Chapter 120 SAMe (S-Adenosylmethionine)

Introduction

Introduction

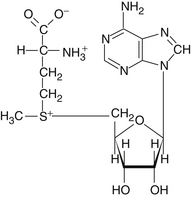

S-Adenosylmethionine (SAMe) is an important physiologic agent formed in the body through combination of the essential amino acid methionine with adenosyl triphosphate (ATP) (Figure 120-1). SAMe was discovered in Italy in 1952. Not surprisingly, most of the research on SAMe has been conducted in the country of its discovery.

Because SAMe is manufactured from methionine, one would think that dietary sources of methionine would provide the same benefits as SAMe. However, high doses of methionine have not been shown to raise levels of SAMe, nor do they provide the same pharmacologic activity as SAMe. High doses of methionine are associated with some degree of toxicity.1

Clinical Indications

Clinical Indications

Depression

SAMe is necessary in the manufacture of important brain compounds, such as neurotransmitters and phospholipids like phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylserine. Adding SAMe to the diet of depressed patients raises levels of serotonin, dopamine, and phosphatidylserine and improves binding of neurotransmitters to receptor sites, resulting in increased serotonin and dopamine activity and better brain-cell membrane fluidity, leading to significant clinical improvement.2–4

The antidepressant effects of folic acid (see Chapter 142) are mild compared with the effects noted in clinical trials of SAMe. On the basis of results from a number of clinical studies, it appears that SAMe is perhaps the most effective natural antidepressant (although a strong argument could be made for the extract of St. John’s wort standardized to contain 0.3% hypericin).5–11

Although most of the early studies used injectable SAMe, the later studies have used an oral dose of 400 mg four times daily (1600 mg total) and have demonstrated that SAMe is just as effective given orally as when it is given intravenously.4,10–15 That is not surprising, because there are no significant differences in the pharmacokinetic parameters of SAMe 1000 mg administered orally or intravenously.16

Several studies have compared SAMe with tricyclic antidepressants. Before the rise of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclics were the mainstay pharmaceutical treatment for depression. A 2002 review concluded that “at doses of 200 to 1600 mg/day, SAMe is superior to placebo and is as effective as tricyclic antidepressants in alleviating depression, although some individuals may require higher doses.”10 The reviewers found six of eight placebo-controlled studies, featuring anywhere from 40 to 100 participants, demonstrating that SAMe was superior to placebo; moreover, six of eight comparison studies showed that SAMe was just as effective as tricyclic antidepressants. These studies have shown that SAMe is better tolerated than the tricyclics and has a quicker onset of antidepressant action.11

In one study comparing SAMe with desipramine, in addition to determining the clinical response, the blood level of SAMe was determined in both groups. At the end of the 4-week trial, 62% of the patients treated with SAMe and 50% of those treated with desipramine had significantly improved. Regardless of the type of treatment, patients with a 50% decrease in scores on the Hamilton Depression Scale showed a significant rise in plasma SAMe concentration. These results suggest that one of the ways in which tricyclic antidepressant agents exert their antidepressant effects is by raising SAMe levels.17

In two separate double-blind studies, SAMe was given orally (1600 mg daily) or intramuscularly (400 mg daily) and compared with 150 mg of imipramine given orally daily. In both studies, the results of SAMe and imipramine treatment did not differ significantly for any efficacy measure. However, significantly fewer adverse events were observed in the patients treated with SAMe. The researchers concluded that the antidepressant efficacy of 1600 mg SAMe orally and 400 mg SAMe intramuscularly is comparable with that of 150 mg of imipramine but that SAMe is significantly better tolerated.18

In a double-blind, randomized clinical trial lasting 6 weeks, 73 depressed patients who were unresponsive to SSRI medications alone were given 800 mg of SAMe or placebo twice daily along with their SSRIs.19 The response and remission rates according to the Hamilton Depression Scale were higher for patients treated with adjunctive SAMe (36.1% and 25.8%, respectively) than adjunctive placebo (17.6% versus 11.7%, respectively). These results indicate that SAMe can be used safely with SSRIs and may have a synergistic effect.

