CHAPTER 10 Role of Surgery in the Treatment of Varicose Veins

Basis and Aim of Surgery

In practice the aim is twofold:

The Different Surgical Procedures

Surgery without saphenous trunk preservation

Principle and Controversies

Technical Information

Conventional surgery variants

Saphenous Trunk Stripping with Preservation of Saphenofemoral Confluence, with or without Incompetent Tributary Phlebectomy and/or Incompetent Perforator Interruption

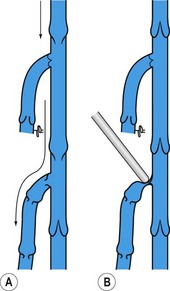

Non-flush ligation at the SFJ and/or SPJ was, until recently, described as a technical mistake responsible for in situ recurrence in all cases as reflux through the incompetent terminal valve persisted. But preoperative ultrasound investigations have proved that in GSV varices the terminal valve is competent in approximately half the patients.11,12

In this situation it looks obvious that high flush tie is not recommended as tributaries of the saphenofemoral confluence can drain in a physiologic way into the common femoral vein. Besides neovascularization, elimination of normal physiologic reflux is the main cause of recurrence after flush ligation,13 but rarely identified after confluence conservation.14

When the terminal valve is incompetent, non-flush ligation was thought to promote recurrence, as previously stated (Fig. 10.4). However, one prospective study has demonstrated that this concept is wrong. In this large series neither postoperative outcome nor clinical and diagnostic evaluation found a difference in terms of recurrence if the terminal valve was competent or not.14

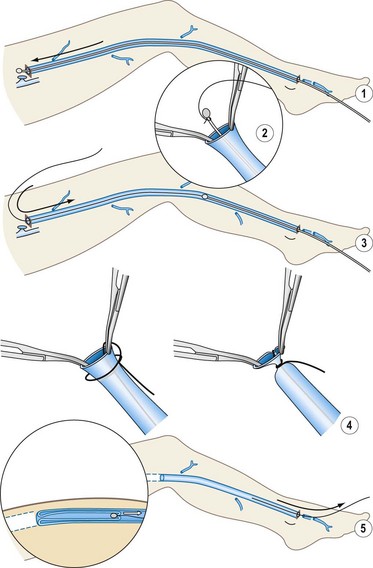

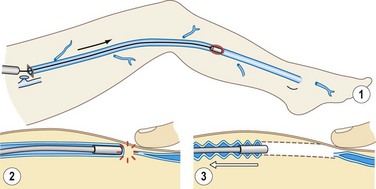

Cryostripping

The only difference with cryostripping in comparison to classical surgery is the ablation modality of the saphenous trunk. After HL, the saphenous trunk is catheterized downward with the cryoprobe until reaching the lower limit of the vein to be stripped. The generator is activated and when the vein is attached to the cryoprobe (by freezing to it) the vein is broken off easily. No distal ligation is needed and the vein attached to the probe is progressively pulled up and extracted through the groin incision (Fig. 10.5).

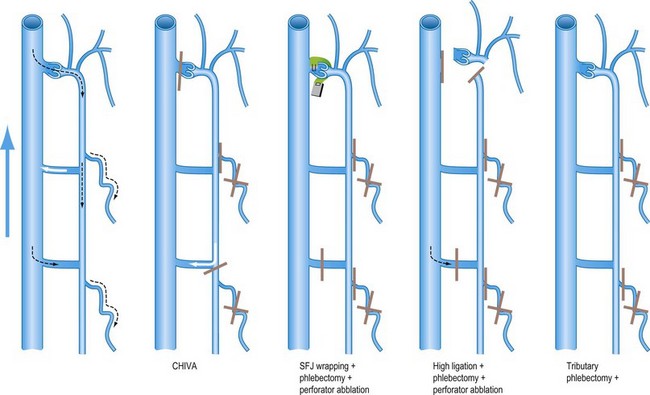

Surgery with saphenous trunk preservation

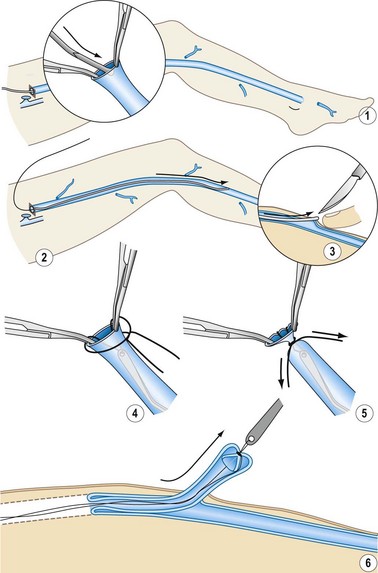

This is less invasive than other procedures, including vein stripping. The most aggressive part of vein stripping is the trunk excision. Besides, supporters claim that the preserved saphenous trunk might be used as an arterial substitute either for coronary surgery or as a bypass in femorocrural obliteration. Unfortunately there are no data on the real need for, or value of, the saphenous trunk as an arterial substitute after such surgery. Another argument in favor is the preservation of venous flow drainage, as ablation of the superficial system enhances varicose vein recurrence. The different procedures are depicted in Figure 10.6.

SFJ and/or SPJ ligation plus incompetent tributary phlebectomy with or without incompetent perforator interruption

Suppression of leak points between the DVS and the SVS combined with reservoir ablation is supposed to restore competence of the saphenous trunk.15–18 This procedure was promoted during the last two decades but is presently rarely performed, probably because the myth of compulsory HL has been discredited on account of its lack of clinical efficacy.

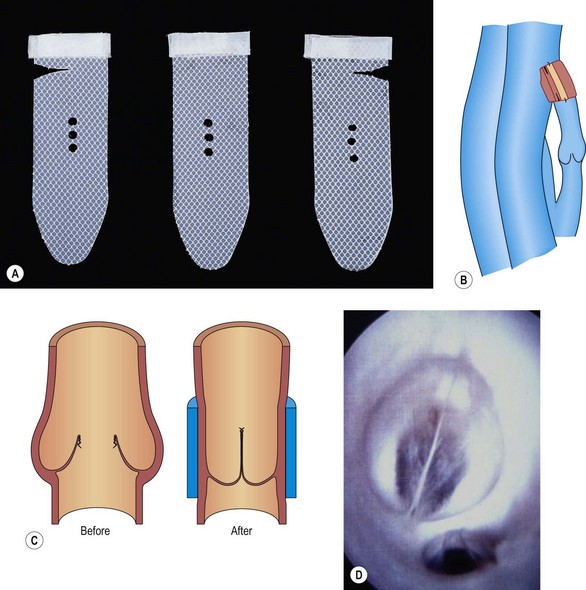

SFJ wrapping or valvuloplasty plus incompetent tributary phlebectomy with or without incompetent perforator interruption

