S

S-100β protein. Calcium-binding protein present in glial cells, studied as an early marker of damage to the blood–brain barrier, e.g. after CVA, head injury, cardiac surgery and neurosurgery. A normal level reliably excludes significant CNS injury. Metabolised in the kidney with a half-life of ~25 min, the serum concentration is usually negligible but increases after brain injury, although it is thought that S-100β may also be produced from other tissues and its relationship with functional impairment is uncertain.

Cata JP, Abdelmalak B, Farag E (2012). Br J Anaesth; 107: 844–58

S wave, Downward deflection following the R wave of the ECG (see Fig. 59b; Electrocardiography). Its size usually decreases from V2 to V6; the deepest wave is normally less than 30 mm. Prominence in standard leads I, II and III (S1S2S3 pattern) may be normal in young people but may be associated with right ventricular hypertrophy. May also be seen in MI along with other changes.

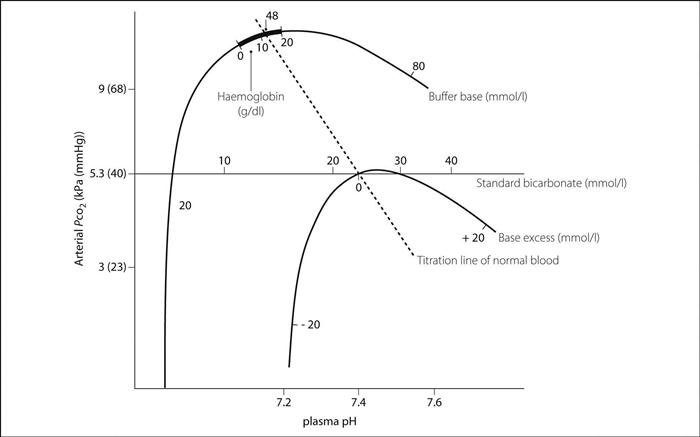

Sacral canal. Cavity, 10–15 cm long and triangular in section, running the length of the sacrum, itself formed from five fused sacral vertebrae (Fig. 136). Continuous cranially with the lumbar vertebral canal. The anterior wall is formed by the fused bodies of the sacral vertebrae, and the posterior walls by the fused sacral laminae. Due to failure of fusion of the fifth laminar arch, the posterior wall is deficient between the cornua, forming the sacral hiatus, which is covered by the sacrococcygeal membrane (punctured during caudal analgesia). Congenital variants of fusion are common, e.g. deficient fusion of several laminae; this is thought to be a contributing cause of unreliability of caudal analgesia. The canal contains the termination of the dural sac at S2, the sacral nerves and coccygeal nerve, the internal vertebral venous plexus and fat. Its average volume in adults is 32 ml in females and 34 ml in males.

Crighton IM, Barry BP, Hobbs GJ (1997). Br J Anaesth; 78: 391–5

Sacral nerve block, see Caudal analgesia

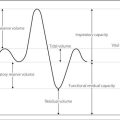

Sacral plexus. Supplies the pelvic and hip muscles, and the skin of the buttock and posterior thigh. Lies on piriformis muscle on the posterior wall of the pelvis, deep to the pelvic fascia, and is formed from the anterior primary rami of L4–S4 (Fig. 137). Its major branches are the sciatic, pudendal and gluteal nerves.

Fig. 137 Plan of the sacral plexus

Saddle block, see Spinal anaesthesia

Safe transport and retrieval (STaR). Course conceived by the Advanced Life Support Group and first run in 1998. Teaches a systematic approach to the safe transfer and retrieval of critically ill and injured patients. Aimed at doctors, nurses and paramedics.

Salbutamol. β-Adrenergic receptor agonist, used mainly as a bronchodilator drug. Relatively selective for β2-receptors, although it does cause β1-receptor stimulation. Undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism if given orally, thus usually administered by inhalation or iv. Produces bronchodilatation within 15 min; effects last 3–4 h. May also reduce the release of histamine and inflammatory mediators from mast cells sensitised with IgE, hence its particular use in asthma.

Also used as a tocolytic drug in premature labour and to improve cardiac output in low perfusion states, via β2-receptor-mediated smooth muscle relaxation in the uterus and blood vessels respectively.

• Dosage:

500 µg im/sc, 4-hourly as required.

500 µg im/sc, 4-hourly as required.

1–2 puffs by aerosol (100–200 µg) tds/qds. 200–400 µg is recommended for dry powder inhalation, since bioavailability for the latter is lower.

1–2 puffs by aerosol (100–200 µg) tds/qds. 200–400 µg is recommended for dry powder inhalation, since bioavailability for the latter is lower.

2.5–5 mg by nebulised solution, 4–6-hourly.

2.5–5 mg by nebulised solution, 4–6-hourly.

• Side effects: tachycardia, tremor, headache. Hypokalaemia may occur with prolonged use. Pulmonary oedema may occur after use for tocolysis.

Salicylate poisoning. Usually acute but may be chronic, especially in children.

hyperventilation results from direct respiratory centre stimulation, possibly via central uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation. Respiratory alkalosis results. Compensatory renal excretion of bicarbonate results in urinary water and potassium loss with dehydration and hypokalaemia.

hyperventilation results from direct respiratory centre stimulation, possibly via central uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation. Respiratory alkalosis results. Compensatory renal excretion of bicarbonate results in urinary water and potassium loss with dehydration and hypokalaemia.

metabolic acidosis is caused by the salicylic acid, and its metabolic effects (increased production of ketone bodies, lactic acid and pyruvic acid, hyperglycaemia or hypoglycaemia). Thus the urine, initially alkaline, becomes acid.

metabolic acidosis is caused by the salicylic acid, and its metabolic effects (increased production of ketone bodies, lactic acid and pyruvic acid, hyperglycaemia or hypoglycaemia). Thus the urine, initially alkaline, becomes acid.

arrhythmias, hypotension.

arrhythmias, hypotension.

convulsions, pulmonary oedema, hyperthermia and acute kidney injury may occur.

convulsions, pulmonary oedema, hyperthermia and acute kidney injury may occur.

impaired coagulation is rarely significant.

impaired coagulation is rarely significant.

general measures as for poisoning and overdose, e.g. O2 therapy, iv fluid administration. Activated charcoal (1 mg/kg) should be given to all patients who have ingested > 150 mg/kg or those who are acutely symptomatic. Additional doses may be given if serum salicylate levels continue to rise.

general measures as for poisoning and overdose, e.g. O2 therapy, iv fluid administration. Activated charcoal (1 mg/kg) should be given to all patients who have ingested > 150 mg/kg or those who are acutely symptomatic. Additional doses may be given if serum salicylate levels continue to rise.

increased elimination may be indicated if plasma levels exceed 500 mg/l (3.6 mmol/l) in adults or 300 g/l (2.2 mmol/l) in children. Techniques include forced alkaline diuresis, dialysis and haemoperfusion.

increased elimination may be indicated if plasma levels exceed 500 mg/l (3.6 mmol/l) in adults or 300 g/l (2.2 mmol/l) in children. Techniques include forced alkaline diuresis, dialysis and haemoperfusion.

Mortality of acute overdose is approximately 2%; mortality of chronic overdose about 25%.

Salicylates. Group of NSAIDs derived from salicylic acid. Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) is the most commonly used; others are available but are less potent, e.g. sodium salicylate. Have anti-inflammatory and antipyretic effects; they inhibit both central and peripheral synthesis of prostaglandins. Inhibit platelet and vascular endothelial cyclo-oxygenase; at low dosage, they selectively inhibit platelet cyclo-oxygenase. They are thus used as antiplatelet drugs. Effects on platelets are irreversible, lasting until new platelets are synthesised (7–10 days).

Used for mild-to-moderate pain, pyrexia, rheumatic fever, rheumatoid arthritis, and peripheral and coronary artery disease. Contraindicated in gout as they may impair excretion of uric acid.

Absorbed rapidly from the upper GIT after therapeutic dosage, with peak plasma levels within 2 h of ingestion. Absorption is determined by the composition of tablets, intestinal pH and gastric emptying. About 90% protein-bound, they compete with other substances for protein binding sites, e.g. thyroxine, penicillin, phenytoin. Metabolised in the liver and excreted mainly in the urine, especially if the latter is alkaline. Half-life is about 15 min, but is very dependent on the dose taken.

• Side effects: as for NSAIDs and salicylate poisoning. Implicated in causing Reye’s syndrome in children.

Contraindicated in children < 16 years and patients with peptic ulcer disease; used with caution in those with coagulation disorders or taking anticoagulant drugs.

Saline solutions. IV fluids containing sodium chloride, used extensively to replace sodium and ECF losses, e.g. in dehydration, and perioperatively. A 0.9% solution is most commonly used (‘physiological saline’, often erroneously called ‘normal saline’); other saline-containing solutions include Hartmann’s solution, Ringer’s solution and dextrose/saline mixtures. Twice ‘normal’ saline (1.8%) is used in hyponatraemia, and up to 7.5% solutions have been used (largely experimentally) in hypovolaemic shock.

Samples, statistical. Parts of populations, selected for statistical tests or analysis. In order to represent the true population, samples should be as large as possible to ensure appropriate power, and free of bias; i.e. should be random. Matched samples refer to groups matched for possible confounding variables, allowing better comparison of the desired measurements. Optimum matching occurs when subjects act as their own controls (i.e. measurements are paired).

