Chapter 25 Rigid Bronchoscopy for Removal of a Foreign Body Lodged in the Right Lower Lobe Bronchus

Case Description

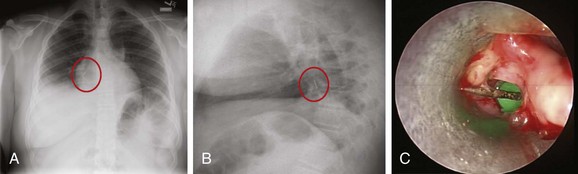

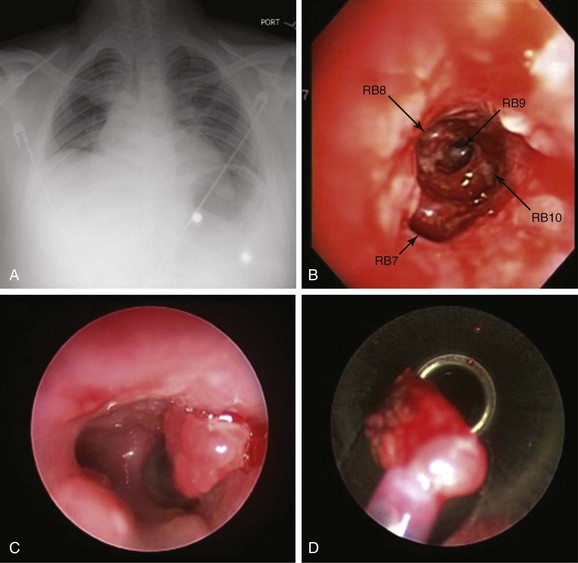

A 14-year-old male with a past medical history of asthma developed acute cough and wheezing immediately following an episode of intense laughter. Actually, he was holding a thumbtack between his teeth when his brother made a funny comment. Bursting into laughter, he suddenly aspirated the thumbtack. He did not tell his parents. Several days later, his intractable cough prompted his parents to bring him to the hospital, where he told physicians about the accident. Flexible bronchoscopy revealed the foreign object in the distal left main bronchus, but despite multiple attempts, it could not be removed and was inadvertently dropped over and into the right bronchial tree. He was transferred to our facility a few days later. His vital signs showed a BP of 150/85, HR of 110, RR of 22, temperature of 100.5° F, and O2 sat of 94% on room air. On examination, he had no wheezing, but air entry at the right base was diminished. The child was a nonsmoker and had no significant family history. His asthma was well controlled on inhaled fluticasone 110 mcg twice a day, with which he was usually noncompliant. Laboratory data were normal, except for a WBC of 18,000. Chest radiograph showed a radiopaque object projecting over the right lower lung field (Figure 25-1). During rigid bronchoscopy, a thumbtack surrounded by inflamed mucosa and granulation tissue was found and was causing complete obstruction of the right lower lobe bronchus (see Figure 25-1).

Discussion Points

1. List five accessory instruments that can be used to remove a foreign body from the airway.

2. List three complications that might occur during attempts to remove a sharp or pointed object from a lower lobe bronchus.

3. Describe the advantages and disadvantages of flexible bronchoscopy and rigid bronchoscopy for removing aspirated foreign bodies.

Case Resolution

Initial Evaluations

Physical Examination, Complementary Tests, and Functional Status Assessment

This patient’s presentation was classic for foreign body aspiration (FBA), defined as the inhalation of an organic or inorganic foreign object into the larynx and respiratory tract.1 The object was in the right lower lobe, but when a foreign body is in the trachea, patients may have a brassy cough, with or without loss of voice, and bidirectional (during inspiration and expiration) stridor. Complete airway obstruction and asphyxia can develop when a large object is lodged in the trachea or larynx.2 Cyanosis, stridor, and altered level of consciousness are ominous signs and predict impending respiratory arrest.

As in this case, signs predictive of bronchial FBA include radiopaque objects seen on chest x-ray (CXR), a history of FBA associated with unilaterally decreased breath sounds, localized wheezing, focal hyperinflation, and atelectasis (this is usually a later finding, which occurs after air has been resorbed). Prompt diagnosis is essential, especially in children, because results from studies show that complication rates are twofold higher in patients who receive medical attention 2 or more days after the aspiration, compared with patients cared for sooner.3 Physical examination in patients with bronchial FBA may reveal unilateral wheezing, which suggests partial airway obstruction distal to the carina.4,5 By the time our patient came to our institution, wheezing had ceased, probably complete obstruction had developed, and there was no longer any airflow to the right lower lobe (RLL) bronchus.

Chest radiograph is a commonly performed imaging modality for suspected FBA in a stable patient. Standard frontal and lateral views can help locate the object (see Figure 25-1).4 Lateral soft tissue views of the neck are performed if upper airway involvement is suspected clinically. If the patient is critical and suspicion for FBA is high based on the history and physical examination, CXR is not absolutely necessary, and airway management should take priority. Characteristic findings on CXR depend on the density of the aspirated object and on the duration of symptoms. Radiopaque materials such as coins, thumbtacks, metallic nails, toys, bones, teeth, and dental appliances usually can be detected on radiographs. Radiopaque foreign bodies, however, are seen in only 2% to 19% of patients with FBA because most aspirated objects are radiolucent. Furthermore, radiopaque material seen on x-ray may actually represent calcifications of mucoid impaction or a broncholith, and thus could be a false-positive finding. In fact, the sensitivity of CXR performed in the emergency department for FBA is reportedly only 22.6%. False-negative rates vary between 5% and 30% in children and between 8% and 80% in adults, probably because of differences in physical properties of aspirated materials. For example, organic materials such as meat and vegetables are difficult to visualize because they are not radiopaque.6,7 When the aspirated material is radiolucent and is not identified on chest x-ray, nonspecific CXR findings that suggest FBA include atelectasis, pneumonia, air trapping, and pneumomediastinum. Air trapping is an early radiographic finding that results from obstruction of the airway by the foreign body, which acts as a ball valve, allowing air to enter the bronchus but not to exit during expiration. Expiratory and inspiratory chest x-rays, when feasible, may help detect any air trapping.8 In children with aspirated foreign bodies, the absence of air trapping was found to have a negative predictive value of 70%.9 However, because overall sensitivity is low, a normal CXR, does not preclude additional diagnostic studies such as chest computed tomography (CT), which can detect foreign bodies not visualized on CXR in up to 80% of cases.10 This modality is particularly useful in patients with chronic respiratory symptoms or with recurrent pneumonia. False-negative CT scans, especially with 10 mm slice thickness, may occur because CT can miss small objects, and because image quality is compromised by motion artifacts in patients with severe dyspnea.4 CT findings include visualizing the foreign body in the airway lumen and observing indirect findings such as atelectasis, hyperlucency, bronchiectasis, lobar consolidation, tree-in-bud opacities, ipsilateral pleural effusion, ipsilateral lymphadenopathy, and thickening of the bronchial wall adjacent to the foreign body.