In a study on 20 HIV-seropositive individuals with depression, SAMe as a sole antidepressant medication showed significant effect. There was a significant reduction in acute depressive symptomatology, reaching the defined clinical treatment response threshold of a greater than 50% reduction in symptom scores. The researchers also noted that SAMe had a rapid effect as early as after only 1 week, with progressive decreases in symptom scores throughout the study.20

SAMe has also been shown to produce significant effects in other conditions associated with depression, as during the postpartum period and in drug rehabilitation. SAMe’s benefits in these conditions are probably due to a combination of its effects on brain chemistry and liver function (discussed later). In the study in postpartum depression, the administration of SAMe (1600 mg/day) was associated with significantly better mood scores compared with placebo.21 In another study, SAMe (1200 mg/day) was shown to significantly reduce psychological distress (chiefly anxiety and depression) in the detoxification and rehabilitation of opiate abusers.22

SAMe may also be helpful in managing the symptomatology of schizophrenia. In one double-blind study, 18 patients with chronic schizophrenia were randomly assigned to receive either SAMe (800 mg) or placebo for 8 weeks. Results indicated some reduction in aggressive behavior and improved quality of life following SAMe administration. Female patients showed improvement of depressive symptoms, whereas male patients showed no change compared with placebo. Blood dopamine levels increased in women, but decreased in men receiving SAMe. Clinical improvement did not correlate with serum SAMe levels. Two patients receiving SAMe exhibited some exacerbation of irritability; therefore, it should be used with caution in these patients.23

Detailed clinical evaluations using electroencephalography, event-related potentials, and low-resolution brain electromagnetic tomography have clearly indicated a central nervous system antidepressant action of SAMe.18

Osteoarthritis

SAMe has also demonstrated impressive results in the treatment of osteoarthritis.24–26 A deficiency of SAMe in the joint tissue, just like a deficiency of glucosamine, leads to loss of the gel-like nature and shock-absorbing qualities of cartilage. As a result, osteoarthritis can develop.

In vitro studies have shown that SAMe exerts a number of effects that appear to be highly relevant in the treatment of osteoarthritis. First, the agent has been shown to be very important in the manufacture of cartilage components.27 This effect has been demonstrated very well in humans. In one double-blind study conducted in Germany, the 14 patients with osteoarthritis of the hands who were given SAMe showed greater cartilage formation on magnetic resonance imaging.28 These results indicate that SAMe is capable of improving the structure and function of cartilage in joints affected by osteoarthritis. Second, SAMe has shown some mild pain-relieving and anti-inflammatory effects in animal studies.1 All of these effects combine to produce exceptional clinical benefits.

In double-blind trials, SAMe has demonstrated similar reductions in pain scores and clinical symptoms to those produced by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen, indomethacin, naproxen, nabumetone, celecoxib, and piroxicam. In one double-blind study, SAMe was compared with ibuprofen.29 The 36 subjects with osteoarthritis of the knee, hip, and/or spine received a daily oral dose of 1200 mg of SAMe or 1200 mg of ibuprofen for 4 weeks. Morning stiffness, pain at rest, pain on motion, crepitation (crackling noise upon movement of a joint), swelling, and limitation of motion of the affected joints were assessed before and after treatment. The total score obtained by evaluating all the individual clinical parameters improved to the same extent in patients treated with SAMe and in those treated with ibuprofen. In two other studies, SAMe was actually shown to produce slightly better results.30,31

SAMe has also been compared with naproxen (Naprosyn). In one double-blind study, 20 patients with osteoarthritis of the knee were given either SAMe or naproxen for 6 weeks.32 During the first week, SAMe was administered at a dose of 400 mg three times daily and afterward at a dose of 400 mg twice daily, whereas the dose of naproxen during the first week was 250 mg three times daily and subsequently 250 mg twice daily. During the first 2 weeks, the patients were allowed to take the drug paracetamol as an additional analgesic if the pain was severe. The patients were examined at the beginning of the study and after 2, 4, and 6 weeks. The parameters tested were pain, crepitation, joint swelling, circumference of joint, extent of motility, and 10-meter walking time. At the end of the sixth week, no statistically significant difference between the two patient groups was found; both groups exhibited a marked improvement on all parameters.

