Chapter 15 Rotational and Free Flap Closure of the Abdominal Wall ![]()

1 Preoperative Considerations

1 Comorbidities

2 Open Wound Management

Appropriate dressings should be applied to the wound before surgery to prevent desiccation of the soft tissues and intraabdominal contents.

Appropriate dressings should be applied to the wound before surgery to prevent desiccation of the soft tissues and intraabdominal contents. Negative pressure dressings allow for easier management of large abdominal wounds, but the wound must be monitored closely when the dressing is applied over exposed bowel.

Negative pressure dressings allow for easier management of large abdominal wounds, but the wound must be monitored closely when the dressing is applied over exposed bowel.3 Timing

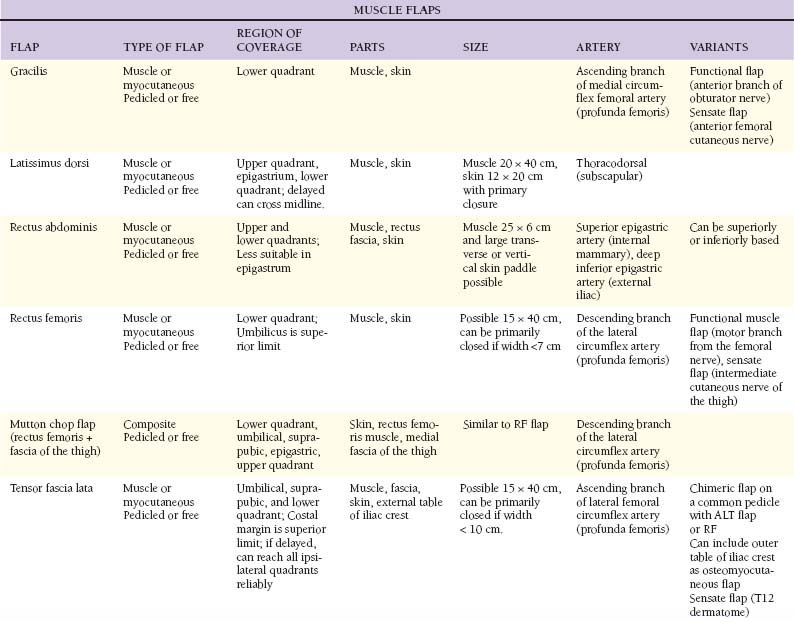

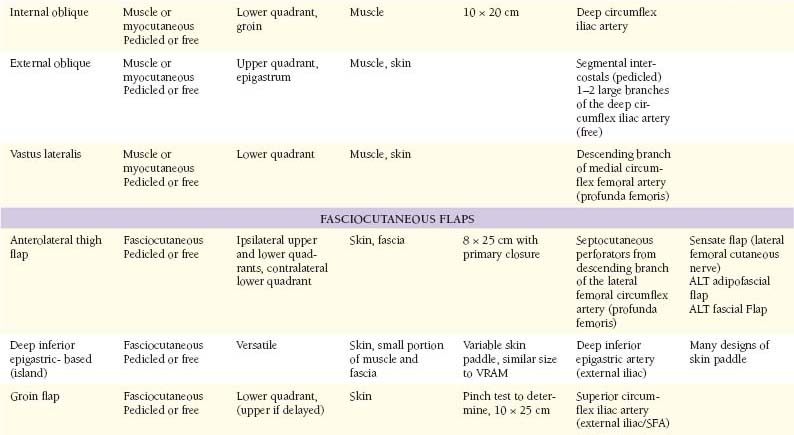

2 Muscular Flaps (Table 15-1)

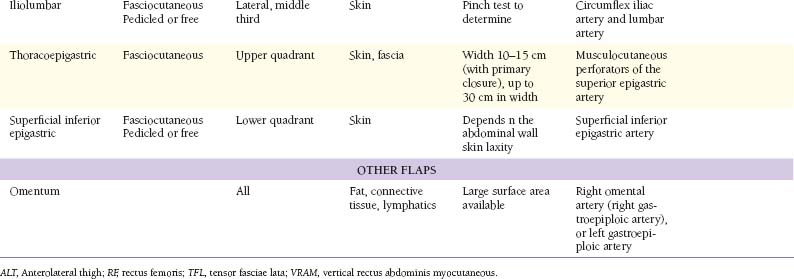

Figure 15-1 shows the cross-sectional anatomy of the thigh demonstrating the possible muscles for coverage of abdominal wall defects

Figure 15-1 shows the cross-sectional anatomy of the thigh demonstrating the possible muscles for coverage of abdominal wall defects1 Tensor fascia lata

Anatomy

Anatomy

Sensory innervation includes the lateral cutaneous branch of the twelfth thoracic nerve and the lateral cutaneous sensory nerve of the thigh (L2 and L3). Motor innervation is supplied by the distal branch of the superior gluteal nerve (L4 and L5).