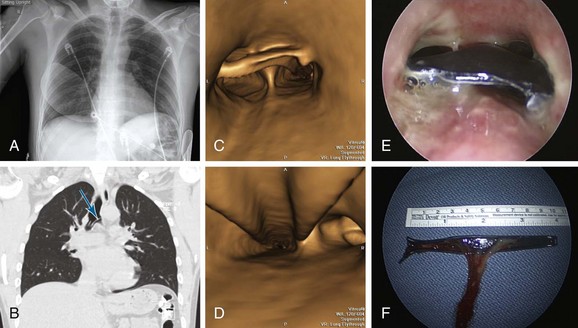

In children, low-dose multidetector CT (MDCT) scanning and virtual bronchoscopy (VB) (Figure 25-2) have a sensitivity of 92% to 100% and a specificity of 80% to 85%.11,12 False-positives occur because of secretions and endobronchial tumors. Therefore MDCT and VB, if available and when feasible, can be used as noninvasive tools to confirm FBA and to determine the exact location of the obstruction before bronchoscopy. Some authors suggest that in the presence of a positive clinical diagnosis and a negative CXR, VB should be considered in all children with suspected FBA to avoid a potentially unwarranted rigid bronchoscopy.12

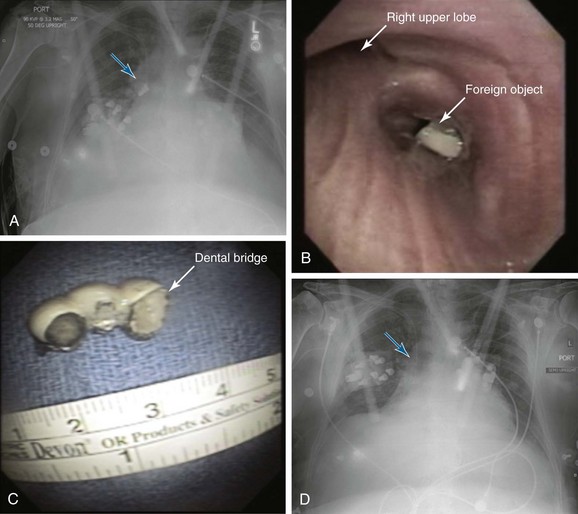

In stable adults, flexible bronchoscopy should be used to confirm suspected cases of FBA and to attempt removal of the foreign body.4 This is also true for victims of cervicofacial trauma (Figure 25-3). Rigid bronchoscopy usually is not indicated in these patients because of neck immobilization. In addition to allowing removal of the FB, bronchoscopy determines the exact nature of the foreign body, its location and degree of airway obstruction, and associated mucosal abnormalities such as surrounding mucosal edema and granulation tissue (see Figure 25-3). In patients presenting with acute asphyxia, flexible bronchoscopy or rigid bronchoscopy can be performed, depending on availability. In stable children with suspected FBA, flexible bronchoscopy has been shown to safely confirm the diagnosis and has been used to extract foreign objects5; it provides rapid and definitive diagnosis of FBA in approximately 12% of children who present with persistent wheezing (lasting longer than 6 weeks and not responding to bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids).13 Controversy continues, however, because some authorities recommend rigid bronchoscopy in children younger than 12 years of age when there is a strong suspicion of FBA, arguing that rigid bronchoscopy permits better control and visualization of the pediatric airway.14

Comorbidities

Our patient had controlled asthma on inhaled corticosteroids. Although acute asthma exacerbation was in the differential diagnosis, wheezing in asthma is usually paroxysmal, intermittent, and diffuse and improves after bronchodilators. Symptoms are triggered by exercise, cold, sleep, and allergens, and the CXR usually shows peribronchial cuffing and bilateral hyperinflation. The presence of these findings, however, would not rule out FBA.15 Indeed, dyspnea alters the coordination between deglutition and respiration, increasing the risk for aspiration.16

Our patient had no evidence of dysphagia or impaired cough reflex.4 These conditions are usually seen in the elderly, especially in cases of cerebrovascular or degenerative neurologic disease. More than one third of patients with acute stroke have radiologic evidence of aspiration.17 Patients with dysphagia have delayed triggering of the pharyngeal motor response and decreased laryngeal elevation, resulting in poor coordination and timing of oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal movement during swallowing.18 Anticholinergics, antipsychotics, and anxiolytics also impair the cough reflex and/or swallowing.

Procedural Strategies

Indications

Although some controversy continues, most clinicians agree that rigid bronchoscopy is indicated in patients with FBA associated with stridor or asphyxia, as well as in children with radiopaque objects seen on CXR (because the diagnosis is obvious), a history of FBA associated with localized wheezing, obstructive hyperinflation, atelectasis, or unilaterally decreased breath sounds suggesting mainstem bronchial obstruction. Large, round, or smooth foreign bodies probably are best approached with the rigid bronchoscope (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.25.1![]() ).

).

In other cases, flexible bronchoscopy should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and attempt removal. Although this procedure is safe, effective, and cost-effective, dislodgment and unsuccessful retrieval of the object are possible.14 Potential complications of attempting to remove large foreign bodies with a fiberoptic bronchoscope include displacement or impaction of the foreign body in a lobar or mainstem bronchus, shearing off of the foreign body in the narrow subglottic area, and acute asphyxia from subglottic or laryngeal obstruction.19 If flexible bronchoscopy fails, rigid bronchoscopy is warranted.9 Advantages of rigid bronchoscopy include the ability to function as an endotracheal tube, securing the airway and providing a conduit through which the foreign body can be removed using a variety of larger instruments. As mentioned earlier, however, flexible bronchoscopy remains the method of choice for patients with cervicofacial trauma (see Figure 25-1) and for those who are already intubated.4