Sanders oxygen injector, see Injector techniques

Saphenous nerve block, see Ankle, nerve blocks; Knee, nerve blocks

Diagnosed on clinical grounds, supported by tissue biopsy, CXR, hypercalcaemia (due to derangement of vitamin D metabolism), raised angiotensin converting enzyme levels and positive Kveim test (granuloma formation following intradermal injection of sarcoid tissue suspension).

Anaesthetic and ICU considerations include the possibility of pulmonary fibrosis, cardiac failure, heart block, laryngeal fibrosis, renal failure and hypercalcaemia. Corticosteroids are often prescribed.

[Morten A Kveim (1892–1967), Norwegian pathologist]

Dempsey OJ, Paterson EW, Kerr KM, Denison AR (2009). Br Med J; 339: 620–5

Saturated vapour pressure (SVP). Pressure exerted by the vapour phase of a substance, when in equilibrium with the liquid phase. Indicates the degree of volatility; e.g. for inhalational anaesthetic agents, diethyl ether (SVP 59 kPa [425 mmHg]) is more volatile and easier to vaporise than halothane (SVP 32 kPa [243 mmHg]). SVP increases with temperature, therefore SVPs of volatile agents are quoted at standard temperature (usually 20°C). At boiling point, SVP equals atmospheric pressure.

Scalp, nerve blocks. Local anaesthetic infiltration is usually performed with added adrenaline, because of the rich vascular supply of the scalp. Injection is performed first in the subcutaneous tissue above the aponeurosis (where nerves and vessels lie), then below. Infiltration in a band around the head, above the ears and eyebrows, provides anaesthesia of the scalp. Individual branches of the maxillary nerve may also be blocked. The occipital nerves supplying the posterior scalp may be blocked by infiltrating between the mastoid process and occipital protuberance on each side.

Scavenging. Removal of waste gases from the expiratory port of anaesthetic breathing systems; desirable because of the possible adverse effects of exposure to inhalational anaesthetic agents. Adsorption of volatile agents using activated charcoal (Aldasorber device) has been used but does not remove N2O.

• Scavenging systems consist of:

collecting system: usually a shroud enclosing the adjustable pressure limiting valve. For paediatric breathing systems, several attachments have been described, including various connectors and funnels.

collecting system: usually a shroud enclosing the adjustable pressure limiting valve. For paediatric breathing systems, several attachments have been described, including various connectors and funnels.

receiving system: incorporates a reservoir to enable adequate removal of gases, even if the volume cleared per minute is less than peak expiratory flow rate. May use rubber bags or rigid bottles. If the system is closed, a dumping valve and pressure-relief valve are required to prevent excess negative or positive pressure, respectively, being applied to the patient’s airway. Vents are often present in rigid reservoirs. Requirements:

receiving system: incorporates a reservoir to enable adequate removal of gases, even if the volume cleared per minute is less than peak expiratory flow rate. May use rubber bags or rigid bottles. If the system is closed, a dumping valve and pressure-relief valve are required to prevent excess negative or positive pressure, respectively, being applied to the patient’s airway. Vents are often present in rigid reservoirs. Requirements:

– negative pressure: maximum 0.5 cmH2O at 30 l/min gas flow.

– assisted passive: employs the air-conditioning system’s extractor ducts.

– active: uses a dedicated fan system or ejector flowmeter. Requires a low-pressure high-volume system (able to remove 75 l/min with a peak flow of 130 l/min); thus hospital suction equipment is unsuitable.

Workplace exposure limits set out in COSHH regulations for Great Britain and Northern Ireland are 100 ppm N2O, 50 ppm enflurane/isoflurane and 10 ppm halothane (each over an 8-h period). Maximum permitted levels vary between countries; e.g. in the USA, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has recommended an 8-h time-weighted average limit of 2 ppm for halogenated anaesthetic agents in general (0.5 ppm together with exposure to N2O).

Schimmelbusch mask, see Open-drop techniques

Sciatic nerve block, Used for surgery to the lower leg, often combined with femoral nerve block, obturator nerve block and lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh block (see Fig. 66; Femoral nerve block). May also be performed to provide analgesia after fractures, or sympathetic nerve block of the foot.

The sciatic nerve (L4–S3) arises from the sacral plexus, leaving the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen beneath the piriformis muscle, and between the ischial tuberosity and the greater trochanter of the femur. It becomes superficial at the lower border of gluteus maximus, and runs down the posterior aspect of the thigh to the popliteal fossa, where it divides into tibial and common peroneal nerves. It supplies the hip and knee joints, posterior muscles of the leg and skin of the leg and foot below the knee, except for the medial calf. The posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh runs close to it and is usually blocked by it.

• Four different approaches are commonly used:

posterior: with the patient lying with the side to be blocked uppermost, and the uppermost hip and knee flexed, a line is drawn between the greater trochanter and posterior superior iliac spine. At the line’s midpoint, a perpendicular is dropped 3 cm, and a 12 cm needle introduced at this point, at right angles to the skin. The nerve lies on the ischial spine and is identified using a nerve stimulator (seeking contraction of the hamstrings and muscles of the back of the lower leg and foot). 15–30 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected. Onset of blockade may take 30 min.

posterior: with the patient lying with the side to be blocked uppermost, and the uppermost hip and knee flexed, a line is drawn between the greater trochanter and posterior superior iliac spine. At the line’s midpoint, a perpendicular is dropped 3 cm, and a 12 cm needle introduced at this point, at right angles to the skin. The nerve lies on the ischial spine and is identified using a nerve stimulator (seeking contraction of the hamstrings and muscles of the back of the lower leg and foot). 15–30 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected. Onset of blockade may take 30 min.

Scleroderma, see Systemic sclerosis

Scoliosis, see Kyphoscoliosis

Scopolamine, see Hyoscine

Scribner shunt, see Shunt procedures

Second. SI unit of time; defined according to the frequency of radiation emitted by caesium-133 in its lowest energy (ground) state.

Second gas effect. Increased alveolar concentration of one inhalational anaesthetic agent caused by uptake of a second inhalational agent. Most marked when the second gas occupies a large volume, e.g. N2O. Analogous but opposite to the Fink effect at the end of anaesthesia.

Second messenger. Intracellular substance (e.g. cAMP, calcium ions) linking extracellular chemical messengers (first messengers) with the physiological response. G protein-coupled receptors are often involved in second messenger systems.

Sedation. State of reduced consciousness in which verbal contact with the patient may be maintained. Used to reduce discomfort during unpleasant procedures, e.g. regional anaesthesia, dental surgery, endoscopy, cardiac catheterisation, and on ICU. For short procedures, drugs of short duration of action causing minimal cardiorespiratory depression are preferable. Best control is usually achieved with iv administration, although other routes may be used, e.g. oral premedication. Routine monitoring should be employed during procedures as for general anaesthesia. Drugs may be given by intermittent bolus, or by continuous infusion; the latter is easier to titrate. The level of sedation required depends on the individual patient and the procedure performed. Patient-controlled sedation has been used during procedures performed under local or regional anaesthesia; the patient uses a patient-controlled analgesia device containing e.g. propofol as required.

On ICU, sedative and analgesic drugs are given to reduce pain, distress and anxiety, and to aid tolerance of tracheal tubes, IPPV, tracheal suction and physiotherapy. Cardiovascular depression is undesirable, although respiratory depression may be an advantage if IPPV is required. Long-term administration is often required; thus side effects not seen after brief administration may occur, and drugs with long half-lives may accumulate. The desired end-point is usually a calm, cooperative patient who can respond to commands, with deeper levels of sedation provided for stimulating procedures. Sedation scoring systems have been devised to assist titration of drugs.

• The following drugs have been used for sedation in ICU or for short procedures:

opioid analgesic drugs: commonly used on ICU. Provide analgesia and euphoria, and aid toleration of IPPV. All produce respiratory depression. Hypotension is particularly likely if hypovolaemia is present and following rapid iv injection. GIT motility is reduced. Drugs used include:

opioid analgesic drugs: commonly used on ICU. Provide analgesia and euphoria, and aid toleration of IPPV. All produce respiratory depression. Hypotension is particularly likely if hypovolaemia is present and following rapid iv injection. GIT motility is reduced. Drugs used include:

– morphine 2.5–5 mg boluses (20–60 µg/kg/h infusion). Accumulation of metabolites may occur after prolonged infusion, especially in renal failure. Increased susceptibility to infection has been shown in experimental animals receiving very large doses.

– fentanyl 1–5 µg/kg/h; accumulation readily occurs after prolonged infusion, since its short duration of action initially is due to redistribution, and clearance is slower than that of morphine.

– alfentanil 30–60 µg/kg/h; accumulation is less likely than with fentanyl.

– remifentanil 0.025–0.1 mg/kg/min (with or without an initial dose of e.g. 0.5 mg/kg/min) is also used, either alone or in combination with propofol/midazolam.

benzodiazepines: often used in conjunction with opioids. Widely used for short procedures. May produce cardiorespiratory depression, and may accumulate in impaired hepatic/renal function and after prolonged administration. Tachyphylaxis may also occur. Verbal contact with the patient may be impaired. Flumazenil may be used to reverse over-sedation. Commonly used drugs:

benzodiazepines: often used in conjunction with opioids. Widely used for short procedures. May produce cardiorespiratory depression, and may accumulate in impaired hepatic/renal function and after prolonged administration. Tachyphylaxis may also occur. Verbal contact with the patient may be impaired. Flumazenil may be used to reverse over-sedation. Commonly used drugs:

– diazepam 2.5–10 mg boluses. It and its metabolites have long duration of action.