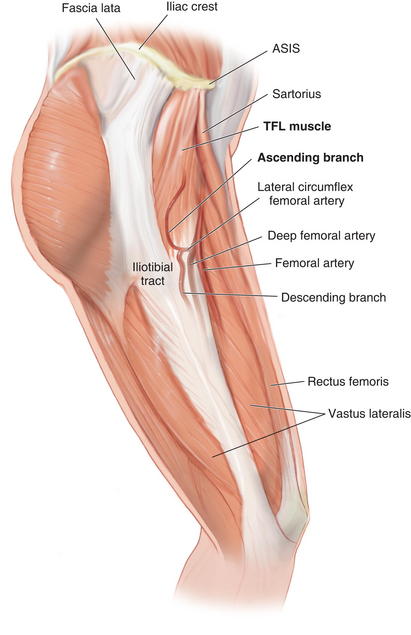

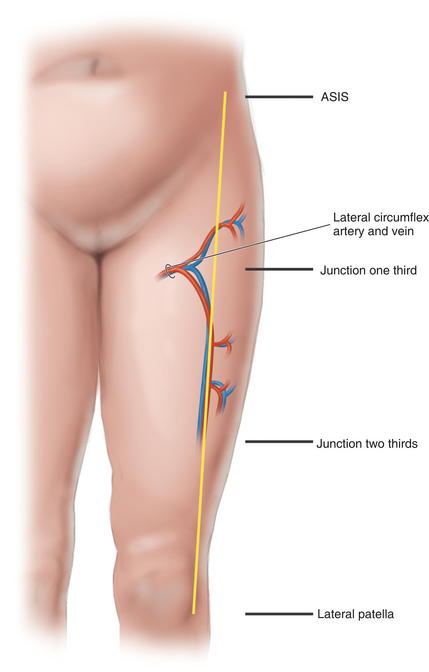

Sensory innervation includes the lateral cutaneous branch of the twelfth thoracic nerve and the lateral cutaneous sensory nerve of the thigh (L2 and L3). Motor innervation is supplied by the distal branch of the superior gluteal nerve (L4 and L5). Arterial blood supply is from the ascending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery, which is 1.5 to 2.5 mm diameter. The vein is slightly larger than the artery when traced to the origin on the lateral femoral circumflex.

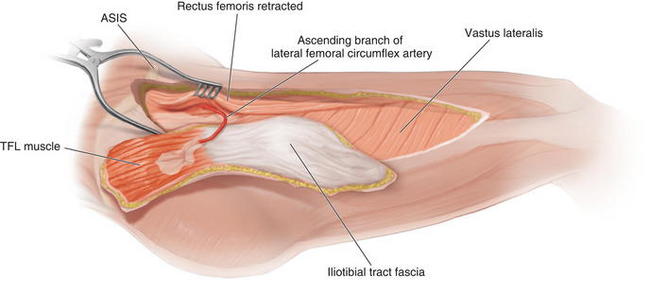

Arterial blood supply is from the ascending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery, which is 1.5 to 2.5 mm diameter. The vein is slightly larger than the artery when traced to the origin on the lateral femoral circumflex. Pedicle length can be up to 10 cm. The pedicle enters the tensor fasciae lata (TFL) muscle at the level of the junction of the proximal and middle thirds of an axis drawn from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the lateral aspect of the patella. It emerges from beneath the rectus femoris muscle, anterior to the vastus lateralis and enters the muscle via the deep surface medially 6 to 8 cm from the ASIS.

Pedicle length can be up to 10 cm. The pedicle enters the tensor fasciae lata (TFL) muscle at the level of the junction of the proximal and middle thirds of an axis drawn from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the lateral aspect of the patella. It emerges from beneath the rectus femoris muscle, anterior to the vastus lateralis and enters the muscle via the deep surface medially 6 to 8 cm from the ASIS. The descending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery continues beyond the TFL muscle to supply the skin of the anterolateral midthigh and the lower thigh. It can be harvested with the anterolateral thigh skin to enlarge the perfused vascular territory.

The descending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery continues beyond the TFL muscle to supply the skin of the anterolateral midthigh and the lower thigh. It can be harvested with the anterolateral thigh skin to enlarge the perfused vascular territory. The TFL muscle (Fig. 15-2) is a short, flat muscle that is approximately 12 to 15 cm long. It acts as an accessory flexor and medial rotator of the thigh. It originates from the anterior iliac crest and the deep surface of the fascia lata. At the origin, it lies between the gluteus medius and sartorius, and superficial to the vastus lateralis. It inserts into the iliotibial tract, which inserts distally on Gerdy’s tubercle on the lateral aspect of the tibia.

The TFL muscle (Fig. 15-2) is a short, flat muscle that is approximately 12 to 15 cm long. It acts as an accessory flexor and medial rotator of the thigh. It originates from the anterior iliac crest and the deep surface of the fascia lata. At the origin, it lies between the gluteus medius and sartorius, and superficial to the vastus lateralis. It inserts into the iliotibial tract, which inserts distally on Gerdy’s tubercle on the lateral aspect of the tibia. The fascia lata is the deep fascia of the thigh. It thickens to form the iliotibial tract laterally and attaches distally to the lateral condyle of the tibia. The TFL muscle is enclosed by the fascia lata, and distally, the muscle fibers coalesce with the iliotibial tract in the middle third of the thigh. The thickness of the fascia lata over the TFL muscle makes it a strong fascial donor site suitable for reconstructing abdominal wall defects.

The fascia lata is the deep fascia of the thigh. It thickens to form the iliotibial tract laterally and attaches distally to the lateral condyle of the tibia. The TFL muscle is enclosed by the fascia lata, and distally, the muscle fibers coalesce with the iliotibial tract in the middle third of the thigh. The thickness of the fascia lata over the TFL muscle makes it a strong fascial donor site suitable for reconstructing abdominal wall defects. Flap Design

Flap Design

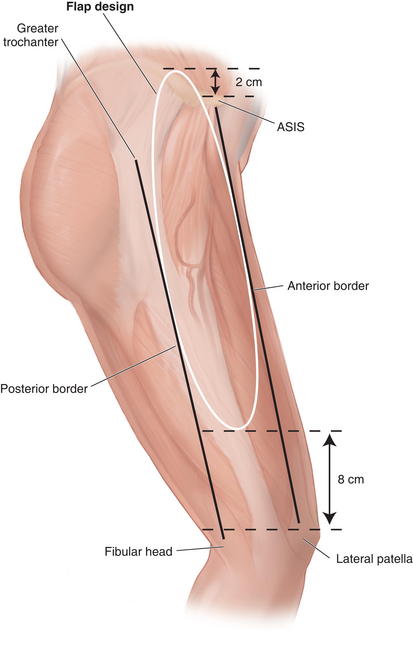

Skin territory can be up to 15 × 40 cm. A line from the ASIS 10 to 15 cm posteriorly marks the origin of the TFL muscle, with the skin territory extending 2 cm cranial to this line (Fig. 15-3). The lower skin territory is 8 cm above the lateral femoral condyle. Posterior skin territory is a line drawn from the greater trochanter to the fibular head or approximately along the axis of the femur. The anterior border is a line drawn from the ASIS to the lateral aspect of the patella.

