Chapter 16 Sciatic Nerve

The Sciatic Nerve in the Pelvis

Anatomy

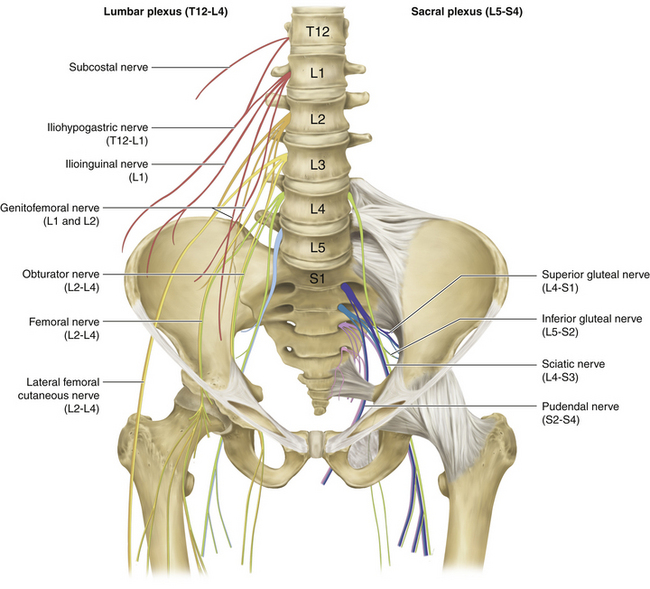

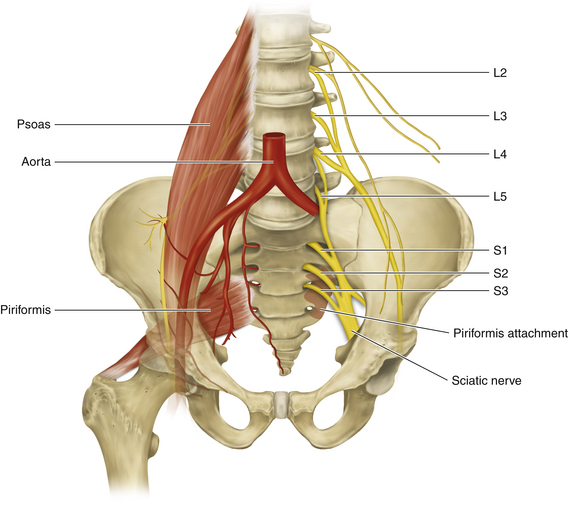

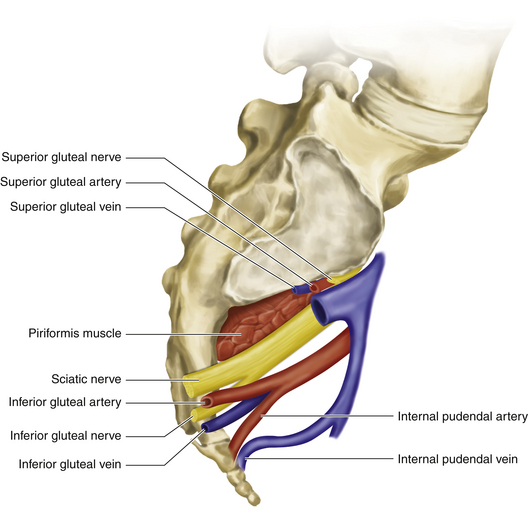

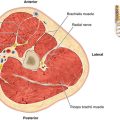

• The sciatic nerve takes its origin from the ventral divisions of the anterior primary rami of L4, L5, S1, S2, and S3. The lumbar contribution (L4 and L5) runs down anterior to the sacroiliac joint to join the sacral plexus (Figure 16-1). The sacral plexus lies behind the pelvic fascia and in front of the piriformis. Parasympathetic fibers are derived from S2, S3, and S4, close to their exit from the foramina.

• The main trunk of the sciatic nerve supplies the hamstring compartment and then separates into the tibial and common peroneal nerves, which are bound together by a common sheath of connective tissue. The sciatic nerve, formed by a confluence of the spinal nerves, escapes the pelvis by running through the greater sciatic foramen.

