CHAPTER 29 Rotation Mastopexy

Summary

The rotation mastopexy is a technique based on an anatomical approach.1 The lower half of the breast gland, carrying the nipple–areola complex is raised as a large flap based on a superomedial vascular supply. This is rotated in a craniolateral direction through 90° placing lateral glandular tissue into a pocket underneath the upper pole, so augmenting the upper pole with autogenous tissue, which is well vascularized. Excess skin is excised without tension and closed in a vertical fashion.

Key Points

Patient Selection

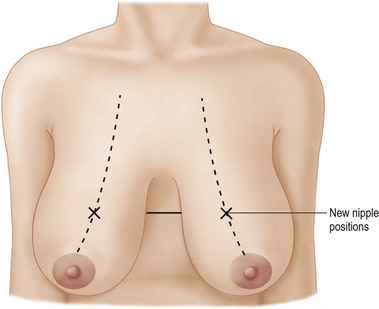

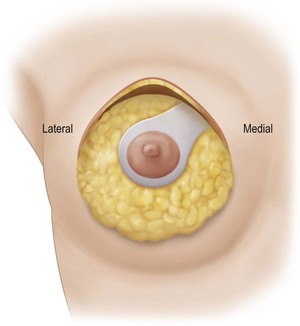

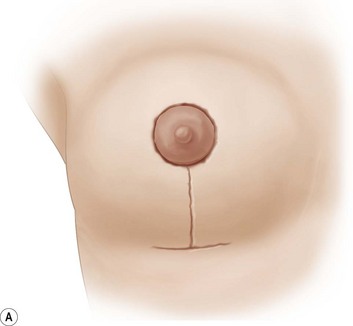

Using Regnault’s2 classification this technique is suitable for patients with Grade 1, Grade 2, and Grade 3 ptosis. After breastfeeding and with aging, the breast tissue drops to a varying degree with associated skin and ligamentous stretch. The breast also flattens and widens with some bulk of the breast tissue sitting laterally. The aim of the mastopexy is to restore tissue to the upper pole and create a breast mound with a round shape and projection (Figs 29.1–29.3). This should be done discarding a minimal amount of tissue in order to retain as much volume as possible.

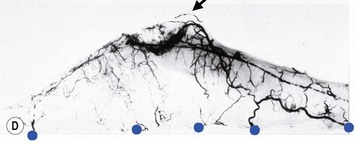

Fig. 29.1 Rotation mastopexy.

With permission from Corduff N, Taylor GI. Rotation mastopexy: an anatomical approach. Aesth Plast Surg 2009;33:377, Springer.

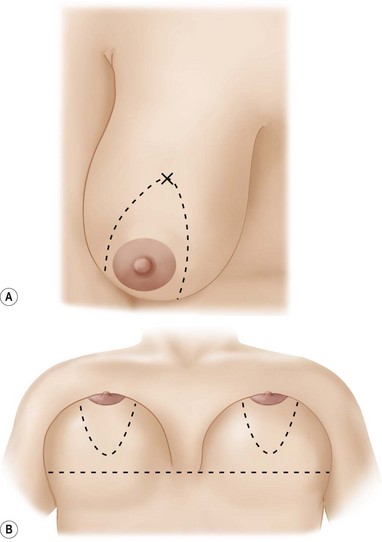

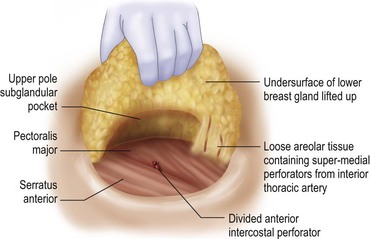

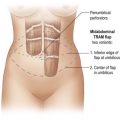

Fig. 29.2 Rotation mastopexy.

With permission from Corduff N, Taylor GI. Rotation mastopexy: an anatomical approach. Aesth Plast Surg 2009;33:377, Springer.

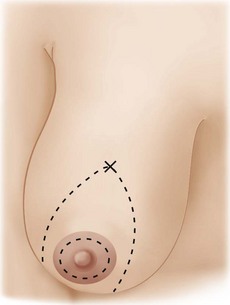

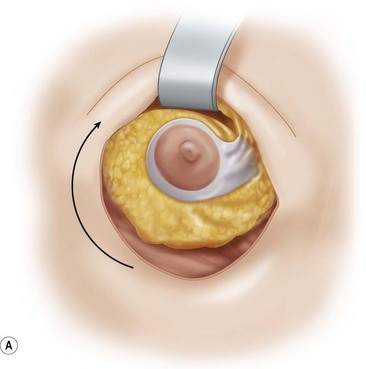

Fig. 29.3 Rotation mastopexy.

