CHAPTER 35 Rupture of the Triceps Tendon

INTRODUCTION

Rupture of the triceps tendon is rare.1,2,3 Anzel and colleagues2 reported that 85% of the 1015 tendon injuries treated at the Mayo Clinic involved the upper extremity. Of this group of 856, only 8 instances of triceps tendon injury were reported, and 4 of these were due to laceration. Since the first report of Partridge in 1868 as cited by Bennett,5 as of 2000, fewer than 50 instances have been recorded in the English literature.6,9,10,11 Unlike ruptures of the distal biceps tendon, this may occur both in men and women, with a female to male ratio of 2:3. The mean age of occurrence is about 33 years, but rupture has been observed in a broader spectrum of ages including children (aged 7) to adolescents in whom the olecranon physes has just closed,14 to individuals in the eighth decade.15

MECHANISM OF INJURY

Rupture of the triceps tendon may occur either spontaneously, after trauma, or after surgical release and reattachment. Two types of traumatic episodes may be implicated. The most common event is a deceleration force imparted to the arm during extension as the triceps muscle is contracting. This usually occurs during a fall, but avulsion has been reported due to simple, uncoordinated triceps muscle contraction against a flexing elbow.4,26 The association of triceps tendon avulsion39 or tear19 associated with body builders is consistent with the observation of muscle unit damage associated with eccentric contractures in the unconditioned muscle.24,31 The possibility of anabolic steroid usage must also be considered in this type of patient. A direct blow to the posterior aspect of the triceps at its insertion in varying positions also has been reported in several instances1,33,45 but is probably an uncommon mechanism of injury.

PREDISPOSING CONDITIONS

An association of olecranon bursitis has been noted to predispose to triceps tendon rupture.10 Disruption of the triceps also may occur spontaneously with minimal trauma in individuals who are compromised by a systemic disease process,35 such as renal osteodystrophy and secondary hyperparathyroidism.9,15 Although the pathophysiology of this association has not been completely explained, an increased amount of elastic fibers in the tendons of patients with renal osteodystrophy undergoing dialysis has been reported.29 Calcification due to the chronic hypercalcemia of secondary hyperparathyroidism may be yet another explanation for the associated tendon ruptures in this group of patients.35 Ruptures also have been reported in association with steroid treatment for lupus erythematosus45 and chronic acidosis,29 and in individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta tarda25 or Marfan’s syndrome.38 Diabetes has been recently implicated in a patient with triceps rupture at the musculotendinous junction.44

In spite of the association with debilitating states and conditions, this injury is well recognized in the athletic population as well. Such diverse activities as power weightlifting and handball have been implicated.13,19,24,39 It should be noted that the injury can be associated with localized hematoma, and there are reports of ulnar nerve compression as a result of hematoma compression after triceps rupture in power lifters.13,19 Triceps deficiency occurring after total elbow replacement is obviously a problem of exposure, and repair and is discussed elsewhere.7

DIAGNOSIS

Without question, a history of acute pain and weakness in extension or an eccentric loading in flexion against forcible triceps contracture, such as a fall on the outstretched hand, is the most reliable method of making this diagnosis. A palpable defect is present in some instances, depending on the extent of triceps retraction (Fig. 35-1). Injury to the muscular tendinous junction results in pain proximal to the olecranon.3,30 Some loss of extension power is universally observed. Some active elbow extension may be present, but extension against gravity is not possible with a complete rupture. The length/tension relationship of the triceps has been studied by Hughes and associates,20 who found that as little as 2 cm shortening between origin and insertion causes a marked (40%) loss of strength.