– midazolam 2–5 mg boluses (50–200 µg/kg/h infusion).

– ketamine 5–10 mg boluses (1–2 mg/kg/h infusion). Used during regional anaesthesia, but rarely used in ICU except in asthma.

– thiopental 1–3 mg/kg/h; mainly used in neurological disease (e.g. status epilepticus). Recovery may be prolonged.

– propofol 0.3–4.0 mg/kg/h; allows rapid recovery. For patient-controlled sedation: boluses of 10–20 mg with no background infusion and a lockout of 2–5 min. Target-controlled infusion (TCI) is also used: 0.5–3.0 µg/ml target with or without patient-controlled increases as required. Propofol is licensed for 3 days’ sedation of adults (but should be avoided in children). It is licensed for longer use in neurosurgical patients. May cause propofol infusion syndrome.

– etomidate: no longer used in ICU because of adrenal suppression.

inhalational anaesthetic agents:

inhalational anaesthetic agents:

– N2O up to 70% is commonly used during regional anaesthesia, but haematological side effects preclude prolonged or frequent use.

– isoflurane has been used on ICU with good results, although high plasma levels of fluoride ions have been reported after prolonged use. May be administered using highly efficient delivery devices without the need for anaesthetic machines.

– clonidine and dexmedetomidine have been used successfully for the sedation of patients on ICU.

– clomethiazole, droperidol, chlorpromazine; rarely used. Chloral hydrate, 30–50 mg orally/rectally repeated as required, may be useful in children.

Neuromuscular blocking drugs are sometimes used in ICU to facilitate IPPV, especially if chest compliance is reduced or ICP is raised. Their use has declined in recent years because of the risk of paralysis with concurrent inadequate sedation, increased risk from accidental disconnection, possible increased incidence of DVT, PE, critical illness polyneuropathy and impaired communication. Atracurium and vecuronium are most commonly used.

NSAIDs and regional techniques may also be used to provide analgesia in ICU.

Patel SB, Kress JP (2012). Am J Respir Crit Care Med; 185: 486–97

Sedation scoring systems. Used in intensive care to assess the level of sedation of patients in order to balance its beneficial (reduced stress, cardiovascular stability, ventilator synchrony) and adverse (increased risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis) effects. Provide an opportunity to titrate the level of sedation against predefined end-points (e.g. assessments of consciousness, agitation and/or ventilator synchrony). Other parameters assessed include pain, anxiety, muscle tone and reaction to tracheal suction. Most systems use single numerical scores:

[Michael AE Ramsay, US anaesthetist]

De Jonghe B, Cook D, Appere-De-Vecchi C, et al (2000). Intensive Care Med; 26: 275–85

Seebeck effect, see Temperature measurement

Seldinger technique. Method for percutaneous cannulation of a blood vessel, described in 1953. A needle is inserted into the vessel, and a guide-wire passed through it. After removal of the needle, the cannula is introduced into the vessel over the wire, which is then removed. Refinements include the use of a dilator passed over the wire to enlarge the hole made by the needle, before the cannula is inserted. Widely used for central venous cannulation; favoured by many as being safer and more reliable than using cannula-over-needle techniques, although more costly.

Also used to cannulate other body cavities, e.g. the trachea in percutaneous tracheostomy formation, the chest for insertion of a chest drain or the abdominal cavity in paracentesis.

Selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD; Selective parenteral and enteral antisepsis regimen, SPEAR). Technique for preventing infections in patients requiring ventilatory support on ICU. SDD aims to prevent colonisation of the GIT by potentially pathogenic organisms, based on the premise that most infections on ICU are endogenous.

Non-absorbable antibacterial drugs (e.g. tobramycin, colistin, amphotericin, neomycin) are administered to the pharynx/mouth/upper GIT, whilst another (e.g. cefotaxime) is administered iv. Sparing of the normal anaerobic GIT organisms prevents overgrowth by pathogens. SDD significantly reduces nosocomial pneumonia, with some evidence of mortality benefit; however, concerns over inducing antibiotic resistance have not been fully addressed. Its place in ICU continues to be debated.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Antidepressant drugs, introduced in 1987 and increasingly replacing tricyclic antidepressant drugs as the main group of drugs used in depression and other disorders. Inhibit the presynaptic reuptake of 5-HT in the CNS, leading to an increase in 5-HT activity. Include citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine and sertraline; they have similar actions and are metabolised in the liver with half-lives of about a day (4–6 days for fluoxetine).

Have fewer side effects than tricyclic antidepressants since muscarinic, dopamine, histamine and noradrenergic receptors are unaffected. However, GIT upset, insomnia and agitation may occur; the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone and impaired platelet function have been reported. In overdose, severe adverse effects are uncommon, although the serotonin syndrome may occur if tricyclics or monoamine oxidase inhibitors are also taken.

May cause hepatic enzyme inhibition (by competing with other drugs for the same metabolic pathways), thus increasing the action of certain tricyclics, type Ic antiarrhythmic drugs (especially lipid-soluble β-adrenergic receptor antagonists), phenytoin and benzodiazepines. Increased bleeding may occur in warfarin therapy. Concurrent administration of drugs which have 5-HT reuptake blocking effects (e.g. pethidine) may provoke the serotonin syndrome.

Self-inflating bags. Rubber or silicone bags used for IPPV, which reinflate when released after compression. Thus may be used for IPPV without requiring an external gas supply, e.g. during draw-over anaesthesia, transfer of ventilated patients or CPR. May be thick-walled or lined with foam rubber. Usually assembled with a non-rebreathing valve at the outlet and a one-way valve at the inlet; thus fresh air is drawn in during refilling. O2 may be added through a port at the inlet; a reservoir bag may also be added to the inlet to increase FIO2. Available in adult and paediatric sizes. Bellows may be used in a similar way, but are less convenient to use.

Sellick’s manoeuvre, see Cricoid pressure

Semon’s law, see Laryngeal nerves

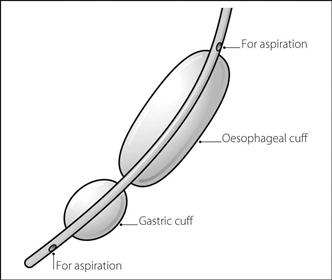

Sengstaken–Blakemore tube. Double-cuffed gastric tube designed to compress gastro-oesophageal varices, thereby controlling bleeding. Passed via the mouth into the stomach; the distal balloon is then inflated with 150–250 ml air, preventing accidental removal. The proximal balloon is then inflated to 30–40 mmHg (4–5 kPa), compressing the varices. Traction has been advocated but is rarely used. Newer versions include channels for aspiration of gastric and oesophageal contents (Fig. 138); the latter may be aspirated continuously to reduce pulmonary soiling. Thus four lumina may be present:

[Robert W Sengstaken and Arthur H Blakemore (1879–1970), US surgeons]

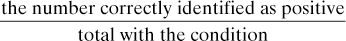

Sensitivity. In statistics, the ability of a test to exclude false negatives. Equals:

Sensory evoked potentials, see Evoked potentials

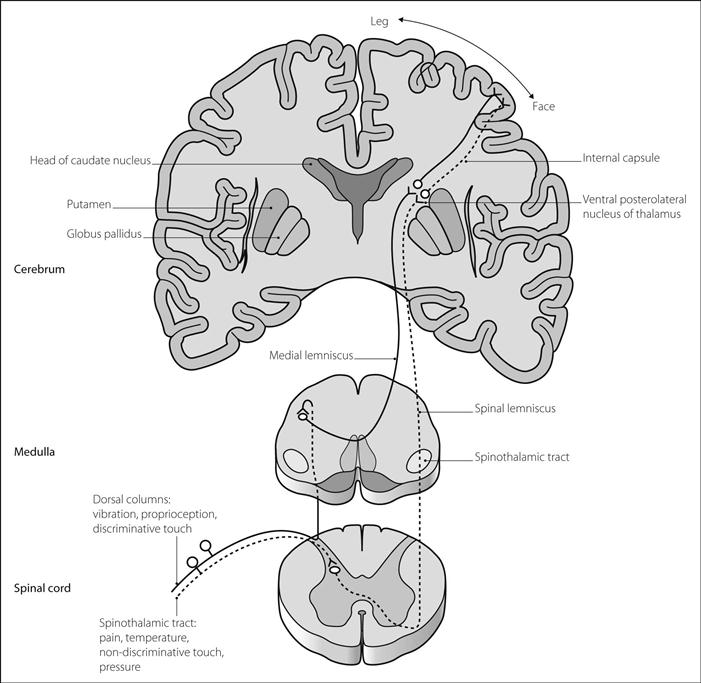

Sensory pathways. The sensory system includes the special senses, visceral sensation and general somatic sensation. The latter is divided into:

exteroreceptive sensation: provides information about the external environment and includes modalities such as touch, pressure, temperature and pain.

exteroreceptive sensation: provides information about the external environment and includes modalities such as touch, pressure, temperature and pain.

proprioceptive sensation: provides information about body position and movement.

proprioceptive sensation: provides information about body position and movement.

