Chapter 3 Risk factors and risk equations

Risk factors1

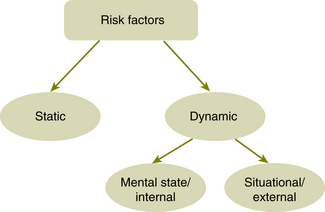

Risk factors can be divided into two main categories:

1. static factors (also referred to as enduring, stable or historic factors)

2. dynamic factors (also referred to as current or variable factors).

A comprehensive analysis of static risk factors can help ensure that clinicians take account of historical material and consider pre-existing vulnerabilities for (violence) risk when planning long-term treatment strategies.2

Some examples of static factors include:

• For violence: previous episodes of violence, conduct disorder and alcohol and drug history.

• For suicide: previous attempts, family history of suicide, history of mental illness.

Lists of risk factors for violence and suicide can be found in Chapter 9 (Tables 9.1 and 9.2, pp 80, 84).

The static factors set the context in which a clinician works.3 Empirically it makes sense that the closer the patient is to these factors in time, the greater the influence they will have. However there is currently no literature available to support this. An extreme example would be of a man who was repeatedly violent in his youth but is now presenting at the age of 75. The weighting given to these factors is likely to be less than had he presented at the age of 25.

Dynamic risk factors are those factors which are more likely to change:

• as a result of alterations in the patient’s mental state such as a lowering of mood (internal) and/or

• changes in the patient’s external environment (situational) such as the dissolution of a relationship or loss of job.

Dynamic factors capture the fluctuating nature of risk. Dynamic factors may change in both duration and intensity. A single event may cause changes to a number of dynamic risk factors creating a change to the overall risk. Assessing the dynamic factors is essential for considering the particular conditions, patterns and circumstances that place individuals at special risk. Hanson and Harris (2000)4 distinguished between stable and acute dynamic factors. Stable dynamic factors (e.g. traits of impulsivity or hostility) are unlikely to change over short periods of time, but can change gradually. In contrast, acute dynamic factors (e.g. drug use and mental state) can change daily or even hourly.

It is not sufficient to consider risk factors in isolation and manage them individually. Risk factors can affect each other in various ways. For example, one risk factor may moderate the effect of another or a second risk factor may only become relevant if the first risk factor is present. There are many possible permutations which will need to be formulated by clinicians for each patient. Whenever there are more than two causal risk factors these issues must be considered.5 (A causal risk

BOX 3.1 THE NATURE OF RISK

• Risk in a mental health setting is never static.

• The likelihood of the risk behaviour occurring is often linked to the severity of the illness.

• The nature of a patient’s risk doesn’t usually change; it is the likelihood and context which changes.

• The likelihood of the risk changes most with changes of the dynamic factors.

• Given the fluctuation of dynamic risk factors in patients, measures of the level of risk may have little value other than stating what it was on that particular day.

• If there is a heavy weighting of static risk factors, this is worth highlighting as the tipping point into the risk behaviour may be reached quickly.

factor is one that can be changed by manipulation and when changed can be shown to alter the risk.)

In some persons with mental or personality disorder and a history of violence or self-harm, a highly specific, ‘signature’ set of patterns or signs may be identified (e.g. a preoccupation with certain people, or a change to a behaviour pattern), as a ‘calling card’ for their mental illness and the potential risk for violence to self or others.6

These personal signature risk signs and patterns of behaviour can be useful concepts for clinicians to consider when assessing patients. The concept of ‘signature risk signs’ has been incorporated into the thinking behind ‘START’, an assessment tool currently being evaluated.7 Along similar lines, the concept of ‘critical risk factors’ is also worth considering. These are 2–3 risk factors which will be of great importance for specific individuals and can be highlighted in management plans as flags for rapid intervention.

Looked at diagrammatically, risk factors can be presented as shown in Figure 3.1.8

When it comes to documenting the risk, this diagram can be referred to. The risk documentation framework used in the book is to a large degree based on this model.

Example 1 — violence risk factors

The synthesis of the static and dynamic risk factors combines to give the current ‘risk state’.9, 10 The risk state is a term used in some literature to describe the likelihood of the risk occurring at a given time.