With permission from Corduff N, Taylor GI. Rotation mastopexy: an anatomical approach. Aesth Plast Surg 2009;33:377, Springer.

The technique is also suited to those patients who have breast ptosis in association with breast implants in situ (Fig. 29.4). In a patient who has had breast implants in situ for many years it is not unusual to find the tissue in the central and upper poles to be thinned out, with the bulk of the breast tissue to be lying below the implant. Many of these patients have put on some weight and there is sufficient volume to recreate an adequate breast mound from the available tissue without having to use new implants.

Indications

In restoration of the breast shape to a more youthful appearance, volume needs to be restored to the upper pole. The skin envelope is reduced and the nipple restored to an aesthetically correct position on the new breast mound. Commonly, adaptation of breast reduction techniques3 are used in a mastopexy, resecting mainly skin and a smaller amount of breast tissue. Following surgery the tightened skin envelope relaxes over time and the upper pole fullness is often lost leaving a less than optimal result. Ideally a technique should be used that reshapes the breast without relying on the skin envelope to hold it. Techniques have been described using small glandular flaps transposed to increase projection,4–9 but these do not adequately fill out the upper pole. Alternatively combining the reduction approach with an implant to fill out the upper pole10–14 is well described but associated with a significant complication rate.13,14

In those patients for explantation of breast prostheses, mastopexy at the time of implant removal is often a good option in that it will avoid a secondary deformity. Otherwise there is a risk that the pocket will contract down in an irregular fashion and lead to a subsequent deformity that can be hard to fix, especially in a patient whose tissues are not as elastic as they once were.15

It has been suggested that leaving the capsule behind can lead to increased seroma formation.16 This has not been the experience of the author. The approach to explantation is to leave the capsule behind if it is not heavily calcified and there is no free silicone present around the implant. Otherwise as much of the capsule that can be safely removed is excised. (Often some of the posterior capsule in the subpectoral pocket is left where it is closely adherent to the ribs.)

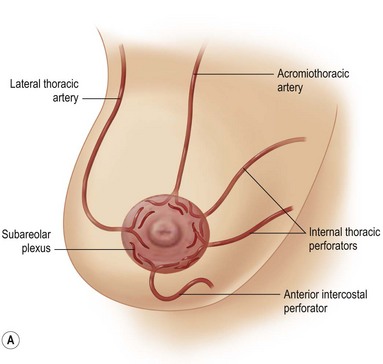

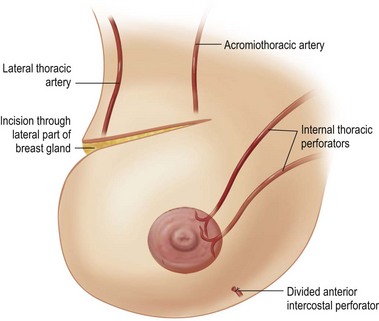

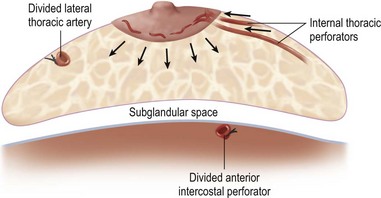

Anatomy

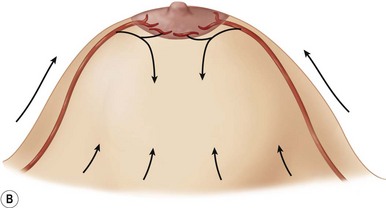

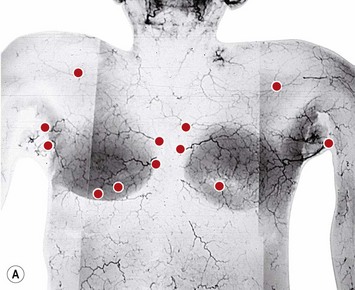

The blood supply to the breast has been described before.1 The dominant supply to the integument of the anterior chest is from: the internal thoracic artery medially, especially from the second and third intercostal spaces; the lateral thoracic artery laterally; the anterior intercostal arteries inferiorly, especially from the fourth and fifth intercostal spaces in the region of the pectoralis major origin inferiorly and; from the acromiothoracic perforator and supraclavicular vessels superiorly. These vessels anastomose in the vicinity of the nipple–areola complex (Figs 29.5 and 29.6).

