Chapter 22 Rigid Bronchoscopy with Laser and Stent Placement for Bronchus Intermedius Obstruction from Lung Cancer Involving the Right Main Pulmonary Artery

Case Description

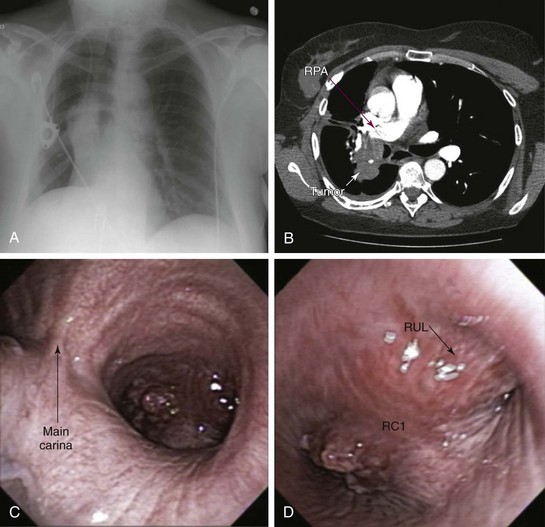

A 50-year-old female with a 30–pack-year history of smoking developed wheezing and worsening shortness of breath, limiting her daily activities. Right lateral decubitus position worsened her symptoms, and she could not sleep on her right side. She was admitted to an outside hospital, where flexible bronchoscopy showed complete obstruction of the right upper lobe bronchus and severe obstruction (≈80%) of the bronchus intermedius (BI). She was transferred for bronchoscopic restoration of airway patency. The patient had a history of stage III squamous cell carcinoma of the lung diagnosed 18 months previously. Her pulmonary function test at that time showed a vital capacity of 2.94 L (80% predicted) and FEV1 of 2.39 L (85% predicted). She received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy followed by right lower lobectomy and mediastinal node dissection; all nodes were negative. The primary tumor measured 2.5 × 2 × 2 cm and extended to the parenchymal resection margins; evidence showed peritumoral lung consolidation related to the secondary effects of radiation therapy. Shortly after undergoing treatment, the patient lost her insurance coverage and was unable to pursue clinical or imaging surveillance. Comorbidities included rheumatoid arthritis (RA) requiring methotrexate and prednisone 20 mg/day and bipolar disorder treated with valproic acid. She was unemployed and divorced and lived with her children. Her physical examination was remarkable for expiratory wheezing noted in the right lung field. No limitation of cervical spine mobility was detected, but she had ulnar deviation of her hands and swan neck deformities of her fingers. She had significant functional impairment with a KPS score of 30 and was scored ECOG 3. Chest radiography showed a prominent hilar mass and right middle lobe atelectasis (Figure 22-1, A). Chest CT revealed a mass measuring 4 × 7 × 3 cm that invaded the BI and encased the right pulmonary artery (Figure 22-1, B). Repeat flexible bronchoscopy showed a near complete mixed pattern of obstruction (by exophytic tumor and extrinsic compression) of the BI, but right middle lobe bronchial segments were patent. The right upper lobe bronchus was occluded by extrinsic compression (Figure 22-1, C and D), but the flexible bronchoscope could be passed beyond the occluded airway, noting patent anterior and apical segmental bronchi (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video V.22.1![]() ). Echocardiogram showed a systolic pulmonary artery pressure of 60 mm Hg and a moderately dilated right atrium but normal bilateral ventricular size and function.

). Echocardiogram showed a systolic pulmonary artery pressure of 60 mm Hg and a moderately dilated right atrium but normal bilateral ventricular size and function.

Discussion Points

1. Enumerate four anesthesia considerations during rigid bronchoscopic laser resection in this patient in light of severe bronchial obstruction and pulmonary artery involvement.

2. Enumerate three different types of stents that could be inserted in this patient with incomplete obstruction of the bronchus intermedius and right upper lobe bronchus.

