CHAPTER 119 Sacral Insufficiency Fractures

INTRODUCTION

Insufficiency fractures of the sacrum are an underrecognized cause of low back pain, particularly in the elderly female. To identify these fractures, the astute clinician needs to consider their possibility when evaluating patients with low back pain. Given that insufficiency fractures are more common in elderly patients, their incidence will likely be increasing dramatically with the aging population. Once such fractures are identified as the source of low back pain, the importance of appropriate treatment cannot be overemphasized. Keeping patients functional with healing insufficiency fractures is the mainstay of treatment in order to limit the cost, disability, and complications of immobility from prolonged bed rest. This chapter is dedicated to exploring sacral insufficiency fractures (SIF), highlighting patient characteristics, etiology and biomechanics, clinical presentation, differential diagnosis, appropriate imaging strategies, treatment, and the rare associated complications. The goal of this chapter is to enhance the index of suspicion of SIF to create a higher rate of recognition of these fractures so that patients may receive appropriate treatment.

NOMENCLATURE

Stress fractures are those that occur when the load applied to the bone exceeds the mechanical resistance, typically from repetitive loading of subthreshold forces, as larger forces tend to result in overt fracture rather than stress injuries.1 They are subcategorized into two types: fatigue fractures and insufficiency fractures.2 Fatigue fractures occur in normal, healthy bone from abnormal or repetitive loading. Fatigue fractures commonly occur in the lower extremities of athletes and military recruits, with the most frequent sites being the tibia and metatarsals.3 In contrast, insufficiency fractures occur when the elastic resistance of bone is inadequate to withstand the stresses of normal activity. Insufficiency fractures commonly occur in elderly women with osteoporosis, with the most frequently reported sites being vertebral compression fractures and hip fractures.4 Similarly, pathological fractures occur in weakened bone when the weakening is caused by tumor.

Sacral insufficiency fractures were first described in the medical literature by Lourie in 1982.5 He presented the cases of three patients who were hospitalized for severe low back pain within a 4-month period in 1981. Two were female and one male, between the ages of 75 and 86 years. All three were diagnosed with SIF by bone scan and confirmed with sacral tomograms. The two female patients did well as they were asymptomatic at their follow-up visits 8 and 10 months later. The male patient died of aspiration pneumonia.

CLASSIFICATION OF SACRAL FRACTURES

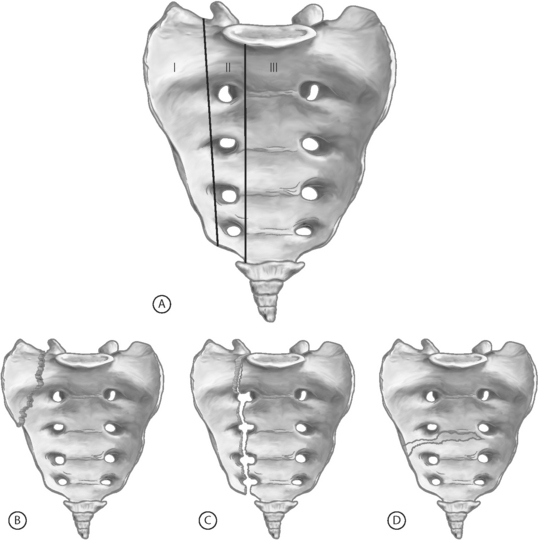

In 1988, Denis and colleagues described the most uniformly accepted classification system for sacral fractures.6 This system divides the sacrum into three zones (Fig. 119.1). Zone I fractures are limited to the sacral ala, the most lateral portion of the sacrum (lateral to the sacral foramina). These are typically stable fractures without an associated neurological deficit. Zone II fractures involve the sacral foramina and are present with sacral, or even L5, radiculopathies. Finally, zone III fractures involve the sacral canal and thus can result in cauda equina-type symptoms. The Denis classification system is best reserved for traumatic sacral fractures, as insufficiency fractures rarely extend beyond the sacral alae (Denis zone I).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The true incidence of SIF in the general population is unknown. Most reports in the literature are case reports and case series, typically of patients admitted to the hospital. As of 2003, there have been just over five hundred reported cases in the literature since the first report in 1982.7 Many of these fractures go unrecognized and likely do not require hospital admission. With this in mind, the incidence reported in the literature varies from 0.2% in all patients (male and female) to 4.3% in females.8–10