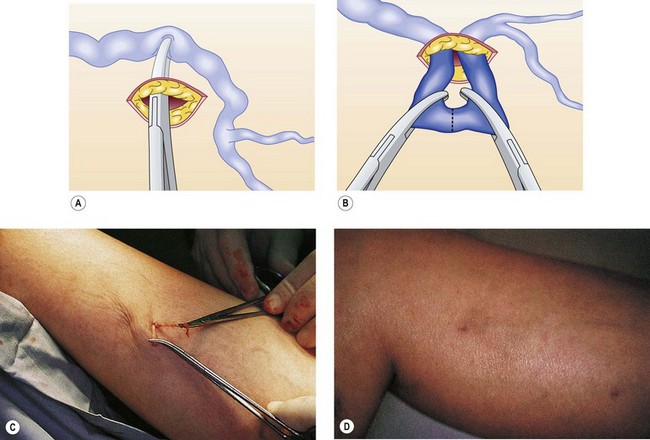

Ambulatory phlebectomy

Muller described this technique in 1956 and published it 10 years later.26 The method consists of extracting VVs in an outpatient setting under local anesthesia using small punctures and hooks, The procedure is described in detail elsewhere,27–29 but it is worth mentioning here that phlebectomy is performed by using fine-pointed blades, mini-incisions, and crochet hooks or other specialized phlebectomy hooks (Fig. 10.8).

Muller used this procedure in isolation or in combination with trunk stripping to avulse tributary varices, as reported in 1996.30

A powered phlebectomy device, the Trivex system (InaVein LLC, Lexington, Mass.), was introduced by G. Spitz in1966. Briefly, the system contains a shaver and a transilluminator coupled with an irrigator (Fig. 10.9).

Varices phlebectomy

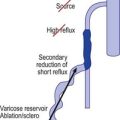

Varices phlebectomy with conservation of the refluxing saphenous trunk is named in French ‘ablation sélective des varices sous anesthésie locale’ (ASVAL; selective ablation of varices under local anesthetic).31 This process gathers and unifies techniques of phlebectomy that were previously scattered and insufficiently systematized and is based on the demonstrated fact that varicose disease most often begins at lower leg level (see above). According to ASVAL principles, the suppression of varicose reservoirs (especially extra fascial varicose clusters) can – at least to a certain extent – improve or restore to normal (centripetal) the reflux in saphenous trunks, thus preserving them.32

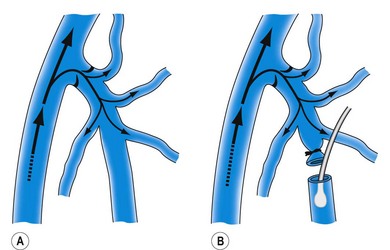

CHIVA method

CHIVA is the acronym of the French ‘Cure Conservatrice et Hémodynamique de l’Insuffisance Veineuse en Ambulatoire’.33 The pathophysiological basis of CHIVA relates to a ‘hemodynamicocentric model’ of venous insufficiency (VI).34

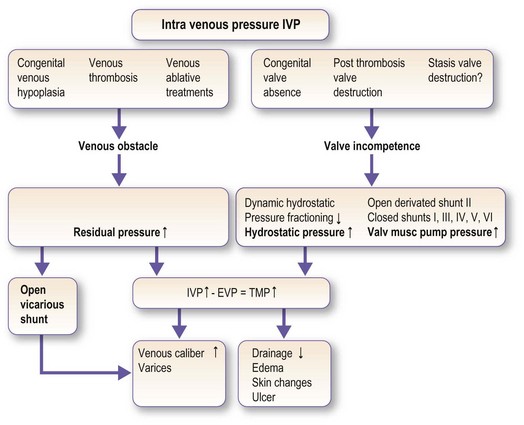

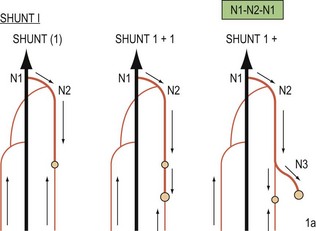

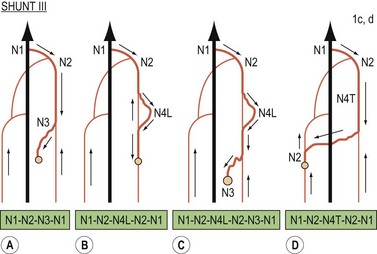

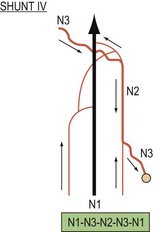

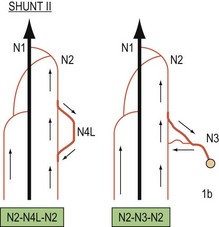

According to CHIVA all the VI symptoms are due to an obstacle to the flow and/or valvular incompetence which increases the transmural pressure (TMP). Excessive TMP dilates the veins (varices) and impairs drainage (edema, lipodermatosclerosis, and ulcer) (Fig. 10.10). The hemodynamic diagnosis consists of checking and, correcting the VI causes in order to normalize the TMP and, consequently, its clinical symptoms. According to the VI hemodynamic pattern, CHIVA involves fractioning the hydrostatic pressure, disconnecting the shunts, and preserving the draining veins in order to cure all the symptoms of VI at the same time and avoid recurrence. Open Deviated Shunts Type II (varices + segmental saphenous trunk reflux) and Closed Shunts Type III (varices + segmental saphenous trunk reflux + SFJ reflux (SFJR)) are frequent patterns of VI due to superficial valve incompetence. In these specific cases CHIVA divides the refluxing tributaries at their junction with the saphenous trunk. These divisions result in trunk reflux suppression and varices ‘remodeling’ to normal size while the drainage is preserved in order to avoid short-term side effects and long-term recurrences (in the case of Shunt III SFJR, redo due to a trunk re-entry) (Figs 10.11–10.14).

Figure 10.12 Types of ‘private circulation’ or veno-venous shunts according to CHIVA nomenclature.

(Courtesy of Dr Franceschi.)

Investigations to be Done Before VV Surgery

Systematic DUS prior to surgery for varicose veins is crucial. From a classification standpoint, DUS is used to complete CEAP sections E, A and P. In practical terms, it allows creation of a precise map that will be very useful during surgery (Fig. 10.15).

Patient’s Information

In addition, a written document is handed over to the patient (Appendix 10.1).