Another double-blind study compared SAMe with both naproxen and placebo in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip, knee, spine, and hand. The study involved 33 rheumatologic and orthopedic medical centers and a total of 734 subjects. SAMe administered orally at a dose of 1200 mg daily was shown to exert the same analgesic (pain-relieving) activity as naproxen at a dose of 750 mg daily. However, SAMe was found to be significantly more effective than naproxen, both in terms of physicians’ and patients’ judgments and in terms of the number of patients with side effects. In fact, SAMe was better tolerated than placebo. A total of 10 patients in the SAMe group and 13 in the placebo group withdrew from the study because of intolerance to the drug.33 Other double-blind studies have shown SAMe to offer pain-relieving and antiinflammatory benefits similar to those of drugs like indomethacin and piroxicam while also being generally much better tolerated than these potent NSAIDs.34,35

Perhaps the most meaningful study of SAMe in the treatment of osteoarthritis was a long-term multicenter open 2-year trial involving 97 patients with osteoarthritis of the knee, hip, and spine.36 The patients received 600 mg of SAMe daily (equivalent to three tablets of 200 mg each) for the first 2 weeks and thereafter 400 mg daily (equivalent to two tablets of 200 mg each) until the end of the 24th month of treatment. Separate evaluations were made for osteoarthritis of the knee, hip, cervical spine, and dorsal-lumbar spine. The severity of the clinical symptoms (morning stiffness, pain at rest, and pain on movement) was assessed with scoring before the start of the treatment, at the end of the first and second weeks of treatment, and then monthly until the end of the 24-month period. SAMe showed good clinical effectiveness and was well tolerated. Improvement in the clinical symptoms during therapy with SAMe was already evident after the first weeks and continued to the end of treatment. Nonspecific side effects occurred in 20 patients, but in no case did therapy have to be discontinued. Most side effects disappeared during the course of therapy. Moreover, during the last 6 months of treatment, no adverse effect was recorded. Detailed laboratory tests carried out at the start and after 6, 12, 18, and 24 months of treatment showed no pathologic changes. SAMe administration also improved the depressive feelings often associated with osteoarthritis.

One study compared the efficacy and tolerability of SAMe (1200 mg/day) and nabumetone (Relafene, 1000 mg/day) in 134 patients with osteoarthritis of the knee for 8 weeks.37 An analysis of changes in pain intensity between weeks 0 and 8 found that both SAMe and nabumetone effectively reduced pain intensity from baseline in each group and that the degree of decrease in pain intensity was not significantly different between the groups. The patients’ global assessments of disease status, physician’s global assessment of response to therapy, and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) index scores were not significantly different between the groups.

A randomized double-blind crossover study, comparing SAMe (1200 mg) with celecoxib (Celebrex 200 mg) for 16 weeks to reduce pain associated with osteoarthritis of the knee in 56 subjects showed that SAMe has a slower onset of action but is as effective as celecoxib in the management of symptoms of knee osteoarthritis.38

Finally, in the largest study, 20,641 patients with osteoarthritis of the knee, hip, and spine and also with osteoarthritic polyarthritis of the fingers were studied over 8 weeks.39 The patients were given 400 mg of SAMe three times daily for the first week, 400 mg twice daily for the second week, and 200 mg twice daily from the third week onward. No additional analgesic or antiinflammatory treatment was allowed. The efficacy of SAMe was comparable with results achieved with NSAIDs. Efficacy was described as very good or good in 71% of cases, moderate in 21%, and poor in 9%; tolerance of the agent was assessed as very good or good in 87%, moderate in 8%, and poor in 5%.

