Chapter 257 Rotaviruses, Caliciviruses, and Astroviruses

Etiology

Rotavirus, astrovirus, caliciviruses such as the Norwalk agent, and enteric adenovirus are the medically important pathogens of human viral gastroenteritis (Chapter 332).

Enteric adenoviruses are a common cause of viral gastroenteritis in infants and children. Although many adenovirus serotypes exist and are found in human stool, especially during and after typical upper respiratory tract infections (Chapter 254), only serotypes 40 and 41 cause gastroenteritis. These strains are very difficult to grow in tissue culture. The virus consists of an 80-nm-diameter icosahedral particle with a relatively complex double-stranded DNA genome.

Epidemiology

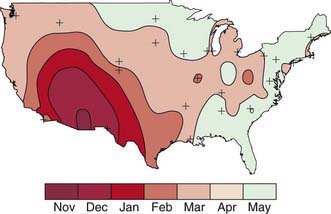

Rotavirus infection is most common in winter months in temperate climates. In the USA, the annual winter peak spreads from west to east (Fig. 257-1). Unlike the spread of other winter viruses, such as influenza, this wave of increased incidence is not due to a single prevalent strain or serotype. Typically, several serotypes predominate in a given community for 1 or 2 seasons, while nearby locations may harbor unrelated strains. Disease tends to be most severe in patients 3-24 mo of age, although 25% of the cases of severe disease occur in children >2 yr of age, with serologic evidence of infection developing in virtually all children by 4-5 yr of age. Infants younger than 3 mo are relatively protected by transplacental antibody and possibly breast-feeding. Infections in neonates and in adults in close contact with infected children are generally asymptomatic. Some rotavirus strains have stably colonized newborn nurseries for years, infecting virtually all newborns without causing any overt illness.

Treatment

Avoiding and treating dehydration are the main goals in treatment of viral enteritis. A secondary goal is maintenance of the nutritional status of the patient (Chapters 55 and 332).

Supportive Treatment

Rehydration via the oral route can be accomplished in most patients with mild to moderate dehydration (Chapters 55 and 332). Severe rehydration requires immediate intravenous therapy followed by oral rehydration. Modern oral rehydration solutions containing appropriate quantities of sodium and glucose promote optimum absorption of fluid from the intestine. There is no evidence that a particular carbohydrate source (rice) or addition of amino acids improves the efficacy of these solutions for children with viral enteritis. Other clear liquids, such as flat soda, fruit juice, and sports drinks, are inappropriate for rehydration of young children with significant stool loss. Rehydration via the oral (or nasogastric) route should be done over 6-8 hr, and feedings begun immediately thereafter. Providing the rehydration fluid at a slow, steady rate, typically 5 mL/min, reduces vomiting and improves the success of oral therapy. Rehydration solution should be continued as a supplement to make up for ongoing excessive stool loss. Initial intravenous fluids are required for the infant in shock or the occasional child with intractable vomiting.

Bresee JS, Parashar UD, Widdowson MA, et al. Update on rotavirus vaccines. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:947-952.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Addition of severe combined immunodeficiency as a contraindication for administration of rotavirus vaccine. MMWR. 2010;59(22):687-688.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Delayed onset and diminished magnitude of rotavirus activity-United States, Nov 2007–May 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:697-700.

Chandron A, Heinzen RR, Santosham M, et al. Nosocomial rotavirus infections: a systematic review. J Pediatr. 2006;149:441-447.

Clark B, McKendrick M. A review of viral gastroenteritis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2004;17:461-469.

Clark HF, Offit PA, Plotkin SA, et al. The new pentavalent rotavirus vaccine composed of bovine (strain WC3)–human rotavirus reassortants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:577-582.

Coffin SE, Elser J, Marchant C, et al. Impact of acute rotavirus gastroenteritis on pediatric outpatient practices in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:584-589.

Costa-Ribeiro H, Ribeiro TC, Mattos AP, et al. Limitations of probiotic therapy in acute, severe dehydrating diarrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;36:112-115.

Glass RI, Bresee JS, Parashar UD, et al. The future of rotavirus vaccines: a major setback leads to new opportunities. Lancet. 2004;363:1547-1550.

Grimwood K, Kirkwood CD. Human rotavirus vaccines: too early for the strain to tell. Lancet. 2008;371:1144-1145.

Guandalini S, Pensabene L, Zikri MA, et al. Lactobacillus GG administered in oral rehydration solution to children with acute diarrhea: a multicenter European trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30:54-60.

Guerrero ML, Noel JS, Mitchell DK, et al. A prospective study of astrovirus diarrhea of infancy in Mexico City. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:723-727.

Jiang B, Gentsch JR, Glass RI. The role of serum antibodies in the protection against rotavirus disease: an overview. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1051-1061.

Lynch M, Shieh WJ, Tatti K, et al. The pathology of rotavirus-associated deaths, using new molecular diagnostics. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1027-1033.

O’Ryan M, Diaz J, Mamani N, et al. Impact of rotavirus infections on outpatient clinic visits in Chile. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:41-45.

O’Ryan M, Matson DO. New rotavirus vaccines: renewed optimism. J Pediatr. 2006;149:448-451.

Parashar UD, Holman RC, Clarke MJ, et al. Hospitalizations associated with rotavirus diarrhea in the United States, 1993 through 1995: surveillance based on the new ICD-9-CM rotavirus-specific diagnostic code. J Infect Dis. 1998;77:13-17.

Parashar UD, Hummelman EG, Bresee JS, et al. Global illness and deaths caused by rotavirus disease in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:565-572.

Payne DC, Edwards KM, Bowen MD, et al. Sibling transmission of vaccine-derived rotavirus (RotaTeq) associated with rotavirus gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e438-e441.

Plotkin SA. New rotavirus vaccines. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:575-576.

Ruiz-Palacios GM, Perez-Schael I, Velazquez FR, et al. Safety and efficacy of an attenuated vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:11-22.

Soares-Weiser K, Goldberg E, Tamimi G, et al: Rotavirus vaccine for preventing diarrhoea, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD002848, 2004.

Staat MA, Azimi PH, Berke T, et al. Clinical presentations of rotavirus infection among hospitalized children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:221-227.

Tucker AW, Haddix AC, Bresee JS, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a rotavirus immunization program for the United States. JAMA. 1998;279:1371-1376.

Vesikari T, Matson DO, Dennehy P, et al. Safety and efficacy of a pentavalent human-bovine (WC3) reassortant rotavirus vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:23-33.