Rotator Cuff Repair and Rehabilitation

Lisa Maxey and Mark Ghilarducci

Etiology

Rotator cuff disorders are generally thought to have a multifactorial cause, including trauma, glenohumeral (GH) instability, scapulothoracic dysfunction, congenital abnormalities, and degenerative changes of the rotator cuff. Intrinsic factors of primary tendon degeneration and extrinsic mechanical factors have been described extensively and are felt to be the primary contributors of rotator cuff pathology. Intrinsic tendon degeneration has been described. In 1931, Codman and Akerson1 suggested that degenerative changes in the rotator cuff lead to tears. Microvascular studies of the vascular pattern of the rotator cuff have demonstrated a hypovascular zone in the supraspinatus adjacent to the supraspinatus insertion into the humerus.2–4 Relative ischemia in this hypovascular zone is believed to lead with aging to decreased tendon cellularity and the eventual disruption of the rotator cuff attachment to bone.

Compression of the rotator cuff between the acromion and the humeral head may subject the cuff to wear as the supraspinatus passes under the coracoacromial arch. Neer5,6 postulated that 95% of rotator cuff tears are caused by impingement of the rotator cuff under the acromion. Neer5 classified three stages of impingement as a continuum that eventually led to cuff tears. Stage I is characterized by subacromial edema and hemorrhage of the rotator cuff and usually occurs in patients younger than 25 years old. Stage II includes fibrosis and tendinosis of the rotator cuff and occurs more commonly in patients 25 to 40 years old. Stage III is a continued progression characterized by partial or complete tendon tears and bone changes. Typically, this involves patients older than 40 years old.5 Bigliani, Morrison, and April7 described three types of acromion shapes: (1) type I is flat, (2) type II is curved, and (3) type III is hooked. An increased incidence of rotator cuff tears is associated with a curved (type II) or a hooked (type III) acromion. Other sources of extrinsic impingement postulated include acromioclavicular (AC) osteophytes, the coracoid process, and the posterosuperior aspect of the glenoid.8

A rotator cuff tear may occur spontaneously after a sudden movement or a traumatic event.9 Ruptures of the rotator cuff have been estimated to occur in up to 80% of persons older than 60 years of age with GH dislocations.10 Cuff tears usually occur late in the shoulder deterioration process (after secondary impingement) and in older adults.

In athletes who participate in repetitive overhead activities (e.g., throwers, swimmers, tennis players), small rotator cuff tears may appear late in the deterioration process from secondary impingement. Secondary impingement is caused by instability of the GH joint or by functional scapulothoracic instability.11 The primary underlying GH instability may progress along a continuum from anterior subluxation to impingement to rotator cuff tearing. Treatment must be directed to the primary instability problem.12

The throwing athlete also may have secondary impingement caused by functional scapular instability. Fatigue of the scapular stabilizers from repetitive throwing leads to abnormal positioning of the scapula. As a result, humeral and scapular elevation lose synchronization and the acromion is not elevated enough to allow free rotator cuff movement.11 The rotator cuff abuts the acromion, causing microtrauma and impingement. A tear may gradually or spontaneously occur.

In summary, rotator cuff disease has a multifactorial cause. Vascular factors, impingement, degenerative processes, and developmental factors all contribute to the overall evolution and progression of rotator cuff disorders (Box 5-1).

Clinical Evaluation

History

The majority of patients with rotator cuff dysfunction have pain. They may complain of fatigue, functional catching, stiffness, weakness, and symptoms of instability. An acute or macrotraumatic presentation is important to distinguish from an overuse or microtrauma presentation. Most patients report a gradual onset of pain with no history of trauma. A gradual onset of weakness is usually associated with a chronic tear and an acute onset of weakness after years of shoulder pain is suggestive of an acute on chronic tear.

Pain is typically localized in the upper arm in the region of the deltoid tuberosity and anterior lateral acromion. Pain is usually worse at night. Overhead activities often induce the patient’s symptoms. Typical findings are a loss of endurance during activities, catching, crepitus, weakness, and stiffness.

Physical Examination

A thorough examination of the shoulder should include evaluation of the cervical spine and an upper extremity neurologic examination. The opposite shoulder must also be examined for comparison. Inspection, palpation for tenderness, and range of motion (ROM) tests should be completed. Palpation should include the AC joint, sternoclavicular (SC) joint, subacromial space, biceps tendon, trapezius muscle, and cervical spine. Impingement sign tests as described by Hawkins, Misamore, and Hobeika13 (i.e., forward flexion to 90° and internal rotation) and by Neer and Welch14 (forward elevation and internal rotation) are performed to elicit pain. If these tests produce pain, then they are considered positive signs of impingement and suggest rotator cuff dysfunction. The rotator cuff muscles are tested for strength. Subscapularis muscle strength tests include the lift-off test and the belly-press test. The lift-off test places the arm behind the back and up the spine. The patient is then asked to lift the hand off the back against restriction. The belly-press test places the arms onto the elbows bent to 90°, and the elbows are then lifted anteriorly against resistance. Examination for instability is performed. Apprehension sign, a positive-relocation test, or inferior sulcus sign are all indicative of instability. Stability testing should be performed in different positions (i.e., seated, supine) to eliminate instability as the cause of secondary impingement. Evidence of rotator cuff pathology includes painful impingement signs or weakness and a painful arc of motion.5

Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic testing includes injections, radiographs, arthrogram, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasonography. An impingement test (subacromial space injection with at least 10 mL of 1% lidocaine) is invaluable in evaluating the origin of shoulder pain. Physical examination several minutes after the injection, including for ROM, impingement signs, strength, and instability should be completed. Resolution of the shoulder symptoms without instability indicates primary rotator cuff pathology or impingement. Relief of pain with evidence of instability indicates possible primary instability with secondary rotator cuff changes because of altered shoulder mechanics.

Convention radiography is an important tool in the evaluation of rotator cuff tear pathology and is used to rule out arthritis and fractures, assess the morphology of the acromion, and look for calcifications about the shoulder. Arthrography is no longer the gold standard for identification of rotator cuff tears. Although reliable for the diagnosis of complete rotator cuff tears, it is less reliable for the evaluation of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. MRI has evolved to provide an excellent noninvasive tool in the diagnosis of rotator cuff pathology and the shoulder labrum and is the modality of choice for the evaluation of cuff tear pathology, followed by ultrasonography. MRI provides information not available by other diagnostic testing, including muscle atrophy, amount of rotator cuff retraction in full-thickness tears, bursal swelling, the status of the AC joint, and the shoulder articular cartilage. The combination of intraarticular contrast (gadolinium) and MRI (magnetic resonance arthrography) has been developed to better delineate abnormalities of the rotator cuff and labrum including partial surface rotator cuff tears.15,16 Ultrasonography of the shoulder has increased in popularity, and as technical advances continue to improve, it has become an increasingly useful tool in the diagnosis of cuff pathology. Ultrasonography has several advantages. These include a relatively low cost, the lack of the contraindications as with MRI, and its use in the examination of the patient both statically and dynamically. Unfortunately, the accuracy of ultrasonography is operator dependent and typically requires a long learning curve.

Treatment

Symptoms of rotator cuff dysfunction are usually treated initially in a nonoperative fashion (tendonitis, partial- or full-thickness rotator cuff tears). Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), heat, ice, relative rest, cortisone injection, and rehabilitation programs are used in the treatment. The initial goal of treatment is restoration of normal ROM. This is followed by a rotator cuff strengthening program. Stretch cords for resistance are initiated and are followed by free weights as tolerated. To avoid aggravation of the rotator cuff, all strength training initially should be below shoulder level. External rotation strengthening with the arm at the side may minimize subacromial pressure and pain while increasing the cuff’s ability to act as a humeral head depressor.

Nonoperative treatment programs usually continue for 3 to 6 months. Success varies from 50% to 90%.17–21 Approximately 50% of patients with complete symptomatic rotator cuff tears have satisfactory results with nonoperative measures, but these results may deteriorate with time.22 This wide range of outcomes is likely the result of lack of uniformity in classification, indications, and treatment. Some individuals have rotator cuff tears with no pain and normal function, whereas others may have debilitating pain. This demonstrates a need for better understanding of the factors that lead to symptoms.

Indications for Surgery

Indications for rotator cuff surgery include failure of 3 to 6 months of conservative care or an acute full-thickness tear in an active patient younger than 50 years. Failure of treatment can be determined before an entire rehabilitation course is completed. Indications for earlier surgical treatment can include return to full strength with persistent symptoms, failure to tolerate therapy because of pain, or plateau of initial improvement with persistent symptoms. Early surgical intervention is also indicated for patients sustaining acute trauma with full-thickness tears associated with significant rotator cuff weakness and posterior cuff involvement, particularly in young patients with higher functional demands. In addition, patients with acute tears or extension of chronic cuff tears may benefit from early surgery.23

In general, the duration of nonoperative treatment must be individualized based on pathology involved, the patient’s response to treatment, and individual functional demands and expectations.

Surgical Goals

The primary goal of rotator cuff surgery is decreased pain, including rest pain, night pain, and pain with activities of daily living (ADLs). Arrest of the progression of rotator cuff pathology and improved shoulder function are additional surgical goals.

Surgical Procedures

Tendonitis and Partial Rotator Cuff Tear

Surgical management for impingement syndrome generally involves open anterior acromioplasty as described by Neer63 or arthroscopic subacromial decompression (SAD) with release or partial release of the coracoacromial ligament. The coracoacromial ligament is released from the undersurface of the anterior and lateral acromion. An acromioplasty is performed using a burr to achieve a flat acromion. If osteophytes are present on the inferior surface of the AC joint, they are removed from the distal clavicle. Partial thickness cuff tears may be bursal or articular sided. Partial thickness cuff tears may be treated with débridement alone, débridement and acromioplasty, or rotator cuff repair. A subacromial decompression/acromioplasty is generally indicated if the partial tear is bursal sided or there are signs of mechanical impingement. Partial rotator cuff tears greater than 50% of the width of the tendon generally are treated with arthroscopic repair insitu or transtendineus repair, or may be treated with takedown and repair of the rotator cuff either miniopen or arthroscopic.24 Repair of partial-thickness tears improves results compared with débridement alone in this patient group. The overhead throwing athletes with rotator cuff disease have different requirements. Acromioplasty is rarely necessary in the throwing athlete.

Results of surgical treatment of low-grade (<50%) partial-thickness rotator cuff tears after débridement with and without acromioplasty have reported 75% to 88% satisfactory outcome on short-term follow-up.18,25–27 Repair of a high-grade (>50%) partial-thickness tear has had similar outcome to débridement of a low-grade partial-thickness tear or repair of a small full-thickness cuff tear.28

Full-Thickness Tears

The mainstay of treatment for full-thickness tears is surgical repair. The type, pattern, and size of the tear, as well as the surgeon’s preference, dictate whether the repair is a full-arthroscopic, miniopen, or a completely open procedure.