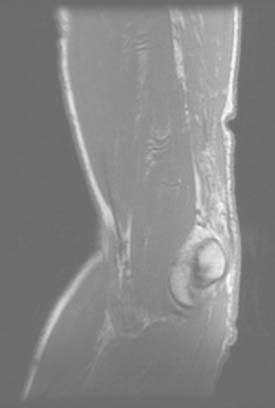

IMAGING

Today, imaging is a most reliable means of making a definitive diagnosis that more precisely defines the location and nature of the tear. A plain radiograph is extremely useful in that uncommon instance in which the triceps rupture occurs with a fleck of bone readilyidentified in the lateral film15,35,38 (Fig. 35-2). Without question, however, the advent of the magnetic resonant imaging has provided an accurate and reliable means of not only diagnosing this injury but also localizing the site and the extent of the pathology (Fig. 35-3).16,34 Ultrasonic diagnosis is also emerging as a reliable and less expensive imaging modality.31,34

PATHOLOGY

Theoretically, three sites of failure may occur and these have also been observed clinically: the muscle belly, the musculotendinous junction, and the osseous tendon insertion.27 For this particular injury, the failure has occurred almost universally at the site of insertion, although failure at the musculotendinous junction has occasionally been reported.18,28,44

Associated injuries also have been reported. Several instances of concurrent fracture of the radial head have been noted,35,42 and a recent report of six such injuries suggests that the association may be more common than is appreciated.23 I have not diagnosed this combination in my practice. A single report of fracture of the wrist22 along with fracture of the radial head supports the case for the mechanism of injury being a fall on the outstretched hand.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The diagnosis of a partial rupture may be difficult. Pain is not dysfunctional; thus, a number of patients present several weeks after the acute event.21 Furthermore, some weak residual extension power may be provided by the anconeus/triceps expansion. This effect can be negated by observing the inability to extend overhead against gravity. The radiograph is of considerable benefit for diagnosis of this injury in some patients, because flecks of avulsed bone are apparent on the lateral film (see Fig. 35-2).14,41

TREATMENT

PARTIAL RUPTURES

Incomplete tendon rupture should be initially treated nonoperatively.1 However, a distinction must be made between a true partial insertional rupture and one occurring at the musculotendinous junction. Improved imaging modalities are helpful to make this distinction.16,34 A true partial detachment from the olecranon does not reliably heal. With an acute injury, we do favor protecting the extremity and observing the amount of progress over a 6- to 8-week period. A strain of the attachment or of the musculotendinous junction will improve. Although appearing to heal, partial ruptures will continue to be symptomatic with increased activity. In the event that there is no clinical contraindication, surgical intervention is indicated. If there is evidence of healing by progressive resolution of symptoms, then in our judgment this represents a strain and not a rupture and nonoperative management is recommended.

COMPLETE RUPTURE

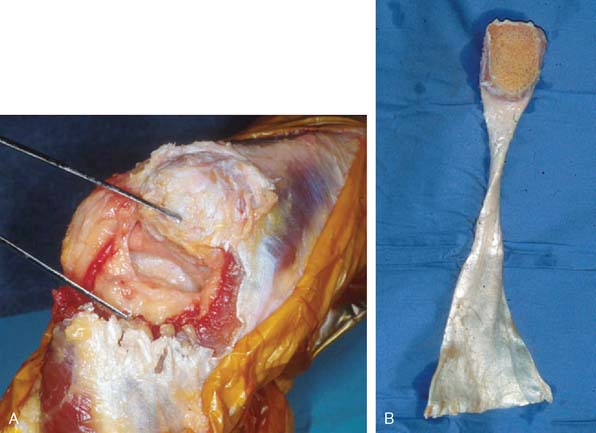

For complete rupture, immediate surgery is the treatment of choice. At the time of exploration, the tendinous portion of the triceps is usually involved and retracted within the muscle.22,35 However, complete disruption of the entire extension mechanism is uncommon. More than 90% of these injuries occur at the olecranon, with injury of the other sites being reported only occasionally.17,25 In our experience, the tendinous central third is most typically detached both with complete and partial injury.42 Lateral continuity with the anconeus is thus a common finding.