Anesthesia and Hospitalization

Anesthesia

Regardless of the technique used, surgery may be performed under local anesthesia (LA). Tumescent anesthesia is strongly recommended for all patients. This innovation has revolutionized surgery of varicose veins.35,36

The addition of epinephrine (adrenaline) does decrease ecchymosis, and Goldman has shown that in appropriate concentrations, epinephrine is safe when used in a tumescent anesthetic technique during ambulatory phlebectomy. It does reduce the incidence of hematoma and hyperpigmentation.37,38

Postoperative Care and Convalescence

Recovery and convalescence

Recovery depends on the surgery performed and the level of patient activity: from 2 weeks for extensive excisional surgery to a maximum of a few days for so-called conservative surgery. The norm is rising with movement on the day of the procedure, depending on the procedure performed – with mini invasive and LA procedure immobility time is shortened. Exercise time is progressively increased during recovery. In principle, surgeons should provide patients with a document showing all postoperative instructions (Appendix 10.1).

Surgical Complications39,40

Postoperative complications

Neurologic complications

Neurologic complications41–43 are more frequent after trunk stripping, are mainly associated with perioperative injury and, rarely, when elastic compression is applied to patients under general anesthesia. Lesions to the motor nerves are extremely rare but may be permanent. In contrast, lesions to superficial sensory nerves, estimated at between 10% and 40%, lead to disorders such as anesthesia, paresthesia, dysesthesia and, more rarely, neuralgia. The patient often only becomes aware of these neurological disorders a few days after the procedure and they usually disappear within a few weeks, sometimes after several months. They are rarely permanent.

Venous thromboembolic complications

Local anesthesia and early mobilization have certainly reduced the frequency of such complications. Analysis of two prospective series with systematic DUS examination showed that, after ancillary surgery, DVT and pulmonary embolism were, respectively, 0.4 to 5.3% and 0.2 to 0%,44,45 demonstrating that most of the DVTs were distal and asymptomatic. It should, however, be noted that in the first series the patients (n = 377), who were treated by HL + saphenous trunk stripping + tributary phlebectomy and/or ligation of the perforating veins, were operated on under general anesthesia followed by early mobilization and postoperative compression, but patients at risk for DVT were not systematically given preventive anticoagulation. In the second series various open surgery procedures were performed, but under LA. Although no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the two modes of anesthesia are presently available, it appears that venous thromboembolic complications are more frequent with general anesthesia.

Results from Surgery

In a comprehensive review including 118 references the authors’ conclusions were46 that surgical treatment seems to:

Surgery without preservation of the saphenous trunk

Conventional surgery

Natural Evolution of the Disease Versus Conventional Surgery

A set of 149 patients with uncomplicated but symptomatic VVs, who had chosen 6 months earlier whether or not to be treated, were assessed by a questionnaire.47 Surgery significantly reduced the total number of symptoms reported by the patients at follow-up (P < 0.02). However, none of the symptoms reported during specific activities were significantly lessened by surgery compared with no treatment.

Conservative Treatment Versus Conventional Surgery

Two RCTs have been conducted, one concerning symptomatic patients with non-complicated varicose veins, the other one in patients with venous ulcers. The outcome is displayed in Table 10.1.48–52

Table 10.1 Conservative treatment versus conventional surgery

| Type of Procedure | Article | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Uncomplicated symptomatic VVs HL+S versus conservative treatment |

Michaels JA, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing surgery with conservative treatment for uncomplicated varicose veins. Br J Surg 2006;93:175 | 246 patients Uncomplicated symptomatic VVs (C2S) Conservative treatment (lifestyle advice) versus HL+S |

| F-U 2 years After surgery Health-related QoL better Symptoms improvement (pain and edema feeling) Cosmetic improvement |

||

| Ratcliffe J et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of surgery versus conservative treatment for uncomplicated varicose veins in a randomized control trial. Br J Surg 2006;93:182 | 246 patients Uncomplicated VVs (C2S) Conservative treatment (lifestyle advice) versus HL+S |

|

| F-U 2 years After surgery Modest health benefit for relatively little NHS cost (United Kingdom) |

||

| Venous ulcer HL+S and compression versus compression |

Barwell JR, Davies CE, Deacon J Harvey K, et al. Comparison of surgery and compression with compression alone in chronic venous ulceration (ESCHAR study): randomized control trial. Lancet 2004;363:1854 | 500 extremities HL+S and compression versus compression Venous ulcer healing (C6) F-U 24 weeks No difference between the 2 groups |

| Ulcer recurrence prevention F-U 1 year Less ulcer recurrence in the surgical group. P < 0.0001 |

||

| Guest M, Smith JJ, Tripuraneni G, Howard A, Madden P, Greenhalgh RM, Davies AH. Randomized clinical trial of varicose vein surgery with compression versus compression alone for the treatment of venous ulceration. Phlebology 2003;18:130-6;363 Ulcer | 76 patients Ulcer healing F-U 26 weeksCompression (n = 39) versus HL+S and compression (n = 37). Surgery gives no additional benefit to compression therapy from the point of view of healing rate and quality of life generic questionnaire (SF 36) and disease specific questionnaire (CXVUQ) |

|

| Gohel MS, Barwell JR, Earnshaw JJ, et al. Randomized clinical trial of compression + surgery versus compression alone in chronic venous ulceration. (ESCHAR study)-haemodynamic and anatomic changes. Br J Surg 2005;92:291 | Venous ulcer Compression (n = 112) versus HL+S+ compression (n = 102) |

|

| F-U 1 year Saphenous surgery abolished deep reflux in 10 of 22 legs with segmental reflux and 3 of 17 with axial reflux. P = 0.175 A significant hemodynamic benefit was obtained despite co-existent deep reflux; residual saphenous reflux was common |

||

| Gohel MS, Barwell JR,Taylor M, et al. Long term results of compression therapy alone versus compression plus surgery in chronic venous ulceration (ESCHAR): randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2007;335:83 |

F-U, follow-up; HL, high ligation; NHS, National Health Service; QoL, quality of life; S, saphenous stripping.

Outcome of conventional surgery in observational studies

Only two prospective observational studies will be analyzed here. The patients had been treated at centers highly skilled in venous surgery, investigated in depth pre- and postoperatively by USD and there was no patient loss at 5 years follow-up.53,54

In the first one including 93 patients (113 extremities C2-6) the recurrence rate according to the REVAS (recurrent varices after surgery) definition55 was 25% (28/113), of which 72% were symptomatic (20/28). Nevertheless the clinical score was an improvement on the preoperative one (P < 0.001). The main cause of REVAS was neovascularization at the SFJ.