Small- or moderate-sized (3 cm or less) partial- or full-thickness supraspinatus or infraspinatus tears may be repaired fully with an arthroscopic or miniopen technique. Large width (3 to 5 cm) tears may also be repaired miniopen or arthroscopic if the cuff is mobile enough to allow anatomic repair.

Large, immobile cuff tears involving the subscapularis or teres minor, as well as tears of the musculotendinosis junction, may require an open approach. Massive chronic atrophic cuff tears should be considered for arthroscopic débridement for pain control.

Surgical Technique

All operative procedures discussed in recent literature for primary repair of rotator cuff tears include use of an anterioinferior acromioplasty to decompress the subacromial space. The author presently performs GH arthroscopy and subacromial bursoscopy on all patients undergoing surgery for cuff pathology.

Shoulder arthroscopy and decompression is performed as previously described. After acromioplasty, the bursal surface of the rotator cuff is evaluated. With shoulder rotation, the cuff can be completely visualized. Mobile tears may be treated with a miniopen technique or with arthroscopic repair.

Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair

In the past decade as arthroscopic repair of rotator cuff tears has become more widespread, there have been significant advances in arthroscopic surgical techniques and instrumentation. Arthroscopic repair involves the same general steps as miniopen or open rotator cuff repair. Bony landmarks are outlined and marked with a sterile pen. Multiple arthroscopic portals are made. Posterior, anterior, and lateral portals are made for all arthroscopic repairs. Additional portals are made depending on the rotator cuff tear configuration and include posterior lateral, anterior lateral, and lateral acromial portals. These allow access to various rotator cuff configurations and for suture anchor placement. The GH joint is completely and systematically evaluated followed by subacromial bursoscopy. The subacromial bursa is excised, and the anterior acromion is flattened with a burr. If symptomatic, then the AC joint is excised arthroscopically. The rotator cuff is visualized. The quality and the integrity of the rotator cuff are evaluated. The mobility of the cuff is evaluated. Adhesions on the bursal and articular sides of the tear are released. The goal is a mobile cuff which can be repaired to the normal footprint on the greater tuberosity with minimal tension. A three dimensional understanding of the cuff tear configuration is developed. Margin convergence repair principles are used for U-shaped tears or L- or reverse L-shaped tears. Sutures are placed in a side-to-side fashion through the anterior and posterior leafs of the tear. This convergences the edges of the tear and minimizes the tension on the tendon to bone repair. The result may be an arthroscopic repair of an otherwise irreparable tear. The greater tuberosity of the humerus is lightly decorticated with a burr. The tendon is then repaired to bone with suture anchors. The number of suture anchors used is predicated on the size of the tear and its configuration. In general, one suture anchor is used for each one centimeter of cuff tear.

Miniopen Rotator Cuff Repair

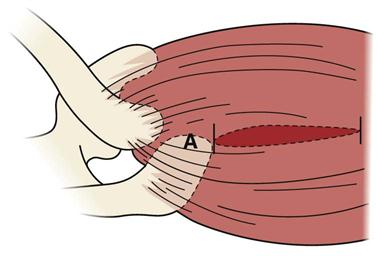

In the miniopen procedure, the lateral subacromial portal incision is extended either longitudinally or transversely to expose the deltoid fascia. The deltoid fascia is then split in line with its fibers directly over the tear. The anterior deltoid insertion of the anterior acromion is preserved. The deltoid fibers should not be split more than 4 cm lateral to the lateral acromion to avoid axillary nerve injury (Fig. 5-1). Rotation of the arm provides access to the tear. Digital palpation can be used to assess the adequacy of the acromioplasty. A bony trough is prepared in the greater tuberosity of the humerus. The rotator cuff may then be repaired through a bony bridge or with suture anchors. The permanent sutures are tied, pulling the rotator cuff down into its trough on the humerus.

Open Rotator Cuff Repair

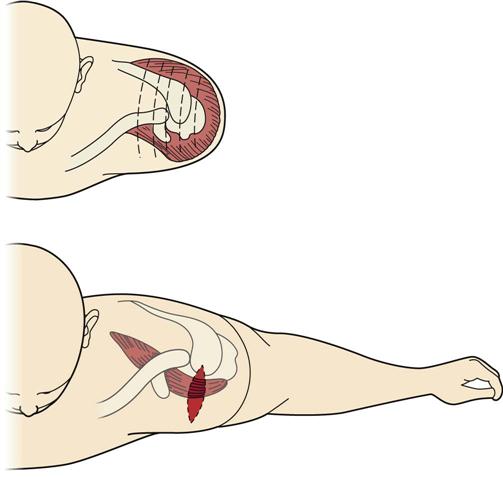

Tears that are fixed, retracted, but reparable, may be repaired open using principles developed by Neer.5,6 An oblique incision in Lagers line from the anterior edge of the acromion to a point about 2 cm lateral to the coracoid process is made. The anterior deltoid is released from the anterior aspect of the acromion and splitting the deltoid no more than 4 cm lateral to the acromion (Fig. 5-2). The deltoid origin over the acromion is elevated subperiosteally. The coracoacromial ligament is released.

The anterior acromion is osteotomized. The acromion anterior to the anterior aspect of the clavicle is removed, and the undersurface of the acromion is flattened from anterior to posterior. The AC joint may be removed if arthritic and symptomatic. The distal clavicle is excised parallel to the AC joint so that no contact occurs with adduction of the arm.

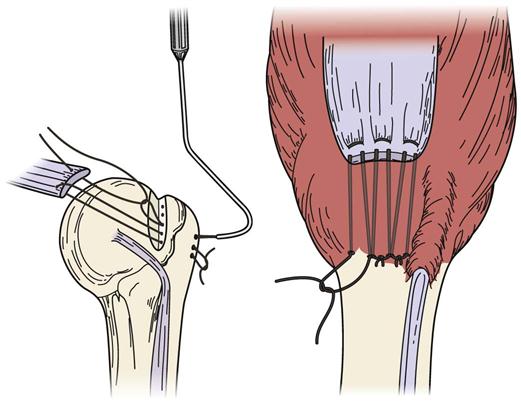

The cuff tear is visualized and mobilized. A bony trough 0.5 cm in width parallel to the junction of the humeral articular cartilage and greater tuberosity of the humerus is made. The rotator cuff tear is repaired to bone with suture anchors or through a bony bridge in the greater tuberosity using permanent sutures (Fig. 5-3). The goal is to repair the cuff with minimal tension with the arm at the side.

Watertight repairs are not necessary for good functional outcome. Excellent and good results have been shown in patients with residual cuff holes.29,30 The anterior deltoid is repaired back to the acromion by preserved periosteum or through drill holes with permanent sutures. Routine skin closure is performed.

Postoperative management of cuff repairs must be individualized to incorporate tear size, tissue quality, difficulty of repair, and patient goals. Passive motion is initiated immediately. In general, supine active-assisted motion is started on the first postoperative day. Waist-level use of the hand can usually be started after surgery. Active ROM and isotonic strengthening are started 6 to 8 weeks after surgery. Progress of strengthening is individualized with full rehabilitation taking from 6 to 12 months. Function can continue to improve for 1 year after surgery.

Management of Massive Tendon Defects

The management of massive irreparable tendon defects remains controversial. Options include SAD and débridement of nonviable cuff tissue without attempt at repair, use of autogenous or allograft tendon grafts, and use of active tendon transfers. Operations that require tendon transfer to nonanatomic sites to cover rotator cuff defects are likely to alter mechanics of the shoulder unfavorably.31 Débridement may be pursued (either open or arthroscopic).

Results of Treatment of Full-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tears

Satisfactory results after rotator cuff repair for pain relief occur 85% to 95% of the time5,13,32,33 and appear to correlate with the adequacy of the acromioplasty and SAD. Functional outcomes correlate with integrity of the cuff repair, preoperative size of the cuff tear, and quality of the tendon issue. Poor outcomes are also associated with deltoid detachment or denervation.34

Arthroscopic-assisted miniopen rotator cuff repair provides favorable clinical results. Results comparable with open cuff repair have been reported for small- and moderate-sized rotator cuff repair (less than 3 cm.).35–37 These studies have shown the most important factor affecting outcome was cuff tear size. Tears of small or moderate size had better results. Blevins and associates,38 in a retrospective study, have shown 83% good or excellent results regardless of cuff size. Most studies have shown more rapid return to full activities with miniopen repair.

Fully arthroscopic repair studies have shown outcomes approaching the results of open rotator cuff repair or miniopen rotator cuff repair.39–47

A surgical technique that initially includes arthroscopy has the advantage of providing identification and treatment of intraarticular pathology (articular cartilage, labrum, biceps tendon). Additional advantages of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair include decreased soft tissue dissection, improved cosmesis, preservation of the deltoid attachment, decreased postoperative pain, and earlier return of normal ROM.

Unfortunately, rehabilitation cannot be accelerated for arthroscopic or miniopen cuff repairs because the limiting factor, tendon-to-bone healing, is not changed by the surgical technique.

No ideal surgical technique exists. Each surgeon must individualize treatment based on the type of lesion present, as well as the expertise of the physician. As has been noted over the past decade with the widespread use of shoulder arthroscopy and improved surgical technique and instrumentation, arthroscopic rotator cuff surgery will continue to increase in frequency and open or miniopen cuff repairs will continue to decrease in frequency. All these methods have a role in the treatment of rotator cuff tears.

Therapy Guidelines for Rehabilitation

The general guidelines that follow are for the rehabilitation of a type 2 rotator cuff tear (a medium-to-large rotator cuff tear that is larger than 1 cm and smaller than 5 cm). We have also included a table of guidelines to follow for large tears. The protocol is designed for active patients (i.e., recreational athletes, laborers). Older, more sedentary individuals progress through the stages more slowly. These patients are not appropriate candidates for the more aggressive exercises. Recent studies suggest that longer periods of immobilization and a more conservative approach to restoring ROM early on leads to more successful outcomes in terms of fewer repeat tears following surgery or insufficient healing of the rotator cuff. Even if the tear is not completely healed, the patient can be satisfied with the results. However, they are happier if the cuff is healed. Therefore, the goal is for a healed rotator cuff repair. Too many ROM exercises or too much stress on the repaired tissues early on may create an increase in scar tissue. This tissue has a poorer quality of intracellular tissue. Studies have also shown that after 1 year there is no difference in the ROM of patients in different groups following surgery.48 Groups that received early ROM treatment versus groups that received delayed ROM treatments had the same ROM at 1 year. The group that delayed ROM treatments actually had a higher rate of healing versus the group who received passive range of motion (PROM) early in the rehabilitation process.48

Many factors contribute to the healing rates of these repairs: retraction of the tissue, age, early repair versus late repair, surgical technique, patient selection, and postoperative rehabilitation. Poorer outcomes have been noted with patients over 65 years of age, manual laborers, those with poor bone stock, tears greater than 5 cm, workers’ compensation cases, or active litigation clients. Better outcomes have been noted with younger patients, smaller tears, and early surgical repair. In light of the recent discussion of early versus delayed ROM following a rotator cuff repair, we are presenting a more conservative approach to rehabilitating these patients in this third edition. Patients who have early signs of stiffness should be treated with a more liberal approach to restoring ROM. Benefits to early ROM treatments are minimal; however, the benefits to maintaining a safe environment for optimal healing are far more beneficial. The goal is to avoid overstressing the healing tissues and preventing shoulder stiffness.