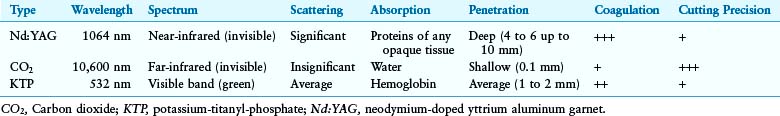

3. Explain differences in tissue penetration and coagulation effects of neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG), CO2, and potassium-titanyl-phosphate (KTP) lasers, and describe pertinent clinical implications for treating obstructive airway lesions.

4. Describe the principle of power density and its effect on tissues when the Nd:YAG laser is used.

Case Resolution

Initial Evaluations

Physical Examination, Complementary Tests, and Functional Status Assessment

This patient’s focal wheezing on auscultation of the right chest suggests airflow obstruction distal to the carina.1 Positional wheezing suggests a component of dynamic obstruction such as excessive dynamic airway collapse, malacia, or, as in our patient, positional worsening in an already narrowed airway. When localized to a bronchus, these processes will be worsened in the lateral decubitus position.

The hand-joint deformities seen in this patient are characteristic of advanced rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and may predict involvement of the axial skeleton,2 of which the cervical spine joints are the most clinically important, with a prevalence of involvement ranging from 15% to 86%.3 This patient had no symptoms of instability related to atlantoaxial (C1-C2) or subaxial (below C1-C2) subluxation. These include neck pain, stiffness, and radicular pain, all of which should be explored in cases of rigid bronchoscopy or endotracheal intubation. During these procedures, the cervical spine is hyperextended to align the mouth, larynx, and trachea. In one study, preoperative cervical spine assessment with cervical spine films in asymptomatic patients with RA before elective surgery revealed an incidence of unsuspected C1-C2 subluxation of 5.5%.4 Subluxations can vary over time, may be unrecognized, and can be fatal in up to 10% of patients because of spinal cord or brainstem compression.5 Because of the dangers of neck movements required for intubation, and because subluxation is not always symptomatic, radiographic evaluation of the cervical spine probably should be considered for all patients with RA scheduled to undergo procedures requiring cervical manipulation.6

The cricoarytenoid joint may be involved in 30% of patients with RA. Hoarseness and stridor in patients with RA suggest laryngeal involvement and are present in 75% of patients,7 but those with chronic cricoarytenoid arthritis may be relatively asymptomatic. Any disease process leading to hyperventilation, increased airflow (exertion, acidosis, infection), or reduction in the diameter of the airway (upper respiratory infection) can precipitate symptoms.8 In addition, patients with cricoarytenoid arthritis are at risk both during intubation and after extubation. Intubation may be difficult if the airway is narrow and, even if atraumatic and of short duration, can prompt mucosal edema and further compromise of airway caliber, leading to airway obstruction and stridor following extubation.9 Systemic glucocorticoids are often effective in reversing the obstruction caused by acute cricoarytenoid arthritis, and local periarticular steroid injections have been shown to improve cricoarytenoid function. In chronic cricoarytenoid arthritis, the degree of airflow limitation dictates the need for laser cordotomy or arytenoidectomy.10 Other potential manifestations of RA that could interfere with airway management include limited temporomandibular joint (TMJ) mobility (<4.5 cm), which is present in approximately 66% of patients with long-standing RA. Most of these patients experience pain and tenderness in the TMJ. Upper airway obstruction can occur because of pharyngeal obstruction, as in patients with micrognathia or obstructive sleep apnea. Furthermore, a small mouth opening from TMJ disease may preclude rigid bronchoscopic intubation. In our patient, upper airway anatomy was normal, and no signs of RA-related laryngeal involvement or TMJ disease were noted.

