CHAPTER 115 Sacroiliac Joint Rehabilitation and Manipulation

INTRODUCTION

The path taken to diagnose sacroiliac joint (SIJ) pain may not be a straight or clearly marked one. Although several studies point to a battery of tests for diagnosing SIJ problems, a standardized protocol has yet to be devised. As a result, the treatment of SIJ pain can be difficult. Similar to many musculoskeletal problems, treatment success with SIJ pain is often varied due to cofactors surrounding each patient. Accordingly, one uniform approach is not likely. Instead, a combination of treatment options that can be applied to varied patient classifications will be more effective. A sacroiliac joint belt with manual therapy may be very successful in one individual and merely provoke pain in another. The treatment must be tailored to the individual. The patient’s history regarding the circumstances around when the pain began is often paramount in selecting treatment and management. For the sake of consistency in this chapter, the authors will use the term posterior pelvic pain to be inclusive of pain related to the sacroiliac joint, but not exclusive to only intra-articular pain. Posterior pelvic pain includes reference to periarticular pain including muscle, fascia, and ligaments around the sacroiliac joint.

TREATMENT

Manual therapy

Manual therapies can be used separately or in combination with other pain-reducing modalities. In fact, evidence suggests that decreasing musculoskeletal pain may be one of the most important roles for manual therapy.1,2 In several studies, manual therapy has been shown to be superior to traditional modalities in reducing pain, sometimes even in the absence of change to objective variables, such as range of motion.3,4 Accordingly, the authors believe it is important to consider manual therapy as a tool to reduce pain, and to pair it with rehabilitative strategies, such as stabilization exercise, to restore function. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of studies substantiating this position; however, the authors’ collective experiences suggest that this form of treatment can be beneficial.

Therapeutic rehabilitation

There is a vast array of physical therapy approaches to treatment of posterior pelvic pain. One theory proposed by Sahrmann5,6 seeks resolution in symptoms by correcting muscle and joint dysfunction based on specific muscle(s) activation. This theory relies on conscious correction of motor patterns and avoiding activities that promote pain and/or poor movement patterns. A person treated for acute posterior pelvic pain utilizing this treatment method might be instructed to use crutches so as to not develop or enhance a poor gait pattern. In contrast, other theories of treatment develop recommendations based on gross movement patterns. An example is McKenzie’s theory of systematic treatment for spine dysfunctions.7 Treatment applied is based on specific movement patterns related to spine pathology. A spine stabilization program attempts to combine therapeutic exercises based on deficiencies in spine, abdominal, and hip muscle length and strength. This method also relies on conscious overriding of poor movement patterns. At times, deciding what is acceptable and unacceptable pain while performing exercises in the latter two treatment groups can be difficult for the patient. Another theory proposed by Gray8 recommends using multiple joint movement patterns to improve function but relies on unconscious retraining of movement. The movement patterns are directed either into the restrictive range of movement or away from the restriction. Movement pattern direction is determined by the patient’s pain tolerance. If moving towards the restrictive movement is too painful, applying joint motion, loading, and unloading in the movement pattern and plane tolerated is suggested. As the motion and pain improves, the direction and combination of planes of motion advances. Gray’s approach also incorporates the pelvic floor musculature, an area often omitted from traditional programs. The pelvic floor and diaphragm are thought to play an important role in core or trunk stability. This theory is somewhat ahead of current research validation, but is a growing area of interest in some centers. In general, Gray’s approach to treatment focuses on developing a therapeutic exercise program to resemble the patient’s functional activity requirements.

