Chapter 12 Risk management

Psychiatric risks (chiefly violence to self or other) are manifestations of suffering, and addressing the suffering is the primary way psychiatrists and other mental health care workers should address risk.1

Much medical effort goes into managing the risks of complications of disease processes rather than managing the symptoms of the disease itself. Hypertension is the classic example, with no symptoms but plenty of treatments, all aiming to reduce the risk of complications such as strokes and myocardial infarctions. Psychiatry’s misfortune has been to choose diseases where the complications … are homicide, suicide or reduced capacity for self-care and vulnerability.2

Risk management on its own is meaningless. It is only when it is incorporated into the treatment of the patient’s illness with a focus on recovery that it develops meaning. Before considering anything else, consider the illness. Sometimes in mental health there is no choice but to live with high risk whilst instituting appropriate treatment for the illness. This is no different to any branch of medicine. A pitfall in risk management for clinicians is instituting containment to reduce the risk which does not necessarily improve the outcome for the illness and which may also generate other risks.

The clinician does not need to predict behaviour in the next 5 years or even 6 months, but only until the next outpatient appointment or home visit by the community psychiatric nurse.3

• calculated risk-taking when the level of risk will remain high

• situations in which staff anxiety will remain high

• situations in which it may be contraindicated to reduce the level of risk

• situations in which the proposed management is counterintuitive.

EXAMPLE

The classical situation in which these bullet points arise is when a management plan for a patient with chronic suicidality is first implemented. The plan will often encourage a focus of the patient taking more responsibility for themself whilst continuing to get support from the mental health service. If the self-harming behaviour (e.g. cutting) has been reinforced by frequent long admissions to hospital or by extra phone calls, the shift of focus may cause an escalation of self-harming behaviour in the short term. This should be anticipated and discussed with the patient who will be encouraged to utilise distress tolerance techniques that they will have been learning within their individual and/or group therapy. Nonetheless, there is a real risk of cutting becoming deeper, the patient feeling rejected, and the family being more concerned. The intuitive response is to not create more distress for the patient, which in the short term would help but in the long term would be negligent. Clinician anxiety during these times is often high. (See also the example of Sally, page 115.)

Risk management can be separated into two parts: management of the risk in the here and now and planning for the future. In practice, the two parts tend not to be divided as the management of the current situation should also be future oriented. A risk management plan can be used as a ‘decision support tool’4 both in the acute situation to facilitate immediate intervention as well as for implementing interventions over a longer period.

The tasks of risk management (after the assessment is complete)

1. Decide which treatment option to take and which risk(s) should be managed.

2. Managing risk factors in the context of illness.

3. Managing any other contextual matters.

4. Managing the potential consequences (risk mitigation).

5. Communicate the plan to the patient, other clinicians involved and others involved in the patient’s care.

1 Treatment options and risk

This will occur after the assessment and may involve the risk/benefit analysis (see Chapter 10).

2 Managing the risk factors (specific strategies)

Once the decision has been made to follow a particular course of action, and the risk/benefit analysis has been documented, the management of the risk factors can be considered. This is no different to routine clinical practice.

The management of both the static and the dynamic risk factors is one which is discussed amongst the treatment team, the patient and family. The focus of trying to reduce the likelihood of the event occurring will invariably focus more on the dynamic factors as the static factors will not change. There is no rank order for predictors. The only change which may occur with the static factors is the patient’s adaptation to them. ‘The value for the clinician is in the interaction of the factors.’5

This step is usually indistinguishable from good clinical management of the disease process. As well as treating and managing risk factors, assessment and interventions for the early warning signs (EWS), triggers and relapse indicators should be undertaken. The aim of looking forward is to anticipate repetition of the context.6 This is the stage when the patterns which were identified as making the risk behaviour more likely are managed. This step is the central task of risk management.

Identification of early warning signs (EWS)

Example 1

Chris is a patient with bipolar affective disorder. He usually presents with episodes of mania but has had two episodes of major depressive disorder. He enjoys the early stages of his manic episodes as he has more energy, feels invulnerable and has lots of creative ideas which he would like to incorporate into his business. Because these ideas have not been thought through, when he has implemented them, the business has often lost large amounts of money. Most of his admissions for mania have occurred several weeks into a relapse and have necessitated involuntary admission. His wife notices the early warning signs of a relapse long before Chris does. She notices that he does not sleep well, that he becomes sexually demanding and that he takes a greater interest in fitness than is usually the case for him.