Skin territory can be up to 15 × 40 cm. A line from the ASIS 10 to 15 cm posteriorly marks the origin of the TFL muscle, with the skin territory extending 2 cm cranial to this line (Fig. 15-3). The lower skin territory is 8 cm above the lateral femoral condyle. Posterior skin territory is a line drawn from the greater trochanter to the fibular head or approximately along the axis of the femur. The anterior border is a line drawn from the ASIS to the lateral aspect of the patella. The entry point of the pedicle is at the level of the junction of the proximal and middle third of the line or 6 to 8 cm from the ASIS.

The entry point of the pedicle is at the level of the junction of the proximal and middle third of the line or 6 to 8 cm from the ASIS. Marking and Dissection

Marking and Dissection

The flap is marked as an ellipse over the axis of the TFL muscle and to incorporate the pedicle proximally.

The flap is marked as an ellipse over the axis of the TFL muscle and to incorporate the pedicle proximally.2 Latissimus dorsi

The latissimus dorsi is the largest muscle in the body (up to 20 × 40 cm), but it is quite thin (<1 cm thick). It acts as a humeral adductor and internal rotator, and no significant functional deficit results from harvest. It has six origins, from the lower six thoracic spines and supraspinatus ligaments, posterior layer of lumbar fascia, tendinous attachments of the iliac crest, strips of muscle interdigitating with the external oblique, muscular slips from lower four ribs, and muscular slips from the scapula. The upper and anterior borders are free. The latissimus is deep to the trapezius. It inserts at the floor of bicipital groove of the humerus behind the tendon of the long head of the biceps. The latissimus forms the posterior fold of the axilla with the subscapularis tendon.

The latissimus dorsi is the largest muscle in the body (up to 20 × 40 cm), but it is quite thin (<1 cm thick). It acts as a humeral adductor and internal rotator, and no significant functional deficit results from harvest. It has six origins, from the lower six thoracic spines and supraspinatus ligaments, posterior layer of lumbar fascia, tendinous attachments of the iliac crest, strips of muscle interdigitating with the external oblique, muscular slips from lower four ribs, and muscular slips from the scapula. The upper and anterior borders are free. The latissimus is deep to the trapezius. It inserts at the floor of bicipital groove of the humerus behind the tendon of the long head of the biceps. The latissimus forms the posterior fold of the axilla with the subscapularis tendon. Blood Supply

Blood Supply

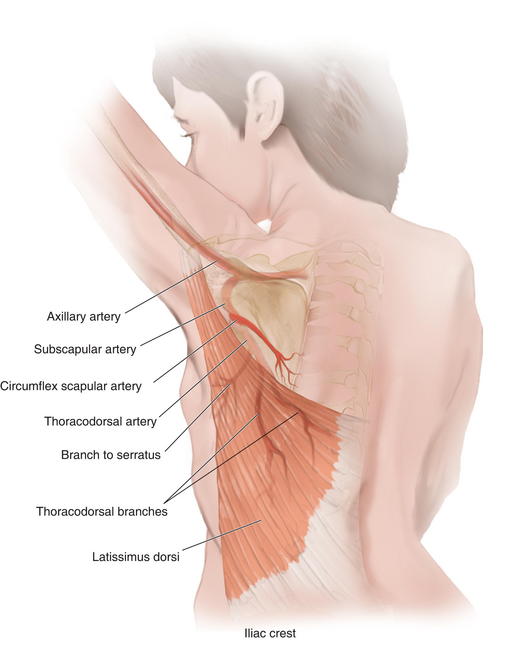

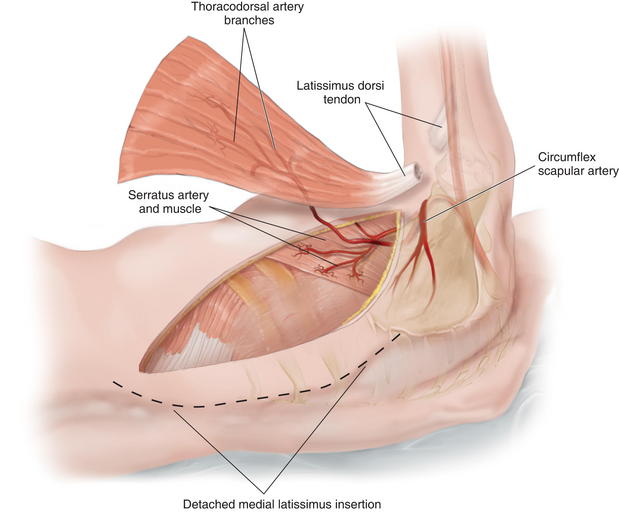

Arterial blood is supplied through a terminal branch of the subscapular artery (2 to 5 mm diameter), a branch of the axillary artery.

Arterial blood is supplied through a terminal branch of the subscapular artery (2 to 5 mm diameter), a branch of the axillary artery. After 5 cm, the subscapular artery gives off the circumflex scapular branch posteriorly and the thoracodorsal artery (2 to 4 mm diameter) (Fig. 15-5).

After 5 cm, the subscapular artery gives off the circumflex scapular branch posteriorly and the thoracodorsal artery (2 to 4 mm diameter) (Fig. 15-5). The thoracodorsal artery courses along the posterior aspect of the axilla for 8 to 14 cm and gives off 1 to 2 branches to the serratus before it enters the latissimus dorsi muscle on its deep surface. The serratus branch can be kept to include the serratus as part of a chimeric flap. The artery divides in the substance of the muscle into vertical and transverse branches and can facilitate a split flap.

The thoracodorsal artery courses along the posterior aspect of the axilla for 8 to 14 cm and gives off 1 to 2 branches to the serratus before it enters the latissimus dorsi muscle on its deep surface. The serratus branch can be kept to include the serratus as part of a chimeric flap. The artery divides in the substance of the muscle into vertical and transverse branches and can facilitate a split flap. Flap Design

Flap Design

The flap design can cover ipsilateral abdominal defects. If raised as an “extended” variant, it can cross the midline by incorporating the rim of supragluteal fascia.