Comorbidities

This patient had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Although possibly attributable to higher unmeasured severity of illness in patients with psychiatric comorbidity, existing psychiatric disease has been found to be associated with a modestly increased risk of death among patients undergoing surgery.11 Our patient had been taking prednisone 20 mg/day for many years. The equivalent of 15 mg/day of prednisone for longer than 3 weeks should raise suspicion for hypothalamic-adrenal axis suppression,12 warranting increased glucocorticoid supplementation associated with possible adrenal insufficiency related to medical and surgical stress.12 In this regard, one must recall that supplemental corticosteroids can induce or exacerbate manic or depressive episodes, potentially interfering with postoperative care.13

Support System

1. Mental illness is associated with higher case-fatality rates in patients with cancer, in part because of the challenges of drug interactions, lack of capacity, and difficulties in coping with treatment regimens as a result of psychiatric symptoms. A multidisciplinary approach that includes members of mental health services is warranted to ensure effective treatment and to avoid inequalities of care that might result from physician biases or mismanagement of patient behaviors and treatment choices.14

2. Nonoperative non–small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) trials showed that marital status was not independently predictive of overall survival; however, single females had significantly better overall survival than both single and married males.15

3. Socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with NSCLC may receive less intensive cancer-specific care. Differences in access to care, comorbidities, and lifestyle may contribute to these inequalities.16

Patient Preferences and Expectations

This patient wished to improve her shortness of breath, which caused significant emotional and physical distress. Results from studies show that more than 50% of patients with inoperable lung cancer report breathing difficulty, pain, and fatigue as the symptoms most associated with physical and emotional distress.17

Procedural Strategies

Contraindications

The lack of functional lung distal to the obstruction would preclude bronchoscopic interventions. In this patient, however, flexible bronchoscopy showed a patent RML bronchus. No absolute contraindications to rigid bronchoscopy were noted, nor did concerns arise regarding RA-related upper airway obstruction. The cervical spine range of motion was normal, and dynamic (flexion-extension) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed no evidence of cord compression. Entrapment of the right pulmonary artery by the tumor (see Figure 22-1) could result in hemodynamic instability during general anesthesia owing to high risk for acute cor pulmonale.

Expected Results

Relief of BI obstruction was expected to improve her lung function and potentially her dyspnea by restoring ventilation to the right middle lobe. A vast majority of patients with malignant central airway obstruction (CAO) improve their dyspnea and performance status if the CAO is palliated. The modality used to restore airway patency (i.e., laser, stent, photodynamic therapy [PDT], electrocautery, or brachytherapy) depends on tumor characteristics (i.e., extrinsic, endoluminal, or mixed) and severity and type of obstruction (i.e., critical, compromising respiratory status), operator preference, and availability of specific technologies.18 The modality used to restore airway patency might not make a difference in terms of outcome, suggesting that it is restoration of airway patency per se that counts, not the method used to achieve it.19 Survival may also be improved, especially if further systemic therapy can be initiated post procedure. Overall, the median survival of patients with untreated malignant CAO can be as low as 1 to 2 months.20 If interventional bronchoscopy is successful in relieving airway obstruction, survival is similar to that in patients without CAO.21 Stent insertion results in significant improvement in Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scales (MRC)-measured dyspnea and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, although in one study, a significant survival advantage was seen only in the intermediate performance group (ECOG ≤3, MRC ≤4) when compared with historic controls. Perhaps improved survival is noted if airway patency is restored before the development of complications such as post obstructive pneumonia, irreversible atelectasis, or loss of ventilatory function from malignant CAO.22

Therapeutic Alternatives

• External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) for recurrent locally advanced NCSLC previously treated with radiation therapy is a feasible, noninvasive therapeutic alternative.23 However, when associated severe airway obstruction results in atelectasis, the response rate is 20% to 50% in studies involving more than 50 patients.24 Smaller studies showed that bronchial obstruction could be relieved in up to 74% of patients, resulting in complete or partial re-expansion of the collapsed lung. The time to initiation of treatment matters because 71% of patients irradiated within 2 weeks after radiologic evidence of atelectasis had complete re-expansion of their lungs, compared with only 23% of those irradiated after 2 weeks.25 In our patient, EBRT was potentially limited by evidence of radiation-induced toxicity from previous radiotherapy. Improvements in imaging and treatment planning using three-dimensional (3D) conformational radiation and respiratory gating can precisely target radiotherapy, and by decreasing the normal tissue margins included to account for uncertainties in position, can diminish the risk of clinically significant pneumonitis and esophagitis.26