Summary of specific strategies

Consideration will need to be given to the threshold for and imminence of the risk behaviour occurring. The concepts of signature risk signs (page 20), critical risk factors (page 20) and risk scenarios (page 34) will help in this regard. For example, if an impulsive patient has a history of being violent with little obvious provocation, violence may always be close by. For other patients, it may take immense provocation for them to become violent.

A risk management plan will always complement and be a component of a fuller clinical treatment/management plan. The risk documentation should be placed in the patient’s file in such a way that it is easily accessible for all clinicians and written in such a way so that the risk factors, early warning signs and relapse indicators can be cross-checked against the patient’s mental state and external circumstances on the day that they are seen. Working with the patient and their family so that they all have copies of the risk and treatment plans makes this easier. This will also go a long way to increasing the likelihood of the management plan being feasible, the patient having better support and being less likely to be exposed to destabilising influences. These latter three factors rate highly in the Historical/Clinical/Risk Management 20-item (HCR 20) scale7 risk management part of its scale as being of importance in preventing future episodes of violence.

Consideration should always be given to strengthening the protective factors. This is now being explored in one standardised rating scale.8

4 Managing the potential consequences (risk mitigation)

Are the following questions able to be answered?

• Does the patient/family/company perceive the risk in the same way as the clinicians? Discrepancies in the perception of the risk by different people will cause substantial problems in the implementation of a risk management plan.

• How much responsibility can the patient or their family take at this time?

• Who is taking responsibility for the risk? Is it the clinician, the patient, the family? Is the responsibility shared? Does the family know the likelihood of death, suicide, assault, etc?

• Does the patient/family support the clinical approach? Patients and families are less accepting of risks over which they have little or no control, or where the consequences are dreaded. Patients and families are less likely to accept risks if there are no perceived benefits.

• Do senior clinicians support the approach? They will be the support if there is an adverse outcome. Do they even know what treatment approach is being followed? Do they need to know?

• Is there agreement from all on the level of risk?

• Will the management of the risk distract from, derail or complement the treatment of the illness?

• Has management of other risks been included; for example, media exposure?

• Consider: is a minor risk being managed because the major ones seem too hard to deal with?

5 Communicate to all concerned

Duty to warn and protect: a dilemma in communication

The duty to warn and protect is a relatively new concept and is a departure from traditional psychiatric practice. This so-called duty is to a large degree defined by legislation and case law.9

… when a therapist determines, or pursuant to the standards of his profession should determine, that his patient presents a serious danger of violence to another, he incurs an obligation to use reasonable care to protect the intended victim against such danger. The discharge of this duty may require the therapist to take one or more various steps depending on the nature of the case. Thus, it may call for him to warn the intended victim or if it is likely, to appraise the victim of a danger, to notify the police, or take whatever steps are reasonably necessary under the circumstances.10

The onus on the mental health worker is to make him or herself aware of the current legal obligations with respect to duty to warn and protect. It is likely that this evolving area of law will continue to have a substantial impact on the care of the mentally ill.

There are some general guidelines that apply to most situations.

• A full risk assessment should be undertaken before any action is taken.

• The phrase ‘if the release of that information is necessary to prevent or lessen a serious or imminent risk to others’ should be considered as the litmus test for consideration of a breach of confidentiality.

• The clinical conundrum of differentiating between fantasy which needs to be discussed within the context of treatment and the reality of a threat of violence is a difficult area. It is likely that there is a continuum between fantasies of violence and direct threats.

• Laws about breaching confidentiality are slightly different in each country and, if uncertain, advice should be taken from a senior colleague or the legal services of the workplace.

• The person or group at risk needs to be identifiable.

• If usual clinical interventions such as admitting the patient to hospital cannot control the risk, it may be necessary to inform the third-party without the patient’s consent in order to manage the risk. Only enough information to protect the third party should be disclosed. It would be rare that disclosure of psychiatric information would be required.