These guidelines are designed to help guide therapists and provide treatment ideas. The scope of this chapter does not include instructions on treatment methods or applications. All modalities, mobilizations, and exercises suggested in this chapter are recommended only for therapists who have been trained in these methods and can appropriately apply them. The therapist must choose the treatments that are beneficial and safe for each patient while following the restrictions outlined by the operating surgeon.

Phase I

TIME: 1 to 4 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Comfort, maintain integrity of repair, increasing ROM as tolerated without progressing to full range, decreased pain and inflammation, minimal cervical spine stiffness, protection of the surgical site, maintenance of full elbow and wrist ROM (Table 5-1)

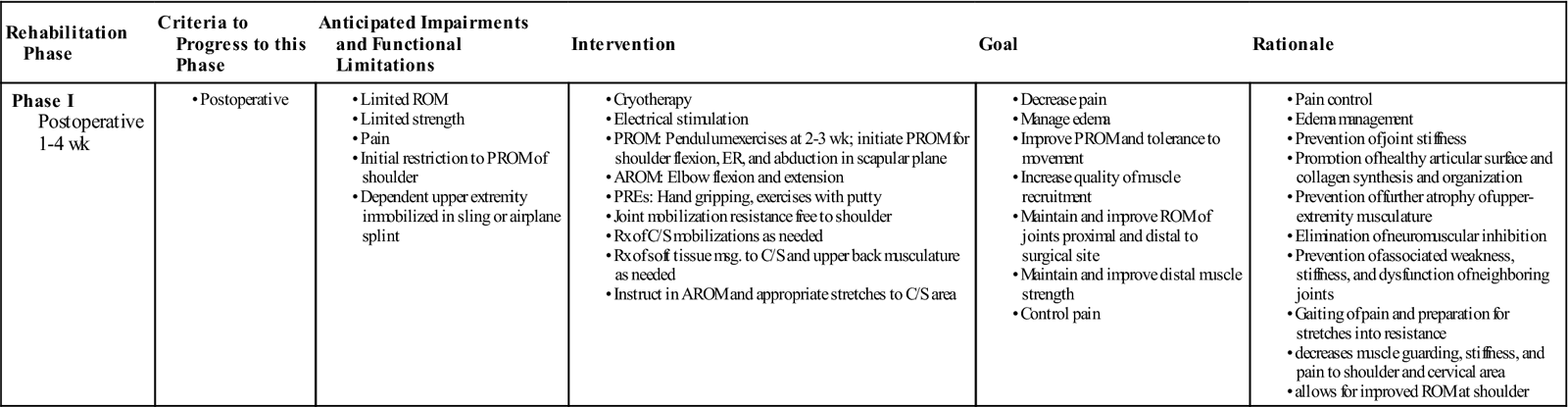

TABLE 5-1

Rotator Cuff Repair for Moderate-Sized Tears

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to this Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

|

Phase I Postoperative 1-4 wk

|

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Refer to Box 5-2 for a shoulder evaluation following a rotator cuff repair. The therapist must maintain the protection of the patient and the surgical repair while obtaining an evaluation; therefore, some tests will need to be deferred until later in the treatment process.

To reduce pain and swelling, use cryotherapy. Electrical stimulation may also be used for pain reduction. Instruct the patient in posturing for comfort. Encourage the patient to experiment with different positions. Usually a loose packed GH position (shoulder in some flexion, abduction, and internal rotation) with the arm supported by pillows while supine or sitting is more comfortable. Usually patients cannot sleep much after surgery in the supine position. Therefore suggest sleeping semireclined in a recliner chair with the upper extremity supported in the loose packed position. The patient may also try the supine position in bed, with the arm supported by pillows in a loose packed position.

Gentle mobilizations using grades I and II oscillations, and distractions may help reduce pain, muscle guarding, and spasms. These mobilizations also help maintain nutrient exchange and therefore prevent the painful and degenerating effects that long periods of immobilization produce (i.e., a swollen and painful joint).18 Occasionally, some people produce increased levels of scar tissue and tighten up quickly. For these cases, passive exercises provide nourishment to the articular cartilage and assist in collagen tissue synthesis and organization.49–51 The organization of collagen may then follow stress patterns, and adverse collagen tissue formation may be minimized. Limited periods of PROM and pendulum exercises are initiated during this initial stage. For large to massive tears, consider withholding PROM exercises until 4 weeks postsurgery. Recently, it has been suggested that early ROM or excessive ROM treatment of the GH joint may delay tissues from healing. Therefore, when conducting PROM treatments, be careful to protect healing tissues from too much stress from ROM exercises. PROM exercises are done in protected planes. PROM exercises for shoulder flexion are initiated in the scapular plane with the elbow flexed 90°, and external rotation is done with the palm facing the patient and beginning at 45° of abduction.52 Performing PROM exercises in the scapular plane is beneficial because of decreased tension on the capsuloligament-tendon complex.52 “Rotation exercises should be initiated at 45° of abduction to minimize tension across the repair.”52

![]() Remember to avoid horizontal adduction, extension, and internal rotation during this phase. Also advise patients to avoid leaning on the elbow, sleeping on the affected side, sudden movements, pushing/pulling, lifting, and carrying for 12 weeks.53

Remember to avoid horizontal adduction, extension, and internal rotation during this phase. Also advise patients to avoid leaning on the elbow, sleeping on the affected side, sudden movements, pushing/pulling, lifting, and carrying for 12 weeks.53

A general guideline to use in judging the force being applied is slight discomfort with a slight increase in motion after several repetitions. Remain sensitive and aware of the feedback the patient’s body is exhibiting during ROM or mobilization techniques. The patient’s response will dictate the amount of force applied or the plane of movement chosen. If muscle guarding continues to increase after several repetitions, the force being applied should be reduced or the plane of movement chosen needs to be slightly altered or decreased (or both need to be done) to avoid pinching sensations or increased pain. The therapist usually can find a groove (i.e., line of movement that can be progressed more easily) or line of motion with less muscle guarding. Therefore, constantly assess treatment application while treating the patient with manual PROM. Vary the treatment application as the patient’s feedback dictates (i.e., exact plane of movement, force, and repetitions). An increase in ROM will often accompany a decrease in pain if executed with a sensitive hand. However, general treatment soreness may be expected. Treatment soreness is usually more pronounced when progressing the patient from PROM to active range of motion (AROM) and then again when progressing to resisted ROM exercises. Remember during this stage we do not want full ROM. The superseding goal is to provide an environment where the tissues can heal while preventing stiffness.

Patients usually exhibit protective muscle guarding from the necessary insult of the surgery and the preceding shoulder pathology. Muscle guarding is present in the cervical region and the shoulder musculature. Therefore patients perform cervical AROM exercises and stretches. Appropriate cervical spine mobilization techniques may be valuable for decreasing cervical joint stiffness and muscle guarding, allowing more unrestricted movement of the shoulder complex.

Phase II

TIME: 5 to 8 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Protection of surgical site, improvement of ROM, increase in active strength, decrease in pain and inflammation, maintenance of elbow and wrist ROM, and minimizing of cervical stiffness (Table 5-2)

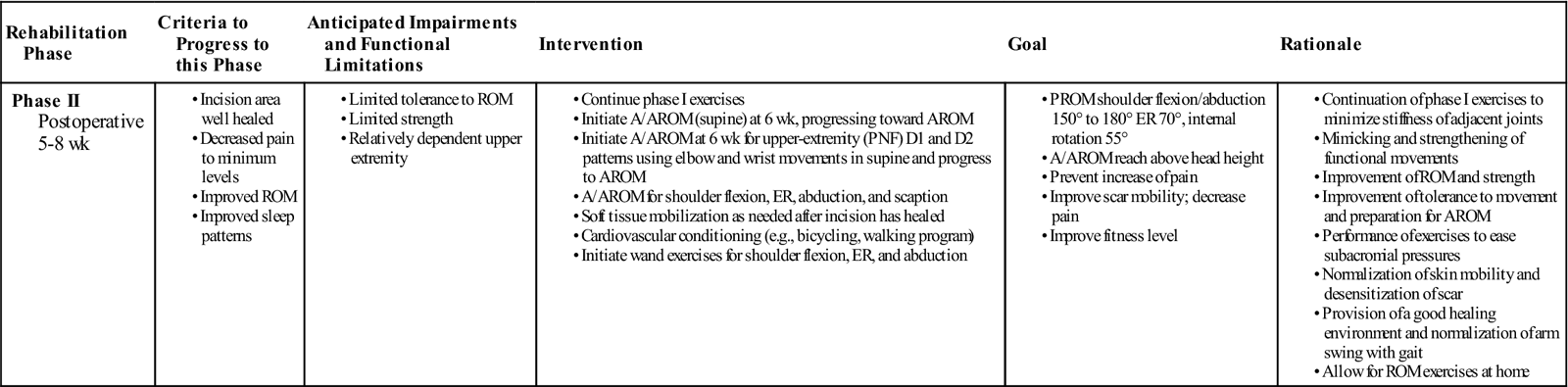

TABLE 5-2

Rotator Cuff Repair for Moderate-Sized Tears

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to this Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

|

Phase II Postoperative 5-8 wk

|

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

![]() During the second phase, the therapist should avoid overstretching muscles into positions that could compromise the repaired tissues (e.g., horizontal adduction, internal rotation beyond 70°, shoulder extension).

During the second phase, the therapist should avoid overstretching muscles into positions that could compromise the repaired tissues (e.g., horizontal adduction, internal rotation beyond 70°, shoulder extension).