The flap design can cover ipsilateral abdominal defects. If raised as an “extended” variant, it can cross the midline by incorporating the rim of supragluteal fascia. If based at the muscle insertion, the pivot point is at the level of the midposterior axillary line.

If based at the muscle insertion, the pivot point is at the level of the midposterior axillary line. If the insertion is incised, the island flap pivot point is 1.5 to 2 cm inferior to the pectoral humeral junction.

If the insertion is incised, the island flap pivot point is 1.5 to 2 cm inferior to the pectoral humeral junction. Marking and Dissection

Marking and Dissection

The outline of the anterior and superior edges of the muscle is made. This can be facilitated by having the patient contract the latissimus.

The outline of the anterior and superior edges of the muscle is made. This can be facilitated by having the patient contract the latissimus. If a muscle only flap needed, the incision is marked extending from the posterior axillary fold, then inferiorly and posteriorly over the anterior boarder of the latissimus muscle as dictated by the length of the muscle.

If a muscle only flap needed, the incision is marked extending from the posterior axillary fold, then inferiorly and posteriorly over the anterior boarder of the latissimus muscle as dictated by the length of the muscle. The upper two thirds of the latissimus dorsi muscle contain a higher density of myocutaneous perforators

The upper two thirds of the latissimus dorsi muscle contain a higher density of myocutaneous perforators To determine location of the skin island, the distance from the surgical defect to the pectoral-humeral junction is measured.

To determine location of the skin island, the distance from the surgical defect to the pectoral-humeral junction is measured. A line is then drawn from the anterior border of the latissimus dorsi to its origin along the posterior iliac crest, and the prior distance is transferred to this line.

A line is then drawn from the anterior border of the latissimus dorsi to its origin along the posterior iliac crest, and the prior distance is transferred to this line. The patient is placed in a lateral decubitus position on a beanbag, with an axillary roll. The ipsilateral arm is prepped completely and left in the operative field abducted and resting on a Mayo stand, placed anterosuperiorly to the patient.

The patient is placed in a lateral decubitus position on a beanbag, with an axillary roll. The ipsilateral arm is prepped completely and left in the operative field abducted and resting on a Mayo stand, placed anterosuperiorly to the patient. After incision, anterior and posterior flaps are raised superficial to the muscle to expose the latissimus. The flaps are elevated enough to gain adequate exposure for the required muscular harvest.

After incision, anterior and posterior flaps are raised superficial to the muscle to expose the latissimus. The flaps are elevated enough to gain adequate exposure for the required muscular harvest. The superior edge of the latissimus is identified at the inferior angle of the scapula and is then elevated. The serratus muscle can be identified, and dissection deep to it should be avoided. This areolar plane is easy to dissect, and some perforators are encountered and ligated.

The superior edge of the latissimus is identified at the inferior angle of the scapula and is then elevated. The serratus muscle can be identified, and dissection deep to it should be avoided. This areolar plane is easy to dissect, and some perforators are encountered and ligated. The dissection proceeds inferiorly, freeing the medial muscle origin. At the inferior/terminal portion of the muscle, there is not a clear plane, and the muscle must be divided with electrocautery.

The dissection proceeds inferiorly, freeing the medial muscle origin. At the inferior/terminal portion of the muscle, there is not a clear plane, and the muscle must be divided with electrocautery. The pedicle can be approached directly by dissecting the latissimus from the axilla, or it can be found by following the undersurface of the muscle in a distal to proximal approach.

The pedicle can be approached directly by dissecting the latissimus from the axilla, or it can be found by following the undersurface of the muscle in a distal to proximal approach. As the axilla is neared, the branch to serratus is ligated and the circumflex scapular branch can be as well if more length is needed.

As the axilla is neared, the branch to serratus is ligated and the circumflex scapular branch can be as well if more length is needed. The thoracodorsal nerve is divided, and the artery and vein can be ligated and divided when the recipient area is ready if a free flap is being used.

The thoracodorsal nerve is divided, and the artery and vein can be ligated and divided when the recipient area is ready if a free flap is being used. Closure is in layers and over drains. Mattressing sutures can be used to coapt the potential space in addition to drains.

Closure is in layers and over drains. Mattressing sutures can be used to coapt the potential space in addition to drains.3 Rectus Femoris

Anatomy

Anatomy

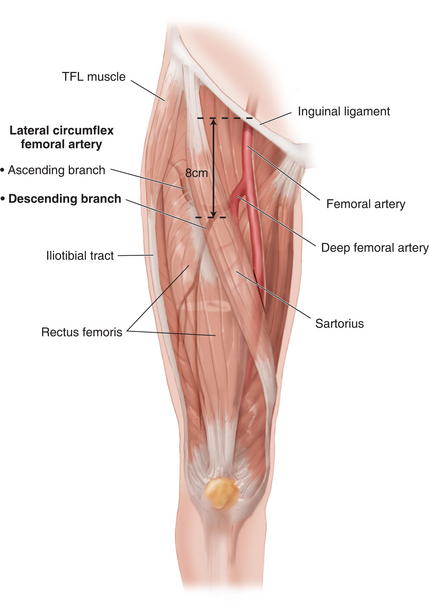

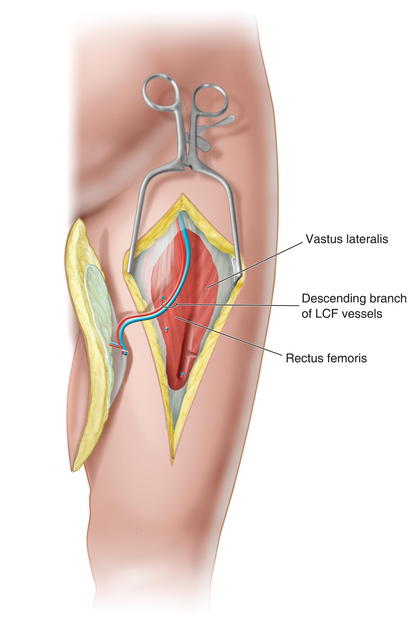

Blood supply: The descending branch of the lateral circumflex artery (1.5 to 2 mm diameter) (Fig. 15-7) from the profunda femoris is located 8 cm below the inguinal ligament and enters the muscle on its deep surface. It also supplies the tissue of the anterolateral thigh flap.

