertension.

Lung Compliance

Gas transfer coefficient tends to be raised in patients with scoliosis in the presence of a low transfer factor (see Table 63-1), because extrathoracic compression squeezes more air than blood out of the lungs, thereby decreasing accessible alveolar volume.

Diagnosis

Monitoring High-Risk Patients

Monitoring high-risk patients should include the following:

• Assessment for breathlessness, exercise intolerance and associated limiting factors, frequency of chest infections, and symptoms of nocturnal hypoventilation

• Measurement of respiratory muscle strength (e.g., mouth pressures, sniff inspiratory pressure)

Additional investigations may be indicated:

• MRI scanning may be required to delineate spinal cord and vertebral anomalies, and computed tomography may be needed to investigate abnormalities such as pulmonary hypoplasia or bronchial torsion.

• Echocardiography (ECG) is mandatory in all patients with congenital or early-onset scoliosis.

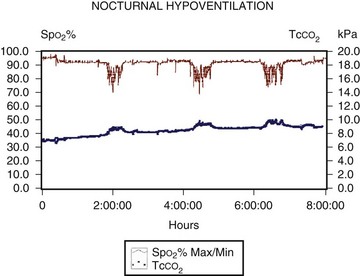

As noted, in addition to detecting breathlessness and exercise tolerance, the assessment should identify any symptoms of nocturnal hypoventilation (morning headache, poor sleep quality, frequent arousals, nocturnal confusion, and morning anorexia); if any of these is present, the patient should undergo monitoring of respiration during sleep. A characteristic picture of nocturnal hypoventilation, with episodes of desaturation and CO2 retention most pronounced in REM sleep, usually is revealed (Figure 63-4).

Treatment

Management of Spinal Deformity

Surgery for Scoliosis

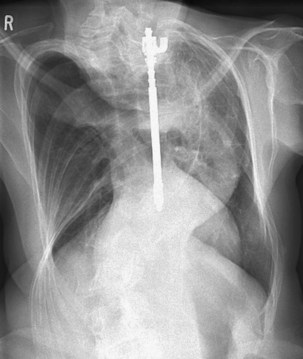

Spinal fusion followed by casting has now been superseded in many situations by rod instrumentation (Figure 63-5). The system provides distraction to the concave side of the spine and compression to the convex side, which enhances stabilization and reduces any rotational tendency. Instrumentation is used to stabilize the curve and spinal fusion to prevent growth. A posterior approach is used, but with a severe deformity or very rigid curvature, an anterior approach may be required to release the disk space. The combined anterior and posterior approach carries greater anesthetic and surgical risk. In patients with AIS, surgical complication rates are around 5% to 6%, with wound infections being more common after posterior fusion and pulmonary complications more frequent with use of an anterior approach. Weiss and colleagues have recently debated the pros and cons of surgical correction in AIS.

Controversies and Pitfalls

Clinical Signs in Scoliosis

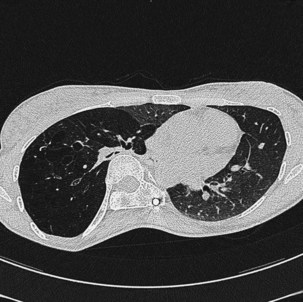

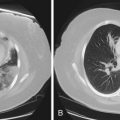

An isolated unifocal wheeze may indicate bronchial torsion or kinking, which can occur in patients with severe scoliosis and may be associated with bronchiectasis or hyperinflation in the distal lung lobe. Bronchial stenting has been successfully used in this situation. In the case shown in Figure 63-6, the right bronchus intermedius was partially obstructed by torsion and compression against the spine. The clinical consequence was development of a staphylococcal pneumonia with cystic changes affecting the right lower lobe.

Bergofsky EH. Thoracic deformities. In: Roussos C, ed. The thorax; part C: disease. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1995:1915–1949.

Branthwaite MA. Cardiorespiratory consequences of unfused idiopathic scoliosis. Br J Dis Chest. 1986;80:360–369.

Buyse B, Meersseman W, Demedts M. Treatment of chronic respiratory failure in kyphoscoliosis: oxygen or ventilation? Eur Respir J. 2003;22:525–528.

Chopra S, Adhikari K, Agarwal N, et al. Kyphoscoliosis complicating pregnancy: maternal and neonatal outcome. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:295–297.

Giampietro PF, Blank RD, Raggio CL, et al. Congenital and idiopathic scoliosis: clinical and genetic aspects. Clin Med Res. 2003;1:125–136.

Gustafson T, Franklin KA, Midgren B, et al. Survival of patients with kyphoscoliosis receiving mechanical ventilation or oxygen at home. Chest. 2006;130:1828–1833.

Lowe TG, Edgar M, Margulies JY, et al. Etiology of idiopathic scoliosis: current trends in research. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A:1157–1168.

Martinez-Llorens J, Ramirez M, Colomina MJ, et al. Muscle dysfunction and exercise limitation in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:393–400.

Orvoman E, Hiilesmaa V, Poussa M, et al. Pregnancy and delivery in patients operated by Harrington method for idiopathic scoliosis. Eur Spine J. 1997;6:304–307.

Pehrsson K, Bake B, Larsson S, Nachemson A. Lung function in adult idiopathic scoliosis: a 20 year follow up. Thorax. 1991;46:474–478.

Simonds AK. Home non-invasive ventilation in restrictive disorders and stable neuromuscular disease. In: Simonds AK, ed. Non-invasive respiratory support: a practical handbook. ed 3. London: Arnold; 2007:184–188.

Weiss HR, Bess S, Wong MS, et al Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis—to operate or not?. A debate article. Patient Saf Surg. 2008;2:25.