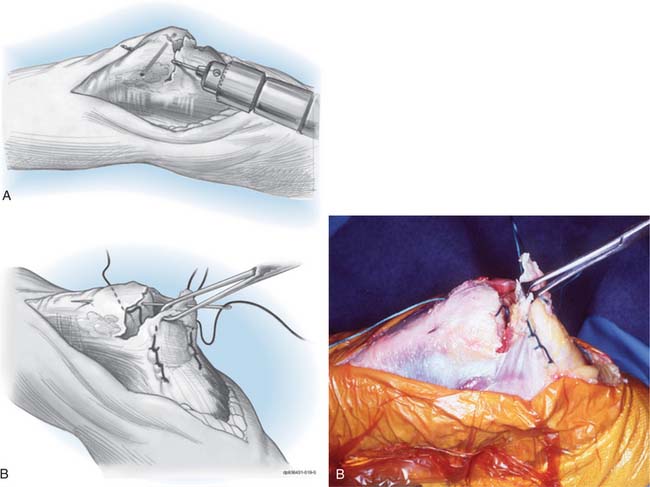

ACUTE

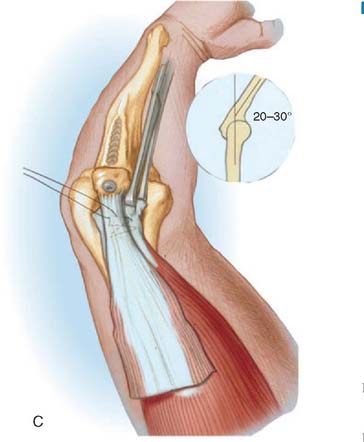

Direct attachment with a nonabsorbable suture through drill holes placed in the olecranon or through a subperiosteal flap is effective treatment for the acute injury. We employ a heavy No. 5 nonabsorbable suture and place two parallel rows of running locked stitches in the tendinous portion of the triceps mechanism (Fig. 35-4). The suture is then brought through cruciate drill holes in the olecranon. With the elbow extended to 30 degrees, the sutures are tied. To further ensure that the tendon is firmly approximated to its origin and to avoid poor healing from synovial fluid, a second transverse suture may be placed which more securely applies the tendon to its site of attachment. If there has been any delay in the treatment, the adventitial bursa tissue should be removed and the area scarified to ensure healing. Concurrent reconstructive options are not necessary in the acute (i.e., less than 2-week-old) injury.

DELAYED RECONSTRUCTION

Several reconstructive procedures have been reported for individual cases. Bennett5 and Farrar and Lippert14 describe a forearm fascial flap to reconstruct the triceps mechanism. The classic triceps fascial turndown procedure is not reliable, in our opinion,10 for those with soft tissue deficiency at the point of attachment.

