CHAPTER 29 Scapulothoracic Burscoscopy

The scapulothoracic articulation plays a crucial role in the motion of the upper extremity. There are multiple disorders that affect this articulation and cause snapping scapula. Snapping scapula may be secondary to scapulothoracic bursitis, scapular osteochondromas or elastofibromas, scapular winging, scapulothoracic dyskinesia, and/or Sprengel’s deformity. The term snapping scapula is somewhat of a misnomer because not all disorders of the scapulothoracic joint make a characteristic snapping sound. As the understanding of snapping scapula improves, more cases are being diagnosed and treated. In most cases, conservative management is successful.1 However, patients who fail conservative management may be treated with open or arthroscopic surgery. Historically, surgical procedures described were open procedures2–8 or a combined open and arthroscopic procedure.4 An all-arthroscopic procedure was initially described by Cuillo in 1992 and the first series was later published by Harper and colleagues.2,10 Scapulothoracic burscoscopy provides a safe alternative to open superomedial angle resection, bursectomy, and excision of an elastofibroma or osteochondroma.

ANATOMY AND PATHOANATOMY

Anatomy

The scapula is a triangular-shaped bone that articulates with the humerus and clavicle laterally and thorax ventrally. Its only attachment to the axial skeleton is the acromioclavicular joint. The scapula is integral to motion of the shoulder because it provides a congruous joint for humeral articulation, glides on the thorax to position the glenoid in space,12 and serves as a stable base for the origin and insertion of multiple muscles that control scapular and humeral motion.

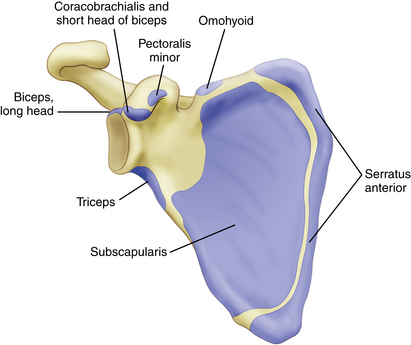

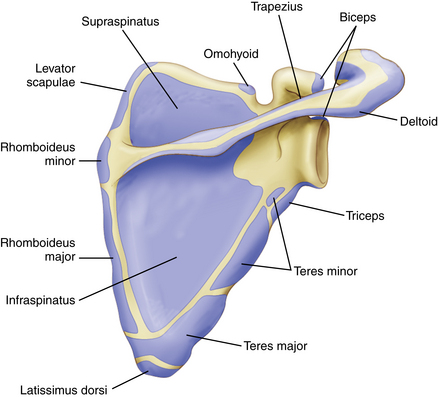

Seventeen muscles have their origins or insertions on the scapula (Box 29-1). The subscapularis muscle covers the anterior surface of the scapula and the supraspinatus and infraspinatus cover the posterior surface in the supraspinatus and infraspinatus fossa, respectively. The scapular spine and acromion provide the origin of the deltoid muscle and an insertion for the trapezius muscle. On the medial border, the serratus anterior, levator scapulae, and rhomboid major and minor muscles attach to the scapula. The lateral border is the origin of the triceps, teres major, and teres minor muscles. Inferiorly, the latissimus dorsi muscles attaches to the inferior angle of the scapula. Other muscle attachments include the omohyoid, long head of the biceps, coracobrachialis, short head of the biceps, and pectoralis minor muscles (Figs. 29-1 and 29-2).