RCTs on Conventional Surgery Versus Other Operative Treatment

The results of these trials are shown in Table 10.256,57(HL+ conventional stripping vs HL+ cryostripping), Table 10.358–64 (HL+S vs radiofrequency ablation (RFA)), Table 10.465–68 (HL+S vs endovenous laser ablation (EVLA)), Table 10.516,17,69–71 (HL+S vs surgery preserving the GSV), and Table 10.672–74 (HL+S vs foam sclerotherapy).

Table 10.2 RCTs of HL+ conventional stripping versus HL+ cryostripping

| Type of Procedure | Article | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| HL + S (conventional) versus HL + cryostripping |

Menyhei G et al. Conventional stripping versus cryostripping: a prospective randomised trial to compare improvement in quality of life and complications. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008;35:218 | HL + S (n = 80) versus HL+ cryostripping (n = 79) |

| F-U 6 months No difference in terms of postoperative pain and outcome Less bruising with cryostripping P = 0.01 |

||

| Taco MAL et al. A randomized trial of cryo-stripping versus conventional stripping of the great saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg 2009;49:403 | HL + S (n = 245) versus HL+ cryostripping (n = 249) | |

| F-U 6 months Cryostripping has no benefits over conventional stripping. |

F-U, follow-up; HL, high ligation; S, saphenous stripping.

Table 10.3 RCTs (except Kianifard article) HL+S versus RFA

| Type of Procedure | Article | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| HL+S versus RFA |

Hinchliffe RJ, et al. A prospective randomised controlled trial of VNUS Closure versus surgery for the treatment of recurrent long saphenous varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006;31:212 | 16 patients presenting REVAS with persistent GSV trunk RF VNUS Closure bipolar catheter versus redo-groin surgery + S. |

| F-U 10 days With RF Procedure shorter P = 0.02 Less post-operative pain. P = 0.02 Less bruising P = 0.03 |

||

| Kianifard B, et al. Radiofrequency ablation (VNUS Closure) does not cause neo-vascularisation at the groin at one year: results of a case controlled study. Surgeon 2006;4:71 | 55 patients treated by VNUS closure bipolar catheter versus HL+S (control group) | |

| F-U 1 year Absence of neovascularization after RFA 11% after conventional surgery P = 0.028 |

||

| Lurie F et al. Prospective randomized study of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration (Closure procedure) versus ligation and stripping in a selected patient population (EVOLVES Study). J Vasc Surg 2003;38:207 | 86 patients VNUS Closure bipolar catheter versus HL+S |

|

| F-U 4 months With RFA Return to normal activity shorter P = 0.02 Return to work shorter P = 0.05 Better health-related QoL |

||

| Lurie F et al. Prospective randomized study of 65 endovenous radiofrequency obliteration (Closure) versus ligation and vein stripping (EVOLVeS) Two-year follow-up. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2005;29:67 | 65 patients VNUS Closure bipolar catheter versus HL+S |

|

| F-U 2 years With RFA Clinical and DUS results at least equal to those after HL+S Better health-related QoL |

||

| Rautio T, et al. Endovenous obliteration versus conventional stripping operating in the treatment of primary varicose veins: a randomized controlled trial with comparison of the costs. J Vasc Surg 2002;35:958 | VNUS Closure bipolar catheter (n = 15) versus HL+S (n = 13) | |

| F-U 2 months Less post-operative pain P = 0.017–0.036 Shorter convalescence. P < 0.001 Cost-saving for society in employed patients |

||

| Perala J et al. Radiofrequency endovenous obliteration versus stripping of the long saphenous vein in the management of primary varicose veins: 3-year outcome of a randomized study. Ann Vasc Surg 2005;19:1 | VNUS Closure bipolar catheter (n = 15) versus HL+S (n = 13) F-U 3 years No difference in terms of clinical result |

|

| Subramonia S, Lees T. Radiofrequency ablation vs conventional surgery for varicose veins-a comparison of treatment costs in a randomized trials. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2009;39:104 | VNUS closure bipolar catheter versus HL (n = 47) vs HL+S (n = 41) RFA was more expensive but return to work was earlier P = 0.006 |

F-U, follow-up; GSV, great saphenous vein; HL, high ligation; QoL, quality of life; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; S, saphenous stripping.

Table 10.4 RCTs of HL+S versus EVLA

| Type of Procedure | Article | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| HL+ S versus EVLA |

Darwood RJ, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation with surgery for the treatment of primary great saphenous veins. Br J Surg 2008;95:294 | 810-nm laser diode stepwise withdrawal (n = 42) and continuous withdrawal (n = 29) versus conventional surgery (n = 32) |

| F-U 3 months Abolition of reflux and improvement in disease specific QoL comparable Earlier return to normal activity with EVLA P = 0.005 |

||

| De Medeiros et al. Comparison of endovenous treatment with an 810-nm laser versus conventional stripping of the great saphenous vein in patients with primary varicose veins. Dermatol Surg 2005;31:1685 | 810-nm laser diode sequential withdrawal (n = 20) versus conventional surgery (n = 20) |

|

| F-U 9 months (mean) Post operative pain comparable Fewer swellings and less bruising after EVLA. P ? More benefits with EVLA. P? |

||

| Kalteis M, Berger I, Messie-Werndl S, et al. High ligation combined with stripping and endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein: early results of a randomized controlled study. J Vasc Surg 2008;47:822 | 810-nm laser diode sequential withdrawal + HL (n = 47) versus conventional surgery (n = 48) | |

| F-U 4 month Hematomas smaller with EVLA. P = 0.001 EVLA was associated with a longer period of time until return to work P = 0.054 No difference in terms of health related QoL (CIVIQ) |

||

| Rassmussen et al. Randomized trial comparing endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein with ligation and stripping in patients with varicose veins: short-term results. J Vasc Surg 2007;46:308 | 980-nm laser diode pulse mode (n = 62) versus conventional surgery (n = 59) | |

| F-U 6 months Short-term efficacy and safety are similar. Except for slightly increased postoperative pain and bruising in HL+S group no differences were found |

||

| EVLA versus cryostripping | Disselhoff BCVM, der Kinderen DJ, Moll FL. Is there a risk for lymphatic complications after endovenous laser treatment versus cryostripping of the great saphenous vein? A prospective study. Phlebology 2008;23:10-4 | 810-nm laser diode withdrawal mode not mentioned 17 EVLA (n = 17) vs cryostripping (n = 16) |

| F-U 6 months One complication lymphedema after cryostripping |

||

| Disselhoff BCVM, der Kinderen DJ, Kelder JC, Moll FL. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser with cryostripping for great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg 2008;95:1232-8 | 810-nm laser diode withdrawal mode not mentioned EVLA (n = 46) versus cryostripping (n = 46) |

|

| F-U 2 years With EVLA less postoperative pain P = 0.003 Return to normal activity shorter P = 0.002 Clinical and hemodynamic outcome no difference |

||

| Disselhoff BCVM, Buskens E, Kelder JC, der Kinderen DJ, Moll FL. Randomized comparison of Costs and Cost-effectiveness of cryostripping and Endovenous Laser ablation for Varicose veins: 2-year results. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2009;37:357-63 | 810-nm laser diode withdrawal mode not mentioned 60 EVLA (n = 60) versus cryostripping (n = 60) |

|

| F-U 2 yearsOutpatient cryostripping less costly and more effective P = ns |

EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; F-U, follow-up; HL, high ligation; QoL, quality of life; S, saphenous stripping.