• The slips of origin of piriformis interdigitate with the anterior sacral foramina (Figure 16-2).The muscle exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen, with the superior gluteal nerve and vessels above it and the remaining nerves and vessels below.

• The iliac vessels lie anterior to the pelvic fascia, and the ureter descends, anterior to the bifurcating vessels, in line with the sacroiliac joint.

• The sigmoid colon has a short mesentery, and the upper rectum is covered by peritoneum on its front and sides. Further distally, the rectum is covered only in the front by the peritoneal reflection.

• A significant venous plexus drains the bowel and other pelvic viscera.

Surgical Technique

• Operations on the pelvic plexus are especially difficult, and when nerve injury or a tumor is involved, they can be very challenging. Images should be carefully studied, so that the surgeon understands the exact position of the nerve tumor relative to the surrounding bony and soft tissue anatomy.

• The surgeon should have a thorough knowledge of each spinal nerve distribution, in case consideration has to be given to sacrificing a neural element during tumor resection.

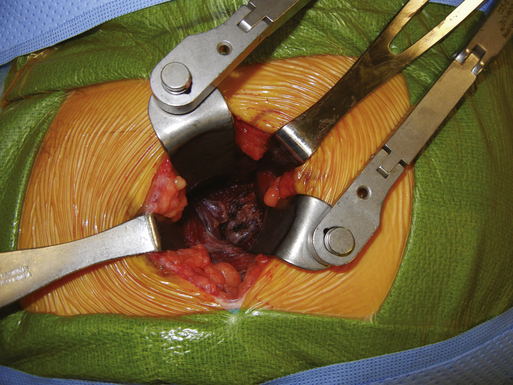

• The true pelvis, when containing a nerve tumor, presents a very cramped operating arena. The nerve surgeon needs assistance from an individual experienced and skilled in protecting the ureter, vessels, and bowel. That individual will be used to define the correct planes of dissection to avoid or control significant venous plexus bleeding.