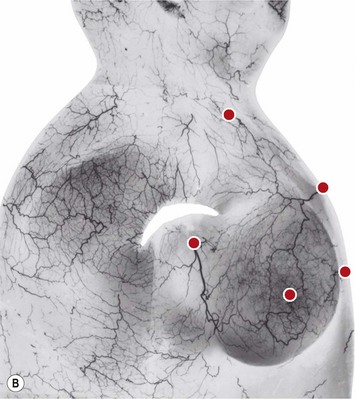

The breast in the female is a modified sweat gland. Like a tissue expander, it has enlarged from the skin at the nipple into the subcutaneous tissues, elongating these vessels from their fixed skin origins and compressing them towards the periphery of the gland (Figs 29.5B and 29.6) to form a vascular hood. Within the boundary of this vascular perimeter there is a relatively avascular mobile plane between the under surface of the breast and the fascia over pectoralis major. This is utilized by the surgeon when introducing a breast prosthesis, after first dividing the vascular perimeter inferiorly.

The dominant supply to the breast is by vessels which penetrate the gland from the ‘vascular hood’ following the connective tissue framework between the breast lobules. Many of these penetrating vessels arise from the sub-areolar network. This arrangement of blood supply provides the anatomical basis for: (i) entering the avascular plane between the breast and pectoralis major centrally; (ii) raising a large flap of glandular tissue based on the vessels coursing towards the subareola plexus from the internal thoracic artery via the second and third intercostal spaces (Fig. 29.7), which (iii) then supply the rest of the glandular tissue retrogradely with penetrating vessels from the subareola plexus (Fig. 29.8); and (iv) leaving the glandular tissue in the upper pole well vascularized from the acromiothoracic and supraclavicular vessels (Fig. 29.7).

Operative Technique

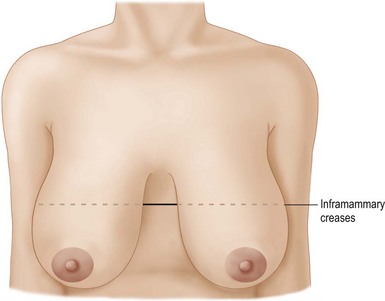

Markings

The patient is marked in the sitting position. The inframammary creases are marked (Fig. 29.9) and the new nipple position placed at the level of the inframammary crease using a tape measure placed under the breasts as a guide. The midmammary line is marked on each breast bisecting the breast mound and the new nipple position placed on this line (Fig. 29.10).

From this marking an ellipse is drawn skirting the existing areola, to a point about 2 cm above the inframammary crease along the midmammary line (Fig. 29.11). The new, reduced areola circumference is marked (Fig. 29.12).

Surgical technique

The patient is positioned on the operating table before induction of anesthesia. To enable surgery in the upright position it is necessary to safely secure the head and arms prior to induction of anesthesia. The arms are placed in stirrups with the patient sitting up. A pillow is placed under the knees. The arms are held in position with tape. The patient is then laid flat for induction of anesthesia. The head is taped in position on a head ring (Fig. 29.13).

A broad-spectrum antibiotic is administered at the induction of anesthesia.

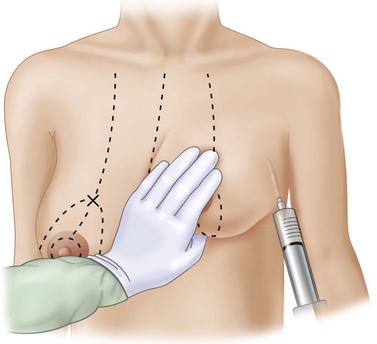

The breasts are infiltrated laterally, medially and inferiorly with 100 ml 0.2% ropivacaine (Naropin, Astra) as a field block injected in a ‘U’ at the periphery of the breast gland (Fig. 29.14).

Fig. 29.14 Local anesthetic infiltration injected subcutaneously in a ‘U’ around the periphery of the breast.