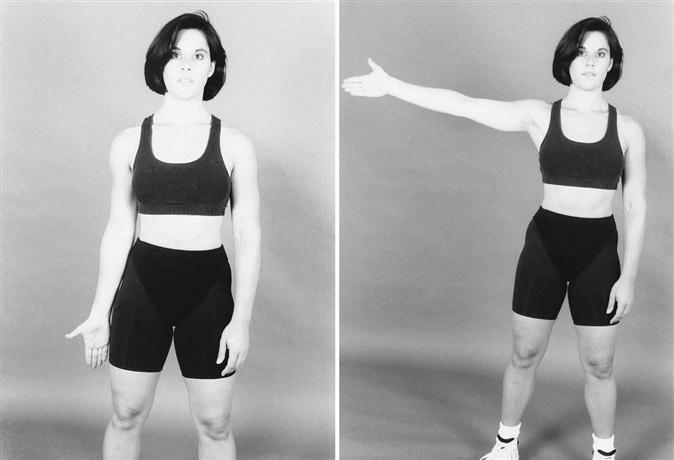

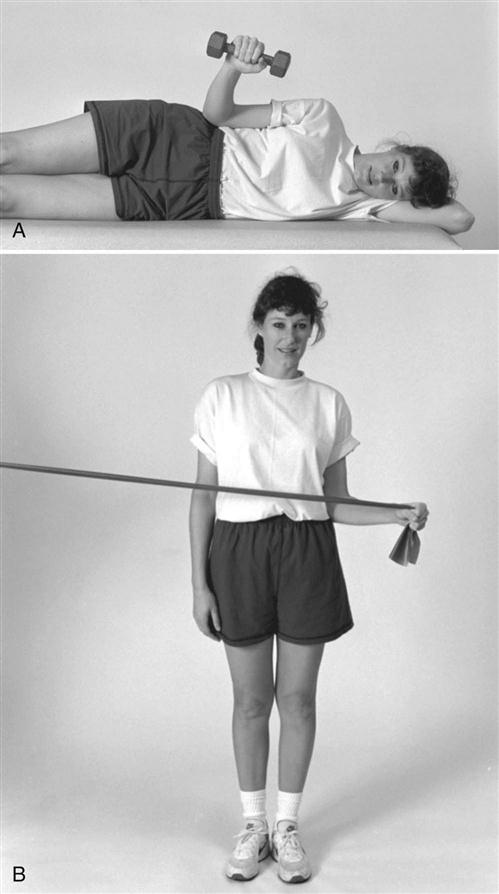

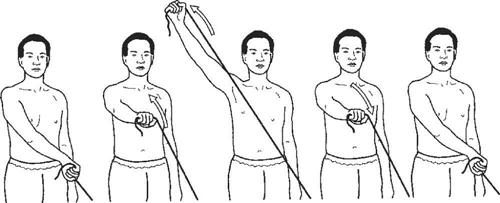

![]() Strength should begin to improve, with the patient progressing from PROM to active assistive range of motion (A/AROM) to AROM movements against gravity. A/AROM can begin at 6 weeks, and AROM can be initiated as able after 7 to 8 weeks. Submaximal isometrics can be initiated to eliminate neuromuscular inhibition, reiterate muscle firing, and retard muscle atrophy. The therapist can incorporate active assistive proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) D1 and D2 patterns to mimic functional movements and strengthen the areas in functional planes.15 In the D1 pattern, the shoulder moves into flexion-abduction-external rotation. With the D2 pattern, the shoulder moves into extension-adduction-internal rotation.21,41 Initiate these exercises in the supine position with the assistance of the therapist using PROM. Then progress to A/AROM in D1 and D2 patterns. Near the end of this phase, use independent performance of the PNF patterns in the supine position, advancing to a standing position when able. Eventually, active shoulder flexion, external rotation, and scaption exercises (Fig. 5-4) are performed after 7 weeks. Active shoulder flexion and scaption are usually initiated between zero and 70° (with the elbow bent at 90°) and progress according to the patient’s ability to execute these exercises correctly. Incorrect performance of shoulder elevation exercises can lead to impingement problems. Again evaluate for cervical spine (C/S) and thoracic spine (T/S) issues that may be causing secondary issues of pain and muscle tightness. Address joint or soft tissue issues.

Strength should begin to improve, with the patient progressing from PROM to active assistive range of motion (A/AROM) to AROM movements against gravity. A/AROM can begin at 6 weeks, and AROM can be initiated as able after 7 to 8 weeks. Submaximal isometrics can be initiated to eliminate neuromuscular inhibition, reiterate muscle firing, and retard muscle atrophy. The therapist can incorporate active assistive proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) D1 and D2 patterns to mimic functional movements and strengthen the areas in functional planes.15 In the D1 pattern, the shoulder moves into flexion-abduction-external rotation. With the D2 pattern, the shoulder moves into extension-adduction-internal rotation.21,41 Initiate these exercises in the supine position with the assistance of the therapist using PROM. Then progress to A/AROM in D1 and D2 patterns. Near the end of this phase, use independent performance of the PNF patterns in the supine position, advancing to a standing position when able. Eventually, active shoulder flexion, external rotation, and scaption exercises (Fig. 5-4) are performed after 7 weeks. Active shoulder flexion and scaption are usually initiated between zero and 70° (with the elbow bent at 90°) and progress according to the patient’s ability to execute these exercises correctly. Incorrect performance of shoulder elevation exercises can lead to impingement problems. Again evaluate for cervical spine (C/S) and thoracic spine (T/S) issues that may be causing secondary issues of pain and muscle tightness. Address joint or soft tissue issues.

![]() Precautions at this stage include no resisted exercises for 8 weeks. Between 6 and 12 weeks, advise patient to only perform waist level activities and no heavy lifting for 4 to 6 months. Marked increases in swelling, pain, or wound drainage (or the presence of red, streaking marks) must be reported immediately, and exercises should be discontinued.

Precautions at this stage include no resisted exercises for 8 weeks. Between 6 and 12 weeks, advise patient to only perform waist level activities and no heavy lifting for 4 to 6 months. Marked increases in swelling, pain, or wound drainage (or the presence of red, streaking marks) must be reported immediately, and exercises should be discontinued.

Phase III

TIME: 8 to 13 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Expansion of ROM, avoidance of impingement problems, gaining of near full ROM, increased strength, alleviation of pain, increased function, and decreased soft tissue restrictions and scarring (Table 5-3)

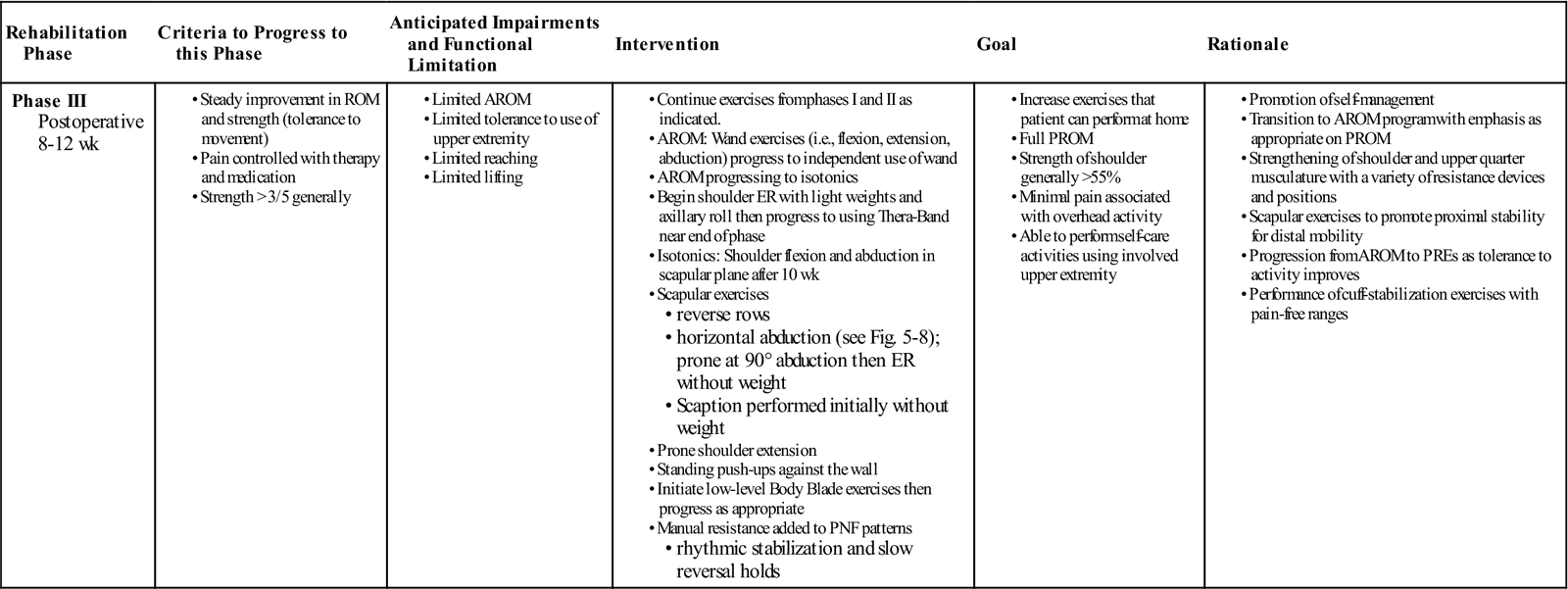

TABLE 5-3

Rotator Cuff Repair for Moderate-Sized Tears

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to this Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitation | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

|

Phase III Postoperative 8-12 wk

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

To advance to this phase, the patient should have minimal pain, near full ROM, and greater than three over five for strength generally throughout the shoulder movements. Often when progressing a patient to a new level of exercises (i.e., going from A/AROM to AROM) muscle soreness will be more pronounced initially. The patient will usually adapt to the new demands of the program within the first week.

During the period from 9 to 12 weeks after surgery, the patient should progress to full ROM. By 12 weeks the repaired tissues are now strong enough to tolerate stretching within the patient’s tolerance level. Passive stretching of the internal and external rotators is important. Tightness in these areas could promote abnormal shoulder mechanics, particularly in the throwing athlete. Tight external rotators lead to anterior translation and superior migration of the humeral head, which can produce impingement problems.54 ROM will normally progress without much difficulty.

AC joint pain is common in many patients who have undergone rotator cuff repair. The symptoms may result from a previous trauma, be caused by primary generalized osteoarthritis (OA), or follow abnormalities in the GH joint, such as degeneration and rupture of the rotator cuff.17 The AC joint will especially be tender if an acromioplasty was performed. When the AC joint is hypomobile and symptomatic, mobilization can help alleviate a portion of the symptoms and allow greater mobility (Fig. 5-5).