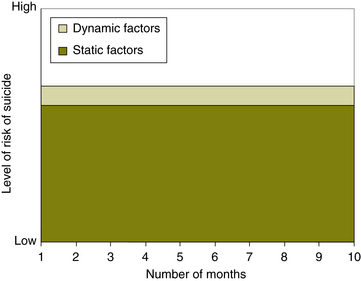

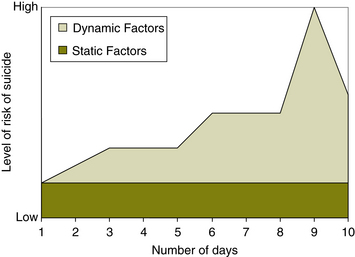

The graphs in Figures 3.2 and 3.3 help describe the idea of risk being a synthesis of static and dynamic factors. The second graph also shows how the likelihood of the risk occurring can change quickly.

Example 211

Figure 3.2 shows graphically a patient with chronic depression. The patient is a 54-year-old woman who has had recurring episodes of major depression throughout her adult life. Treatment has included antidepressants, supportive psychotherapy and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). On three occasions she has attempted to kill herself. On the last occasion she was found accidentally by a hunter as she was gassing herself in her car, which was parked deep in the woods. She has a lot of static risk factors: three previous suicide attempts, physical illness, sexual abuse as a child, family history of mental disorder and her own history of mental illness. These leave her especially vulnerable to the risk of relapse and further suicidality if there is a small change in her dynamic factors. This needs to be considered when assessing and managing the risk.

Precipitating events can ‘tip the balance’12 easily into a risk event and may only need to be minor in this example. It may be necessary to review the patient frequently as it will only take a small change in the dynamic factors for the pathway into suicide to be completed. Being mindful of the weighting given to each of the static and dynamic factors is going to be important in the assessment of what it takes for a patient’s suicidal intent to be realised. For individual patients, there are likely to be specific releasing factors (signature risk signs) clustered into two or three critical risk factors that tip the patient over into the risk behaviour.

Example 3

Figure 3.3 shows a very different scenario. This patient is a young man of 25 who is ‘happily married’. He has no previous history of mental illness but does drink in a binge pattern. Over the course of 10 days, he loses his job on day 1, his father has a heart attack on day 5 and his wife confesses she has been having an affair with his brother on day 8! This patient has very few static factors for suicide which would usually pose little risk but over the period of a few days, he has a series of life events which destabilise his mental state and raise the risk of suicide substantially. He has dynamic risk factors of loss, recent adverse events, rage and feeling abandoned. On day 9 the risk peaks and by day 10 there has been some resolution of the dynamic factors and the risk rapidly reduces. In Chapter 9 there is a list of risk factors for suicide (Table 9.1, p 80) which will help when doing assessments.

Thus the word ‘likelihood’ in the equation

Although the nature of the risk (e.g. in this case violence) is unlikely to change, the likelihood can change enormously. When assessing risk, it is a little bit like making a diagnosis: a diagnosis is only a snapshot in time. A risk assessment is similarly a snapshot in time and its predictive quality weakens with every passing hour and day. A risk assessment will give the indicators and patterns of what makes the risk behaviour more likely to occur. Risk management involves an assessment of the current circumstances whenever the patient is seen. This includes a review of the patient’s mental state and the patient’s external environment; that is, no different to routine and usual clinical practice.

Level of risk

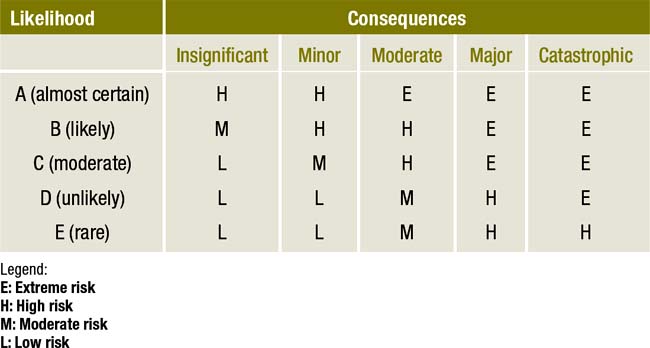

Table 3.1 demonstrates the changeability of the level of risk with fluctuations of likelihood and consequences.

High, moderate or low risk?

Describing a patient as high risk may not be conducive to developing a therapeutic alliance as there will be a tendency to be rejecting of patients. Compliance with treatment will be less likely. The stigma attached to patients if they are categorised as being high risk should be avoided where possible. Another argument to be made against using a focus on level of risk is that resources may be diverted towards those deemed to be at highest risk and away from those with other mental illnesses.13

Risk assessment and management plans should be explicit about the time period for which they are made. To set a valid schedule for assessing and monitoring risk state, a clinician must have a sense for the speed at which an individual’s most important dynamic factors will change.14

Using standardised tools such as the Historical/Clinical/Risk Management 20-item (HCR 20)15 help identify the level of risk but will not necessarily add anything to the meaning of the risk behaviour for the patient, which will be specific to them.