• Endobronchial brachytherapy (EBB) has proven efficacy in patients with endoluminal tumor and a substantial extrabronchial component. For palliation of NSCLC symptoms, EBB alone appears to be less effective than EBRT. For this patient previously treated with EBRT, who was symptomatic from recurrent endobronchial CAO, EBB is a reasonable alternative.27 Success rates vary between 53% and 95%,28 but the overall incidence of fatal hemoptysis is 10% (range, 0% to 42%). Irradiation in the vicinity of major vessels, in this case the right pulmonary artery, increases bleeding risk.29 In fact some authors suggest that patients with tumors involving the major vessels should be excluded from EBB.30 Squamous cell pathology and tumor located in the mainstem bronchus or upper lobe represent additional risk factors for hemoptysis.31 Patients with poor performance status may be at higher risk for periprocedural complications such as cough, bronchospasm, and pneumothorax caused by catheter placement.

• Photodynamic therapy (PDT) could be provided, but because of the severe nature of the airway obstruction, the sloughed tissue resulting from PDT could occlude the airway and cause complete obstruction, resulting in worsening symptoms and post obstructive pneumonia.32 This patient’s previous surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy did not represent contraindications to PDT, and in fact this therapy can be offered to patients who become unresponsive to chemotherapy or radiation therapy.33 PDT is most effective when obstruction from mucosal disease is greater than 50% and in patients with good performance status.34 Hemorrhage has been reported in 0 to 2.3% of patients, but the risk may be greater when the disease involves major blood vessels.

• Cryotherapy would address only the endoluminal component of the obstructing airway lesion. It can be combined with EBRT to enhance its efficacy.35 The effect is delayed, and initially sloughed tissue resulting from vasoconstriction and necrosis might worsen airway obstruction. Cryotherapy is reportedly effective in up to 75% of patients with lung cancer with endoluminal obstruction,36 but it is not the therapy of choice when extrinsic compression is present.

• Argon plasma coagulation (APC) and electrocautery allow removal of exophytic disease.18 Systemic, life-threatening APC-related gas embolism has been reported.37 Risks may be increased when highly vascularized lesions are treated and in proximity of large blood vessels. Depth of penetration and distribution of thermal-induced necrosis within tissues are not as predictable as they are with lasers because electrical current follows the path of least electrical resistance within different tissue types.

• Metal stents are more costly than silicone stents, but procedures can be performed via flexible bronchoscopy with or without fluoroscopy.38 Therefore it is an appropriate alternative, especially in patients with significant comorbidities precluding general anesthesia.

• Silicone Y stent insertion at the right primary carina (RC1) was shown to improve symptoms in a small published case series of three patients with malignant disease. The bronchial limbs of the stent saddled the involved carina between the bronchus to the right upper lobe and the bronchus intermedius.39 The very wide RC1 and the near complete obstruction in the RUL bronchus precluded this approach in our patient.

• Comfort care without palliative bronchoscopic intervention is not an unreasonable approach to treating this patient with poor quality of life and a grim prognosis. A palliative care consultation and potential initiation of hospice care, especially if quality of life continues to deteriorate, should be considered, regardless of other therapeutic alternatives.

Cost-Effectiveness

To our knowledge, no formal cost-effectiveness evaluations of these various modalities have yet been published, but investigators report potential cost savings by implementing an airway program and timely (at diagnosis) bronchoscopic palliation of malignant CAO.22 Long hospitalizations and sojourns on mechanical ventilation are often avoided by rapidly initiating bronchoscopic palliation of airway obstruction or, in case palliative treatments are not selected, by referring patients for best supportive care and hospice.

Techniques and Results

Anatomic Dangers and Other Risks

The proximal BI is surrounded by the right inferior pulmonary artery at the lateral wall and the right inferior pulmonary vein at the medial wall. In this patient, however, anatomy was distorted by her previous lobectomy, and the right main pulmonary artery was adjacent to the anterolateral wall of BI (see Figure 22-1). Displacement of anatomic structures must be expected in planning and performing bronchoscopic intervention, especially when lasers are being used. Deep Nd:YAG laser photocoagulation of tumor in the proximal BI is dangerous, given the proximity of the pulmonary artery already involved with tumor. Overly aggressive coring out, or inadvertent deep photocoagulation with resultant necrosis, could lead to perforation, uncontrollable hemorrhage, and death, even many days after the procedure.

