Chapter 15 Risk of violence

The most effective response to the risks of dangerous behaviour in the mentally ill is not to return to policies of greater control and containment but to improve the care, support and treatment delivered to patients in the community.1

Violence is probably the most difficult risk for mental health clinicians to assess. Whereas suicide and self-harm are very closely aligned with mental illness, violence is not. Suicide and self-harm assessments are the bread and butter of a clinician’s work. Whilst violence assessments are less common for a general mental health clinician, they are routine for clinicians working in forensic settings. To further complicate matters, the assessment of violence in a forensic setting usually occurs after the event and takes place in a relatively controlled environment. For a general clinician, assessments for violence occur in a setting which is more fluid and in which there may have been no previous violence: altogether a different world. However, research which has occurred predominantly in forensic settings has much to offer mainstream mental health workers.

Most violence is perpetrated by those who are not mentally ill. Some understanding of the pathways leading to violence in those who are not mentally ill is a prerequisite for the comprehension of violence when the presentation is complicated by mental illness. Within mental health, De Zulueta’s book (1993), From Pain to Violence: The Traumatic Roots of Destructiveness2 is an excellent introduction to the subject. She explores the origins of human aggression and violence, and its links with attachment and trauma. Violence and its association with risk is covered in detail in Maden’s book (2007)3 and should be consulted for a more intensive analysis of the brief introduction in this chapter.

Introduction

Physical aggression peaks at perhaps around the second year of life and subsequently shows distinct developmental trajectories in different individuals.4 Aggression is a problem which is present from early childhood, arguably from toddlerhood and perhaps from birth. Violence ultimately signals the failure of normal developmental processes to deal with something (aggression) that occurs naturally.5 With this in mind, it will be important when assessing an individual’s risk of violence to consider their developmental pathway. This will have influenced their potential for destructiveness as a result of an inability to manage aggressive impulses. Rutter et al (2001) showed that environmental influences that divert the child from paths of violence and behavioural disturbance often imply the establishment of strong attachment relationships with relatively healthy individuals.6 The common pathway to violence is the momentary inhibition of the capacity for communication or for interpretation. It probably could not arise if early experience has built an interpersonal interpretive capacity of sufficient robustness to withstand later maltreatment.7

There has been substantial discussion in the literature about whether mental illness does increase the risk of violence and, currently, the consensus seems to be that there is a slightly increased risk but it is small.8,9,10 Early work on the risk of violence in the mentally ill focussed mostly on its prediction and was carried out predominantly in forensic settings. Inquiries into homicide by persons with mental illness found that only a minority of incidents were predictable. Despite this, the majority could have been prevented with good risk management.11,12 Current recommendations are that the only ethical justification for the assessment of the risk of violence is when risk reduction through risk management is also included.13 The two areas in psychiatry in which violence has been studied most intensively are for those patients suffering from schizophrenia and for those patients with personality disorders, especially psychopathy. The trends which are emerging from the study of these two areas are likely to be applicable to other disorders.

BOX 15.1 AGGRESSION AND VIOLENCE: SUMMARY

• Aggression is a normal component of human functioning.

• Violence can be seen as the inability to control aggression or the use of aggression for personal gain.

• Failure to develop secure attachments is a risk factor for violence.

• Some cultures have a tradition of greater use of violence. It is necessary to factor this into history taking.

• Mental illness causes a slight increase in the risk of violence.

Risk factors for violence not always associated with mental illness

Many non-psychiatric variables, especially a combination of youth, male gender, substance use and low socioeconomic status, reveal a far greater association with violence than does mental illness.14 Applying risk factors, especially static ones, in an unthinking way should be avoided. Simply to assume that maleness, for example, will lead to violence is not helpful. In the debate about which static risk factors to include in standardised rating scales, it is pertinent to note that male gender and youth have been left out of the Historical/Clinical/Risk Management 20-item (HCR 20) scale. The risk factors of most relevance in helping predict the future, longer-term risk of violence are those not necessarily associated with mental illness: the two most important static factors being substance misuse15,16 and a past history of violence.17 Drugs and alcohol are strongly associated with violent behaviour.18 The majority of persons involved in violent crimes are under the influence of alcohol at the time of their aggression.19 At least half of all violent events, including murders, were preceded by alcohol consumption by the perpetrator of a crime, the victim or both.20 Stimulants which increase aggressiveness, grandiosity and paranoia, such as amphetamines and cocaine, are of special concern. Among psychiatric patients, a coexisting diagnosis of substance abuse is strongly predictive of violence.21