The vast majority of cases of SIF are in women with over 90% of the reports in the literature being of females.7–9,11 These fractures are seen most commonly in the elderly with the average age of those reported in the eighth decade of life.7,9,11

The most common location of these fractures is in the sacral ala, typically unilaterally, but they do occur bilaterally. The fractures usually extend vertically, in a line parallel to the sacroiliac joints.12 Sometimes, there is a transverse fracture through the sacral body which, on imaging studies, appears to connect the vertically oriented fractures of the sacral alae.

SIF is commonly associated with other fractures of the pelvic ring, especially the pubis.7,10,12,13 Pubic fractures are typically more readily diagnosed on plain films and, thus, due to their high clinical correlation, searching for a concomitant sacral fracture is appropriate if warranted by the clinical scenario.

In those patients with known osteoporosis, especially those with a prior history of osteoporotic vertebral and/or femoral fractures, a higher index of suspicion for SIF is warranted in those patients who develop low back, buttock, or pelvic pain. In a study of 20 patients diagnosed with SIF, 16 had an associated fracture.9 Nine had pubic rami fractures, one had an iliac fracture, and six had thoracic or lumbar vertebral compression fractures.

ETIOLOGY AND BIOMECHANICS

As the definition implies, insufficiency fractures occur in weakened, demineralized bone due to the reduced elastic resistance of that bone. This weakened bone cannot resist the day-to-day stresses; consequently, these fractures can occur spontaneously. Sometimes very minimal trauma, such as falling from a seated position, is an initiating factor.9

There are multiple factors and associated medical conditions that lead to weakened bone which can result in SIF. The preeminent risk factor is osteoporosis.7,8 Up to three-quarters of patients with SIF have concomitant involutional osteoporosis.11

The second most common risk factor is radiation therapy, primarily for a gynecologic malignancy.8,14 Exposure to radiation weakens bones via many mechanisms.14–16 Radiation can reduce the bony matrix by killing osteocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts. Bony necrosis can occur due to damage of the small feeding arterioles.

Radiation-induced insufficiency fractures typically occur about 12 months after radiation therapy.17 Since these patients have a known primary malignancy, the diagnosis of insufficiency fracture is typically delayed, as a pathologic fracture due to tumor recurrence is generally entertained first. Recognizing insufficiency fractures as a possible cause and obtaining the appropriate imaging can save these postmalignancy patients unnecessary bone biopsies.

Other predisposing factors (Table 119.1) include metabolic diseases other than osteoporosis (osteomalacia, Paget’s disease, renal osteodystrophy, hyperparathyroidism), corticosteroid therapy, rheumatoid arthritis, and fluoride therapy.8,13,18 Association with solid organ transplantation (liver, lung, heart, and kidney) has been described as well.19–21 Two reports of Tarlov’s cysts as the precipitating etiology for SIF exist.8,22 There are also mechanical causes which may predispose a person to SIF. These include lumbar scoliosis and total hip arthroplasty.18,23,24

| Osteoporosis | Hyperparathyroidism |

| Radiation therapy to the pelvis | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Corticosteroid therapy | Fluoride therapy |

| Osteomalacia | Solid organ transplantation |

| Paget’s disease | Tarlov’s cysts |

| Renal osteodystrophy | Anorexia nervosa |

There has been very limited research into these biomechanical causes. Given the common location of such fractures (vertically extending in the sacral alae, running parallel to the sacroiliac joints, in line with the lateral margins of the lumbar spine) a hypothesis has been developed which suggests that these fractures may be partially caused by weight-bearing loads transmitted through the lumbar spine.12

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Most patients with a SIF present with low back pain. In addition, some describe buttock and pelvic pain. Rarely are there complaints other than pain.8,25,26 Radicular pain is rare.8 The axial pain is often severe, incapacitating, and mechanical in nature, exacerbated by weight-bearing or physical exertion and relieved with rest.21,27 Some patients are nonambulatory because of the severity of pain.26 There is typically a history of minimal trauma, such as fall from a seated or standing position. Sometimes there is no known trauma.