Free nerve endings may be associated with nociception. Some nerve endings are ‘specialised’, e.g. Meissner’s corpuscles (touch), Pacinian corpuscles (vibration and joint position) and Ruffini corpuscles (joint position). The last two may be involved with muscle spindles.

• The sensory fibres enter the spinal cord through the dorsal root, their cell bodies lying in the dorsal root ganglia. Subsequent pathways (Fig. 139):

– first-order neurones turn medially and ascend in the ipsilateral posterior columns (the fasciculus gracilis and cuneatus) to the lower medulla, where they synapse with cells in the cuneate or gracile nuclei.

– second-order neurones cross (decussate) to the contralateral side of the medulla and ascend in the medial lemniscus to the ventral posterior nucleus of the thalamus.

– third-order neurones project to the somatosensory cortex.

– third-order neurones project to the somatosensory cortex.

Fig. 139 Anatomy of sensory pathways

• Signs of sensory pathway loss:

posterior root lesion: pain and paraesthesia are experienced in the dermatomal distribution. If the root involves a reflex arc, the reflex will be diminished or lost.

posterior root lesion: pain and paraesthesia are experienced in the dermatomal distribution. If the root involves a reflex arc, the reflex will be diminished or lost.

spinothalamic tract lesion: contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation.

spinothalamic tract lesion: contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation.

brainstem and thalamus lesions: upper brainstem or thalamic lesions may cause complete hemisensory disturbance with loss of postural sense, light touch and pain sensation. ‘Pure’ thalamic lesions may result in central pain.

brainstem and thalamus lesions: upper brainstem or thalamic lesions may cause complete hemisensory disturbance with loss of postural sense, light touch and pain sensation. ‘Pure’ thalamic lesions may result in central pain.

Sepsis. SIRS as a result of proven or suspected infection (i.e. invasion of normally sterile host tissue by micro-organisms and the inflammatory response to their presence). ‘Severe sepsis’ is defined as sepsis plus organ dysfunction, hypoperfusion or hypotension, and replaces the now obsolete term septicaemia (bacteraemia is the presence of viable circulating bacteria). A major cause of organ failure in ICU, severe sepsis is directly or indirectly responsible for 75% of all ICU deaths.

Most ICU infections are endogenous, caused by colonisation of the patient’s GIT by pathogenic organisms. Gram-negative bacteria (e.g. Escherichia coli, klebsiella, pseudomonas and proteus species) have traditionally been most commonly responsible, because of their widespread presence, their tendency to acquire resistance to antibacterial drugs and their resistance to drying and disinfecting agents. Gram-positive bacteria (e.g. streptococci, staphylococci) are increasingly common, especially associated with invasive cannulation; other organisms (e.g. fungi) may also be responsible. The inflammatory response involves cytokines, nitric oxide, thromboxanes, leukotrienes, platelet activating factor, prostaglandins and complement. Endothelial and neutrophil adhesion molecule expression increases, resulting in cellular infiltration into the tissues.

• Critically ill patients are susceptible to sepsis because of:

impaired local defences, e.g. anatomical barriers, ciliary activity, coughing, gastric pH. Tracheal tubes, indwelling catheters and cannulae provide routes for infection.

impaired local defences, e.g. anatomical barriers, ciliary activity, coughing, gastric pH. Tracheal tubes, indwelling catheters and cannulae provide routes for infection.

impaired immunity. Contributory factors include drugs, malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, old age, malignancy, organ failure and infection itself. Infection control is important in reducing sepsis in the ICU.

impaired immunity. Contributory factors include drugs, malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, old age, malignancy, organ failure and infection itself. Infection control is important in reducing sepsis in the ICU.

supportive, e.g. iv fluids, O2 therapy, inotropic drugs. Current recommendations in severe sepsis are for haemodynamic resuscitation to be guided by specific goals, including:

supportive, e.g. iv fluids, O2 therapy, inotropic drugs. Current recommendations in severe sepsis are for haemodynamic resuscitation to be guided by specific goals, including:

– CVP 8–12 mmHg; MAP 65–90 mmHg.

– central venous oxygen saturation > 70%.

early use of antibacterial and/or antifungal drugs. Initial choice is based on the most likely infective organisms. Samples of urine, sputum, blood and CSF should be taken before starting therapy.

early use of antibacterial and/or antifungal drugs. Initial choice is based on the most likely infective organisms. Samples of urine, sputum, blood and CSF should be taken before starting therapy.

source control: e.g. surgical drainage, debridement, removal of infected lines and catheters.

source control: e.g. surgical drainage, debridement, removal of infected lines and catheters.

use of corticosteroids is controversial (see Septic shock).

use of corticosteroids is controversial (see Septic shock).

activated protein C is no longer recommended in severe sepsis.

activated protein C is no longer recommended in severe sepsis.

new immunomodulatory treatments (e.g. anti-endotoxin antibodies, anti-cytokine products) have been investigated, with disappointing clinical results. This may represent the heterogeneous patient population and/or the complex pathophysiology of sepsis.

new immunomodulatory treatments (e.g. anti-endotoxin antibodies, anti-cytokine products) have been investigated, with disappointing clinical results. This may represent the heterogeneous patient population and/or the complex pathophysiology of sepsis.

nutrition is important as hypercatabolism is common.

nutrition is important as hypercatabolism is common.

evidence-based care bundles have been developed to support timely and effective management.

evidence-based care bundles have been developed to support timely and effective management.

Complications include septic shock and multiple organ failure, including acute lung injury, acute kidney injury, hepatic failure, pancreatitis and diabetes mellitus, DIC, cardiac failure and coma. GIT haemorrhage is common; prophylaxis includes proton pump inhibitors and H2 receptor antagonists.

Eissa D, Carton EG, Buggy DJ (2010). Br J Anaesth; 105: 734–43

See also, Catheter-related sepsis; Fungal infection in the ICU; Nosocomial infection; Sepsis-related organ failure assessment; Sepsis score; Sepsis severity score

Sepsis-related organ failure assessment (SOFA). Scoring system devised in 1994 to describe quantitatively and objectively the degree of organ dysfunction in sepsis over time. Intended to improve the understanding of organ dysfunction/failure and to assess the effect of particular therapies on its progression. The function of six different organ systems (respiratory, cardiovascular, central nervous, coagulation, hepatic and renal systems) is weighted (each scored 1–4) according to the degree of physiological derangement observed. Minimum SOFA score is 6; maximum 24.

Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al (1996). Intensive Care Med; 22: 707–10

Sepsis score. Index of severity of sepsis, devised in 1983; assigns scores according to local infection, pyrexia, systemic response and laboratory results. Now rarely used.

Sepsis severity score. Index of severity of sepsis, devised in 1983 by assigning scores of 1–5 according to the degree of impairment of each of the following organ systems: lung, kidney, coagulation, CVS, liver, GIT and neurological. The three highest (worst) scores are then squared to produce the final score.

Sepsis syndrome. Obsolete term for the systemic response to infection.

See also, Sepsis; Septic shock; Septicaemia; Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Septic shock. Hypotension (or the requirement for inotropic or vasopressor drugs) despite adequate fluid resuscitation, with evidence of perfusion abnormalities (e.g. lactic acidosis, oliguria), associated with sepsis. Initial features include hyperthermia, tachycardia, tachypnoea, hypotension and vasodilatation with a hyperdynamic circulation and increased cardiac output. In later stages, or if hypovolaemia or poor myocardial function is present, hypotension with vasoconstriction supervenes. Mortality is about 50%, although it varies with patients’ characteristics and the nature of the sepsis. Most cases are caused by bacteria (approximately equally split between Gram-positive and -negative, although traditionally associated with Gram-negative organisms); other organisms may also be responsible.

Risk factors include: age (< 10 years and > 70 years); diabetes mellitus; alcoholic liver disease; ischaemic heart disease; malignancy; immunosuppression; prolonged hospital stay; invasive monitoring; tracheal intubation; and prior use of antibacterial agents. The underlying pathophysiology is as for sepsis; microvascular abnormalities supervene, including impaired autoregulation, altered blood cell morphology, increased endothelial permeability and opening of arteriovenous shunts.

• Cardiovascular features include:

reduced SVR with relative hypovolaemia.

reduced SVR with relative hypovolaemia.

increased pulmonary vascular resistance.

increased pulmonary vascular resistance.

increased capillary permeability.

increased capillary permeability.

reduced myocardial contractility caused by circulating depressant factors, acidaemia and hypoxaemia.

reduced myocardial contractility caused by circulating depressant factors, acidaemia and hypoxaemia.

O2 consumption may be normal but O2 extraction and utilisation are reduced.

