Scar Revision and Local Flap Refinement

Scar Revision

Wound Healing and Contributing Factors

Factors that influence scar formation and appearance after wound healing depend on the initial injury, location of the wound, and local cellular and humoral responses.1–3 Wound healing is a natural phenomenon that progresses through many states before complete healing. The stages of wound healing include initial coagulation, inflammatory phase with re-epithelialization, fibroblastic phase, and maturation phase with the deposition of collagen and glycoproteins.2 The process of healing is complete after approximately 1 year, at which time the scar will reach 80% of the original tissue tensile strength.4 Wound healing is discussed in detail in Chapter 4.

The circumstance of wounding is a factor in scar formation. Planned surgical wounds heal better than contaminated wounds.5 Skin wounds from traumatic injuries or disease usually heal with more scarring. In traumatic and surgically created wounds, greater tissue loss is associated with greater scarring. When lacerations or skin avulsions are ragged but parallel to relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs), the irregular borders can be excised and the wound closed in a straight line. However, if the wound is perpendicular to RSTLs, it may be prudent to close the wound while preserving the ragged border to help create an irregular scar.6 Thermal injuries and wounds containing foreign material are likely to heal with hypertrophy.3

Optimizing a patient’s nutrition and immune system is beneficial to wound healing. Collagen synthesis requires vitamins A and C and iron. Epithelialization requires zinc. Certain chronic diseases affect wound healing. Patients requiring insulin for diabetes, steroids for collagen vascular disease, or antimetabolites for cancer have an increased risk of poor wound healing and wound infection.7 Individuals with atrophic dermatitis or psoriasis tend to have staphylococcal colonization of their skin and as a consequence have a higher risk of postoperative wound infections. Wounds created in areas previously treated with 50 Gy or greater of irradiation are more likely to heal slowly or not at all. This is due to irradiation-induced changes of the skin that include fibrosis and obliteration of the subdermal vasculature, atrophy of the skin and subcutaneous fat, and loss of cutaneous appendages.7 Nicotine can increase the risk of skin necrosis after wounding. This is due to the effects of nicotine on the vasculature of the skin, which include endothelial thickening and damage to small vessels. It is also related to the vasoconstrictive properties of nicotine.

Ideal Scar

To achieve an ideal scar when performing flap surgery, the surgeon must have a thorough understanding of skin anatomy and physiology, perform careful analysis of the defect, be knowledgeable concerning alternative reconstruction methods, employ skillful and meticulous soft tissue handling techniques, and understand the patient’s expectations. The surgeon must also be aware of the limitations of each surgical procedure. When alternatives are available, the surgeon should avoid creating long, straight, unbroken incisions that tend to make scars more visible.8,9

Timing of Scar Revision

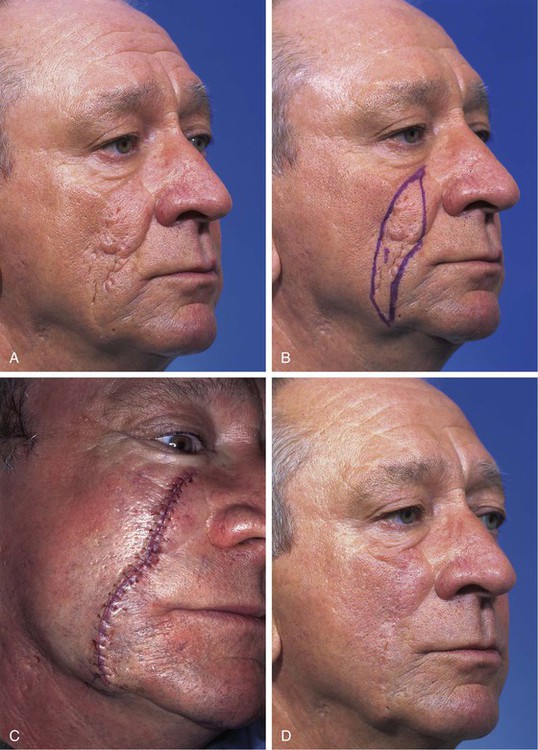

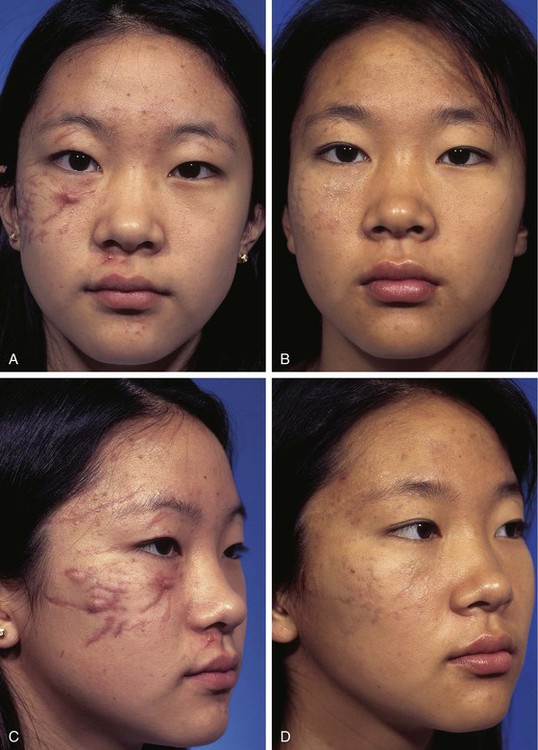

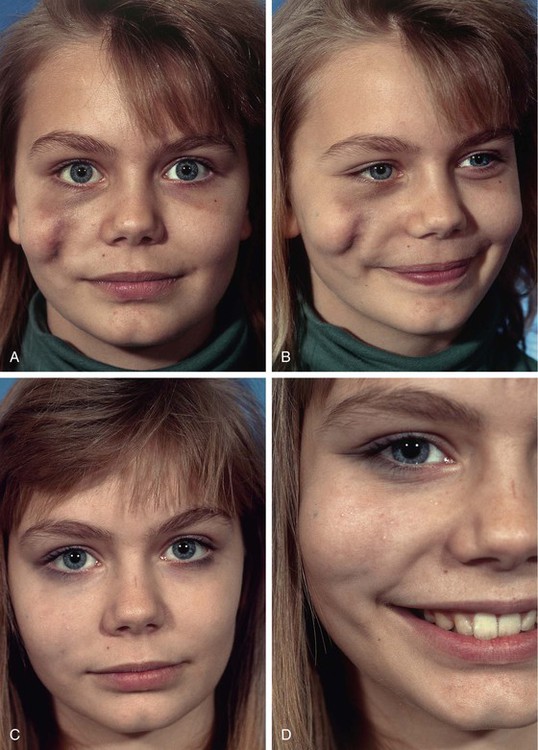

Traditional teaching dictates that scar revisions should not be performed until 6 to 12 months after the initial surgery or wounding. This is to allow scar maturation. Wounds have only 20% of their final strength by the third week of wound healing.10 Scars continue to change and to improve during the remodeling phase of wound healing. This includes collagen remodeling and collagen fiber reorientation for up to 18 months. This process can be longer in children. Young patients may have an exaggerated healing reaction with increased scar erythema and hypertrophy, so scar revisions in children should be delayed as long as feasible (Fig. 27-1). Immature scars tend to be erythematous, which will usually fade over time (Fig. 27-2). The scar’s appearance will also improve as it matures. However, early scar revision may be necessary if scars are grossly deforming, such as those that are perpendicular to RSTLs, cross or deform facial aesthetic regions or units, or have traumatically implanted foreign material. In such circumstances, it is recommended to delay scar revision for only 2 or 3 months after wounding to allow the deposition of dermal scar, which can serve as a wound base. Dermabrasion of scars may be performed 6 to 9 weeks after initial wounding. The first 2 months of wound healing manifest a high fibroblast activity and collagen remodeling; therefore, dermabrasion is more effective at this time.11,12

FIGURE 27-1 Multiple facial scars in a 13-year-old patient after an automobile accident. A-D, A few weeks after the accident and 3 years later. Scars matured and erythema regressed. Scars were treated with single intrascar injection of triamcinolone in select areas and silicone sheeting over all scars at bedtime for 1 year.

Patient Assessment

An understanding of the mechanical properties of facial skin and the principles of facial aesthetic regions and units is necessary to perform skillful scar revision surgery. Skin anatomy is discussed in depth in Chapter 1. Facial aesthetic regions and units are described in Chapter 6. A history of how the patient has healed from previous injuries is important. Patients who can bend their thumb back to the volar surface of their forearm (Fig. 27-3) or touch their tongues to their noses (Gorlin’s sign) are more flexible than the average person. These individuals possess more elastin within their dermis and are more likely to spread their scars.

FIGURE 27-3 A, Patients who can bend thumb back to volar surface of forearm possess more than average elastin in dermis. B, Same patient showing facial scars from varicella. Increased elastin in skin causes scars of all types to spread as they mature.

Patients should discontinue the use of tobacco products, nonsteroidal medications, and vitamin E before scar revision. Scar revision should not be performed in an area of active infection. Active acne should be controlled with antibiotics, topical retinoic acid, and keratolytics.7 If the patient has been taking isotretinoin (Accutane) within 18 months, dermabrasion or laser resurfacing should be postponed. Isotretinoin reduces the cellular activity of cutaneous adnexal appendages that is necessary for re-epithelialization of superficial surface wounds. Before dermabrasion or laser resurfacing, the skin may be conditioned by treatment with a tretinoin. Tretinoin has been shown to inhibit dermal collagenase, preventing breakdown of collagen. Patients should be instructed to avoid excessive sunlight exposure to a scar before and for 3 months after revision surgery.