After the incision is healed and closed, the therapist can apply soft tissue mobilization over the incision areas and instruct the patient in massaging the scarred area. Early movement minimizes tightness from scarring. Normal skin mobility allows normal movement to occur.9

Resistance exercises are initiated around 10 weeks. Patients should demonstrate correct active movements before resistance is added in a particular range. The patient must perform the resisted exercises correctly or the movement needs to be altered. Isotonic exercises are important for strengthening and promoting dynamic shoulder stabilization. The humeral head stabilizers are used during this phase. The supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis muscles pull the humeral head securely into the glenoid and control humeral rotation so that the humeral head stays in good alignment with the glenoid.49 In addition, it should be noted that the primary depressors of the humeral head during shoulder elevation are the infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis muscles. Because the infraspinatus is involved in two critical force couples about the GH joint, the quality of shoulder motion is directly related to its function.52

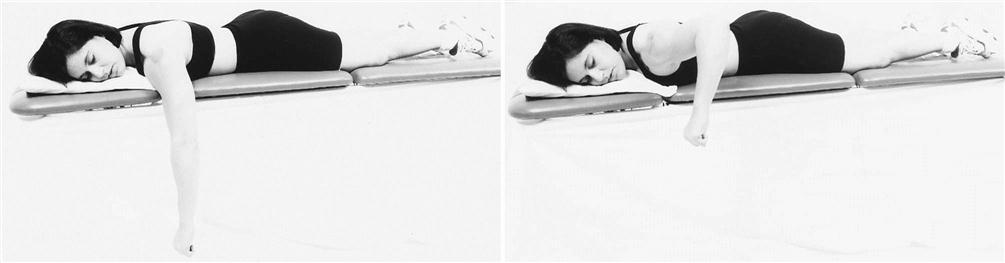

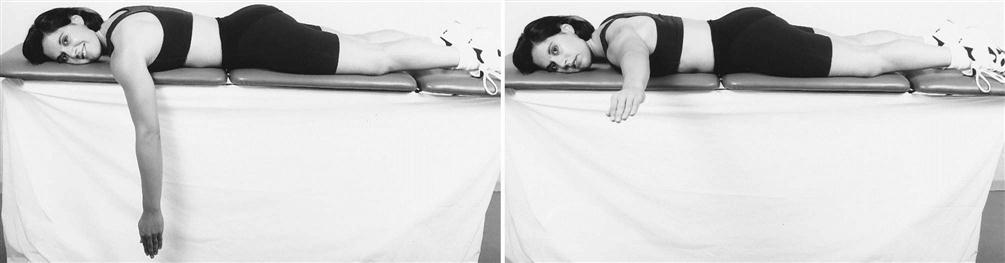

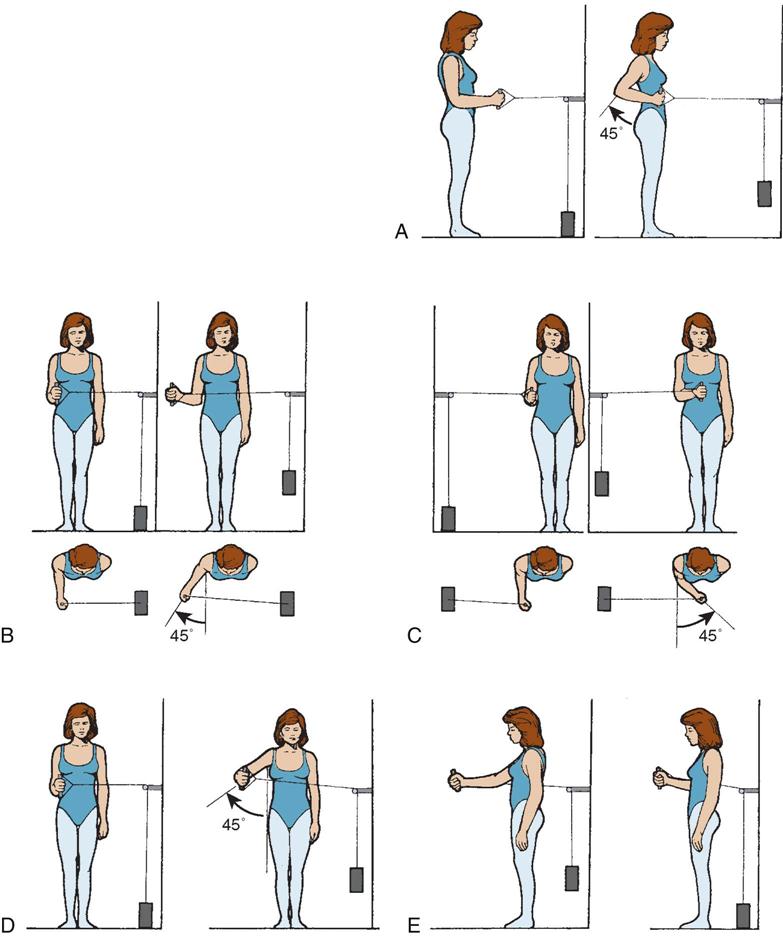

When resisted exercises are initiated, begin external rotation with hand-held weights with the patient in a side-lying position on the unaffected side. The elbow is maintained in 90° of flexion, and the patient starts with the shoulder in internal rotation, then moves into external rotation (Fig. 5-6, A and B). Eventually the patient can be progressed to concentric-eccentric movements using a Thera-Band for external rotation and internal rotation. An axillary roll can be placed under the shoulder to avoid a fully adducted position, which can cause a vascular stress on the supraspinatus and biceps tendon.10,26 Resisted elbow flexion exercises can be done with exercise tubing for the biceps. The long head of the biceps brachialis has been revealed as a strong humeral head depressor and acts to steer.52 Baylis and Wolf55 described a “four square” combination of tubing-resisted exercises for shoulder flexion, shoulder extension, internal rotation, and external rotation (see Fig. 5-6), followed by stretching of the external rotators and abductors.

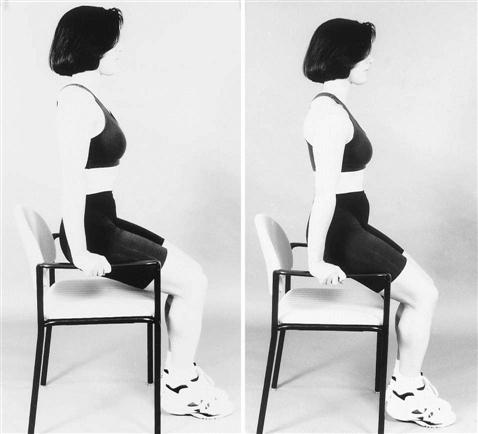

Remember that proximal stability is essential for controlling distal mobility.41 Moseley and associates56 reported that four exercises appeared to significantly enhance recruitment of the scapular muscles. These exercises included shoulder elevation in the scapular plane, upright rowing, a press-up, and a push-up with a “plus.”52 Shoulder flexion and abduction exercises in the scapular plane (instead of the straight planes) are more functional and less problematic to the rotator cuff. Prone rowing can also be done (Fig. 5-7). Rowing is excellent for all portions of the trapezius, levator scapula, and rhomboids. These muscles help maintain the scapula in good alignment during shoulder movements. The higher and the lower trapezius musculature stabilizes the scapula for overhead activities. In addition, prone horizontal abduction can be incorporated to strengthen the rhomboid major and minor and the middle trapezius muscles (Fig. 5-8).56 Dynamic hug exercises are a good way to begin strengthening the serratus anterior muscle. Progressive push-up exercises will strengthen the serratus anterior and the pectoralis minor muscles. A seated push-up with a plus was found to be effective in recruiting the serratus anterior with less activity of the trapezius musculature.56 At this stage patients should use their legs to assist themselves with the exercise (Fig. 5-9). Push-ups are initiated into the wall at this time; later they can be progressed to table height, then performed on the floor “ladies’ style,” and finally some patients are progressed to a complete push-up. Press-ups and seated push-ups are done with active patients. They can be initiated with support from the lower extremities and eventually progressed to only balance assisted by the lower extremities. These exercises help strengthen the serratus anterior muscle, which encourages humeral head depression with shoulder elevation. Older, more sedentary patients can strengthen their serratus anterior muscle using a Swiss ball (Fig. 5-10).

Resisted exercises also are performed in PNF patterns to strengthen the muscles in functional patterns. A frequently used pattern is the D2 pattern using both concentric and eccentric contractions. This is particularly effective in throwers. Manual resistance is again incorporated for rhythmic stabilization exercises and slow reversal hold techniques.21,41 If strength is not sufficient to overcome light resistance then begin with a hold pattern or a hold position in the weak area of the range. During rhythmic stabilization, the most commonly used angles are 30, 60, 90, and 140 of shoulder elevation.52 This movement will stimulate muscle contractions around the GH joint, promoting the joint force couples to work more efficiently and encouraging better dynamic stabilization of the humeral head.52 Good angles to work on with rhythmic stabilization are areas of increased weakness; therefore one can specifically strengthen at the weakest point, allowing improvement for the entire movement.

Strengthening begins with normalizing AROM while initiating light resistance into an appropriate arc of motion. AROM for shoulder elevation begins with the elbow flexed. The patient can add light resistance when he or she performs active elevation correctly with the elbow extended. Resistance may be added for elevation up to 70° of motion and progressed as the patient is able to perform AROM correctly through 80° and progressing to 150° of elevation. The patient must also demonstrate good scapular humeral mechanism without pain and perform 20 repetitions. This must be executed correctly before resistance is added.53 If challenged by 10 repetitions but able to do 20, then maintain the level of resistance. Do not train for power. The patient needs good muscle endurance over time, therefore do 30 repetitions before gradually increasing the load.53 When using resistance, begin abduction movement to 45°. Shoulder flexion can be performed between 70° and 80°. External rotation can be initiated in a supported position, then advanced to unsupported. When using a Thera-Band, have the patient begin with yellow and do 10 repetitions. If challenged and eager to rest, then go to another exercise. If easy then do 10 more repetitions. If still easy then do another set of 10 repetitions and move on. If the patient executes 30 repetitions well, the therapist may gradually increase resistance.53 Even today, the low intensity resistance, high repetitions technique may be the best regimen for athletes with injuries of insidious onset and during early rehabilitation phases.57 By 20 weeks, the athlete can advance to heavier weight lifting.48

In my experience, the Body Blade has been helpful for active patients. Exercises with the Body Blade are initiated with the shoulder and upper arm against the trunk. Eventually patients progress to operating the Body Blade with the arm extended away from the body and elevated. In even more advanced stages, patterns of motion can be followed while maintaining the oscillations of the blade and proper body mechanics. These exercises enhance contractions around a joint, increase strength, a increase proprioception, as well as improve coordination and increase endurance. The Body Blade has also been shown to produce greater scapular activity than traditional resistance techniques.58

Often times, older patients with fair tissue status and massive tears have difficulty progressing to active shoulder flexion against gravity. Eccentric shoulder flexion exercises without weights help provide these patients with a transition to active shoulder flexion. Help patients lift their arms in the scapular plane above their heads; then instruct them to lower their arms without allowing them to fall. These patients also need to emphasize strengthening of their humeral head depressors. Finally, have them exercise in front of a mirror so that they can readily correct the tendency to hike their shoulder.

Strengthening of the trunk and legs is important for athletes. Numerous studies indicate that the trunk and legs are responsible for more than 50% of the kinetic energy expended during throwing (see Chapter 13). Endurance training also begins during this phase. Patients begin on the upper body ergometer with short-duration and low-intensity bouts, and then they advance to longer durations and higher intensity bouts. Modalities are minimally used during this stage. Pain is generally minimal but will increase with moderate to dramatic changes in activity levels.

Precautions are necessary when initiating isotonic shoulder elevation exercises. All exercises should be performed with little or no joint pain. Complaints of muscle discomfort are acceptable and even desirable.19 ![]() However, if the patient complains of sharp pain through particular ranges, then the therapist needs to modify the exercises to avoid a painful arc.

However, if the patient complains of sharp pain through particular ranges, then the therapist needs to modify the exercises to avoid a painful arc.