Table 10.5 RCTs of HL+S versus surgery preserving the GSV

| Type of Procedure | Article | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| HL+S+ Perforator ligation versus HL + tributary phlebectomy +/– perforator ligation |

Campanello M, et al. Standard stripping versus long saphenous vein saving surgery for primary varicose veins: a prospective, randomized study with the patients as their own controls. Phlebology 1996;11:45 | HL + tributary phlebectomy+ perforator ligation (n = 18 group 1) versus HL+ stripping + tributary phlebectomy + perforator ligation (n = 18 group 2) Post operative course Less subjective post operative discomfort |

| F-U 4 years No difference in terms of clinical outcome and plethysmography GSV compressible and patent when preserved |

||

| Dwerryhouses et al. Stripping the long saphenous vein reduces the rate of reoperation for recurrent varicose veins. J Vasc Surg 1999;29:589 Winterborn RJ, et al. Causes of varicose vein recurrence: late results of a randomized controlled trial of stripping the long saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg 2004;40:34 |

HL + tributary phlebectomy (n = 58) versus HL+ stripping + tributary phlebectomy (n = 52) | |

| At F-U 5 and 11 years No difference in terms of recurrence but in the group with preservation of the saphenous trunk redo surgery was performed more frequently P = 0.012 |

||

| HL+S versus CHIVA |

Carandinas et al. Stripping versus haemodynamic correction (CHIVA): a long term randomised trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008;35:230-7 | HL+S (n = 75) versus CHIVA (n = 75) |

| 10 years F-U With CHIVA Less recurrence P = 0.04 |

||

| Parés JO, Juan J, Tellez R, Mata A, Moreno C, Quer FX et al. Varicose vein surgery. Stripping versus the CHIVA method : a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2010;251:624-31 | 501 patients C2-C6 randomized in 3 groups – HL+ Stripping with clinic marking (S-CM group n =167) – HL+ stripping with duplex marking (S-DM group n = 167) versus CHIVA group n = 167) |

|

| 5 years F-U CHIVA > HL+ stripping in terms of recurrence P < 0.001 |

F-U, follow-up; HL, high ligation; S, saphenous stripping

Table 10.6 RCTs of HL+S versus foam sclerotherapy

| Type of Procedure | Article | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| CA + HL versus HL+S |

Bountouroglou DG, Azzam M, Kakkos SK, et al. Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy combined with sapheno-femoral ligation compared to surgical treatment of varicose veins: early results of a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006;31:93 | Liquid sclerotherapy + HL (n = 30) versus HL+S (n = 30) |

| F-U 3 months Early recanalization in 13% after CA treated by complementary injection |

||

| CA+HL less expansive, more rapid return to normal activities P < 0.0001 | ||

| No difference in term of complication and occlusion | ||

| Abela R, Liamis A, Prionidis I, et al. Reverse foam sclerotherapy of the great saphenous vein with sapheno-femoral ligation compared to standard and invagination stripping: a prospective clinical series. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008;36:485 | HL+ reverse foam sclerotherapy (n = 30), HL + cryostripping (n = 30), HL+S (n = 30) | |

| HL+ reverse foam sclerotherapy less post operative complication and better patient satisfaction | ||

| CA versus HL+S |

Figueiredo M, Araujo S, Barros N Jr, Miranda F Jr. Results of surgical treatment compared with ultrasoundguided foam sclerotherapy in patients with varicose veins: a prospective randomised study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2009;38:758 | Foam sclerotherapy (n = 27) 1–3 sessions 10 mL/session vs HL+S (n = 29) in C5 patients |

| F-U 6 months Vein obliteration AC 78%, HL+S 90%. P = ns related to the small number of patients included |

CA, chemical ablation; F-U, follow-up; HL, high ligation; S, saphenous stripping.

Classical surgery variants

Saphenous trunk stripping with preservation of the saphenofemoral confluence +/− incompetent tributaries phlebectomy +/− incompetent perforator interruption

A retrospective cohort study of 151 patients (175 lower limbs C1 = 1.5%, C2 = 82.1%, C3 = 6.7%, and C4-6 = 9.7%) were treated as mentioned above knowing that 68.1% were symptomatic. The preoperative DSU showed that both saphenofemoral confluence (SFC) and saphenous trunk were incompetent. At a mean of 24.4 months postoperatively (median 27.3 months, range 8 to 34.8), persistent SFC reflux was observed in only two cases (1.8%) and a SFC neovascularization in one case (0.9%). Recurrence of VVs appeared in seven cases (6.3%) but in conjunction with SFC reflux in only one case. Post treatment 83.9% of limbs were converted to CEAP clinical class 0 to 1 and significant symptom improvement was observed in 91.3% of cases with an esthetic benefit in 95.5%.14

There is no RCT comparing this method to other operative treatments.

Surgery with saphenous trunk preservation

SFJ and/or SPJ ligation plus incompetent tributaries phlebectomy with or without incompetent perforator interruption

In addition to observational studies, two RCTs are available that include patients presenting with SFC and saphenous trunk incompetence (see Table 10.5).16,17,69 It is not clear whether this procedure provides better results than the ASVAL method (see below).

Apart from in one study,16 the quality of the preserved saphenous trunk to be used as an arterial substitute has never been assessed in depth.

SFJ wrapping or valvuloplasty plus incompetent tributaries phlebectomy with or without incompetent perforator interruption

Some observational studies have been reported claiming both good clinical and hemodynamic results for this procedure.21,22 Again, it is not known whether this procedure produces better results than ASVAL nor whether the quality of the preserved saphenous trunk is suitable for use as an arterial substitute.

