Chapter 11 Rheumatology and bone disease

Rheumatological and musculoskeletal disorders

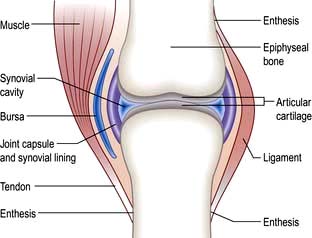

The normal joint

There are three types of joints: fibrous, fibrocartilaginous and synovial.

Synovial joints

These (Fig. 11.1) include the ball-and-socket joints (e.g. hip) and the hinge joints (e.g. interphalangeal).

Juxta-articular bone

The bone which abuts a joint (epiphyseal bone) differs structurally from the shaft (metaphysis) (see Fig. 11.32). It is highly vascular and comprises a light framework of mineralized collagen enclosed in a thin coating of tougher, cortical bone. The ability of this structure to withstand pressure is low and it collapses and fractures when the normal intra-articular covering of hyaline cartilage is worn away as in osteoarthritis (OA; see p. 512). Loss of surface cartilage also leads to the abnormalities of bone growth and remodelling typical of OA (see p. 512).

Ligaments and tendons

These structures stabilize joints. Ligaments are variably elastic and this contributes to the stiffness or laxity of joints (see p. 559). Tendons are inelastic and transmit muscle power to bones. The joint capsule is formed by intermeshing tendons and ligaments. The point where a tendon or ligament joins a bone is called an enthesis and may be the site of inflammation.

Components of extracellular matrix

Collagens. Collagens consist of three polypeptide (α) chains wound into a triple helix. These alpha chains contain repeating sequences of Gly-x-y triplets, where x and y are often prolyl and hydroxypropyl residues. Collagen fibres show genetic heterogeneity, with genes on at least 12 chromosomes. Hyaline cartilage is 90% type II (COL2A1). There are several classes of collagen genes, based on their protein structures, and abnormalities of these may lead to specific diseases (see p. 560).

Skeletal muscle

This consists of bundles of myocytes containing actin and myosin molecules. These molecules interdigitate and form myofibrils which cause muscle contraction in a similar way to myocardial muscle (p. 671). Bundles of myofibrils (fasciculi) are covered by connective tissue, the perimysium, which merges with the epimysium (covering the muscle) and forms the tendon which attaches to the bone surface (enthesis).

Clinical approach to the patient

Taking a musculoskeletal history

Where is it? Is it localized or generalized? The pattern of joint involvement is a useful clue to the diagnosis (e.g. distal interphalangeal joints in nodal osteoarthritis).

Where is it? Is it localized or generalized? The pattern of joint involvement is a useful clue to the diagnosis (e.g. distal interphalangeal joints in nodal osteoarthritis).

Is it arising from joints, the spine, muscles or bone, with local tenderness? Soft tissue lesions and inflamed joints are locally tender.

Is it arising from joints, the spine, muscles or bone, with local tenderness? Soft tissue lesions and inflamed joints are locally tender.

Could it be referred from another site? Joint pain is localized but may radiate distally – shoulder to upper arm; hip to thigh and knee.

Could it be referred from another site? Joint pain is localized but may radiate distally – shoulder to upper arm; hip to thigh and knee.

Is it constant, intermittent or episodic? How severe is it – aching or agonizing?

Is it constant, intermittent or episodic? How severe is it – aching or agonizing?

Are there aggravating or precipitating factors? Is it made worse by activity and eased by rest (mechanical) or worse after rest (inflammatory).

Are there aggravating or precipitating factors? Is it made worse by activity and eased by rest (mechanical) or worse after rest (inflammatory).

Are there any associated neurological features? Numbness, pins and needles and/or loss of power suggest ‘nerve’ involvement. The distribution of symptoms is a useful clue to the nerve or nerve root affected.

Are there any associated neurological features? Numbness, pins and needles and/or loss of power suggest ‘nerve’ involvement. The distribution of symptoms is a useful clue to the nerve or nerve root affected.

Gout (see p. 530), reactive arthritis (p. 529) and ankylosing spondylitis (p. 527) are more common in men. Rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune rheumatic diseases are more common in women.

Is the person young, middle-aged or older?

Is the person young, middle-aged or older?

How old was the patient when the problem first started? Osteoarthritis (see p. 512) and polymyalgia rheumatica (p. 542) rarely affect the under-50s. Rheumatoid arthritis starts most commonly in women aged 30–50 years.

How old was the patient when the problem first started? Osteoarthritis (see p. 512) and polymyalgia rheumatica (p. 542) rarely affect the under-50s. Rheumatoid arthritis starts most commonly in women aged 30–50 years.

Is there any associated ill-health or other worrying feature, such as weight loss or fever?

Is there any associated ill-health or other worrying feature, such as weight loss or fever?

Are there other associated medical conditions that may be relevant? Psoriasis (see p. 1207) or inflammatory bowel disease is associated with spondyloarthritis (see p. 1004). Charcot’s joints (p. 547) are seen in diabetics.

Are there other associated medical conditions that may be relevant? Psoriasis (see p. 1207) or inflammatory bowel disease is associated with spondyloarthritis (see p. 1004). Charcot’s joints (p. 547) are seen in diabetics.

Could a drug be a cause? Diuretics may precipitate gout in men and older women. Hormone replacement therapy or the oral contraceptive pill may precipitate systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (p. 535). Steroids can cause avascular necrosis. Some drugs cause a lupus-like syndrome (p. 535).

Is this relevant? Sickle cell disease causes joint pain in young black Africans, but osteoporosis (see p. 552) is uncommon in older black Africans.

Have there been any similar episodes or is this the first? Are there any clues from previous medical conditions? Gout is recurrent; the episodes settle without treatment in 7–10 days. Acute episodes of palindromic rheumatism may predate the onset of rheumatoid arthritis (see p. 519).

The biopsychosocial model of disease is highly relevant to many rheumatic disorders:

Has there been any recent major stress in family or working life? Could this be relevant? Stress rarely causes rheumatic disease but may precipitate a flare-up of inflammatory arthritis. It reduces a person’s ability to cope with pain or disability.

Has there been any recent major stress in family or working life? Could this be relevant? Stress rarely causes rheumatic disease but may precipitate a flare-up of inflammatory arthritis. It reduces a person’s ability to cope with pain or disability.

Has there been an injury for which a legal case for compensation is pending?

Has there been an injury for which a legal case for compensation is pending?

The World Health Organization describes the impact of disease on an individual in terms of:

Impairment: any loss or abnormality of psychological or anatomical structure or function

Impairment: any loss or abnormality of psychological or anatomical structure or function

Disability (activity limitation): any restriction or lack of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being

Disability (activity limitation): any restriction or lack of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being

Handicap (participation restriction): a disadvantage for an individual resulting from an impairment or disability that limits or prevents the fulfilment of a role that is normal for that individual.

Handicap (participation restriction): a disadvantage for an individual resulting from an impairment or disability that limits or prevents the fulfilment of a role that is normal for that individual.

Examination of the joints

Always observe a patient, looking for disabilities, as he or she walks into the room and sits down. General and neurological examinations are often necessary. Guidelines for rapid examinations of the limbs and spine are shown in Practical Box 11.1.

![]() Practical Box 11.1

Practical Box 11.1

Rapid examinations of the limb and spine

Rapid examination of the upper limbs

Raise arms sideways to the ears (abduction). Reach behind neck and back. Difficulties with these movements indicate a shoulder or rotator cuff problem.

Raise arms sideways to the ears (abduction). Reach behind neck and back. Difficulties with these movements indicate a shoulder or rotator cuff problem.

Hold the arms forward, with elbows straight and fingers apart, palm up and palm down. Fixed flexion at the elbow indicates an elbow problem. Examine the hands for swelling, wasting and deformity.