Fibromyalgia

SAMe has been shown in four double-blind clinical studies to produce excellent benefits in patients suffering from fibromyalgia.40–43 In two of the studies, injectable SAMe (200 mg daily) was used. During treatment, subjects demonstrated significant reductions in the number of trigger points and painful areas as well as improvements in mood.40,41

In one of the studies, oral SAMe (800 mg/day) was compared with a placebo for 6 weeks in 44 patients with fibromyalgia.42 Tender-point score, muscle strength, disease activity, subjective symptoms, mood parameters, and side effects were evaluated. Patients given SAMe demonstrated improvements in clinical disease activity, pain experienced during the last week, fatigue, morning stiffness, and mood; however, the tender-point score and muscle strength did not differ in the two treatment groups. SAMe was without side effects.

In one of the studies, SAMe was compared with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation—a popular treatment for fibromyalgia—in 30 patients with this disorder.43 Patients receiving SAMe (200 mg by injection and 400 mg/day orally) experienced significantly greater clinical benefit as shown by a decreased number of tender points, diminished subjective feelings of pain and fatigue, and improved mood. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation offered little benefit for most symptoms, whereas SAMe was deemed “effective in relieving the signs and symptoms of primary fibromyalgia.”43

Liver Disorders

SAMe has been shown to be beneficial in several liver disorders, including cirrhosis, Gilbert’s syndrome, and oral contraceptive–induced liver damage. Its benefits are related to its function as the major methyl donor in the liver as well as its lipotropic activity. One of the leading contributors to impaired liver function is diminished bile flow, or cholestasis. SAMe is beneficial for a variety of liver disorders because of its ability to promote bile flow and relieve cholestasis.44,45

One of the key functions of SAMe in the liver is the inactivation of estrogens. Clinical studies have shown that SAMe is useful in protecting the liver from damage and improving liver function in conditions associated with estrogen excess—namely, oral contraceptive use, pregnancy, and premenstrual syndrome.46–48

Another key indication for the use of SAMe is in the treatment of Gilbert’s syndrome, a common disorder characterized by a chronically elevated serum bilirubin level (1.2 to 3.0 mg/dL). Previously considered rare, this disorder is now known to affect as many as 5% of the general population. The condition is usually without symptoms, although some patients complain of loss of appetite, malaise, and fatigue (typical symptoms of impaired liver function). SAMe at a dosage of 400 mg three times daily has resulted in a significant decrease in serum bilirubin in patients with Gilbert’s syndrome.49

In addition to these relatively minor disturbances in liver function, SAMe offers benefits in the treatment of more severe liver disorders, including cirrhosis. Its effect in cirrhosis appears to be due to an ability to overcome the SAMe depletion characterized by the disorder. Because SAMe is involved in so many liver processes, the depletion of levels of SAMe within the liver has serious consequences. Supplementation with SAMe in patients with liver cirrhosis not only improves bile flow and clinical signs and symptoms but also promotes membrane function and increases levels of glutathione.50–53 Glutathione assumes a critical role in detoxification as well as in the defense against a variety of injurious agents by combining directly with these toxic substances to eventually form water-soluble compounds. Because many of the toxic compounds are lipid- (fat-) soluble, conversion to water-soluble compounds results in more efficient excretion via the kidneys. When higher levels of toxic compounds are present or liver function is impaired, higher glutathione levels are required.

One of the greatest risks of chronic liver diseases such as chronic hepatitis is liver cancer. Supplementation with SAMe appears to be strongly indicated in patients with such diseases in the attempt to reduce the risk for liver cancer. Animal studies have shown a significant protective effect of supplemental SAMe against liver cancer in animals exposed to liver carcinogens.54

Dosage

Dosage

• Depression: 400 to 1600 mg daily. Because SAMe can cause nausea and gastrointestinal disturbances in some people, it is recommended that it be started at a dosage of 200 mg twice daily for the first day, increased to 400 mg twice daily on day 3, and finally raised to the full dosage of 800 mg twice daily after 10 days if needed.

• Osteoarthritis: The dosage is best started out as above for depression. After 21 days at a dosage of 1600 mg daily, the maintenance dosage is reduced to 200 mg twice a day.

• Fibromyalgia: 200 to 400 mg two times a day.