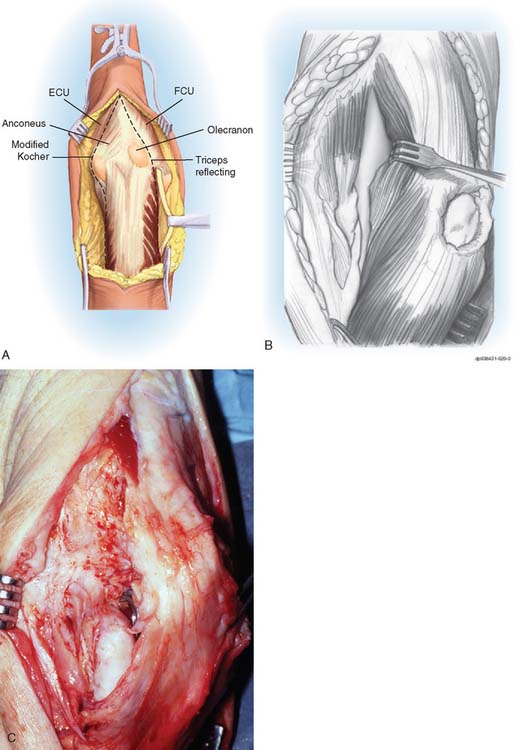

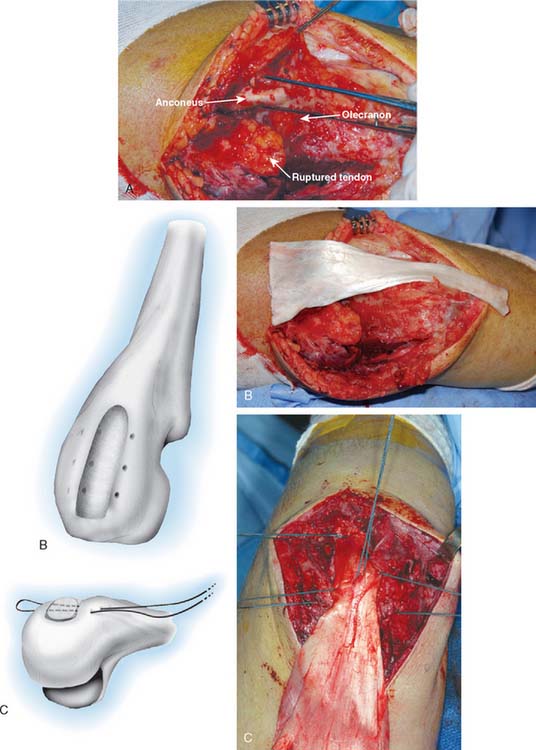

We use two reconstructive procedures: anconeus slide and achilles tendon allograft reconstruction.37 The slide is used for minor defects when the anconeus is intact.

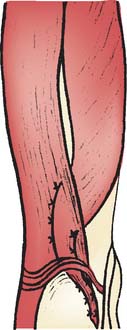

Technique

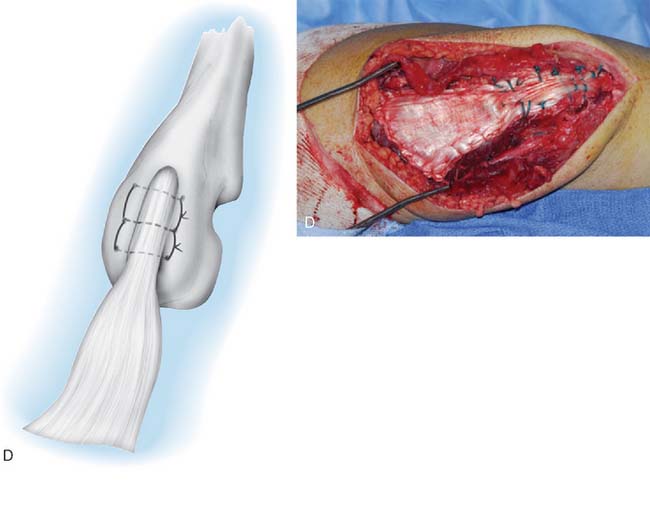

The patient is supine and the arm brought across the chest. Kocher’s interval between the anconeus and the extensor carpi ulnaris is entered. The anconeus is mobilized from its humeral and ulnar attachments in continuity with the triceps (Fig. 35-5). The triceps/anconeal sleeve is left attached distally and mobilized sufficiently medial to fully cover the site of triceps attachment (Fig. 35-6). The sleeve of extensor musculature is secured in a manner described earlier with a criss-cross No. 5 nonabsorbable suture. The suture is tied with the elbow at 30 degrees of extension. The tendinous fibers that are displaced medially are rotated under the tendon and sewn to themselves.

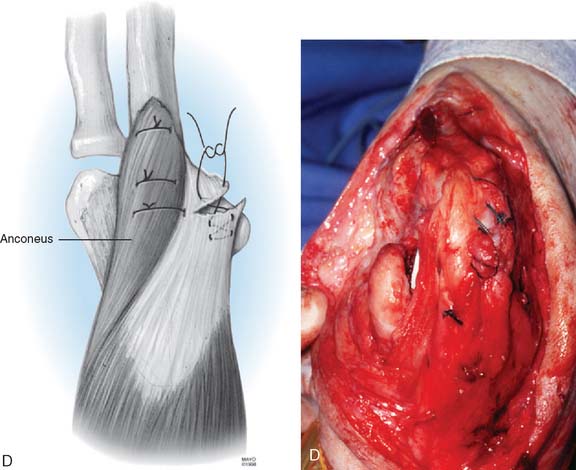

Achilles Tendon Allograft.