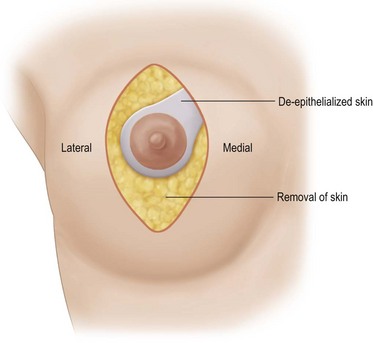

A desired areola is marked within the ellipse. From this new areola a wide pedicle of approximately 4 cm is marked extending superomedially to the medial edge of the drawn ellipse to encompass the superomedial intercostal vascular axis (Fig. 29.15). The areola skin outside the desired areola circumference is de-epithelialized to protect the underlying superficial venous plexus. The area of the pedicle is de-epithelialized and then the rest of the skin within the ellipse is excised (Fig. 29.15).

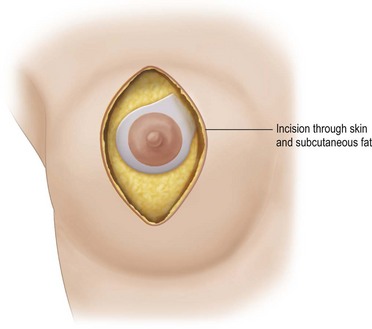

The elliptical skin incision is deepened through the subcutaneous fat down to the breast gland (Fig. 29.16). Peripheral to the ellipse a plane is developed between the gland and the subcutaneous fat. Inferiorly this is taken down to the inframammary fold, medially, to over approximately the fifth intercostal space and laterally to approximately the fifth space at the base of the breast (Fig. 29.17). The dissection can extend quite far laterally, even to the midaxillary line to reach the perimeter of the attachment of the breast gland at the pre-pectoral fascia.

Fig. 29.16 The elliptical skin incision is deepened through the subcutaneous fat down to the breast gland.

The freed lower gland is then lifted off the prepectoral fascia. It is at this stage that any implants can be removed (see below.) In continuity a subglandular pocket is created behind the upper pole by dissecting in the plane of the loose areolar tissue nearly to the clavicle in the central breast area. The superomedial perforators can be seen appearing peripherally in the loose areolar layer underneath the breast gland (Fig. 29.18).

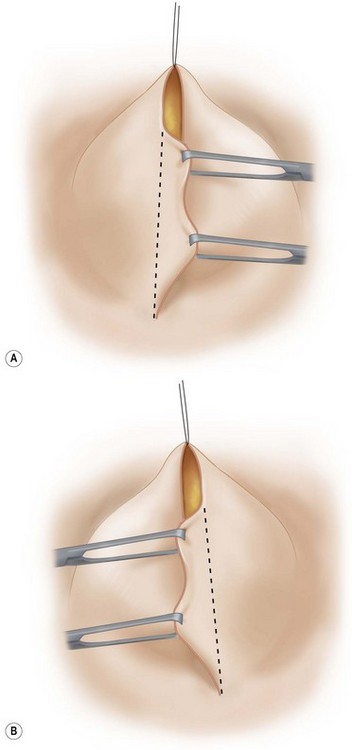

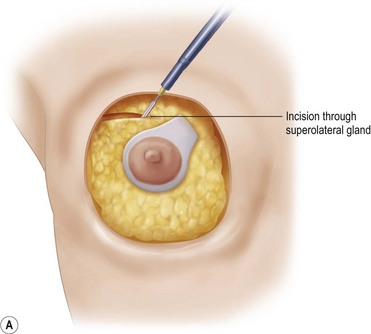

An incision is made superolaterally through the full thickness of the upper gland at the level of the apex of the ellipse, lifting just enough subcutaneous tissue to allow the incision to cross to the upper apex of the skin ellipse (Fig. 29.19) The lower gland is left in continuity with the upper pole via its broad superomedial attachment.

Fig. 29.19 A, B The superolateral gland is divided, leaving a broad superomedial attachment.

B With permission from Corduff N, Taylor GI. Rotation mastopexy: an anatomical approach. Aesth Plast Surg 2009;33;377, Springer.

The mobilized lower gland is rotated craniolaterally into the upper pocket (Fig. 29.20). It is then stitched with a couple of supporting 0 Prolene sutures (Johnson and Johnson, Somerville, NJ) to the prepectoral fascia, high in the upper pocket.

