Chapter 11 Sacroiliac Joint Block and Neuroablation

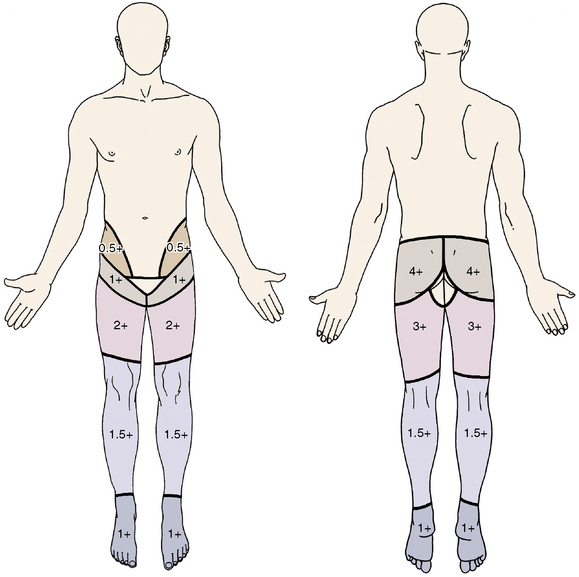

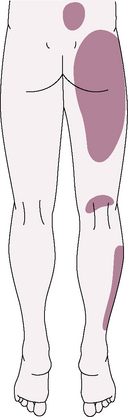

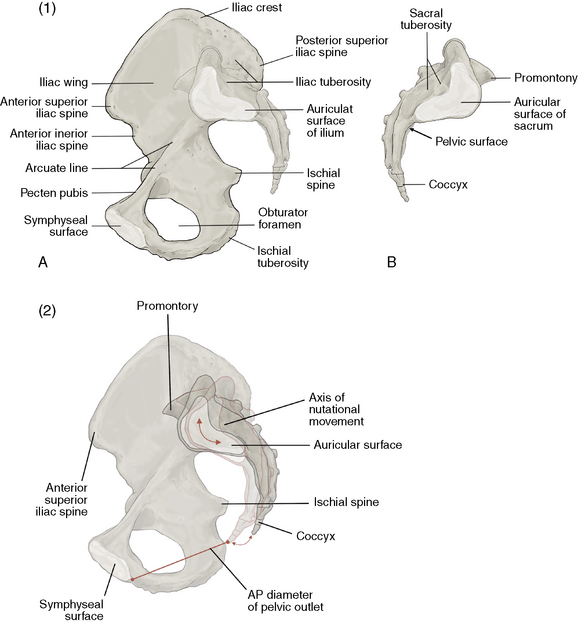

The sacroiliac joint (SIJ) is the largest axial joint in the body with an average surface area of 17.5 cm2 [1]. It is a large, auricular-shaped, diarthrodial synovial joint. However, only the anterior third of the interface between the sacrum and ilium is a true synovial joint; the rest of the junction is comprised of an intricate set of ligamentous connections. If the joints become painful, they may cause pain in the low back, buttocks, abdomen, groin or legs (Figs. 11-1 and 11-2).

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction

Dreyfuss and colleagues [2] have shown that the pain referral pattern in asymptomatic volunteers consists of the following areas:

Pain in the region of the SIJ with possible radiation to the groin, medial buttocks, and posterior thigh

Pain in the region of the SIJ with possible radiation to the groin, medial buttocks, and posterior thigh An ostensibly morphologically normal joint without demonstrable pathognomonic radiographic abnormalities

An ostensibly morphologically normal joint without demonstrable pathognomonic radiographic abnormalitiesThe prevalence of SIJ pain in carefully screened patients with low back pain (LBP) is in the range of 15% to 25%. 39% of patients with SIJ dysfunction were also diagnosed [3] with an associated spinal disorder. Of these spinal disorders complicated by SIJ dysfunction, the most common are as follows:

The following factors predispose an individual to SIJ dysfunction:

The average mechanical threshold of the SIJ nociceptive unit is shown in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1 Average Mechanical Threshold of Sacroiliac Joint and Other Nociceptive Units

| Nociceptive Unit | Average Mechanical Threshold (g) |

|---|---|

| Sacroiliac joint | 70 |

| Lumbar facet joint | 6 |

| Anterior lumbar disc | 241 |

The local anesthetic and cortisone can help break a pain cycle, possibly facilitating a rehabilitative exercise program.

The local anesthetic and cortisone can help break a pain cycle, possibly facilitating a rehabilitative exercise program.The evidence for the effectiveness of SIJ block and denervation as diagnostic and therapeutic methods for SIJ dysfunction is shown in Table 11.2.