Techniques

Scar Excision

Excisional techniques are designed to reduce wound closure tension, to change the shape of a scar, to correct uneven tissue apposition, or to fill in contour depressions. The most common excisional technique is the elliptical excision, which is used for scars that are elevated or depressed in relationship to the level of the adjacent skin. Elliptical excision is also useful for treatment of malaligned or wide scars and those that can be repositioned into an aesthetic boundary. Elliptical excision is often reserved for scars that are parallel to RSTLs or in favorable areas of the face and less than 2 cm in length. Elliptical excision is particularly useful for individual ice pick acne or pox scars or short, straight, wide, depressed, or raised scars. Fusiform incisions are made parallel to RSTLs or in aesthetic boundaries. The ellipse is designed with angles of 30° or less at each end to prevent skin redundancy. To shorten the elliptical excision, an M-plasty may be performed. Excisions that are longer than 1 cm may be designed sinusoidally and parallel to contour lines or RSTLs. Compared with a standard elliptical excision, a lazy S–shaped excision may close easier and avoid bunching at the ends of the wound with less midpoint wound closure tension.13 The length-to-width ratio of elliptical excisions should be 3 : 1 to allow wound closure without standing cutaneous deformities. If standing cutaneous deformities form, they can often be corrected by sewing out the extra length. When the two borders of an incision are unequal in length, a standing cutaneous deformity may occur along the border of the wound with the longest length. An equalizing Burow triangle can be excised to shorten the long border. This consists of making an incision perpendicular to the long side of the wound and removing a triangle of skin. In performing an elliptically shaped scar excision, it is helpful to leave the deeper dermal scar in situ to augment the depth of the wound. Most scars are excised just outside of the scar margins; however, keloids and hypertrophic scars heal with less hypertrophy if they are excised slightly inside the margin of the scar.14,15

Scar excisions in the form of skin punch excisions to treat ice pick–type acne scars may be beneficial. The depressed scar is punched out with a skin punch and discarded. The edges of the wound are approximated with eversion. This works well if the adjacent skin is normal. Punch grafts from the postauricular skin can be placed into the hole created by excised ice pick scars. Punch excisions and grafts are usually followed by dermabrasion within 6 weeks to achieve optimal results.16 Punch incision can also be performed and the scar plug elevated and sutured to the adjacent skin.

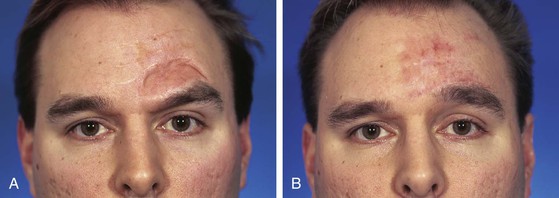

Partial or multiple serial excisions of scars may be used when the elasticity of the scar and surrounding tissue prohibits one-stage excision. Stress-relaxation causes tissue to stretch over time, which facilitates re-excision of scars.17 Serial excision is a particularly useful technique for removal of skin grafts or pigmented lesions (Fig. 27-4). It may also be an effective method for excision of broad scars and burn scars or where severe disfigurement would occur if the area were excised in one stage. Tissue expansion can accomplish the same goal as serial excisions of scars but in two or more stages. Tissue expansion uses the advantage of the stress-strain curve beyond the elastic limit of skin.18 Adjacent tissue usually provides the best skin color and textural match for repair of wounds. Thus, tissue expansion or serial excision provides a method of transferring like tissue into an area deficient of skin where a single surgical stage does not provide a means to accomplish this.18

FIGURE 27-4 A, Full-thickness skin graft of left side of forehead. B, One year after serial excision of graft.

Proper tissue handling is important for successful scar excision techniques. Undermining in the subcutaneous tissue plane at least 1 cm beyond the borders of the scar excision is necessary to reduce wound closure tension.17 Dermal approximation is recommended to reduce tension and to eliminate dead space. Accurate alignment of muscles is necessary for proper restoration of function. Absorbable sutures are used for dermal apposition with attention toward precise eversion of wound edges to prevent discrepancies in the level of the epidermis. Eversion of the skin edges of a wound can be accomplished with deep subcutaneous sutures, epidermal vertical mattress sutures, or simple cutaneous sutures placed perpendicular to the skin surface. Unequal depths of the bites of the dermis on either side of the wound may be necessary to create a level everted wound edge. There is much controversy concerning the preferred method and materials used for closure of wounds. Issues include the use of absorbable or nonabsorbable cutaneous sutures and whether to repair a skin incision with simple running or mattress sutures. Karounis et al19 and Singer et al20 studied the issue of absorbable versus nonabsorbable cutaneous sutures and found that the repair of traumatic lacerations in children with absorbable sutures appeared to be as acceptable as that with nonabsorbable sutures. The long-term aesthetic results were deemed to be similar.19,20 An in-depth discussion of wound closure techniques is presented in Chapter 4.

Scar Irregularization

Z-Plasty

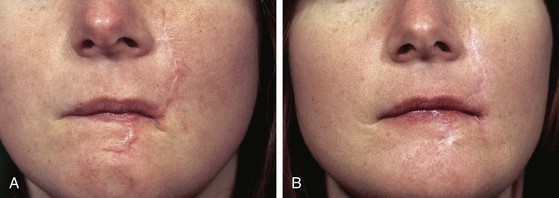

Z-plasty is a form of scar irregularization. It can be used to interrupt scar linearity, to elongate contracted scars, to efface webs or clefts, and to change the orientation of scars so that the majority of the length of a scar is aligned with RSTLs.9,17 Z-plasty can also be used to correct distorted anatomic facial landmarks caused by scars (Figs. 27-5 and 27-6). An example of this is use of a Z-plasty to lengthen a scar causing lower eyelid retraction.21 Z-plasty can realign a scar that crosses the alar-facial sulcus or melolabial crease. Z-plasty is an effective method of reducing trap-door deformity.

FIGURE 27-5 A, Hypertrophic scars of cheek and upper and lower lips after a dog bite. B, Improvement of scars after staged Z-plasty procedures (three stages) and dermabrasion.

FIGURE 27-6 A, Scarring of upper lip with distortion of vermilion border. B, After multiple Z-plasties and two dermabrasions of scars.

In designing a Z-plasty, all limbs and angles of each triangular flap are equal to each other. The angles of the tip of the flaps may vary from 30° to 60°. The degree of release of contracted scars by Z-plasty is related to the size and angulation of the triangular flaps of the Z-plasty. Flaps of 60°, 45°, and 30° will have the effect of releasing a contracted scar by approximately 75%, 50%, and 25% and changing the orientation of the scar 90°, 60°, and 45°, respectively.2 The final position of the new central limb of the Z can be predicted by envisioning an imaginary line that connects the two free ends of the original Z.

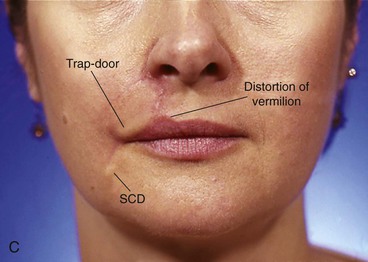

Z-plasty is a powerful and effective method of correcting distortion of the vermilion or realigning irregularities of the vermilion. Figure 27-7 shows distortion of the vermilion after an A-T wound closure of a 1.5-cm skin and vermilion defect of the upper lip. The deformity was first corrected by employing a double Z-plasty to lower the level of the vermilion border in the midline (Fig. 27-7E). A second surgical stage was performed to reconstruct a Cupid’s bow. This was accomplished by using a V-Y island advancement flap based on a subdermal orbicularis muscle pedicle. A small ellipse of vermilion was excised to create a midline tissue void that allowed inferior advancement of the island flap to create the resemblance of a Cupid’s bow (Fig. 27-8). This is an effective method of restoring this important landmark of the upper lip. Another example of this technique is discussed in Chapter 9.

FIGURE 27-7 A, A 1.5 × 1.5-cm defect of skin and vermilion repaired with A-T wound closure (see Chapter 9). B, Scar contraction caused distortion of vermilion. C, D, Double Z-plasty used to correct distortion. E, Postoperative result at 3 months.

FIGURE 27-8 A, Same patient shown in Figure 27-7. V-Y island advancement flap based on orbicularis oris muscle pedicle designed to restore Cupid’s bow. Flap advanced inferiorly after resection of small ellipse of vermilion. B, Flap in place. C, Postoperative result at 1.5 years. Resemblance of Cupid’s bow restored to vermilion border.

Figure 22-9 shows distortion of the vermilion border of the upper lip after reconstruction of a 2 × 2-cm skin defect with a rotation lip flap. The distortion resulted from contraction of the vertical scar along the length of the medial border of the flap. In addition to causing distortion of the vermilion border, the scar was excessively wide and exhibited a slight depressed contour. To correct the vermilion deformity and to improve the contour of the scar, a Z-plasty was performed. This was successful in restoring a natural border to the vermilion and in correcting the depressed scar.

FIGURE 27-9 A, A 2 × 2-cm skin defect of upper lip. Rotation flap designed for repair. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformity (horizontal lines) marked for excision. Z-plasty marked at pivotal point of flap. B, Flap in place. C, Healing of flap resulted in distortion of vermilion border. D, E, Z-plasty performed to correct distorted vermilion border. F, Six months after Z-plasty.

Notching of the nostril margin can result from lacerations of the nostril or after reconstruction of the alar or nasal facet with a local cutaneous flap or skin graft. If the notching is not severe, it can frequently be corrected with Z-plasty (Fig. 27-10). The linear axis of the notch is incorporated into the central limb of the Z-plasty. Triangular flaps with angles of 45° to 60° are marked on either end of the central limb to complete the Z-plasty design. Transposing the flaps releases the contracture of the scar causing the notching. On occasion, insertion of a small cartilage graft beneath the flaps of the Z-plasty may be beneficial in reinforcing the scar lengthening achieved with the Z-plasty.

FIGURE 27-10 A, A 1.5 × 1.5-cm skin and soft tissue defect of ala. B, Four months after reconstruction. Ala repaired with auricular cartilage graft for structural support and interpolated melolabial flap for external cover (see Chapter 18). Notching of nostril margin has occurred. C, D, Z-plasty performed to correct deformity. E, Four months after Z-plasty.

A common use of Z-plasty is for release of scar contractures. Scar contractures can result from any cutaneous surgery. Severe contractures may occur in scars resulting from burns or deep skin injury from the use of laser or chemical peels. Z-plasty is frequently employed in the treatment of burn scars of the neck to release contractures that impair movement of the head and neck. Frequently, multiple Z-plasties are required (Fig. 27-11). Chapter 14 is devoted solely to the subject of Z-plasty.