The Sciatic Nerve in the Buttock

Anatomy

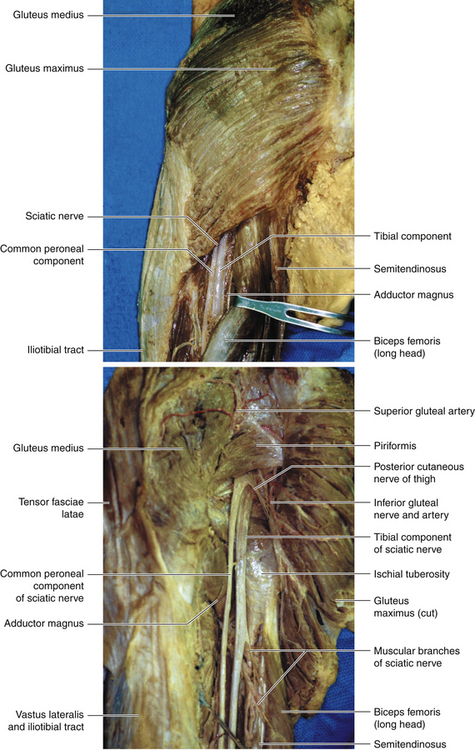

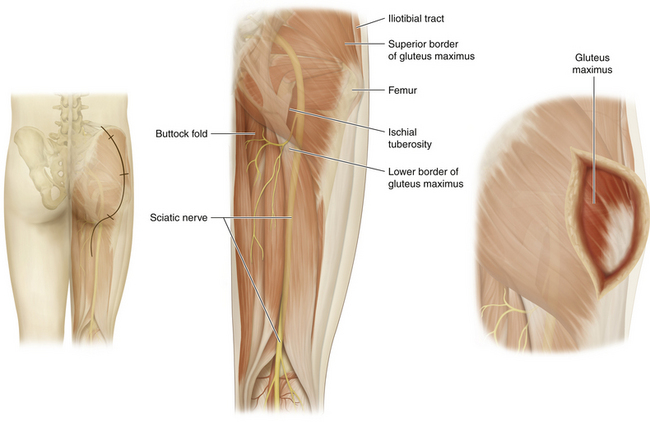

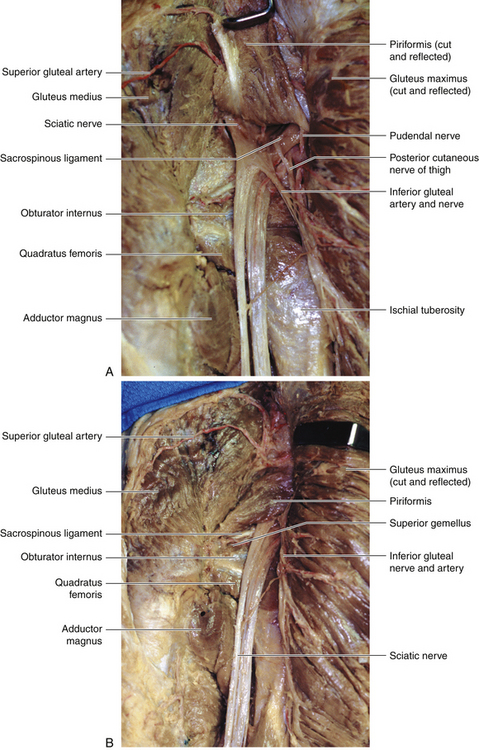

• The gluteus maximus (inferior gluteal nerve) has a dual insertion into the femur and, with the tensor fasciae latae (superior gluteal nerve), into the iliotibial tract. The superior border of the gluteus maximus is contiguous with the inferior border of the gluteus medius (superior gluteal nerve).

• The plane deep to the gluteus maximus is relatively avascular, and the entire muscle can be lifted to display the underlying anatomy.

• The piriformis originates from the front of the sacrum and is inserted into the femur. The points of insertion of both the piriformis and gluteus maximus into the femur should be clearly understood.

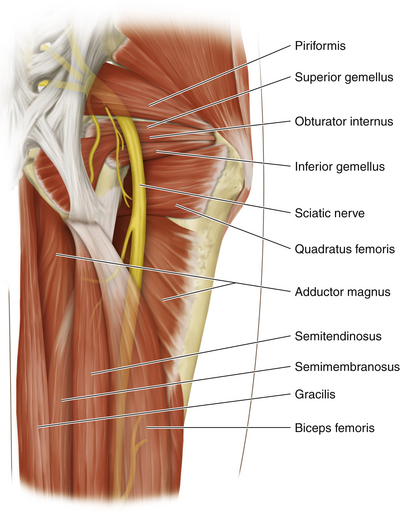

• The sciatic nerve enters the gluteal region through the greater sciatic foramen below the piriformis and comes to lie on the ischium (Figure 16-3). The nerve to quadratus femoris is deep to the sciatic nerve, and the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh lies superficial to the sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve descends between the greater trochanter and the ischial tuberosity, crossing posterior to the obturator internus and the gemelli.

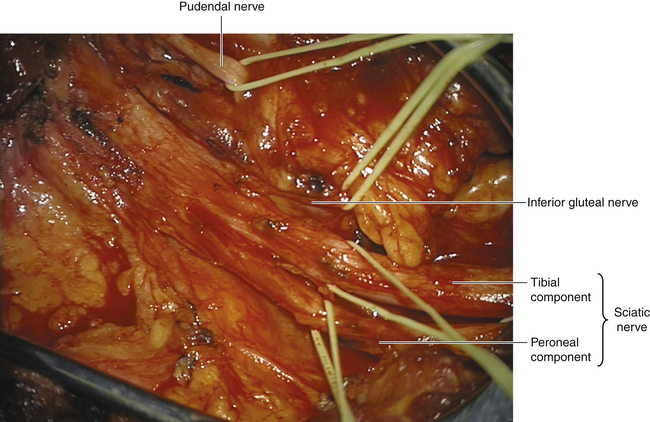

• The inferior gluteal nerve arises from L5, S1, and S2 ventral rami, and leaves the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen, below the piriformis. The inferior gluteal nerve divides into branches that sink into the deep surface of the gluteus maximus (Figure 16-4).