Hold the arms forward, with elbows straight and fingers apart, palm up and palm down. Fixed flexion at the elbow indicates an elbow problem. Examine the hands for swelling, wasting and deformity.

Place the hands in the ‘prayer’ position with the elbows apart. Flexion deformities of the fingers may be due to arthritis, flexor tenosynovitis or skin disease. Painful restriction of the wrist limits the person’s ability to move the elbows out with the hands held together.

Place the hands in the ‘prayer’ position with the elbows apart. Flexion deformities of the fingers may be due to arthritis, flexor tenosynovitis or skin disease. Painful restriction of the wrist limits the person’s ability to move the elbows out with the hands held together.

Make a tight fist. Difficulty with this indicates a loss of flexion or grip. Grip strength can be measured.

Make a tight fist. Difficulty with this indicates a loss of flexion or grip. Grip strength can be measured.

Rapid examination of the lower limbs

Ask the patient to walk a short distance away from and towards you, and to stand still. Look for abnormal posture or stance.

Ask the patient to walk a short distance away from and towards you, and to stand still. Look for abnormal posture or stance.

Ask the patient to stand on each leg. Severe hip disease causes the pelvis on the non-weight-bearing side to sag (positive Trendelenburg test).

Ask the patient to stand on each leg. Severe hip disease causes the pelvis on the non-weight-bearing side to sag (positive Trendelenburg test).

Watch the patient stand and sit, looking for hip and/or knee problems.

Watch the patient stand and sit, looking for hip and/or knee problems.

Ask the patient to straighten and flex each knee.

Ask the patient to straighten and flex each knee.

Ask the patient to place each foot in turn on the opposite knee with the hip externally rotated. This tests for painful restriction of hip or knee. Abnormal hips or knees must be examined lying.

Ask the patient to place each foot in turn on the opposite knee with the hip externally rotated. This tests for painful restriction of hip or knee. Abnormal hips or knees must be examined lying.

Move each ankle up and down. Examine the ankle joint and tendons, medial arch and toes whilst standing.

Move each ankle up and down. Examine the ankle joint and tendons, medial arch and toes whilst standing.

Rapid examination of the spine

Ask the patient to (a) bend forwards to touch the toes with straight knees, (b) extend backwards, (c) flex sideways, and (d) look over each shoulder, flexing and extending and sideflexing the neck. Observe abnormal spinal curves – scoliosis (lateral curve), kyphosis (forward bending) or lordosis (backward bending). A cervical and lumbar lordosis and a thoracic kyphosis are normal. Muscle spasm is worse whilst standing and bending. Leg length inequality leads to a scoliosis which decreases on sitting or lying (the lengths are measured lying).

Ask the patient to (a) bend forwards to touch the toes with straight knees, (b) extend backwards, (c) flex sideways, and (d) look over each shoulder, flexing and extending and sideflexing the neck. Observe abnormal spinal curves – scoliosis (lateral curve), kyphosis (forward bending) or lordosis (backward bending). A cervical and lumbar lordosis and a thoracic kyphosis are normal. Muscle spasm is worse whilst standing and bending. Leg length inequality leads to a scoliosis which decreases on sitting or lying (the lengths are measured lying).

Ask the patient to lie supine. Examine any restriction of straight-leg raising (see disc prolapse, below).

Ask the patient to lie supine. Examine any restriction of straight-leg raising (see disc prolapse, below).

Ask the patient to lie prone. Examine for anterior thigh pain during a femoral stretch test (flexing knee whilst prone), which indicates a high lumbar disc problem.

Ask the patient to lie prone. Examine for anterior thigh pain during a femoral stretch test (flexing knee whilst prone), which indicates a high lumbar disc problem.

Examining an individual joint involves three stages: looking, feeling and moving (Table 11.1). A screening examination of the locomotor system, known by the acronym GALS (Global Assessment of the Locomotor System) has been devised. X-ray or ultrasound of the joint often forms an integral part of the examination.

|

LOOK at the appearance of the joint |

Swelling – could be bony, fluid or synovial |

|

Deformity – valgus, where the distal bone is deviated laterally (e.g. knock-knees or genu valgum) |

|

|

Varus where the distal bone is deviated medially (bow-legs or genu varum) |

|

|

Fixed flexion or hyperextension |

|

|

Rash – especially psoriasis |

|

|

Muscle wasting – easier to see in large muscles like the quadriceps |

|

|

Scars – from surgery or trauma |

|

|

Signs of inflammationSymmetry – are the right and left joints (e.g. hips, knees, any other paired joint) the same? If not which do you think is abnormal? |

|

|

FEEL |

Swelling – fluid swelling (effusion) usually represents increased synovial fluid in inflammatory arthritis, but can be due to blood or pus |

|

Synovial swelling is rubbery or boggy and usually occurs in inflammatory arthritis |

|

|

Bony swelling, such as Heberden’s nodes in the fingers is usually seen in osteoarthritis |

|

|

Warmth – a warm joint may be inflamed or infected |

|

|

Tenderness – may represent joint inflammation, but many people have chronic tenderness all over the body (e.g. in fibromyalgia) |

|

|

MOVE |

Active movement – is the range full and pain-free? Is the movement fluid? In the hands – can the patient perform fine movements? In the legs – can the patient walk properly? |

|

Compare movements on the right and left side – are they symmetrical? |

|

|

Is there crepitus when the joint is moved? |

|

|

If active movement is limited try passive movement. In a joint problem both will usually be affected. If it is a muscle or nerve problem passive movement may remain full. |

Investigations

Useful blood screening tests

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). An increase of these reflects inflammation. Plasma viscosity is also raised in inflammatory disease.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). An increase of these reflects inflammation. Plasma viscosity is also raised in inflammatory disease.

Bone and liver biochemistry. A raised serum alkaline phosphatase may indicate liver or bone disease. A rise in liver enzymes is seen with drug-induced toxicity. For other investigations of bone, see page 550.

Bone and liver biochemistry. A raised serum alkaline phosphatase may indicate liver or bone disease. A rise in liver enzymes is seen with drug-induced toxicity. For other investigations of bone, see page 550.

Serum autoantibody studies

Rheumatoid factors (RFs) (see also p. 518). Rheumatoid factors are detected by enzyme linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA). RFs are antibodies (usually IgM, but also IgG or IgA) against the Fc portion of IgG. They are detected in 70% of people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), but are not diagnostic. RFs are detected in many autoimmune rheumatic disorders (e.g. SLE), in chronic infections, and in asymptomatic older people (Table 11.2).

Rheumatoid factors (RFs) (see also p. 518). Rheumatoid factors are detected by enzyme linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA). RFs are antibodies (usually IgM, but also IgG or IgA) against the Fc portion of IgG. They are detected in 70% of people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), but are not diagnostic. RFs are detected in many autoimmune rheumatic disorders (e.g. SLE), in chronic infections, and in asymptomatic older people (Table 11.2).

Anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA). These antibodies are directed against citrullinated antigens, vimentin, fibrinogen, alpha enolase and type II collagen. They are measured by an ELISA technique and are present in up to 80% of people with RA. They have a high specificity for RA (90% with a sensitivity of 60%). They are helpful in early disease when the RF is negative to distinguish it from acute transient synovitis (see Box 11.6, p. 519). Positivity for RF and/or ACPA is associated with a worse prognosis and an increase in the likelihood of bony erosions in people with RA.

Anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA). These antibodies are directed against citrullinated antigens, vimentin, fibrinogen, alpha enolase and type II collagen. They are measured by an ELISA technique and are present in up to 80% of people with RA. They have a high specificity for RA (90% with a sensitivity of 60%). They are helpful in early disease when the RF is negative to distinguish it from acute transient synovitis (see Box 11.6, p. 519). Positivity for RF and/or ACPA is associated with a worse prognosis and an increase in the likelihood of bony erosions in people with RA.