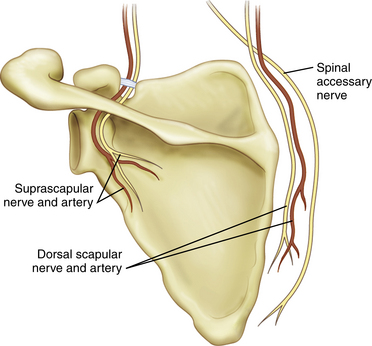

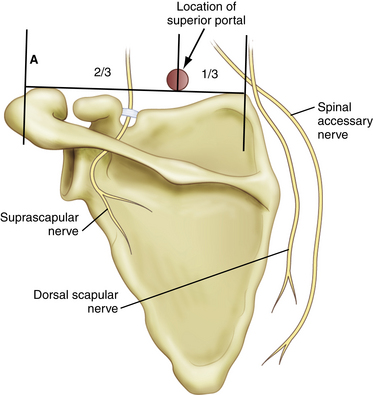

The neurovascular structures that are in proximity to the scapula include the suprascapular nerve and artery, dorsal scapular nerve and artery, transverse cervical artery, spinal accessory nerve, and long thoracic nerve. The suprascapular nerve travels through the suprascapular notch and suprascapular artery over the transverse scapular artery to continue laterally around the spine of the scapula and through the spinoglenoid notch into the infraspinatus fossa. The dorsal scapular nerve dorsal scapular artery,13 and spinal accessory nerve (cranial nerve IX) travel parallel to the medial border of the scapula. Understanding these relationships will allow safe portal placement and minimize the risk of injury to important neurovascular structures when performing scapulothoracic burscoscopy (Fig. 29-3).

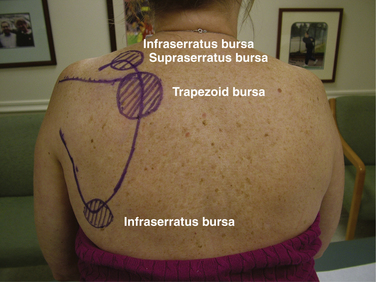

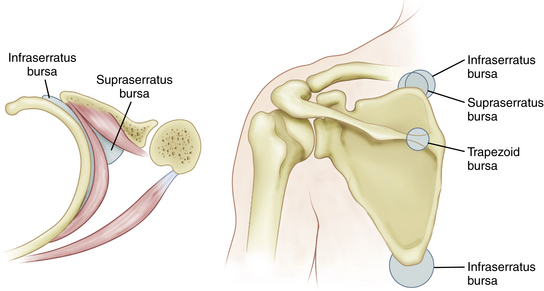

There are two major anatomic bursa and four minor adventitial bursae of clinical significance. The anatomic bursae are the supraserratus bursa, which is located between the subscapularis and serratus anterior muscles, and the infraserratus bursa, which is located between the serratus anterior muscle and chest wall.1,3,6,11,14 These bursae have been consistently located in both cadaveric specimens and during arthroscopic procedures (Table 29-1; Figs. 29-4 and 29-5).

| Bursae | Location |

|---|---|

| Supraserratus bursa | Between serratus anterior and subscapularis muscles |

| Infraserratus bursa | Between chest wall and serratus anterior muscle |

| Supraserratus bursa (superomedial angle) | Between serratus anterior and subscapularis muscles |

| Infraserratus bursa (superomedial angle) | Between chest wall and serratus anterior muscle |

| Infraserratus bursa (inferior angle of scapula) | Between chest wall and serratus anterior muscle |

| Trapezoid bursa | Between spine of the scapula and trapezius muscle |

FIGURE 29-4 Major (anatomic) and minor (adventitial) bursae of the scapulothoracic joint and its orientation in relation to the chest wall, scapula, serratus anterior muscle, and subscapularis muscle.

(Adapted from Kuhn JE, Hawkins J. Evaluation and treatment of scapular disorders. In: Warne JJP, Iannotti JP, Gerber C, eds. Complex and Revision Problems in Shoulder Surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:357-375.)