Results and Procedure-Related Complications

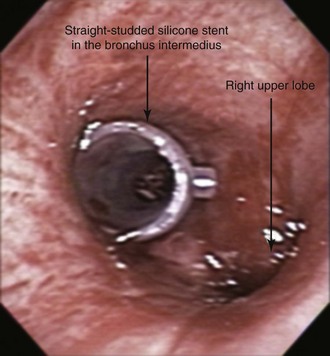

The patient was intubated initially with an 11 mm Efer-Dumon rigid ventilating bronchoscope. The tumor was seen obstructing the BI and the RUL bronchus (see Figure 22-1). The flexible bronchoscope was advanced through the rigid scope, and inspection of the distal airways was attempted. Because the RML segments were patent (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video V.22.1![]() ), we decided that stent insertion in the BI was warranted. The RUL bronchial tumor, characterized by extrinsic compression, was not addressed because of concern for airway perforation and major bleeding in view of pulmonary artery involvement. The Nd:YAG laser was used at 30 W power and 1 second pulses for a total of 100 Joules, and high-power density was used to vaporize the exophytic component of the tumor before the rigid bronchoscope was advanced in the distal BI. Using the bevel edge of the bronchoscope, a small amount of necrotic tumor was cored out from the BI, thereby restoring airway patency. The bronchoscope was removed, and the patient was reintubated using a 12 mm Efer-Dumon rigid ventilating bronchoscope. With the rigid scope in the distal BI, a 12 × 30 mm studded silicone stent was deployed (Figure 22-2). Saline washes performed through the flexible bronchoscope confirmed the absence of pus or excess necrotic material within the BI and the RML bronchus. The case lasted 60 minutes with no bleeding or hemodynamic instability. Extubation was well tolerated, and the patient was kept in the intensive care unit (ICU) for 24 hours, during which no complications were noted. She returned to the referring facility shortly thereafter.

), we decided that stent insertion in the BI was warranted. The RUL bronchial tumor, characterized by extrinsic compression, was not addressed because of concern for airway perforation and major bleeding in view of pulmonary artery involvement. The Nd:YAG laser was used at 30 W power and 1 second pulses for a total of 100 Joules, and high-power density was used to vaporize the exophytic component of the tumor before the rigid bronchoscope was advanced in the distal BI. Using the bevel edge of the bronchoscope, a small amount of necrotic tumor was cored out from the BI, thereby restoring airway patency. The bronchoscope was removed, and the patient was reintubated using a 12 mm Efer-Dumon rigid ventilating bronchoscope. With the rigid scope in the distal BI, a 12 × 30 mm studded silicone stent was deployed (Figure 22-2). Saline washes performed through the flexible bronchoscope confirmed the absence of pus or excess necrotic material within the BI and the RML bronchus. The case lasted 60 minutes with no bleeding or hemodynamic instability. Extubation was well tolerated, and the patient was kept in the intensive care unit (ICU) for 24 hours, during which no complications were noted. She returned to the referring facility shortly thereafter.

Long–Term Management

Referral

We did not recommend additional radiation therapy to her referring physician but suggested consultation with radiation oncology, oncology, and palliative medicine specialists.*

Quality Improvement

We reflected on quality practice in this case. After airway patency had been restored, the patient improved subjectively and was promptly transferred to the care of her physicians at the outside hospital. We did not recommend additional external beam radiation therapy because we were aware that the role of postoperative radiotherapy in patients with completely resected stage III NSCLC is uncertain and may be influenced by the extent of nodal involvement and the use of adjuvant chemotherapy. Results from studies suggest that although postoperative radiotherapy may prevent loco-regional recurrence, it may not significantly alter survival because this is often limited by the development of distant metastatic disease. Retrospective Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database analysis and the Adjuvant Navelbine International Trialist Association (ANITA) trial subset analysis suggest that postoperative radiotherapy may improve survival in patients with N2 lymph node involvement.40 Our patient did not have N2 involvement on pathologic staging, but postoperative radiotherapy could have been offered, given her positive resection margins.