The allograft Achilles tendon has recently proven to be particularly attractive in those with marked deficiency (see Fig. 35-6).

In most instances, a trough is made in the subcutaneous border of the proximal ulna and the tendinous portion of the Achilles graft is inserted into the tendinous trough and secured with a No. 5 nonabsorbable suture placed through two drill holes in the proximal ulna (Fig. 35-7). The elbow is placed in 30 degrees of extension. The triceps musculature is mobilized as far distally as possible. The fascia is brought as far proximal as possible under tension and secured with a No. 5 suture. Once the No. 5 nonabsorbablesuture has been placed and secured, the elbow is brought into full extension relaxing the graft. The triceps tendon is brought distally, and the tendon is secured to the muscle and fascia of the triceps with running absorbable suture.

If osseous union is desired, a Chevron resection of the proximal olecranon is performed. A matching preparation of the calcaneal bone allows an osseous union of the distal site. The calcaneus is fashioned in a way to match the preparation of the proximal ulna (Fig. 35-8). The calcaneus is secured as an allograft to the olecranon with a cancellous screw, and the remainder of the repair is performed as described earlier.

In all reconstructive options, the construct is secured toward extension, such as about 40 to 60 degrees of flexion. After surgery, the arm is protected at 90 degrees of flexion for 3 weeks. Gentle active motion is begun. We have been impressed that recovery, even for acute repair, is slow, possibly taking 6 months to gain 80% of normal strength. Full function is often not realized for a year.

Results and The Mayo Experience

The results of immediate or delayed repair have ultimately been universally good. In most instances, marked improvement in strength and full motion have been restored. A loss of approximately 5 degrees of terminal extension strength has been regularly noted. Suprisingly, good results have been observed with repair or reconstruction that has been delayed for up to 1 year.45 However, as noted earlier, it should be emphasized that recovery may be slow and may take a year for full improvement.

Two comprehensive assessments of Mayo’s 20-year experience with 23 triceps deficiencies have been reported by van Riet et al.42 and 14 after total elbow by Celli et al.7 Of the 23 not related to joint replacement, there were 8 partial and 15 complete ruptures. Only 2 (8%) had osseous avulsions. Of these 23, 14 were primary repairs and 9 were reconstructions followed on average of 88 months. At final follow-up, the average arc of motion was 10 to 135 degrees. Isokinetic and dynamic testing in 10 patients showed peak strength of approximately 82% of the uninvolved extremity. The endurance, however, was almost 99% of normal. Of interest, results from repair and reconstruction were comparable but the recovery period was prolonged in those undergoing reconstruction. Overall, 90% were considered to have had a subjective satisfactory outcome and all patients were able to extend against gravity. In the group with deficiencies after total elbow, all but one was allowed to extend against gravity.

COMPLICATIONS AND RESIDUA

Few complications have been reported other than delayed recovery, variable loss of extension strength, and olecranon bursitis.32

AUTHOR’S PREFERRED TREATMENT METHOD

Immediate repair with a posterior incision just lateral to the midline is the treatment of choice. No. 5 nonabsorbable suture is placed in Bunnell fashion in the torn tendon and then through criss-crossed holes in the proximal ulna (see Fig. 35-4). If the avulsion has occurred with a sufficiently large fleck of bone, however, reattachment with the AO tension band technique is preferred.43 If the lesion has been overlooked or treatment delayed by several weeks or months, one of the two reconstructive procedures described earlier is carried out.

SNAPPING TRICEPS TENDON

The perception of a posterior snapping elbow is usually localized posteriorly and medially. The cause of such symptoms may be a subluxating ulnar nerve8 or dislocation of a portion of the triceps mechanism.41 Furthermore, an anomalous slip of the triceps tendon may cause these symptoms, but the most common etiology is subluxation of the medial head of the triceps over the medial epicondyle, usually occurring spontaneously in the second decade of life.12,36,40

A common associated finding with this condition is chronic irritation of the ulnar nerve, causing an ulnar neuritis.12,36 Other than this feature, however, the snapping is generally well tolerated. It is very important to recognize this relationship and be suspicious of a snapping triceps concurrent with a subluxating ulnar nerve.