• The pudendal nerve is the chief nerve of the perineum and of the external genitalia. Only a small segment of this nerve is seen in the gluteal region (Figure 16-5). The pudendal nerve arises from the anterior surfaces of S2, S3, and S4 rami, passing back between the piriformis and coccygeus muscles, medial to the pudendal vessels. The pudendal nerve and its accompanying vessel exit the greater sciatic foramen to enter the pudendal canal through the lesser sciatic foramen, having passed over the ischial spine. The spine can be palpated per vaginam, and this serves as the guide for local anesthetic injection, even if the fetal head is low in the pelvis. The nerve runs forward into the ischiorectal fossa to lie in the lateral wall of the fossa.

Surgical Technique

Patient Positioning

• For a buttock-level procedure, the patient is placed prone with a folded sheet under the pelvis on the operated side.

• The knees are slightly bent and padded, and care is taken to protect the ankles and feet.

• The lower leg or legs are prepped, and are draped as well if harvesting of sural nerves for grafts is anticipated.

Incision

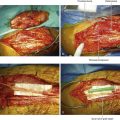

• A variety of incisions is available. In many cases the pathology is at the sciatic notch, so it is crucial that this region be clearly seen. Localized muscle-splitting incisions may be fashioned through the gluteus maximus, provided the surgeon knows with certainty that the nerve injury is localized to that position (e.g., a stab wound) (Figures 16-6 and 16-7). In complex injuries of uncertain extent (e.g., after previous hip surgery), the classic operation is employed.

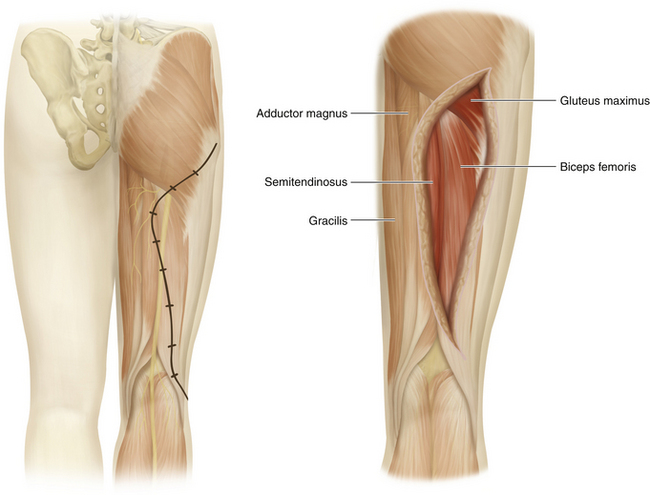

• The preferred incision begins just inferior to the posterior inferior iliac spine. It lies close to the upper free border of the gluteus maximus and then turns downward over the lateral insertions of that great muscle. If the upper thigh portion of the sciatic nerve is needed to define normal nerve distal to the injury, the incision is carried into the buttock crease and then distally, between the hamstring muscles (Figure 16-8).

Procedure

• When a heavy scar from injury involves a large portion of the buttocks, it may be necessary to begin exposure by identifying the sciatic nerve at thigh level and tracing it proximally.

• The gluteus maximus inserts laterally into both the femur and the iliotibial tract. The upper end of the iliotibial tract is attached to the iliac crest and receives muscle fibers from the tensor fasciae latae anteriorly, in addition to the posterior gluteus maximus fibers.

• The free inferior border of the gluteus maximus does not usually coincide with the buttock fold. The free upper border of the gluteus maximus is contiguous with the gluteus medius, which is not disturbed in sciatic nerve surgery.

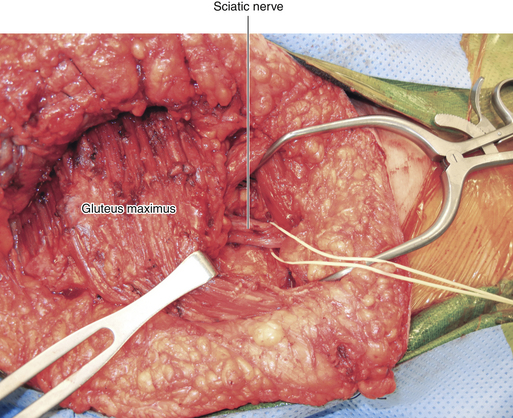

• When approached from behind, the sciatic nerve can be found after palpating the ischial tuberosity (the point of origin of the hamstring muscles) and the greater trochanter of the femur and then separating the hamstrings just below the inferior border of the gluteus maximus. A finger hooks under the nerve, which is then encircled by a Penrose drain.