Blood supply: The descending branch of the lateral circumflex artery (1.5 to 2 mm diameter) (Fig. 15-7) from the profunda femoris is located 8 cm below the inguinal ligament and enters the muscle on its deep surface. It also supplies the tissue of the anterolateral thigh flap. Three to four musculocutaneous perforators are at the proximal portion of the muscle, and fasciocutaneous perforators from the intermuscular septum supply the skin. There are usually two venae comitantes.

Three to four musculocutaneous perforators are at the proximal portion of the muscle, and fasciocutaneous perforators from the intermuscular septum supply the skin. There are usually two venae comitantes. Muscle: It is the most anterior muscle of the quadriceps group. One can harvest muscle flap with tendinous portions both proximally and distally.

Muscle: It is the most anterior muscle of the quadriceps group. One can harvest muscle flap with tendinous portions both proximally and distally. Its origin is the anterior inferior iliac spine and the ilium just superior to the acetabulum. It inserts at the patellar tendon along with Vastus muscles.

Its origin is the anterior inferior iliac spine and the ilium just superior to the acetabulum. It inserts at the patellar tendon along with Vastus muscles. Nerve: Motor innervation is supplied by a branch of the femoral nerve, which enters the muscle at the same point as the artery. It can be >20 cm long.

Nerve: Motor innervation is supplied by a branch of the femoral nerve, which enters the muscle at the same point as the artery. It can be >20 cm long. Flap Design

Flap Design

Marking and Dissection

Marking and Dissection

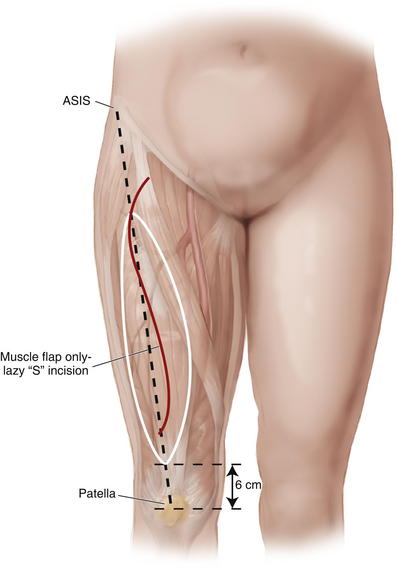

The muscle falls on a line drawn from the ASIS to the middle aspect of the patella and terminates approximately 6 cm superior to the patella (Fig. 15-8).

The muscle falls on a line drawn from the ASIS to the middle aspect of the patella and terminates approximately 6 cm superior to the patella (Fig. 15-8). If muscle only, the incision is made in a lazy “S” or a longitudinal fashion down to muscular fascia.

If muscle only, the incision is made in a lazy “S” or a longitudinal fashion down to muscular fascia. The sartorius is retracted medially and away from the leg to expose the areolar plane underneath and to identify the lateral femoral circumflex vessels. The femoral nerve and branches are also identified at this level.

The sartorius is retracted medially and away from the leg to expose the areolar plane underneath and to identify the lateral femoral circumflex vessels. The femoral nerve and branches are also identified at this level. If a skin paddle is to be used, the skin edges of the myocutaneous flap are sutured to the fascia to prevent shearing during harvest. Cutaneous perforators can be determined with the pencil Doppler.

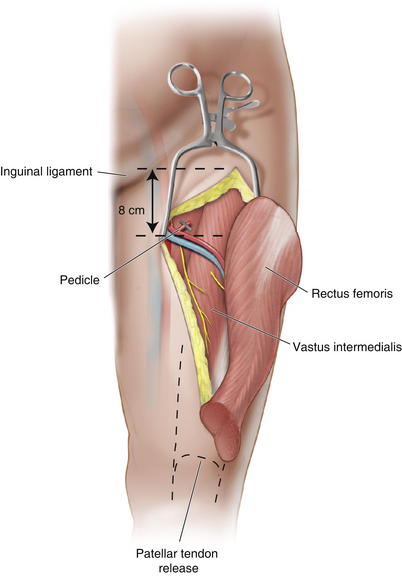

If a skin paddle is to be used, the skin edges of the myocutaneous flap are sutured to the fascia to prevent shearing during harvest. Cutaneous perforators can be determined with the pencil Doppler. The pedicle can be located by measuring 8 cm from the inguinal ligament or just proximal to the junction of the proximal and middle thirds of the muscle (Fig. 15-9).

The pedicle can be located by measuring 8 cm from the inguinal ligament or just proximal to the junction of the proximal and middle thirds of the muscle (Fig. 15-9). Ensure that the proper muscle is releasd from the other muscles conjoining at the patellar tendon, usually 6 cm proximal to the patella.

Ensure that the proper muscle is releasd from the other muscles conjoining at the patellar tendon, usually 6 cm proximal to the patella. Once the pedicle is identified on the deep surface, the muscle can then be divided proximal to the pedicle.

Once the pedicle is identified on the deep surface, the muscle can then be divided proximal to the pedicle. The remaining musculotendinuous junctions are medialized with larger figure-of-eight sutures. Suture vastus medialis and vastus lateralis to the cut rectus femoris tendon. Redirecting the remaining muscles will replace some of the lost force of the rectus femoris.