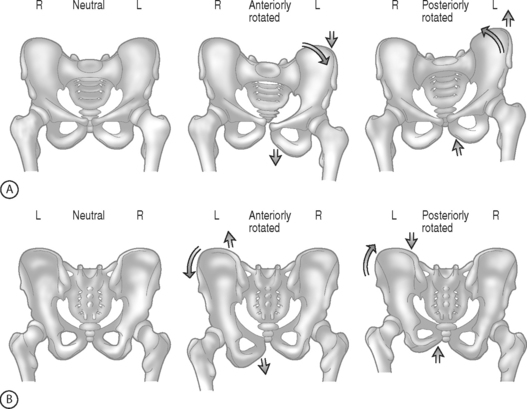

Regardless of what method or combination of methods are used, rehabilitation for posterior pelvic pain must incorporate spine, hip, and pelvic structures and mechanics. Pool-Goudzwaard et al.9 and Vleeming et al.10 have described the importance of the muscle and connective tissue network that assists in the stability of the lumbopelvis and specifically the sacroiliac joint. They have demonstrated through dissection and biomechanical modeling that there is a direct relationship between the tensioning of the dorsal sacral ligament, sacrotuberous ligament, erector spinae muscles, hamstrings, and the movement of the SIJ.11 Additionally, the iliopsoas commonly works in a shortened position. This shortened position can enhance the development of an anteriorly rotated ilium (Fig. 115.1). Hamstring strengthening cannot be accomplished until the iliopsoas is restored to activating in a biomechanically efficient length. An anterior pelvic tilt forces the hamstring to work in a lengthened position. The hamstring is a key muscle in providing stability to the sacroiliac joint because of its direct attachment and/or fascial connections to the sacrotuberous ligament. Other muscles commonly found to be working in a shortened position include the rectus femoris, tensor fascia lata, adductors, quadratus lumborum, latissimus dorsi,12 and obturator internus. Achieving appropriate muscle flexibility may take weeks to achieve. The authors advocate utilizing a stretching program that encompasses all three planes of motion. As muscle length is restored and stiffness reduced, strengthening of muscles inhibited by the biomechanical deficit can be completed. Neuromuscular re-education and facilitation techniques are helpful with this process. Closed kinetic chain strengthening should be attempted first and can then be incorporated into the lumbopelvic stabilization exercises. As trunk strengthening improves, adding multiplanar strengthening exercises will facilitate return to functional activities. Muscles commonly found to be weak include the gluteus medius, gluteus maximus, lower abdominals, and hamstrings. These are merely suggestions that are based on the authors’ experience with respect to muscle patterns of movement proposed by Janda,13,14 and Norris.15,16 As Norris points out,16 these ‘muscle imbalance categorization can usefully assist the astute practitioner, they are not cast in stone.’ Each patient presents with a unique set of circumstances with regards to pain, muscle imbalance, and joint mechanics. The healthcare practitioner must take the patient’s individual set of problems, strengths, and goals into account when creating a treatment program.

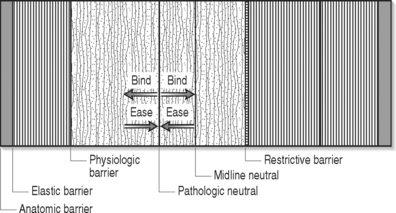

Manipulation is commonly used to treat posterior pelvic pain related to the sacroiliac joint. Manipulation is a term that may have several definitions. For the sake of discussion in this chapter it will refer to manipulation as treatment that involves manual techniques that restore joint motion. An explanation of the barrier systems utilized to direct manual therapy is useful in understanding the different approaches of manual medicine. The absolute end range of motion within any single plane of motion is referred to as the anatomic barrier (Fig. 115.2). Motion that goes beyond this barrier results in fracture, dislocation, or ligamentous or tendon tear. Within the total range of motion of any joint there are different limits to active and passive range. Active range of motion is limited by a physiological barrier. This barrier is maintained by muscle, ligament, tendon, and capsule. With passive range of motion, increased motion is obtained to the elastic barrier. Again, this barrier is maintained by the previously mentioned soft tissue structures, but at their endpoint of elasticity or length. A restrictive barrier forms as a result of a biomechanical dysfunction. This barrier reduces the active range of motion and increases the space between available active range of motion and the elastic barrier. A restrictive barrier is created by skin, fascia, long and short muscles, ligament, tendon, and joint capsules. Regardless of the specific type of manipulation used, the goal is to move the restrictive barrier back toward the elastic barrier. There are many techniques that can be used to achieve this goal. The choice of technique is examiner dependent as well as dependent on what is thought to be causing the restriction(s).

Fig. 115.2 Illustration of barriers enhances understanding of the basis of the theory of manipulation.

There are many different techniques used to manipulate a joint to restore motion. Strain–counterstrain developed by Jones,17 an osteopathic physician, is a technique where the healthcare provider palpates for tender points within the restricted area. There are many theories regarding the location and significance of trigger points. Overlap in location is noted in the trigger points identified as Travell’s myofascial trigger points,18 Chapman’s reflex points,17 and acupuncture. Strain–counterstrain utilizes any or all of these identified trigger points to assess and treat the patient. The treatment consists of the examiner monitoring the trigger point while passively positioning the patient until the pain is relieved at the trigger point. Once this position of relief is determined, it is maintained for 90 seconds. The examiner then passively repositions the patient back to a neutral position. In general, the position of comfort is found in the direction away from the restrictive barrier. Pain relief is thought to occur by reducing the inappropriate proprioceptor activity. The inappropriate strain reflex in the painful muscle is inhibited by stretching (counterstrain) the antagonist muscle. This technique is especially helpful to reduce pain related to muscle tone when more active intervention is painful.

Muscle energy techniques were first described in osteopathic medicine in the 1960s by physicians T.J. Ruddy and Fred Mitchell, Snr.19 More recently, further expansion has been made by Karel Lewitt and Vladimir Janda. The basic principle involves the healthcare provider passively placing a joint in the position away form the restrictive barrier and the patient then performs an isometric contraction against the force of the healthcare provider. After completing the contraction, the healthcare provider stretches the soft tissues to allow the joint to move through the restrictive barrier. This method of treatment applies both passive positioning and muscle activation to move through a barrier. Lewitt20 has modified this approach and termed it postisometric relaxation (PIR). Importantly, PIR emphasizes a light contraction of the muscle and does not engage the stretch reflex. The procedure is very gentle and usually very comfortable. The doctor identifies the muscle that is overactive and takes the muscle to pathological barrier of functional resistance. The doctor will then ask the patient to lightly contract the muscle being lengthened for approximately 3–5 seconds. After the light contraction, the patient is asked to relax. With relaxation the doctor lengthens the muscle to a comfortable, improved length. This is typically repeated 3–4 times.