Contraindications

This patient’ s asthma was not a contraindication to bronchoscopy, but optimal control before the intervention is warranted; studies have shown that even patients with mild asthma have a more pronounced post bronchoscopy decrease in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) compared with normal subjects. Reductions in FEV1 and forced vital capacity (FVC) are especially greater after bronchioloalveolar lavage and biopsies.20 Bronchoscopy is safe in asymptomatic asthmatic patients with FEV1 >60% predicted.21 Premedication with bronchodilators was associated with no fall in post procedure FEV1.22 This is different from COPD, in which premedication with an inhaled short-acting agonist is not routinely recommended (in COPD, bronchodilators have not been shown to affect post procedure reduction in FEV1).23

If patients have active diffuse wheezing, premedication with nebulized bronchodilators is warranted, and in elective cases, the procedure might have to be postponed until bronchospasm is controlled. One large study found that bronchoscopic interventions in asthmatic patients were associated with significantly higher rates of procedure- or anesthesia-related complications such as laryngospasm or bronchospasm, status asthmaticus, severe hypoxemia, and cardiac arrest, compared with interventions in nonasthmatic patients.24

Expected Results

Both flexible and rigid bronchoscopy can be performed for removal of foreign bodies, but overall, flexible bronchoscopy seems to be an efficient initial method in both children and adults, with a success rate greater than 90%.5,25 Repeated bronchoscopic examination may be necessary to remove a foreign body completely in 1% to 3% of patients, especially if the foreign body is a peanut or another material that breaks easily.9,14 When flexible bronchoscopy fails, rigid bronchoscopy should be performed,9 as was done in this case. Open surgical interventions are very rarely necessary and are reserved for repeatedly unsuccessful bronchoscopic interventions.

Complications of FBA are usually prevented by prompt removal of the object. A retained object can lead to prolonged atelectasis and lung destruction, occasionally requiring thoracotomy and resection. Early complications of FBA include asphyxia, cardiac arrest, laryngeal edema, and pneumomediastinum. Organic objects, especially those with high oil content such as peanuts, may cause significant mucosal inflammation and bulky granulation tissue growth within a few hours, eventually causing complete bronchial obstruction. Late complications include bronchiectasis, hemoptysis, bronchial stricture, and inflammatory polyps. Objects can change sides, moving from left to right or from right to left, or can migrate distally, causing complete obstruction and atelectasis.14 Table 25-1 summarizes potential complications associated with FBA.

Table 25-1 Potential Complications Due to Foreign Body Aspiration and Its Bronchoscopic Removal

| Complication | Comments |

|---|---|

| Asphyxia | Aspiration of a foreign body is the fifth most common cause of mortality from unintentional injury in the United States, and it is the leading cause of mortality from unintentional injury in children younger than 1 year. |

| Pneumonia | Seen in 20% of patients who present days or weeks after FBA.7 The incidence may be higher with delayed presentation. |

| Atelectasis | Complete obstruction from the foreign body or associated secretions and granulation tissue can cause atelectasis, seen in approximately 20% of patients on CXR and in approximately 60% on chest CT scan.4 |

| Bronchiectasis | On chest CT, this is a late complication that can be seen in about 30% of patients with FBA; occasionally, severe and recurrent infections may require thoracotomy and pulmonary resection. |

| Pneumomediastinum | A rare acute finding on CXR in approximately 3% of patients with FBA.7 |

| Subglottic edema related to rigid bronchoscopy | Between 2% and 4% of patients requiring rigid bronchoscopy for foreign body extraction develop laryngeal edema that requires brief intubation and admission to intensive care.9 |

| Bronchoscopy-related bronchospasm | More than 4% of children who require rigid bronchoscopy for foreign body extraction develop bronchospasm.9 |

| Bronchial stricture | Aspiration of iron or potassium-chloride pills can cause airway inflammation, resulting in fibrosis and bronchial strictures. |

CT, Computed tomography; CXR, chest x-ray; FBA, foreign body aspiration.

Team Experience

Access to both flexible and rigid bronchoscopy is warranted, especially if the bronchoscopist is inexperienced or unskilled in flexible foreign body retrieval. Consultation with a rigid bronchoscopist, who may be a pulmonologist, a thoracic surgeon, or an otorhinolaryngologist, can help in developing a management strategy. Care should always be taken to avoid inadvertently pushing foreign objects more distally into the airway because this will make subsequent retrieval more difficult. Communication among team members is essential. For example, several different foreign body removal accessory instruments should be available, and one should not assume that simple grasping forceps will suffice. If procedures are being performed with the patient under general anesthesia, it may be necessary to cease ventilation to avoid blowing the object away from the grasping instrument. Wedging the foreign object into the rigid bronchoscope or endotracheal tube before removal may be necessary to avoid laryngeal or airway wall injury; sometimes, it is preferable to remove the tube and foreign body en bloc, rather than attempt to remove the foreign body alone. At other times, if the bronchoscopist is taking too long to grasp the object in a distal airway and ventilation is inadequate, a momentary retreat to the mid-trachea is warranted, so the anesthesiologist can ventilate the lungs adequately.26 If a forceps and a bronchoscope are removed en bloc, along with the foreign body, the bronchoscopist should ask the anesthesiologist to deepen the level of anesthesia to avoid bucking or coughing, which may result in dropping of the foreign body back into the airway or inadvertent traumatizing of a closing glottis. Care must also be taken to avoid losing the foreign body in the oral pharynx once the vocal cords have been passed. The foreign object should always be kept in view and grasped firmly. One should be ready to remove the object from the oral cavity using one’s fingers, a Magill forceps, a rigid laryngoscope, or the rigid bronchoscope. It may be necessary to pull the tongue outward (using a gauze to hold the tip of the tongue firmly between one’s index finger and thumb) to create more space in the oropharynx. A retrieval strategy should be shared with the team. For example, we have seen (1) foreign bodies removed by flexible bronchoscopy performed through the nares; once the foreign body is grasped, it is discovered that it is too large to be removed through the nares and thus must be dropped into the oral cavity and extracted, spit out, or accidentally swallowed; (2) foreign bodies grasped with forceps, only to be wedged within the subglottis, causing acute asphyxia; (3) sharp objects stabbing the inferior aspect of the glottis because the object is removed tangentially to the airway in an unprotected fashion; and (4) flexible bronchoscopes being broken because the foreign body is released into the oropharynx. During retrieval, the bite block was loosened and retracted proximally, which exposed the scope to a patient’s teeth during a violent cough.

Therapeutic Alternatives for Foreign Body Removal

1. Flexible bronchoscopy is the method of choice in a patient with cervicofacial trauma because rigid bronchoscopy would be impossible in such a patient, and the only alternative is open thoracotomy. Flexible bronchoscopy is also a reasonable first therapeutic choice in a patient with a foreign body lodged in the distal airways.4 Because patient cooperation facilitates foreign body retrieval by flexible bronchoscopy, this method may not be ideal in very young children.