Interactions and Contraindications

Interactions and Contraindications

SAMe functions very closely with vitamin B12, folic acid, vitamin B6, and choline in methylation reactions. Because of SAMe’s effects on the liver, it may enhance the elimination of various drugs from the body.56 The clinical significance of this effect has not been fully determined.

It has been cautioned that SAMe should be avoided in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Animal studies indicate that excessive methylation is associated with Parkinson’s disease, and SAMe excess has caused Parkinson’s disease–like effects in animal studies.57 In addition, both animal and human studies indicate that increased methylation can cause the depletion of dopamine and block the effects of L-dopa.53,58,59 This line of research is contradicted, however, by preliminary evidence that SAMe may improve the emotional depression and impaired mental function often associated with this disorder.50 Nonetheless, it is recommended that patients with Parkinson’s disease avoid supplementing with SAMe until more is known.

1. Stramentinoli G. pharmacologic aspects of S-adenosylmethionine: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Am J Med. 1987;83:35–42.

2. Bottiglieri T., Hyland K., Reynolds E.H. The clinical potential of ademetionine (S-adenosylmethionine) in neurological disorders. Drugs. 1994;48:137–152.

3. Fava M., Rosenbaum J.F., MacLaughlin R., et al. Neuroendocrine effects of S-adenosyl-L-methionine, a novel putative antidepressant. J Psychiatr Res. 1990;24:177–184.

4. Papakostas G.I. Evidence for S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM-e) for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 5):18–22.

5. Bressa G.M. S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) as antidepressant: meta-analysis of clinical studies. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1994;154:7–14.

6. Janicak P.G., Lipinski J., Davis J.M., et al. Parenteral S-adenosyl-methionine (SAMe) in depression: literature review and preliminary data. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1989;25:238–242.

7. Friedel H.A., Goa K.L., Benfield P. S-adenosyl-L-methionine: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic potential in liver dysfunction and affective disorders in relation to its physiological role in cell metabolism. Drugs. 1989;38:389–416.

8. Carney M.W., Toone B.K., Reynolds E.H. S-adenosylmethionine and affective disorder. Am J Med. 1987;83:104–106.

9. Vahora S.A., Malek-Ahmadi P. S-adenosylmethionine in the treatment of depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1988;12:139–141.

10. Mischoulon D. Fava M.Role of S-adenosyl-L-methionine in the treatment of depression: a review of the evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002 Nov;76(5):1158S–1161S.

11. Delle Chiaie R., Pancheri P., Scapicchio P. Efficacy and tolerability of oral and intramuscular S-adenosyl-L-methionine 1,4-butanedisulfonate (SAMe) in the treatment of major depression: comparison with imipramine in 2 multicenter studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002 Nov;76(5):1172S–1176S.

12. Kagan B.L., Sultzer D.L., Rosenlicht N., et al. Oral S-adenosylmethionine in depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:591–595.

13. Rosenbaum J.F., Fava M., Falk W.E., et al. An open-label pilot study of oral S-adenosylmethionine in major depression: interim results. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:189–194.

14. De Vanna M., Rigamonti R. Oral S-adenosyl-L-methionine in depression. Curr Ther Res. 1992;52:478–485.

15. Salmaggi P., Bressa G.M., Nicchia G., et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of S-adenosyl-L-methionine in depressed postmenopausal women. Psychother Psychosom. 1993;59:34–40.

16. Yang J., He Y., Du Y.X., et al. Pharmacokinetic properties of S-adenosylmethionine after oral and intravenous administration of its tosylate disulfate salt: a multiple-dose, open-label, parallel-group study in healthy Chinese volunteers. Clin Ther. 2009 Feb;31(2):311–320.

17. Bell K.M., Potkin S.G., Carreon D., et al. S-adenosylmethionine blood levels in major depression: changes with drug treatment. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1994;154:15–18.

18. Delle Chiaie R., Pancheri P., Scapicchio P. Efficacy and tolerability of oral and intramuscular S-adenosyl-L-methionine 1,4-butanedisulfonate (SAMe) in the treatment of major depression: comparison with imipramine in 2 multicenter studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:1172S–1176S.