Antinuclear antibodies (ANAs). These are detected by indirect immunofluorescent staining of fresh-frozen sections of rat liver or kidney or Hep-2 cell lines. Different patterns reflect a variety of antigenic specificities that occur with different clinical pictures (see Box 11.16, p. 537). ANA is used as a screening test for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and systemic sclerosis (SSc) – a negative ANA makes either condition highly unlikely – but low titres occur in RA and chronic infections and in normal individuals, especially the elderly (Table 11.3).

Antinuclear antibodies (ANAs). These are detected by indirect immunofluorescent staining of fresh-frozen sections of rat liver or kidney or Hep-2 cell lines. Different patterns reflect a variety of antigenic specificities that occur with different clinical pictures (see Box 11.16, p. 537). ANA is used as a screening test for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and systemic sclerosis (SSc) – a negative ANA makes either condition highly unlikely – but low titres occur in RA and chronic infections and in normal individuals, especially the elderly (Table 11.3).

Anti-double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies. These are usually detected by a precipitation test (Farr assay), by ELISA, or by an immunofluorescent test using Crithidia luciliae (which contains double-stranded DNA). Raised anti-dsDNA is highly specific for SLE and the levels usually rise and fall in parallel with disease activity so can be used to monitor the level of treatment required.

Anti-double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies. These are usually detected by a precipitation test (Farr assay), by ELISA, or by an immunofluorescent test using Crithidia luciliae (which contains double-stranded DNA). Raised anti-dsDNA is highly specific for SLE and the levels usually rise and fall in parallel with disease activity so can be used to monitor the level of treatment required.

Anti-extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) antibodies (see Box 11.16, p. 537). These produce a speckled ANA fluorescent pattern, and can be identified by ELISA. The most commonly measured ENAs are:

Anti-extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) antibodies (see Box 11.16, p. 537). These produce a speckled ANA fluorescent pattern, and can be identified by ELISA. The most commonly measured ENAs are:

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) (see p. 544). These are predominantly IgG autoantibodies directed against the primary granules of neutrophil and macrophage lysosomes. They are strongly associated with small-vessel vasculitis. Two major clinically relevant ANCA patterns are recognized on immunofluorescence:

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) (see p. 544). These are predominantly IgG autoantibodies directed against the primary granules of neutrophil and macrophage lysosomes. They are strongly associated with small-vessel vasculitis. Two major clinically relevant ANCA patterns are recognized on immunofluorescence:

Antiphospholipid antibodies (see p. 538). These are detected in the antiphospholipid syndrome (see p. 538).

Antiphospholipid antibodies (see p. 538). These are detected in the antiphospholipid syndrome (see p. 538).

Immune complexes. Immune complexes are infrequently measured, largely because of variability between assays and difficulty in interpreting their meaning. Assays based on the polyethylene glycol precipitation method (PEG) or C1q binding are available commercially.

Immune complexes. Immune complexes are infrequently measured, largely because of variability between assays and difficulty in interpreting their meaning. Assays based on the polyethylene glycol precipitation method (PEG) or C1q binding are available commercially.

Complement. Low complement levels indicate consumption and suggest an active disease process in SLE.

Complement. Low complement levels indicate consumption and suggest an active disease process in SLE.

Table 11.2 Conditions in which rheumatoid factor is found in the serum

|

Autoimmune rheumatic diseases |

RF (IgM) % |

|

Rheumatoid arthritis |

70 |

|

Systemic lupus erythematosus |

25 |

|

Sjögren’s syndrome |

90 |

|

Systemic sclerosis |

30 |

|

Polymyositis/dermatomyositis |

50 |

|

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis |

Variable |

|

Viral infections |

Hyperglobulinaemias |

|

Hepatitis |

Chronic liver disease |

|

Infectious mononucleosis |

Sarcoidosis |

|

Cryoglobulinaemia |

|

|

Chronic infections |

Normal population |

|

Tuberculosis |

Elderly |

|

Leprosy |

Relatives of people with RA |

|

Syphilis |

|

Table 11.3 Conditions in which serum antinuclear antibodies are found

| (%) | |

|---|---|

|

Systemic lupus erythematosus |

95 |

|

Systemic sclerosis |

70 |

|

Sjögren’s syndrome |

80 |

|

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis |

40 |

|

Rheumatoid arthritis |

30 |

|

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis |

Variable |

|

Other diseases |

|

|

Autoimmune hepatitis |

100 |

|

Drug-induced lupus |

>95 |

|

Myasthenia gravis |

50 |

|

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

30 |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

25 |

|

Infectious mononucleosis |

5–10 |

|

Normal population |

8 |

Joint aspiration

Examination of joint (or bursa) fluid is used mainly to diagnose septic, reactive or crystal arthritis. The appearance of the fluid is an indicator of the level of inflammation. The procedure is often undertaken in combination with injection of a corticosteroid. Aspiration alone is therapeutic in crystal arthritis (see Practical Box 11.2, p. 508).

Examination of synovial fluid

Diagnostic imaging and visualization

X-rays can be diagnostic in certain conditions (e.g. established rheumatoid arthritis) and are the first investigation in many cases of trauma. X-rays can detect joint space narrowing, erosions in rheumatoid arthritis, calcification in soft tissue, new bone formation, e.g. osteophytes and decreased bone density (osteopenia) or increased bone density (osteosclerosis):

X-rays can be diagnostic in certain conditions (e.g. established rheumatoid arthritis) and are the first investigation in many cases of trauma. X-rays can detect joint space narrowing, erosions in rheumatoid arthritis, calcification in soft tissue, new bone formation, e.g. osteophytes and decreased bone density (osteopenia) or increased bone density (osteosclerosis):

Ultrasound (US) is particularly useful for periarticular structures, soft tissue swellings and tendons and for detecting active synovitis in inflammatory arthritis. It is increasingly used to examine the shoulder and other structures during movement, e.g. shoulder impingement syndrome (see p. 500). Doppler US measures blood flow and hence inflammation. US is used to guide local injections.

Ultrasound (US) is particularly useful for periarticular structures, soft tissue swellings and tendons and for detecting active synovitis in inflammatory arthritis. It is increasingly used to examine the shoulder and other structures during movement, e.g. shoulder impingement syndrome (see p. 500). Doppler US measures blood flow and hence inflammation. US is used to guide local injections.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows bone changes and intra-articular structures in striking detail. Visualization of particular structures can be enhanced with different resonance sequences. T1-weighted is used for anatomical detail, T2-weighted for fluid detection and short tau inversion recovery (STIR) for the presence of bone marrow oedema. It is more sensitive than X-rays in the early detection of articular and periarticular disease. It is the investigation of choice for most spinal disorders but is inappropriate in uncomplicated mechanical low back pain. Gadolinium injection enhances inflamed tissue. MRI can also detect muscle changes, e.g. myositis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows bone changes and intra-articular structures in striking detail. Visualization of particular structures can be enhanced with different resonance sequences. T1-weighted is used for anatomical detail, T2-weighted for fluid detection and short tau inversion recovery (STIR) for the presence of bone marrow oedema. It is more sensitive than X-rays in the early detection of articular and periarticular disease. It is the investigation of choice for most spinal disorders but is inappropriate in uncomplicated mechanical low back pain. Gadolinium injection enhances inflamed tissue. MRI can also detect muscle changes, e.g. myositis.

Computerized axial tomography (CT) is useful for detecting changes in calcified structures but dose of irradiation is high.

Computerized axial tomography (CT) is useful for detecting changes in calcified structures but dose of irradiation is high.

Bone scintigraphy utilizes radionuclides, usually 99mTc, and detects abnormal bone turnover and blood circulation and, although nonspecific, helps in detecting areas of inflammation, infection or malignancy. It is best used in combination with other anatomical imaging techniques.