2. Surgery is indicated if repeated flexible and rigid bronchoscopic attempts fail. Thoracotomy with pulmonary resection is usually reserved for cases of a destroyed pulmonary segment or lobe, or damage to the entire lung.27

Cost-Effectiveness

Rigid bronchoscopy is commonly performed even as a diagnostic approach in children.9,28 However, in cases of suspected but not confirmed FBA, the high rate of negative initial rigid bronchoscopies (11% to 46%) may not justify this approach. The American Thoracic Society considers flexible bronchoscopy a cost-effective alternative in cases of equivocal airway foreign body, avoiding unnecessary rigid bronchoscopy and general anesthesia.29 In children with confirmed radiopaque foreign bodies in the presence of associated unilateral decreased breath sounds and atelectasis, rigid bronchoscopy is often recommended.9 It is reasonable from a cost-effectiveness and a patient comfort/safety perspective to proceed with an attempt at rigid bronchoscopic extraction before considering open thoracotomy.

Informed Consent

This 14-year-old patient had a clear understanding of the risks, benefits, and alternatives to treatment. He was able to describe the procedure, its potential associated complications, and the consequences of not undergoing the procedure. We believed he had the decision-making capacity for health care. Regarding treatment of minors, the recurrent question is whether they should give informed consent, or if this should be provided by parents or legal guardians, who may be seen as more capable of making a knowledgeable decision on a subject as important as a medical intervention. In our society, a trend beyond setting an arbitrary “age of consent” has been noted, with many preferring instead a movement that entertains respect for each individual child’s reflective abilities, in part because a child’s overall life experience is usually more relevant than age with regard to ascertaining a child’s capacity for decision making. The statutory age of consent to treatment varies considerably between countries from 12 to 19 years, illustrating the arbitrary nature of these criteria.30

In our case, both the patient and his family were provided with a verbal description and justification for our management strategy. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents (patient’s father had actually signed the form). To our knowledge, although no state or court in the United States has authorized minors younger than age 12 to make medical decisions for themselves, after the minor becomes a teenager, states begin to digress in terms of decision-making responsibilities.31 In California, “a minor may consent to the minor’s medical care if all of the following conditions are satisfied: (1) The minor is 15 years of age or older; (2) the minor is living separate and apart from the minor’s parents or guardian, whether with or without the consent of a parent or guardian, and regardless of the duration of the separate residence; and (3) the minor is managing his or her own financial affairs, regardless of the source of the minor’s income.”32

In California, an emancipated minor* may consent to medical, dental, and psychiatric care.33 This is a relatively new legal concept. The “mature minor” doctrine allows minors to give consent to medical procedures if they can show that they are mature enough to make a decision on their own. The mature minor doctrine takes into account the age, the situation, and proof of conduct of the minor in determining maturity. Usually, the doctrine has been applied in cases where minors are 16 years of age or older, where they show understanding of the medical procedure in question, and where the procedure is not considered “serious.”†

Techniques and Results

Anesthesia and Perioperative Care

Before the procedure is begun, administration of corticosteroids and antibiotics may lead to better outcomes in children with FBA, and 1 to 2 mg/kg prednisolone for 12 to 24 hours may be useful in reducing inflammation and facilitating FB extraction.34 During this period, spontaneous dislodgment of the FB is possible. The FB may be expectorated or swallowed, or it may migrate to a different airway, causing further mucosal injury. Prophylactic use of corticosteroids to reduce the incidence of subglottic edema probably is not warranted. If evidence reveals post procedure laryngeal edema, steroids (dexamethasone, 0.5 to 1 mg/kg to a maximum dose of 20 mg), aerosolized epinephrine (0.5 mL of 2.25% solution diluted 1 : 6), or inhalation of a helium-oxygen mixture should be considered. The length of stay in the hospital after surgery depends on the patient’s general condition and need for continuing antibiotics or other medications.

Ideally, patients should fast from solids for 4 to 6 hours and from clear liquids for 2 hours to prevent aspiration of gastric contents during the perioperative period. In cases of aspiration of gastric contents, which can occur spontaneously, can result from violent coughing or stress-related vomiting, or can be anesthesia related, the operating table should be immediately tilted to a 30 degree head-down position, thus positioning the larynx at a higher level than the pharynx. This allows gastric contents to drain externally. Once the mouth and the pharynx are suctioned, the airway is secured by endotracheal intubation if necessary. Endotracheal suctioning before initiation of positive-pressure ventilation is essential to avoid forcing aspirated material deeper into the lungs.4,35 Bronchoscopy may be useful if performed promptly to suction the aspirated fluid still present in the central airways or to remove any solid material.36 A nasogastric tube should be inserted to empty the stomach once the airway is secured. Positive-pressure ventilation with positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) can be applied to prevent atelectasis and improve the ventilation-to-perfusion ratio.35 Antibiotics might be necessary in cases of confirmed or suspected infection.

The actual anesthetic management of bronchoscopic FB removal can be challenging.2 During induction for rigid bronchoscopy, spontaneous ventilation can be maintained until it is evident that the patient can be ventilated under anesthesia.28 Spontaneous-assisted ventilation is favored by some anesthesiologists because it allows continuous ventilation during removal of the foreign body. However, foreign bodies may migrate distally during a patient’s deep, spontaneous inspiration. On the other hand, positive-pressure ventilation can push the foreign object distally. Intubation or the use of positive-pressure ventilation combined with muscle relaxants allows for a still airway that facilitates retrieval of the foreign body. However, this technique may result in distal movements of the foreign body, which can make removal more difficult and may lead to ball-valve obstruction.28 Overall, the reported outcomes of these two techniques are similar.37 Jet ventilation-assisted anesthesia has been reported for removal of foreign bodies in adults but is not widely advocated in children, perhaps because clinicians have less experience in using this technique in children, or because jet ventilation is more likely to dislodge the foreign body and cause barotrauma.38,39