O2 consumption may be normal but O2 extraction and utilisation are reduced.

high-dose corticosteroids are associated with increased mortality; however recent evidence suggests that at lower doses (e.g. hydrocortisone 200 mg/day) they may reduce vasopressor requirements and speed resolution of shock (by increasing the sensitivity of α-adrenergic receptors on vascular smooth muscle). A corticotropin (Synacthen) stimulation test was previously advocated to identify patients with impaired pituitary–adrenal axis function; this is no longer considered necessary for identifying patients who may benefit from steroid therapy. Survival benefits are unclear and steroid use remains controversial; however, in extremely sick patients with high vasopressor requirements, many advocate administering a therapeutic trial with cessation if there is no clinical improvement.

high-dose corticosteroids are associated with increased mortality; however recent evidence suggests that at lower doses (e.g. hydrocortisone 200 mg/day) they may reduce vasopressor requirements and speed resolution of shock (by increasing the sensitivity of α-adrenergic receptors on vascular smooth muscle). A corticotropin (Synacthen) stimulation test was previously advocated to identify patients with impaired pituitary–adrenal axis function; this is no longer considered necessary for identifying patients who may benefit from steroid therapy. Survival benefits are unclear and steroid use remains controversial; however, in extremely sick patients with high vasopressor requirements, many advocate administering a therapeutic trial with cessation if there is no clinical improvement.

Eissa D, Carton EG, Buggy DJ (2010). Br J Anaesth; 105: 734–43

Sequential analysis, see Statistical tests

Serotonin, see 5-Hydroxytryptamine

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors, see Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Serotonin syndrome. Impaired mental state, increased muscle activity and autonomic instability arising from excessive 5-HT activity in the brainstem and spinal cord. Seen in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) overdose, especially in combination with other antidepressant drugs (especially monoamine oxidase inhibitors). Has also been reported after intraoperative use of methylene blue (a potent inhibitor of monoamine oxidase) in a patient taking SSRIs. Also associated with the use of tramadol, pethidine and cocaine. Features include confusion, agitation, convulsions, myoclonus, rigidity, hyperreflexia, fever, diarrhoea, hyper- or hypotension and tachycardia. DIC, renal and cardiac failure may also occur. Treatment is supportive; 5-HT antagonists, e.g. methysergide, cyproheptadine, have been used. Usually lasts for < 24 h but deaths have been reported.

A washout period of several weeks has been suggested between monoamine oxidase inhibitor and SSRI therapy.

ribavirin 8 mg/kg iv tds (N.B. not licensed for this use in UK) or 1.2 g orally bd after a loading dose of 4 g orally, for 7–14 days (caution in impaired renal function).

ribavirin 8 mg/kg iv tds (N.B. not licensed for this use in UK) or 1.2 g orally bd after a loading dose of 4 g orally, for 7–14 days (caution in impaired renal function).

hydrocortisone 2–4 mg/kg iv tds/qds, for ~7 days. Methylprednisolone 10 mg/kg/day iv has been used for 2 days before hydrocortisone.

hydrocortisone 2–4 mg/kg iv tds/qds, for ~7 days. Methylprednisolone 10 mg/kg/day iv has been used for 2 days before hydrocortisone.

Severinghaus electrode, see Carbon dioxide measurement

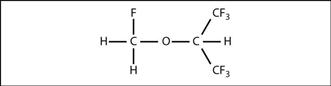

Sevoflurane. 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoroisopropyl fluoromethyl ether (Fig. 140). Inhalational anaesthetic agent, first synthesised in 1968 but not introduced in the UK until 1995 because of the development of isoflurane in preference.

colourless liquid with pleasant smelling vapour, 7.5 times heavier than air.

colourless liquid with pleasant smelling vapour, 7.5 times heavier than air.

SVP at 20°C 21 kPa (160 mmHg).

SVP at 20°C 21 kPa (160 mmHg).

MAC 1.4% (80 years) – 2.5% (children/young adults); up to 3.3% in neonates.

MAC 1.4% (80 years) – 2.5% (children/young adults); up to 3.3% in neonates.

supplied in liquid form with no additive.

supplied in liquid form with no additive.

interacts with soda lime at temperature of 65°C to produce Compounds A, B, C, D and E, the first two the only ones produced in clinical practice. Production is more likely at high temperatures, high concentrations of sevoflurane, use of baralyme and low gas flows. Compound A (pentafluoroisopropenyl fluoromethyl ether) is no longer thought to be significant, despite its toxicity in rats at high dosage; clinical experience has never implicated it in causing harm in humans, even with sevoflurane at low fresh gas flows (maximal concentrations of Compound A around 30 ppm; minimal levels for human toxicity thought to be around 150–200 ppm).

interacts with soda lime at temperature of 65°C to produce Compounds A, B, C, D and E, the first two the only ones produced in clinical practice. Production is more likely at high temperatures, high concentrations of sevoflurane, use of baralyme and low gas flows. Compound A (pentafluoroisopropenyl fluoromethyl ether) is no longer thought to be significant, despite its toxicity in rats at high dosage; clinical experience has never implicated it in causing harm in humans, even with sevoflurane at low fresh gas flows (maximal concentrations of Compound A around 30 ppm; minimal levels for human toxicity thought to be around 150–200 ppm).

• Effects:

– smooth, extremely rapid induction and recovery. Concentrations of 4–8% produce anaesthesia within a few vital capacity breaths. Early postoperative analgesia may be required as emergence is so rapid.

– increases the risk of emergence agitation, compared with isoflurane, in children < 5 years.

– anticonvulsant properties as for isoflurane.

– at concentration of < 1 MAC has minimal effect on ICP in patients with normal ICP. Studies suggest that autoregulation is preserved in patients with cerebrovascular disease, in contrast to other inhalational agents.

– reduces CMRO2 as for isoflurane, with about a 50% reduction at 2 MAC.

– decreases intraocular pressure.

– has poor analgesic properties.

– well-tolerated vapour with minimal airway irritation.

– respiratory depressant, with increased rate and decreased tidal volume.

– myocardial O2 demand decreases.

– arrhythmias uncommon, as for isoflurane. Little myocardial sensitisation to catecholamines.

– renal and hepatic blood flow generally preserved.

– dose-dependent uterine relaxation.

– nausea/vomiting occurs in up to 25% of cases.

– skeletal muscle relaxation; non-depolarising neuromuscular blockade may be potentiated.

Under 5% metabolised in the liver to hexafluoroisopropanol and inorganic fluoride ions, the rest being excreted by the lungs. High levels of fluoride have never been reported, even after prolonged surgery, but avoidance in renal impairment has been suggested. Inducers of the particular cytochrome P450 enzyme involved (e.g. isoniazid, alcohol) increase metabolism of sevoflurane, but barbiturates do not.

0.5–3.0% is usually adequate for maintenance of anaesthesia, with higher concentrations for induction. Tracheal intubation may be performed easily with spontaneous respiration. Considered the agent of choice for inhalational induction in paediatrics because of its rapid and smooth induction characteristics. Has also been used for the difficult airway, including airway obstruction.

Fig. 140 Structure of sevoflurane

Shivering, postoperative. Tremors were first described after barbiturate administration, but they may occur following all types of general anaesthesia. Traditionally said to be more common following halothane (‘halothane shakes’). Rarer in elderly patients due to decreased thermoregulatory control. May increase metabolic rate by up to six times and triple O2 consumption. Can also aggravate postoperative pain, damage surgical wounds and increase intraocular and intracranial pressures. Damage to teeth may occur, especially in the presence of an oral airway.

EMG studies suggest that postoperative shivering differs from shivering due to cold. It has been suggested that anaesthetic agents suppress descending pathways which normally inhibit spinal reflexes; this may be more likely than a response to intraoperative hypothermia, although the latter may be of importance if severe.

fentanyl 25 µg iv or pethidine 10–25 mg iv may be effective. Pentazocine 30 mg or doxapram 1 mg/kg or pre-induction ondansetron has also been used.

fentanyl 25 µg iv or pethidine 10–25 mg iv may be effective. Pentazocine 30 mg or doxapram 1 mg/kg or pre-induction ondansetron has also been used.

Shivering after epidural anaesthesia is common, and is thought to be caused by differential nerve blockade, either suppressing descending inhibition of spinal reflexes or allowing selective transmission of cold sensation. Shivering is rare in spinal anaesthesia, where blockade is more dense. Warming of epidural injectate has produced conflicting results. Epidural administration of opioid analgesic drugs, e.g. sufentanil 50 µg, fentanyl 25 µg, pethidine 25 mg, may be an effective remedy.

Shock. Syndrome, originally described by Crile, in which tissue perfusion is inadequate for the tissues’ metabolic requirements. Sympathetic compensatory mechanisms may preserve organ perfusion initially, but subsequent organ dysfunction may lead to irreversible organ damage and death.

hypovolaemic shock, e.g. following haemorrhage, burns, dehydration.

hypovolaemic shock, e.g. following haemorrhage, burns, dehydration.

cardiogenic shock, e.g. following MI.

cardiogenic shock, e.g. following MI.

others, e.g. anaphylaxis, adrenocortical insufficiency, neurogenic shock (e.g. in high spinal cord injury).

others, e.g. anaphylaxis, adrenocortical insufficiency, neurogenic shock (e.g. in high spinal cord injury).