• A finger is then inserted under the inferior border of the gluteus maximus, close to the femur, and the muscle is detached from both the femur and the iliotibial tract from below, working upward. A half inch of tendinous cuff is left on the femoral side, for future approximation of the gluteus maximus. The upper and lower extremities of the tendinous division are marked with heavy sutures on both sides, to facilitate accurate reconstruction at the conclusion of nerve surgery.

• The upper border of the gluteus maximus is cleared to the iliac crest.

• The posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh should be guarded and displaced medially during exposure of the sciatic nerve just inferior to the free edge of the gluteus maximus.

• In the classic posterior approach, it is important to free the upper border of the gluteus maximus right up to the iliac crest before the gluteal lid is lifted, or the surgeon will constantly be hampered at the very point of likely pathology: the greater sciatic notch.

• The gluteus maximus is then lifted by its free lateral border, and the avascular plane deep to it is gently established as the great muscle is rolled back in a medial direction.

• When the gluteal lid is hinged back, the inferior gluteal nerve and artery are pulled medially along with the gluteus maximus. Care must be given to the gluteal arteries, lest they tear (see Figure 16-4). An exsanguinating intrapelvic hemorrhage from the retracted proximal stump, necessitating emergency laparotomy and occlusion of the internal iliac artery branches, may otherwise occur.

• The use of large rakes, held by an assistant opposite the surgeon, is necessary.

• Dissection is then carried out in the relatively avascular plane deep to the gluteus maximus to expose the sciatic nerve, usually initially at a midbuttock level.

• As much vasculature as possible connected with the nerve and its major neural branches is preserved and mobilized, as is the sciatic nerve itself. The sciatic nerve is encircled with a Penrose drain, and gentle elevation and alternate lateral or medial displacement of the nerve help move the dissection farther proximally (Figure 16-9).

Anatomical Relationships at the Sciatic Notch

• In the majority of cases, the sciatic nerve exits the pelvis below the piriformis (Figure 16-10). Sometimes the piriformis lies either partially or wholly between the two divisions of the nerve, thus splitting the nerve in two over a short distance.

• The inferior gluteal nerve may also pierce the piriformis rather than appear inferior to that muscle. The surgeon should be aware of these well-described variations to avoid confusion when confronted with this particular anatomy.

• It is possible to dissect off some of the origin of the gluteus from the superior portion of the bony notch and to remove a portion of the overlying bone with an electric drill to gain access to viable proximal nerve.

• This provides some exposure of the sciatic nerve in the pelvis. This segment of the nerve is very difficult to expose by an intrapelvic approach, even under optimal conditions. It is impossible to expose the spinal nerves from a buttock-level approach.