Hook phlebectomy or powered phlebectomy

According to the RCTs there is no evident benefit in using powered phlebectomy (Tables 10.6 and 10.7).75–77

Table 10.7 RCTs of hook phlebectomy versus powered phlebectomy

| Type of Procedure | Article | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Hook phlebectomy versus Trivex |

Aremu M, Mahendran B, Butcher W, et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial: conventional versus powered phlebectomy. J Vasc Surg 2004;39:88 | No difference in terms of patient satisfaction and cosmetic result |

| Scavée V, Lesceu O, Theys S, et al. Hook phlebectomy versus transilluminated powered phlebectomy for varicose veins surgery. Early results. Eur J Vasc Surg 2003;25:473 | ||

| Ray-Chaudury SB, Huq Z, Souter RG, McWhinnie D. A randomized controlled trial comparing transilluminated powered phlebectomy with hook avulsions: an adjunct to day surgery. One Day Surg 2003;13:24 | No difference in postoperative pain |

Trivex (InaVein LLC, Lexington, Mass.)

Varices phlebectomy with conservation of the refluxing saphenous trunk

When, preoperatively, reflux in the saphenous trunk extended from its termination to the malleolus, the elimination of the ST reflux was less frequent (47.6% vs 70.3%; P < .05).31

CHIVA method

A great number of observational studies, mostly retrospective by Italian and Catalonian teams, have been reported. Their analyses are sometimes difficult for other practitioners to understand, owing to the use of the specific CHIVA terminology and the modification of the technique itself, but CHIVA protagonists are happy with this method if the preoperative hemodynamic shunt type (CHIVA language) has been correctly identified. Two long-term RCTs are available that supports its use (see Table 10.6).71

Indications for Surgery

In absence of long-term follow-up RCTs evaluating the different treatment methods including surgery, only weak recommendations according to Guyatt77 can be stated. Nevertheless, it appears that surgery is presently giving way to minimally invasive procedures; that is to say chemical and thermal ablation. In Europe, surgery with preservation of the saphenous trunk (including ASVAL and CHIVA) has some supporters.

Indications according to the clinical presentation

Clinical presentation may sometimes influence the indication.

Pregnancy

In women, pregnancy may influence the indication. It has been established that the REVAS risk after GSV conventional surgery in a woman who has already had a child is higher in subsequent pregnancies.79 If an operative treatment is decided upon then a less invasive procedure is recommended, such as combining it with chemical or thermal ablation in order to avoid open surgery at the groin.

Association of VV with another disease

Indications according to the CEAP class

In the C2 class (non-complicated VVs) there is no argument that favors surgery to other operative treatments. In complicated VVs, particularly in C6 patients, only RCTs comparing classical surgery to conservative treatment are available,50–52 apart from one small series involving treatment with CHIVA.79 That does not demonstrate that classical surgery provides a better outcome in patients presenting with venous ulcer, as observational studies with thermal and clinical ablation include C6 patients.81

Indications according to anatomic and physiopathologic anomaly

Reflux at the SFJ and/or at the SPJ

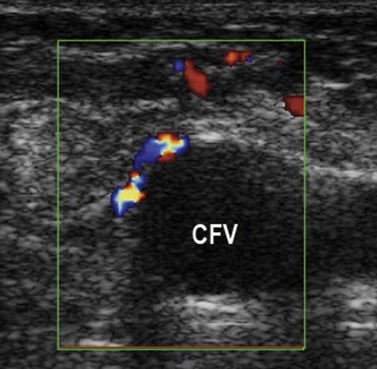

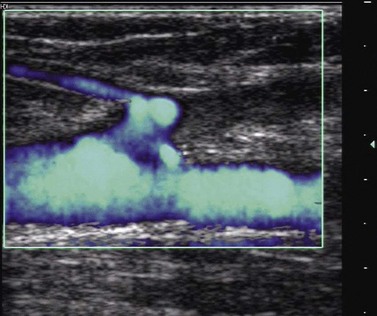

In theory, with major reflux at the SFJ or SPJ (particularly when the terminal valve is incompetent and the terminal portion of the saphenous trunk very enlarged), classical surgery is the best option as HL+S are supposed to solve the problems. This recommendation was stated by Cappelli but no data support it.12 However, patients with an incompetent terminal valve treated with preservation of the SFJ had a good outcome in the Pittaluga’s series.14 Furthermore, outcome in patients treated using thermal ablation by RF with preservation of the SFJ was as good as after classical surgery at 5 years.53,54,82 In any case, SFJ has been examined at a median follow-up of 25 months by DUS and the most common finding in the groin was an open, competent SFJ with a greater than 5-cm patent terminal GSV segment conducting prograde tributary flow through the SFJ (82%) (Fig. 10.16).83

Figure 10.16 DUS. Physiological drainage of the superficial epigastric vein in the stump of the SFJ after radiofrequency ablation.

(From Perrin M. Traitement chirurgical endovasculaire des varices des membres inférieurs. Techniques et résultats. EMC (Elsevier Masson SAS, Paris), Techniques chirurgicales – Chirurgie vasculaire, 43-161-C, 2007).

Knowing that neovascularization at the groin is frequent and the major cause of recurrence at the SFJ after HL13,54,83,84 (Fig. 10.17), whatever the pathophysiology, is inconclusive; there is no RCT comparing saphenous trunk stripping with and without HL.

Combination of primary deep reflux and primary varices

When primary deep reflux (PDR) is sequential there is a large consensus to consider that it does not modify the indication for VV treatment. Conversely, when PDR is axial and in the presence of severe chronic venous insufficiency (C4b, C6), and particularly with recurrent ulceration, valvuloplasty must be considered in the patient reluctant to wear stockings or non-compliant to compression.85

Combination of primary deep obstruction and primary varices

According to Raju and Neglen primary iliac obstruction is frequently associated with varices in patients with severe venous symptoms or chronic venous insufficiency. When patients are not improved by complete VV treatment, investigation of the iliac vein is recommended to identify obstruction and possible stenting.86,87

1 Abu-Own A, Scurr JH, Coleridge-Smith PD. Saphenous vein reflux without incompetence at the saphenofemoral junction. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1452.

2 Labropoulos N, Delis K, Nicolaides AN, et al. The role of the distribution and anatomic extent of reflux in the development of signs and symptoms in chronic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 1996;23:504.

3 Labropoulos N, Giannoukas AD, Delis K, et al. Where does venous reflux start? J Vasc Surg. 1997;26:736.

4 Labropoulos N, Kang SS, Mansour MA, et al. Primary superficial vein reflux with competent saphenous trunks. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;18:201.

5 Labropoulos N, Leon L, Kwon S, et al. Study of the venous reflux progression. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:291.

6 Engelhorn CA, Engelhorn AL, Cassou MF, Salles-Cunha SX. Patterns of saphenous reflux in women with primary varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:645.

