Synonyms/Description

Many different types of uterine sarcoma, including but not limited to carcinosarcoma, adenosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, and endometrial stromal sarcoma

Etiology

Uterine sarcomas are rare tumors of mesenchymal origin, representing approximately 5% of all uterine malignancies.

They are classified into three groups according to their source:

1. Mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumors, which include carcinosarcomas. These were previously termed malignant mixed Müllerian tumors (MMMTs) and adenosarcomas.

2. Smooth muscle tumors, which are leiomyosarcomas

3. Endometrial stromal tumors, which include endometrial stromal sarcoma and high-grade undifferentiated sarcoma

Carcinosarcoma is the most common, accounting for 50% of all uterine sarcomas. It is typically diagnosed in the sixth decade and often presents with postmenopausal bleeding. The presentation and risk factors are similar to endometrial adenocarcinoma. It is an aggressive tumor with extrauterine spread to lymph nodes or beyond found in 30% of patients at initial diagnosis.

Adenosarcoma is a less aggressive tumor than carcinosarcoma. It tends to be smaller and confined to the uterus at presentation and has a more favorable prognosis.

Leiomyosarcoma is the second most common uterine sarcoma, occurs mostly in the fifth decade of life, and accounts for almost 40% of cases. These tumors are not thought to arise from existing myomas. They generally present with the same symptoms attributed to enlarging fibroids and rapid growth of the uterus.

Endometrial stromal sarcomas represent approximately 10% of uterine sarcomas and typically present with vaginal bleeding and pelvic pain in women 40 to 55 years of age.

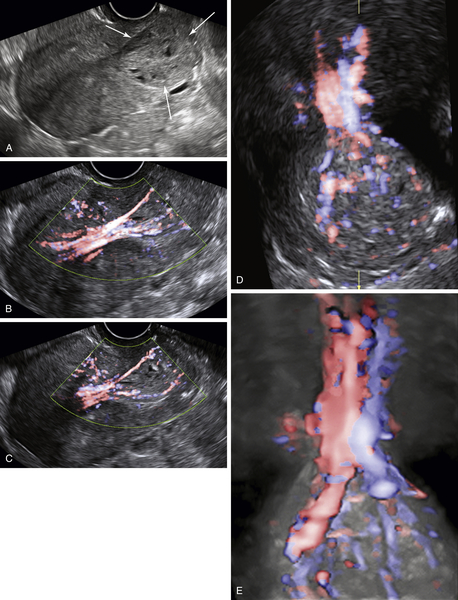

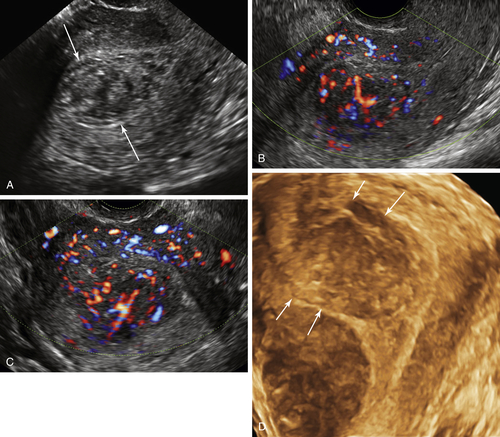

Ultrasound Findings

Uterine sarcomas usually present as large uterine masses that may be difficult to distinguish from fibroids. They can be polypoid with cystic spaces and ill-defined borders. They often involve the endometrium, at least in part, and may prolapse or extend through the endocervical canal. This type may be mistaken for a submucosal degenerating fibroid or an endometrial polyp. The appearance of a vascular, intraluminal mass can also mimic endometrial adenocarcinoma. Doppler usually shows abundant blood flow as is common in malignancies. The diagnosis of a sarcoma may be suspected if the mass is irregular with disorganized cystic areas and especially if the mass is rapidly growing and very vascular. Leiomyosarcomas are typically difficult to distinguish from highly vascular benign leiomyomas by imaging alone.

Clinical Aspects and Recommendations

Five-year overall survival for patients with stage 1 to 2 uterine carcinosarcoma is 44% to 74%. The survival for women with stage 1 to 2 leiomyosarcoma is 52% to 85%.

Endometrial stromal sarcoma has the best prognosis, with a 90% 5-year survival rate in women with stage I disease. Survival is poor in patients with stage III to IV disease for all types of sarcomas.

The treatment for uterine sarcomas depends on the type of tumor and the extent of disease. Uterine sarcomas are relatively rare and should be managed at specialized centers because treatments are typically multimodal and evolving. Recurrence rates are relatively high compared with other types of gynecologic malignancies.