Division into hypovolaemia, myocardial failure and peripheral vascular failure has been suggested as being more indicative of underlying mechanisms. Thus shock may arise from inadequate cardiac output or maldistribution of blood flow; the latter has been increasingly implicated by studies of O2 delivery ( ) and total body O2 consumption (

) and total body O2 consumption ( ). A decrease in

). A decrease in  is thought to represent maldistribution rather than an absolute decrease in blood flow. In cardiogenic shock both

is thought to represent maldistribution rather than an absolute decrease in blood flow. In cardiogenic shock both  and cardiac output are reduced; in septic shock they may both increase initially. Features depend on the aetiology but include hypotension, tachycardia, oliguria and metabolic acidosis. MODS may follow, with acute kidney injury and ARDS. Hepatic, gastrointestinal and pancreatic impairment, and DIC may occur.

and cardiac output are reduced; in septic shock they may both increase initially. Features depend on the aetiology but include hypotension, tachycardia, oliguria and metabolic acidosis. MODS may follow, with acute kidney injury and ARDS. Hepatic, gastrointestinal and pancreatic impairment, and DIC may occur.

directed at the primary cause.

directed at the primary cause.

cardiovascular support: achieved with iv fluids, blood products, inotropic drugs and vasodilator drugs. Haemodynamic monitoring consists of measurement of BP, pulse rate, CVP, urine output, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and cardiac output. Lactate and central venous oxygen saturations are also measured.

cardiovascular support: achieved with iv fluids, blood products, inotropic drugs and vasodilator drugs. Haemodynamic monitoring consists of measurement of BP, pulse rate, CVP, urine output, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and cardiac output. Lactate and central venous oxygen saturations are also measured.  ,

,  and gastric tonometry have previously been used to guide therapy.

and gastric tonometry have previously been used to guide therapy.

Shock index (SI). Ratio of heart rate to systolic blood pressure; has been used to identify and monitor haemorrhage in trauma patients. An elevated shock index (> 0.9) has been suggested as an indication for admission to ICU.

Shock lung, see Acute respiratory distress syndrome

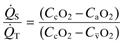

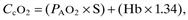

Shunt. One extreme form of  mismatch, causing hypoxaemia. Refers to the actual amount of venous blood bypassing ventilated alveoli and mixing with pulmonary end-capillary blood (cf. venous admixture, the calculated amount of shunt required to produce the observed arterial PO2).

mismatch, causing hypoxaemia. Refers to the actual amount of venous blood bypassing ventilated alveoli and mixing with pulmonary end-capillary blood (cf. venous admixture, the calculated amount of shunt required to produce the observed arterial PO2).

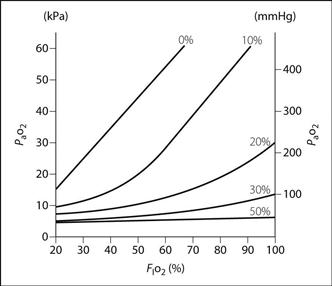

Hypoxaemia due to shunt responds poorly to increased FIO2, since the O2 content of pulmonary end-capillary blood is already near maximum, because of the shape of the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve. Some benefit is derived from increased dissolved O2. Thus the amount of shunt may be estimated from the response to breathing high concentrations of O2, assuming a haemoglobin concentration of 10–14 g/100 ml, arterial PCO2 of 3.3–5.3 kPa (25–40 mmHg) and arteriovenous O2 difference of 5 ml/100 ml (Fig. 141). Amount of shunt may also be estimated from the shunt equation.

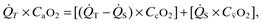

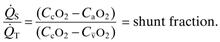

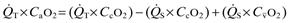

Allows calculation of shunt. Derived as follows. Total pulmonary blood flow equals  , made up of blood flow to unventilated alveoli (

, made up of blood flow to unventilated alveoli ( ) and blood flow to ventilated alveoli (

) and blood flow to ventilated alveoli ( ; Fig. 142).

; Fig. 142).

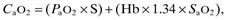

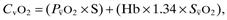

Arterial and venous O2 contents may be estimated thus:

where PaO2 and SaO2 = arterial PO2 and haemoglobin saturation respectively,

and

and  = mixed venous PO2 and haemoglobin saturation respectively,

= mixed venous PO2 and haemoglobin saturation respectively,

S = volume of O2 dissolved in 100 ml blood per kPa applied O2 tension (0.0225) or mmHg (0.003),

Hb = haemoglobin content in g/100 ml,

End-capillary O2 content cannot be measured directly, but is estimated from calculation of the alveolar air equation:

where PAO2 = ‘ideal’ alveolar PO2, and saturation is assumed to be 100%.

Fig. 142 Calculation of shunt equation

Shunt procedures. Performed to provide access to the circulation for haemodialysis and related procedures, thus requiring the capacity for high flow rates of blood both out of and back into the circulation. May involve:

temporary cannulation of vessel(s), e.g. central venous cannulation with a double-lumen catheter (or two single ones). Choice of vessel and technique is as for placement of any central line, although the catheter is usually required for a longer time. Venous stenosis or thrombosis may be more common if the subclavian vein is used. Most double-lumen dialysis catheters are designed with one channel for withdrawal and one for return of blood; the latter opens proximal to the former to reduce the withdrawal of freshly dialysed blood from the return channel via the withdrawal channel, and thus inefficiency.

temporary cannulation of vessel(s), e.g. central venous cannulation with a double-lumen catheter (or two single ones). Choice of vessel and technique is as for placement of any central line, although the catheter is usually required for a longer time. Venous stenosis or thrombosis may be more common if the subclavian vein is used. Most double-lumen dialysis catheters are designed with one channel for withdrawal and one for return of blood; the latter opens proximal to the former to reduce the withdrawal of freshly dialysed blood from the return channel via the withdrawal channel, and thus inefficiency.

surgical creation of a permanent arteriovenous shunt between adjacent vessels, e.g. radial artery/cephalic vein, using either direct anastomosis of the vessels (fistula) or insertion of a Silastic catheter (Scribner shunt). Venous wall thickening allows repeated cannulation, although thrombosis and venous stenosis may occur. Other complications include infection, pseudoaneurysm and arm ischaemia. Surgical shunts may be performed under local infiltration anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia (e.g. brachial plexus block) or general anaesthesia. Anaesthetic considerations are as for renal failure.

surgical creation of a permanent arteriovenous shunt between adjacent vessels, e.g. radial artery/cephalic vein, using either direct anastomosis of the vessels (fistula) or insertion of a Silastic catheter (Scribner shunt). Venous wall thickening allows repeated cannulation, although thrombosis and venous stenosis may occur. Other complications include infection, pseudoaneurysm and arm ischaemia. Surgical shunts may be performed under local infiltration anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia (e.g. brachial plexus block) or general anaesthesia. Anaesthetic considerations are as for renal failure.

Shy–Drager syndrome, see Autonomic neuropathy

Siamese twins, see Conjoined twins

Sick Doctor Scheme. Scheme set up in 1981 in the UK by the Association of Anaesthetists and Royal College of Psychiatrists, to encourage voluntary reporting of sick doctors practising anaesthesia. The anonymous reporter, having contacted the Association, is given the name and telephone number of a referee. The latter contacts an appointed psychiatrist from another region, who in turn contacts the sick doctor. A similar scheme (National Counselling Service for Sick Doctors) is now available to doctors from all specialties. Intended as an alternative to the more formal scheme available via the Department of Health (previously involving appropriate action taken via a subcommittee [‘three wise men’ procedure]; more recently replaced by a framework involving the National Clinical Assessment Service) and General Medical Council (assesses doctors on health and performance as well as conduct).

A scheme of the same name exists in Ireland, to help doctors affected by substance abuse.

Sick euthyroid syndrome (Non-thyroidal illness syndrome). Abnormal thyroid function tests occurring in critically ill patients. The most common pattern is low triiodothyronine (T3) with normal or raised thyroxine (T4) and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH). Low T3 and T4 are generally associated with more severe critical illness and worse prognosis. Most patients are clinically euthyroid. Thought to result from impaired pulsatile secretion of TSH, reduced peripheral conversion of T4 to T3 and reduced plasma protein binding.

Bello G, Ceaichisciuc I, Silva S, Antonelli M (2010). Minerva Anestesiol; 76: 919–28

Sick sinus syndrome. Syndrome caused by impaired sinoatrial node activity or conduction; may lead to periods of severe bradycardia with intermittent loss of P waves or sinus arrest, and may alternate with periods of SVT or AF (bradycardia–tachycardia syndrome; bradytachy syndrome). Although it usually occurs in elderly patients with ischaemic heart disease, it is also a major cause of sudden death in children and young adults. May be precipitated by anaesthesia and result in refractory bradycardia or even asystole. Requires cardiac pacing if diagnosed preoperatively or if it occurs perioperatively.

Staikou C, Chondrogiannis K, Mani A (2012). Br J Anaesth; 108: 730–44

Sickle cell anaemia. Haemoglobinopathy, first described in 1910 in Chicago. Caused by substitution of glutamic acid by valine in the sixth amino acid from the N-terminal of haemoglobin β chains. Inherited as an autosomal gene; heterozygotes (genotype HbAS; sickle cell trait) possess both normal (HbA) and abnormal (HbS) haemoglobins (though they may also possess other abnormal haemoglobin combinations [e.g. HbSC]) or β thalassaemia (Sβ); homozygotes (HbSS) possess only abnormal haemoglobin. Thought to have originated from spontaneous genetic mutation, with subsequent selection owing to the relative resistance against falciparum malaria conferred by sickle cell trait. Most common in West Central Africa, North-East Saudi Arabia and East Central India, but has been described in Southern Mediterranean populations. Incidence of HbSS in US Blacks is < 1%; incidence of HbAS is 8–10%.