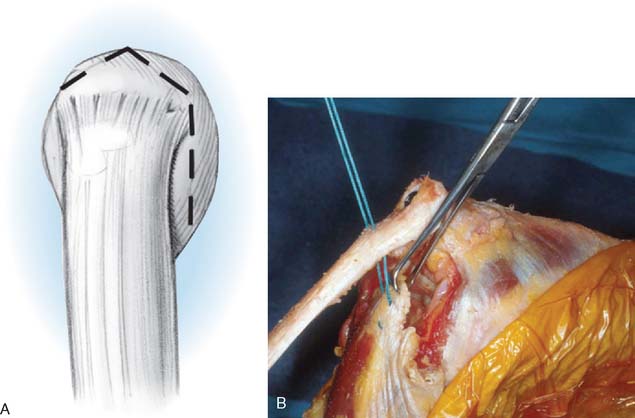

Treatment consists of simply detaching or releasing and rerouting the offending portion from the medial attachment under the triceps mechanism to its lateral attachment (Fig. 35-9). Management of the ulnar nerve is based on its degree of involvement, especially on the stability of the nerve.

1 Anderson K.J., LeCoco J.F. Rupture of the triceps tendon. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1957;39A:444.

2 Anzel S.H., Covey K.W., Weiner A.D., Lipscomb P.R. Disruption of muscles and tendons: An analysis of 1,014 cases. Surgery. 1959;45:406.

3 Aso K., Torisu T. Muscle belly tear of the triceps. Am. J. Sports Med. 1984;12:485.

4 Bauman G.I. Rupture of the biceps tendon. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1934;16:966.

5 Bennett B.S. Triceps tendon rupture. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1962;44A:741.

6 Brickner W.M., Milch H. Ruptures of muscles and tendons. Int. Clin. 1928;2:94.

7 Celli A., Arash A., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Triceps insufficiency following total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1964;87A:1957.

8 Childress H.M. Recurrent ulnar nerve dislocation at the elbow. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1975;1:168.

9 Cirincione R.J., Baker B.E. Tendon ruptures with secondary hyperparathyroidism. A case report. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1975;57A:852.

10 Clayton M.L., Thirupathi R.G. Rupture of the triceps tendon with olecranon bursitis: A case report with a new method of repair. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1984;184:183.

11 Debeyre J. Desinsertion du tendon inferieur du biceps brachial. Mem. Acad. Chir. 1948;74:339.

12 Dreyfuss U. Snapping elbow due to dislocation of the medial head of the triceps. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1978;60B:57.

13 Duchow J., Kelm J., Kohn D. Acute ulnar nerve compression syndrome in a powerlifter with triceps tendon rupture—a case report. Int. J. Sports Med. 2000;21:308.

14 Farrar E.L.III, Lippert F.G.III. Avulsion of the triceps tendon. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1981;161:242.

15 Fery A., Sommelet J., Schmitt D., Lipp B. Avulsion bilaterale simultanée des tendons quadricipital et rotulien et rupture du tendon tricipital chez un hemodialyse hyperparathyroidien. Rev. Chir. Orthop. 1978;64:175.

16 Fritz R.C., Steinbach L.S. Magnetic resonance imaging of the musculoskeletal system. Part 3. The elbow. Clin. Orthop. 1996;324:321.

17 Gerard F., Marion A., Garbuio P., Tropet Y. Distal traumatic avulsion of the triceps brachii. Apropos of a treated case. Chir. Main. 1998;17:321.

18 Gilcreest E.L. Rupture of muscles and tendons. J. A. M. A. 1925;84:1819.

19 Herrick R.T., Herrick S. Ruptured triceps in a powerlifter presenting as cubital tunnel syndrome: A case report. Am. J. Sports Med. 1987;15:514.