BOX 15.2 RISK FACTORS FOR VIOLENCE – NON MENTAL ILLNESS

• Most violence is perpetrated by those who are not mentally ill.

• Substance abuse and a past history of violence are the two most important static risk factors for violence.

• Alcohol and stimulants are the two drug groups most implicated when violence occurs.

• A detailed history of past episodes of violence is a prerequisite of an assessment of risk of violence.

Schizophrenia and violence

For violent behaviour, reports typically find that schizophrenia is related to a 4–6-fold increased risk of violent behaviour, which has led to the view that schizophrenia and other major mental disorders are preventable causes of violence and violent crime.22 There has been considerable uncertainty about what mediates this elevated risk. Studies have begun to characterise a subpopulation of patients with schizophrenia whose course of illness and treatment is shaped by a complex developmental trajectory — the intertwining of psychosis with the sequelae of childhood antisocial conduct, trauma, victimisation and substance abuse. At the centre of this knot of pathologies lies the problem of violent behaviour.23 Violence among adults with schizophrenia may follow two distinct pathways — one associated with premorbid conditions, including antisocial conduct, and the other associated with the acute psychopathology of schizophrenia.24 For some time, it was felt that violence was predominantly mediated by the active symptoms of illness — mostly psychosis,25 but more recently it appears that the association of schizophrenia and violence disappears when substance abuse is accounted for.26 Similarly, if there is a history of conduct disorder, the likelihood of violence in schizophrenia is greater.27 However, positive psychotic symptoms have been linked to violence in a group without conduct problems.28

Regarding homicide, there is some evidence of an increased risk in patients suffering from schizophrenia. In Shaw’s paper from 2006, a rate of schizophrenia of 5% (lifetime) was found out of 1594 people convicted of homicide over a 3-year period.29

Psychosis and violence

Although the literature on this subject can be confusing at times, there is general, clinical consensus that acute symptoms of illness, mostly psychosis, are linked to an increased risk of violence.30

Delusions noted to increase the risk of violence are those characterised by having ‘threat/control override’ (TCO) symptoms.31 These involve the following characteristics:

• that the mind is dominated by forces beyond the person’s control

• that thoughts are being put into the person’s head

Also, when delusional beliefs make subjects unhappy, frightened, anxious or angry, they are more likely to act aggressively. Non-delusional suspiciousness, such as misperceiving others’ behaviour as indicating hostile intent, is also associated with subsequent violence.32 A propensity to act on delusions in general is significantly associated with a tendency to commit violent acts.33

In general, the presence of hallucinations is not related to dangerous acts but in patients with schizophrenia; they are more likely to be violent if their hallucinations generate negative emotions such as anger, anxiety or sadness. The risk of violence is also greater if the patient has not developed successful strategies to cope with their voices.34 There is a relationship between command hallucinations to commit violence and actual violence.35 Lack of insight is also important.36

In the assessment, an attempt should be made to link symptoms with behaviour. Delusions and hallucinations are obviously important, but over-arousal, disinhibition and extremes of fear or anger are probably more common links between mental disorder and violence.37

BOX 15.4 VIOLENCE AND PSYCHOSIS: SUMMARY

• A past history of violence and/or substance abuse is of more predictive value than a history of psychosis.

• A childhood history of conduct disorder and/or failure of attachments is of substantial importance.

• Psychosis leading to fear, anger, over arousal and other emotional states is likely to be a common link between mental disorder and violence.

• Psychosis which is perceived by the patient as threatening and leads to a decision to ‘override’ normal inhibitory controls is of importance.