Bone scintigraphy utilizes radionuclides, usually 99mTc, and detects abnormal bone turnover and blood circulation and, although nonspecific, helps in detecting areas of inflammation, infection or malignancy. It is best used in combination with other anatomical imaging techniques.

DXA scanning uses very low doses of X-irradiation to measure bone density and is used in the screening and monitoring of osteoporosis.

DXA scanning uses very low doses of X-irradiation to measure bone density and is used in the screening and monitoring of osteoporosis.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning uses radionuclides, which decay by emission of positrons. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake indicates areas of increased glucose metabolism. It is used to locate tumours and demonstrate large vessel vasculitis, e.g. Takayasu’s arteritis (see p. 789). PET scans are combined with CT to improve anatomical details.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning uses radionuclides, which decay by emission of positrons. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake indicates areas of increased glucose metabolism. It is used to locate tumours and demonstrate large vessel vasculitis, e.g. Takayasu’s arteritis (see p. 789). PET scans are combined with CT to improve anatomical details.

Arthroscopy is a direct means of visualizing a joint, particularly the knee or shoulder. Biopsies can be taken, surgery performed in certain conditions (e.g. repair or trimming of meniscal tears), and loose bodies removed.

Arthroscopy is a direct means of visualizing a joint, particularly the knee or shoulder. Biopsies can be taken, surgery performed in certain conditions (e.g. repair or trimming of meniscal tears), and loose bodies removed.

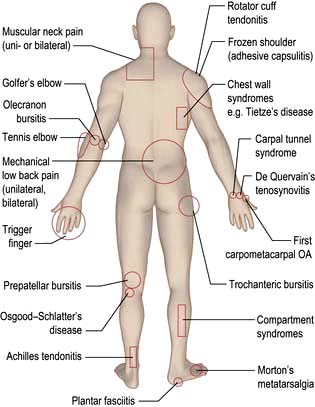

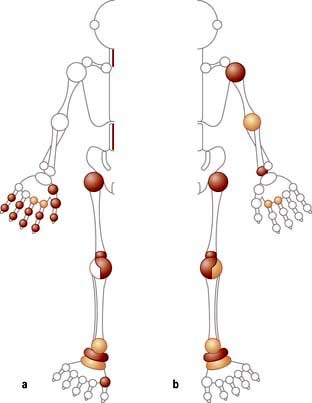

Common regional musculoskeletal problems (fig. 11.2)

Pain in the neck and shoulder (Table 11.4)

Mechanical or muscular neck pain (shoulder girdle pain)

Spondylosis seen on X-ray increases after the age of 40 years, but it is not always causal. Spondylosis can, however, cause stiffness and increases the risk of mechanical or muscular neck pain. Muscle spasm is palpable and tender and may lead to abnormal neck posture (e.g. acute torticollis). Muscular-pattern neck pain is not localized but affects the trapezius muscle, the C7 spinous process and the paracervical musculature (shoulder girdle pain). Pain often radiates upwards to the occiput and is commonly associated with tension headaches. These features are also seen in chronic widespread pain (see p. 509).

Treatment

Patients are given short courses of analgesic therapy along with reassurance and explanation. Physiotherapists can help to relieve spasm and pain, teach exercises and relaxation techniques, and improve posture. An occupational therapist can advise about the ergonomics of the workplace if the problem is work-related (see p. 510).

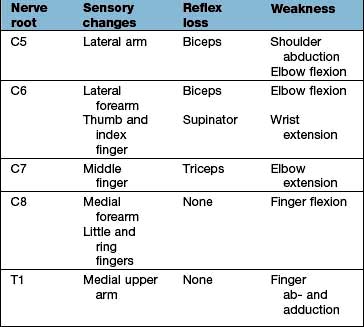

Nerve root entrapment

Acute cervical disc prolapse presents with unilateral pain in the neck, radiating to the interscapular and shoulder regions. This diffuse, aching dural pain is followed by sharp, electric shock-like pain down the arm, in a nerve root distribution, often with pins and needles, numbness, weakness and loss of reflexes (Table 11.5).

Cervical spondylosis occurs in the older patient with posterolateral osteophytes compressing the nerve root and causing root pain (see Fig. 22.58, p. 1148), commonly at C5/C6 or C6/C7; it is seen on oblique radiographs of the neck. An MRI scan clearly distinguishes facet joint OA, root canal narrowing and disc prolapse.

Treatment

A support collar, rest, analgesia and sedation are used initially as necessary. Patients should be advised not to carry heavy items. It usually recovers in 6–12 weeks. MRI is the investigation of choice if surgery is being considered or the diagnosis is uncertain (Fig. 11.3). A cervical root block administered under direct vision by an experienced pain specialist may relieve pain while the disc recovers. Neurosurgical referral is essential if the pain persists or if the neurological signs of weakness or numbness are severe or bilateral. Bilateral root pain with or without long track symptoms or signs is a neurosurgical emergency because a central disc prolapse may compress the cervical spinal cord. Posterior osteophytes may cause spinal claudication and cervical myelopathy.

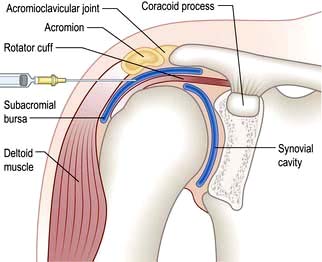

Pain in the shoulder

The shoulder is a shallow joint with a large range of movement. The humeral head is held in place by the rotator cuff (Fig. 11.4) which is part of the joint capsule. It comprises the tendons of infraspinatus and teres minor posteriorly, supraspinatus superiorly and teres major and subscapularis anteriorly. The rotator cuff (particularly supraspinatus) prevents the humeral head blocking against the acromion during abduction; the deltoid pulls up and the supraspinatus pulls in to produce a turning movement and the greater tuberosity glides under the acromion without impingement. Shoulder pathology restricts or is made worse by shoulder movement. Specific diagnoses are difficult to make clinically but this may not matter for pain management.

Pain in the shoulder can sometimes be due to problems in the neck. The differential diagnosis of this is shown in Box 11.1. Adhesive capsulitis (true frozen shoulder) is uncommon (see below). Early inflammatory arthritis and polymyalgia rheumatica in the elderly may present with shoulder pain. Shoulder pain is more common in diabetic patients than in the general population.

![]() Box 11.1

Box 11.1

Differential diagnosis of ‘shoulder’ pain

Rotator cuff tendonitis pain is worse at night and radiates to the upper arm.

Rotator cuff tendonitis pain is worse at night and radiates to the upper arm.

Painful shoulders produce secondary muscular neck pain.

Painful shoulders produce secondary muscular neck pain.

Muscular neck pain (also known as shoulder girdle pain) does not radiate to the upper arm.

Muscular neck pain (also known as shoulder girdle pain) does not radiate to the upper arm.

Cervical nerve root pain is usually associated with pins and needles or neurological signs in the arm.

Cervical nerve root pain is usually associated with pins and needles or neurological signs in the arm.

Rotator cuff (supraspinatus) tendonosis

Treatment

Analgesics, NSAIDs and/or physiotherapy may suffice, but severe pain responds to an injection of corticosteroid into the subacromial bursa (Fig. 11.4). Patients should be warned that 10% will develop worse pain for 24–48 hours after injection. Some 70% improve over 5–20 days and mobilize the joint themselves. Physiotherapy helps persistent stiffness. Further ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injections may be needed but the long-term benefit is unclear.