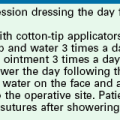

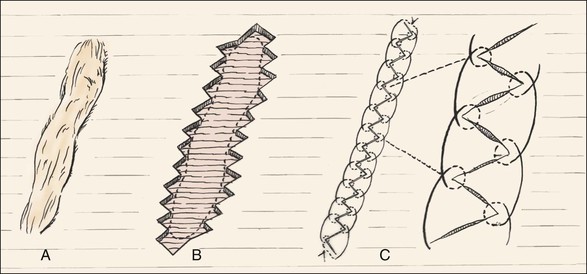

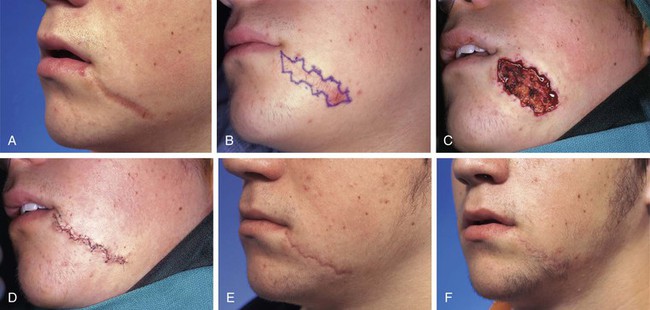

W-Plasty

Like Z-plasty, W-plasty is another method of converting a scar with a regular configuration into one with an irregular pattern. A W-plasty consists of uniform interposed triangular advancement flaps (Fig. 27-12).17,22 It creates a recurring irregularly patterned scar that is less likely to be noticed by an observer’s eye. W-plasty creates a scar that avoids sharp demarcation between scar and adjacent skin by interdigitating small triangles of normal unscarred skin, which has the effect of camouflaging the scar. W-plasty may also be helpful in aligning scars to more nearly approximate the direction of RSTLs of the face.23 It is indicated for scars of the forehead, eyebrow, temple, nose, cheek, and chin that are oriented 35° or more from RSTLs (Fig. 27-13).24 W-plasty is frequently effective in improving the appearance of scars over a convex facial contour. Examples are scars located along the mandibular border, the anterior surface of the ear, and the central forehead.7,17,22

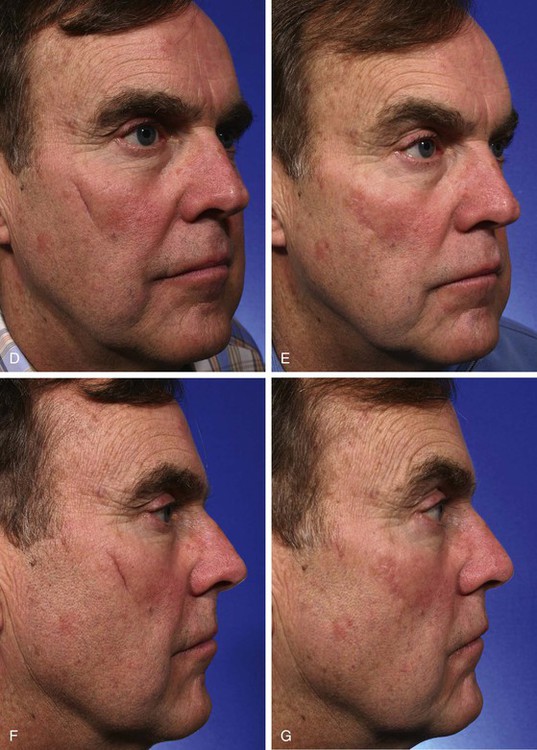

FIGURE 27-12 A, Scar perpendicular to RSTLs. B, W-plasty performed by designing repeating triangular flaps roughly parallel to RSTLs on either side of scar. Scar excised and flaps interdigitated. C, Wound closure with interrupted buried dermal sutures and running locked 6-0 rapidly absorbing gut suture.

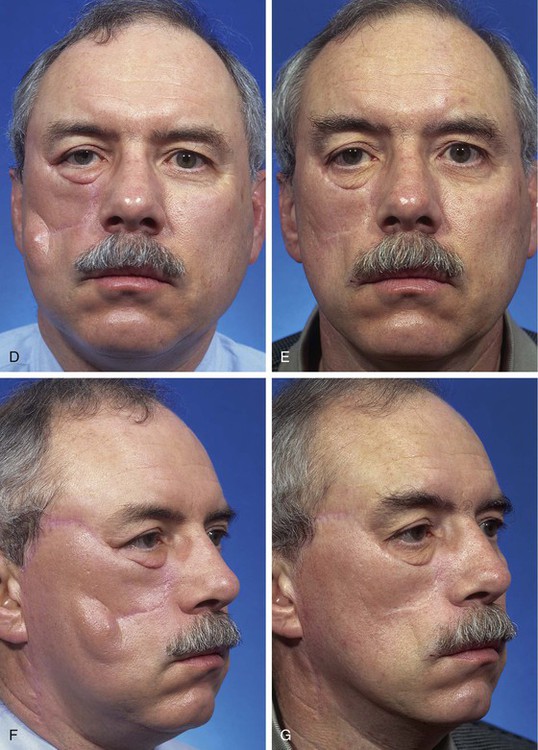

FIGURE 27-13 A, W-plasty designed to revise cheek scar. B, C, Scar excised and W-plasty completed. D-G, Preoperative and 2-month postoperative views.

In performing a W-plasty, the scar should be outlined and RSTLs should be marked where they cross the scar. The orientation of the triangular flaps of the W-plasty is parallel to the RSTLs or slanted in the direction of the RSTLs.17 A series of Ws are drawn so that the apices of the triangles are 5 to 7 mm peripheral to the scar (Fig. 27-14); 3 mm or less tends to be too small to irregularize the scar sufficiently to prevent it from appearing as a straight line, and limbs of more than 7 mm are sufficiently long that the limbs of the flaps create a scar that is individually visible. A mirror image of the first side is drawn on the opposite side of a scar so that the tips of the triangular flaps will interdigitate when the skin is advanced perpendicular to the direction of the scar. Angles of the W-plasty should be designed to be at least 60° to allow adequate tissue interposition, optimal vascularity with minimal tip of flap edema, and interposition of tissue that will resist scar contracture.3,7 A M-plasty can be used at the end of the scar to prevent extension of the incision. Incisions should be made with a No. 11 scalpel blade. Mature subdermal scar tissue is left in situ to help resist contracture and depression of the scar during healing. Wide undermining of the borders of the incisions is performed. The wound is approximated in layers. The cutaneous suture may be a running locking or interrupted suture of nylon or 6-0 fast absorbing gut. Exact alignment of the epithelial surface is critical. The wound is reinforced with paper tape for 1 week. The greatest disadvantage of W-plasty is that it creates a scar that is predictably irregular, so when a long scar is revised, it may result in a new scar that is still readily detected by an observer. Thus, for very long scars (more than 4 cm), a geometric broken-line closure is recommended.

FIGURE 27-14 A, Unsightly scar from rotation flap. Superior portion of scar is perpendicular to RSTLs. B, Superior portion of flap contoured concomitant with W-plasty scar revision. Persistent standing cutaneous deformity excised inferiorly. C, D, Scar excised and W-plasty completed. E, Postoperative result at 1 year.

Geometric Broken Line

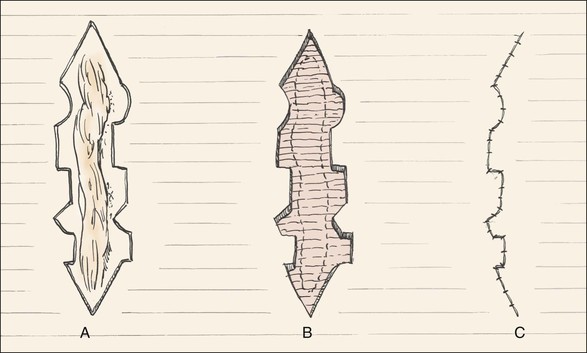

The greatest disadvantage of W-plasty scar revision is that the procedure creates a predictably irregular scar. Thus, long W-plasties may cause a scar to be more detectable than if a geometric broken-line scar revision is performed. A geometric broken-line scar revision consists of a series of random, irregular geometric shapes incised along one border of the scar with the mirror image of this pattern incised on the opposite border (Fig. 27-15). The randomness of the design causes the scar to be more difficult for the observer’s eye to follow, thus having the effect of scar camouflage. The geometric broken line is most useful for treatment of scars that are long and linear and cross RSTLs (Fig. 27-16). Similar to W-plasty, each geometrically shaped component of a geometric broken-line scar revision should measure 3 to 7 mm in length.22 Much of the scar created by the geometric broken-line technique will not parallel RSTLs. Rectangle-shaped components should be interspersed with other angular shapes to prevent circular scar contraction. To reduce trap-door deformity, the use of curved components should be limited (Fig. 27-17). Similar to W-plasty, the superficial portion of the scar is excised, leaving the deep dermal and subdermal scar in situ. The surrounding borders of the excised scar are widely undermined, and the geometrically shaped skin edges of the wound are carefully opposed so that the corresponding geometric shapes fit precisely together. A two-layered wound closure is always performed.

FIGURE 27-15 Geometric broken-line scar revision. A, Random geometric figures designed on either side of scar. B, Scar excised, leaving mirror-image wound edges. C, Wound edges advanced and approximated with running locking 6-0 rapidly absorbing gut suture.

FIGURE 27-16 A, Wide unsightly scar not parallel to RSTLs. B, Geometric scar revision designed. Geometric shapes mirror each other on either side of scar. C, Note how wound spreads when contracted scar is excised. D, Wound approximated. E, Postoperative result at 4 months immediately before dermabrasion. F, Postoperative result at 10 months.

Wound Care

Proper wound care after scar irregularization is important. Re-epithelialization of the wound begins 2 days after injury.6 The wound is cleaned with water or hydrogen peroxide twice daily, and antibiotic ointment is applied for 48 hours. The wound is kept moist with occlusive ointment until the sutures are removed. The ointment helps prevent debris and exudates from accumulating between wound edges, which can separate and cause widening of the wound edges. Cutaneous sutures are removed in 5 days to prevent epithelial tracking and to avoid punctate scars. After the removal of sutures, Steri-Strips are applied along the scar. Epithelial abrasion of the scar is usually performed 6 to 8 weeks after scar irregularization. Protection from sunlight is recommended to decrease postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

V-Y and Y-V Advancement Flaps

V-Y advancement is useful in situations in which a structure or region requires lengthening or release from a contracted state. The technique is particularly effective in lengthening the columella during the repair of cleft lip nasal deformities in which a portion or all of the columella is underdeveloped. A V-shaped advancement flap is elevated, recruiting skin from the midportion of the lip between the philtral ridges. The length of the columella is augmented by advancement of the flap upward into the base of the columella. The secondary donor defect is approximated by advancement of the remaining lip skin together in the midline. V-Y advancement is helpful in releasing contracted scars that are distorting adjacent structures, such as the eyelid or vermilion.25 An example is the correction of a contracted scar causing elevation of the vermilion border. The segment of distorted vermilion is incorporated into the V-shaped flap and the flap is advanced toward the lip to restore the natural topography of the vermilion-cutaneous junction. The skin of the borders of the secondary defect is then advanced toward each other and sutured. This suture line becomes the vertical component of the Y configuration. The V-Y island advancement flap is also useful in restoring Cupid’s bow after repair of midline upper lip defects in which Cupid’s bow has been destroyed (Fig. 27-18; see also Fig. 27-7). This is accomplished by a midline upper lip island flap based on its subdermal orbicularis muscle pedicle. A small ellipse of vermilion is excised to create a tissue void in the area of the missing Cupid’s bow. This excision should be slightly larger than ideal to correct for scar contraction. The island flap is then advanced into the defect created by the vermilion excision. As with all V-Y island advancement flaps, the donor defect is closed by advancing adjacent skin.