Technique and Instrumentation

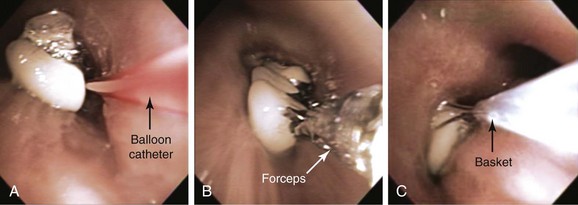

Resuscitation equipment should be readily available in case clinical decompensation occurs as the result of accidental dislodgment of the FB and obstruction of the trachea or larynx. Instruments available for FB extraction include forceps, snares, baskets, suction catheters, Fogarty balloons, and cryotherapy probes. Fogarty balloons are useful for completely lodged objects. The Fogarty catheter can be passed distal to the foreign body. The balloon is inflated and is gently withdrawn until the object is brought up into a larger proximal airway, from which it can be removed with the use of other accessory instruments (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.25.2![]() ). A magnet accessory can be used for metal objects such as nails and pins. Cryotherapy is particularly useful for organic materials that contain water; furthermore, cryotherapy avoids maceration of very friable foreign objects. The object, the probe, and the scope are then removed en masse40 (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.25.3

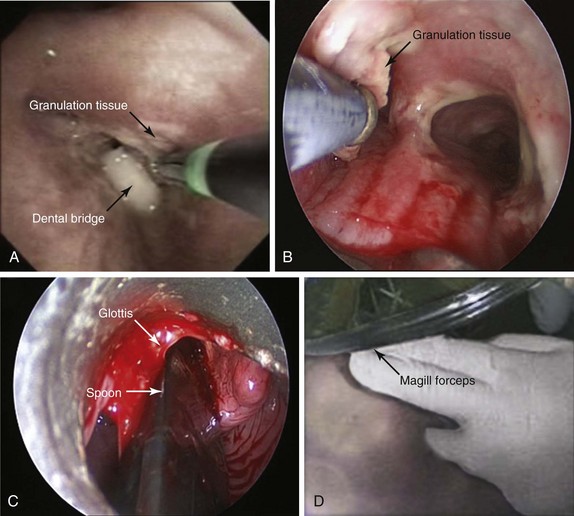

). A magnet accessory can be used for metal objects such as nails and pins. Cryotherapy is particularly useful for organic materials that contain water; furthermore, cryotherapy avoids maceration of very friable foreign objects. The object, the probe, and the scope are then removed en masse40 (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.25.3![]() ). Laser and endobronchial electrosurgery may be used to free an embedded foreign body from the airway wall or to remove associated granulation tissue (Figure 25-4). Sometimes it may be necessary to break the object before removal. This can occasionally be done using neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser, usually at high power density. For example, metal can be cut. In one case, we were unable to grasp a slippery olive pit; we used the laser to make several small incisions in the pit, which could then be used as a hold for grasping forceps.

). Laser and endobronchial electrosurgery may be used to free an embedded foreign body from the airway wall or to remove associated granulation tissue (Figure 25-4). Sometimes it may be necessary to break the object before removal. This can occasionally be done using neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser, usually at high power density. For example, metal can be cut. In one case, we were unable to grasp a slippery olive pit; we used the laser to make several small incisions in the pit, which could then be used as a hold for grasping forceps.

We advise that if the nature of the object is known before intervention, the bronchoscopist can obtain an identical object and practice removal in vitro, thus determining the best instrument and technique to use during the actual procedure.5 If the object is not small enough to fit through the rigid bronchoscope or an endotracheal tube, the object and the scope or endotracheal tube should be removed en bloc with the accessory instrument holding the object (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.25.2![]() ). If the foreign body is lost during retrieval, usually in the narrow subglottis space, the object should be pushed down into a mainstem bronchus to allow sufficient ventilation and oxygenation before retrieval is reattempted. If the object is large or is very long, and if it is lost in the larynx, it can be promptly removed with Magill forceps applied under direct laryngoscopy (see Figure 25-4).

). If the foreign body is lost during retrieval, usually in the narrow subglottis space, the object should be pushed down into a mainstem bronchus to allow sufficient ventilation and oxygenation before retrieval is reattempted. If the object is large or is very long, and if it is lost in the larynx, it can be promptly removed with Magill forceps applied under direct laryngoscopy (see Figure 25-4).

Results and Procedure-Related Complications

After administration of general anesthesia, the patient was intubated with an 11 mm ventilating Efer-Dumon rigid bronchoscope (Bryan Corp., Woburn, Mass). Flexible bronchoscopy was performed through the rigid tube, revealing granulation tissue formation at the distal aspect of the left main bronchus, likely due to the previous presence of the FB in that location. The object was seen in the RLL bronchus. With the rigid bronchoscope wedged in the bronchus intermedius, we used suction to dislodge the object before removal. Because of the metallic and sharp nature of the object, we decided to customize our grasping forceps to avoid loss of the object during retrieval. Nasal cannula tubing was cut, and two short pieces were placed over the jaws of a grasping forceps. The forceps was then advanced carefully under direct visualization. Great care was necessary to avoid pushing the object downward. Both the forceps and the thumbtack were pulled up and were removed en bloc from the airway into the rigid tube (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.25.4![]() ). Rather than remove the tack through the rigid tube, we preferred to extubate the patient, removing the forceps, the tack, and the tube en bloc. Once the object had been removed, the patient was reintubated with the rigid scope, and the airways were carefully re-examined. From the right side, granulation tissue and significant amounts of pus were removed, and washings were performed for microbiologic analysis. No bleeding was noted, but had it occurred, epinephrine (0.25 mg) was available to instill directly onto the airway as an initial step. Flexible bronchoscopy was repeated through the rigid scope and showed patent segmental airways in the RLL. Laser photocoagulation (Nd:YAG 30 Watts power, 1 second pulses) was performed to coagulate a polypoid granulation tissue structure obstructing 40% of the distal left main bronchus (LMB). This was subsequently removed with the use of rigid forceps (Figure 25-5). The patient was extubated and was transferred to the recovery area, where no bronchospasm, laryngospasm, or laryngeal edema was noted.

). Rather than remove the tack through the rigid tube, we preferred to extubate the patient, removing the forceps, the tack, and the tube en bloc. Once the object had been removed, the patient was reintubated with the rigid scope, and the airways were carefully re-examined. From the right side, granulation tissue and significant amounts of pus were removed, and washings were performed for microbiologic analysis. No bleeding was noted, but had it occurred, epinephrine (0.25 mg) was available to instill directly onto the airway as an initial step. Flexible bronchoscopy was repeated through the rigid scope and showed patent segmental airways in the RLL. Laser photocoagulation (Nd:YAG 30 Watts power, 1 second pulses) was performed to coagulate a polypoid granulation tissue structure obstructing 40% of the distal left main bronchus (LMB). This was subsequently removed with the use of rigid forceps (Figure 25-5). The patient was extubated and was transferred to the recovery area, where no bronchospasm, laryngospasm, or laryngeal edema was noted.