If the interests of the patient are given primacy, there is little problem. However, violence risk assessment processes may be utilised with public protection as the primary goal. This is ethically troubling territory for the mental health professional, even more so where the processes rely entirely on static risk factors that are not open to therapeutic change.16

Summary

• Levels of risk can be useful in setting up systems for regular monitoring of patients.

• Levels of risk need to be clearly defined for each risk group and possibly for different settings in order to be meaningful.

• Levels of risk can identify patients from whom the public needs to be protected. (Some people suggest that this is using risk management to be an agent of social control.)

• Using levels of risk can help identify patients who need greater numbers of resources. The risk here is that other patients miss out.

• Documentation of level of risk may cause stigma to the patient.

Exercise — level of risk changing over time

Two days later, Richard is an inpatient in the psychiatric unit. He is beginning to question whether his family would be better off without him.

Refer to Appendix 3 for possible answers.

BOX 3.6 PRACTICE TIPS

• A narrative approach indicating in which situations a patient may be at higher or lower risk is useful. It allows for identification of times of increased risk and for interventions to be planned.

• If the risk is documented as high, moderate or low, frequency and levels of monitoring need to be specified and review dates included. To set a valid schedule for assessing and monitoring risk state, a clinician must have a sense for the speed at which an individual’s most important dynamic factors will change.

• The decision whether to document level of risk may be made for you by your managers. If not, think carefully about the clinical usefulness of documenting a level of risk at this time and whether it will help your patient. It is always useful to ask the question ‘Is the risk being rated as high for the benefit of the patient or the protection of the public?’

1 Bouch J., Marshall J.J. Suicide Risk: structured professional judgment. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2005;11:84–91.

2 Mullen P. Dangerousness, risk and the prediction of probability. In: Gelder M., Lopez-Ibor J.J., Andreasen N.C. New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000:2066–2078.

3 Maden A. Treating Violence: a guide to risk management in mental health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

4 Hanson R.K., Harris A.J.R. Where should we intervene? Dynamic predictors of sexual offense recidivism. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2000;27:6–35.

5 Kraemer H.C. Current concepts of risk in psychiatric disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2003;16(4):421–430.

6 Fluttert F. Nursing study of personal based ‘early recognition and early intervention’ schemes in forensic care. Melbourne: Paper presented at 5th Annual Conference, International Association of Forensic Mental Health Services; 2005. April.

7 Webster C.D., Nicholls T.L., Martin M.L., Desmarais S.L., Brink J. Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START): The case for a New Structured Professional Judgment Scheme. Behavioural Science and the Law. 2006;24:747–766.

8 Adapted from: New Zealand Ministry of Health 2006 Assessment and Management of Risk to Others Guidelines; Development of Training Toolkit; and Trainee Workbook. New Zealand Ministry of Health. Online. Available: www.mhwd.govt.nz (accessed 12 Oct 2009).

9 Skeem J.L., Mulvey E. Monitoring the violence potential of mentally disordered offenders being treated in the community. In: Buchanan A., ed. Care of the Mentally Disordered Offender in the Community. New York: Oxford Press; 2002:111–142.

10 Douglas K.S., Skeem J.L. Violence risk assessment. Getting specific about being dynamic. Psychology, Public Policy and Law. 2005;11(3):347–383.

11 Adapted from Bouch J., Marshall J.J. Suicide risk: structured professional judgment. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2005;11:84–91.

12 New Zealand Ministry of Health. Guidelines for Clinical Risk Assessment and Management in Mental Health Services. New Zealand Ministry of Health, 1998. p 17.

13 Szmukler G. Risk Assessment: ‘numbers’ and values. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2003;27:205–207.

14 Douglas & Skeem, above, n 10.

15 Webster C.D., Douglas K.F., Eaves D., et al. HCR-20: Assessing Risk of Violence (version 2). Vancouver: Mental Health Law and Policy Institute, Simon Fraser University; 1997.

16 Carroll A. Are violence risk assessment tools clinically useful? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41:301–307.

17 Undrill G. The risks of risk assessment. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2007;13:291–297.