Deoxygenated HbS polymerises and precipitates within red blood cells, with distortion and increased rigidity. Sickle-shaped red cells are characteristic. The distorted cells increase blood viscosity, impair blood flow and cause capillary and venous thrombosis and organ infarction. They have shortened survival time. O2 affinity of dissolved HbS is normal, but overall affinity is reduced if some of the HbS is polymerised. HbS polymerises at PO2 of 5–6 kPa (40–50 mmHg); thus HbSS patients are continuously sickling. HbAS patients’ red cells contain both HbS and HbA and sickle at 2.5–4.0 kPa (20–30 mmHg).

– haemolysis causing anaemia and hyperbilirubinaemia. Gallstones may occur. Enlargement of the skull and long bones is common, due to compensatory bone marrow hyperplasia. Acute aplastic crises may occur, and sequestration crises in children.

– impaired tissue blood flow may result in CVA, papillary necrosis of the kidney, ulcers, pulmonary infarcts, priapism and avascular necrosis of bone. Crises are caused by acute vascular occlusion, and may feature neurological lesions and severe pain, e.g. abdominal, back, chest (the sickle chest syndrome is a common cause of death and includes cough, fever and severe hypoxaemia). They may be precipitated by hypothermia, dehydration, infection, exertion and hypoxaemia. Treatment is with analgesia (often requiring opioids, e.g. by PCA), O2 and rehydration. Exchange blood transfusion may be required.

Sickle cells are usually present in peripheral blood in HbSS.

– preoperative assessment is directed towards the above complications, especially impairment of pulmonary and renal function. Preoperative folic acid has been suggested. Exchange transfusion is often used in HbSS patients before major surgery, aiming to reduce HbS concentrations to < 30%. A less aggressive transfusion strategy is to aim for a haematocrit of > 30%; both approaches have similar efficacy.

– hypoxaemia, dehydration, hypothermia and acidosis should be prevented at all times perioperatively. Prophylactic antibiotics are often administered.

– standard techniques may be used, apart from tourniquets which cause tissue ischaemia (IVRA is contraindicated). Heat loss should be prevented and cardiovascular stability maintained. Preoxygenation and FIO2 of 50% reduces the risk of hypoxaemia by increasing arterial PO2 and pulmonary O2 reserve. IV hydration should be maintained. Frequent analysis of acid–base status is required in HbSS patients. Prophylactic bicarbonate administration has been suggested, but administration according to acid–base analysis is usually preferred.

postoperatively: the precautions already instituted should continue, since complications may occur postoperatively. Patients are generally considered unsuitable for most day-case surgery. O2 administration for at least 24 h is usually advocated.

postoperatively: the precautions already instituted should continue, since complications may occur postoperatively. Patients are generally considered unsuitable for most day-case surgery. O2 administration for at least 24 h is usually advocated.

SID, see Strong ion difference

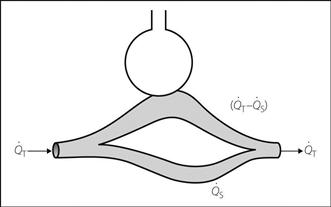

Siggaard-Andersen nomogram. Diagram derived from analysis of many blood samples, showing the plot of log arterial PCO2 against plasma pH, with base excess, standard bicarbonate and buffer base illustrated as additional lines (Fig. 143). Allows determination of arterial PCO2 by equilibrating a blood sample with two known concentrations of CO2, and measuring the sample pH at each concentration. The points are plotted on the diagram and joined by a line, and the PCO2 read from the vertical scale according to the pH of the original sample. Alternatively, if arterial PCO2 can be measured directly, a single measurement of pH and PCO2, together with haemoglobin concentration (since haemoglobin is a major blood buffer), allows determination of the derived data. Modern blood-gas machines automatically perform the required calculations, making such plotting unnecessary.

[Ole Siggaard-Andersen, Danish biochemist]

Fig. 143 Siggaard-Andersen nomogram

Significance, see Statistical significance

Sildenafil (Viagra). Orally active phosphodiesterase inhibitor, selective for cyclic guanine monophosphate (cGMP)-specific phosphodiesterases. Licensed for use in pulmonary hypertension and male erectile dysfunction. Catastrophic interactions with nitrates (e.g. GTN) have been reported, resulting in severe hypotension and death; thus a history must be obtained in suspected ischaemic heart disease before administering nitrates. Tadalafil and vardenafil are related drugs.

Simplified acute physiology score (SAPS). Scoring system used to assess severity of illness by determining the degree of deviation of physiological variables from normal values. Originally incorporating 14 variables and excluding pre-existing disease, a modified version (SAPS II) has been developed in which 12 variables are weighted according to age and underlying disease. SAPS III uses a new, improved model for risk adjustment. Used in a similar way to APACHE.

Capuzzo M, Moreno RP, Le Gall JR (2010). Curr Opin Crit Care; 16: 477–81

See also, Mortality/survival prediction on intensive care unit

Simpson, James Young (1811–1870). Scottish obstetrician; Professor of Midwifery at Edinburgh. The first to administer an anaesthetic for obstetrics in 1847, using diethyl ether. Following a suggestion by Waldie later that year, he used chloroform for the same purpose. Encountered stiff opposition from the clergy and others, who maintained that painful childbirth was either God’s will, beneficial to the patient, or both; this continued until Snow’s administration of chloroform to Queen Victoria in 1853 (‘chloroform à la reine’). Helped popularise chloroform as the replacement for ether. Was made baronet in 1866.

[David Waldie (1813–1889), Scottish-born Liverpool doctor and chemist]

Single-pass albumin dialysis, see Liver dialysis

Sinoatrial node, see Heart, conducting system

Sinus arrhythmia. Normal phenomenon (especially in young people) characterised by alternating periods of slow and rapid heart rates. The ECG shows sinus rhythm with irregular spacing of normal complexes. Most commonly related to respiration, with a rapid rate at end-inspiration and a slower rate at end-expiration. A number of mechanisms have been proposed, including: activation of pulmonary stretch receptors during inspiration, causing inhibition of the cardioinhibitory centre via vagal afferents; changes in intrathoracic pressure causing stretching of the sinoatrial node, producing cardiac accelerations during inspiration; and lower intrathoracic pressure during inspiration, causing reduced cardiac output, leading to an increase in heart rate mediated by the baroreceptor reflex. May also involve direct impulse conduction between medullary respiratory and cardiac neurones. Also seen in patients treated with digoxin. Abolished by atropine.

Sinus bradycardia. Usually defined as sinus rhythm at less than 60 beats/min. The ECG shows normal P waves and QRS complexes occurring at a slow rate.

physiological slowing, e.g. in athletes, or during sleep.

physiological slowing, e.g. in athletes, or during sleep.

disease states, e.g. hypothyroidism, raised ICP, acute MI, sick sinus syndrome, jaundice.

disease states, e.g. hypothyroidism, raised ICP, acute MI, sick sinus syndrome, jaundice.

activation of vagal reflexes, e.g. carotid sinus massage, Valsalva manoeuvre. During anaesthesia, it may follow skin incision, stretching or dilatation of the anus, cervix, mesentery and bladder (Brewer–Luckhardt reflex), pulling on the ocular muscles (oculocardiac reflex). May occur in critically ill patients during tracheobronchial suctioning.

activation of vagal reflexes, e.g. carotid sinus massage, Valsalva manoeuvre. During anaesthesia, it may follow skin incision, stretching or dilatation of the anus, cervix, mesentery and bladder (Brewer–Luckhardt reflex), pulling on the ocular muscles (oculocardiac reflex). May occur in critically ill patients during tracheobronchial suctioning.

hypoxaemia, especially in children. Thought to be caused by central depression of the vasomotor centre.

hypoxaemia, especially in children. Thought to be caused by central depression of the vasomotor centre.

blockade of the cardiac sympathetic innervation during high spinal or epidural anaesthesia.

blockade of the cardiac sympathetic innervation during high spinal or epidural anaesthesia.

drugs, e.g. propofol, neostigmine, digoxin, opioid analgesic drugs, β-adrenergic receptor antagonists.

drugs, e.g. propofol, neostigmine, digoxin, opioid analgesic drugs, β-adrenergic receptor antagonists.

If it occurs, the stimulus should be stopped. It may be treated with anticholinergic drugs (e.g. atropine), β-adrenergic receptor agonists or cardiac pacing, but treatment is only required if accompanied by symptoms, hypotension or escape beats.

Sinus rhythm. Normal heart rhythm in which each P wave is followed by a QRS complex on the ECG; i.e. each impulse originates in the sinoatrial node, which has the fastest inherent rhythmicity of all cardiac pacemaker cells. Normal heart rate is usually defined as 60–100 beats/min.

See also, Cardiac cycle; Heart, conducting system; Sinus arrhythmia; Sinus bradycardia; Sinus tachycardia

Sinus tachycardia. Usually defined as sinus rhythm at over 100 beats/min. The ECG shows regular normal P waves and QRS complexes at a rapid rate.

increased sympathetic activity, e.g. fear, anxiety; during anaesthesia, it may represent hypoxaemia, hypercapnia, and inadequate anaesthesia or neuromuscular blockade. It may also occur as a compensatory mechanism, e.g. in anaemia, hypovolaemia, air embolism/PE.

increased sympathetic activity, e.g. fear, anxiety; during anaesthesia, it may represent hypoxaemia, hypercapnia, and inadequate anaesthesia or neuromuscular blockade. It may also occur as a compensatory mechanism, e.g. in anaemia, hypovolaemia, air embolism/PE.

increased metabolic rate, e.g. hyperthyroidism, fever, pregnancy, MH.

increased metabolic rate, e.g. hyperthyroidism, fever, pregnancy, MH.

drugs, e.g. sevoflurane, isoflurane, pancuronium, sympathomimetic drugs, cocaine, anticholinergic drugs.

drugs, e.g. sevoflurane, isoflurane, pancuronium, sympathomimetic drugs, cocaine, anticholinergic drugs.