Neurologic abnormalities in patients with SIF are exceedingly rare due to the absence of bony displacement and sacral foraminal compromise in most patients, and thus little or no injury to the sacral roots. There are only a few reports of neurologic complications related to SIF.28–30 The reports include one case of urinary retention and anal sphincter dysfunction in a patient with a markedly displaced fracture28 and one with urinary and fecal incontinence, decreased anal sphincter tone, and lower extremity weakness.29 In another case series of three patients, there were similar findings of urinary incontinence and decreased anal sphincter tone, but also of definite lower extremity motor loss (confirmed by EMG).30 In a 1997, in a meta-analysis of 493 patients with SIF, a total of 12 cases reported neurologic symptoms, a 2% incidence.11

The physical examination of a patient with SIF is generally unrevealing. The most common finding, if any, is sacral tenderness.8 Restricted lumbar spine motion is next most common – a typical finding in the general elderly population.8,10 In general, the neurologic examination is normal, or age appropriate.

IMAGING STUDIES

Conventional radiographs

Plain radiographs of the sacrum are generally the first imaging studies used to screen for SIF. Though appropriate as an initial screening tool, they are often falsely negative due to difficulty in interpretation as overlying bowel gas, vascular calcifications, and the normal angulation of the sacrum make the diagnosis of such fractures problematic on plain films.31 Demineralization of bone in elderly patients also often results in plain radiographs that are difficult to interpret.

The most common finding on conventional radiographs that lead one to suspect SIF is areas of vertical sclerosis in the sacral alae. These sclerotic areas represent callus formation. In a case series of 27 patients, 37% of the radiographs had this finding.7 Other studies showed 52–75% of plain sacral radiographs were considered normal, even retrospectively.8,18

Pelvic ring fractures (particularly in the pubic ramus) are more easily seen on conventional radiographs. If these are found, an even higher index of suspicion should be raised for an associated radiographically occult sacral fracture since 47% of patients with SIF had a concomitant pubic insufficiency fracture present in one meta-analysis of 212 patients.8

Scintigraphy

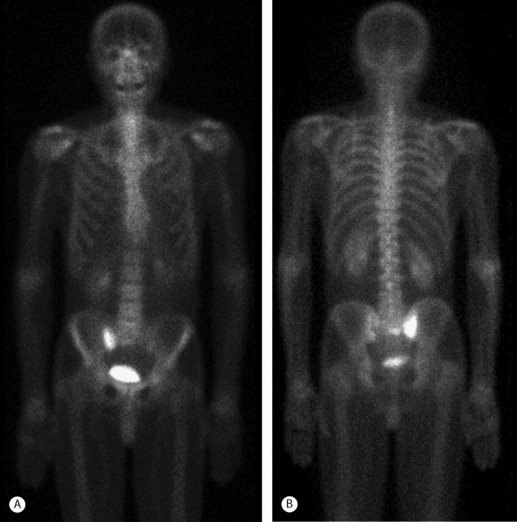

Radionuclide bone scanning is the most sensitive technique to detect SIF and thus should be the imaging study of choice when conventional radiographs are inconclusive. In addition to their high sensitivity, bone scans are widely used because they can provide positive detection very early after fracture onset (typically 48–72 hours).32 Sacral fractures are best demonstrated on the posterior view.33 A characteristic scintigraphic finding is the H-shaped (or butterfly) sacral pattern.34,35 This ‘H’ shape has been labeled the ‘Honda’ sign (Fig. 119.2).36

The H-shaped pattern is produced by two vertical bands in both sacral alae interconnected by a horizontal component through the body of the sacrum. This pattern, though pathognomonic for SIF, is not seen in a majority of cases. Reports detailing this scintigraphic appearance are seen 20–45% of the time.8,31 More common sacral patterns include variable parts of the ‘H’ shape: bilateral vertical bars in the sacral alae with partial or no horizontal bar through the sacral body and unilateral alar uptake, again with partial or no horizontal uptake (Fig. 119.3A, B).35,37 This more patchy appearance mimics a primary malignancy or metastatic disease; thus, further evaluation with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is required, especially in patients with a history of previous malignancy.31

Fig. 119.3 Technetium 99 bone scan of a 68-year-old male with advanced osteoporosis and right buttock pain. These anterior (A) and posterior (B) coronal views of the pelvis show increased radiotracer medial to the right SI joint demonstrating the sacral alar insufficiency fracture confirmed by the MRI in Fig. 119.4.