• A tendency to act on delusions is linked to violence.

• Command hallucinations to commit violence are a risk factor.

• There are likely to be two pathways leading to violence: one associated with premorbid conditions and the other with acute symptoms.

• Non-compliance with medication putting the patient at risk of a relapse of psychosis is of great importance.

Personality disorders and violence

The most common personality disorder associated with violence is antisocial personality disorder (ASPD).38 However, this may be misleading as the majority of the research on personality disorders and violence has been carried out using the concept of psychopathy and especially the Hare Psychopathy Checklist, Revised (PCL-R).39 There is an important difference between these two diagnoses. ASPD is predominantly based on behavioural manifestations whilst psychopathy utilises interpersonal, affective, lifestyle and antisocial constructs.40 The construct of psychopathy does not exist within either DSM IV41 or ICD 10,42 which creates further problems for clinicians.

The interpersonal and affective components are seen as being central features to the construct of psychopathy. It is wrong to equate research on the risk of violence in psychopathy to violence in a patient with a diagnosis of ASPD. The diagnosis of ASPD is much more common than that of psychopathy and occurs approximately three times more frequently.43 Similar arguments can be made between the diagnosis of dissocial personality disorder (ICD-10) and psychopathy.44 Although the PCL-R and the Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL: SV) are among the best predictors of risk for offending and risk for violence in psychiatric patients,45 contemporary approaches to risk assessment require that these measures are not employed in isolation.46 The rate of psychopathy in psychiatric populations is very low (i.e. approximately 1–2%) but it is important to emphasise the strong predictive quality of the Hare Psychopathy Checklist.47 Unfortunately, using the Hare Psychopathy Checklist requires training and experience in psychopathology, psychometric assessment and the research in the field of psychopathy. However, knowledge of the findings from this work can be useful in everyday assessments.

The violence perpetrated by those with psychopathy is often motivated by revenge or occurs during a period of heavy drinking. Violence amongst these persons is frequently cold and calculated and lacks emotion.48 The differentiation between affective and predatory violence47 is a useful one to make. Affective aggression involves hostile behaviour as a reaction to some perceived threat, either from the environment or from an internal sense of fear or anxiety. In contrast, predatory aggression is planned, purposeful and goal directed. Here the individual seeks a target to harm.50 Predatory violence is more dangerous because there is usually an absence of observable antecedent behaviours that foreshadow the aggression.51

Within a mental health setting, traits of personality disorders can emerge with the onset or a relapse of different illnesses. For example, a patient with mania or schizophrenia can present with features of ASPD or psychopathy whilst suffering from an acute relapse of their illness. This becomes important in risk management as the features of personality disorder can at times lead clinicians to forget or ignore the aspects of their Axis I illness and miss out on some of the important risk factors. At its worst, the patient may be misdiagnosed as having a personality disorder and the Axis I disorder is missed entirely. (Personality disorders are classified under Axis II in the DSM IV multi-axial classification system.52 Axis I disorders, which include major mental disorders, should always be considered.) In a similar vein, patients are sometimes misdiagnosed as having a drug-induced psychosis when any substance abuse is noted, which can lead to pejorative, stigmatised approaches by clinicians who then mismanage both the underlying illness and the risk issues.

Other disorders and violence

Depression may result in violent behaviour under certain circumstances. For example, individuals who are depressed may strike out against others in despair. After committing a violent act, the depressed person may attempt suicide; for example, the psychotically depressed

BOX 15.5 VIOLENCE AND PERSONALITY DISORDERS: SUMMARY

• Violence is strongly linked with the diagnosis of psychopathy.

• In these patients, the violence is often cold and calculated and lacks emotion.

• In these patients, the violence is often motivated by revenge or occurs during a period of heavy drinking.

• Violence in patients with a diagnosis of psychopathy is often associated with predatory aggression which is planned, purposeful and goal directed. There is usually an absence of observable antecedent behaviour and the violence is targeted usually at one individual.

• Impulsive violence is more commonly a problem in ASPD compared to the planned violence seen in psychopathy.