Long-Term Management

Outcome Assessment

The patient’s cough improved post intervention. CXR showed improved aeration to the RLL, and the diaphragm was now visualized (see Figure 25-5). The patient was discharged home on antibiotics (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875 mg q 12 hr) for a total of 10 days post intervention.

Quality Improvement

We thought that it was appropriate to educate the patient and the family before the time of discharge about the risks of FBA. We informed them that the risk of FBA is usually higher in older people, especially during and after the seventh decade, probably because of a higher prevalence of aging-associated degenerative neurologic and cerebrovascular disorders that can cause dysphagia and/or impaired cough reflex.4,19 We were aware of studies showing that more than 50% of patients with acute food asphyxiation* are between 71 and 90 years old.41 Young children are at high risk as well because of poor chewing ability, a tendency to put objects in their mouths, and lack of posterior dentition, and because of vigorous inspirations when laughing or crying.9 Risk is greater in children with developmental delay or swallowing difficulties and in males, for whom the risk is almost twice that noted in females.9 This risk is probably a result of the more boisterous behavior of children.9 In the elderly, increased risk is probably caused by higher rates of neurologic and cardiovascular disorders in men.19 Alcohol or sedative use and head trauma are also leading causes of FBA in adults.19 Decreased level of consciousness associated with trauma, use of sedatives or alcohol, general anesthesia, and neurologic disorders such as brain tumor, seizures, Parkinson’s disease, and cerebrovascular accidents impairs airway protection mechanisms and increases aspiration risk.4,19 Aspiration of dental debris, appliances, or prostheses can complicate facial trauma or dental procedures.42 Elderly and neurologically impaired people should eat or be fed small meals of appropriate consistency at a slow pace to prevent choking or regurgitation. The importance of good oral hygiene is also emphasized. Nonrestorable teeth should probably be extracted.

Primary prevention of FBA is important. In the United States, strategies to prevent aspiration of toys and food-related choking among children include (1) efforts by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) to ensure that toys sold in retail store bins, through vending machines, and on the Internet have appropriate choking-hazard warnings, and (2) establishment by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration of surveillance, hazard evaluation, enforcement, and public education activities to prevent food-related choking among children.43 More than 50% of cases of foreign body aspiration occur under the supervision of adults. This suggests that the number and the severity of injuries could be reduced by educating both parents and children.*44

Discussion Points

1. List five accessory instruments that can be used to remove a foreign body from the airway.

2. List three complications that might occur during attempts to remove a sharp or pointed object from a lower lobe bronchus.

3. Describe the advantages and disadvantages of flexible bronchoscopy and rigid bronchoscopy for removing aspirated foreign bodies.

Table 25-2 Advantages and Disadvantages of Flexible and Rigid Bronchoscopy for Foreign Body Removal

| Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Flexible bronchoscopy |

• Preferred in patients with stridor or asphyxia

• May be the initial diagnostic and therapeutic test in children with radiopaque foreign body, or in the presence of associated unilateral decreased breath sounds, localized wheezing, hyperinflation, or atelectasis

• Allows the use of a variety of instruments for foreign body extraction

FBA, Foreign body aspiration.

Expert Commentary

Definitions of Consent

Meanings of consent have developed through international codes on health care research,45,46 which have been extended to apply also to health care treatment. Informed consent includes understanding the nature, duration, and purpose of the intervention, the methods, any risks and inconveniences, the likely effects, and the alternatives. Consent should be voluntary45 and free from constraint or coercion, apart from the inevitable pressures of the problem that requires treatment. The legal origins of consent to health care treatment are comparable with those of consent to marriage, with the aims of respecting free choice and preventing force and coercion. Patients therefore need to know that consent is a choice, not a duty.

An Age of Consent?

The legal age of consent to medical treatment varies between states and countries from 12 to 21 years.30,31 Some American states allow older minors to consent, mainly for three pragmatic reasons: (1) when parents or guardians cannot be contacted during an emergency; (2) when the minor has left home or is married or otherwise independent; (3) when the minor needs treatment for drug, alcohol, sexual, and other problems and does not want the parents to know. Paradoxically, deviant, risk-taking “mature minors” could be seen as more mature than their law-abiding, often better-educated peers, whose consent may not be recognized in law.

Assent is a vague term that ranges from the nonrefusal of young children, to tacit agreement, to the competent consent of minors, whose views are, nevertheless, not recognized in law. Assent lacks the important history, definition, and legal status of consent.47–49

In contrast to the United States, the 54 British Commonwealth countries share the common law Gillick ruling,50 which respects the competence of minors in making decisions and giving informed, voluntary, legally valid consent, without stating a minimum “age of consent.” English law respects the consent of minors if the child’s doctors deem the child to be competent. The law defines competence as having the ability to understand what is involved and the discretion to make a wise choice in the best interests of the child.50 Adults can make any decision for themselves, including self-destructive ones, whereas decisions made by and for minors have to be in their best interests. Best interests are usually defined by the child’s doctors and parents or guardians. However, some children’s independent views are respected and, at times, children understand more about their clinical problems and treatments than their parents do.30,47,51 For example, some very short children give cogent personal reasons for requesting or refusing leg lengthening treatment.51 Surgeons have reported that they will correct a mild case of scoliosis, which they would not usually treat, or that they will withhold or delay treatment for more severe cases, depending on young patients’ strongly reasoned preferences.51 Besides these cosmetic and lifestyle decisions, clinicians respect the decisions of certain minors about attempts to prolong life. At the heart-lung transplant unit in the main children’s hospital in London, after lengthy informed discussion, some children do not consent to join the transplant waiting list.51 Their decision is respected because staff consider that the child’s willing commitment to having a transplant is essential for successful treatment, although they assure children that they can change their mind and return for treatment. Pain, illness, and depression may confuse the decision making of both child and adult patients, which is why careful discussions between doctors and families are vital to analyze flaws and strengths in the patient’s reasoning. Experiences of illness or disability are not entirely negative. They can deepen children’s understanding of complex problems and treatments, and can inform and strengthen their values and aspirations.50,51 To see that illness can have positive aspects connects with another insight, which is essential if patients’ consent is to be understood and respected. This is to move beyond the model of the active informed doctor versus the passive ignorant patient and to recognize how patients too can be informed and active. Much of their health care and well-being is in their hands, as can be seen in daily decisions about the use of inhalers to treat asthma or of physiotherapy to treat cystic fibrosis.47,51

Children who have long-term problems and undergo repeated treatments have time to acquire and reflect on experience and knowledge; this enables them to weigh risks and benefits and to make informed competent decisions.51 This can be harder for unprepared healthy children who suddenly need an urgent intervention such as a bronchoscopy. They may feel too ignorant and shocked, frightened and bewildered, and perhaps too guilty or foolish after inhaling an object, to be able to make a reflective competent decision. Yet skillful clinicians can help young people to overcome these problems, as is shown by the 14-year-old in this chapter, who was assessed by his doctors as able to give informed consent.