Computed tomography

Computed tomography of the pelvis is best used to confirm the presence of fracture when one is still not certain after bone scanning. In patients with a history of previous malignancy, CT can often prevent the need for unnecessary biopsy. The appearance of SIF on CT includes bands of bony sclerosis with or without evident fracture lines within the sacral alae.38 CT is also very helpful in determining fracture displacement and fragmentation as well as bony destruction and soft tissue masses seen in malignancy.32

Reports in the literature demonstrate an 88% detection rate of SIF by CT.7,38 An early finding of SIF on CT, in addition to the sclerosis before the distinct fracture lines develop, is intraosseous gas inclusions in the ventral lateral sacrum.39 As fracture lines can take weeks to months to evolve, these early findings are very useful to make or confirm the diagnosis of SIF.

Magnetic resonance imaging

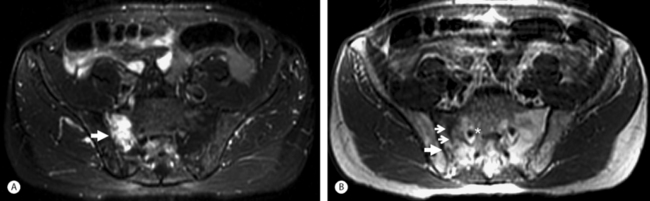

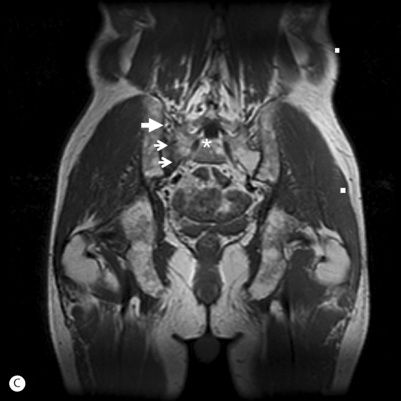

Magnetic resonance imaging is highly sensitive for the diagnosis of SIF but the marrow edema seen is somewhat non-specific, and can also be seen with metastatic disease. The marrow edema seen is of low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and STIR images (Fig. 119.4).33 As with CT, a discrete fracture line may not be evident with MRI and thus marrow edema may be the only finding. An injection of intravenous gadolinium may reveal the fracture line, as it did in the majority of cases in one study where the fracture line was not evident without contrast.40 MR fat suppression sequences also can help to reveal the fracture line.40 There is a delay in MRI findings, with the earliest sign of marrow edema not evident until at least 18 days after the onset of symptoms;37 thus, MRI is used similarly as CT, to confirm the diagnosis made by bone scanning.

Fig. 119.4 (A) MRI of the pelvis in a 68-year-old male (same as in Fig. 119.3) with advanced osteoporosis. This is an axial STIR image showing the bone marrow edema surrounding (and obscuring) the right sacral alar (zone I) insufficiency fracture. (B) This is an axial T1-weighted image showing the vertically oriented (small arrows) area of low T1 signal representing the right sacral alar insufficiency fracture. The larger arrows are pointing at the right SI joint. The asterisk is just medial to the right S1 neuroforamen.

(C) This is a coronal T1-weighted image showing a different depiction of the same SIF in (B).