FIGURE 27-18 A, A 2.5 × 1.5-cm skin defect of filtrum and vermilion. B, C, Defect converted to full thickness and closed primarily. D, Postoperative result at 1 year. Note absence of Cupid’s bow. E-H, Construction of Cupid’s bow with V-Y island advancement flap. I, Six months after construction of Cupid’s bow. Scar dermabraded 2 months after revision surgery.

The Y-V advancement flap has a similar principle to the V-Y flap except that the V-shaped flap is stretched or pulled toward a linear incision made at the apex of the triangle-shaped flap. The borders of this incision are allowed to spread apart, creating a tissue void. The flap is advanced into the void and sutured in place. The wound closure suture line assumes a V configuration. The maximal wound closure tension is at the apex of the flap. The Y-V advancement flap has fewer applications than the V-Y flap but may be used on some occasions to relocate a distorted facial structure in a more natural position. An example would be in correcting the position of an oral commissure that has been displaced medially by the scar. The commissure is incorporated into the triangular flap, and a horizontal incision is made lateral to the commissure. The flap consisting of the commissure is then advanced laterally into the tissue void created by the horizontal incision, restoring a more natural position to the commissure.

Dermabrasion

Dermabrasion can improve scar color and texture, which may help camouflage the scar. Dermabrasion causes a superficial injury to the papillary dermis that heals by re-epithelialization from adnexal structures in the reticular dermis. This healing process results in a smoother surface. This phenomenon occurs because of the deposition of new collagen within the dermis of the treated area. Superficial collagen bundles develop a more organized appearance and display an increased density, bundle size, and unidirectional orientation after dermabrasion.26 Dermabrasion can improve surface irregularities and pigmentary discrepancies between flaps or grafts and adjacent skin (Figs. 27-19 and 27-20). It may be useful in improving step-off deformities of scar margins and the skin color and texture match of a flap with the adjacent facial skin. In this regard, dermabrasion is particularly helpful when a cheek flap has been used to reconstruct a defect of the upper or lower lip in older patients who have perioral rhytids. In such circumstances, the cheek flap will not display similar vertically oriented rhytids. This can result in a marked discrepancy in skin texture between flap and native lip skin (Fig. 27-21). Dermabrasion of the native lip skin will reduce the presence of the rhytids and provide an improved skin color and texture match with the flap skin.

FIGURE 27-19 A, Hyperpigmentation of full-thickness skin graft. B, Immediately after dermabrasion of skin graft to improve color match with adjacent cheek skin. C, Seven months after dermabrasion. Color match has improved.

FIGURE 27-20 A, A 4 × 2.5-cm skin and vermilion defect of upper lip. B, Defect covered with full-thickness skin graft. C, Postoperative result at 7 months. Graft has poor color and texture match with native lip skin. Vermilion absent in area of graft. D, E, Vermilion created with bipedicled mucosal advancement flap. Skin graft dermabraded. F, Five months after mucosal advancement flap and dermabrasion of graft.

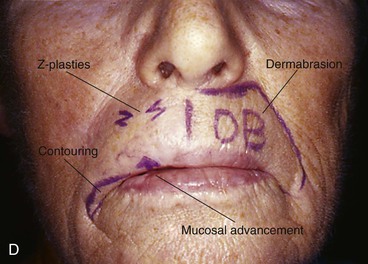

FIGURE 27-21 A, Lentigo maligna of upper lip marked for excision with vertical lines. Inferiorly based melolabial transposition flap designed to reconstruct lip after resection of melanoma. B, Tumor excised and flap transposed. C, Six months after reconstruction. Flap displays trap-door deformity and marked discrepancy between skin texture of flap and native lip skin. D, Lip marked for dermabrasion (DB), two Z-plasties, mucosal advancement flap, and flap contouring (commissure). E, Revision surgery completed. F, Seven months later. Note improved skin texture match between flap and lip.

After scar irregularization, dermabrasion is recommended 6 weeks later to optimize scar camouflage and to smooth and blend wound edges with surrounding skin. Spot dermabrasion of traumatic scars is usually beneficial and can be performed 1 to 3 months after injury. This time frame is when collagen is undergoing active remodeling. Katz27 found that scars improved most when dermabraded 8 weeks after their development, and Yarborough showed that immature scars respond better after resurfacing than mature scars do.28,29

The entire scar and adjacent skin are dermabraded to allow uniform texture and color. The depth of the dermabrasion at the periphery should be feathered to facilitate a smooth transition. If a skin graft is dermabraded, the depth of abrasion is limited over the graft because of lack of dermal appendages unless the graft was full thickness and harvested from the face. Dermabrasion is performed with an electric-powered rotary wheel at 10,000 to 15,000 rpm. Diamond fraises are available in different coarseness and shapes. Abrasion is carried to the level of the upper to mid reticular dermis along the borders of the scar and to the papillary (punctuate bleeding) dermis elsewhere. The endpoint can be determined on the basis of pinpoint bleeding, which indicates the invasion of the capillary plexus of the dermal papillae.30 The skin can be painted with gentian violet to provide a helpful guide to the depth of dermabrasion and to act as an antiseptic. Dermabrasion should progress until all the violet is removed, indicating that the epidermis has been completely removed. When dermabrasion is performed near mobile structures, the direction of rotation of the fraise should be oriented toward the structure to avoid tearing of tissue at the margin of the structure.

Dermabrasion wounds are covered with an occlusive dressing. The area should be cleaned with water and acetic acid (25% concentration) to soften any crusts. A petroleum ointment or hydrocolloid dressing is used after each cleaning for 5 to 7 days. Scabbing and crusting increase the risk of scarring.31 Occlusion enhances epithelialization, reduces discomfort, prevents infection, and minimizes eschar formation. This allows the wound to heal faster with a decreased risk of scarring. Re-epithelialization of the wound occurs within 7 to 10 days. Postoperative erythema lasting up to 3 months can be normal. During this interval, sunscreen protection must be used at all times to avoid hyperpigmentation.

Laser Resurfacing

Similar to dermabrasion, smoothing of scars can be accomplished by laser resurfacing. A laser is a beam of photons with a wavelength dependent on the base substance used to create the laser. The three most important lasers used for scar revision are carbon dioxide (CO2) lasers, yttrium-aluminum-garnet (YAG) lasers, and pulsed dye lasers. The CO2 and erbium:YAG lasers ablate superficial tissues by vaporization of water in skin cells.30 Pulsed dye lasers are frequently used to treat hyperemic and hypertrophic scars.32 Pulsed lasers allow the energy of the laser beam to be delivered in a narrow pulse during a short time. The short time of delivery of the energy to the skin limits the conduction of heat to adjacent tissues, which in turn limits damage to adjacent tissues.33–35 The short pulse or continuous wave CO2 laser with a flash-scanning attachment can be safely used for scar resurfacing 4 to 8 weeks after wound repair. A precise depth of injury can be achieved with laser resurfacing. For optimal results, a greater depth of laser ablation is desirable along the borders of scars and a more superficial level in the depths of scars. In general, elevated scars improve more with laser resurfacing than depressed scars do. Cotton et al36 demonstrated new collagen formation in the dermis after laser treatment, along with elastic fiber alteration in the papillary dermis.

Which is better for scar resurfacing, dermabrader or laser? Dermabrasion is more dependent on the skill and experience of the surgeon but requires less expensive equipment. There is the theoretical risk of aerosolization of skin cells and blood from dermabrasion. Lasers have selective photothermolysis that can ablate water-containing tissues, providing surgeons greater control of the depth of injury.37 The thermal damage by lasers is thought to increase collagen remodeling but causes prolonged postoperative erythema. Nehal et al38 compared halves of scars treated to the level of the superficial reticular dermis by dermabrasion or CO2 laser. Observer analysis and optical profilometry suggested improvement with both modalities without a statistically significant difference when the two modalities were compared. Both dermabrasion and laser resurfacing have their place in scar revision. Small areas are best treated with dermabrasion because of convenience and cost.

The pulsed erbium:YAG laser (2936 nm) has also been used for resurfacing of scars. It can improve atrophic and depressed facial scars, such as those resulting from acne and chickenpox.39 The laser is used in shorter pulses and ablates more superficially than the CO2 laser and is absorbed 12 to18 times more efficiently by water.40 It produces less tissue destruction for each application compared with the CO2 laser. There is minimal adjacent thermal injury because of the laser’s unique absorption characteristics in water, and thus there is a low risk of permanent melanocytic injury.41,42 The laser does not coagulate small vessels, so hemostasis may be a problem, and there is limited collagen contraction, which leads to less impressive clinical results.37 Some machines combine erbium:YAG and CO2 lasers so that they can be used in tandem, providing both ablative and coagulative properties. This combination provides greater contraction of collagen and improved hemostasis.43,44

Scars may heal with hyperpigmentation and fine telangiectasias. Hyperpigmentation and redness may fade up to 2 years after wounding. Because of persistent angiogenic stimuli or delayed capillary regression, some scars remain erythematous.45 The 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser has been helpful in improving color, texture, and pliability of certain scars.42,46 The laser beam is absorbed by hemoglobin and penetrates the epidermis without destruction.30 The laser is most effective for erythematous and hypertrophic scars. It is not as useful in darker-skinned patients because of the competitive absorption of laser energy by melanin and hemoglobin. The mechanism of action is selective photothermolysis of small cutaneous vessels, resulting in the reduction of redness of the scar.47 This laser has also been shown to improve the appearance and to reduce pruritus of keloids.45,48,49 Treatments can be repeated at 6- to 8-week intervals. Alster48 demonstrated a 57% to 83% reduction in pigmentation, vascularity, pruritus, and bulk of keloid scars treated with the 585-nm pulsed dye laser. Alster treated half of the scars with CO2 and pulsed dye lasers and the other half with CO2 laser alone. The scars treated with both lasers showed significant improvement in clinical appearance and erythema compared with the single modality–treated portion of the scars.46

New collagen deposition in the skin has been demonstrated histologically with nonablative lasers, such as the 1320-nm neodymium:YAG (Nd:YAG) laser,50 intense pulsed light source,51,52 484-nm pulsed dye laser,53 and 1540-nm erbium : glass laser.54 Nonablative lasers do not cause any detectable injury to the surface of the skin. The 1320-nm Nd:YAG and 1450-nm diode lasers create selective thermal injury in the dermis without damage to the epidermis. The laser energy generated by these devices penetrates to the papillary and midreticular dermis and is absorbed by water.55 They have been shown to improve acne scarring by enhancing dermal collagen remodeling.31 Their use requires multiple treatments before improvement can be visualized.55 Tanzi and Alster56 performed a comparison of the 1450-nm diode laser and 1320-nm Nd:YAG laser in the treatment of atrophic facial scars and found the 1450-nm diode laser to be superior even though both showed an increase in dermal collagen. Maximum results are seen 6 months after a series of treatments are performed, and only improvement in the scar’s surface texture can be expected.