7 Garcia Gimeno M, Rodriguez-Camarero S, Tagarro-Villalba, et al. Duplex mapping of 2036 varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:681.

8 Lim CS, Davies AH. Pathogenesis of primary varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1231.

9 Stuart WP, Adam DJ, Allan P, et al. Saphenous surgery does not correct perforator incompetence in the presence of deep vein reflux. J Vasc Surg. 1998;28:834.

10 Campbell WA, West A. Duplex ultrasound audit of operative treatment of primary varicose veins. Phlebol. 1995;1(Suppl):407.

11 Pichot O, Sessa C, Bosson JL. Duplex imaging analysis of the long saphenous vein reflux: basis for strategy of endovenous obliteration treatment. Int Angiol. 2002;21:333.

12 Cappelli M, Molino Lova R, et al. Hemodynamics of the sapheno-femoral junction patterns of reflux and their clinical implications. International Angiol. 2004;23:25-28.

13 Jones L, Braithwaite BD, Selwyn D, et al. Neovascularisation is the principal cause of varicose vein recurrence: results of a randomised trial of stripping the long saphenous vein. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;12:442-445.

14 Pittaluga P, Chastanet S, Guex JJ. Great saphenous vein stripping with préservation of sapheno-femoral confluence: Hemodynamic and clinical results. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:1300.

15 Hammarsten J, Pederson P, Cederlund C-G, Campanello M. Long saphenous vein saving surgery for varicose vein: a long term follow-up. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1990;4:361.

16 Campanello M, Hammarsten J, Forsberg C, et al. Standard stripping versus long saphenous vein saving surgery for primary varicose veins: a prospective, randomized study with the patients as their own controls. Phlebology. 1996;11:45.

17 Dwerryhouse S, Davies B, Harradine K, Earnshaw JJ. Stripping the long saphenous vein reduces the rate of reoperation for recurrent varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 1999;29:589.

18 Figelstone L, Carolan G, Pugh N, et al. An assessment of the long saphenous vein for potential use as a vascular conduit after varicose vein surgery. J Vasc Surg. 1993;18:836.

19 Agus GB, Bavera PM, Mondani P, Santuari D. External valve-support (EVS) for saphenofemoral junction incomptence. Randomized trial at 3 years follow-up. Acta Phlebolog. 2002;3:101.

20 Corcos L, De Anna D, Zamboni P, et al. Reparative surgery of valves int the treatment of superficial venous insufficiency. External banding valvuloplasty versus High ligation or disconnection. A prospective multicentric trial. JMV. 1997;22:2.

21 Lane RJ, Graiche JA, Coroneos JC, Cuzilla ML. Long term comparison of external valvular stenting and stripping of varicose veins. ANZJ Surg. 2003;73:605.

22 Sakatowa H, Hoshino S, Igari T, et al. Angioscopic external valvuloplasty in the treatment of varicose veins. Phlebology. 1997;12:136.

23 Belcaro G, Errichi BM. Selective saphenous valve repair: a 5-year follow-up study. Phlebology. 1992;7:121.

24 Geier B, Voigt I, Marpe P, et al. External valvuloplasty in the treatment of greater saphenous vein insufficiency: a five-year follow-up. Phlebology. 2003;18:137.

25 Corcos L, Procacci T, Peruzzi G, et al. External valvuloplasty of the sapheno-femoral junction versus high ligation or disconnection. Phlebol. 1996;25:2.

26 Muller R. [in French]. Traitement des varices par la phlébectomie ambulatoire. Phlébologie. 1966;19:277.

27 Ricci S. Ambulatory phlebectomy: principles and évolution of the method. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:459.

28 Goldman MP, Geogiev M, Ricci S. Ambulatory phlebectomy: a practical guide for treating varicose veins, 2nd ed. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis; 2005.

29 Olivencia JA. Maneuver to facilitate ambulatory phlebectomy. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:654.

30 Muller R. (in French) Mise au point sur la phlébectomie ambulatoire. Phlébologie. 1996;49:335.

31 Pittaluga P, Chastanet S, Rea B, Barbe R. Midterm results of the surgical treatment of varices by phlebectomy with conservation of a refluxing saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:107.

32 Creton D. Diameter reduction of the proximal long saphenous vein after ablation of a distal incompetent tributary. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:394.

33 Franceschi C. Théorie et pratique de la cure conservatrice et hémodynamique. Editions de l’Armançon; 1988.

34 Franceschi C, Zamboni P. Principles of venous hemodynamics. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Publishers; 2009.

35 Cohn MS, Seiger E, Goldman S. Ambulatory phlebectomy using the tumescent technique for local anesthesia. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:315.

36 Bush RG, Hammond KA. Tumescent anesthetic technique or long saphenous stripping. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;9:626.

37 Keel D, Goldman MP. Tumescent anesthesia in ambulatory phlebectomy: addition of epinephrine. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:371.

38 Smith SR, Goldman MP. Tumescent anesthesia in ambulatory phlebectomy. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:453.

39 Critchley G, Handa A, Maw A, et al. Complications of varicose vein surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1997;79:105.

40 Miller GV, Lewis WG, Sainsbury JR, Macdonald RC. Morbidity of varicose vein surgery: auditing the benefit of changing clinical practice. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1996;78:345.

41 Morrison C, Dalsing MC. Signs and symptoms of saphenous nerve injury after greater saphenous vein stripping: prevalence, severity and relevance for modern practice. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:886.

42 Sam RC, Silverman SH, Bradbury AW. Nerve injuries and varicose vein surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;27:13.

43 Subramonia S, Lees T. Sensory abnormalities after long saphenous stripping: impact on short-term quality of life. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:510.

44 Van Rij AM, Chai G, Hill GB, Christie RA. Incidence of deep vein thrombosis after varicose vein surgery. B J Surg. 2004;91:1582.

45 Lemasle P, Lefebvre-Vilardebo M, Uhl JF, et al. Faut-il vraiment prescrire des anticoagulants après chirurgie d’exérèse des varices? Résultats d’une étude prospective portant sur 4206 interventions. Phlébologie. 2004;57:187.

46 Beale RJ, Gough MJ. Treatment options for primary varicose veins: a review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;30:83.

47 Campbell WB, Decaluwe H, Boecxstaens V, et al. The symptoms of varicose veins: difficult to determine and difficult to study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34:741-744.

48 Michaels JA, Brazier JE, Campbell WB, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing surgery with conservative treatment for uncomplicated varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2006;93:175.

49 Ratcliffe J, Brazier JE, Campbell WB, et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of surgery versus conservative treatment for uncomplicated varicose veins in a randomized control trial. Br J Surg. 2006;93:182.