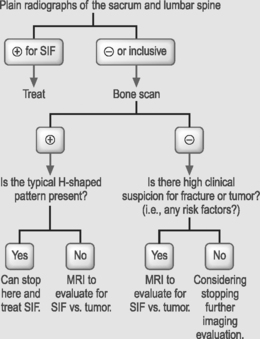

Imaging recommendations

Conventional radiographs are an appropriate screening tool for SIF and should be obtained initially. If the plain film is inconclusive, a bone scintigram should be obtained. If increased uptake is not in the pathognomonic H-shaped pattern, CT or MRI should be obtained to differentiate an insufficiency fracture from neoplasm, as primary or metastatic bone lesions do not have a characteristic vertical, linear, or band shape in the sacral alae.37 With this imaging protocol strategy, unnecessary sacral biopsies should be limited or nonexistent. See Table 119.2 for a flow diagram of a typical clinical scenario with an imaging studies decision tree.

Table 119.2 Diagnosis of sacral insufficiency fractures: typical clinical paradigm of elderly woman with low back and buttock pain

| History | Examination | Imaging |

|---|---|---|

|

||

OTHER DIAGNOSTIC MANEUVERS

Serologic evaluation is limited and rarely necessary in making a diagnosis of SIF. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and alkaline phosphatase may be mildly elevated in certain patients with SIF.8,21,26 However, these findings are not specific to SIF.

TREATMENT

There is not one randomized, controlled trial studying treatment efficacy for SIF. Treatment has been based on anecdotal evidence and what intuitively has seemed appropriate. Only recently has one of the main standards of treatment (bed rest) been challenged.41

Pain management

Analgesics

Analgesics should be used liberally for pain control, but remember that the elderly are more prone to medication side effects and lower tolerance. The routine analgesics for SIF include acetaminophen and a short course of opiates if necessary. Calcitonin nasal spray can be used to treat bone pain and has been reported to have good pain-relieving effects in patients.9,27 Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be used as second-line treatment since there are some reports implicating NSAID use with delayed fracture healing.42

Activity limitation

Bed rest was an early mainstay of treatment and generally quite helpful in initial pain control. However, given the multitude of complications resulting from immobility and bed rest (as amplified in Chapter 111 by Terry Sawchuk and Eric Mayer) and the fact these issues are amplified in the elderly, this strategy must be reconsidered.41 Since these fractures are generally stable, bed rest was used primarily for pain control. A better solution regarding activity level is to instruct the patient to stay mobile and instead use pain as a guide for activity limitations.

Prevention of complications

Early ambulation (as opposed to bed rest) decreases the risk of the many complications secondary to immobilization. The effects of immobilization spares virtually no organ system.41 These adverse effects include muscle weakness and strength deficits, deep venous thrombosis, postural hypotension, impaired cardiac function, urinary retention, constipation, and pressure ulcers, all of which can create a higher level of patient disability.

The other main group of complications to prevent during this time are those inherently related to osteoporosis and the risk of future fracture. If aggressive osteoporosis management (see Ch. 39 by Joseph Lane et al.) has not already been initiated, it should not be overlooked. Bisphosphonates should be considered, as should a work-up for the etiology of osteoporosis if it is not readily apparent. Preventing a potentially more catastrophic and disabling femoral or vertebral fracture is the goal.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Due to the inherent stability of these fractures, lack of neurological complications, the high rate of improvement with conservative measures, and the low rate of nonunion, surgery for SIF is exceedingly rare. Mears and Velyvis authored the only published report examining surgical management for persistent pain and nonunion after SIF.43 They performed in situ fixations in 36 patients with chronic pain and nonunion of sacral alae insufficiency fractures. The surgery was successful in creating pelvic stability and fracture unions; however, subjective reports of patients’ pain and disability were not overwhelmingly positive.

NEW HORIZONS: INTERVENTIONAL TREATMENT

There has been recent work to create a technique for SIF analogous to vertebroplasty for compression fractures. Garant44 and Pommersheim et al.45 have published four cases detailing this technique. Since percutaneous polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) injection has been adapted to treat painful metastatic lesions in the S1 vertebral body,46 the technique has been adapted to treat the pain of SIF. The technique, called sacroplasty, is similar to that used in vertebroplasty. With all four cases, good pain relief and functional improvement after the procedure were demonstrated. However, there are no long-term results to date. Though this technique looks promising, there is no necessary role for invasive procedures with inherent risks in such a relatively benign disease process which has generally excellent long-term outcomes with more conservative management. Its value may be in keeping mobile patients whose pain is uncontrolled by other means.