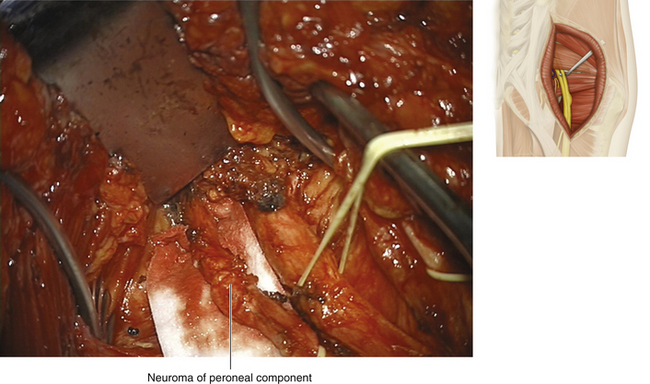

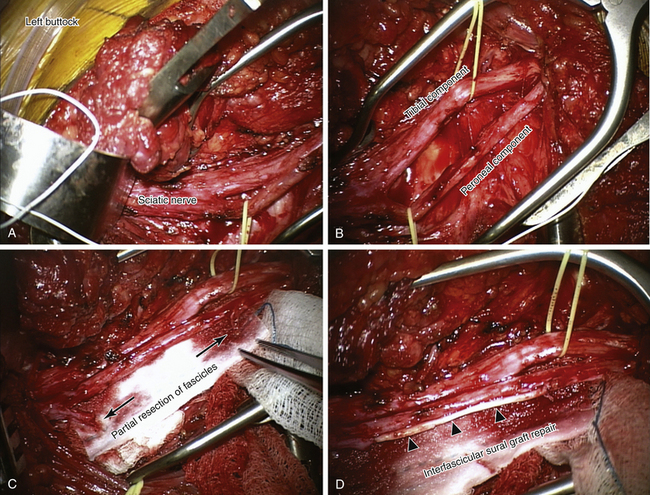

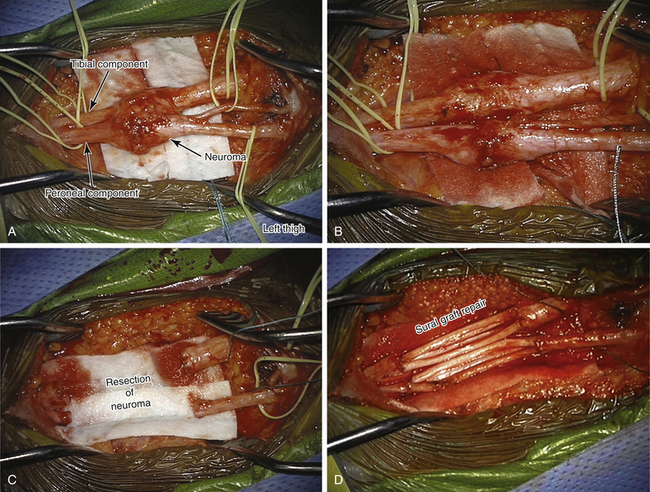

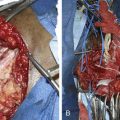

• If a lesion in continuity is able to conduct a nerve action potential (NAP), the buttock-level nerve should be split into its two divisions and each one evaluated electrically before undergoing either neurolysis or repair (Figure 16-11).

• Sometimes the site of the divisional septum in the sciatic nerve is palpable, even if it is not seen. Often the divisions are already separate and loosely apposed by thin tissue.

• Closure is by heavy suture, to sew the edge of the buttock muscle and fascia back to the tendinous cuff that was left laterally.