Active release therapy (ART) is a (patented) technique used to treat soft tissue problems involving muscles, tendons, ligaments, and nerves. ART is a method of soft tissue mobilization which lengthens hypertrophied or shortened muscles, tendons, ligaments, and connective tissue.21 Preliminary studies with ART have produced encouraging results with a variety of musculoskeletal conditions.22 Once the practitioner has identified the area of tension or adhesion of tissue, a firm manual contact is applied with the thumb or finger to the area of soft tissue pathology. The practitioner will then shorten the muscle or tissues being treated. While maintaining specific opposition on the area of identified tension or fibrosis, the practitioner will ask the patient to lengthen the muscle and release and/or break up the restrictive tissue. This often promotes better inter- and intramuscular gliding and can improve muscle activation. In cases of posterior pelvic pain, ART can help restore movement for the pelvis by addressing dorsal sacral ligament, sacrotuberous ligament, and hamstrings. This may also be applied to conditions of nerve entrapment by muscles or fascia. Common entrapment sites for posterior pelvic pain include sciatic, gluteal, or lateral femoral cutaneous nerve locations.

High-velocity low-amplitude (HVLA) manipulation is the technique often associated with the term ‘manipulation.’ Evidence and international guidelines identifying the efficacy of this type of manipulation for low back pain have flourished since 1986.23–27 This type of manipulation is the form most commonly used by chiropractors. With this technique the patient is moved passively to the restrictive barrier and the examiner then applies an extrinsic force (quick thrust) to move the joint through the restrictive barrier.28 Optimally, one joint is mobilized at a time and restoration of motion at that joint is achieved. The thrust is thought to gap the joint and the gapping is thought to cause the audible pop. While the effects of thrust manipulation remain poorly understood, evidence suggests that the impact is largely a central neurological mechanism.29 Zhu et al.30 demonstrated that decreased pain response after lumbar manipulation was associated with abnormal somatosensory-evoked potentials from paraspinal patients with low back pain. Lehman and McGill,31 in their preliminary investigation, suggested that manipulation could attenuate the muscular response that directly inhibits pain. Suter et al.32 studied the effects of SIJ manipulation on the inhibitory effect of the quadriceps muscle in knee joint pathology. They showed an interaction between manipulation and inhibition of voluntary activity produced by pain.

Joint mobilization is a general term coined by physical therapy which is similar in theory to HVLA with one exception. While the goal of HVLA is to move through the restrictive barrier, joint mobilization involves applying grades of pressure to improve motion up to the restrictive barrier but not through it. Lewitt,20 a Czech neurologist, describes several approaches to this type of mobilization for the SIJ. This can include engaging the barrier of resistance and holding or rhythmically springing the barrier.

The risk surrounding HVLA for the lower back is often perceived high although it is actually relatively low. Shelkelle33 estimated the serious complication rate for lumbar manipulation at 1 in 100 million manipulations. Haldeman34 revealed that 16 of the 26 cases reported to have complications between 1911 and 1989 had been performed with anesthesia. Therefore, manipulation under anesthesia should be applied with caution.

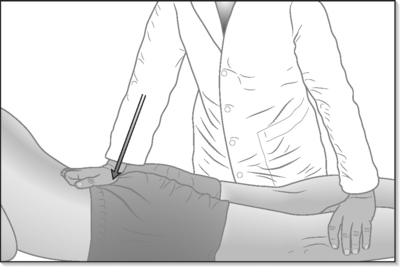

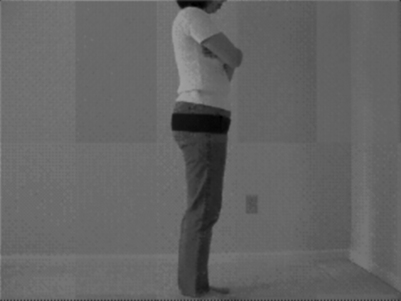

Manipulation used for posterior pelvic pain may include any one or combination of the aforementioned techniques. Choosing which to use is usually determined by the practitioner’s skill, experience, and training. When addressing asymmetries in the pelvis, a technique using muscle activation (ART, muscle energy, contract–relax) is often helpful. Utilizing the muscle activation is helpful as the muscles around the hip and pelvis are large, powerful, and have different functions depending on positioning of the hip. Repositioning can continue until all planes of motion have been addressed. The natural follow-up to the muscle activation treatment is a muscle flexibility and strengthening home exercise program that mimics the manipulation. For example, after a muscle energy technique is applied to reverse a unilateral anterior iliac rotation, the patient should be educated how to perform an iliopsoas stretch encompassing three planes (frontal, sagittal, transverse) of motion (Fig. 115.3). The home exercise program can then facilitate maintaining the improvements made with manipulation. A HVLA treatment might be chosen when muscle activation techniques have failed to provide consistent improvement. There are several sacral thrust maneuvers (Fig. 115.4). In general, a thrust is applied to the sacrum, but is directed in the plane of restriction. The theory is that the applied force will allow a return of improved motion to the joint. Again, the home exercise program should be created to enhance the benefits of the manipulation. For example, the patient who benefits from a sacral thrust performed distally, thereby freeing a unilateral posterior iliac rotation, will likely benefit from a hamstring stretch as part of the home exercise program.