The patient is brought to a sitting position. The lateral skin flap is grasped with a pair of tissue forceps under a little tension. A line is drawn between the two apices of the ellipse and then excess skin and subcutaneous fat resected. Care is taken not to resect too much so as to give a soft, tension free lower pole curve (Fig. 29.21A). The procedure is repeated with the medial skin flap (Fig. 29.21B).

The skin is loosely closed in a vertical fashion with some deep interrupted 3-0 Monocryl sutures. A small transverse extension is made in the inframammary crease to excise the ‘dog ear’ at the lower end of the closure. A new position is drawn for the areola encircling the apex of the vertical closure and a circular opening made in the skin (Fig. 29.22). The areola is brought into this opening. The skin closure is completed with 3-0 Monocryl deep dermal everting sutures.

Operative Steps

Pitfalls and How to Correct

Circulatory compromise

Problems with circulation, with subsequent fat necrosis, and at the worst nipple loss, can be potentially catastrophic. These patients are less likely to be as forgiving as breast reduction patients as they are seeking surgery purely for cosmetic improvement as opposed to relief of physical symptoms. The author has not seen a vascular compromise with this particular procedure but has experienced it in breast reduction surgery (Fig. 29.23) and expects one day to see it in this scenario too. The nipple–areola complex color can be regarded as a barometer of circulation within the whole of the flap of which it is part. Ultimately, the skin of the areola may recover but the fat behind is unlikely to do so and fat necrosis can ensue.

Asymmetry

Postoperative asymmetry is more prevalent than with other mammaplasty operations. One reason is due to potentially more tethering of the rotated pedicle on one side than the other. One must think in a three-dimensional approach to avoid this. One must not only consider the height of the nipple on the breast mound (at the apex of the ellipse) but also the degree of freedom of the nipple to fall forward once the rotated flap is sutured into its new pocket giving central projection. Thankfully much of this asymmetry is temporary and resolves as the breast swelling settles and the breasts soften (Fig. 29.24 and see Fig. 29.2). It would be unusual to need a surgical revision for correction (certainly no more than with other breast surgeries).

1 Corduff N, Taylor GI. Subglandular breast reduction: the evolution of a minimal scar approach to breast reduction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:175.

2 Regnault P. Breast ptosis: definition and treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 1976;3:193.

3 Rohrich RJ, Gosman AA, Brown SA, Reisch J. Mastopexy preferences: a survey of board-certified plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(7):1631-1638.

4 Graf R, Biggs TM. In search of better shape in mastopexy and reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:309-317.

5 Ribeiro L. A new technique for reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;55:330.

6 Caldeira AML, Lucas A, Grigalek G. Mastopexy: the triple-flap interposition technique. Aesth Plast Surg. 1999;23(1):51-60.

7 Ritz M, Silfen RMD, Southwick G. Fascial suspension mastopexy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(1):86-94.

8 Hall-Findlay EJ. Pedicles in vertical breast reduction and mastopexy. Clin Plast Surg. 2002;29(3):379-391.

9 Foustanos A, Zavrides H. A double-flap technique: an alternative mastopexy approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(1):55-60.

10 Elliott FL. Circumareolar mastopexy with augmentation. Clin Plast Surg. 2002;29(3):337-347.

11 Gruber R, Denkler K, Hvistendahl Y. Extended crescent mastopexy with augmentation. Aesth Plast Surg. 2006;30(3):269-274.

12 Cardenas-Camarena L, Ramirez-Macias R. Augmentation/mastopexy: how to select and perform the proper technique. Aesth Plast Surg. 2006;30(1):21-33.

13 Spear SL, Boehmler JH4th, Clemens MW. Augmentation/mastopexy: a 3-year review of a single surgeon’s practice. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(7):136S-147S.

14 Stevens WG, Freeman ME, Stoker DA, Quardt SM, Cohen R, Hirsch EM. One-stage mastopexy with breast augmentation: a review of 321 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(6):1674-1679.

15 Rohrich RJ, Parker THIII. Aesthetic management of the breast after explantation: evaluation and mastopexy options. Plast Recoustr Surg. 2007;120:312-315.

16 Netscher DT. Aesthetic outcome of breast implant removal in 85 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(3):1057-1059.