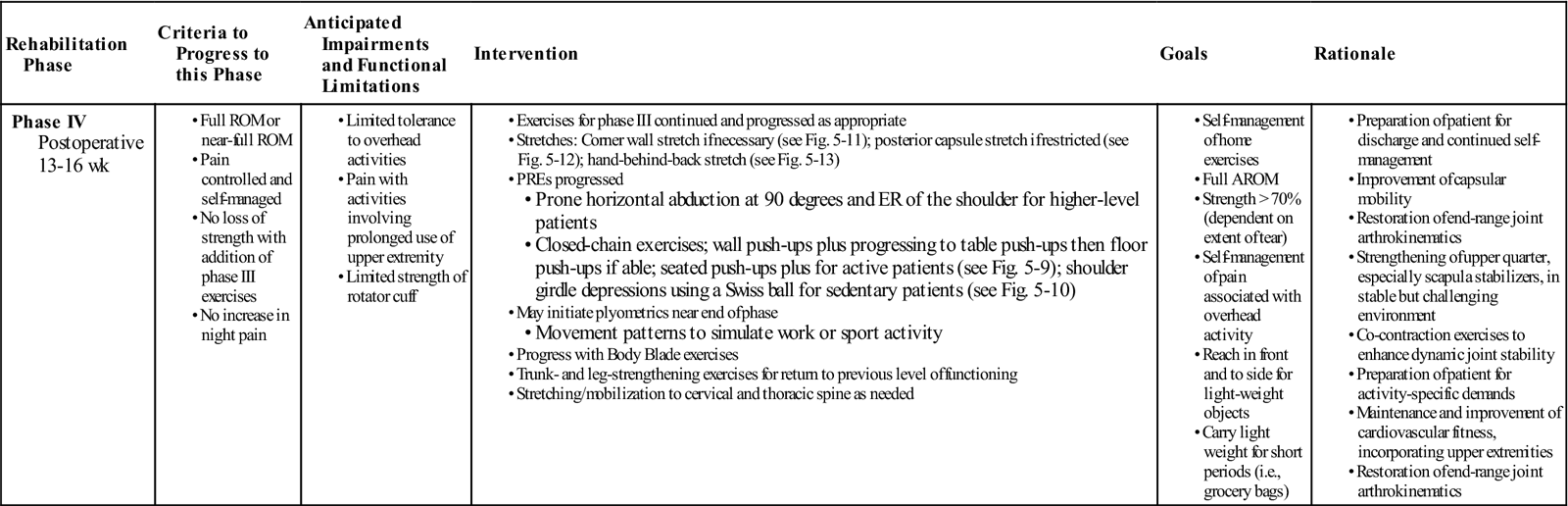

Phase IV

TIME: 13 to 16 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Maintenance of full ROM, increased strength and endurance, improved function (Table 5-4)

TABLE 5-4

Rotator Cuff Repair for Moderate-Sized Tears

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to this Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goals | Rationale |

|

Phase IV Postoperative 13-16 wk

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

The patient should have full ROM by 13 to 16 weeks. If this is not the case, then progressing with ROM needs to be the primary focus during treatments until this has been achieved. The therapist can emphasize more aggressive mobilization using grades +3 and +4 on the GH capsule to stretch the specific areas of capsular restrictions, thereby normalizing arthrokinematics at the GH joint. These mobilizations also can be performed near the physiologic end ROM, and they can be performed near end of ranges in conjunction with combined movements (refer to the question-and-answer scenario for an application example). Adequate capsule laxity is necessary to allow normal rolling and gliding between the bony surfaces of a joint. Patients should continue the necessary stretches to gain and maintain ROM in restricted areas (Figs. 5-11 through 5-13 illustrate some of the suggested stretches).

![]() It should be noted that with throwing athletes the anterior capsule does not need to be stretched as much. Patients with anterior instability issues should not exercise near extreme ranges of abduction and external rotation. Those with posterior GH instabilities should avoid extreme ranges of horizontal adduction and internal rotation.

It should be noted that with throwing athletes the anterior capsule does not need to be stretched as much. Patients with anterior instability issues should not exercise near extreme ranges of abduction and external rotation. Those with posterior GH instabilities should avoid extreme ranges of horizontal adduction and internal rotation.

If the patient cannot elevate the arm without shoulder hiking (i.e., scapulothoracic substitution), then continue to focus on the humeral head–stabilizing exercises and exercise the humeral head depressors. Remember the primary function of the rotator cuff is to provide good humeral head alignment with the glenoid fossa; this must be mastered before any complex movements are initiated. The efficiency of the GH force couples is vital for success. The primary couples of the GH joint are the subscapularis counterbalanced by the infraspinatus and teres minor and the anterior deltoid and supraspinatus counterbalanced by the infraspinatus and teres minor.

Strengthening exercises are progressed with progressive resistance exercises (PREs) progressing to 3 to 5 lb or the green Thera-Band if able. See Fig. 5-16 for exercises using the Thera-Band. The supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles (also known as decelerators) produce slow, controlled movements. These muscles are subjected to larger stresses and also are injured more frequently in overhead sporting activities.59 Through the use of electromyographic studies, Blackburn found that the best isolation for the infraspinatus and teres minor muscles occurs during prone exercises incorporating horizontal abduction and external rotation. An optimal exercise for athletes who need GH congruity and stability is prone external rotation with the shoulder at 90° abduction and the elbow flexed to 90°.60 These exercises should be performed at a functional speed starting without weight then adding resistance.61 Resisted external rotation with abduction is another good strengthening exercise for athletes.

Continue with push-ups while leaning into a wall and progress to ladies’ style push-ups if able. More active patients or athletes can progress to the standard push-ups on the floor, as previously mentioned. Closed-chain exercises help promote cocontractions and enhance dynamic joint stability.62

Therapists must also consider the neuromuscular system that provides joint stability through proprioceptive awareness, because proprioceptive training of the shoulder can lead to improved neuromuscular control, which can improve the overall dynamic stability of the GH joint.63 Appropriate shoulder exercises using the Body Blade provide proprioceptive training, dynamic-stabilization training, and endurance training. Eventually (during the later stages of rehabilitation) the patient can be progressed using the Body Blade through a vast range of shoulder movements, allowing athletes and workers to train and exercise in specific patterns or postures. These movements mimic a pattern of movement or a position used during a sport or work activity. In a later phase, resistance can be added to these movement patterns with the use of a Thera-Band (see Fig. 5-17). Caution must be used while progressing the patient from 10 to 18 weeks because pain is usually absent.

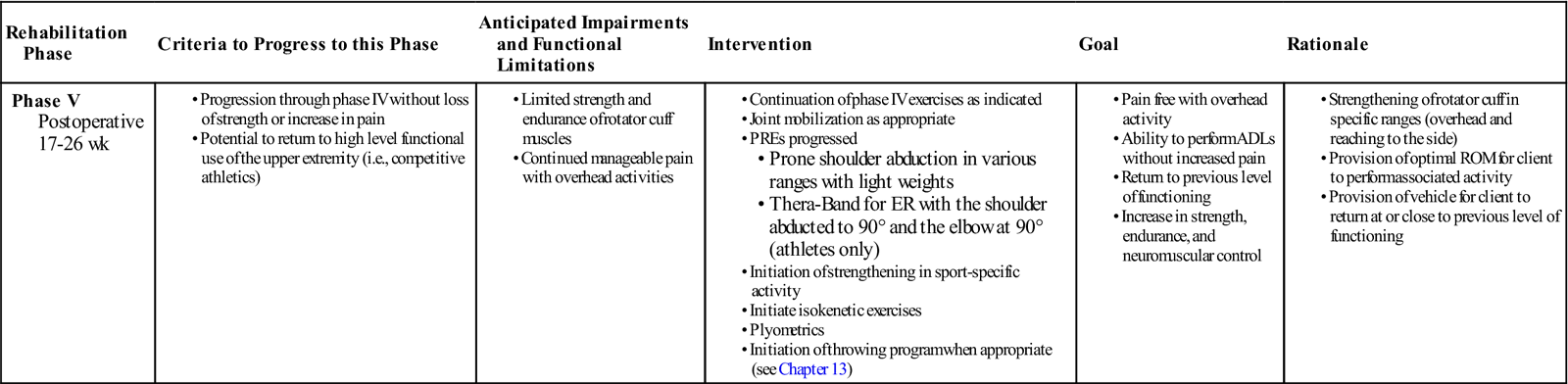

Phase V

TIME: 17 to 21 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Maintenance of full ROM, increased strength and endurance, improvement of neuromuscular control, return to functional activities, initiation of sport-specific activities (Table 5-5)

TABLE 5-5

Rotator Cuff Repair for Moderate-Sized Tears

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to this Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

|

Phase V Postoperative 17-26 wk

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

The therapist can continue the stretching program and instruct the patient in self-mobilization techniques if indicated. The patient can maintain a shoulder-strengthening program and continue PREs with increasing hand weights. Isokinetic training can also be beneficial. These exercises can be performed throughout the range because of the accommodation factor in isokinetic training. If a patient cannot move through the resistance at a particular arc of motion, he or she still can train with resistance throughout the whole range.

Athletes and other appropriate patients can begin plyometric exercises, which involve a stretch-shortening cycle of the muscle. Plyometrics can be performed two times a week. All sporting movements involve this explosive stretch-shortening cycle (e.g., jumping, throwing, running, swimming).45 Progressive plyometric exercises are done with appropriate patients who exhibit correct execution of the exercises. Recreational and competitive athletes perform exercises at higher speeds, using more eccentric muscle contractions and higher level progressions. These exercises are excellent intermediate steps between traditional strengthening exercises and training activities before initiating throwing drills.63

Resisted exercises using tubing with concentric-eccentric contractions, isokinetics, and scapulothoracic strengthening can be done. Athletes or workers required to do continuous overhead activities can perform exercises with a Thera-Band for external rotation, starting with an axillary pillow between the trunk and arm, then to the scapular plane position, and then to the 90°/90° position if able. D2 diagonal patterns can be executed with tubing. Latissimus strengthening and scapular retraction exercises can be performed using a Thera-Band.64 Athletes and higher level patients can perform these exercises at a faster and higher speed while maintaining control over the movement. They can also perform at a slower and more deliberate pace. Specific applications of eccentric training to the posterior cuff using a Thera-Band and/or isokinetics are essential to pitchers and ball players.

Later, when the patient is ready, initiate sport-specific drills for athletes along with an interval sports program (see Chapter 13). Throwing techniques need to be evaluated.

![]() If the patient is using bad body mechanics, using improper techniques while throwing, or both, then tissues may be overstressed, eventually causing rotator cuff problems once again. Older, sedentary patients should work on specific ADLs. As appropriate, patients may progress to more difficult tasks.

If the patient is using bad body mechanics, using improper techniques while throwing, or both, then tissues may be overstressed, eventually causing rotator cuff problems once again. Older, sedentary patients should work on specific ADLs. As appropriate, patients may progress to more difficult tasks.

In general golfers can usually start putting at 14 to 16 weeks and then progress as able. At 20 to 22 weeks tennis players can begin hitting their forehand and backhand strokes and progress to serving. And swimming can be initiated between 20 and 26 weeks. By 7 to 9 months the athlete may be able to reengage in sports activities competitively.