• Patients who present with features of personality disorders during an onset or relapse of mental illness should not be treated as if the personality disorder was the primary problem. Active treatment of the Axis I disorder may often lead to the features of personality disorder resolving.

patient who kills his family and then himself. A very important subgroup of depressed patients is those with post-natal depression. There is a small percentage of these patients who develop psychotic symptoms and an even smaller subgroup who develop thoughts of killing their baby (infanticide). This small but significant group of patients need careful and skilled assessment and monitoring.

Morbid jealousy has long been recognised as being a risk factor for violence.

Patients with mania show a high percentage of assaulting or threatening behaviour, but serious violence itself is rare.53

Brain injury or illness should also be considered as a risk factor for aggressive and violent behaviour. After a brain injury or in a delirious state, formerly peaceful individuals may become verbally or physically aggressive. Depending on the site of the injury, patients may lose normal capacity to perceive and process a threat. Impulse controls may have disappeared as a result of the brain injury. For some brain injuries, especially in the amygdala, aggression may be greater than prior to the injury. (The amygdala, part of the limbic system, performs a primary role in the processing and memory of emotional reactions.) In frontal lobe injuries, violence may no longer be linked to shame, guilt or other inhibitory mechanisms that would have been previously present in a patient.

BOX 15.6 VIOLENCE AND OTHER DISORDERS: SUMMARY

• Violence associated with strong affect is often linked to some perceived threat, either from the environment or from an internal sense of fear or anxiety.

• Many psychiatric disorders will be associated with strong affects, including fear, anger, heightened levels of arousal and increased impulsivity. The likelihood of violence will be increased in these circumstances.

• Organic brain disorders may also cause similar disturbance of affective control.

The following list of dynamic risk factors has been proposed for research purposes.54 It is made up from a list of the leading risk factors for violence and they have been selected as they are malleable; that is, they can change with relevant treatment.

Proposed dynamic risk factors

This list covers most of the factors that have been highlighted in the summary boxes. It is necessary to remember that the proposed negative affects would include fear and hyper-arousal. Similarly, it does not elaborate on the specific contents of psychosis which have been discussed and these also need to be remembered. In the summary of risk factors for violence at the end of the chapter (Table 15.1), the static, dynamic and protective factors have been laid out in a form which can be printed on an A4 sheet and used as an aide memoire in the clinical situation. All the risk factors highlighted are included.

| Risk factors for violence |

|---|

| Static factors |

• Psychosis — is the patient threatened, frightened and are normal controls overridden?

• Does the patient feel persecuted?

• Is the patient having command hallucinations?

• Changing symptoms. A tendency to act on symptoms.

• Impulsivity. Lack of insight.

• Violent thoughts being expressed? Morbid jealousy?

• Threatening or fearful behaviour.

• Current diagnosis of personality disorder — especially psychopathy but include antisocial personality disorder.

Screening for assessment for risk of violence

The decision about when to undertake a full assessment of violence is difficult to make. Imminent risk of violence may be mediated and predicted by acute psychiatric symptoms, often in the context of substance use.55,56 It is important to remember that a history of substance use helps predict both future risk and long-term risk, and current substance use helps predict imminent risk.

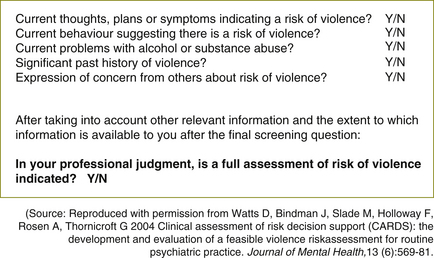

A screening tool was developed at the Institute of Psychiatry, London, in 200257 and may be useful in helping clinicians during an assessment to make a decision about whether to undertake a full risk assessment and management plan. The screening tool forms Figure 15.1.

This screening tool could be used to guide clinicians at times of uncertainty. For certain patients — inpatients, forensic patients — a risk assessment and management plan will automatically be generated, but at other times, these prompts may be of use.