TREATMENT OUTCOMES

Outcomes of SIF treatments are rarely reported but, in general, are quite favorable. The pain, as a rule, resolves typically in the range from 2 weeks to 2 years, with most SIF patients experiencing complete pain relief within 6–12 months.7–9,18,26 Recovery is generally prolonged in patients with associated pubic fractures.8 Most patients do not suffer any prolonged functional loss and most remain independent ambulators. The small minority of patients who do not do as well generally have other confounding medical conditions which limit their mobility and functional status, or suffer other osteoporotic fractures.

COMPLICATIONS

Complications from SIF are rare. In general, these are stable fractures with very little risk of complications. The most common complications are seen in those patients treated with bed rest who suffer the consequences of immobility.41

Since these fractures are generally limited to the sacral alae, neurological complications are rare. There have been only a few reports of neurologic damage, to include variants of cauda equina syndrome or sacral radiculopathies.28–30 There is no characteristic of the fracture, such as amount of angulation or displacement, to reliably predict a risk of neurological complications. Finally, as previously mentioned, other complications such as nonunion or persistent pain are also exceedingly rare.

1 Orava S, Hulkko A. Delayed unions and nonunions of stress fractures in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(4):378-382.

2 Pentecost RL, Murray RA, Brindley HH. Fatigue, insufficiency and pathologic fractures. JAMA. 1964;187:1001-1004.

3 Bennell KL, Brukner PD. Epidemiology and site specificity of stress fractures. Clin Sports Med. 1997;6:179-196.

4 Cummings SR, Melton LJIII. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet. 2002;359:1761-1767.

5 Lourie H. Spontaneous osteoporotic fracture of the sacrum. An unrecognized syndrome of the elderly. JAMA. 1982;60:440-452.

6 Denis F, Davis S, Comfort T. Sacral fractures: an important problem. Retrospective analysis of 236 cases. Clin Orthop. 1988;227:67-81.

7 Soubrier M, Dubost JJ, Boisgard S, et al. Insufficiency fracture. A survey of 60 cases and review of the literature. Joint Bone Spine. 2003;70:209-218.

8 Grasland A, Pouchot J, Mathieu A, et al. Sacral insufficiency fractures: An easily overlooked cause of back pain in elderly women. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(6):668-674.

9 Weber M, Hasler P, Gerber H. Insufficiency fractures of the sacrum: Twenty cases and review of the literature. Spine. 1993;18:2507-2512.

10 Peh WCG, Khong PL, Ho WY. Insufficiency fractures of the sacrum and os pubis. Br J Hosp Med. 1995;54:15-19.

11 Finiels H, Finiels PJ, Jacquot JM, et al. Fractures of the sacrum caused by bone insufficiency. Meta-analysis of 508 cases. Presse Med. 1997;26(33):1568-1573.

12 Leroux JL, Denat B, Thomas E, et al. Sacral insufficiency fractures presenting as acute low-back pain. Biomechanical aspects. Spine. 1993;18(16):2502-2506.

13 DeSmet AA, Neff JR. Pubic and sacral insufficiency fractures: clinical course and radiologic findings. Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145:601-606.

14 Bliss P, Parsons CA, Blake PR. Incidence and possible aetiological factors in the development of pelvic insufficiency fractures following radical radiotherapy. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;69:544-548.

15 Henry AP, Lachmann E, Tunkel RS, et al. Pelvic insufficiency fractures after irradiation: diagnosis, management and rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77(4):414-416.

16 Libshitz HI. Radiation changes in bone. Semin Roentgenol. 1994;29:15-37.

17 Blomlie V, Rofstad EK, Talle K, et al. Incidence of radiation-induced insufficiency fractures of the female pelvis: evaluation with MR imaging. Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:120-1210.

18 Gotis-Graham I, McGuigan L, Diamond T, et al. Sacral insufficiency fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1994;76(6):882-886.

19 Peris P, Navasa M, Guanabens N, et al. Sacral stress fracture after liver transplantation. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32(8):702-704.