The postoperative complications of laser resurfacing include pigmentary changes, scarring, acne, milia, erythema, and herpetic breakouts.30 The most common complication is the development of hyperpigmentation, particularly in patients with darker skin. Hyperpigmentation improves over time and with the use of topical hydroquinone. Sun exposure will exacerbate hyperpigmentation, so use of sunscreens is imperative. Hypopigmentation of the skin is commonly observed with deeper levels of laser resurfacing and occurs in 20% of patients treated with the CO2 laser.43 Ablative lasers tend to cause prolonged erythema, which is often treated with hydrocortisone. Milia may develop approximately a month after laser resurfacing. Herpes simplex can be reactivated in the area treated by laser resurfacing, thus the need to treat all patients prophylactically with an antiviral medication. Delayed healing may be observed in patients with autoimmune disorders, diabetes, or steroid dependency. Patients with collagen vascular diseases have an increased risk of scarring and persistent erythema. The skin covering the mandibular ramus, zygomatic arch, malar eminence, upper lip, chin, neck, and bone prominence of the forehead is at greater risk of scarring from laser resurfacing.30 Irradiation reduces the number of pilosebaceous units and causes endarteritis obliterans that reduces re-epithelialization, placing the patient at increased risk for scarring from laser resurfacing.

Acne Scar

Acne scarring can be a psychologically devastating problem for certain patients. It is imperative to impress on patients that such scarring can only be improved, not eliminated. Acne scarring results from acne vulgaris and cystic acne. Inciting factors include overgrowth of Propionibacterium acnes, overproduction of sebum, hyperkeratinization of follicular epithelium, and hormonal changes.55 The infectious nature of acne vulgaris causes dermal inflammation, which leads to destruction of collagen, dermal atrophy, and fibrosis, resulting in depressed or contracted scars.57 Atrophic scars result from collagen destruction in the dermis, which results in thinning of the dermis and is often associated with loss of subcutaneous fat.37 Atrophic scars appear concave, have thin skin covering them, and cast shadows in certain lighting.

Ice pick scars are another form of acne scarring. Many reports of treatment of ice pick acne scars have shown improvement with punch grafting followed by dermabrasion 6 to 8 weeks later. Ice pick scars can be initially excised with a skin punch and closed with 6-0 absorbable suture to convert a deep circular scar to a superficial circular scar that can then be more effectively dermabraded. Orentreich has advocated performing multiple stabs with a hypodermic needle tangentially beneath ice pick scars to release fibrous adhesions followed by resurfacing.58 When ice pick scars are too numerous to be excised individually and are confined to a limited area on the face, the scars may be excised as a group. This is accomplished by performing an elliptical excision of the scars parallel to RSTLs (Fig. 27-22). Nonablative lasers leave the epidermis intact and have been used to treat acne scars. The method of action includes thermal injury to the dermal collagen, which releases inflammatory mediators that activate fibroblasts, which in turn stimulates collagen remodeling.59

Keloid and Hypertrophic Scar

Scars are a natural part of healing, but when the maturation phase of wound healing does not subside within 9 to 12 months of wounding, the scar is considered exuberant.32 Keloid and hypertrophic scars arise from exuberant scars that are usually firm, raised, and erythematous, causing symptomatic complaints of pruritus and dysesthesias.32 The etiology of keloid and hypertrophic scarring is unknown but is believed to stem from excessive collagen synthesis and decreased collagen degradation in the process of wound healing.60,61 Excessive collagen production by fibroblasts may be related to high levels of cytokines.62 Keloids resemble hypertrophic scars but grow beyond the wound margin. They exhibit a prolonged proliferative phase resulting in the appearance of thick hyalinized collagen bundles.44 The appearance and thickness of hypertrophic scars typically improve during the course of a few years. This is not true of keloid scars.63

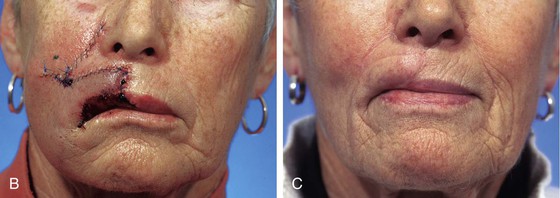

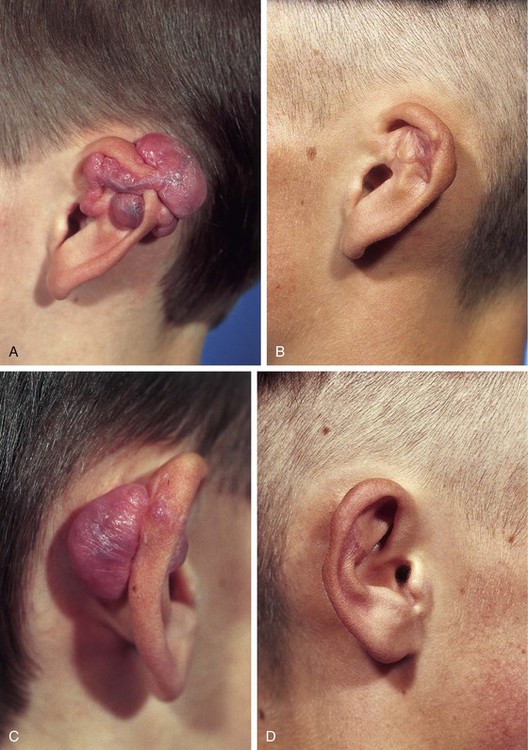

No single method is ideal for treatment of hypertrophic and keloid scars. The recurrence of the condition after excision can range from 45% to 100%.64 Most of the time, excision is preceded by serial intrascar injections of triamcinolone acetonide in an attempt to reduce the risk of recurrence.13 The appearance of hypertrophic and keloid scars can be improved with laser resurfacing as well as with intrascar injections of triamcinolone acetonide. Nonablative lasers have also been shown to improve the color and texture of keloid and hypertrophic scars.46,48 Compression of scars may induce flattening, and silicone sheeting can thin and soften these types of scars. Other treatment modalities include excision, cryosurgery, irradiation, compression therapy, and intrascar injections of interferon alfa-2b. Often a combined modality is the preferred treatment (Figs. 27-23 and 27-24).65

FIGURE 27-23 A, A 1 × 1.5-cm skin defect of upper lip repaired by primary wound closure. B, Postoperative view at 7 months. Hypertrophic scar and elevation of vermilion border have occurred. C, Scar treated with three injections of triamcinolone acetonide suspension (10 mg/mL) separated by intervals of 2 months followed by double Z-plasty. D, Z-plasties completed. E, Five months after Z-plasties.

FIGURE 27-24 A 14-year-old boy with bilateral keloids of auricles after reconstructive otoplasties. A-D, Preoperative views and 5 years after excision of keloids and postoperative serial injections of triamcinolone acetonide into scars.

Glucocorticoids have a profound anti-inflammatory effect. The most common form used is triamcinolone, which is injected into the depths of a scar. Scar injections of triamcinolone acetonide suspension are used to soften firm scars, to lower raised keloids, and to prevent their recurrence.66 Steroids decrease fibroblast proliferation, reduce blood vessel formation, and interfere with fibrosis by inhibiting extracellular matrix protein gene expression.67 When steroid injection is used at the time of keloid excision, it is injected at the wound margins immediately after excision. Repeated injection is performed at 3- to 6-week intervals.9 Multiple injections are usually necessary. Excessive steroid injection of scars can lead to skin atrophy, hypopigmentation, and telangiectasias.68

Scar Excision and Skin Grafting

There are situations in which scar contraction may result in distortion of facial structures. In other cases, scar contracture may cause stenosis of the nostril, mouth, or external auditory canal. In such cases, excision of scar tissue and resurfacing of the resulting wound with a full-thickness skin graft may improve the condition. Figure 27-25 shows an example of correcting stenosis of the right nostril and nasal vestibule. Scar tissue was excised from the anterior floor of the nose. This released the alar base, which was mobilized laterally, leaving a void of skin in the floor of the vestibule. An auricular cartilage graft measuring 3 × 0.5-cm was placed in the tissue void. It was oriented so that the longer dimension of the graft was horizontal. One end of the graft was braced against the nasal spine and the other end against the soft tissues of the alar base. The cartilage graft served as a splint against scar contraction and the subsequent medial migration of the alar base during healing. A full-thickness skin graft covered the exposed cartilage graft and open wound in the anterior floor of the nose. The senior author has successfully managed nasal vestibular stenosis in this manner.

FIGURE 27-25 Stenosis of nostril from scar. A, Scar tissue excised and ala mobilized laterally. Auricular cartilage graft placed in floor of nasal vestibule to maintain lateral position of ala. Cartilage graft spans gap between nasal spine and alar base (yellow line). B, Full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) used to cover wound resulting from scar excision. C, Gauze bolster used to secure full-thickness skin graft. D, E, Preoperative and 4-month postoperative views.

Nonsurgical Options and Fillers

Silicone sheets placed over scars have been used in the treatment of hypertrophic, keloid, and burn scars.69 The sheeting has been shown to improve scar thickness, size, color, and texture.61,70 This treatment is indicated for early erythematous hypertrophic or keloid scars, for burn scars, and as an adjunctive to other procedures.61 It is unknown exactly how the use of silicone sheeting improves the appearance of scars. Investigations have shown that scar improvement is not the result of pressure, change in scar temperature, or oxygen tension.71,72 Silicone gel sheeting is impermeable to water, preventing evaporation of water from the skin, and thus may serve to improve hydration as a result of occlusion of the treated area.73,74 An increase in hydration of subcutaneous tissue may have an effect on fibroblast activity.75 Hydration has been shown to inhibit fibroblast production of collagen and glycosaminoglycans in vitro.76 Silicone sheeting should be used at least 12 hours a day for 6 months. In a controlled setting, Gold et al73 demonstrated that the half of a wound on which silicone sheeting was placed healed better than the untreated half. Another study demonstrated that the use of silicone sheeting for 2 months after wounding decreased the incidence of hypertrophic scars compared with nontreated sites.77 For these reasons, the authors of this chapter initiate the use of sheeting as soon as the sutures are removed from a wound repair if we anticipate that incision lines may not mature into unobtrusive scars.