19. Papakostas G.I., Mischoulon D., Shyu I., et al. S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe) augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors for antidepressant nonresponders with major depressive disorder: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(8):942–948.

20. Shippy R.A., Mendez D., Jones K., et al. S-adenosylmethionine (SAM-e) for the treatment of depression in people living with HIV/AIDS. BMC Psychiatry. 2004 Nov 11;4:38.

21. Cerutti R., Sichel M.P., Perin M., et al. Psychological distress during puerperium: a novel therapeutic approach using S-adenosylmethionine. Curr Ther Res. 1993;53:707–717.

22. Lo Russo A., Monaco M., Pani A., et al. Efficacy of S-adenosyl-L-methionine in relieving psychological distress associated with detoxification in opiate abusers. Curr Ther Res. 1994;55:905–913.

23. Strous R.D., Ritsner M.S., Adler S., et al. Improvement of aggressive behavior and quality of life impairment following S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM-e) augmentation in schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009 Jan;19(1):14–22.

24. Soeken K.L., Lee W.L., Bausell R.B., et al. Safety and efficacy of S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) for osteoarthritis. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:425–430.

25. Schumacher H.R., Jr. Osteoarthritis: the clinical picture, pathogenesis, and management with studies on a new therapeutic agent, S-adenosylmethionine. Am J Med. 1987;83:1–4.

26. Montrone F., Fumagalli M., Sarzi Puttini P., et al. Double-blind study of S-adenosyl-methionine versus placebo in hip and knee arthrosis. Clin Rheumatol. 1985;4:484–485.

27. Harmand M.F., Vilamitjana J., Maloche E., et al. Effects of S-adenosymethionine on human articular chondrocyte differentiation: an in vitro study. Am J Med. 1987;83:48–54.

28. Konig H., Stahl H., Sieper J., et al. Magnetic resonance tomography of finger polyarthritis: morphology and cartilage signals after ademetionine therapy. Aktuelle Radiol. 1995;5:36–40.

29. Muller-Fassbender H. Double-blind clinical trial of S-adenosylmethionine versus ibuprofen in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Am J Med. 1987;83:81–83.

30. Glorioso S., Todesco S., Mazzi A., et al. Double-blind multicentre study of the activity of S-adenosylmethionine in hip and knee osteoarthritis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1985;5:39–49.

31. Marcolongo R., Giordano N., Colombo B., et al. Double-blind multicentre study of the activity of S-adenosyl-methionine in hip and knee osteoarthritis. Curr Ther Res. 1985;37:82–94.

32. Domljan Z., Vrhovac B., Durrigl T., et al. A double-blind trial of ademetionine vs naproxen in activated gonarthrosis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1989;27:329–333.

33. Caruso I., Pietrogrande V. Italian double-blind multicenter study comparing S-adenosylmethionine, naproxen, and placebo in the treatment of degenerative joint disease. Am J Med. 1987;83:66–71.

34. Vetter G. Double-blind comparative clinical trial with S-adenosylmethionine and indomethacin in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Am J Med. 1987;83:78–80.

35. Maccagno A., Di Giorgio E.E., Caston O.L., et al. Double-blind controlled clinical trial of oral S-adenosylmethionine versus piroxicam in knee osteoarthritis. Am J Med. 1987;83:72–77.

36. Konig B.A. Long-term (two years) clinical trial with S-adenosylmethionine for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Am J Med. 1987;83:89–94.

37. Kim J., Lee E.Y., Koh E.M., et al. Comparative clinical trial of S-adenosylmethionine versus nabumetone for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: an 8-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, Phase IV study in Korean patients. Clin Ther. 2009 Dec;31(12):2860–2872.

38. Najm W.I., Reinsch S., Hoehler F., et al. Harvey PW.S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe) versus celecoxib for the treatment of osteoarthritis symptoms: a double-blind cross-over trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004;26(5):6.

39. Berger R., Nowak H. A new medical approach to the treatment of osteoarthritis: report of an open phase IV study with ademetionine (Gumbaral). Am J Med. 1987;83:84–88.