Discussion Points

1. Enumerate four anesthesia considerations during rigid bronchoscopic laser resection in this patient in light of severe bronchial obstruction and pulmonary artery involvement.

2. Enumerate three different types of stents that could be inserted in this patient with incomplete obstruction of the bronchus intermedius and RUL bronchus.

3. Explain differences in tissue penetration and coagulation effects of Nd:YAG, CO2, and KTP lasers, and describe pertinent clinical implications for treating obstructive airway lesions.

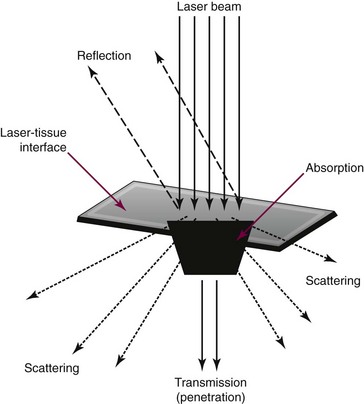

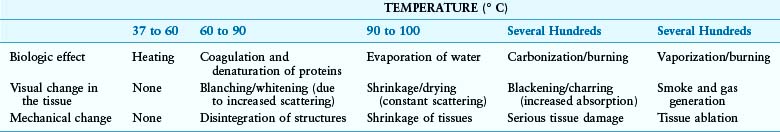

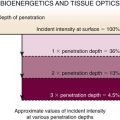

Laser selection requires an understanding of the reflective, absorptive, scattering, and transmissive properties of the target tissue (Figure 22-3).*

4. Describe the principle of power density and its effect on tissues when the Nd:YAG laser is used.

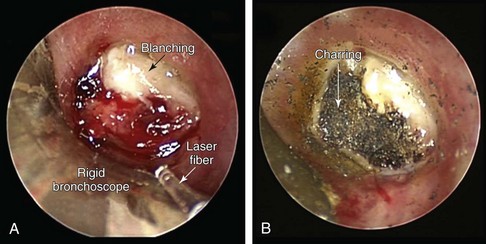

Figure 22-4 Visual changes on a tumor completely occluding the bronchus intermedius during laser application. A, Blanching (from coagulation and denaturation of proteins) is seen after a neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser was used at low power density. B, After laser use at high power density, part of the tumor shows charring (burning) as the result of carbonization effects.*

Expert Commentary

External bean irradiation is a curative treatment option in patients who develop loco-regional recurrence after surgical resection.46 If disease extent is limited to the right hilum, external beam irradiation planned using a four-dimensional CT scan and delivered using intensity-modulated radiotherapy will allow for high-dose repeat irradiation, while limiting doses to the spinal cord, esophagus, and lung parenchyma.47 The risks of radiation-induced toxicity, including risks for pulmonary hemorrhage and late bronchial stenosis, will depend in part on the prior radiation dose received. If a dose of 45 Gy was administered, additional high-dose radiotherapy may be given, considering that a dose of 74 Gy is currently being evaluated in the experimental arm of the RTOG 0617 phase III trial in North America.48 Older literature has reported on outcomes after high-dose re-irradiation for recurrences after previous radiotherapy; long-term disease control with acceptable acute and late toxicity has been described.23,49,50 The risk-benefit ratio of delivering a dose of up to 60 Gy is expected to be better with the use of currently available techniques.

1. Hollingsworth HM. Wheezing and stridor. Clin Chest Med. 1987;8:231-240.

2. Winfield J, Young A, Williams P, et al. Prospective study of the radiological changes in hands, feet, and cervical spine in adult rheumatoid disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1983;42:613-618.

3. Bland JH. Rheumatoid subluxation of the cervical spine. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:134-137.

4. Campbell RS, Wou P, Watt I. A continuing role for pre-operative cervical spine radiography in rheumatoid arthritis? Clin Radiol. 1995;50:157-159.