Phase VI

TIME: 22 and more weeks after surgery

GOAL: Return to normal activities, maintenance of full ROM, continued strengthening and endurance, gradual return to full activities. Athletes can return to their sports usually between 6 and 12 months

During weeks 22 to 26 patients maintain a stretching and strengthening program. Athletes continue on strengthening and on a sports interval program. Others gradually progress to recreational activities. Older individuals continue to progress with PREs and work on more advanced ADLs. The ability to return to more high-level activities ranges from 26 weeks to more than 1 year after surgery. After 26 weeks, patients continue with their stretching and strengthening program as long as they anticipate using the shoulder aggressively in ADLs or sports. The patient can maintain a shoulder-strengthening program and continue PREs with increasing hand weights up to 6 to 10 lb for athletes or 1 to 5 lb for more sedentary people. Isokinetic exercises may be initiated with athletes when they are able to lift 5 to 10 lb in external rotation and 15 to 20 lb in internal rotation without pain or significant edema.38 The patient should begin strength and endurance training at 200°/second.38,72

Troubleshooting

Considering influential factors outside the GH joint during treatment will aid the therapist in helping the patient progress more efficiently. General suggestions are given; however, it is beyond the scope of this book to instruct therapists in the use and application of techniques. The following areas are addressed:

Cervical Spine

Evaluation of the cervical spine may prove vital in addressing cervical issues that may be inhibiting progress. Although the cervical spine is not the primary cause of shoulder dysfunction when dealing with rotator cuff repairs, it may be a contributory factor. Often cervical spine disorders occur in conjunction with a traumatic shoulder injury (e.g., falling onto the upper extremity may cause injury to the shoulder and the cervical spine). Furthermore, prolonged muscle guarding secondary to the shoulder injury or pathology affects the cervical area. Muscles in spasm originating or inserting along the cervical spine can lead to cervical symptoms. Thus a patient may have a combination of cervical and shoulder signs and symptoms. Treatment to the appropriate cervical joints can alleviate a portion of the symptoms and signs, thereby decreasing the complaints of pain and potentially allowing more GH movement and function. Clinicians may notice that after treating cervical spine dysfunctions, treatment of the shoulder is more effective.

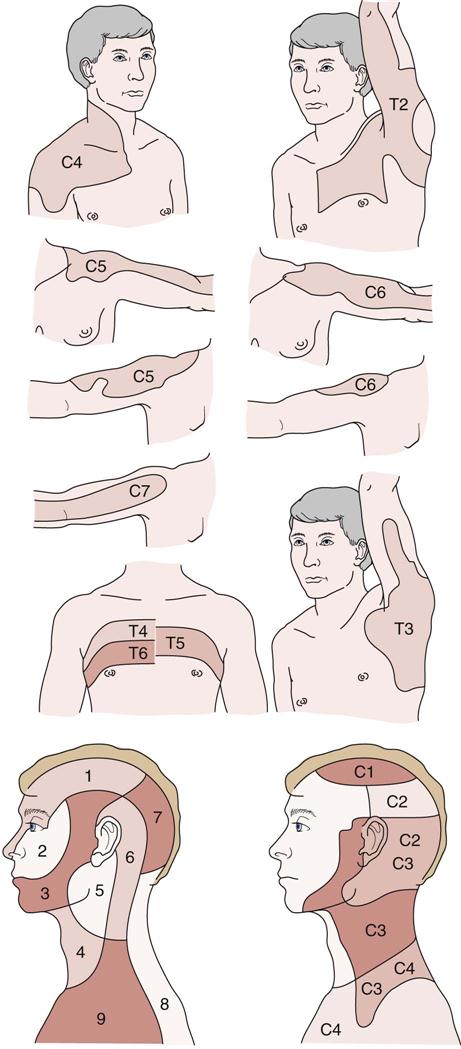

Common patterns in cervical pathology are addressed to assist clinicians with differentiating shoulder and cervical symptoms because they frequently occur together. Spinal disorders may cause referred pain (Fig. 5-14). Joint movement disorders may cause joint pain and be associated with an altered range of cervical spine joint movement or shoulder movement. Therefore the cervical spine should be assessed for additional joint disorders that may be causing local pain or pain that is referred into the shoulder and arm region.32 (Suggested readings for treatment of the cervical spine are Practical Orthopedic Medicine by Corrigan and Maitland32 and Vertebral Manipulation by Maitland.36)

Thoracic Spine

Thoracic mobility affects shoulder mobility. During unilateral shoulder flexion, contralateral side flexion of the spine occurs; bilateral shoulder flexion produces spinal extension.22 Therefore decreased thoracic extensibility or increased thoracic kyphosis can inhibit shoulder ROM.65

Postural education is important, especially with patients who can voluntarily correct and maintain good posture. Maintaining an erect posture while performing upper extremity activities allows greater ROM at the shoulders. Better posture decreases the amount of impingement, which a patient can see in the following maneuver:

1 Have the patient flex the shoulder through its available ROM while in a seated slouched position.

2 Ask the patient to flex the shoulder while seated with good posture.

The patient will be able to lift the arm higher when maintaining a more upright posture. A slouched position causes depressed forward-displaced shoulders and GH internal rotation. The potential for shoulder impingement increases with this type of posture.65

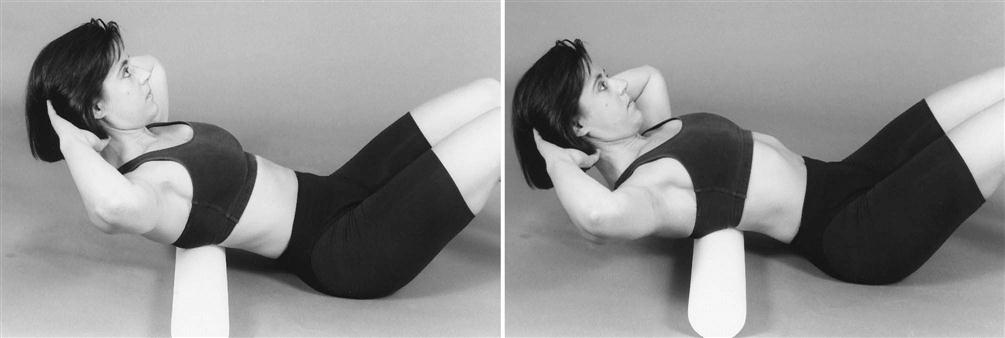

Evaluation and treatment of the thoracic spine may prove helpful for patients having difficulty progressing in ROM in the latter stages. Addressing issues of hypomobility and decreased ROM of the thoracic spine and treating them appropriately allows for better progress. Mobilization of a hypomobile thoracic spine and ROM exercises to increase thoracic extension (e.g., supine on a Swiss ball) can be beneficial. A foam roll also may be used when appropriate to increase thoracic spinal extension and mobility (Fig. 5-15). (Vertebral Manipulation36 offers instruction on evaluation and treatment of the thoracic spine.) With regard to positioning, the therapist also must consider protection of the shoulder and the surgery site.

If complaints of pain persist in the cervical spine region, then assess for contributing factors arising from the thoracic spine. Mobilization to a stiff thoracic spine (if warranted) may alleviate some or all of the cervical pain that continues to persist.66

Adverse Neural Tension

The nervous system can be directly mobilized through tension tests and their derivatives.40 Adhesions in neural tissue can affect shoulder movement and strength, and may influence the patient’s progress. However, the therapist must be aware of any precautions or contraindications. A good evaluation is necessary for addressing adverse neural tension issues. Neural tissue mobilization can be effective when used with appropriate patients to help relieve some of the symptoms and potentially improve ROM and strength. These issues may be better addressed during the latter phases of rehabilitation when the tissue repair has healed and shoulder ROM is only minimally limited or not restricted. Clinicians trained in neural tissue mobilization should only perform treatment to the nervous system. Avoid placing a stretch on the nerves.

![]() The objective is to move the nerves, mobilizing them without stretching them. Increase in symptoms such as pain, numbness, tingling, and paresthesias down the arm may indicate the nerves are being stretched.73

The objective is to move the nerves, mobilizing them without stretching them. Increase in symptoms such as pain, numbness, tingling, and paresthesias down the arm may indicate the nerves are being stretched.73

Acromioclavicular Joint

OA in the AC joint is not uncommon.67 It may result from previous trauma or be part of a primary generalized OA, impingement, or capsulitis. OA in the AC joint also may follow other abnormalities in the GH joint (e.g., degeneration and rupture of the rotator cuff) that allow the head of the humerus to sublux upward.32 In our experience, many patients with repaired and unrepaired rotator cuff tears have some symptoms arising from the AC joint.

Because the movement of all of the joints affects the shoulder complex, it is essential to evaluate and treat the entire shoulder complex to improve upper extremity function.68 Table 5-6 shows some of the joint movements that occur within the shoulder complex. Restrictions in one area will affect other areas of the shoulder complex.

TABLE 5-6

Shoulder Complex—Range and Axis of Motion*

| Joint Motion | Range (Degrees) | Axis of Motion |

| Sternoclavicular rotation (counterclockwise) | 0-50 | Longitudinal axis of clavicle |

| Glenohumeral (GH) flexion | 0-180 | Coronal through |

| Abduction | 0-180 | Sagittal through |

| Horizontal adduction | 0-145 | GH joint Vertical through GH joint |

| Internal rotation | 0-90 | Vertical axis through |

| External rotation | 0-90 | Shaft of humerus |

| Acromioclavicular (AC) winging of scapula | 0-50 | Vertical axis through AC joint |

| Abduction of scapula | 0-30 | Anteroposterior axis |

| Inferior angle of scapula tilts away | 0-30 | Coronal axis from chest wall |

| Scapulothoracic | ||

| Upward rotation | 0-60 | From 0-30° near vertebral border on spine of scapula; from 30-60° near acromial end of spine of scapula |

*When conflicting information occurred, the most frequently cited numbers were used.

Complaints of AC joint pain are usually localized over the joint. An active movement that may best implicate this joint as a source of pain is horizontal adduction of the arm across the chest. The therapist may determine whether the AC joint is hypomobile or hypermobile by passive accessory movement tests of the joint.69 If the AC joint is stiff and tender, then its mobilization often relieves a portion of the symptoms and promotes better shoulder ROM. The AC joint may also be tender from an acromion osteotomy if performed with the rotator cuff. Eventually gentle movements of the AC joint may be beneficial when the patient can tolerate the treatment. If the AC joint has been removed because it is arthritic or symptomatic then do not attempt to mobilize the area.

Accessory movements can be applied to the clavicle or acromion. When applied to the clavicle, they affect only the AC joint; however, when applied to the acromion, they affect both the AC and GH joint.6 Accessory AC joint movements should be used within the limits of pain. To increase motion at the AC joint, the therapist can use an anterior glide to the acromion through the posterior spine of the scapula while stabilizing the midclavicle. This allows mobilization of the AC joint without direct manual pressure over the joint or inflamed tissues.