40. Tavoni A., Vitali C., Bombardieri S., et al. Evaluation of S-adenosylmethionine in primary fibromyalgia: a double-blind crossover study. Am J Med. 1987;83:107–110.

41. Volkmann H., Norregaard J., Jacobsen S., et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study of intravenous S-adenosyl-L-methionine in patients with fibromyalgia. Scand J Rheumatol. 1997;26:206–211.

42. Jacobsen S., Danneskiold-Samsoe B., Andersen R.B. Oral S-adenosylmethionine in primary fibromyalgia: double-blind clinical evaluation. Scand J Rheumatol. 1991;20:294–302.

43. Di Benedetto P., Iona L.G., Zidarich V. Clinical evaluation of S-adenosyl-L-methionine versus transcutaneous nerve stimulation in primary fibromyalgia. Curr Ther Res. 1993;53:222–229.

44. Frezza M., Surrenti C., Manzillo G., et al. Oral S-adenosylmethionine in the symptomatic treatment of intrahepatic cholestasis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:211–215.

45. Avila M.A., Garcia-Trevijano E.R., Martinez-Chantar M.L., et al. S-Adenosylmethionine revisited: its essential role in the regulation of liver function. Alcohol. 2002;27:163–167.

46. Di Padova C., Tritapepe R., Di Padova F., et al. S-adenosyl-L-methionine antagonizes oral contraceptive-induced bile cholesterol supersaturation in healthy women: preliminary report of a controlled randomized trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79:941–944.

47. Nicastri P.L., Diaferia A., Tartagni M., et al. A randomised placebo-controlled trial of ursodeoxycholic acid and S-adenosylmethionine in the treatment of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:1205–1207.

48. Frezza M., Pozzato G., Pison G., et al. S-adenosylmethionine counteracts oral contraceptive hepatotoxicity in women. Am J Med Sci. 1987;293:234–238.

49. Bombardieri G., Milani A., Bernardi L., et al. Effects of S-adenosyl-methionine (SAMe) in the treatment of Gilbert’s syndrome. Curr Ther Res. 1985;37:580–585.

50. Angelico M., Gandin C., Nistri A., et al. Oral S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) administration enhances bile salt conjugation with taurine in patients with liver cirrhosis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1994;54:459–464.

51. Kakimoto H., Kawata S., Imai Y., et al. Changes in lipid composition of erythrocyte membranes with administration of S-adenosyl-L-methionine in chronic liver disease. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1992;27:508–513.

52. Loguercio C., Nardi G., Argenzio F., et al. Effect of S-adenosyl-L-methionine administration on red blood cell cysteine and glutathione levels in alcoholic patients with and without liver disease. Alcohol. 1994;29:597–604.

53. Mato J.M., Camara J., Fernandez de Paz J., et al. S-adenosylmethionine in alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter clinical trial. J Hepatol. 1999;30:1081–1089.

54. Pascale R.M., Marras V., Simile M.M., et al. Chemoprevention of rat liver carcinogenesis by S-adenosyl-L-methionine: a long-term study. Cancer Res. 1992;52:4979–4986.

55. Gatto G., Caleri D., Michelacci S., et al. Analgesizing effect of a methyl donor (S-adenosylmethionine) in migraine: an open clinical trial. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1986;6:15–17.

56. Reicks M., Hathcock J.N. Effects of methionine and other sulfur compounds on drug conjugations. Pharmacol Ther. 1988;37:67–79.

57. Cheng H., Gomes-Trolin C., Aquilonius S.M., et al. Levels of L-methionine S-adenosyltransferase activity in erythrocytes and concentrations of S-adenosylmethionine and S-adenosylhomocysteine in whole blood of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 1997;145:580–585.

58. Charlton C.G., Crowell B., Jr. Parkinson’s disease-like effects of S-adenosyl-L-methionine effects of L-dopa. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1992;43:423–431.

59. Di Rocco A., Rogers J.D., Brown R., et al. S-Adenosyl-methionine improves depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease in an open-label clinical trial. Mov Disord. 2000;15:1225–1229.