Pain in the elbow

Epicondylitis

Treatment

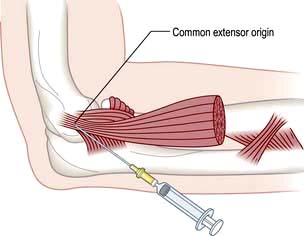

Advise rest and arrange review by a physiotherapist. A local injection of corticosteroid at the point of maximum tenderness is helpful when the pain is severe but needs physiotherapy follow-up to prevent recurrences (Fig. 11.5). Avoid the ulnar nerve when injecting golfer’s elbow. Both conditions settle spontaneously eventually, but occasionally persist and require surgical release.

Pain in the hand and wrist (table 11.6)

| All ages | Older patients |

|---|---|

|

Trauma/fractures |

Nodal OA: |

|

Tenosynovitis: |

DIPs (Heberden’s nodes) |

|

Flexor with/without triggering |

PIPs (Bouchard’s nodes) |

|

Dorsal |

|

|

De Quervain’s |

Trauma – scaphoid fracture |

|

Pseudogout |

|

|

Gout: |

|

|

Acute |

|

|

Tophaceous |

|

|

|

DIPs, PIPs, distal and proximal interphalangeal joints.

Carpal tunnel syndrome

This is due to median nerve compression in the limited space of the carpal tunnel. Thickened ligaments, tendon sheaths or bone enlargement can cause it, but it is usually idiopathic. (Causes are discussed on p. 1144.) The history is usually typical and diagnostic with the patient waking with numbness, tingling and pain in a median nerve distribution. The pain radiates to the forearm. The fingers feel swollen but usually are not. Wasting of the abductor pollicis brevis develops with sensory loss in the radial three and a half fingers. The pain may be produced by tapping the nerve in the carpal tunnel (Tinel’s sign) or by holding the wrist in flexion (Phalen’s test).

Other conditions causing pain

Nodal osteoarthritis. This affects the DIP and less commonly PIP joints, which are initially swollen and red. The inflammation and pain settle but bony swellings remain (p. 514).

Pain in the lower back

Low back pain is a common symptom. It is often traumatic and work-related, although lifting apparatus and other mechanical devices and improved office seating help to avoid it. Episodes are generally short-lived and self-limiting, and patients attend a physiotherapist or osteopath more often than a doctor. Chronic back pain is the cause of 14% of long-term disability in the UK. The causes are listed in Table 11.7, and the management of back pain is summarized in Box 11.2.

|

Mechanical |

|

Inflammatory |

|

Metabolic |

|

Neoplastic (see p. 589) |

Referred pain

![]() Box 11.2

Box 11.2

Management of back pain

Most back pain presenting to a primary care physician needs no investigation.

Most back pain presenting to a primary care physician needs no investigation.

Pain between the ages of 20 and 55 years is likely to be mechanical and is managed with analgesia, brief rest if necessary and physiotherapy.

Pain between the ages of 20 and 55 years is likely to be mechanical and is managed with analgesia, brief rest if necessary and physiotherapy.

Patients should stay active within the limits of their pain.

Patients should stay active within the limits of their pain.

Early treatment of the acute episode, advice and exercise programmes reduce long-term problems and prevent chronic pain syndromes.

Early treatment of the acute episode, advice and exercise programmes reduce long-term problems and prevent chronic pain syndromes.

Physical manipulation of uncomplicated back pain produces short-term relief and enjoys high patient satisfaction ratings.

Physical manipulation of uncomplicated back pain produces short-term relief and enjoys high patient satisfaction ratings.

Psychological and social factors may influence the time of presentation.

Psychological and social factors may influence the time of presentation.

Investigations

Spinal X-rays are required only if the pain is associated with certain ‘red flag’ symptoms or signs, which indicate a high risk of more serious underlying problems:

Spinal X-rays are required only if the pain is associated with certain ‘red flag’ symptoms or signs, which indicate a high risk of more serious underlying problems:

MRI is preferable to CT scanning when neurological signs and symptoms are present. CT scans demonstrate bony pathology better. Interpretation of the relevance of the findings may require a specialist opinion.

MRI is preferable to CT scanning when neurological signs and symptoms are present. CT scans demonstrate bony pathology better. Interpretation of the relevance of the findings may require a specialist opinion.

Bone scans are useful in infective and malignant lesions but are also positive in degenerative lesions.

Bone scans are useful in infective and malignant lesions but are also positive in degenerative lesions.

Full blood count, ESR and biochemical tests are required only when the pain is likely to be due to malignancy, infection or a metabolic cause. Normal ESR and CRP distinguish mechanical back pain from polymyalgia rheumatica, a likely differential in the elderly.

Full blood count, ESR and biochemical tests are required only when the pain is likely to be due to malignancy, infection or a metabolic cause. Normal ESR and CRP distinguish mechanical back pain from polymyalgia rheumatica, a likely differential in the elderly.

Mechanical low back pain

Examination and management

pre-existing chronic widespread pain (fibromyalgia)

pre-existing chronic widespread pain (fibromyalgia)

psychosocial factors such as high levels of psychological distress, poor self-rated health and dissatisfaction with employment.

psychosocial factors such as high levels of psychological distress, poor self-rated health and dissatisfaction with employment.

Spinal movement occurs at the disc and the posterior facet joints, and stability is normally achieved by a complex mechanism of spinal ligaments and muscles. Any of these structures may be a source of pain. An exact anatomical diagnosis is difficult, but some typical syndromes are recognized (see below). They are often associated with but not necessarily caused by radiological spondylosis (see p.1148).

Postural back pain develops in individuals who sit in poorly designed, unsupportive chairs.

Reactive changes develop in adjacent vertebrae; the bone becomes sclerotic and osteophytes form around the rim of the vertebra (Fig. 11.6). The most common sites of lumbar spondylosis are L5/S1 and L4/L5.

Acute lumbar disc prolapse

The central disc gel may extrude into a fissure in the surrounding fibrous zone and cause acute pain and muscle spasm. These events are often self-limiting. A disc prolapse occurs when the extrusion extends beyond the limits of the fibrous zone (Fig. 11.6). The weakest point is posterolateral, where the disc may impinge on emerging spinal nerve roots in the root canal.

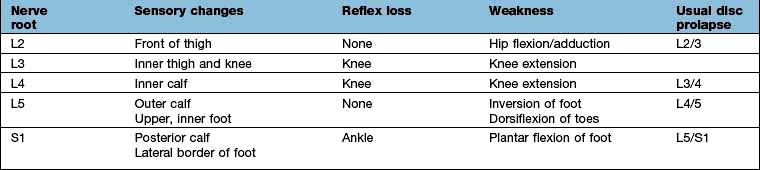

The episode often starts dramatically during lifting, twisting or bending and produces a typical combination of low back pain and muscle spasm, and severe, lancinating pains, paraesthesia, numbness and neurological signs in one leg (rarely both). The back pain is diffuse, usually unilateral and radiates into the buttock. The muscle spasm leads to a scoliosis that reduces when lying down. The nerve root pain develops with, or soon after, the onset. The site of the pain and other symptoms is determined by the root affected (Table 11.8). A central high lumbar disc prolapse may cause spinal cord compression and long tract signs (i.e. upper motor neurone). Below L2/L3 it produces lower motor neurone lesions.

On examination, the back often shows a marked scoliosis and muscle spasm. The straight-leg-raising test, whilst lying, is positive in a lower lumbar disc prolapse – raising the straight leg beyond 30° produces pain in the leg. Slight limitation or pain in the back limiting this movement is seen with mechanical back pain. Pain in the affected leg produced by a straight raise of the other leg suggests a large or central disc prolapse. Look for perianal sensory loss and urinary retention, which indicate a cauda equina lesion – a neurosurgical emergency (see p. 1135). An upper lumbar disc prolapse produces a positive femoral stretch test; pain in the anterior thigh when the knee is flexed in the prone position.