As described elsewhere in this book, the best form of assessment is considered to be structured clinical judgment,58 using a narrative approach.59 In forensic settings, standardised assessment tools are often used to help develop objective risk assessments, monitor treatment, assist in discharge planning and in the development of risk management plans. More recently, scales have been developed to predict violence in inpatient settings. The scales have not focused on any one particular illness but have developed criteria which can be generalised to many acute situations. These are explored in more detail in Chapter 18.

Obtaining a detailed violence history involves determining the type of violent behaviour, asking if weapons were used, why violence occurred, who was involved, the presence of intoxication and the degree of injury. Criminal and court records are particularly useful in evaluating the person’s past history of violence and illegal behaviour. The age at first arrest for a serious offence is highly correlated with persistence of criminal offending.60 Each prior episode of violence increases the risk of a future violent act.

Talking to the patient, relatives and caregivers

The potentially violent patient needs to know and understand why interventions are necessary. Asking a patient about violence has not been shown to increase the likelihood of a violent act occurring and helps establish rapport. Questions about the triggers for violence and a patient’s feelings about being violent give vital information.61 Asking about fantasies, plans to harm others, access to weapons, capacity for self-control and their feelings for their victims adds further important information.62

Violence involves others. Relatives and caregivers often complain of aspects of the patient’s behaviour which, though not involving physical violence, produce fear and distress. All too often this fear-inducing behaviour is dismissed, or minimised, by mental health professionals. Emergence of irritability and threatening and scary behaviours is frequently the way that relapse into delusions and psychotic experiences declares itself.63 Violence is the endpoint of a series of external and internal events. The final releasing factor for the violent event will, of course, vary from person to person, but of immense importance is the risk factors which can be identified, especially critical risk factors unique to the individual. Working with the patient to identify the tipping point for violence is perhaps the central task of the risk assessment and management of violence.

Some patients will continue to behave violently for reasons not felt to be related to their illness or to their treatment. Sometimes this will be driven by psychopathy which is not felt to be treatable in an inpatient setting. At other times there will be discussion about whether the violence is driven by factors such as substance abuse which may be

BOX 15.7 CLINICAL TIP

• If a family member phones and says that they have become frightened about your patient, take note. Fear expressed by the family is often the first indicator of a heightened risk of violence. This should be included in the risk management plan.

• Listening to relatives and other caregivers provides vital information which should not be ignored.

treatable but the patient may decline care. On these occasions, robust discussion within the multidisciplinary team (MDT), with the patient and with their family will often help in clarifying the next step. Utilising a risk/benefit analysis with all concerned can also help. The ethical and moral considerations should be discussed at these times. The guidance of a senior staff member/team leader who is not risk averse at these times is invaluable.

Exercise 1 — identifying personal signals for danger

During the course of the day, you feel as if you make minimal headway. The patient remains uncommunicative but does respond to his name and also when asked to undertake simple tasks such as going to the dining room for a meal, etc. As the shift progresses, you find yourself becoming a little bit uncomfortable and almost frightened in his presence and try and work out why you are feeling this. You note that his eye contact has changed and he now seems to stare at you more intensely. He has begun to pace the corridor and is watching the doorway. Other than this, there are no particular indicators that you can put your finger on, but he seems to become less willing to follow simple directions. On reflection, he reminds you of a similar patient who was violent on the ward 3 months ago. At the end of the shift, you share your concerns with the new staff coming on duty. They apply the Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression (DASA) scale 64 (see Chapter 18, page 191) during their shift and this is repeated on a daily basis. The scores are used to help address the management of the potential risk of violence. As he becomes more communicative, the patient starts to become verbally threatening for a few days, but then this settles. On one occasion he hit the wall with his fist for no apparent reason. When he is able to tell you what was happening, he says that he was very frightened as he felt that he was going to be attacked because of his religious beliefs but could not work out who was going to attack him. He knew that he would have to defend himself if anybody got too close.

Refer to Appendix 3 for a discussion of this exercise.