Adjunct therapy

SIJ belts are often offered as part of the treatment plan for posterior pelvic pain. The belts are used to provide compression to the pelvis (Fig. 115.5). This is particularly helpful in patients with hypermobility at the joint and/or significant muscle weakness. In addition to compression, proprioceptive feedback to the gluteal muscles can assist with neuromuscular re-education. Vleeming35 reported that SIJ belts applied to cadaver models reduced SIJ rotation by 30%. In the clinical setting, Vleeming demonstrated that by stabilizing the ilium, the belts assist with improving hip flexion active range of motion. The healthcare provider must insure that the patient is able to apply the belt appropriately. The SIJ belt should be secured posteriorly across the sacral base and anteriorly, inferior to the anterior superior iliac spines. SIJ belts can dramatically reduce symptoms during walking and standing activities. However, patients with significant pain and weakness may find the belt helpful in reducing symptoms when worn during sedentary activities as well. Recommendations regarding the use of SIJ belts should be individualized, based on the patient’s history and activity goals.

Other adjunct treatment considerations include orthotics and shoe modifications. If a leg length discrepancy is noted on physical examination, the examiner should determine if it is a functional or anatomical discrepancy. A shoe lift to correct a functional leg length discrepancy can be helpful in the acute setting to manage pain with weight bearing or ambulating. After the pain with weight bearing has improved, the healthcare provider should determine if the shoe lift should continue to be used. The goal should be to reduce or resolve the functional leg length discrepancy via the therapeutic rehabilitation program. There is some recent evidence that footwear modifications can have systemic effects.36 An inappropriate shoe lift can promote adaptive muscle imbalances, which may initially be asymptomatic. Over time, these changes in force transmission and absorption across the pelvis may become symptomatic. Anatomical leg length discrepancies should be determined as early in treatment as possible so that the appropriate modifications can be completed.

SIJ injections can be used as an adjunct to a physical therapy program if the patient’s progress plateaus or the program cannot be advanced because of pain provocation. The injections can also be used diagnostically if done under fluoroscopic guidance. Maigne37 reported 18.5% of 54 patients diagnosed with SIJ pain responded to double SIJ block under fluoroscopic guidance. This study did not control for other treatments given and therefore accurately reports only what an injection alone can improve. Slipman et al. analyzed a cohort of 31 patients who underwent therapeutic SIJ intra-articular injection.38 A minimum follow-up interval of 12 months was used. They found statistically and clinically significant improvement in visual analog scale (VAS) ratings and Oswestry scores. The average VAS rating reduction was in excess of 30 (out of 100). Luukkainen and colleagues39 reported improved visual analog scale and pain index scores at 1 month after a periarticular SIJ steroid injection. This study included 13 patients who received steroid compared to 11 who received saline and lidocaine. The injections were performed by palpation over the painful site at the SIJ region and no control was made for other treatments. In another study, 10 of 12 patients who underwent SIJ steroid injection via MRI guidance reported an improved VAS at 3-month follow-up.40 Again, no control or standardization of other conservative treatment was completed. Though study numbers at this time are small, there is evidence to suggest that SIJ injections should be used as an adjunct treatment in pain management.

Recently, studies have reported improvement in chronic SIJ pain treated with radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Ferrante and associates41 reported a 50% reduction in VAS reports for at least 6 months in 33 patients. The authors noted that a positive response to treatment was associated with an atraumatic inciting event, reduction in the area of referred pain on the pain diagram, normalization of SIJ pain provocation tests, and reduction in opioid use with radiofrequency denervations. Although the Ferrante study suggests that RFA was achieved, this conclusion is suspect. The technique used simply entailed placing three probes into the joint. It is more likely that osseous and/or cartilaginous injury resulted from the local heating effect rather than a denervation procedure. Yin and colleagues42 reported a retrospective review of 14 patients who underwent sensory stimulation-guided sacral lateral branch radiofrequency neurotomy for treatment of chronic SIJ pain. Sixty-four percent experienced consistent relief in pain with a 50% reduction in visual integer pain score 6 months after the procedure. Included in these successful outcomes were 36% who had complete relief in their symptoms. In another study, Cohen43 reported choosing radiofrequency ablation candidates for chronic SIJ pain by performing diagnostic blocks at the levels innervating the SIJ (L4–5 dorsal rami and S1–3 lateral branches). Thirteen of 18 patients reported significant relief with nine reporting greater than 50% relief at follow-up. These nine underwent radiofrequency ablation of all branches previously blocked. Eight out of nine (89%) obtained 50% or greater pain relief that continued at 9-month follow-up.

Using the same basic theories behind radiofrequency ablation, Calvillo et al.44 reported two cases of chronic SIJ pain treated by implanting a neuroprosthesis at the third sacral root. The authors reported that the patients continued to use analgesics before and after the procedure, but the patients reported that their activities of daily living were ‘more tolerable.’ These procedures appear to have some promise in the treatment of chronic SIJ pain. More studies are needed to determine long-term outcomes and determine which patients might be good candidates.