Lawyers advise clinicians to involve the parents or guardians of minors and to request their consent, whenever possible, to support or to substitute for the minor’s decision. High standards in pediatric care entail informing and involving all children, competent to consent or not, as far as they are willing and able to take part. Skillful practitioners use the consent process as a teaching and learning dialogue, exploring with children how they can learn and become involved—not simply as a test, which can easily underestimate the child’s capacity. Practitioners who are convinced that children should be warned about risks, in case the intervention fails or damages the child, find that young patients can understand and come to terms with serious risks, at least in nonemergency cases.50,51 If parents want to protect children by keeping them in ignorance, practitioners have to decide who the primary patient is, what obligations they owe to the child, and how much the child already knows and secretly worries about. Risky medical and surgical interventions expose children, who usually are so carefully protected, to exceptional dangers. Clinicians therefore may have to discuss with parents how best to give support as well as honest information to the child during this novel daunting experience.

Four Partially Conflicting Purposes of Consent

Attention to informed and voluntary consent increased over the 20th century.47 Consent serves several purposes. First, respect for their consent or informed refusal expresses principled respect for patients’ human dignity, integrity of mind and body, and right to make personal decisions. Laws protect people from unauthorized touching and intrusion to reduce risks and prevent harms. Ethical standards in medical research45,46 to prevent abuse or neglect have gradually spread and now influence routine standards of respect for consent or refusal in medical treatment.

Second, and pragmatically, patients who are informed and committed to the treatment, in terms of believing that it really is the best option, tend to be more willing and able to cooperate with medical regimens and advice.51–53 When clinicians give clear and detailed information, listen, work through patients’ objections and misunderstandings, and encourage patients’ active cooperation, beyond passive or reluctant compliance, then this consent process becomes part of effective therapy. To force interventions on resisting children is sometimes necessary, but it undermines trusting partnerships between children and doctors on which effective longer-term care depends.

Third, legal standards to protect patients increasingly serve also to protect clinicians and their institutions. Consent is a device that is used to transfer responsibility for risk from the doctor to the informed patient, who signs the statement of knowing acceptance of the risks of unwanted side effects or of ineffective treatment. If patients sue doctors for not giving them adequate information and warning of risk, the signed consent form is a necessary although not sufficient part of doctors’ defense.49 This third purpose potentially sets practitioners against patients, besides exposing patients to responsibility for risk, and this partially conflicts with the first two more protective purposes.

Managing Emotions

Patients and parents may feel anxious and afraid, and at first may fear the dangers of proposed treatment more than the untreated problem. The voluntary consent process involves making an emotional, and often rapid, journey from fear and doubt toward trust and confidence in the treatment and the clinical team.54 Therefore while they increase patients’ doubts through complicated warnings of risk, clinicians simultaneously have to encourage patients to trust and hope.

Research observations of hundreds of consultations between doctors, parents/guardians, and children in England51,54 found that, apart from emergencies in which it might be necessary to proceed without consent, skillful doctors were compassionate (which means “feeling with”) and were also calm and firm. They were confident enough not to feel too threatened by challenging questions. They saw that valid consent involves real hard knowledge about risks, which they explained. They knew that respect for informed consent includes respect for informed refusal. Therefore, to ensure that refusal, if it was expressed, was informed, they listened to objections and discussed misunderstandings. They could accept that, occasionally, children refused treatment because of deeply held values about their quality of life, or their wish to live the final stage of terminal illness at home.

These doctors dexterously managed their own less positive emotions when they felt challenged, as well as the feelings of their young patients and the parents/guardians. Allowing time for patients to change their minds, when possible, could encourage eventual consent. A surgeon and a mother worked for a year to persuade a severely learning disabled girl, aged 12 years, until she felt ready to undergo a series of operations.51 A nurse found that a girl with cystic fibrosis who had been refusing a heart-lung transplant changed her mind “because you listened.”51 In rare cases of irresolvable disputes, doctors apply to courts of law to make the decision to provide or withhold treatment.

1. Marik PE. Aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:665-671.

2. Verghese ST, Hannallah RS. Pediatric otolaryngologic emergencies. Anesthesiol Clin North Am. 2001;2:237-256.

3. Shlizerman L, Mazzawi S, Rakover Y, et al. Foreign body aspiration in children: the effects of delayed diagnosis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31:320-324.

4. Boyd M, Chatterjee A, Chiles C, et al. Tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration in adults. South Med J. 2009;102:171-174.

5. Swanson KL, Prakash UB, Midthun DE, et al. Flexible bronchoscopic management of airway foreign bodies in children. Chest. 2002;121:1695-1700.

6. Paintal HS, Kuschner WG. Aspiration syndromes: 10 clinical pearls every physician should know. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:846-852.

7. Pinto A, Scaglione M, Pinto F. Tracheobronchial aspiration of foreign bodies: current indications for emergency plain chest radiography. Radiol Med. 2006;111:497-506.

8. Kavanagh PV, Mason AC, Müller NL. Thoracic foreign bodies in adults. Clin Radiol. 1999;54:353-360.

9. Righini CA, Morel N, Karkas A, et al. What is the diagnostic value of flexible bronchoscopy in the initial investigation of children with suspected foreign body aspiration? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:1383-1390.

10. Zissin R, Shapiro-Feinberg M, Rozenman J, et al. CT findings of the chest in adults with aspirated foreign bodies. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:606-611.

11. Adaletli I, Kurugoglu S, Ulus S, et al. Utilization of low-dose multidetector CT and virtual bronchoscopy in children with suspected foreign body aspiration. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:33-40.

12. Bhat KV, Hegde JS, Nagalotimath US, et al. Evaluation of computed tomography virtual bronchoscopy in paediatric tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124:875-879.

13. Cakir E, Ersu RH, Uyan ZS, et al. Flexible bronchoscopy as a valuable tool in the evaluation of persistent wheezing in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1666-1668.