Table 11.2 Level of Evidence for Intra-articular Injection and Neurotomy

| Intra-articular injection: | |

| Diagnostic method | Moderate evidence for diagnosis of pain from the sacroiliac joint (SIJ) |

| Therapeutic method | Moderate evidence for short-term relief (<3 months) Limited evidence for long-term relief |

| Radiofrequency neurotomy | Indeterminate evidence for managing SIJ pain |

Indications

No evidence of lumbar pain generators (if indicated, this can be confirmed through negative results of zygapophys-eal joint block and discography)

No evidence of lumbar pain generators (if indicated, this can be confirmed through negative results of zygapophys-eal joint block and discography) At least 75% relief with controlled, dual, fluoroscopically guided, contrast-enhanced intra-articular SIJ injections

At least 75% relief with controlled, dual, fluoroscopically guided, contrast-enhanced intra-articular SIJ injectionsSeveral major diagnostic tests are used to confirm a diagnosis of intra-articular SIJ pain; they are described in Table 11.3 and Box 11.1, and shown in Figures 11-3 through 11-5.

Table 11.3 Sensitivity and Specificity of Major Diagnostic Tests Used to Identify Patients with Intra-articular Sacroiliac Joint Pain

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Sacroiliac joint pain | ++++ | + |

| Groin pain | + | +++ |

| Buttock pain | ++++ | + |

| Indication of posterior superior iliac spine as pain source | ++++ | ++ |

| Abnormal sitting posture | + | ++++ |

| Pain lessens with: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs Exercise Manipulation |

++ ++ +++ |

++ ++++ ++++ |

| Gillet test | ++ | +++ |

| Patrick test | +++ | + |

| Gaenslen test | +++ | ++ |

| Sacral sulcus tenderness | ++++ | + |

| Midline sacral thrust | +++ | ++ |

| Bone scan | ++ | ++++ |

| Computed tomography | +++ | +++ |

+, 0-25%; ++, 26%-50%; +++, 51%-75%; ++++, 76%-100%.

BOX 11.1 Common Tests Utilized in Evaluation of Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

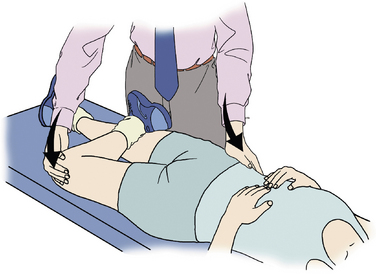

Patrick Test (see Fig. 11-4)

The knee is flexed to 90° on the affected side and the foot is rested on the unaffected knee. Holding the HYPERLINK http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pelvis \o “Pelvis”pelvis firm against the examination table, the affected-side knee is pushed towards the examination table, a maneuver which provides external rotation of the leg at the hip HYPERLINK http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joint \o “Joint”joint. If pain results, this is considered a positive Patrick’s test and sacroiliitis is more likely.

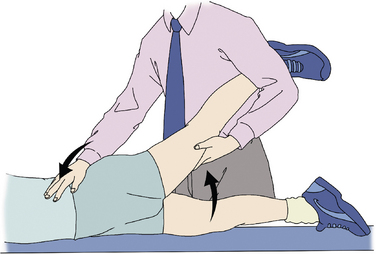

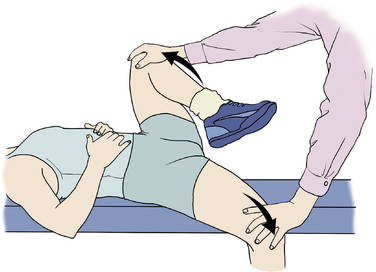

Gaenslen Test (see Fig. 11-3)

Also called the pelvis torsion test.

The hip joint is flexed maximally on one side and the opposite hip joint is extended, stressing both sacroiliac joints simultaneously. This is often done by having the patient lying on his or her back, lifting the knee to push towards the patient’s chest while the other leg is allowed to fall over the side of an examination table, and is pushed toward the floor, flexing both sacroiliac joints. The test can also be performed with the patient in the supine position. The examiner passively flexes the hip while stabilizing the other limb to keep the contralateral limb in a neutral position. The test is considered positive if the patient experiences pain while this test is performed, and may indicate a need for further testing, such as an HYPERLINK http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X-ray \o “X-ray”x-ray or lumbar HYPERLINK http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computer_tomography \o “Computer tomography”CT scan.

Figure 11–3 Gaenslen test is often done by having the patient lying on his or her back, lifting the knee to push towards the patient’s chest while the other leg is allowed to fall over the side of an examination table, and is pushed toward the floor, flexing both sacroiliac joints (See the detail in BOX 11.1).