50 Guest M, Smith JJ, Tripuraneni G, et al. Randomized clinical trial of varicose vein surgery with compression versus compression alone for the treatment of venous ulceration. Phlebology. 2003;18:130-136.

51 Gohel MS, Barwell JR, Earnshaw JJ, et al. Randomized clinical trial of compression + surgery versus compression alone in chronic venous ulceration.(ESCHAR study)-haemodynamic and anatomic changes. Br J Surg. 2005;92:291.

52 Gohel MS, Barwell JR, Taylor M, et al. Long term results of compression therapy alone versus compression plus surgery in chronic venous ulceration (ESCHAR): randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335:83.

53 Kostas T, Loannou CV, Toulouopakis E, et al. Recurrent varicose veins after surgery: a new appraisal of a common and complex problem in vascular surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;27:275.

54 Van Rij AM, Jiang P, Solomon C, et al. Recurrence after varicose vein surgery: A prospective long-term clinical study with duplex ultrasound scanning and air plethysmography. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:935.

55 Perrin M, Guex JJ, Ruckley CV, et al. Recurrent varices after surgery (REVAS), a consensus document. Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;8:233.

56 Menyhei G, Gyevnár Z, Arató E, et al. Conventional stripping versus cryostripping: a prospective randomised trial to compare improvement in quality of life and complications. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:218.

57 Taco MAL, et al. A randomized trial of cryostripping versus conventional stripping of the great saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:403.

58 Hinchliffe RJ, Ubhi J, Beech A, et al. A prospective randomised controlled trial of VNUS Closure versus surgery for the treatment of recurrent long saphenous varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:212.

59 Kianifard B, Holdstock JM, Whiteley MS, et al. Radiofrequency ablation (VNUS Closure) does not cause neo-vascularisation at the groin at one year: results of a case controlled study. Surgeon. 2006;4:71.

60 Lurie F, Creton D, Eklof B, et al. Prospective randomized study of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration (closure procedure) versus ligation and stripping in a selected patient population (EVOLVES Study). J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:207.

61 Lurie F, Creton D, Eklof B, et al. Prospective randomized study of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration (closure) versus ligation and vein stripping (EVOLVeS): two-year follow-up. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;29:67.

62 Rautio T, et al. Endovenous obliteration versus conventional stripping operating in the treatment of primary varicose veins: a randomized controlled trial with comparison of the costs. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:958.

63 Perälä J, Rautio T, Biancari F, et al. Radiofrequency endovenous obliteration versus stripping of the long saphenous vein in the management of primary varicose veins: 3-year outcome of a randomized study. Ann Vasc Surg. 2005;19:1.

64 Subramonia S, Lees T. Radiofrequency ablation vs conventional surgery for varicose veins – a comparison of treatment costs in a randomized trials. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;39:104.

65 Darwood RJ, Theivacumar N, Dellagrammaticas D, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation with surgery for the treatment of primary great saphenous veins. Br J Sug. 2008;95:294-301.

66 de Medeiros CAF, et al. Comparison of endovenous treatment with an 810 nm laser versus conventional stripping of the great saphenous vein in patients with primary varicose veins. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1685.

67 Kalteis M, Berger I, Messie-Werndl S, et al. High ligation combined with stripping and endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein: early results of a randomized controlled study. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:822.

68 Rassmussen LH, Bjoern L, Lawaetz M, et al. Randomized trial comparing endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein with ligation and stripping in patients with varicose veins: short-term results. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:308.

69 Winterborn RJ, Foy C, Earnshaw JJ. Causes of varicose vein recurrence: late results of a randomized controlled trial of stripping the long saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:34.

70 Carandina S, Mari C, De Palma M, et al. Stripping vs haemodynamic correction (CHIVA): a long term randomised trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:624.

71 Parés JO, Juan J, Tellez R, et al. Varicose vein surgery. Stripping versus the CHIVA method: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2010;251:624-631.

72 Bountouroglou DG, Azzam M, Kakkos SK, et al. Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy combined with sapheno-femoral ligation compared to surgical treatment of varicose veins: early results of a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:93.

73 Abela R, Liamis A, Prionidis I, et al. Reverse foam sclerotherapy of the great saphenous vein with sapheno-femoral ligation compared to standard and invagination stripping: a prospective clinical series. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:485.

74 Figueiredo M, Araujo S, Barros NJr, Miranda FJr. Results of surgical treatment compared with ultrasoundguided foam sclerotherapy in patients with varicose veins: a prospective randomised study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:758.

75 Aremu M, Mahendran B, Butcher W, et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial: conventional versus powered phlebectomy. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:88.

76 Scavée V, Lesceu O, Theys S, et al. Hook phlebectomy versus transilluminated powered phlebectomy for varicose veins surgery. Early results. Eur J Vasc Surg. 2003;25:473.

77 Ray-Chaudury SB, Huq Z, Souter RG, McWhinnie D. A randomized controlled trial comparing transilluminated powered phlebectomy with hook avulsions: an adjunct to day surgery. One Day Surg. 2003;13:24.

78 Guyatt G, Gutterman D, Baumann MH, et al. Grading strength of recommendations and quality of evidence in clinical guidelines: report from an American College of Chest Physicians Task Force. Chest. 2006;129:174.

79 Fischer R, Chandler JG, Stenger D, et al. Patients characteristics and physician-determined variables affecting saphenofemoral reflux recurrence after ligation and stripping of the great saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:81.

80 Zamboni P, Cisno C, Marchetti P, et al. Hemodynamic CHIVA correction versus compression for primary venous ulcers: first year results. Phlebology. 2004;19:28.

81 Vasquez MA, Wang J, Mahathanaruk M, et al. The utility of venous clinical severity score in 682 limbs treated by radiofrequency saphenous ablation. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:1008.

82 Merchant RF, Pichot O for the Closure Study Group. Long-term outcomes of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration of saphenous reflux as a treatment for superficial venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:502.

83 Pichot O, Kabnick LS, Creton D, et al. Duplex ultrasound scan findings two years after great sapenous vein radiofrequency endovenous obliteration. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:189.

84 van Rij AM, Jones GT, Hill GB, Jiang P. Neovascularization and recurrent varicose veins: more histologic and ultrasound evidence. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:296.

85 Perrin M. Deep venous reconstructive surgeryto treat reflux in the lower extremities. Phlebolymphology. 2005;49:375.

86 Neglen P, Hollis KC, Raju S. Combined saphenous ablation and iliac stent placement for complexe severe chronic disease. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:828.

87 Raju S, Neglen P. High prevalence of nonthrombotic iliac vein lesions in chronic venous disease: a permissive role in pathogenicity. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:136.