SIJ hypermobility unresponsive to the above-outlined program is a difficult problem. SIJ arthrodesis45 and percutaneous fixation46 have been utilized for instability. Long-term outcome studies thus far have not been completed and it is unknown what happens to surrounding articulations with the lumbar spine, contralateral SIJ, and hip years after SIJ fusion. Other therapies such as prolotherapy have been proposed as an invasive but less permanent option. Prolotherapy is described as the provocation of the laying down of an increased volume of normal collagen material in ligament, tendon, or fascia in order to restore function of the tissue at a specific site.47 Provocation is achieved by provoking an inflammatory response at the location. A wide variety of agents have been used to provoke local inflammation, including high-concentration glucose solutions to phenol alcohol. Often it is a combination of agents. Though the safety48 and clinical outcomes have been reported,49 no prospective, controlled studies exist to date on the specific use of prolotherapy and SIJ dysfunction.

TREATMENT SCENARIOS

Recovery phase (3 days to 8 weeks)

Once pain has been controlled and the injured area has been rested, correction of the functional biomechanical deficit and tissue overload complex50 becomes the focus of rehabilitation. Balancing lower extremity muscle length and strength is important because of direct and indirect force transmission across the ilium and sacrum. Muscle length must be restored to facilitate appropriate joint mechanics at the hip, SIJ, and spine. Again, in this phase of treatment muscle energy and active release techniques are often successful in reducing pain as well as restoring functional motion. In cases where the above techniques have been partially successful or unsuccessful at relieving pain and improving motion, HVLA or mobilization techniques may be helpful. The home exercise program should include self-mobilization exercises to insure carry-over of the manually applied treatment. Once the mobilization has been successful the focus of treatment should turn to maintaining muscle length while improving muscle strength and endurance. Maintaining muscle flexibility with exercises that address all three planes of motion will also reinforce improvements made with the manual techniques. Medications during this time should include nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications. These medications should be initiated with consistent daily dosage and then weaned as needed and eventually discontinued. If sleep is a problem due to pain, taking advantage of the sedating side effect of muscle relaxers may be helpful by prescribing them for nighttime use. Narcotics and medicines such as tramadol, may be useful but in a limited setting. The goal is to minimize their use. If improvements are plateauing or limited by pain, a therapeutic SIJ steroid injection may be useful with regard to treatment, and a positive response makes one feel more comfortable about the diagnosis. The authors recommend these injections be performed with fluoroscopic guidance to insure accuracy of placement and reduce complications caused by misplacement. The patient should be made aware that the injection is an adjunct treatment utilized to facilitate the progress of physical therapy. As pain improves, the exercise prescription should advance. Muscle flexibility and strengthening exercises should progress to weight bearing, utilizing all three planes of motion. As this improves, the home program should start to incorporate or mimic functional, exercise, or sport-specific activities. Return to unrestricted activities or exercise occurs once the patient is pain free, range of motion and strength have been restored, the patient has demonstrated good technique with activities, and has returned to or initiated an aerobic training program. Education with regards to the importance of a maintenance program should be completed prior to discharge.

Treatment for a nontraumatic injury (1–3 days)

The treatment course of a nontraumatic injury should progress similarly to that of a traumatic injury. Initially, the etiology of the problem may not be clear or identified and, as a result, a period of trial and error can often ensue. For example, if the patient began with a segmental restriction at L5–S1 and continues to have posterior pelvic pain that is responding only in part to therapy directed at the SIJ, the restriction at L5–S1 may need to be addressed before further progress can be made. Again, the L5–S1 restriction can be treated with a variety of therapeutic interventions including joint mobilization, manipulation, muscle energy, and contract–relax. Care must be taken to resolve neurogenic pain symptoms. This can be addressed via medications, neuromobilization, and injections. Recurrent or continuous neurogenic pain can inhibit progress being made with muscle flexibility and strength. Clearing hip dysfunction can also be a key factor in progressing a treatment program for posterior pelvic pain. Godges and colleagues51 described this scenario in a case report of a 74-year-old female with posterior pelvic pain thought to be related to the SIJ. They presented a detailed description of successive physical examinations and physical therapy sessions. The iliac and sacral restrictions resolved within a few sessions of combined manual techniques, neuromuscular re-education, and muscle flexibility and strengthening exercises. Despite these improvements, the patient continued to have pain and activity limitations. Further progress was made once the range of motion (ROM) of the hip on the symptomatic side improved to becoming more symmetrical with the ROM on the asymptomatic side. Adjunct treatments should be instituted in the nontraumatic patient in similar fashion as the traumatic patient. Again, care should be taken to look for areas of dysfunction away from the SIJ if the patient requires prolonged use of medications, or repeated injections. Repetitive manipulation to the SIJ can have long-term side effects of joint hypermobility. Freeing restrictions at the spine and pelvis can be vital in making SIJ manual therapy successful.

Special populations

Pregnancy

Studies have suggested that between 50–80% of women suffer from low back pain and/or posterior pelvic pain (LBP/PPP) during pregnancy.52–61 Ostgaard and Roos-Hansson62 demonstrated that during pregnancy pain is more commonly attributed to posterior pelvic pain and postpartum is more commonly occurring from dysfunctions within the lumbar spine.63 Of 119 women with pain for more than 2 months postpartum, 27% were thought to have posterior pelvic pain, 18% lumbar spine pain, 39% posterior pelvic and lumbar pain, and in 16% no pain could be provoked on physical examination. Understanding these different etiologies can better direct treatment plans.