Glycosaminoglycan gel injected in the subcutaneous tissues in the revision of tethered scars has been reported to decrease scar contracture and to soften scars.78 Vitamin E is believed to improve scars, but the use of vitamin E too early in scar management may result in reduction of the tensile strength of the wound, which can lead to stretched scars and possible wound dehiscence.79 A double-blind study showed no improvement in the aesthetic appearance of surgical scars treated with a topical application of vitamin E.80 Topical vitamin A in the form of 0.05% retinoic acid has been shown to lower the level of elevated scars and to reduce pruritus of scars.81

Compression therapy consists of applying pressure to scars in an attempt to prevent the development of hypertrophic scars.82 Compression therapy may be accomplished with specially designed garments that are worn over scars for a prolonged interval. Constant pressure on the scar by the garment is thought to produce tissue hypoxia, reducing collagen synthesis.76

The aesthetic deformity of a scar is magnified if it is depressed or adherent to underlying fascia, which prevents the normal movement of underlying muscle. Soft tissue contour depressions have been corrected with dermal grafts, fat grafts, and a variety of synthetic substances.83 Autologous fat is an ideal material for filling depressions and contour deformities, but the degree of fat persistence after grafting is variable.84,85 Even though some of the fat may be resorbed, the remaining fat may help prevent the scar from readhering to the underlying fascia. The best donor site from which to harvest fat is the lateral thighs and abdomen. Fat is harvested by use of a large cannula with low-pressure suction in slow back-and-forth movements to reduce traumatic injury to the fat cells.86 Harvested fat should be washed and centrifuged. Oil, blood, and extracellular fluid are then separated from the fat cells. Fat is injected into the subcutaneous layer through small-bore cannulas. The mobility of the recipient bed can affect the survival of injected fat.87 The greater the movement of the recipient area from muscle contractions, the less is the survival of fat grafts.

In addition to fat, other injectable substances known as fillers include hyaluronic acid, calcium hydroxyapatite, and poly-L-lactic acid. These materials are injected into the dermal or immediate subdermal layer of the skin, whereas fat is injected into the subcutaneous tissue plane. Fat cannot be injected into the dermis. Dermal fillers can improve skin creases but do not work as well as fat for correction of contour depressions. The disadvantages of most dermal fillers are their temporary nature. In addition to the need for repeated injections, they have a potential for displacement of the substance into tissue surrounding the treated area.

Medical-grade makeup can camouflage and actually adhere to scars. Green-based concealer will cover red scars, and orange will cover blue pigment. Tattooing is a more permanent camouflage technique that can be useful for hypopigmented or abnormally pigmented scars. Scar hypopigmentation is due to a reduced number of melanocytes in the periphery and complete absence in the central areas of a scar.88 For tattooing of scars, medical-grade dyes are used that match the color of the skin adjacent to the scar.89 A color slightly darker than the natural skin tone is the best choice and minimizes the need for multiple sessions.90

Topical treatment of skin is often helpful in minimizing hyperpigmentation resulting from surgery or resurfacing procedures. Hydroquinone, kojic acid, retinoic acid, phenol, and alpha hydroxy acids have been used for this purpose.91 Hydroquinone produces a reversible depigmentation of the skin by inhibition of the enzymatic oxidation of tyrosine to DOPA and by suppression of other melanocyte metabolic processes.9 Tretinoin causes epidermal thickening, increased granular layer thickness, stratum corneum compaction, and decreased melanin content, which can lighten postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.9

Local Flap Refinement

Flap Contouring

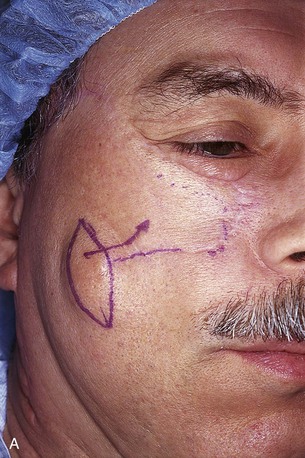

An important aspect of local flap surgery is contouring of the flap so that it assumes the natural topography of the recipient site. This becomes particularly important when a local flap is used to reconstruct an area of the face that manifests concave or convex surfaces or in areas where the native skin is thin or devoid of significant subcutaneous fat, such as the auricle (Fig. 27-26). Cutaneous flaps may often be thinned of accompanying subcutaneous fat when they are initially dissected if this is required for the flap to replicate in thickness the depth of the recipient site wound. In certain circumstances, it may be necessary to remove nearly all of the subcutaneous fat when the skin flap is transferred. Flaps that are excessively thick and cannot be thinned initially because of the risk of compromising vascularity may require additional contouring in a later surgical stage. This is especially true in situations in which thinning of the flap would be unwise, such as in patients who smoke, have peripheral vascular diseases or diabetes, or have been irradiated.92 Likewise, skin flaps may be dissected in a deep subcutaneous tissue plane when a thick cutaneous flap is advantageous. Thicker cutaneous flaps are often required for repair of skin defects that are accompanied by loss of subcutaneous fat and underlying muscle. Thus, the thickness of a local flap is often modulated by the surgeon at the time of flap dissection and transfer to restore a normal contour to the area of facial reconstruction.

FIGURE 27-26 A, B, Postauricular interpolated flap used to reconstruct defect of helix. Flap is bulky with step-off deformity at inferior aspect. C, D, Four months after contouring of flap and Z-plasty at inferior border of flap.

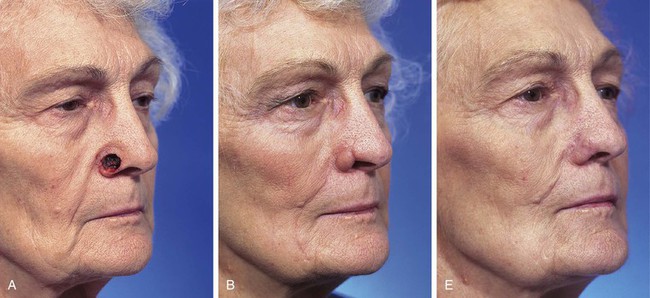

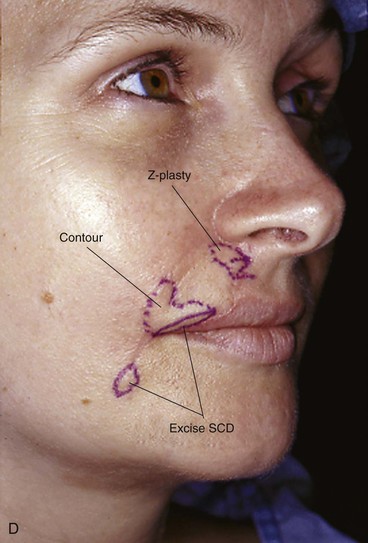

Skin defects of the nose reconstructed with interpolated cheek or forehead flaps frequently require a contouring procedure 4 to 6 months after inset of the flap. This is particularly true when flaps are required to repair defects of the ala, alar groove, or nasal sidewall. For instance, a contouring procedure to create an alar groove is a necessary third surgical stage in 75% of cases of alar reconstruction when an interpolated cheek or forehead flap is used for repair. Contouring of flaps used to reconstruct the nose is discussed in Chapters 13 and 18.

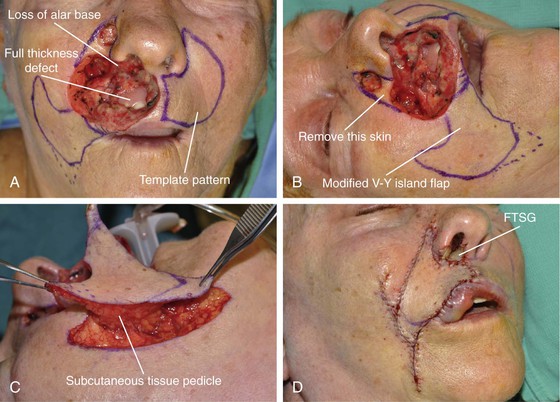

Skin defects of the ala that extend into the upper lip or alar-facial sulcus are a particular problem from the standpoint of restoring a convex contour to the ala while at the same time creating a concave contour to the reconstructed alar-facial sulcus. For this reason, defects that involve both the ala and cheek or lip are reconstructed with two or more independent local flaps. Each flap is used to repair the component of the defect that involves a single aesthetic region. This approach places the borders of the flap in aesthetic boundary lines for enhanced scar camouflage. More important, use of separate flaps to reconstruct the portion of a defect involving a given aesthetic region eliminates the requirement of transferring a flap across concave aesthetic boundary lines, obliterating the contour of the concavity. However, in spite of using separate cutaneous flaps, when defects involve the entire ala and extend into the cheek skin, it is usually necessary to perform a secondary contouring procedure to restore a natural topography to the alar-facial sulcus and to provide the best possible aesthetic result (Fig. 27-27).

FIGURE 27-27 A, A 3 × 4-cm skin and soft tissue defect of ala and medial cheek. Auricular cartilage graft in place for structural support of ala. Subcutaneous tissue pedicled cheek island flap designed for reconstruction of ala. Arrow indicates plan for cheek advancement flap to repair cheek component of defect. B, C, Advancement flap dissected and reflected superiorly. D, Island flap transposed to ala. Cheek flap advanced and sutured. E, F, Postoperative result at 2 months. Alar-facial sulcus has been obliterated by pedicle of island flap. G, Solid line outlines area of ala and broken line outlines area of advancement flap requiring contouring. H, Subcutaneous tissue removed during contouring of ala and medial cheek. I, J, Cotton bolster used to maintain constructed alar-facial sulcus. K-N, Preoperative and 3-month postoperative views after contouring procedure.

Contouring of a local flap usually is accomplished by a template to determine where to place incisions. A template is constructed of rubber foam sheeting or foil with use of the normal side of the face as the model for the template. Other times, incisions are simply made in old scars resulting from the initial reconstruction of the area. The skin of the flap is elevated in the subdermal or superficial subcutaneous tissue plane. The underlying scar tissue and subcutaneous fat are then sculpted by sharp dissection in an appropriate tissue plane to restore a natural topography to the area. This involves frequent replacement of the skin flap to its in situ position and assessment of the contour of the area covered by the flap. For areas that have a natural convex or flat surface, overcorrection during the contouring procedure is not necessary. For concave areas, such as the alar-facial and nasofacial sulci, slight overcorrection is recommended. That is, concave surfaces should be sculpted deeper than their normal contralateral counterpart. This is because scar deposition occurs after a contouring procedure, which tends to fill in concavities created by the surgeon. To retard this natural tendency toward obliteration of concavities as wounds heal, bolster dressings secured with percutaneous sutures are frequently employed for 5 days postoperatively. An alternative to bolster dressings is the use of quilting sutures, which consist of multiple full-thickness horizontal mattress sutures placed throughout the contoured area to eliminate surgical dead space and to maintain the contour of the area during the early phases of healing.