More prompts and interviewing questions in greater detail can be found in:

• New Zealand Ministry of Health 2006 Assessment and Management of Risk to Others Guidelines; Development of Training Toolkit; and Trainee Workbook. New Zealand Ministry of Health. Online. Available: www.mhwd.govt.nz

• Institute of Psychiatry, London 2002 CARDS assessment guidelines. Health Services Research Department, Institute of Psychiatry, London. Online. Available: www.iop.kcl.ac.uk/iopweb/virtual/?path=/hsr/prism/cards/

1 Mullen P.E. A reassessment of the link between mental disorder and violent behaviour, and its implications for clinical practice. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;31:3–11.

2 De Zulueta F. From Pain to Violence: the Traumatic Roots of Destructiveness. London: Whurr Publishers; 1993.

3 Maden A. Treating Violence: a Guide to Risk Management in Mental Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

4 Nagin D.S., Tremblay R.E. Parental and early childhood predictors of persistent physical aggression in boys from kindergarten to high school. Archives of Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:389–394.

5 Fonagy P. Towards a developmental understanding of violence. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;183:190–192.

6 Rutter M., Pickles A., Murray R., et al. Testing hypotheses on specific environmental causal effects on behaviour. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:291–324.

9 Brennan P.A., Grekin E.R., Vanman E.J. Major mental disorders and crime in the community. In: Hodgins S., ed. Violence Among the Mentally Ill. Dordrecht: Kluver Academic Publishers, 2000.

10 Arsenault L., Caspi A., Moffitt T.E., et al. Mental disorders and violence in a total birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:979–986.

11 Munro E., Rumgay J. Role of risk assessment in reducing homicides by people with mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;2:116–120.

12 Simpson A.I., Allnut S., Chaplow D. Inquiries into homicides and serious violence perpetrated by psychiatric patients in New Zealand: need for consistency of method and result analysis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;35:364–369.

13 Kumar S., Simpson A.I. Application of risk assessment for violence methods to general adult psychiatry: a selected literature review. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39:328–335.

14 Turner T. Forensic psychiatry and general psychiatry: re-examining the relationship. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2008;32:2–6.

15 Roth JA 1994 Psychoactive Substance and Violence. Online. Available: www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/GovPubs/PSYCVIOL.HTM (accessed 30 Nov 2009).

16 Norko M., Baranoski M.V. In review, the state of contemporary risk assessment research. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;50:18–26.

17 MacArthur Foundation 2001 The MacArthur violence risk assessment study executive summary. Online. Available: www.macarthur.virginia.edu/risk.html (accessed 11 Aug 2002).

18 MacArthur Foundation, above, n 17.

19 Murdoch D., Pihl R.O., Ross D. Alcohol and crimes of violence: present issues. International Journal of the Addictions. 1990;25:1065–1081.

21 MacArthur Foundation, above, n 17.

22 Joyal C., Dubreucq J.-L., Grendon C., Millaud F. Major mental disorders and violence: a critical update. Curr Psychiatry Review. 2007;3:33–50.

23 Swanson J., Van Dorn R., Swartz M., Smith A., Elbogen E., Monahan J. Alternative pathways to violence in persons with schizophrenia: the role of childhood antisocial behaviour problems. Law Hum Behav. 2008;32:228–240.

24 Swanson et al, above, n 23.

25 Link B.G., Andrews H., Cullen F.T. The violent and illegal behaviour of mental patients reconsidered. American Sociological Review. 1992;57:275–292.

26 Fazel S., Langstrom N., Hjern A., Grann M., Lichtenstein P. Schizophrenia, substance abuse, and violent crime. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301(19):2016–2023.

27 Hodgins S., Tiihonen J., Ross D. The consequences of conduct disorder for males to develop schizophrenia: Associations with criminality, aggressive behaviour, substance use and psychiatric services. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;78:323–335.

28 Swanson et al, above, n 23.

29 Shaw J., Hunt I.M., Flynn S., Meehan J., Robinson J., Bickley H., Parsons R., McCann K., Burns J., Amos T., Kapur N., Appleby L. Rates of mental disorder in people convicted of homicide: a national clinical survey. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;188:143–147.

