Chapter 11 Risk assessment: focus on documentation

Documenting the risk

The importance of documenting risk cannot be understated. From a medico-legal perspective, ‘if you didn’t write it, it didn’t happen’.1 In situations where there is risk, a certain amount of trial and error, uncertainty and so forth, ‘thinking out loud for the record’2 is a useful reminder. Documenting the risk also provides a framework for thought. It has been difficult to develop any one process which successfully incorporates everything to do with risk management into the routine clinical file. There are, however, a few principles of risk management which cannot be ignored. The findings from international inquiries state consistently that the most common failings are those of poor documentation and poor communication.3 There is a medico-legal requirement to document well and clinicians put themselves and their patients at substantial risk when this doesn’t happen.

Documentation of risk should be concise but contain enough detail as to be useful to a clinician unfamiliar with the patient; for example, those seeing the patient out of hours. The documentation should be useful and not something which is put in the ‘file and forget’ basket. As the document will also be shared with the patient, language the patient can understand should be used (i.e. without psychiatric terminology).

• risk assessments, no matter how brief, are copied onto a risk form and put into a separate compartment in the file

• risk documentation is written on different coloured paper

• all risk documentation is copied to the mental health crisis team

• as more information becomes available, this should be added to the risk plan incrementally

• if risk issues are incorporated into the assessment, these are given headings and put in a box.

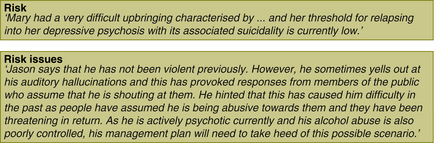

See Figure 11.1 for examples.

Where mental health services have moved to electronic health records (EHR), this process becomes much easier as risk documentation can automatically be incorporated into the relevant areas of the EHR. Subheading boxes within the risk plan can be completed directly from the assessment. Similarly, subheadings from the risk plan — especially identification of early warning signs and triggers — can be pasted directly into the treatment plan ensuring that the treatment plan covers the management of the risk factors. Updating of risk and treatment plans becomes much easier.

BOX 11.1 RISK DOCUMENTATION — THE RISK PLAN

Practice points: what a risk plan does

• It documents that risk has been considered and assessed.

• It puts the risk into the context of the current illness (mental state factors and patterns).

• It allows for consideration of situational factors (and patterns).

• It documents protective factors.

• It lays the foundation for risk management

• When combined with the treatment plan, dynamic risk factors and signs of relapse will also be managed.

• It does not usually state a definitive plan of action but makes recommendations. Treatment decisions in the acute situation are left to the clinician on the spot.

• Documenting the risk in a risk plan becomes a component of treatment for the underlying illness.

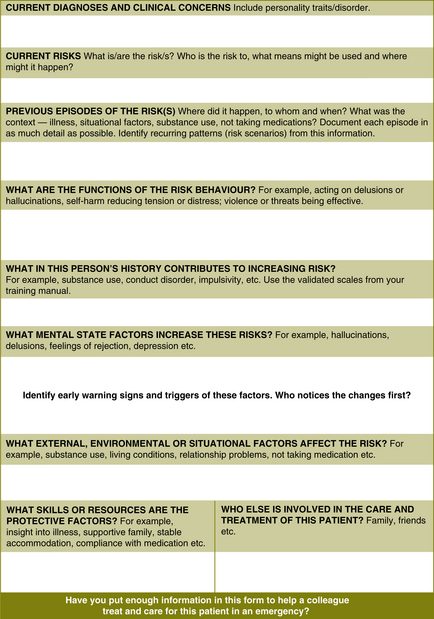

The only part missing after these exercises will be the introduction of interventions for the risk factors, early warning signs and triggers. When necessary, use the list of risk factors in Tables 9.1 and 9.2 (pages 80–81 and 84–85). Remember, it is more useful for your colleagues if you write in a narrative form but don’t get carried away by writing a thesis! The idea is to be brief and succinct. A test of the usefulness of your documentation is to show it to a colleague and ask them if it makes sense. As you get used to completing these examples, you will begin to notice that they also help you highlight areas where the treatment will need to focus. To an extent, documenting the risk in the form of a plan will direct some aspects of treatment.

Don’t worry about whether you get the information in the correct box. As long as you get the information down on paper, your colleagues will be able to make use of it. You may also find that the same information is documented twice. Once again, it’s better that it’s down on paper than not at all.

Exercise 1 — Depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

David lives on his own and has few friends. He does not wish you to talk to his friends. He says that he has not been violent in the past and he does not drink or use drugs. He says that he does not want to kill himself but wonders how long he can endure this torment. He has made no plans to kill himself. From the information given, complete the risk documentation form for David. Figure 11.2 contains a risk documentation template. The completed form appears in Appendix 3.

Comment

This example is not uncommon in routine clinical practice. The risks are of both suicide and violence and the two are interlinked. What the clinicians have not done here is explore the risks in sufficient detail. They will need to ask the patient what means he might use for suicide or violence, whether he has planned it, and what might happen if he met the teacher on the street. They will need to consider impulsivity and consider what may tip him over into a violent or suicidal act. Are there any critical risk factors and signature risk signs which may be of importance? No early warning signs and triggers have been identified yet. The clinicians will need to meet to discuss this in some detail with David. However, it is important to start documenting the risk even if more details will be forthcoming later. The process of documenting the risk on a form often highlights areas of the history and current thinking that need clarification. The documentation on motivation for the risk behaviour carries vital information for a colleague caring for David after hours.

Example 2 — child and family example

From the information given, complete the risk documentation form for Mike. Refer to Figure 11.2 for a risk documentation template. The completed form and discussion appear in Appendix 3.

Exercise 3 — an example of using the model for exploring relapse prevention

Brian is a 45-year-old man with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder. His history is of several manic episodes complicated by auditory hallucinations, grandiose delusions and persecutory ideation. Not infrequently, the psychotic symptoms continue after the mood component has settled. The auditory hallucinations are variable in their content. Sometimes they tell him he is wonderful and can do anything he wants and at other times they have a paranoid flavour to them and tell him that he is being watched.

From the information given, complete the risk documentation form for Brian. Refer to Figure 11.2 for a risk documentation template. The completed form and discussion appear in Appendix 3.

Exercise 4 — alcohol and drug example

Four months ago, Rachel had a major relapse into alcohol use and, after smashing the family car and falling down the stairs, she voluntarily admitted herself to a residential program. For the first 6 weeks of the 8-week program she participated little but in the last 2 weeks, she began to participate and acknowledged that she no longer loved her husband and that the date rape caused her to avoid sex and also gave her nightmares. Since returning from her residential treatment, Rachel has again relapsed and says that she will not go back to residential treatment again. She says that she will be able to sort things out in her counselling. She has not told her husband about her feelings about the marriage. Her liver function tests are surprisingly normal. Although you have advised her not to drive, her husband tells you that she is still driving her children to school.

From the information given, complete the risk documentation form for Rachel. Refer to Figure 11.2 for a risk documentation template. The completed form and discussion appear in Appendix 3.

BOX 11.2 CLINICAL TIP

• A general rule of thumb if a patient is intoxicated at the time of assessment is to assume that a thorough mental state examination cannot be completed until the patient is no longer under the acute influence of the drug.

• Intoxication may well mean that the patient needs to be contained in a place of safety until sober.

• Policies and memoranda of understanding should be in place between mental health services, Emergency Departments (EDs) and police to manage this common occurrence.

• Clinicians should make a point of getting a collateral history from friends and family at these times.