Complications

Sacroiliac Joint Injection

Complications of SIJ injection are as follows:

Preoperative preparation

Physical Examination

ANATOMY[1]

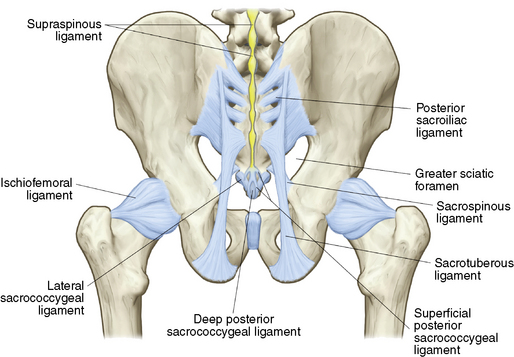

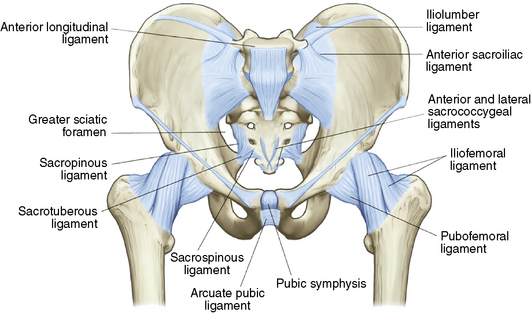

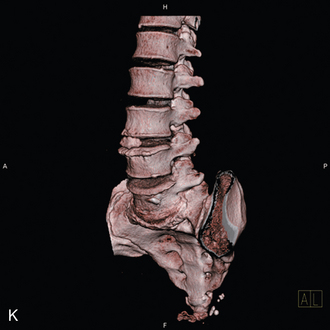

The anatomy of the pelvis is shown in (Figures 11-6 and 11-7):

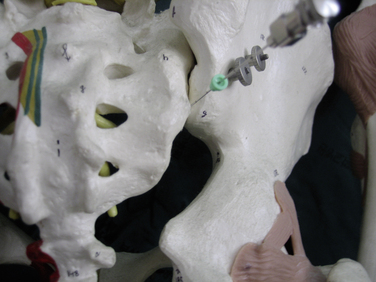

Important aspects of the anatomy of the SIJ (Fig. 11-8) are as follows:

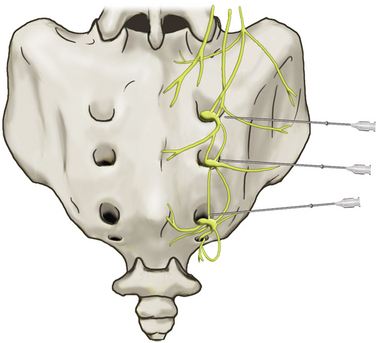

The innervation of the SIJ is extremely complex, and while there is no clear consensus concerning the exact innervation, the most accepted view is described in Box 11.2.

The innervation of the SIJ is extremely complex, and while there is no clear consensus concerning the exact innervation, the most accepted view is described in Box 11.2.Procedures

Sacroiliac Joint Injection

The procedure for sacroiliac joint injection is as follows:

Denervation of the Sacroiliac Joint

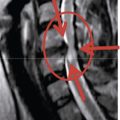

Figure 11–10 Schematic drawing showing the S1-S3 lateral branches innervating the sacroiliac joint and overlying ligaments. The needles depict the approximate location for the diagnostic lumbar branch block.[4]

From Dreyfuss P, Dreyer SJ, Cole A, Mayo K. Sacroiliac joint pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2004;12:255-265.

CASE STUDY 11.1

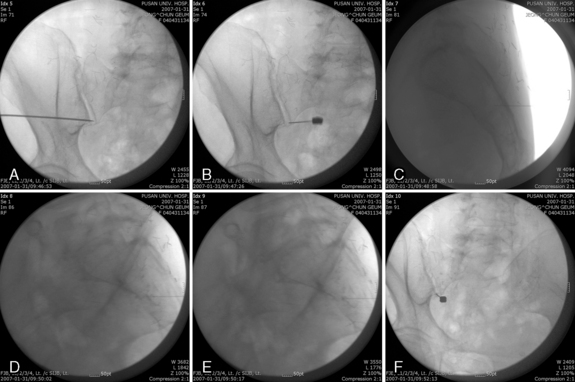

A 76-year-old woman had suffered from low back and left posterior buttock pain without radiating pain below the knee for 3 months. Physical examination elicited positive stress test results and severe tenderness on the left posterior superior iliac spine. The patient underwent sacroiliac joint block. During the procedure the pain source was verified by pain provocation upon application of contrast medium and appropriate anesthetic agents were applied for pain relief (Fig. 11-11).

Postprocedural management

Immediate postprocedure management consists of the following:

The patient should be encouraged to walk and to try to perform a motion that would normally bring about pain.

The patient should be encouraged to walk and to try to perform a motion that would normally bring about pain.1. Cohen S.P. Sacroiliac joint pain: A comprehensive review of anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1440-1453.

2. Dreyfuss P., Dryer S., Griffin J., et al. Positive sacroiliac screening tests in asymptomatic adults. Spine. 1994;19:1138-1143.

3. Schwarzer A.C., Aprill C.N., Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995;20:31-37.

4. Dreyfuss P., Dreyer S.J., Cole A., Mayo K. Sacroiliac joint pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12:255-265.