• Information may be passed on to an authority (e.g. the police) to protect the person at risk. If appropriate, the patient should be told that you are going to do this. If the patient’s condition will worsen as a result, the patient should be told at a later time.

• This is a rare situation and the advice of senior colleagues should always be taken whenever possible.

6 Documentation of risk management

The level of risk is usually closely linked to acuity of illness. It is usually raised when a patient experiences deterioration of mental state or when situational factors re-occur. On the risk plan there should be spaces for documentation of risk factors, early warning signs and triggers along with recommendations for interventions should these occur in the acute situation. Although interventions may have been implemented to reduce the risk in the long term, crises can still occur. The risk management plan should include recommended interventions for these situations. The proposed interventions can only ever be recommendations. The final decision has to be left to the clinician on the spot because of the many variables which will need to be factored into each unique situation.

Where possible, the patient should have a copy of their risk and treatment plans.

Example

In 1999 in Ballarat, Australia, a young woman committed suicide some months after discharge from hospital. She had a long history of substantial self-harming behaviour and a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD). The discharge planning from hospital had involved close consultation with the patient, her family and the wider system involved in her care. Everybody involved knew that there were substantial risks but it was also clear that prolonged inpatient hospitalisation was not improving matters. At the inquest, the coroner was able to review the extensive documentation and communication which occurred. His words were:

‘I do not blame or criticise anyone for what has happened. It has been an extremely difficult situation. Grampians Psychiatric Services, Centacare and Ballarat Psychiatric Fellowship gave her everything and made a commitment to support her in every way possible. I only have praise for them.’13

Even when the outcome is adverse, clinicians do not need to be blamed.

7 Implement the plan in context of the treatment

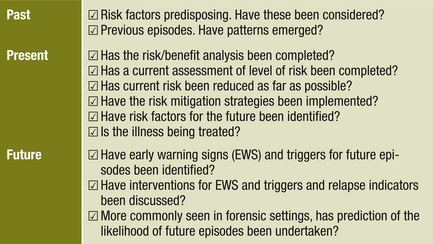

Before implementing the plan, check that the future has been considered with reference to the past and present. Table 12.1 has a check list to work through.

Table 12.1 Past, present and future checklist

8 Review and evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention

BOX 12.1 RISK MANAGEMENT

• A risk management plan should be placed in the patient’s file in such a way that it is easily accessible for all clinicians.

• Managing the illness usually reduces risk.

• Imminence of risk is assessed at each meeting with the patient.

• Consider any contextual factors which may be of immediate relevance; for example, time of day, geographical situation, whether family are present, etc.

• Treatment of risk factors combined with assessment and intervention for the EWS, triggers and relapse indicators is the usual practice for reducing the likelihood of the risk behaviour occurring.

• A risk management plan will always complement and be a component of a fuller treatment/management plan.

• Consider the truism, ‘If it wasn’t documented, it didn’t happen’.14

• The treatment plan should include interventions for all the identified dynamic risk factors.

The next two exercises in this section focus on the identification of interventions for the risk factors, early warning signs and triggers. The interventions are likely to be utilised in the treatment plan even if they are generated initially through the pathway of risk management. As described previously, the ability to ‘cut and paste’ makes the process of moving interventions from risk management plans to treatment plans easy. In the exercises, the plans have been partially completed. There is new information for both Colin and Monique and all that is required is for the early warning signs, triggers and interventions to be written in. Be creative with your answers and imagine that you are working alongside your patients whilst you are completing the exercises. The final part of the risk management form is a review of the efficacy of the interventions. Make sure you add a review date. This should be planned after determining how frequently the patient needs to be monitored.