In addition, four adventitial bursae have been described. These are thought to develop as a result of scapulothoracic dyskinesia and are not consistently seen. The supraserratus and infraserratus bursae (minor) are located ventral to the superomedial angle of the scapula. A second infraserratus bursa is located anterior to the inferior angle of the scapula. The trapezoid bursa is located dorsal to the spine of the scapula.14

Pathoanatomy

The differential diagnosis of snapping scapula can be divided into bony or soft tissues disorders. However, this categorization is purely arbitrary because bony causes may play a role in soft tissue disorders. Changes in bony anatomy of the scapula and thus incongruity of the scapulothoracic joint may cause a snapping scapula. Osteochondromas, Luschka’s tubercle, hooking of the superomedial scapula, elastofibroma, malunion of scapular or rib fractures, and callous formation after scapular or rib fractures have been reported to be a cause of the snapping scapula.1,5,6,8,15-18 The resultant change in anatomy may create sounds that vary from a barely audible friction rub to a loud snapping sound.5,20–22 There is no consensus on whether anatomic changes or the resulting bursitis are the source of the periscapular pain.

In addition to soft tissue and bursal inflammation,21 scar formation after periscapular muscle avulsions may cause incongruity between the scapula and chest wall and cause periscapular crepitus or an audible snapping sound. However, symptomatic bursitis does not necessarily have an accompanying audible sound. On the contrary, a snapping scapula is not necessarily symptomatic and thus may not be clinically significant.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The patient with a symptomatic snapping scapula often gives a history of a traumatic event or a repetitive upper extremity activity.4,10,23–28 The traumatic event may involve a protraction or retraction movement of the scapula, direct blow to the scapula, fracture of the scapula, or fracture of the underlying rib cage. Sports requiring repetitive or forceful shoulder activities including baseball pitching, swimming, weight training, gymnastics, football, and fencing may produce the symptoms of snapping scapula.

Regardless of the underlying pathology, most patients report having crepitus—grinding, grating, clicking, or crunching with shoulder motion.5,6,17,30 The audible snap may or may not be painful.31 We have noted that the crepitus associated with bursitis is less severe than crepitus or snapping caused by bony lesions.20 Pain is often localized to the superomedial angle or medial border of the scapula, but pain at the inferior angle of the scapula is more typical in overhead athletes.28 Patients commonly report pain that is worsened with overhead activities, irrespective of the location of the inflamed bursa. Some patients may report a family history of similar symptoms.23

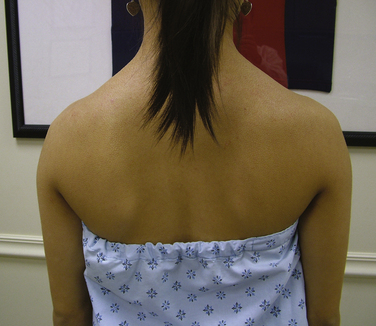

Physical examination findings associated with disorders of the scapulothoracic articulation can vary from near-normal to severe scapular winging and crepitus. Inspection of the posterior aspect of the shoulders may reveal subtle asymmetry. The dominant shoulder is frequently slightly depressed compared with the contralateral shoulder.32 This is a normal finding in many active individuals and athletes and is not directly related to a snapping scapula (Fig. 29-6).

Many patients will complain of tenderness over an inflamed bursa, with the supraserratus and infraserratus bursae adjacent to the superomedial angle the most common area affected.5-7,28,31 An audible grinding noise or snap can be reproduced with active shoulder range of motion. These sounds have been described as froissement (gentle friction sound), frottement (a course friction or grating sound), and craquement (loud snapping sound). This distinction is clinically important because froissement almost always responds to nonoperative treatment whereas craquement is usually pathologic and requires operative intervention. In contrast to range of motion of the shoulder, isometric contraction of the rhomboid muscles typically does not produce these characteristic sounds.30 When present, the dyskinesia of scapular winging can cause scapulothoracic bursitis. A full range of motion of the shoulder is normally seen; however, there has been a case report of scapulothoracic bursitis that resulted in a significant decrease in shoulder motion.4 Thoracic scoliosis and kyphosis change the scapulothoracic articulation and have also been reported as a cause for symptomatic snapping scapula (Box 29-2).30

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Radiographs should consist of a true anteroposterior (AP) view of the scapula, lateral view of the scapula, and axillary view of the shoulder.20,26,29 These views will identify anatomic or bony abnormalities of the scapula causing scapulothoracic incongruity.