As the available shoulder ROM progresses, this same technique can be applied with the shoulder in some degree of available flexion or in horizontal adduction (see Fig. 5-5).

Corrigan and Maitland32 describe a similar technique for the AC joint. In this method an anterior-posterior movement is produced by applying pressure over the anterior surface of the outer third of the clavicle with counter pressure along the spine of the scapula.

Sternoclavicular Joint

Degenerative changes are not found as commonly in the SC joint as in the AC joint but may occur as the result of trauma or overuse of the shoulder.70 Movements such as shoulder abduction or flexion may increase pain originating from this joint because of rotation of the inner end of the clavicle. SC joint pain is usually localized to the SC area, but it may radiate to other areas. Signs that implicate the SC joint as a contributing factor include reproduction of pain with horizontal flexion and passive accessory movements of the SC joint. The capsule and surrounding ligaments are likely to be thickened and tender.69

Treatment of the SC area includes rest, modalities, and mobilization, depending on the condition of the joint.32 A hypomobile SC joint may be correctly mobilized in several ways depending on its restrictions. To increase shoulder elevation, a caudal glide to the proximal clavicle can be used.32,37

Scapulothoracic Joint

Scapular muscles have been included in the rotator cuff repair protocol. However, some patients require more intense conditioning of these muscles. The scapula moves with concentric-eccentric motions. Patients with poor eccentric control of the scapular stabilizers demonstrate scapula winging on the return from full shoulder flexion. The serratus anterior is essential for stabilizing the medial border and inferior angle of the scapula, preventing scapula internal rotation (winging) and anterior tilt.60 These same patients may have full ROM and normal movement during flexion. If muscle weakness is apparent, then ensuring normal muscle strength around the scapulothoracic and GH joints is the goal. If the scapular muscles are weak and overstretched, then scapular motion during arm elevation may result in excessive lateral gliding of the scapula. Abnormal scapular muscle firing patterns, weakness, fatigue, or injury causes the shoulder to function less efficiently and the risk of injury increases.60

The therapist can use various PNF techniques, such as scapular slow reversal holds, rhythmic stabilization, and timing for emphasis, to intensify the dynamic control and kinesthesia of the scapulothoracic joint. Other recommended exercises are scapular protraction, retraction, elevation, and depression against manual resistance.71

Exercises are encouraged that enhance dynamic control of the scapulothoracic musculature.71 These should be directed to the scapular rotator muscles (i.e., the serratus anterior, rhomboid, trapezius, levator scapula) to position the glenoid and coracoid appropriately for the humerus. Exercises that mimic the rowing motion and shoulder horizontal abduction are both excellent for all portions of the trapezius and for the levator scapulae and rhomboid muscles. Flexion and scaption (i.e., scapular plane elevation) exercises are valuable for most of the scapular muscles (see Fig. 5-4). In addition, shoulder shrugs and press-ups with a plus are essential exercises for the levator scapula, upper trapezius, serratus anterior, and pectoralis minor muscles. Also refer to the “Prone Program Plus” for more exercise ideas.

Summary

The general guidelines described in this chapter help guide therapists and provide treatment ideas. Rotator cuff repairs vary in size from small to massive. The condition of the torn tissue and the joints (i.e., AC, GH) varies. Along with these differences, therapists must consider the patient’s unique history, profile, and abilities. They must consider each case and choose the treatment ideas that will work best, constantly assessing the patient’s responses. Therapists must always address the individual when deciding on a treatment plan.

Clinical Case Review

1 Paul just had a rotator cuff repair 3 days ago and says he can hardly sleep because of the pain. How can you advise him so that he gets more sleep during the night?

Encourage patient to take pain medications as prescribed. Time the medication so that it is most effective at bed time. Advise patient to sleep in a recliner or a semireclined position in bed. The shoulder should be placed in a loose packed position using pillows or cushions. Demonstrate this for the patient. Also encourage patient to use cold packs around the shoulder and neck area. During the treatment, mobilize the stiff C/S joints and mobilize tight soft tissue around the cervical area emphasizing the area near the affected shoulder. Finally, mobilize the GH joint using grades I and II.

2 Jim is a 38-year-old weekend athlete who sustained a large rotator cuff tear after falling onto an outstretched arm during a flag football game. At 3 weeks after rotator cuff repair surgery, he complains of moderate shoulder pain that radiates through the upper trapezius area and into the superior medial scapular area. Jim also complains of neck stiffness that has worsened over the past few days. He remains guarded through most of his range when performing PROM. During today’s session, what areas should the therapist address to improve the quality of movement and increase the ROM?

The cervical spine needs to be assessed to determine whether it may be contributing to some of the patient’s complaints, particularly the neck stiffness and the superior medial scapular pain. If cervical spine joint stiffness or soft tissue tightness is noted, then appropriate joint or soft tissue mobilizations may decrease these symptoms. As pain decreases, muscle guarding will lessen, allowing the shoulder to move more freely.

3 Brent is a 27-year-old who had a rotator cuff repair for a large tear. He has progressed nicely with PROM. At 9 weeks after surgery, Brent can elevate his arm above his head with little effort. However, he demonstrates a mild shoulder hike with elevation above 70°. How much weight should Brent begin lifting when performing elevation exercises to 70°?

Brent should not lift any weights above 70° during shoulder elevation until he can execute the exercise correctly. He should practice maintaining voluntary humeral head depression with active elevation in front of a mirror. He should only do resisted exercises through the range he can correctly perform. Brent needs to strengthen the muscles that depress the shoulder while maintaining the humeral head in good alignment with the glenoid (rotator cuff muscles and serratus anterior). When he can elevate the arm correctly above 70°, he can begin adding weight for resisted elevation above 70°.

4 Rebecca had an RCR 10 weeks ago. Recently she has been complaining of an intermittent pain that travels from the lateral border of the AC joint down the lateral side of the arm into the mid forearm. This usually occurs when reaching over head or to the side, but will occur with different movements as well. On occasion she complains of this intermittent pain at rest with a decrease of intensity. What do you need to evaluate during today’s treatment?

The AC joint should be evaluated. Cervical joints C5, C6, and C7 along with their facet joints should be checked. Neural tension signs and soft tissue need to be addressed. Finally, the elbow needs to be assessed.

During the evaluation, adverse neural tension signs were positive and reproduced pain in the area of complaint. Neural mobilization techniques were performed and the intensity and frequency of symptoms dramatically decreased.

5 Barbara is a 68-year-old woman who had a massive rotator cuff repair 12 weeks ago. Her favorite hobby is making jewelry. To work with the jewelry she needed to make a sawing motion with her affected (right dominant) arm. At this point the patient had −3/5 strength for flexion and abduction. She exhibited +3/5 for external rotation and −4/5 for internal rotation. The patient did not have the strength to make this sawing motion against much resistance throughout the range. She was weak, and her endurance was low. Tissue status was fair. How should the therapist exercise this patient?

Patient had full PROM throughout the affected shoulder. The therapist mostly performed manual assisted and resisted exercises with this patient to maximize strengthening at her weakest points in the range. The therapist performed PNF patterns for the upper extremity and the scapular muscles. Manual resisted exercises for serratus anterior strengthening and rotation strengthening. Resisted shoulder depression exercises were also done. In addition, rhythmic stabilization was used. Shoulder eccentric lowering was done for shoulder flexion strengthening because she could not perform AROM shoulder flexion against gravity (AROM shoulder flexion to 30° before initiating a shoulder hike). Manual exercises with light resistance were done (and progressed) to mimic the sawing motion used with making jewelry. Surprisingly the patient did return to making jewelry after 5 to 6 weeks of exercising in physical therapy, along with home exercises. This patient was motivated and compliant.

6 Ruth is a 65-year-old sedentary female who had an RCR 10 weeks ago. She continues to demonstrate a moderate shoulder hike with elevation above 70°. What exercises need to be emphasized to eliminate this movement dysfunction?

Exercising the muscles that promote shoulder depression with elevation is critical. These muscles would include the rotator cuff, especially the infraspinatus muscle. The serratus anterior also keeps the humeral head depressed with elevation and the biceps help to keep the humeral head in place. Because Ruth is an older sedentary woman, she would have more success initially with the “shoulder girdle depression exercises using a Swiss ball.” Other exercises are mentioned in the chapter. Having her elevate her arm in front of a mirror while she concentrates on maintaining a depressed shoulder is also very helpful. Exercising the shoulder flexors in eccentric contractions also proved helpful.

7 Christine is a young mother who had a rotator cuff repair 6 months ago. She is returning to therapy because of stiffness issues in her shoulder. Her main complaints are reaching behind to grasp objects. Particularly difficult to reach toward the back seat of the car, which she needs to do frequently (small children in the back seat). She also would like to clasp her bra from the back. Upon evaluation she exhibited minimal restrictions for shoulder flexion and shoulder abduction near the end of the ranges. Shoulder internal rotation and extension were also limited, but the combined movement of internal rotation and extension with hand-behind-the-back movements was the most restricted. The patient’s thumb actively reached to T11 behind the back. What types of mobilization techniques would be particularly helpful?

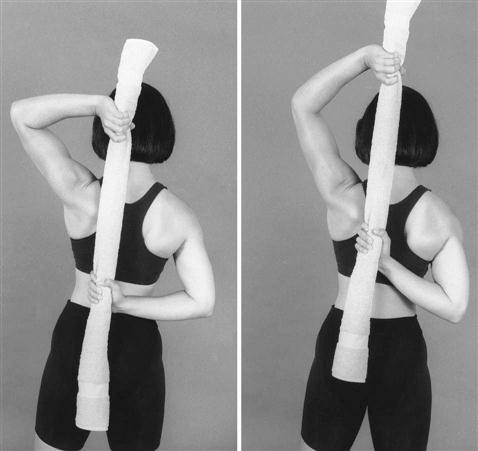

Mobilizations were performed in various areas of the capsule to improve all functional ranges. Mobilizations were also done near end ranges with combined movements using grades 3 and +4 to improve her hand-behind-the-back motions. The patient used her unaffected upper extremity to hold her other hand behind her back while the therapist applied a posterior-anterior force to the superior humerus. This was done to stretch the anterior capsule of the GH joint near its end range of combined movement. This was followed by the hand-behind-the-back stretch using a towel as shown in Fig. 5-13. The patient’s range improved dramatically after two treatments with the execution of home exercises that reinforced the hand-behind-the-back movements.

8 Yvonne is a 55-year-old female who had an RCR for a 5 cm tear. She had surgery 4 weeks ago and has been immobolized in a sling since surgery. She is coming to you for her first visit. Her physician wants her to use the sling for another week to 2 weeks. Should this be a concern regarding her rehabilitation program?

If the patient demonstrates greater than l20° with shoulder flexion without a leathery or hard end feel then she should progress normally with ROM in therapy while using the sling for another 2 weeks. However, if she has a history of shoulder capsulitis, or stiff joints after surgery or injuries, or the ROM is limited to less than 120° of elevation with PROM, then the therapist may want to make the physician aware of these concerns.