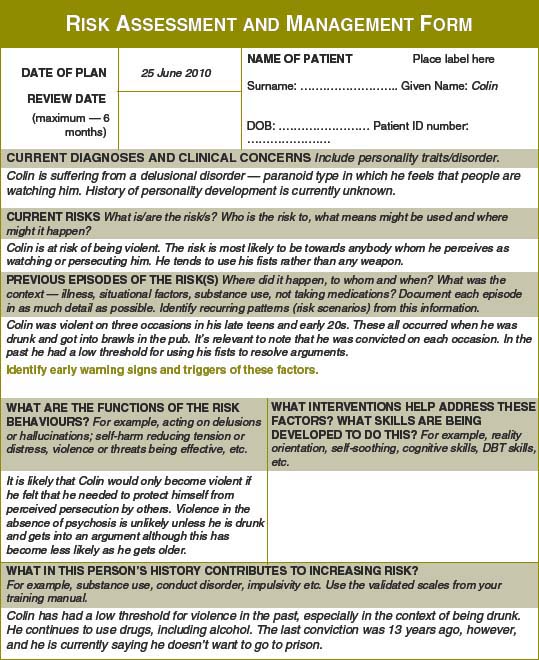

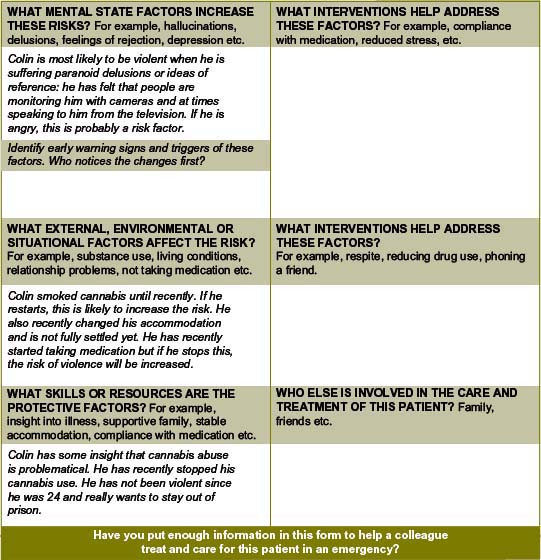

Exercise 1 — Colin (continued)

You will remember Colin from Chapter 9 (exercises 3 and 6) and Chapter 10 (exercise 1).

The original example appears below, along with some new information.

These thoughts went on for some time and became more problematical for him. His girlfriend thought he was going crazy and left. In the end, Colin decided to leave his flat and moved to your town to start afresh. He has no family support in your town and finds himself wandering the streets where he recites prayers to try and distract himself from thinking that people are talking about him. Approximately 1 month ago, Colin noticed that when he smoked more cannabis, the ‘paranoid’ ideas became stronger and he wondered if the cannabis was the problem. He has used speed (methamphetamine) occasionally. He decided to stop the cannabis and, over the last few weeks, the paranoia has settled slightly, but it has certainly not gone away. Colin has found himself wondering if people on the streets are talking about him and has also wondered if his new flat mate is watching him. Colin has past convictions for assault; when he was 19 years old and again at 21 and 24. He tells you that he has learned to control himself since that time and wouldn’t hurt anybody now. These assaults occurred in the context of brawls, which he got into when he was drunk. He says he normally wouldn’t hurt a fly.

New information

Parts of the risk management plan (Figure 12.1) have been completed for you. Fill out some EWS, triggers and relapse indicators for the risk management plan. Use your clinical judgment to think of some interventions which may help. Add in a date for when you think the plan should be reviewed.