Reduces the time available for ventricular filling and coronary blood flow; it may precipitate myocardial ischaemia if severe. Treatment is usually directed at the cause; β-adrenergic receptor antagonists may be required if the patient is at risk of myocardial ischaemia.

Sinusitis. Infection of the nasal sinuses of the skull. May occur as a consequence of upper respiratory tract infection, trauma or, especially relevant to ICU, prolonged tracheal intubation; has been reported in 2–40% of patients requiring IPPV. Up to 10 times more common if nasotracheal or nasogastric tubes are in place; thought to be related to obstruction of drainage through the sinus ostia (although in a third of cases the contralateral side is affected). Also more common in immunosuppressed and diabetic patients. Usually affects the maxillary or sphenoid sinuses, although ethmoid and frontal sinusitis may also occur (and may result in cerebral venous thrombosis).

May present with non-specific features of sepsis; diagnosed by CT scanning (although plain X-rays may be helpful), ± antral puncture and aspiration. Ultrasound examination may be useful, but requires specialised equipment. Organisms involved are usually Gram-negative bacteria, staphylococci or anaerobes. Management includes extubation, antibacterial drugs ± surgical drainage. Antihistamines and decongestants have also been used. Usually resolves within a week of extubation.

Skin diseases. Anaesthetic considerations may be related to:

diseases with cutaneous and systemic manifestations, e.g. connective tissue diseases, porphyria, polymyositis, neurofibromatosis, severe skin disease with anaemia and malnutrition.

diseases with cutaneous and systemic manifestations, e.g. connective tissue diseases, porphyria, polymyositis, neurofibromatosis, severe skin disease with anaemia and malnutrition.

scarring or fibrosis of tissues around the face, mouth or neck causing difficulty with tracheal intubation, e.g. systemic sclerosis, epidermolysis bullosa dystrophica. In the latter, bullous lesion formation may follow instrumentation (e.g. laryngoscopy), and may be followed by scarring.

scarring or fibrosis of tissues around the face, mouth or neck causing difficulty with tracheal intubation, e.g. systemic sclerosis, epidermolysis bullosa dystrophica. In the latter, bullous lesion formation may follow instrumentation (e.g. laryngoscopy), and may be followed by scarring.

involvement of the immune system causing airway obstruction (e.g. hereditary angioedema) or severe manifestations of histamine release (e.g. urticaria pigmentosa). Histamine-releasing drugs should be avoided.

involvement of the immune system causing airway obstruction (e.g. hereditary angioedema) or severe manifestations of histamine release (e.g. urticaria pigmentosa). Histamine-releasing drugs should be avoided.

increased heat loss during anaesthesia if large areas of erythema are present.

increased heat loss during anaesthesia if large areas of erythema are present.

effect of drug therapy, e.g. corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs.

effect of drug therapy, e.g. corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs.

In addition, anaesthetic agents may precipitate cutaneous lesions (e.g. in adverse drug reactions, bullous eruption following barbiturate poisoning, porphyria).

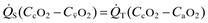

Skull. The upper part contains the brain, whilst the lower anterior portion forms the facial skeleton:

lateral aspect: consists of parietal and occipital bones posteriorly, temporal and sphenoid bones inferiorly, and frontal bone, with the zygomatic and maxillary bones below, anteriorly. The mandible articulates with the temporal bone at the temporomandibular joint.

lateral aspect: consists of parietal and occipital bones posteriorly, temporal and sphenoid bones inferiorly, and frontal bone, with the zygomatic and maxillary bones below, anteriorly. The mandible articulates with the temporal bone at the temporomandibular joint.

anterior aspect: consists of frontal bone superiorly, zygomatic bones at the inferolateral edges of the orbits, and maxilla centrally, with the mandible inferiorly. Nerves and vessels pass through the anterior foramina and the inferior and superior orbital fissures (Fig. 144a). In addition, the foramen rotundum (below and medial to the superior orbital fissure’s medial end) transmits the maxillary division of the fifth cranial nerve.

anterior aspect: consists of frontal bone superiorly, zygomatic bones at the inferolateral edges of the orbits, and maxilla centrally, with the mandible inferiorly. Nerves and vessels pass through the anterior foramina and the inferior and superior orbital fissures (Fig. 144a). In addition, the foramen rotundum (below and medial to the superior orbital fissure’s medial end) transmits the maxillary division of the fifth cranial nerve.

inferior aspect: especially important because of the structures transmitted by its foramina (Fig. 144b).

inferior aspect: especially important because of the structures transmitted by its foramina (Fig. 144b).

In addition, branches of the first cranial nerve pass through the cribriform plate’s perforations.

See also, Mandibular nerve blocks; Maxillary nerve blocks; Ophthalmic nerve blocks; Orbital cavity

Skull X-ray. Useful investigation for the detection of linear and depressed skull fractures following head injury, for classifying facial trauma and planning of maxillofacial surgery. Although the presence of a fracture increases the likelihood of intracranial damage, significant injury may be present with a normal X-ray. Investigation of choice for demonstrating basal skull fractures, which are poorly visualised by CT scanning. Pneumocephalus is easily evident on a plain skull X-ray.

non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, divided into four stages according to EEG activity:

non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, divided into four stages according to EEG activity:

– stage 2: sleep spindles occur (12–14 Hz) and high-amplitude K complexes.

pre-existing disease: e.g. patients with COPD show decreased total sleep time and REM sleep with frequent arousals caused by hypoxaemia, hypercapnia and coughing.

pre-existing disease: e.g. patients with COPD show decreased total sleep time and REM sleep with frequent arousals caused by hypoxaemia, hypercapnia and coughing.

drugs: e.g. benzodiazepines abolish stages 3 and 4 NREM sleep; opioid analgesic drugs increase arousal frequency; tricyclic antidepressant drugs, barbiturates and amfetamines inhibit REM sleep. Catecholamines increase wakefulness.

drugs: e.g. benzodiazepines abolish stages 3 and 4 NREM sleep; opioid analgesic drugs increase arousal frequency; tricyclic antidepressant drugs, barbiturates and amfetamines inhibit REM sleep. Catecholamines increase wakefulness.

anaesthesia and surgery: the stress response to surgery, fever, pain, opioids, starvation and age decrease stages 3 and 4 NREM sleep and abolish REM sleep on subsequent nights.

anaesthesia and surgery: the stress response to surgery, fever, pain, opioids, starvation and age decrease stages 3 and 4 NREM sleep and abolish REM sleep on subsequent nights.

Sleep deprivation may result in ICU delirium, increased catabolism (due to increased corticosteroid secretion and insulin resistance), fatigue and difficulty in weaning from ventilators.

Sleep apnoea/hypopnoea. Cessation (apnoea) or reduction of > 30% (hypopnoea) of breathing for > 10 s during sleep. Resultant hypoxaemia and hypercapnia causes arousal, thus disrupting normal sleep architecture. Affects 5–10% of the adult population. May have a central mechanism (caused by lack of respiratory drive, e.g. Ondine’s curse) or may be obstructive (obstructive sleep apnoea; OSA). OSA is caused by decreased tone of the pharyngeal muscles during deep sleep, resulting in intermittent upper airway obstruction.

obesity: neck circumference of > 40 cm (17 inches) is a good predictor of OSA.

obesity: neck circumference of > 40 cm (17 inches) is a good predictor of OSA.

pharyngeal abnormalities (e.g. retrognathia, tonsillar hypertrophy, acromegaly) and other conditions (e.g. hypothyroidism, neuromuscular disorders).

pharyngeal abnormalities (e.g. retrognathia, tonsillar hypertrophy, acromegaly) and other conditions (e.g. hypothyroidism, neuromuscular disorders).

sedative drugs (including alcohol) can precipitate or exacerbate the condition.

sedative drugs (including alcohol) can precipitate or exacerbate the condition.

loud snoring, restlessness, morning headaches and daytime somnolence.

loud snoring, restlessness, morning headaches and daytime somnolence.

medical consequences of OSA include increased incidence of cognitive disorders, hypertension, CVA, arrhythmias, MI and diabetes mellitus.

medical consequences of OSA include increased incidence of cognitive disorders, hypertension, CVA, arrhythmias, MI and diabetes mellitus.

severe OSA may result in cor pulmonale (obesity hypoventilation syndrome).

severe OSA may result in cor pulmonale (obesity hypoventilation syndrome).

Screening questionnaires are used to identify those at high risk; formal diagnosis requires sleep studies, with polysomnography (monitoring of respiratory airflow, chest and abdominal movements, EEG and oximetry). OSA severity is classified according to the apnoea–hypopnoea index (number of apnoeas/hypopnoeas divided by the number of hours of sleep): 5–15 = mild; 15–30 = moderate; > 30 = severe.

Treatment includes weight loss, nasal CPAP and removal of tonsils if enlarged. Uvulopharyngopalatoplasty (UVPP) is of dubious benefit. Tracheostomy may be indicated in severe cases.