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH)

DISH (Forestier’s disease) affects the spine and extraspinal locations. It causes bony overgrowths and ligamentous ossification and is characterized by flowing calcification over the anterolateral aspects of the vertebrae. The spine is stiff but not always painful, despite the dramatic X-ray changes. Ossification at muscle insertions around the pelvis produces radiological ‘whiskering’. Similar changes occur at the patella and in the feet. It is commoner in people with metabolic syndrome (high BMI, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidaemia; see p. 1006).

Pain in the hip (table 11.9)

| Hip region problems | Main sites of pain |

|---|---|

|

Osteoarthritis of hip |

Groin, buttock, front of thigh to knee |

|

Trochanteric bursitis (or gluteus medius tendonopathy) |

Lateral thigh to knee |

|

Meralgia paraesthetica |

Anterolateral thigh to knee |

|

Referred from back |

Buttock |

|

Facet joint pain |

Buttock and posterior thigh |

|

Fracture of neck of femur |

Groin and buttock |

|

Inflammatory arthritis |

Groin, buttock, front of thigh to knee |

|

Sacroiliitis (AS) |

Buttock(s) |

|

Avascular necrosis |

Groin and buttocks |

|

Polymyalgia rheumatica |

Lumbar spine, buttocks and thighs |

AS, ankylosing spondylitis.

Osteoarthritis (OA)

OA (see p. 512) is the most common cause of hip joint pain in a person over the age of 50 years. It causes pain in the buttock and groin on standing and walking. Stiff hip movements cause difficulty in putting on a sock and may produce a limp. Sudden onset pain may be associated with an effusion on MRI and can be treated by an ultrasound guided steroid injection.

Fracture of the femoral neck

This usually occurs after a fall, occasionally spontaneously. There is pain in the groin and thigh, weight-bearing is painful or impossible, and the leg is shortened and externally rotated. Occasionally, a fracture is not displaced and remains undetected. X-rays are diagnostic. Anyone with a hip fracture, especially after minimal trauma, should be reviewed for osteoporosis (see p. 553).

Avascular necrosis (osteonecrosis) of the femoral head

This is uncommon but occurs at any age. (Risk factors are discussed on p. 556.) There is severe hip pain. X-rays are diagnostic after a few weeks, when a well-demarcated area of increased bone density is visible at the upper pole of the femoral head. The affected bone may collapse. Early, the X-ray is normal but bone scintigraphy or MRI demonstrates the lesion and shows bone marrow oedema.

Pain in the knee (table 11.10)

|

Trauma and overuse |

|

Periarticular problems |

Osteoarthritis/Inflammatory arthritis

Other

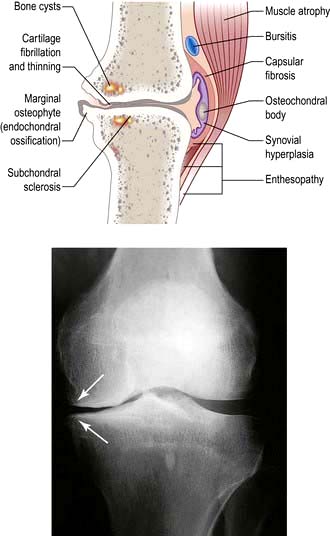

The knee is also a common site of inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Minor radiographic changes of osteoarthritis (see Fig. 11.11) are common in the over-50s and often coincidental, the cause of the pain being periarticular. Symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee correlates poorly with the severity of the radiological changes.

Common periarticular knee lesions

Anterior knee pain is common in adolescence. In many cases, no specific cause is found, despite investigation. This is called ‘anterior knee pain syndrome’ and settles with time. Isometric quadriceps exercises and avoidance of high heels both help the condition. Patient and parents often need firm reassurance. Abnormal patellar tracking may be a cause and need surgical treatment. Hypermobility of joints causes joint pain, maltracking and rarely recurrent patellar dislocation (see also p. 546).

Osgood–Schlatter disease (p. 546) causes pain and swelling over the tibial tubercle. It is a traction apophysitis of the patellar tendon and occurs in enthusiastic teenage sports players.

Enthesitis may occur at the patellar end of the tendon (jumper’s knee).

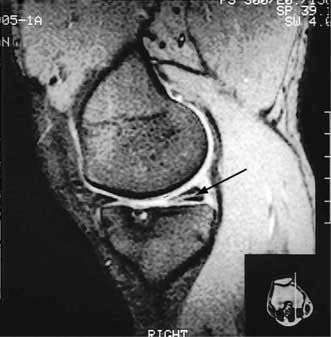

Common intra-articular traumatic lesions of the knee

The menisci are partially attached fibrocartilages that stabilize the rounded femoral condyles on the flat tibial plateaux. In the young they are resilient but this decreases with age. They can be torn by an injury, commonly in sports that involve twisting and bending. The history is usually diagnostic. There is immediate medial or lateral knee pain and swelling within a few hours. The affected side is tender. If the tear is large the knee may lock flexed. The immediate treatment is to apply ice. MRI demonstrates the tear (Fig. 11.7). In most circumstances, especially in active sportsmen, early arthroscopic repair or trimming of the torn meniscus is essential. Surgical intervention reduces recurrent pain, swelling and locking but not the risk of secondary osteoarthritis. The long-term benefit of early repair of tears is not yet known. Post-surgical quadriceps exercises aid a return to sport and other activities.

Knee joint effusions

Monoarthritis of the knee, associated with severe pain and marked redness, may be due to septic arthritis, or gout in the middle-aged male, or to gout or pseudogout in an older male or female. A cool, clear, viscous effusion is seen in elderly people with moderate or severe symptomatic OA (see p. 512).

Investigations

These are (a) blood tests, and (b) aspiration (Fig. 11.8) and examination of the knee effusion. The basic technique of aspiration is described in Practical Box 11.2.

![]() Practical Box 11.2 Joint aspiration

Practical Box 11.2 Joint aspiration

This is a sterile procedure which should be carried out in a clean environment

Explain the procedure to the patient; obtain consent.

1. Decide on the site to insert the needle and mark it.

2. Clean the skin and your hands scrupulously; remove rings and wristwatch. Put on gloves.

3. Draw up local anaesthetic (and corticosteroid if it is being used) and then use a new needle.

4. Warn the patient, insert the needle, injecting local anaesthetic as it advances and, if a joint effusion is suspected, attempt to aspirate as you advance it.

5. If fluid is obtained, change syringes and aspirate fully.

6. Examine the fluid in the syringe and decide whether or not to proceed with a corticosteroid injection (if fluid clear or slightly cloudy) or send for microbiological tests.

7. Cover the injection site and advise the patient to rest the affected area for a few days. Warn the patient that the pain may increase initially but to report urgently if this persists beyond a few days, if the swelling worsens, or if they become febrile, since this might indicate an infected joint.

Trauma: meniscal, cruciate or synovial lining tear

Trauma: meniscal, cruciate or synovial lining tear

Clotting or bleeding disorders: such as haemophilia, sickle cell disease or von Willebrand’s disease.

Clotting or bleeding disorders: such as haemophilia, sickle cell disease or von Willebrand’s disease.

A history of previous knee problems and the sudden onset of pain and tenderness high in the calf suggest a ruptured cyst rather than a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). However, the diagnosis is often missed and treated inappropriately with anticoagulants. A diagnostic ultrasound examination distinguishes a ruptured cyst from a DVT (see p. 789). Analgesics or NSAIDs, rest with the leg elevated, and aspiration and injection with corticosteroids into the knee joint are required.