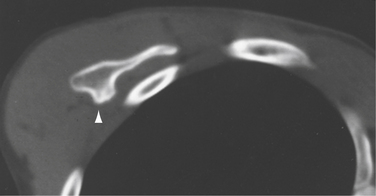

Although computed tomography (CT) has been shown to be useful for further evaluation of the shape of the scapula and narrowing of the scapulothoracic joint,20,29 some authors no longer use CT scans routinely because of the low yield and subjectivity of the findings.4,10 Mozes and associates33 used three-dimensional CT images to evaluate patients with suspected bony incongruity based on x-rays and CT scans. They found incongruity in 100% of the scapulae that they evaluated (Fig. 29-7). However, these results have not been replicated by others.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation may show the location and presence of bursal inflammation.10 We have found that MRI evaluation of the shoulder and cervical spine may be useful in ruling out associated pathology.

In patients with scapular winging, electromyographic studies should be performed to evaluate possible neuropathy.29 Lower cervical spine pathology is a common source of pain in the posterior aspect of the shoulder and should be further evaluated if pathology is suspected.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Nonoperative Treatment

Initial management of most patients should consist of rest, abstaining from exacerbating activities, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, postural training, and physical therapy, which is successful for most patients.1,4,10,20,26,30,34 Physical therapy should focus on periscapular muscle retraining and strengthening, with the inclusion of a program focused on improving core strength (Figs. 29-8 and 29-9).25,29,35 Most authors agree that nonoperative treatment of snapping scapula from structural causes is less likely to respond to nonoperative management and is an indication to proceed with operative intervention.

Injections into the inflamed bursa with a corticosteroid and local anesthetic may be diagnostic and therapeutic. A patient who fails nonoperative therapy but has a recurrence of symptoms after successful injection is considered a candidate for operative intervention, which can be extremely beneficial in resolving symptoms and returning the patient expediently to activities.4,20,25,27,29,34 Failure to respond to injections is considered a contraindication for operative treatment and a further diagnostic workup is necessary.4 In patients who fail to respond to injections, pathology involving the glenohumeral joint, suprascapular nerve, or cervical spine should be investigated. Patients involved in litigation, workers’ compensation, or a history of psychiatric illness, and those with voluntary snapping, should be very critically evaluated prior to considering operative intervention.21,29

Operative Management

There are many operative procedures for treating snapping scapula and scapulothoracic bursitis. Initially, open superomedial angle resection was described for the treatment of bony abnormalities of the scapulothoracic articulation.2–8,35 Isolated open bursectomy for symptomatic bursitis without bony abnormalities has been advocated by others.25,26,28,36 Comparison of open bursectomy and superomedial angle excision to arthroscopic bursectomy combined with open superomedial angle excision within a single patient population was found to have equivalent results.4 Good outcomes from all-arthroscopic techniques for bursectomy and superomedial angle excision have been reported.1,10,33,37 However, outcomes have only been described in case reports and small series. We advocate an all-arthroscopic bursectomy for symptomatic bursitis and concomitant superomedial angle resection if there is scapulothoracic incongruity present.