5. Mikulowski P. Sudden death in rheumatoid arthritis with atlanto-axial dislocation. Acta Med Scand. 1975;198:445-451.

6. Neva MH, Hakkinen A, Makinen H, et al. High prevalence of asymptomatic cervical spine subluxation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis waiting for orthopaedic surgery. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:884-888.

7. Geterud A, Bake B, Berthelsen B, et al. Laryngeal involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Otolaryngol. 1991;111:990-998.

8. Geterud A, Ejnell H, Mansson I, et al. Severe airway obstruction caused by laryngeal rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1986;13:948-951.

9. Wattenmaker I, Concepcion M, Hibberd P, et al. Upper-airway obstruction and perioperative management of the airway in patients managed with posterior operations on the cervical spine for rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:360-365.

10. Bandi V, Munnur U, Braman SS. Airway problems in patients with rheumatologic disorders. Crit Care Clin. 2002;18:749-765.

11. Abrams TE, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Rosenthal GE. Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on surgical mortality. Arch Surg. 2010;145:947-953.

12. Jung C, Inder JW. Management of adrenal insufficiency during the stress of medical illness and surgery. Med J Aust. 2008;188:409-413.

13. Naber D, Sand P, Heigl B. Psychopathological and neuropsychological effects of 8-days’ corticosteroid treatment: a prospective study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:25-31.

14. Howard LM, Barley EA, Davies E, et al. Cancer diagnosis in people with severe mental illness: practical and ethical issues. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:797-804.

15. Siddiqui F, Bae K, Langer CJ, et al. The influence of gender, race, and marital status on survival in lung cancer patients: analysis of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trials. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:631-639.

16. Berglund A, Holmberg L, Tishelman C, et al. Social inequalities in non-small cell lung cancer management and survival: a population-based study in central Sweden. Thorax. 2010;65:327-333.

17. Tishelman C, Petersson LM, Degner LF, et al. Symptom prevalence, intensity, and distress in patients with inoperable lung cancer in relation to time of death. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5381-5389.

18. Ernst A, Feller-Kopman D, Becker HD, et al. Central airway obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:1278-1297.

19. Santos RS, Raftopoulos Y, Keenan RJ, et al. Bronchoscopic palliation of primary lung cancer: single or multimodality therapy? Surg Endosc. 2004;18:931-936.

20. Macha HN, Becker KO, Kemmer HP. Pattern of failure and survival in endobronchial laser resection: a matched pair study. Chest. 1994;105:1668-1672.

21. Chhajed PN, Baty F, Pless M, et al. Outcome of treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer with and without central airway obstruction. Chest. 2006;130:1803-1807.

22. Razi SS, Lebovics RS, Schwartz G, et al. Timely airway stenting improves survival in patients with malignant central airway obstruction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:1088-1093.

23. Okamoto Y, Murakami M, Yoden E, et al. Reirradiation for locally recurrent lung cancer previously treated with radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:390-396.

24. Slawson RG, Scott RM. Radiation therapy in bronchogenic carcinoma. Radiology. 1979;132:175-176.

25. Reddy SP, Marks JE. Total atelectasis of the lung secondary to malignant airway obstruction: response to radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1990;13:394-400.

26. Decker RH, Wilson LD. Advances in radiotherapy for lung cancer. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29:285-290.

27. Cardona AF, Reveiz L, Ospina EG, et al. Palliative endobronchial brachytherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2008. CD004284

28. Scarda A, Confalonieri M, Baghiris C, et al. Out-patient high-dose-rate endobronchial brachytherapy for palliation of lung cancer: an observational study. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2007;67:128-134.

29. Hara R, Itami J, Aruga T, et al. Risk factors for massive hemoptysis after endobronchial brachytherapy in patients with tracheobronchial malignancies. Cancer. 2001;92:2623-2627.

30. Khanavkar B, Stern P, Alberti W, Nakhosteen JA. Complications associated with brachytherapy alone or with laser in lung cancer. Chest. 1991;99:1062-1065.

31. Macha HN, Wahlers B, Reichle C, et al. Endobronchial radiation therapy for obstructing malignancies: ten years’ experience with iridium-192 high-dose radiation brachytherapy afterloading technique in 365 patients. Lung. 1995;173:271-280.