The remaining musculotendinuous junctions are medialized with larger figure-of-eight sutures. Suture vastus medialis and vastus lateralis to the cut rectus femoris tendon. Redirecting the remaining muscles will replace some of the lost force of the rectus femoris.3 Fasciocutaneous Flaps (Fig. 15-10, see Table 15-1)

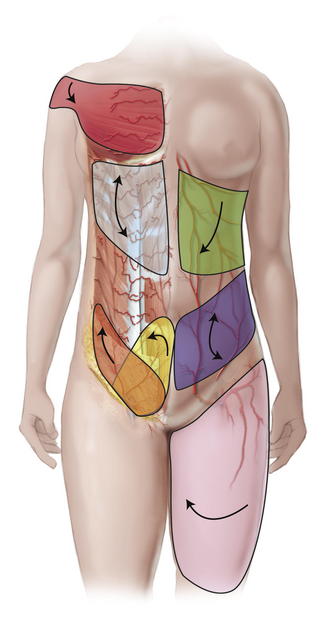

Many flaps can be created in the trunk and torso. As depicted in Figure 15-10, on the right side of the torso are axially based flaps, including the deltopectoral, thoracoepigastric, groin, and hypogastric flaps. On the left side of the torso are depictions of bipedicled and laterally based cutaneous flaps.

Many flaps can be created in the trunk and torso. As depicted in Figure 15-10, on the right side of the torso are axially based flaps, including the deltopectoral, thoracoepigastric, groin, and hypogastric flaps. On the left side of the torso are depictions of bipedicled and laterally based cutaneous flaps.1 Groin flap

Anatomy

Anatomy

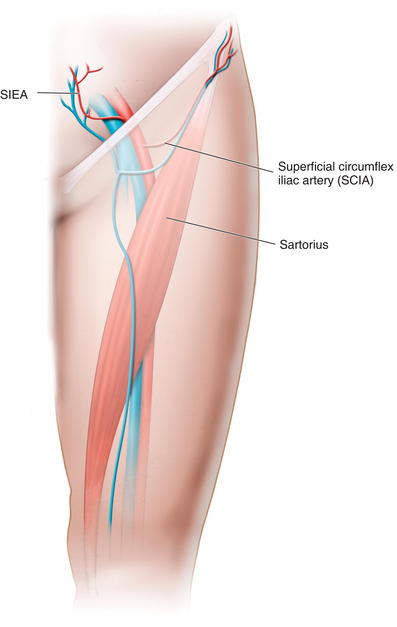

Blood is supplied by the superficial circumflex iliac artery (SCIA) from the external iliac/superficial femoral artery at the level of the inguinal ligament (Fig. 15-11). The artery may arise directly from the femoral vessel or from the trunk of a parent vessel supplying the SCIA and the deep circumflex iliac artery (DCIA). The artery also can arise from a common trunk that gives off the superficial inferior epigastric artery (SIEA).

Blood is supplied by the superficial circumflex iliac artery (SCIA) from the external iliac/superficial femoral artery at the level of the inguinal ligament (Fig. 15-11). The artery may arise directly from the femoral vessel or from the trunk of a parent vessel supplying the SCIA and the deep circumflex iliac artery (DCIA). The artery also can arise from a common trunk that gives off the superficial inferior epigastric artery (SIEA). The SCIA, which is 1 to 2 mm in diameter, pierces the fascia just lateral to the fossa ovalis at or close to the lateral border of the sartorius muscle and runs in the subcutaneous plane cranially and laterally 2 to 3 cm below the inguinal ligament. This course is maintained to the level of the ASIS and has many connections with branches of the superficial epigastric artery (SEA), DCIA, and lateral femoral circumflex artery.

The SCIA, which is 1 to 2 mm in diameter, pierces the fascia just lateral to the fossa ovalis at or close to the lateral border of the sartorius muscle and runs in the subcutaneous plane cranially and laterally 2 to 3 cm below the inguinal ligament. This course is maintained to the level of the ASIS and has many connections with branches of the superficial epigastric artery (SEA), DCIA, and lateral femoral circumflex artery. The superficial epigastric artery (SEA) runs parallel to the SCIA and may be dominant. If this is the only vessel delineated by Doppler, design the flap to incorporate this vessel.

The superficial epigastric artery (SEA) runs parallel to the SCIA and may be dominant. If this is the only vessel delineated by Doppler, design the flap to incorporate this vessel. Flap Design

Flap Design

Doppler is used to localize the arterial pedicle, usually approximately a fingerbreadth below the inguinal ligament. If not present, seek the SEA by passing the Doppler probe superior to the inguinal ligament.

Doppler is used to localize the arterial pedicle, usually approximately a fingerbreadth below the inguinal ligament. If not present, seek the SEA by passing the Doppler probe superior to the inguinal ligament. Marking and Dissection

Marking and Dissection

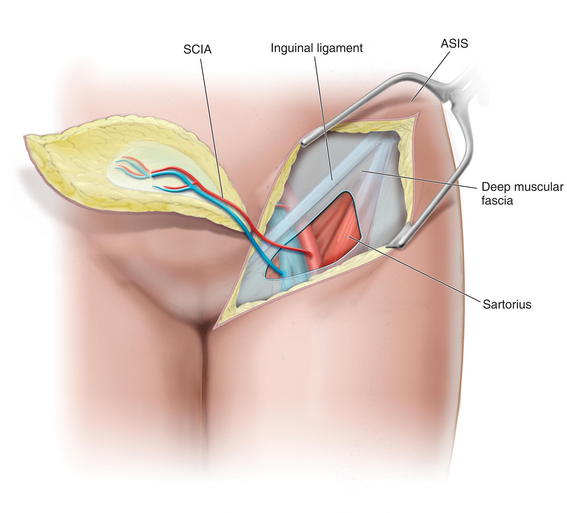

The incision is carried down to the deep fascia and the dissection begun over the deep fascia, identifying and ligating perforating vessels as one proceeds medially.

The incision is carried down to the deep fascia and the dissection begun over the deep fascia, identifying and ligating perforating vessels as one proceeds medially. At the level of the ASIS, the interval between the tensor fascia lata and the sartorius muscle is identified.

At the level of the ASIS, the interval between the tensor fascia lata and the sartorius muscle is identified. In addition, the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) of the thigh is identified as it exits the deep fascia to enter the subcutaneous tissue in its inferior course. The LCFN may need to be transected.

In addition, the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) of the thigh is identified as it exits the deep fascia to enter the subcutaneous tissue in its inferior course. The LCFN may need to be transected. At the lateral aspect of the sartorius, the muscular fascia is incised along the lateral aspect, and the flap elevation plane is now conducted deep to the muscular fascia.