30 Scott C.L., Resnick P.J. Violence risk assessment in persons with mental illness. Aggression and Violent Behaviour. 2006;11:598–611.

32 Monahan J., Henry J., Applebaum P.S., Robbins P.C., Mulvey E.P., Silver E.A,., et al. Developing a clinically useful actuarial tool for assessing violence risk. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;176:312–319.

33 Monahan et al, above, n 32.

34 Cheung P., Schweitzer I., Crowley K., Tuckwell V. Violence and schizophrenia: role of hallucinations and delusions. Schizophrenia Research. 1997;26:181–190.

35 MacArthur Foundation, above, n 17.

36 Buckley P.F., Hrouda D.R., Friedman L., Noffsinger S.G., Resnick P.J., Camlin-Shinger K. Insight and its relationship to violent behaviour in patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1712–17114.

37 Maden A. Risk assessment in psychiatry. British Journal Hospital Medicine. 1996;56:78–82.

38 MacArthur Foundation, above, n 17.

39 Hare R.D. Manual for the Hare Psychopathy Checklist, (2nd edn, revised). Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 2003.

40 Ogloff J.R.P. Psychopathy/antisocial personality disorder conundrum. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;40:519–528.

41 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV TR). American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

42 World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases (ICD 10). Geneva: World Health Organization; 1990.

43 Cunningham M.P., Reidy T.J. Antisocial PD and psychopathy: diagnostic dilemmas in classifying patterns of antisocial behaviour in sentencing evaluations. Behavioural Sciences and the Law. 1998;16:333–351.

45 Nicholls T.L., Ogloff J.R.P., Douglas K.S. Assessing risk for violence among male and female civil psychiatric patients: the HCR-20, PCL: SV, and McNeil and Binder’s screening measure. Behavioural Sciences and the Law. 22:, 2004. 127–58.

46 Ogloff J.R.P., Davis M.R. Assessing risk for violence in the Australian context. In: Chapel D., Wilson P. Crime and Justice in the New Millennium. Sydney: Lexis Nexis; 2005:301–338.

48 Williamson F., Hare R.D., Wong S. Violence: Criminal psychopaths and their victims. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 1987;19:454–462.

49 Meloy J.R. The prediction of violence in outpatient psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1987;41:38–45.

50 Scott and Resnick, above, n 30.

52 American Psychiatric Association, above, n 41.

53 Krakowski M., Volavka J., Brizer D. Psychopathology and violence: a review of literature. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1986;27:131–148.

54 Douglas K.S., Skeem J.L. Violence risk assessment. Getting specific about being dynamic. Psychology, Public Policy and Law. 2005;11(3):347–383.

55 Norko and Baranoski, above, n 16.

56 McNeil D.E., Gregory A.L., Lam J.N., Binder R.L., Sullivan G.R. Utility of decision support tools for assessing acute risk of violence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:945–953.

57 Watts D., Bindman J., Slade M., Holloway F., Rosen A., Thornicroft G. Clinical assessment of risk decision support (CARDS): the development and evaluation of a feasible violence risk assessment for routine psychiatric practice. Journal of Mental Health. 2004;13(6):569–581.

58 Monahan J., Steadman H.J., Silver E.A., Applebaum P.S. Rethinking Risk Assessment: the MacArthur Study of Mental Disorder and Violence. New York: Oxford Press, 2001.

59 Higgins N., Watts D., Bindman J., Slade M., Thornicroft G. Assessing violence risk in general adult psychiatry. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2005;29:131–133.

60 Borum R., Swartz M., Swanson J. Assessing and managing violence risk in clinical practice. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioural Health. 1996;4:205–215.

61 Kumar and Simpson, above, n 13.

62 Litwack T.R. Actuarial versus clinical assessment of dangerousness. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2001;7:409–443.

64 Ogloff J.R.P., Daffern M. The Assessment of Inpatient Aggression at the Thomas Embling Hospital: Towards the Dynamic Appraisal of Inpatient Aggression. Forensicare, Victorian Institute of Forensic Mental Health Fourth Annual Research Report to Council; 2003. 1 July 2002–30 June 2003