Trap-Door Deformity

Hematomas of the face resulting from blunt trauma may occasionally cause a trap-door deformity. This is presumably the result of the hematoma’s becoming organized, causing the resulting scar tissue to contract. In such instances, the trap-door deformity usually resolves over time but may require triamcinolone acetonide injections into the substance of the organized hematoma (Fig. 27-28). This type of deformity is not corrected with a resurfacing procedure such as dermabrasion and usually requires wide undermining of skin in the involved area and removal of underlying scar tissue if it does not respond to conservative management.

FIGURE 27-28 A, B, One month after blunt trauma to cheek of 12-year-old girl. Soft tissue hematoma organized and contracted, causing contour deformity that was accentuated on smiling. C, D, One year after three serial injections of hematoma with triamcinolone acetonide suspension (40 mg/mL) separated by intervals of 2 months.

When a contouring procedure is performed to correct a trap-door deformity or simply to improve the contour of a flap, incisions are made in the scars along the border of the flap (Fig. 27-29). A portion or all of the flap is elevated in a superficial subcutaneous tissue plane. A scalpel blade is positioned parallel to the skin surface in the immediate subdermal tissue plane and used to dissect the flap with a precise thickness.92 Fat and scar tissue from the deeper portion of the flap are left attached to underlying structures. The fat and scar tissue are then sculpted with a scalpel and scissors to remove redundant tissue. The overlying skin is allowed to settle over the contoured area to determine if additional subcutaneous tissue should be removed. The ultimate goal is to restore the level of the skin of the flap to that of the surrounding skin (Fig. 27-30). After a contouring procedure, a compression or bolster dressing is applied to the surgical area to prevent accumulation of blood beneath the undermined skin and for better adherence of the flap skin to the underlying soft tissues.

FIGURE 27-29 A, B, A 5 × 3-cm skin and muscle defect and a 2 × 1.8-cm mucosal defect of upper lip. Second 1 × 1-cm skin defect of alar-facial sulcus. Modified subcutaneous tissue pedicled V-Y island advancement flap designed for repair of wound. A template of the contralateral upper lip was used to design V-Y island flap. C, Flap based on subcutaneous tissue of medial cheek. D, Flap in place. Full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) in floor of nasal vestibule. E, Five months postoperatively. Scar revision surgery planned. Large Z-plasty incorporating right alar base used to displace alar base laterally. F, Auricular cartilage graft placed horizontally in floor of nasal vestibule after Z-plasty used to brace against scar contraction and possible displacement of alar base medially. G, Full-thickness skin graft placed in floor of nasal vestibule covering cartilage graft. Z-plasties and flap contouring completed. H-K, Before and 2 months after revision surgery.

FIGURE 27-30 A, A 2 × 2-cm skin defect of upper lip. Vertical lines mark planned skin excision to place scars in alar-facial sulcus. V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled island advancement flap designed for repair of wound. B, Flap in place. C, Four months postoperatively. Distortion of vermilion border, trap-door deformity of lateral flap, and persistent standing cutaneous deformity (SCD) of donor site scar are observed. D, Planned revision surgery. E, Revision surgery completed. F, Sixteen months after revision surgery.

When the scar surrounding a flap manifesting trap-door deformity is curvilinear, it is often helpful to integrate the skin of the flap with the adjacent facial skin by using multiple small Z-plasties (Fig. 27-31). The scar bordering the portion of the flap exhibiting the trap-door deformity is excised, and skin undermining is performed in the subcutaneous tissue plane for 1 to 2 cm on both sides of the scar. Multiple Z-plasties are designed along the length of the excised scar. Each triangular flap of the Z-plasty should measure 5 mm in length and have a 30° to 40° angle. The flaps are transposed and secured at each apex with a deep buried suture of 5-0 polydioxanone. A small cutting needle with a half-circle configuration is ideal for this purpose. The skin is approximated with interrupted simple or vertical mattress 5-0 or 6-0 cutaneous sutures. The wound is cared for in the standard manner, and sutures are removed in 5 to 7 days after the procedure. Dermabrasion of the scar and adjacent skin may be performed in 6 to 8 weeks after revision surgery.

FIGURE 27-31 A, Scar of healed bilobe nasal flap outlined by continuous blue line. Wider blue line at inferior border of flap indicates depressed scar marked for excision and double Z-plasties. Trap-door deformity outlined by broken line. B, Incision for contouring of flap made in scar at inferior border of flap. Subcutaneous tissue excised shown on surface of contoured area. Two Z-plasties (broken lines) performed at inferior incision line. C, Z-plasties completed. Bolster dressing in place. D, E, Before bilobe nasal flap and 6 months after contouring of flap.

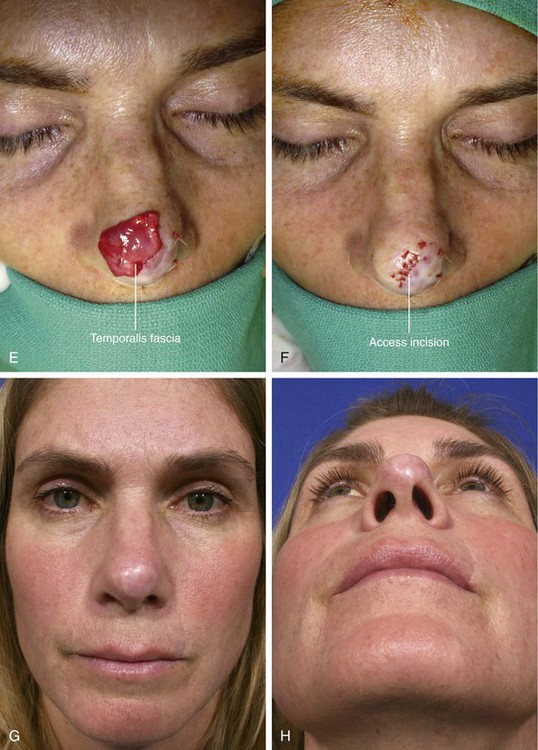

On occasion, there may be a persistent contour irregularity or depression of the surface of a flap after facial reconstruction. The majority of such deformities significantly improve with time. Should a depressed contour persist after transfer of a cutaneous flap or skin graft, it may be improved with grafts of fat, fascia, or dermal allografts placed beneath the skin in the area of the depressed contour (Fig. 27-32). An incision is made at the border of the flap or graft, and small Metzenbaum scissors are used to create a subcutaneous tissue pocket over the area of depression. Autogenous fascia, fat, or dermal allograft is positioned in the pocket to produce the desired contour elevation. The elevation should be slightly overcorrected to allow some absorption of the graft material. Large contour depressions, especially on the cheek, may sometimes be improved with a subcutaneous fat flap transfer to the depression from an adjacent area (Fig. 27-33). This is possible only in instances in which an adjacent area has an excess amount of subcutaneous fat that can be used for construction of the fat flap.

FIGURE 27-32 A, B, A 1.5 × 1.4-cm cutaneous defect of infratip lobule repaired with full-thickness skin graft. C, D, Postoperative result at 5 years. Contour depression causes unsightly appearance. E, Temporalis fascia graft before its insertion beneath healed skin graft. F, Fascia inserted beneath skin graft and access incision used to insert fascia graft closed. Sutures peripheral to access incision closure line used to secure fascia in place. G, H, Postoperative result at 3 months.

FIGURE 27-33 A, Persistent standing cutaneous deformity from large rotation advancement cheek flap marked by ellipse. Arrow indicates plans to transfer fat from beneath standing cutaneous deformity to fill depressed contour beneath distal portion of healed flap. Broken line indicates border of flap. B, Flap undermined. Standing cutaneous deformity elliptical island of skin removed, preserving underlying fat that was transferred medially as hinge flap to improve contour of medial cheek. C, Wound closed. D-G, Preoperative and 9-month postoperative views.

References

1. Clark, RA. Cutaneous tissue repair: basic biologic consideration. I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985; 13:701.

2. Thomas, JR, Prendiville, S. Update in scar revision. Facial Plast Surg. 2002; 10:103.

3. Moran, ML. Scar revision. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2001; 34:767.

4. Terris, DJ. Dynamics of wound healing. In: Baily BJ, ed. Head & neck surgery—otolaryngology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998:219.

5. McGillis, ST, Lucas, AR. Scar revision. Dermatol Clin. 1998; 16:165.

6. Leach, J. Proper handling of soft tissue in the acute phase. Facial Plast Surg. 2001; 17:227.

7. Horswell, BB. Scar modification. Techniques for revision and camouflage. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Clin North Am. 1998; 6:55.

8. Tardy, ME, Thomas, JR, Paschow, MS. The camouflage of cutaneous scars. Ear Nose Throat J. 1981; 60:61.

9. Zakkak, TB, Griffin, JE, Max, DP. Posttraumatic scar revision: a review and case presentation. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma. 1998; 4:35.

10. Clark, RA. Biology of dermal wound repair. Dermatol Clin. 1993; 11:647.

11. Thomas, JR, Hochman, M. Scar camouflage. In: Baily BJ, ed. Head & neck surgery—otolaryngology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998:2026.

12. Yarborough, JM. Ablation of facial scars by programmed dermabrasion. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988; 14:292.

13. Kaplan, B, Potter, T, Moy, RL. Scar revision. Dermatol Surg. 1997; 23:435.

14. Engrave, LH, Gottlieb, JR, Millard, SP, et al. A comparison of intramarginal and extramarginal excision of hypertrophic burn scars. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988; 81:40.

15. Yang, JY. Intrascar excision for persistent perioral hypertrophic scar. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996; 98:1200.

16. Dzubow, LM. Scar revision by punch graft transplants. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1985; 11:1200.

17. Regan, JR, Frost, TW. Scar revision and camouflage. In: Baker SR, Swanson NA, eds. Local flaps in facial reconstruction surgery. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995:587.

18. Mostafapour, SP, Murakami, CS. Tissue expansion and serial excision in scar revision. Facial Plast Surg. 2001; 17:245.

19. Karounis, H, Gouin, S, Eisman, H, et al. A randomized, controlled trial comparing long-term cosmetic outcomes of traumatic pediatric laceration repaired with absorbable plain gut versus nonabsorbable nylon sutures. Acad Emerg Med. 2004; 11:730.

20. Singer, AJ, Hollander, JE, Quinn, JV. Evaluation and management of traumatic lacerations. N Engl J Med. 1997; 337:1142.