At the lateral aspect of the sartorius, the muscular fascia is incised along the lateral aspect, and the flap elevation plane is now conducted deep to the muscular fascia. Proceeding medially, the superficial circumflex iliac vessels become visible in the plane above the sartorius heading into the muscular fascia.

Proceeding medially, the superficial circumflex iliac vessels become visible in the plane above the sartorius heading into the muscular fascia.2 Extended Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator Flap

Anatomy

Anatomy

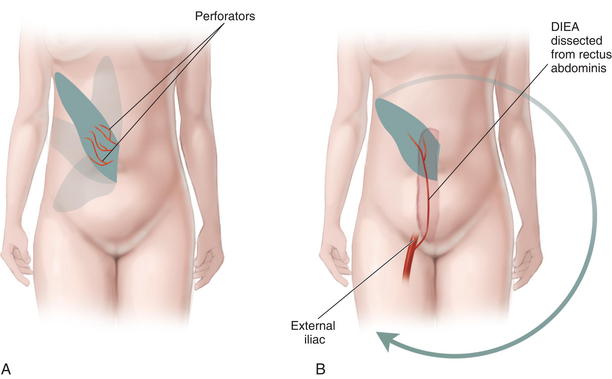

The course and connections of the deep inferior epigastric artery (DIEA) have been previously covered.

The course and connections of the deep inferior epigastric artery (DIEA) have been previously covered. If the DIEA is dissected free from the rectus abdominis muscle, a pedicle of 10 to 15 cm is possible. The pedicle can be dissected to the takeoff at the external iliac artery (Fig. 15-13).

If the DIEA is dissected free from the rectus abdominis muscle, a pedicle of 10 to 15 cm is possible. The pedicle can be dissected to the takeoff at the external iliac artery (Fig. 15-13). Flap Design

Flap Design

Markings and Dissection

Markings and Dissection

The markings are determined by the defect, with the length of the pedicle obtainable; many variations of shape and size are possible, as long as perforators are included.

The markings are determined by the defect, with the length of the pedicle obtainable; many variations of shape and size are possible, as long as perforators are included. Incision and dissection in the areolar layer on the deep surface of the subcutaneous fat begins at the distal end of the flap.

Incision and dissection in the areolar layer on the deep surface of the subcutaneous fat begins at the distal end of the flap. The sheath and muscle at the superior border are divided and the connections to the superior epigastric system are ligated.

The sheath and muscle at the superior border are divided and the connections to the superior epigastric system are ligated.3 Thoracoepigastric Flap

Anatomy

Anatomy

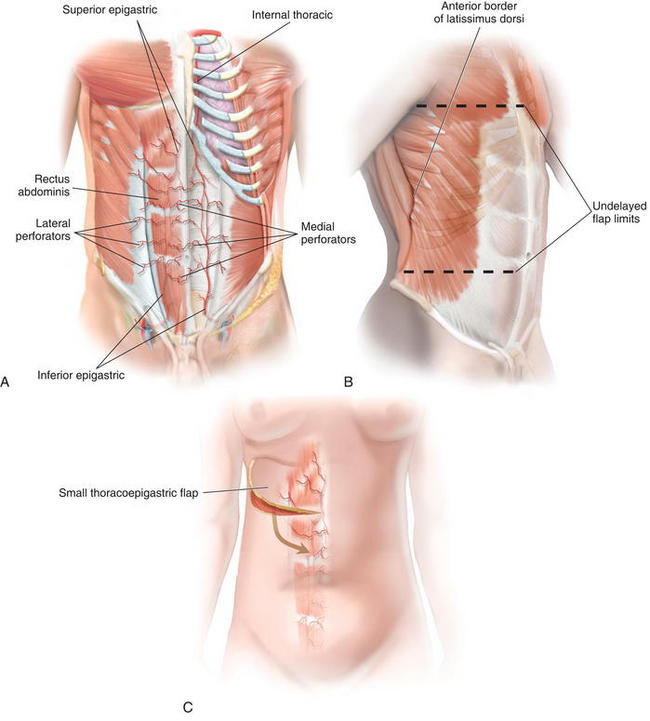

The DIEA supplies the majority of the major perforating vessels leaving the rectus abdominis muscle and running laterally to the area of the latissimus in a suprafascial plane.

The DIEA supplies the majority of the major perforating vessels leaving the rectus abdominis muscle and running laterally to the area of the latissimus in a suprafascial plane. The superior epigastric artery is smaller than the DIEA, but it supplies the upper abdominal and thoracic flaps (Fig. 15-14, A).

The superior epigastric artery is smaller than the DIEA, but it supplies the upper abdominal and thoracic flaps (Fig. 15-14, A). Flap Design

Flap Design

The flap includes skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscular fascia of the lateral thoracic and upper abdomen.

The flap includes skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscular fascia of the lateral thoracic and upper abdomen. The lateral border is the posterior axillary line or anterior edge of the latissimus dorsi muscle. A delayed flap may extend to 5 cm within the dorsal midline.

The lateral border is the posterior axillary line or anterior edge of the latissimus dorsi muscle. A delayed flap may extend to 5 cm within the dorsal midline. Marking and Dissection: (Fig. 15-14 C)

Marking and Dissection: (Fig. 15-14 C)

At the lateral aspect, the muscular intercostal perforators (usually over the serratus anterior) are divided.

At the lateral aspect, the muscular intercostal perforators (usually over the serratus anterior) are divided. The elevation from axillary line to the lateral border of the rectus is in a subfascial plane to protect the perforators.

The elevation from axillary line to the lateral border of the rectus is in a subfascial plane to protect the perforators.4 Anterolateral Thigh

Anatomy

Anatomy

The artery’s anatomy is variable with size ranging from 1 to 3 mm in diameter. The pedicle can be as long as 7 or 8 cm. It is supplied by the descending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery from the profunda femoris. The descending branch travels deep within the space between the rectus femoris muscle and the vastus lateralis muscle.