14. Martinot A, Closset M, Marquette CH, et al. Indications for flexible versus rigid bronchoscopy in children with suspected foreign-body aspiration. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1676-1679.

15. Martinati LC, Boner AL. Clinical diagnosis of wheezing in early childhood. Allergy. 1995;50:701-710.

16. Warner MA, Warner ME, Warner DO, et al. Perioperative pulmonary aspiration in infants and children. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:66-71.

17. Smith Hammond CA, Goldstein LB. Cough and aspiration of food and liquids due to oral-pharyngeal dysphagia: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(suppl 1):154S-168S.

18. Lundy DS, Smith C, Colangelo L, et al. Aspiration: cause and implications. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:474-478.

19. Limper AH, Prakash UB. Tracheobronchial foreign bodies in adults. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:604-609.

20. Djukanovic R. The safety aspects of fiberoptic bronchoscopy, bronchoalveolar lavage, and endobronchial biopsy in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:772-777.

21. Summary and recommendations of a workshop on the investigative use of fiberoptic bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage in asthmatics. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132:180-182.

22. Rankin J. Bronchoalveolar lavage: its safety in subjects with mild asthma. Chest. 1984;85:723-728.

23. Stolz D, Pollak V, Chhajed PN, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of bronchodilators for bronchoscopy in patients with COPD. Chest. 2007;131:765-772.

24. Lukomsky GI, Ovchinnikov AA, Bilal A. Complications of bronchoscopy: comparison of rigid bronchoscopy under general anesthesia and flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy under topical anesthesia. Chest. 1981;79:316-321.

25. Debeljak A, Sorli J, Music E, et al. Bronchoscopic removal of foreign bodies in adults: experience with 62 patients from 1974-1998. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:792-795.

26. Verghese ST, Hannallah RS. Pediatric otolaryngologic emergencies. Anesthesiol Clin North Am. 2001;19:237-256.

27. Lundy DS, Smith C, Colangelo L, et al. Aspiration: cause and implications. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:474-478.

28. Farrell PT. Rigid bronchoscopy for foreign body removal: anaesthesia and ventilation. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14:84-89.

29. Green CG, Eisenberg J, Leong A, et al. Flexible endoscopy of the pediatric airway. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:233-235.

30. Alderson P. Competent children? Minors’ consent to health care treatment and research. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:2272-2283.

31. E Notes. Treatment of minors. http://www.enotes.com/everyday-law-encyclopedia/treatment-minors. Accessed January 28, 2011

32. Cal. Fam. Code §6922(a) .National Center for Youth Law. www.youthlaw.org. revised January 2003. Accessed January 28, 2011

33. Cal. Fam. Code §7050(e). National Center for Youth Law. www.youthlaw.org. Accessed January 28, 2011

34. Steen KH, Zimmermann T. Tracheobronchial aspiration of foreign bodies in children: a study of 94 cases. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:525-530.

35. Vaughan GG, Grycko RJ, Montgomery MT. The prevention and treatment of aspiration of vomitus during pharmacosedation and general anesthesia. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:874-879.

36. Dines DE, Titus JL, Sessler AD. Aspiration pneumonitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1970;45:347-360.

37. Litman RS, Ponnuri J, Trogan I. Anesthesia for tracheal or bronchial foreign body removal in children: an analysis of ninety-four cases. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:1389-1391.

38. Baraka A. Oxygen enrichment of entrained room air during Venturi jet ventilation of children undergoing bronchoscopy. Paediatr Anaesth. 1996;6:383-385.

39. Eyrich JE, Riopelle JM, Naraghi M. Elective transtracheal jet ventilation for bronchoscopic removal of tracheal foreign body. South Med J. 1992;85:1017-1019.

40. Swanson KL. Airway foreign bodies: what’s new? Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;25:405-411.

41. Wick R, Gilbert JD, Byard RW. Café coronary syndrome—fatal choking on food: an autopsy approach. J Clin Forensic Med. 2006;13:135-138.

42. Weber SM, Chesnutt MS, Barton R, et al. Extraction of dental crowns from the airway: a multidisciplinary approach. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:687-689.

43. Committee on Injury VaPP. Prevention of choking among children. Pediatrics. 2010;125:601-607.

44. Göktas O, Snidero S, Jahnke V, et al. Foreign body aspiration in children: field report of a German hospital. Pediatr Int. 2010;52:100-103.

45. Nuremberg Code, 1947. http://www.cirp.org/library/ethics/nuremberg/. Accessed March 15, 2011

46. Declaration of Helsinki, World Medical Association. http://ohsr.od.nih.gov/guidelines/helsinki.html, 1964/2004. Accessed March 15, 2011

47. Alderson P. Children’s consent and ‘assent’ to healthcare research. In: Freeman M, editor. Childhood and the Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

48. Gillick v. Wisbech and West Norfolk Area Health Authority and the Department of Health and Social Security. http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKHL/1985/7.html. Accessed March 15, 2011

49. Faden R, Beauchamp T. A History and Theory of Informed Consent. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986.

50. Alderson P, Sutcliffe K, Curtis K. Children’s consent to medical treatment. Hastings Centre Report. 2006;36:25-34.

51. Alderson P. Children’s Consent to Surgery. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1993.

52. Alderson P. Choosing for Children: Parents’ Consent to Surgery. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1990.

53. Dose adjustment for normal eating. www.dafne.uk.com. Accessed March 16, 2011

54. Lansdown G, Goldhagen J, Waterston T. Children’s rights and child health: a course for health professionals, American Academy of Pediatrics and Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. http://labspace.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=425620&printable=1, 2010. Accessed March 16, 2011

* A person younger than 18 years is an emancipated minor if any of the following conditions is satisfied: (1) The person has entered into a valid marriage, whether or not the marriage has been dissolved; (2) the person is on active duty with the Armed Forces of the United States; or (3) the person has received a declaration of emancipation from the court. (Cal. Family Code §7002) (National Center for Youth Law; www.youthlaw.org; revised January 2003).

† Outside of reproductive rights, the U.S. Supreme Court has never ruled on applicability to medical procedures (http://www.enotes.com/everyday-law-encyclopedia/treatment-minors).

* The syndrome of fatal or near fatal food asphyxiation is also referred to as café coronary; for practical purposes, it is important to remember that the foreign material is in a supraglottic position in about one third of cases.

* We had a patient who aspirated a coin while he was showing his 10-year-old son how easy it was to flip a coin into the air and catch it in his mouth. This “money-catcher” became the talk of his child’s school.