20 Hughes R.E., Schneeberger A.G., An K.-N., Morrey B.F., O’Driscoll S.W. Reduction of triceps muscle force after shortening of the distal humerus. A computational model. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6:444.

21 Inhofe P.D., Moneim M.S. Late presentation of triceps rupture: A case report and review of the literature. Am. J. Orthop. 1996;25:790.

22 Lee M.L.H. Rupture of triceps tendon. Br. Med. J. 1960;2:197.

23 Levy M., Fishel R.E., Stern G.M. Triceps tendon avulsion with or without fracture of the radial head: A rare injury? J. Trauma. 1978;18:677.

24 Louis D.S., Peck D. Triceps avulsion fracture in a weightlifter. Orthopedics. 1992;15:207.

25 Match R.M., Corrylos E.V. Bilateral avulsion fracture of the triceps tendon insertion from skiing with osteogenesis imperfecta tarda. Am. J. Sports Med. 1983;11:99.

26 Maydl K. Ueber subcutane Muskel und Sehnenzerreissungen, sowie Rissfracturen mit Berucksichtigung der Analogen, durch directe Gewalt enstandenen und offenen Verletzungen. Deut. Zschr. Chir.. 1882;17:306. 18:135, 1883.

27 McMaster P.E. Tendon and muscle ruptures: clinical and experimental studies on causes and locations of subcutaneous ruptures. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1933;15:705.

28 Montgomery A.H. Two cases of muscle injury. Surg. Clin. Chic. 1920;4:871.

29 Murphy K.J., McPhee I. Tears of major tendons in chronic acidosis with elastosis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1965;47A:1253.

30 O’Driscoll S.W. Intramuscular triceps rupture. Can. J. Surg. 1992;35:203.

31 O’Reilly K., Worhal M., Meredith C., et al. Immediate and delayed ultrastructural changes in skeletal muscle following eccentric exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1986;18(Suppl):S42.

32 Pantazopoulos T., Exarchou E., Stavrou Z., Hartofilakidis-Garofalidis G. Avulsion of the triceps tendon. J. Trauma. 1975;15:827.

33 Penhallow D.P. Report of a case of ruptured triceps due to direct violence. N.Y. Med. J. 1910;91:76-77.

34 Popovic N., Ferrara M.A., Daenen B., Georis P., Lemaire R. Imaging overuse injury of the elbow in professional team handball players: a bilateral comparison using plain films, stress radiography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging. Int. J. Sports Med. 2001;22:60.

35 Preston F.S., Adicoff A. Hyperparathyroidism with avulsion at three major tendons. N. Engl. J. Med. 1961;266:968.

36 Rolfsen L. Snapping triceps tendon with ulnar neuritis. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1970;41:74.

37 Sanchez-Sotelo J., Morrey B.F. Surgical techniques for reconstruction of chronic insufficiency of the triceps—rotation flap using anconeus and tendo Achilles allograft. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84B:1116.

38 Schutt, R. C., Powell, R. L., and Winter, W. G.: Spontaneous ruptures of large tendons. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Annual Meeting, New Orleans, January 25, 1982.

39 Sherman O.H., Snyder S.J., Fox J.M. Triceps tendon avulsion in a professional body builder: A case report. Am. J. Sports Med. 1984;12:328.

40 Spinner R.J., Goldner R.D. Snapping of the medial head of the triceps and recurrent dislocation of the ulnar nerve. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80A:239.

41 Tarsney F.F. Rupture and avulsion of the triceps. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1972;83:177.

42 van Riet R.P., Morrey B.F., Ho E., O’Driscoll S.W. Surgical treatment of distal triceps ruptures. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85A:1961.

43 Viegas S.F. Avulsion of the triceps tendon. Orthop. Rev. 1990;19:533.

44 Wagner J.R., Cooney W.P. Rupture of the triceps muscle at the musculotendinous junction: a case report. J. Hand Surg. 1997;22A:341.

45 Wener J.A., Schein A.J. Simultaneous bilateral rupture of the patella tendon and quadriceps expansions in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1974;56A:823.