Arthroscopic Technique

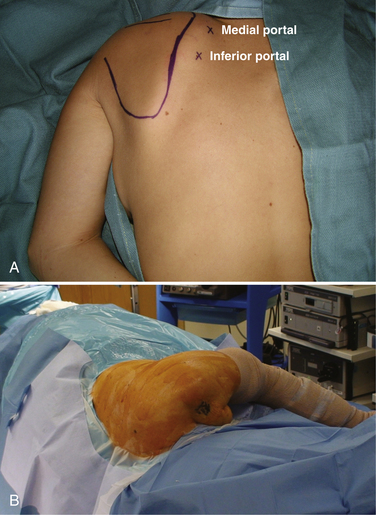

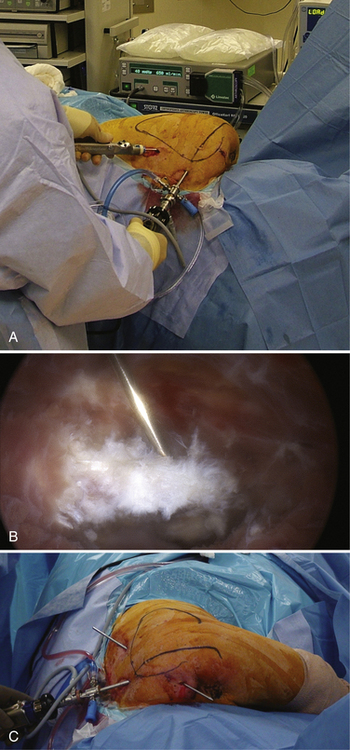

Arthroscopic burscoscopy can be performed in the prone or lateral position (Fig. 29-10). Prone positioning allows easier entry into the bursal space because of the increased scapular protraction. The disadvantage to the prone position is that the patient must be repositioned if glenohumeral or scapulohumeral arthroscopy is planned. Using the lateral position allows for glenohumeral and scapulohumeral arthroscopy without repositioning. However, it is more difficult to perform scapulothoracic burscoscopy because gravity pulls the scapula medially and thus restricts the scapulothoracic interval. An assistant can be helpful for proper arm orientation in either position, but is essential in the lateral position. The arm is draped free with the thorax drapes placed lateral to the spinous processes of the contralateral side and 15 cm below the inferior angle of the ipsilateral scapula.

The bony anatomy is drawn out in detail and the portal sites are marked. The standard initial viewing portal is made 2 cm medial to the medial scapular border at the level of the scapular spine. A working portal is then placed on a line that is drawn 2 to 3 cm medial and parallel to the medial scapular border. This portal is usually 4 to 6 cm inferior to the initial portal (Fig. 29-11). This can be adjusted inferiorly or superiorly based on the size of the patient. Alternatively, the more inferior portal can be used as the viewing portal and the more superior portal can be used as the working portal. The approximate site of the superior portal, as described by Chan and coworkers,38 should be marked prior to beginning the procedure. Marking the approximate position prior to tissue edema from fluid extravasation is essential and will limit the risk of neurovascular injury caused by improper placement. This portal should be located at the intersection of a line dividing the medial third and lateral two thirds of the scapula and 1 to 2 cm superior to the superior border of the scapula. This point allows a safe distance from the portal to the suprascapular nerve laterally and the spinal accessory nerve and dorsal scapular nerves and artery medially (Fig. 29-12).

The arm is placed in internal rotation and extension, the so-called chicken wing position” (Fig. 29-13). We do not recommend injecting saline into the serratus anterior space prior to inserting the arthroscope, because it does not help visualization. A blunt trocar is placed into the serratus anterior space, making sure to aim posteriorly away from the chest wall and taking care not to aim too laterally into the subscapularis space. Sweeping the bursa with the trocar creates a space for visualization, similar to clearing the subacromial space. A 30-degree 4.5-mm arthroscope is placed in to the serratus anterior space. To limit excessive tissue swelling and fluid extravasation, we recommend maintaining the fluid pressure at 50 mm Hg or lower. Occasionally, the fluid pressure may need to be raised for better visualization; however, it should be lowered below 50 mm Hg as soon as possible.