20 Schulman LL, Addess O, Staron RB, et al. Insufficiency fractures of the sacrum: a cause of low back pain after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1997;16(10):1081-1085.

21 Aretxabala I, Fraiz E, Perez-Ruiz F, et al. Sacral insufficiency fractures. High association with pubic rami fractures. Clin Rheumatol. 2000;19:399-401.

22 Peh WCG. Tarlov cysts: another cause sacral insufficiency fractures? Clin Radiol. 1992;46:329-330.

23 Cooper KL. Insufficiency stress fractures. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 1994;23:29-68.

24 Cotty PH. Insufficiency fractures of the sacrum: Ten cases and a review of the literature. J Neuroradiol. 1989;16:160-171.

25 Mathers DM, Major GA, Allen L, et al. Insufficiency fractures of the sacrum. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52:621-623.

26 Rawlings CE, Wilkins RH, Martinez S, et al. Osteoporotic sacral fractures: a clinical study. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:72-76.

27 Lin J, Lachmann E, Nagler W. Sacral insufficiency fractures: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. J Women’s Health and Gender-Based Med. 2001;10:699-705.

28 Jones JW. Insufficiency fracture of the sacrum with displacement and neurologic damage: a case report and review of the literature. J Am Geriatric Soc. 1991;39:280-283.

29 Lock SH, Mitchell SC. Osteoporotic sacral fracture causing neurologic deficit. Br J Hosp Med. 1993;49:210.

30 Jacquot JM, Finiels H, Fardjad S. Neurological complications in insufficiency fractures of the sacrum: three case reports. Rev Rheum. 1999;66:109-114.

31 White JH, Hague C, Nicolaou S, et al. Imaging of sacral fractures. Clin Radiol. 2003;58:914-921.

32 Martin P. The appearance of bone scans following fractures, including immediate and long-term studies. J Nucl Med. 1979;20:1227.

33 Peh WCG, Khong PL, Yin Y. Imaging of pelvic insufficiency fractures. Radiographics. 1996;16:335-348.

34 Ries T. Detection of osteoporotic sacral fractures with radionuclides. Radiology. 1983;146:783-785.

35 Schneider R, Yacovone J, Ghelman B. Unsuspected sacral fractures: detection by radionuclide bone scanning. Am J Roentgenol. 1985;144:337-341.

36 Stroebel RJ. Sacral insufficiency fractures. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:117-119.

37 Jones DN, Wycherley AG. Bone scan demonstration of progression of sacral insufficiency stress fracture. Australasian Radiol. 1994;38:148-150.

38 Chen CKH, Liang HL, Lai PH, et al. Imaging diagnosis of insufficiency fracture of the sacrum. Chin Med J (Taipei). 1999;62:591-597.

39 Stäbler A, Steiner W, Kohz P, et al. Time-dependent changes of insufficiency fractures of the sacrum: intraosseous vacuum phenomenon as an early sign. Eur Radiol. 1996;6:655-657.

40 Grangler C, Garci AJ, Howarth NR. Role of MRI in the diagnosis of insufficiency fractures of the sacrum and acetabular roof. Skeletal Radiol. 1997;26:517-524.

41 Babayev M, Lachmann E, Nagler W. The controversy surrounding sacral insufficiency: to ambulate or not to ambulate? Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;79:404-409.

42 Giannoudis PV, Macdonald DA, Matthews SJ, et al. Nonunion of the femoral diaphysis. The influence of reaming and non-steriodal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2000;82-B(5):655-658.

43 Mears DC, Velyvis JH. In situ fixation of pelvic nonunions following pathologic and insufficiency fractures. J Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84:721-728.

44 Garant M. Sacroplasty: a new treatment for sacral insufficiency fracture. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:1265-1267.

45 Pommersheim W, Huang-Hellinger F, Baker M, et al. Sacroplasty: a treatment for sacral insufficiency fractures. Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1003-1007.

46 Dehdashti AR, Martin JB, Jean B, et al. PMMA cementoplasty in symptomatic metastatic lesions of the S1 vertebral body. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2000;23:235-241.