Pain in the foot and heel (table 11.11)

|

Structural (flat (pronated) or high arched (supinated)) |

|

|

Hallux valgus/rigidus (±OA) |

|

|

Metatarsalgia |

|

|

Morton’s neuroma |

|

|

Stress fracture |

|

|

Inflammatory arthritis |

|

|

Acute, monoarticular – gout |

|

|

Chronic, polyarticular – RA |

|

|

Chronic, pauciarticular – spondyloarthritis |

|

|

Tarsal tunnel syndrome |

|

|

Heel pain |

|

|

Plantar fasciitis |

Below heel |

|

Plantar spur |

Below heel |

|

Achilles tendonitis/bursitis |

Behind heel |

|

Sever’s disease |

Behind heel |

|

Arthritis of ankle/subtaloid joints |

|

There are two common types of foot deformity:

Flat feet: stress the ankle and throw the hindfoot into a valgus (everted) position. A flat foot is rigid and inflexible.

Flat feet: stress the ankle and throw the hindfoot into a valgus (everted) position. A flat foot is rigid and inflexible.

High-arched feet: place pressure on the lateral border and ball of the foot.

High-arched feet: place pressure on the lateral border and ball of the foot.

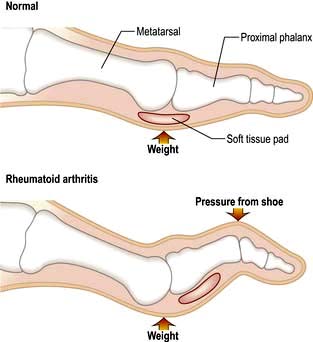

The foot is affected by a variety of inflammatory arthritic conditions. After the hand, the foot joints are the most commonly affected by rheumatoid arthritis. The diagnosis depends upon careful assessment of the distribution of the joints affected, the pattern of other joint problems or by finding the associated condition (e.g. psoriasis, see p. 1207).

Pain in the chest

Musculoskeletal conditions are sometimes a cause of chest pain. An example is Tietze’s disease. In this condition, pain arises from the costosternal junctions. It is usually unilateral and affects one, two or three ribs. There is local tenderness, which helps to make the diagnosis. The condition is benign and self-limiting. It often responds well to anti-inflammatory drugs. Other causes of chest wall pain include rib fractures due to trauma or osteoporosis or a malignant deposit. Costochondral pain occurs in ankylosing spondylitis (see p. 527). In people with heart disease, costochondral pain may cause severe anxiety but it is not like angina and the patient should be reassured.

Chronic pain syndromes

Chronic pain syndromes (see p. 1163) are difficult to manage. Psychological factors are at least as relevant as inflammation or damage in determining the patient’s perception of pain. It is essential to be objective and non-judgemental when discussing physical, psychological and social factors without assuming which is primary. Chronic pain syndromes are difficult to explain scientifically. It is all too easy for a doctor to respond to this lack of a clear scientific cause by seeming to ‘blame’ the patient for the symptoms. Many chronic pain states are post-traumatic and some may be exacerbated partly by the process of litigation that may follow an injury.

Chronic widespread pain (fibromyalgia)

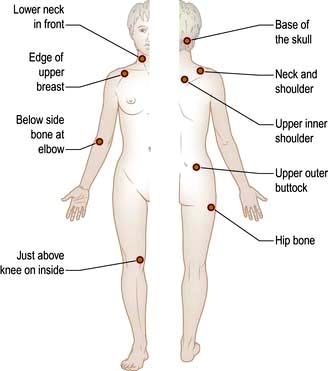

Chronic widespread pain is defined as pain for more than three months both above and below the waist (p. 1163). It is a diagnosis of exclusion although it is still not universally accepted as a diagnosis. Multiple trigger points are reported by people with fibromyalgia (see p. 1163; Fig. 11.9). The pain is widespread, with unremitting, aching discomfort. Many patients have sleep disturbances, so they awake unrefreshed and have poor concentration. Multiple other symptoms, e.g. irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), tension headaches, dysmenorrhoea, atypical facial or chest pain, often co-exist. It occurs at any age and affects women more than men (7:1).

Chronic fatigue syndrome

Diffuse muscular pain and stiffness is common in this condition, which is described on page 1162.

Hypermobility and hypermobility syndrome

Many people in the adult population have hypermobile joints (see p. 546). A small proportion are more prone to joint pains, joint instability and autonomic disturbances. This sometimes causes extreme anxiety and manifests as a chronic pain syndrome. Specific exercises to stabilize the joints, recognition of the problem and, sometimes, cognitive behavioral therapy all help. Surgery is best avoided because of problems with healing.

Analgesic and anti-inflammatory drugs for musculoskeletal problems

The key to using drugs, particularly in chronic disorders and the elderly, is to balance risk and benefit and constantly to review their appropriateness. Box 11.3 shows the main drugs available.

![]() Box 11.3

Box 11.3

Analgesics and NSAIDs

|

Analgesics (in order of potency) Advise that they be taken only if needed. Maximum doses are indicated here: |

||

|

Paracetamol |

500–1000 mg |

6-hourly |

|

Paracetamol (500 mg) and codeine (8–30 mg) |

1–2 tablets |

6-hourly |

|

Dihydrocodeine |

30–60 mg |

Every 6–8 h |

|

Paracetamol with dihydrocodeine |

1–2 tablets |

Every 6–8 h |

|

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) |

||

|

Always to be taken with food. Use slow-release preparations in inflammatory conditions or if more regular pain control is needed. Examples are: |

||

|

Ibuprofen |

200–400 mg |

Every 6–8 h |

|

Ibuprofen slow release |

600–800 mg |

12-hourly |

|

Diclofenac |

25–50 mg |

8-hourly |

|

Diclofenac slow release |

75–100 mg |

× 1–2 daily |

|

Naproxen |

250 mg |

× 3–4 daily |

|

Naproxen slow release |

550 mg |

× 2 daily |

|

Celecoxiba |

100–200 mg |

× 2 daily |

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs have anti-inflammatory and centrally acting analgesic properties. They inhibit cyclo-oxygenase (COX), a key enzyme in the formation of prostaglandins, prostacyclins and thromboxanes (see Fig. 15.30). There are two specific cyclo-oxygenase enzymes:

COX-1 is the constitutive form present in many normal tissues.

COX-1 is the constitutive form present in many normal tissues.

COX-2 is the form mainly induced in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines and not found in most normal tissues (except the kidney). It is associated with oedema and the nociceptive and pyretic effects of inflammation.

COX-2 is the form mainly induced in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines and not found in most normal tissues (except the kidney). It is associated with oedema and the nociceptive and pyretic effects of inflammation.

Coxibs and NSAIDs may reduce renal function, especially in the elderly (see Box 12.3, p. 608) and rarely cause cardiovascular events.

Short courses of NSAIDs or coxibs are used in musculoskeletal pain and in osteoarthritis and spondylosis but simple analgesia is often more appropriate.

Short courses of NSAIDs or coxibs are used in musculoskeletal pain and in osteoarthritis and spondylosis but simple analgesia is often more appropriate.

In crystal synovitis, NSAIDs and coxibs have a true anti-inflammatory effect (see p. 511).

In crystal synovitis, NSAIDs and coxibs have a true anti-inflammatory effect (see p. 511).

In chronic inflammatory synovitis, NSAIDs and coxibs do not alter the chronic inflammatory process, or decrease the risk of joint damage, but they do reduce pain and stiffness.

In chronic inflammatory synovitis, NSAIDs and coxibs do not alter the chronic inflammatory process, or decrease the risk of joint damage, but they do reduce pain and stiffness.

Slow-release preparations are useful for inflammatory arthritis and when more constant pain control is needed.

Slow-release preparations are useful for inflammatory arthritis and when more constant pain control is needed.

Be aware of the patient’s gastrointestinal and cardiac risks before prescribing NSAIDs or coxibs.

Be aware of the patient’s gastrointestinal and cardiac risks before prescribing NSAIDs or coxibs.