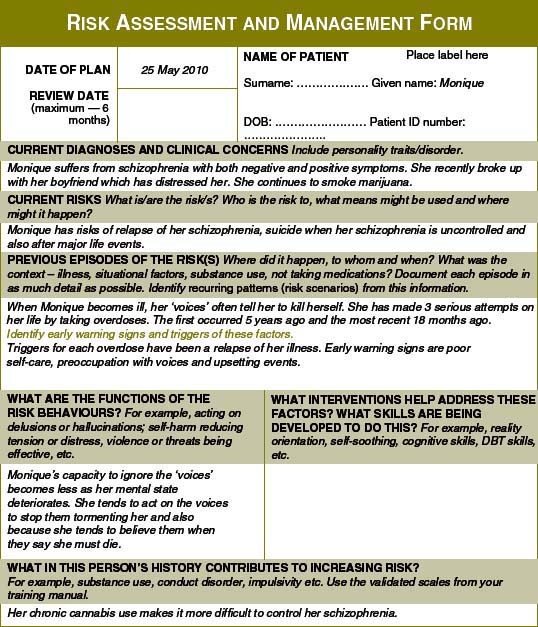

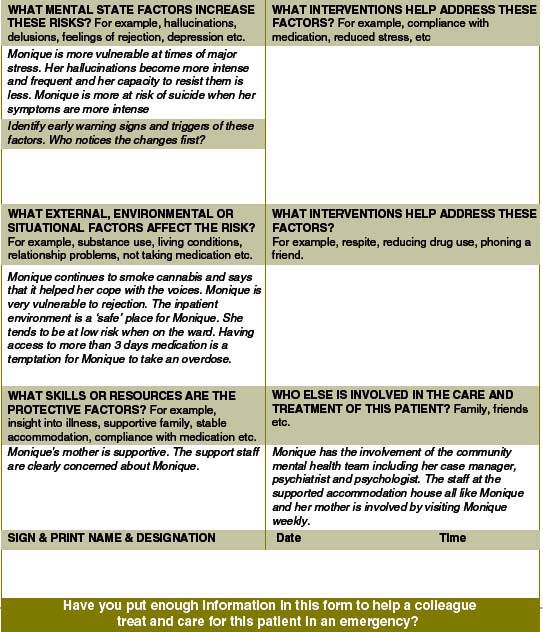

Exercise 2 — Monique (continued)

You will remember Monique from Chapter 9 (exercises 1 and 5). The original example appears below, along with some new information.

Monique’s illness is characterised by both positive and negative symptoms. She continues to have auditory hallucinations which comment on her actions and occasionally put her down. Sometimes her voices tell her to hurt herself. Her self-care has deteriorated over the last few years, she has lost some of her outgoing vivaciousness and she has fewer friends. She continues to smoke cannabis from time to time. Six years ago, she became pregnant and had a termination. One year later, she became pregnant again and the baby was adopted out. She now uses a depot injection for contraception.

Monique was in a relationship with another resident at the hostel.

New information

Parts of the risk management plan (Figure 12.2) have been completed for you. Fill out some EWS, triggers and relapse indicators for the risk management plan. Use your clinical judgment to think of some interventions which may help. Add in a date for when you think the plan should be reviewed.

Comment

The immediate precipitants for Monique’s current difficulties were the breakdown of the relationship with her boyfriend. The documentation in the risk management plan has not identified the importance of giving Monique some assistance and support to help her come to terms with the end of this relationship. Without this, it is likely that the risk of suicide will remain for some time. This is perhaps an example of the focus on risk overriding the need to help the patient manage the real problem, which in this case is the distressing end of a relationship.

1 Undrill G. The risks of risk assessment. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2007;13:291–297.

2 Maden A. Violence risk assessment: the question is not whether but how. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2005;29:121–122.

3 Maden A. Risk assessment in psychiatry. British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 56, 1996. No2/3.

4 McNeil D., Gregory A.L., Lam J.N., Binder R.L., Sullivan G.R. Utility of decision support tools for assessing acute risk of violence. Journal Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:945–953.

5 Maden A. Treating Violence: a Guide to Risk Management in Mental Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

6 Grounds A. Risk assessment and management in clinical context. In: Crichton J., ed. Psychiatric Patient Violence: Risk and Response. London: Duckworth; 1995:43–59.

7 Webster C.D., Douglas K.F., Eaves D., et al. HCR-20: Assessing risk of violence (version 2). Vancouver: Mental Health Law and Policy Institute, Simon Fraser University; 1997.

8 Webster C.D., Nicholls T.L., Martin M.L., Desmarais S.L., Brink J. Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START): The case for a New Structured Professional Judgment Scheme. Behavioural Science and the Law. 2006;24:747–766.

9 Chaimowitz G.A., Glancy G.D., Blackburn J. The duty to warn and protect — impact on practice. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;45:899–904.

10 Applebaum P.S., Gutheil T.G. Clinical Handbook of Psychiatry and the Law, 2nd edn, Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1991.

11 Gellerman D.M., Suddath R. Violent fantasy, dangerousness, and the duty to warn and protect. The Journal of the American of Psychiatry and the Law. 2005;33:484–495.

12 Gutheil T.G. Paranoia and progress notes: a guide to forensically informed psychiatric record keeping. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1980;31(7):479–482.