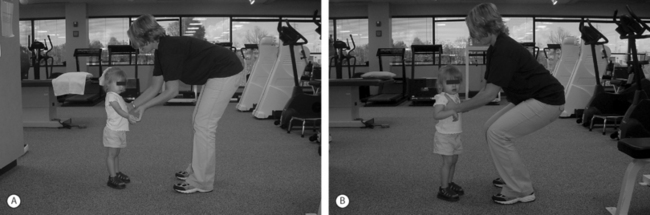

Treatment for posterior pelvic pain during pregnancy should progress similar to that in the nonpregnant population. Exceptions include the care that should be taken in both examining and applying manual therapy treatments in the pregnant population. Ligamentous laxity promotes joint hypermobility. Overzealous ROM or manipulation can provoke both further pain and dysfunction in this population. On the other hand, SIJ belts can be exceptionally helpful in reducing pain by providing proprioceptive feedback and compression to the gluteal muscles that help provide joint stability. Stabilization exercises should be promoted with care and not all activities should be performed in the supine position. The home exercise program will need to be adjusted as the abdominal girth increases. Instead of lengthening the lever arm with strengthening exercises, it may need to be reduced to adjust for biomechanical inefficiencies. Education is key with regards to activities of daily living, ergonomics of lifting (Fig. 115.6), and position choices during labor when possible. For example, laboring in a side-lying position with the hip in full flexion, abduction and external rotation may further provoke posterior pelvic pain that began during pregnancy.

Noren et al.,64 in their study using an education and physiotherapy intervention, calculated a cost savings of US$53 000 for reducing LBP/PPP in pregnancy in 30 women. Education for LBP/PPP in pregnancy has also been studied and proven helpful in reducing the common chronicity seen with these patients.35,61,62,65 These studies all suggest early advice for best results.

The authors’ preliminary studies also suggest an important role for assessing and treating the muscles and ligaments of the spine and pelvis in pregnancy-related LBP/PPP.68 While several exercise-directed interventions have been proposed for soft tissue dysfunction in pregnancy-related LBP/PPP,67–72 very little has been studied regarding manual soft tissue intervention.73,74

The procedures the authors utilize most are the muscle energy and ART. While both address muscles, ligaments, tendons, and connective tissue, they are clinically different from traditional massage. PIR is a method of soft tissue mobilization which lengthens shortened muscles that are hypertonic or contain trigger points.20

A few studies on LBP in pregnancy have included manipulation and mobilization in their treatment protocols with encouraging preliminary results.60,75–77 McIntyre and Broadhurst75 and Daly and Rapoza76 showed a 90% success rate in reducing pain in women with pregnancy-related LBP by using thrust manipulation for sacroiliac dysfunction. Berg et al.60 found 70% improvement in women with severe LBP in pregnancy who received specific SIJ mobilization. In a retrospective review, Daikow provided evidence of an 84% success rate in reducing back pain during pregnancy and back labor through manipulation.76 The goal with these procedures is to reduce tension or restricted movement in the pain-generating structures, thereby decreasing the patient’s pain and assisting self-care strategies of activity modification, stretching, and exercise.

1 Anderson R, Meeker WC, Wirick BE, et al. A meta-analysis of clinical trials of spinal manipulation. J Manip Physiol Ther. 1992;15:181-194.

2 Nilsson N, Christensen HW, Hartvigsen J. Lasting changes in passive range motion after spinal manipulation: a randomized, blind, controlled trial. J Manip Phys Ther. 1996;19(3):165-168.

3 Koes BW, Bouter LM, Van Mameren H, et al. The effectiveness of manual therapy, physiotherapy, and treatment by the general practitioner for nonspecific back and neck complaints: A randomized clinical trial. Spine. 1992;17:28-35.

4 Koes BW, Bouter LM, Van Mameren H, et al. Randomized clinical trial of manipulative therapy and physiotherapy for persistent back and neck complaints: Results of one year follow up. Br Med J. 1992;304:601-605.

5 Sahrmann SA. Diagnosis and treatment of movement impairment syndromes. Chicago: Mosby, 2001.

6 Maluf KS, Sahrmann SA, Van Dillen LR. Use of a classification system to guide nonsurgical management of a patient with chronic low back pain. Phys Ther. 2000;80(11):1097-1111.

7 McKenzie RA. Mechanical diagnosis and therapy for low back pain. In: Physical therapy of low back pain. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1987.

8 Gray GW. Total body functional profile. In: Gray GW, editor. Total body functional profile. Adrian, Michigan: Wynn Marketing, Inc and Gary Gray Physical Therapy Clinic, Inc; 2001:7-9.

9 Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Bleeming A, Stoeckart R, et al. Insufficient lumbopelvic stability: a clinical, anatomical and biomechanical approach to ‘a-specific’ low back pain. Man Ther. 1998;3(1):12-20.

10 Vleeming A, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Stoeckart R, et al. The posterior layer of the thorocolumbar fascia. Spine. 1995;20:753-758.