The artery’s anatomy is variable with size ranging from 1 to 3 mm in diameter. The pedicle can be as long as 7 or 8 cm. It is supplied by the descending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery from the profunda femoris. The descending branch travels deep within the space between the rectus femoris muscle and the vastus lateralis muscle. Flap Design

Flap Design

Marking and Dissection

Marking and Dissection

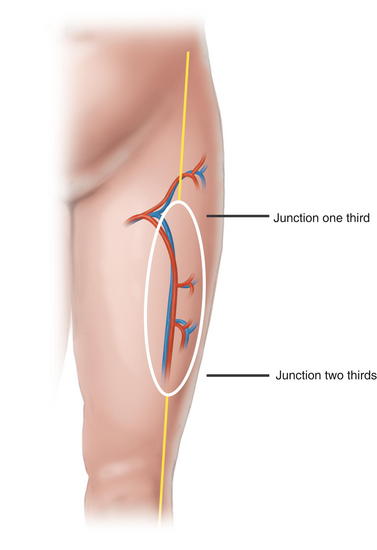

The axis of the septum between the rectus femoris and the vastus lateralis is marked by a line connecting the ASIS and the lateral patella (Fig. 15-15).

The axis of the septum between the rectus femoris and the vastus lateralis is marked by a line connecting the ASIS and the lateral patella (Fig. 15-15). This line is divided into thirds. The junction of the proximal and middle third is often the site of a perforator that pierces the TFL. It is incorporated for the rare circumstance when the distal perforators are of poor quality or injured during dissection.

This line is divided into thirds. The junction of the proximal and middle third is often the site of a perforator that pierces the TFL. It is incorporated for the rare circumstance when the distal perforators are of poor quality or injured during dissection. The junction of the middle and distal third is marked and is also incorporated into the flap (Fig. 15-16).

The junction of the middle and distal third is marked and is also incorporated into the flap (Fig. 15-16). The anterior flap is elevated first, noting any vessels perforating the rectus femoris. Vessels near the septum are preserved until the posterior flap is elevated.

The anterior flap is elevated first, noting any vessels perforating the rectus femoris. Vessels near the septum are preserved until the posterior flap is elevated. Two perforators are found and preserved. The superior perforators may arise from the rectus femoris muscle. The inferior perforators may arise either via the septum or through the medial aspect of the vastus lateralis muscle.

Two perforators are found and preserved. The superior perforators may arise from the rectus femoris muscle. The inferior perforators may arise either via the septum or through the medial aspect of the vastus lateralis muscle. The posterior flap is elevated toward the septum only after localization of a substantial perforator. If there is no usable perforator or if it is damaged during dissection, the flap is sutured back down to the donor bed.

The posterior flap is elevated toward the septum only after localization of a substantial perforator. If there is no usable perforator or if it is damaged during dissection, the flap is sutured back down to the donor bed. The lower perforator can be seen to travel through the vastus and should be dissected toward the descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery (LCFA).

The lower perforator can be seen to travel through the vastus and should be dissected toward the descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery (LCFA). The septum is identified and any septal perforators are noted. If an adequate perforator is noted, then the flap can be based upon it. Anterior elevation can continue until the septum is isolated both medially and laterally.

The septum is identified and any septal perforators are noted. If an adequate perforator is noted, then the flap can be based upon it. Anterior elevation can continue until the septum is isolated both medially and laterally. If the blood supply is entirely septal, the descending branch of the LCFA is found at the base of the septum between the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis and dissected proximally (Fig. 15-17).

If the blood supply is entirely septal, the descending branch of the LCFA is found at the base of the septum between the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis and dissected proximally (Fig. 15-17).4 Postoperative Care

Patients are allowed to ambulate at differing times, depending on the type of flap used. Free tissue transfer may preclude earlier ambulation to protect the anastomosis.

Patients are allowed to ambulate at differing times, depending on the type of flap used. Free tissue transfer may preclude earlier ambulation to protect the anastomosis. Support by an abdominal binder may be used if applied properly. A binder that is too tight may cause perfusion problems.

Support by an abdominal binder may be used if applied properly. A binder that is too tight may cause perfusion problems. Diets are advanced as tolerated, based on the amount of intestinal manipulation required during opening of the hernia and lysis of adhesions.

Diets are advanced as tolerated, based on the amount of intestinal manipulation required during opening of the hernia and lysis of adhesions.5 Pearls/Pitfalls

As previously stated, not all the described pedicled flaps are good options for free tissue transfer. There are limitations in vessel match, length of pedicle, size and type of tissue to be transferred.

As previously stated, not all the described pedicled flaps are good options for free tissue transfer. There are limitations in vessel match, length of pedicle, size and type of tissue to be transferred. For perforator based flaps, such as the ALT flap, the size and location of the perforator determines whether an additional vessel is needed.

For perforator based flaps, such as the ALT flap, the size and location of the perforator determines whether an additional vessel is needed.Gottlieb J.R., Engrav L.H., Walkinshaw M.D., Eddy A.C., Herman C.M. Upper abdominal wall defects: immediate or staged reconstruction? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86(2):281-286.

Mansberger A.R.Jr., Kang J.S., Beebe H.G., Le Flore I. Repair of massive acute abdominal wall defects. J Trauma. 1973;13(9):766-774.

Mathes S.J., Steinwald P.M., Foster R.D., Hoffman W.Y., Anthony J.P. Complex abdominal wall reconstruction: a comparison of flap and mesh closure. Ann Surg. 2000;232(4):586-596.

Rohrich RJ, Lowe JB, Hackney FL, Bowman JL, Hobar PC: An algorithm for abdominal wall reconstruction. Plast Recon Surg 105(1): 202–216.

Steinwald P.M., Mathes S.J. Management of the complex abdominal wall wound. Adv Surg. 2001;35:77-108.

Strauch B., Vasconez L.O., Hall-Findlay E.J., editors. Grabb’s Encyclopedia of Flaps, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lippincott- Raven, 1998.

Yeh K., Saltz R., Howdieshell T. Abdominal wall reconstruction after temporary abdominal wall closure in trauma patients. Southern Medical Journal. 1996;89(5):497-502.