The Sciatic Nerve at the Thigh Level

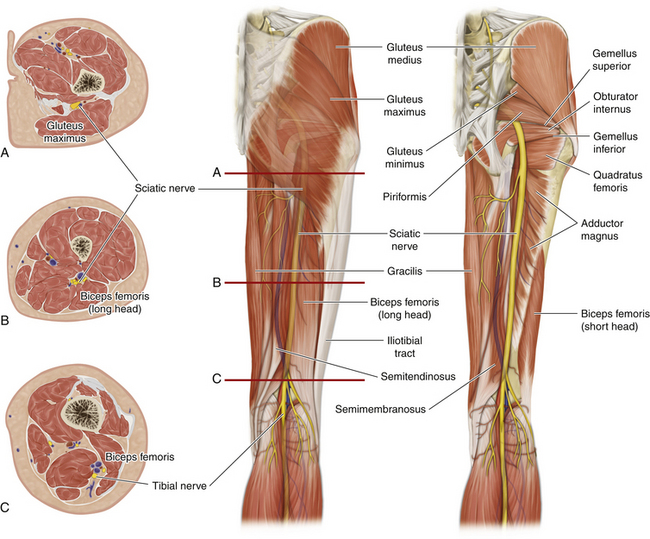

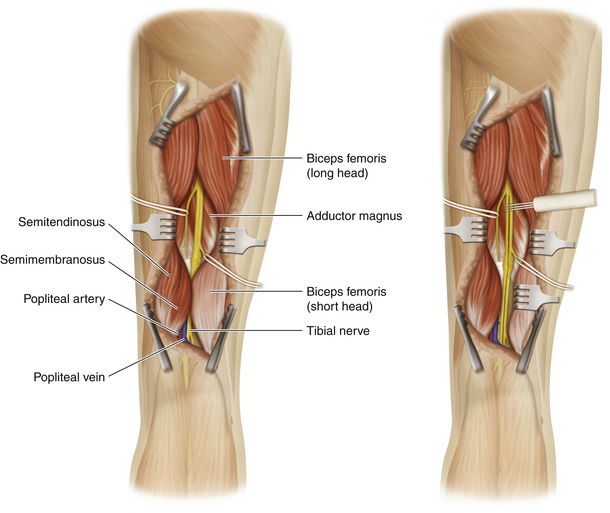

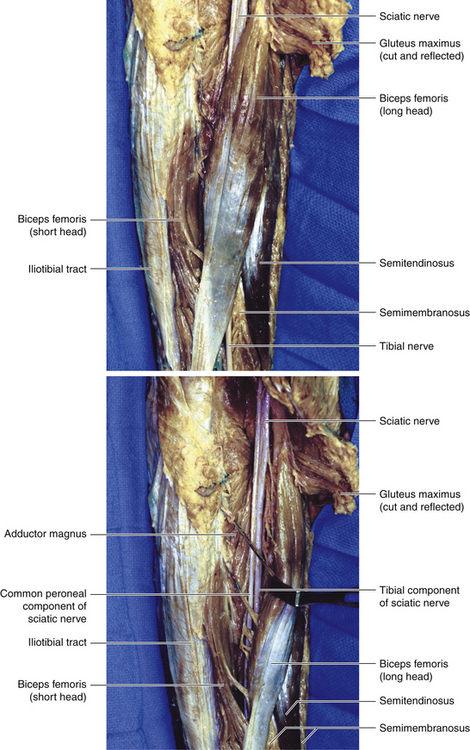

• The sciatic nerve corresponds to a line drawn from the midpoint between the ischial tuberosity and the greater trochanter to the apex of the popliteal fossa. The ischial tuberosity is easily palpated with the patient in the prone position. It is the site of origin of the semimembranosus, the semitendinosus, the hamstring component of the adductor magnus, and the long head of the biceps femoris (Figure 16-12).

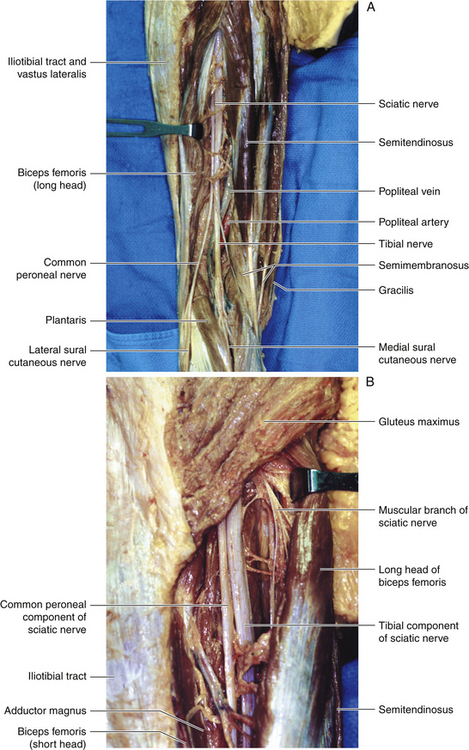

• When viewed from behind, the sciatic nerve runs down the thigh from beneath the inferior border of the gluteus maximus, between the hamstring muscles, to the popliteal fossa behind the knee joint (Figure 16-13). The sciatic nerve rests on the adductor magnus, lateral to the semimembranosus and semitendinosus. The lateral border of the proximal semimembranosus is characteristically tendinous in nature in the proximal thigh. The long head of the biceps originates medial to the sciatic nerve and is inserted laterally in the leg. This muscle, therefore, crosses the sciatic nerve superficially when viewed by the surgeon.