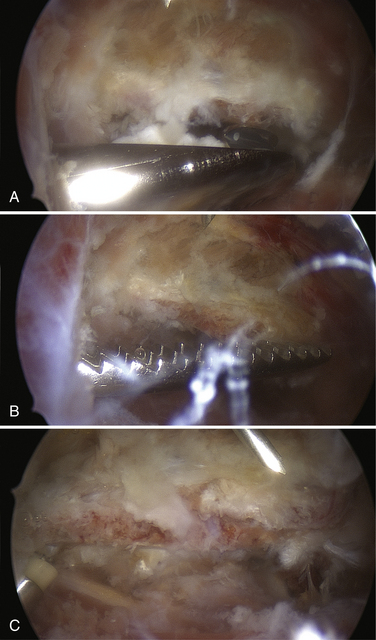

The inferior working portal is created using spinal needle localization. This portal can be made anywhere along the line described previously and established with a 4.5-mm cannula. The bursa is débrided with a full-radius resector (Fig. 29-14A). After the bursa is resected, the superior medial angle should be localized with a spinal needle (see Fig. 29-14B). The medial attachment of the supraspinatus, superomedial attachment of the serratus anterior, and lateral attachment of the rhomboid minor and levator scapulae muscles should be elevated using an arthroscopic radiofrequency ablation device. If there is difficulty resecting the tissue along the superior medial angle, the superior portal may be helpful. This portal is made using an inside-out technique. We place a trocar through the initial viewing portal, aiming under the superior medial border of the scapula toward the point superior to the scapula and one third the distance from the medial scapular border to the acromion, as described earlier (see Fig. 29-14C).

For bony incongruity of the scapulothoracic joint, an arthroscopic burr is used to resect the bony lesion and coplane the superomedial angle of the scapula using a cutting block technique, similar to that used for acromioplasty (Fig. 29-15A). This is completed while viewing through the medial portal, and the burr is placed through the inferior portal. We suggest removing sufficient bone to restore a smooth and congruent scapulothoracic articulation. A nasal rasp is inserted via a medial portal and used to complete the superomedial angle resection and smooth any rough edges (see Fig. 29-15B and 15C). We place a spinal needle into the bursal space for injection of a local anesthetic and corticosteroid after completion of the procedure.

Prior to removing the arthroscope, all fluid is suctioned from the bursal spaces. The portal sites are closed with a subcuticular suture and Steri-Strips. Injection of a local anesthetic and corticosteroid through the spinal needle into the area of the débrided bursa and resected superomedial angle of the scapula provides postoperative pain relief and, in our experience, decreases the time to return to pain-free range of motion.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

PEARLS

PITFALLS

SUMMARY

Snapping scapula is a well-described condition that can cause prolonged limitations in activities and persistent scapular pain. Traditionally, open techniques were used to treat cases that did not respond to conservative management. We believe that scapulothoracic burscoscopy offers a safe and efficacious alternative for treatment of snapping scapula and scapulothoracic bursitis, scapular osteochondromas, and elastofibromas with similar results to those of open procedures, with less morbidity and faster return to sports and activities of daily living.

1. Cuillo JV, Jones E Subscapular bursitis: conservative and endoscopic treatment of “snapping scapula” or “washboard syndrome”. Orthop Trans, 16; 1992:740.

2. Butters KP. The scapula. In: Rockwood CA, Matsen FA, editors. The Shoulder. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990:335-366.

3. Kouvalchouk JF. Subscapular crepitus. Orthop Trans. 1985;9:587-588.

4. Lehtinen JT, Macy JC, Cassinelli E, Warner JJ The painful scapulothoracic articulation: surgical management. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 423; 2004:99-105.

5. Milch H. Partial scapulectomy for snapping of the scapula. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1950;32:561-566.

6. Milch H. Snapping scapula. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1961;20:139-150.

7. Richards RR, McKee MD. Treatment of painful scapulothoracic crepitus by resection of the superomedial angle of the scapula. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;247:111-116.

8. Strizak AM, Cowen MH. The snapping scapula syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:941-942.

9. Wood VE, Verska JM. The snapping scapula in association with the thoracic outlet syndrome. Arch Surg. 1989;124:1335-1337.

10. Harper GD, McIlroy S, Bayley JI, Calvert PT Arthroscopic partial resection of the scapula for snapping scapula: a new technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 8; 1999:53-57.

11. Ruland LJ, Ruland CM, Matthews LS. Scapulothoracic anatomy for the arthroscopist. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:52-56.

12. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology part IIIthe SICK scapula dyskinesis, the kinetic chain, and rehabilitation. Arthroscopy, 19; 2003:641-661.

13. Butters K. Fractures of the scapula. In: Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown C, editors. Fractures in Adults. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2006:1257-1284.

14. Codman EA. Rupture of the supraspinatus tendon and other lesions in or about the subdeltoid bursa. In: Codman EA, editor. The Shoulder. Malabar, Fla: Krieger; 1984:123-177.

15. Carlson HL, Haig AJ, Stewart DC Snapping scapula syndrome: three case reports and an analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 78; 1997:506-511.

16. Fukunaga S, Futani H, Yoshiya S. Endoscopically assisted resection of a scapula osteochondroma causing snapping scapula syndrome. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:37.

17. Kumar N, Ramakrishnan V, Johnson GV, Southern S. Endoscopically-assisted excision of scapular osteochondroma. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70:394-396.

18. Majo J, et al. Elastofibroma dorsi as a cause of shoulder pain or snapping scapula. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;388:200-204.

19. Boinet M. Crépitation rude du scapulum. Bull Soc Imperiale Chir. 1867;8:458.

20. Kuhn JE, Plancher KD, Hawkins RJ. Symptomatic scapulothoracic crepitus and bursitis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:267-273.

21. Kuhn JE The scapulothoracic articulation: anatomy, biomechanics, pathophysiology, and management. Ianotti JP, Williams GE, editors. Disorders of the Shoulder: Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1999:817-845.

22. Mauclaire. Craquements sous-capsulaires pathologiques traits par l’interposition musculaire interscapulo-thoracique. Bull Mem Soc Chir Paris. 1904;30:164-168.

23. Arntz CT, Matsen FAIII. Partial scapulectomy for disabling scapulothoracic snapping. Orthop Trans. 1990;14:252.

24. McCluskey GMIII, Bigliani LU. Surgical management of refractory scapulothoracic bursitis. Orthop Trans. 1991;15:801.

25. McCluskey GMIII, Bigliani LU. Scapulothoracic disorders. In: Andrew JR, Wilk KE, editors. The Athlete’s Shoulder. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1994:305-316.

26. Nicholson GP, Duckworth MA. Scapulothoracic bursectomy for snapping scapula syndrome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:80-85.

27. Pavlik A, Ang K, Coghlan J, Bell S. Arthroscopic treatment of painful snapping of the scapula by using a new superior portal. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:608-612.

28. Sisto DJ, Jobe FW. The operative treatment of scapulothoracic bursitis in professional pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14:192-194.

29. Manske RC, Reiman MP, Stovak ML. Nonoperative and operative management of snapping scapula. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1554-1564.

30. Pearse EO, Bruguera J, Massoud SN, et al. Arthroscopic management of the painful snapping scapula. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:755-761.

31. Milch H, Burman M. Snapping scapula and humerus varus. Arch Surg. 1933;26:570-588.

32. Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG Muscle Testing and Function 81, 4th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1993.

33. Mozes G, Bickels J, Ovadia D, Dekel S. The use of three-dimensional computed tomography in evaluating snapping scapula syndrome. Orthopedics. 1999;22:1029-1033.

34. O’Holleran JD, Millett PJ, Warner JP. Arthoscopic management of scapulothoracic disorders. In: Miller MD, Cole BJ, editors. Textbook of Arthroscopy. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2004:277-285.

35. Wood VE, Verska JM. The snapping scapula in association with the thoracic outlet syndrome. Arch Surg. 1989;124:1335-1337.

36. McCluskey GM, Bigliani LU. Partial scapulectomy for disabling scapulothoracic snapping. Orthop Trans. 1990;14:252-253.

37. Galinat BJ Endoscopic scapuloplasty: a minimum two-year follow-up. Orthop Trans, 21; 1997:134.

38. Chan B, Chakrabarti AJ, Bell SN. An alternative portal for scapulothoracic arthroscopy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:235-238.