11 Vleeming A, Hammudoghlu D, Stoeckart R, et al. The function of the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament. Spine. 1996;21:556-562.

12 Geraci MC. Rehabilitation of the hip and pelvis. In: Kibler WB, Herring SA, Press JM, editors. Functional rehabilitation of sports and musculoskeletal medicine. Maryland: Aspen Publishers; 1998:216-243.

13 Janda V. Muscle weakness and inhibition in back pain syndromes. In: Grieve G, editor. Modern manual therapy of the vertebral column. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1986.

14 Janda V. Muscle spasm – a proposed procedure for the differential diagnosis. Manual Med. 1991;1001:6136-6139.

15 Norris CM. Spine stabilization. Muscle imbalance and the low back. Physiotherapy. 1995;81(3):127-138.

16 Norris CM. The designation debate. J Bodywork Movement Ther. 2000;4(4):225-241.

17 Jones LH. Strain and counterstrain. In: Jones LH, editor. Strain and counterstrain. The Indianapolis, IN: American Academy of Osteopathy; 1981:11-14.

18 Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial pain and dysfunction, Vol 2 . Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1992.

19 Chaitow L. An introduction to muscle energy techniques. In: Chaitow L, editor. Muscle energy techniques. 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2001:1-17.

20 Lewitt K. Manipulative therapy in rehabilitation of the motor system. London: Butterworths, 1985.

21 Leahy PM, Active Release soft tissue management system. Course Manual 1999.

22 Schiottz-Christensen BMV, Azad S, Selstad D, et al. The role of active release manual therapy for upper extremity overuse syndromes – a preliminary report. J Occup Rehabil. 1999;9:210.

23 Flynn TW, Fritz JM, Wainner RS, et al. The audible pop is not necessary for successful spinal high-velocity thrust manipulation in individuals with low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(7):1057-1060.

24 Aure OF, Nilsen JH, Vasseljen O. Manual therapy and exercise therapy in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial with 1 year follow up. Spine. 2003;28(6):525-531.

25 Van den Hout JH, Vlaeyen JW, Houben RM, et al. The effects of failure feedback and pain-related fear on pain report, pain tolerance, and pain avoidance in chronic low back pain patients. Pain. 2001;92(1–2):247-257.

26 Manniche C, Jordan A. Evidence based medicine. Spine. 2001;26(7):842-844.

27 Royal College of General Practitioners. Clinical guidelines for the management of acute low back pain. Royal College of General Practitioners, London, 1999. www.rcgp.org.uk.

28 Mein EA. Overview of techniques and system approaches to manipulation. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 1996;7(4):731-747.

29 Haldeman S. Neurologic effects of the adjustment. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2000;23:112-114.

30 Zhu Y, Starr A, Seffinger MA, et al. Paraspinal muscle evoked cerebral potentials in patients with unilateral low back pain. Spine. 1993;18:1096-1102.

31 Lehman GJ, McGill SM. Effects of a mechanical pain stimulus on erector spinae activity before and after a spinal manipulation in patients with back pain: a preliminary investigation. J Manip Phys Ther. 2001;24(6):402-406.

32 Suter E, Herzog W, Bray R. Conservative lower back treatment reduces inhibition in knee-extensor muscles: A randomized controlled trial. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2000;23:76-80.

33 Shelkelle PG, Chassin MR, Surwitz EL, et al. Spinal manipulation for low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:590-598.

34 Haldeman S, Rubenstein SM. Cauda equina syndrome in patients undergoing manipulation of the lumbar spine. Spine. 1992;17:1469-1473.

35 Vleeming A, Buyruk HM, Stoeckart R, et al. Towards an integrated therapy for peripartum pelvic instability: A study of the biomechanical effects of pelvic belts. Am J Obs Gynecol. 1992;166:1243-1247.

36 Mundermann A, Nigg BM, Humble RN, et al. Foot orthotics affect lower extremity kinematics and kinetics during running. Clin Biomech. 2003;18(3):254-262.

37 Maigne JY, Aivaliklis A, Pfefer F. Results of sacroiliac joint double block and value of sacroiliac pain provocation tests in 54 patients with low back pain. Spine. 1996;21:1889-1892.

38 Slipman CW, Lipetz JS, Vresilovic EJ, et al. Fluoroscopically guided therapeutic sacroiliac joint injections for sacroiliac joint syndrome. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80(6):425-432.

39 Luukkainen RK, Wennerstrand PV, Kautiainen HH, et al. Efficacy of periarticular corticosteroid treatment of the sacroiliac joint in non-spondyloarthropathic patients with chronic low back pain in the region of the sacroiliac joint. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20:52-54.

40 Pereira PL, Gunaydin I, Duda SH, et al. MR-guided steroid injection of the sacroiliac joints: preliminary results. J de Radiolgie. 2000;81:223-226.

41 Ferrante FM, King LF, Roche EA, et al. Radiofrequency sacroiliac joint denervations for sacroiliac syndrome. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001;26(6):592-593.

42 Yin W, Willard F, Carreiro J, et al. Sensory stimulation-guided sacroiliac joint radiofrequency neurotomy: techniques based on neuroanatomy of the dorsal sacral plexus. Spine. 2003;28(20):2419-2425.