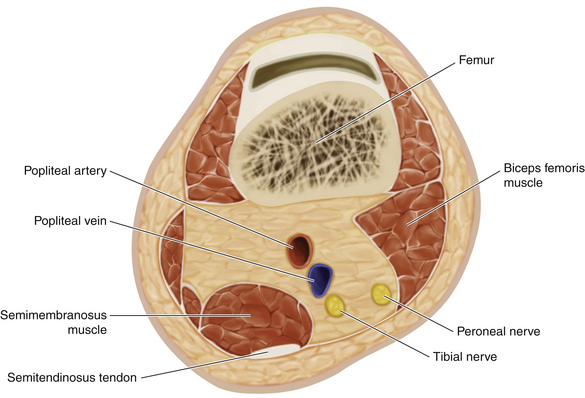

• The major arterial supply of the leg passes through the hiatus in the adductor magnus, so that the vessels lie between the nerves and the knee joint when seen through the posterior approach (Figure 16-14).

• Throughout its course the sciatic nerve is seen to consist of its two components, which are stuck together. At the distal end the point of divergence of the tibial and peroneal nerves is variable.

• The head of the fibula is easily palpable. Both the long and short heads of the biceps insert at this point.

• The common peroneal component supplies the short head of the biceps femoris. The long head of the biceps femoris receives supply from the tibial component.

• The common peroneal nerve is the smaller terminal branch of the sciatic nerve and is approximately half the size of the tibial component. It is derived from the fourth and fifth lumbar rami and the first and second sacral rami.

• The tibial component distributes muscular innervation to the semitendinosus, the semimembranosus, the long head of the biceps femoris, and the ischial head of the adductor magnus.

Surgical Technique

Incision

Procedure

• The sciatic nerve is found by separating the biceps from the semitendinosus. When the surgeon’s index finger is placed in the correct plane, the pulp of the distal phalanx immediately hooks under the sciatic nerve (Figures 16-16 and 16-17).

• It is not uncommon for a novice surgeon to gain the interval between the semitendinosus and adductor magnus (too far medial) and have difficulty finding the sciatic nerve. In complex injuries in the proximal thigh, the tendinous semimembranosus is a welcome guide to the nerve.

• The three hamstring muscles arising from the ischial tuberosity are all supplied by the tibial component of the sciatic nerve (L5 to S2). These branches may come off from the proximal sciatic nerve. Care must be taken not to injure these branches when the proximal sciatic nerve is being mobilized posterior to the hip joint and in the proximal thigh.

• At the inferior aspect of the adductor magnus, the popliteal artery gains the popliteal fossa, and the artery and its branches are closely associated with the division of the sciatic nerve. When operating from behind, the sciatic nerve is therefore superficial to the popliteal artery, vein, and branches (see Figure 16-14). If previous vascular surgery has been undertaken, the surgeon must be absolutely certain of the anatomical position of the repaired vessels.

• The posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh should be observed and guarded in proximal thigh dissections.

• The long head of the biceps angles across the upper or proximal thigh. It should be circumferentially cleared so that the muscle can be freely retracted medially and laterally. It can be encircled by one or two Penrose drains and retracted for exposure of the more proximal thigh-level sciatic nerve. There is no need to divide this muscle (Figure 16-18).

• As the biceps femoris approaches the knee joint, it forms a tendinous border that an inexperienced surgeon may mistake for the peroneal nerve. The biceps tendon is inserted into the head of the fibula, and the lateral popliteal or peroneal nerve is destined for the neck of the fibula.

• The blood supply of the sciatic nerve is from the inferior gluteal artery and pudendal artery proximally and, in its course through the thigh, from the segmental arteries. These segmental arteries should be respected, as much as is possible, in dissecting the nerve proximal and distal to the lesion.

• Basic to the approach to a sciatic lesion in continuity is to split the nerve both proximal and distal to the lesion. This permits independent, direct electrical assessment and, if necessary, separate repair of the division or divisions (Figure 16-19).

• Each division is stimulated, and an attempt is made to record a NAP through and distal to the lesion.

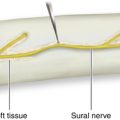

• Most of the time, sciatic repair requires the use of grafts, usually sural. Of course, if an end-to-end repair can be gained with minimal tension, this is the technique of choice.

• The leg wounds are wrapped, but are not immobilized by splints or casts. Walking begins the day after the operation.

• If possible, an exercise such as swimming should begin a month or so postoperatively.

• Weight bearing is believed to be the most effective postoperative rehabilitative step.