32. Moghissi K, Dixon K. Is bronchoscopic photodynamic therapy a therapeutic option in lung cancer? Eur Respir J. 2003;22:535-541.

33. Moghissi K, Dixon K, Stringer M, et al. The place of bronchoscopic photodynamic therapy in advanced unresectable lung cancer: experience of 100 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15:1-6.

34. Edell ES, Cortese DA. Photodynamic therapy: its use in the management of bronchogenic carcinoma. Clin Chest Med. 1995;16:455-463.

35. Vergnon JM, Schmitt T, Alamartine E, et al. Initial combined cryotherapy and irradiation for unresectable non-small cell lung cancer: preliminary results. Chest. 1992;102:1436-1440.

36. Vergnon JM, Huber RM, Moghissi K. Place of cryotherapy, brachytherapy and photodynamic therapy in therapeutic bronchoscopy of lung cancers. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:200-218.

37. Reddy C, Majid A, Michaud G, et al. Gas embolism following bronchoscopic argon plasma coagulation: a case series. Chest. 2008;134:1066-1069.

38. Alazemi S, Lunn W, Majid A, et al. Outcomes, health-care resources use, and costs of endoscopic removal of metallic airway stents. Chest. 2010;138:350-356.

39. Oki M, Saka H, Kitagawa C, et al. Silicone Y-stent placement on the carina between bronchus to the right upper lobe and bronchus intermedius. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:971-974.

40. Douillard JY, Rosell R, De Lena M, et al. Adjuvant vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus observation in patients with completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (Adjuvant Navelbine International Trialist Association [ANITA]): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:719-727.

41. Ramser ER, Beamis JrJF. Laser bronchoscopy. Clin Chest Med. 1995;16:415-426.

42. Colt HG. Laser bronchoscopy. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1996;2:277.

43. Vanderschueren RG, Westermann CJ. Complications of endobronchial neodymium-YAG (Nd:YAG) laser application. Lung. 1990;168:1089.

44. Mackie AM, Watson CB. Anaesthesia and mediastinal masses: a case report and review of the literature. Anaesthesia. 1984;39:899-903.

45. Fisher JC. The power density of a surgical laser beam: its meaning and measurement. Lasers Surg Med. 1983;2:301-315.

46. Jeremic B, Shibamoto Y, Milicic B, et al. External beam radiation therapy alone for loco-regional recurrence of non-small-cell lung cancer after complete resection. Lung Cancer. 1999;23:135-142.

47. Haasbeek CJ, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Radiotherapy for lung cancer: clinical impact of recent technical advances. Lung Cancer. 2009;64:1-8.

48. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. RTOG clinical trials listed by study number. www.rtog.org/ClinicalTrials/ProtocolTable.aspx. Accessed February 12, 2012

49. Wu KL, Jiang GL, Qian H, et al. Three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for locoregionally recurrent lung carcinoma after external beam irradiation: a prospective phase I-II clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57:1345-1350.

50. Tada T, Fukuda H, Matsui K, et al. Non-small-cell lung cancer: reirradiation for loco-regional relapse previously treated with radiation therapy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2005;10:247-250.

* Following life-prolonging procedures, it is common for patients to request continued care at the tertiary institution providing the procedure. This obviously creates an ethical dilemma: Should the performing physician continue to provide care to the patient at his/her institution, at the patient’s request, or should he or she insist on continued care from the referring health care providers? The answer depends on the capability of the referring facility to provide comprehensive cancer care.

* However, several nonlinear events may occur with very short pulses (nanoseconds or picoseconds): multiphoton absorption, plasma formation, and ionization.

† This would not be the case for an insignificant divergence of a truly collimated laser beam (effectively, a parallel beam of light with very low divergence or convergence), but through multiple internal reflections of a laser fiber, the transmitted beam loses its collimation and emerges with a 10 to 12 degree spread of divergence.

* The conversion of organic substances into carbon or carbon-containing residue through thermochemical decomposition at elevated temperatures (aka pyrolysis).