43 Cohen SP, Abdi S. Lateral branch blocks as treatment for sacroiliac joint pain: A pilot study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003;28(2):113-119.

44 Calvillo O, Esses SI, Ponder C, et al. Spine. 1998;23(9):1069-1072.

45 Keating JG, Avillar MD, Price M. Sacroiliac joint arthrodesis in selected patients with low back pain. In: Vleeming A, Mooney V, Dorman T, et al, editors. Movement, stability and low back pain. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:573-586.

46 Lippitt AB. Percutaneous fixation of the sacroiliac joint. In: Vleeming A, Mooney V, Dorman T, et al, editors. Movement, stability and low back pain. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:587-594.

47 Dorman TA. Pelvic mechanics and prolotherapy. In: Vleeming A, Mooney V, Dorman T, et al, editors. Movement, stability and low back pain. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:501-522.

48 Dorman TA. Prolotherapy: A survey. J Orthop Med. 1993;15:2.

49 Ongley MJ, Klein RG, Dorman TA, et al. A new approach to the treatment of chronic low back pain. Lancet. 1987;2:143-146.

50 Herring SA. Rehabilitation of muscle injuries. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990;22:455.

51 Godges JJ, Varnum DR, Sand KM. Impairment-based examination of disability management of an elderly woman with sacroiliac region pain. Phys Ther. 2002;82(8):812-821.

52 Fast A, Ducommun EJ, Friedmann LW, et al. Low-back pain in pregnancy. Spine. 1987;11:368-371.

53 MacArthur C, Knox EG, Crawford JS. Epidural anaesthesia and long term backache after childbirth. Br Med J. 1990;301:9-12.

54 Ostgaard HC, Karlsson K. Prevalence of back pain in pregnancy. Spine. 1991;16:549-551.

55 Heckman JD. Musculoskeletal considerations in pregnancy. J Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76A:1720-1730.

56 Endresen EH. Pelvic pain and low back pain in pregnant women – an epidemiological study. Scand J Rheumatol. 1995;24:135-141.

57 Kristiansson P, Von Schoultz B. Back pain during pregnancy: A prospective study. Spine. 1996;21:702-709.

58 Bullock JE, Bullock MI. The relationship of low back pain to postural changes during pregnancy. Austr J Physiother. 1987;33:10-17.

59 Stapleton DB, Kristiansson P. The prevalence of recalled low back pain during and after pregnancy: A South Australian population survey. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;42:482-485.

60 Berg G, Moller-Nielsen J, Linden U, et al. Low back pain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:71-75.

61 Orvieto R, Ben-Rafael Z, Gelernter I, et al. Low-back pain of pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1994;73:209-214.

62 Ostgaard HC, Roos-Hansson E. Back pain in relation to pregnancy. Spine. 1997;22:2945-2950.

63 Nilsson-Wikmar L, Harms-Ringdahl K, Pilo C, et al. Back pain in women postpartum is not a unitary concept. Physiother Res Int. 1999;4(3):201-213.

64 Noren L, Johansson G, Ostgaard HC. Lumbar back and posterior pelvic pain during pregnancy: A 3-year follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:267-271.

65 Mantle MJ, Currey HLF. Backache in pregnancy II: Prophylactic influences of back care classes. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1981;20:227-232.

66 Skaggs CD, Ducar D, Prather H. Musculoskeletal intervention for low back and pelvic pain in pregnancy. 2003.

67 Suputtitada A, Chaisayan P. Effect of the ‘sitting pelvic tilt exercise’ during the third trimester in primigravides on back pain. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002;85:S170-S178.

68 Duffy S. Chronic pelvic pain: defining the scope of the problem. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;74(Suppl 1):S3-S7.

69 Mens JMA, Stam HJ. Diagonal trunk muscle exercises in peripartum pelvic pain: A randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2000;80:1164-1173.

70 Stuge BM. The efficacy of a specific stabilization exercise program in the treatment of patients with peripartum pelvic pain after pregnancy. A randomized controlled trial. Montreal: 2001.

71 Rath J, Mielscarski E, Waldman R. Low back pain during pregnancy: Helping patients take control. J Musculoskel Med. 2000:223-232.

72 Kihlstrand M, Nilsson S, Axelsson O. Water-gymnastics reduced the intensity of back/low back pain in pregnancy women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78:180-185.

73 Requejo SM, Kulig K, Landel R, et al. The use of a modified classification system in the treatment of low back pain during pregnancy: A case report. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32:318-326.

74 Vleeming A, de Vries HJ, Mens JM, et al. Possible role of the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament in women with peripartum pelvic pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81(5):430-436.

75 McIntyre IN, Broadhurst NA. Effective treatment of low back pain in pregnancy. 1996;9(Suppl 2):S65-S67.

76 Daly JM, Rapoza PA. Sacroiliac subluxation: a common, treatable cause of low back pain in pregnancy. Family Pract Res J. 1991;22:149-159.

77 Fung BKP, Ho ESC. Low back pain of women during pregnancy in the mountainous district of central Taiwan. Chin Med J. 1993;51:103-106.