21. Holt, GR. Treatment of trapdoor scars. In: Thomas JR, Holt GR, eds. Facial scars: incision, revision, and camouflage. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1989.

22. Rodgers, BJ, Williams, EF, Hove, CR. W-plasty and geometric broken line closure. Facial Plast Surg. 2001; 17:239.

23. Borges, AF. Improvement of antitension lines scar by the “W-plastic” operation. Br J Plast Surg. 1959; 12:29.

24. Borges, AF. Preoperative planning for better incisional scars. In: Thomas JR, Holt GR, eds. Facial scars: incision, revision and camouflage. St. Louis: Mosby; 1989:44.

25. Key, SJ, Thomas, DW, Shepherd, JP. The management of soft tissue facial wounds. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995; 33:76.

26. Harmon, CB, Zelickson, BD, Roenigk, RK, et al. Dermabrasion after scar revision. Dermatol Surg. 1995; 21:503.

27. Katz, B, Oca, A. A controlled study of the effectiveness of spot dermabrasion on the appearance of surgical scars. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991; 24:462.

28. Yarborough, JM. Ablation of facial scars by programmed dermabrasion. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988; 14:292.

29. Collins, PS, Farber, GA. Postsurgical dermabrasion of the nose. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1984; 10:476.

30. Bradley, DT, Park, SS. Scar revision via resurfacing. Facial Plast Surg. 2001; 17:253.

31. Gold, MH. Dermabrasion in dermatology. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003; 4:467.

32. Capon, A, Mordon, S. Can thermal lasers promote skin wound healing. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003; 4:1.

33. Anderson, RR, Parrish, JA. Selective photothermolysis: precise microsurgery by selective absorption of pulsed radiation. Science. 1983; 220:524.

34. Ho, C, Nguyen, Q, Lowe, NJ, et al. Laser resurfacing in pigmented skin. Dermatol Surg. 1995; 21:1035.

35. Berstein, LJ, Kauvar, AN, Grossman, MC, et al. Scar resurfacing with high-energy, short-pulsed and flash scanning carbon dioxide lasers. Dermatol Surg. 1998; 24:101.

36. Cotton, J, Hood, AF, Gonin, R, et al. Histologic evaluation of preauricular and postauricular human skin after high-energy, short-pulse carbon dioxide laser. Arch Dermatol. 1996; 132:425.

37. Tanzi, EL, Alster, TS. Treatment of atrophic facial acne scars with a dual-mode Er:YAG laser. Dermatol Surg. 2002; 28:551.

38. Nehal, KS, Levine, VJ, Ross, B, Ashonoff, R. Comparison of high-energy pulsed carbon dioxide laser resurfacing and dermabrasion in the revision of surgical scars. Dermatol Surg. 1998; 24:647.

39. Kwon, SD, Kye, YC. Treatment of scars with a pulsed Er:YAG laser. J Cutan Laser Ther. 2000; 2:27.

40. Walsh, JT, Flotte, TJ, Deutsch, TF. Er:YAG laser ablation of tissue: effect of pulse duration and tissue type on thermal damage. Lasers Surg Med. 1989; 9:314.

41. Kye, YC. Resurfacing of pitted facial scars with Er:YAG laser. Dermatol Surg. 1997; 23:880.

42. Sawcer, D, Lee, HR, Lowe, NJ. Lasers and adjunctive treatments for facial scars. J Cutan Laser Ther. 1999; 1:77.

43. Zachary, CB. Modulating the Er:YAG laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2000; 26:223.

44. Tanzi, EL, Alster, TS. Laser treatment of scars. Skin Therapy Lett. 2004; 9:4.

45. Paquet, P, Hermanns, JF, Piérard, GE. Effect of the 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser for the treatment of keloids. Dermatol Surg. 2001; 27:171.

46. Alster, TS, Lewis, AB, Rosenback, A. Laser scar revision: comparison of CO2 laser vaporization with and without simultaneous pulsed dye laser treatment. Dermatol Surg. 1998; 24:1299.

47. Arian, L, Lask, G. Treatment of hypertrophic scars and keloids with laser. In: Lask G, Lowe NJ, eds. Lasers in cutaneous and cosmetic surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1999.

48. Alster, TS. Improvement of erythematous and hypertrophic scars by the 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. Ann Plast Surg. 1994; 32:186.

49. Goldman, MP, Fitzpatrick, RE. Laser treatment of scars. Dermatol Surg. 1995; 21:685.

50. Goldberg, DJ. Full-face nonablative dermal remodeling with a 1320 nm Nd:YAG laser. Dermatol Surg. 2000; 26:915.

51. Goldberg, DJ. New collagen formation after dermal remodeling with an intense pulsed light source. J Cutan Laser Ther. 2000; 2:59.

52. Bitter, PJ. Noninvasive rejuvenation of photoaged skin using serial, full-face IPL treatments. Dermatol Surg. 2000; 26:835.

53. Zelickson, BD, Kilmer, SL, Bernstein, E, et al. Pulsed dye laser therapy for sun damaged skin. Lasers Surg Med. 1999; 25:229.

54. Lupton, JR, Williams, CM, Alster, TS. Nonablative laser skin resurfacing using a 1540 nm erbium glass laser: a clinical and histological analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2002; 28:833.

55. Sadick, NS, Schecter, AK. A preliminary study of utilization of the 1320-nm Nd:YAG laser for the treatment of acne scarring. Dermatol Surg. 2004; 30:995.

56. Tanzi, EL, Alster, TS. Comparison of the 1450-nm diode laser and 1320-nm Nd:YAG laser in the treatment of atrophic facial scars: a prospective clinical and histologic study. Dermatol Surg. 2004; 30:152.

57. Rogachefsky, AS, Hussain, M, Goldberg, DJ. Atrophic and mixed pattern of acne scars improved with a 1320-nm Nd:YAG laser. Dermatol Surg. 2003; 29:904.

58. Orentreich, D, Orentreich, N. Subcutaneous incisionless surgery for the correction of depressed scars and wrinkles. Dermatol Surg. 1995; 1:543.

59. Levit, E, Daly, D, Scarborough, DA, et al. The case for nonablative laser resurfacing. Cosmetic Dermatol. 2002; 15:39.

60. Warschaw, KE, McCullough, M. Disorders of collagen. In: Farmer ER, Hood AF, eds. Pathology of the skin. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999:661.

61. Dockery, GL, Nilson, RZ. Treatment of hypertrophic and keloid scars with Silastic gel sheeting. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1994; 33:110.

62. Ghahary, A, Shen, YJ, Scott, PG, et al. Enhanced expression of mRNA for transforming growth factor-beta, type I and type II procollagen in human post-burn hypertrophic scar tissues. J Invest Dermatol. 1993; 122:465.

63. Murray, JD, Pollack, SV, Purnell, SR. Keloids: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981; 4:461.

64. Berman, B, Bieley, HC. Adjunct therapy to surgical management of keloids. Dermatol Surg. 1996; 22:126.

65. Alster, T. Laser scar revision. Dermatol Surg. 2003; 29:25.

66. Ketchum, LD, Robinson, DW, Masters, FW. The treatment of hypertrophic scar, keloid, and scar contracture by triamcinolone acetonide. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966; 38:209.

67. Su, CW, Alizadeh, K, Boddie, A, et al. The problem scar. Clin Plast Surg. 1998; 25:451.

68. Goett, Dr, Odom, RB. Adverse effects of corticosteroids. Cutis. 1979; 23:477.

69. Perkins, K, Davey, RB, Wallis, KA. Silicone gel: a new treatment for burn scars and contractures. Burns. 1982; 9:406.

70. Chang, CW, Ries, WR. Nonoperative techniques for scar management and revision. Facial Plast Surg. 2001; 17:283.

71. Quinn, KG. Silicone gel in scar treatment. Burns. 1987; 13:S33.

72. Sawada, Y, Urushidate, S, Nihei, Y. Hydration and occlusive treatment of a sutured wound. Ann Plast Surg. 1998; 41:508.

73. Gold, MH, Foster, TD, Adair, MA, et al. Prevention of hypertrophic scars and keloids by the prophylactic use of topical silicone gel sheets following a surgical procedure in an office setting. Dermatol Surg. 2001; 27:641.

74. Katz, B. Silicone gel sheeting in scar therapy. Cutis. 1995; 56:65.

75. Fulton, VE. silicone gel sheeting for the prevention and management of evolving hypertrophic and keloid scars. Dermatol Surg. 1995; 21:947.

76. Chang, CC, Kuo, TF, Chiu, HC, et al. Hydration, not silicone modulates the effects of keratinocytes on fibroblasts. J Surg Res. 1995; 59:705.

77. Cruz-Korchin, NI. Effectiveness of silicone sheets in the prevention of hypertrophic breast scars. Ann Plast Surg. 1996; 37:345.

78. Boyce, DE, Bantick, G, Murison, MSC. The use of ADCON-T/N glycosaminoglycans gel in the revision of tethered scars. Br J Plast Surg. 2000; 53:403.

79. Widgerow, AW, Chait, LA, Stals, R, et al. New innovations in scar management. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2000; 24:227.

80. Jenkins, M, Alexander, JW, MacMillan, B, et al. Failure of topical steroids and vitamin E to reduce postoperative scar formation following reconstructive surgery. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1986; 7:309.

81. Janssen de Limpens, AM. The local treatment of hypertrophic scars and keloids with topical retinoic acid. Br J Dermatol. 1980; 103:319.

82. Ng, CL, Lee, St, Wong, KL. Pressure garments in the prevention and treatment of keloids. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1983; 12:430.

83. Dzubow, LM. Scar revision by punch-graft transplants. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1985; 11:131.

84. Coleman, SR. Facial recontouring with lipostructure. Clin Plast Surg. 1997; 24:347.

85. Benito, JD, Fernandex, I, Nanda, V. Treatment of depressed scars with a dissecting cannula and an autologous graft. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1999; 23:367.

86. Boyce, RG, Nuss, DW, Kluka, EA, et al. Use of autogenous fat, fascia, and nonvascularized muscle grafts in the head and neck. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1994; 27:39.

87. Illouz, YG. Present results of fat injection. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1988; 12:175.

88. Breathnach, AS. Melanocytes in early regenerated human epidermis. J Invest Dermatol. 1960; 35:245.

89. Guyuron, B, Vaughan, C. Medical-grade tattooing to camouflage depigmented scars. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995; 95:575.

90. Spear, SL, Convit, R, Little, JW. Intradermal tattoo as an adjunct to nipple-areola reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989; 83:907.

91. Kaplan, B, Potter, T, Moy, R. Scar revision. Dermatol Surg. 1997; 23:435.

92. Baker SR, ed. Principles of nasal reconstruction, 2nd ed, New York: Springer, 2011.