Osteoarthritis (OA)

Epidemiology

The prevalence of OA increases with age; it is uncommon below the age of 50 years and most people over 60 years will have some radiological evidence of it, although only a quarter of these will be symptomatic. It occurs worldwide, but with a variable distribution, e.g. in Asians, hip OA is less common and knee OA is more common than in Europeans. Women over 55 years are affected more commonly than men of a similar age. There is a familial pattern of inheritance in nodal OA and in primary generalized OA. OA has a variable distribution (Fig. 11.10). The resulting disabilities have major socioeconomic resource implications, particularly in the developed world. OA is the most common cause of disability in the Western world in older adults.

Aetiology (Box 11.4)

![]() Box 11.4

Box 11.4

Factors predisposing to osteoarthritis

Obesity: Predicts later risk of radiological and symptomatic OA of the hip and hand in population studies

Obesity: Predicts later risk of radiological and symptomatic OA of the hip and hand in population studies

Heredity: Familial tendency to develop nodal and generalized OA

Heredity: Familial tendency to develop nodal and generalized OA

Gender: Polyarticular OA is more common in women; a higher prevalence after the menopause suggests a role for sex hormones

Gender: Polyarticular OA is more common in women; a higher prevalence after the menopause suggests a role for sex hormones

Hypermobility (see p. 546): Increased range of joint motion and reduced stability lead to OA

Hypermobility (see p. 546): Increased range of joint motion and reduced stability lead to OA

Osteoporosis: There is a reduced risk of OA

Osteoporosis: There is a reduced risk of OA

Trauma: A fracture through any joint. Meniscal and cruciate ligament tears cause OA of the knee

Trauma: A fracture through any joint. Meniscal and cruciate ligament tears cause OA of the knee

Congenital joint dysplasia: Alters joint biomechanics and leads to OA. Mild acetabular dysplasia is common and leads to earlier onset of hip OA

Congenital joint dysplasia: Alters joint biomechanics and leads to OA. Mild acetabular dysplasia is common and leads to earlier onset of hip OA

Joint congruity: Congenital dislocation of the hip or a slipped femoral epiphysis or Perthes’ disease; osteonecrosis of the femoral head (see p. 556) in children and adolescents causes early-onset OA

Joint congruity: Congenital dislocation of the hip or a slipped femoral epiphysis or Perthes’ disease; osteonecrosis of the femoral head (see p. 556) in children and adolescents causes early-onset OA

Occupation: Miners develop OA of the hip, knee and shoulder, cotton workers OA of the hand, and farmers OA of the hip

Occupation: Miners develop OA of the hip, knee and shoulder, cotton workers OA of the hand, and farmers OA of the hip

Sport: Repetitive use and injury in some sports causes a high incidence of lower-limb OA.

Sport: Repetitive use and injury in some sports causes a high incidence of lower-limb OA.

Cartilage is a matrix of collagen fibres, which enclose a mixture of proteoglycans and water (see p. 494). The gene for human aggrecan has been cloned, and polymorphisms of the gene have been correlated with OA of the hand in older men.

Cartilage is smooth-surfaced and shock-absorbing. Under normal circumstances, there is a dynamic balance between cartilage degradation by wear and its production by chondrocytes. Early in the development of OA, this balance is lost and, despite increased synthesis of extracellular matrix, the cartilage becomes oedematous. Focal erosion of cartilage develops. Chondrocytes die and, although repair is attempted from adjacent cartilage, the process is disordered. Eventually the synthesis of extracellular matrix fails and the surface becomes fibrillated and fissured. Cartilage ulceration exposes underlying bone to increased stress, producing microfractures and cysts. The bone attempts repair but produces abnormal sclerotic subchondral bone and overgrowths at the joint margins, called osteophytes (Fig. 11.11). There is some secondary inflammation.

Pathogenesis

Several mechanisms have been suggested:

Abnormal stress and loading leading to mechanical cartilage damage play a role in secondary OA.

Abnormal stress and loading leading to mechanical cartilage damage play a role in secondary OA.

Obesity is a risk factor for developing OA of the hand and knee, but not the hip in later life. Increased skeletal mass increases cartilage volume.

Obesity is a risk factor for developing OA of the hand and knee, but not the hip in later life. Increased skeletal mass increases cartilage volume.

Collagenases (MMP-1 and MMP-13) cleave collagen, and other metalloproteinases such as stromelysin (MMP-3) and gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) are also present in the extracellular matrix. MMPs are secreted by chondrocytes in an inactive form. Extracellular activation then leads to the degradation of both collagen and proteoglycans around chondrocytes.

Collagenases (MMP-1 and MMP-13) cleave collagen, and other metalloproteinases such as stromelysin (MMP-3) and gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) are also present in the extracellular matrix. MMPs are secreted by chondrocytes in an inactive form. Extracellular activation then leads to the degradation of both collagen and proteoglycans around chondrocytes.

Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) regulate the MMPs. Disturbance of this regulation may lead to an increase in cartilage degradation over synthesis and contribute to the development of OA. TIMPs have not yet proven to be of therapeutic value.

Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) regulate the MMPs. Disturbance of this regulation may lead to an increase in cartilage degradation over synthesis and contribute to the development of OA. TIMPs have not yet proven to be of therapeutic value.

Osteoprotegerin (OPG), RANK and RANK ligand (RANKL) control the remodelling of subchondral bone remodelling. Their levels are significantly different in OA chondrocytes. Inhibiting RANKL may prove a new therapeutic approach in OA.

Osteoprotegerin (OPG), RANK and RANK ligand (RANKL) control the remodelling of subchondral bone remodelling. Their levels are significantly different in OA chondrocytes. Inhibiting RANKL may prove a new therapeutic approach in OA.

Aggrecanase production is stimulated by pro-inflammatory cytokines and aggrecan (the major proteoglycan) levels fall.

Aggrecanase production is stimulated by pro-inflammatory cytokines and aggrecan (the major proteoglycan) levels fall.

Synovial inflammation is present in OA, and CRP in the serum may be raised. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF-α) release stimulates metalloproteinase production and IL-1 inhibits type II collagen production. IL-6 and IL-8 may also be involved. Anticytokine therapy has not yet been tested in OA. The production of cytokines by macrophages and of MMPs by chondrocytes in OA are dependent on the transcription factor NF-κB. Inhibition of NF-κB may have a therapeutic role in OA.

Synovial inflammation is present in OA, and CRP in the serum may be raised. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF-α) release stimulates metalloproteinase production and IL-1 inhibits type II collagen production. IL-6 and IL-8 may also be involved. Anticytokine therapy has not yet been tested in OA. The production of cytokines by macrophages and of MMPs by chondrocytes in OA are dependent on the transcription factor NF-κB. Inhibition of NF-κB may have a therapeutic role in OA.

IL-1 receptor antagonist genes are associated with radiographic severity of knee OA.

IL-1 receptor antagonist genes are associated with radiographic severity of knee OA.

Growth factors, including insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) and transforming growth factor (TGF-β), are involved in collagen synthesis, and their deficiency may play a role in impairing matrix repair. However, increased TGF-β may cause increased subchondral bone density.

Growth factors, including insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) and transforming growth factor (TGF-β), are involved in collagen synthesis, and their deficiency may play a role in impairing matrix repair. However, increased TGF-β may cause increased subchondral bone density.

Cartilage breakdown products lead to macrophage infiltration and vascular hyperplasia and IL1-β and TNF-α may contribute to further cartilage degradation.

Cartilage breakdown products lead to macrophage infiltration and vascular hyperplasia and IL1-β and TNF-α may contribute to further cartilage degradation.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) from macrophages is a potent stimulator of angiogenesis and may contribute to inflammation and neovascularization in OA. Innervation can accompany vascularization of the articular cartilage.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) from macrophages is a potent stimulator of angiogenesis and may contribute to inflammation and neovascularization in OA. Innervation can accompany vascularization of the articular cartilage.

Mutations in the gene for type II collagen (COL2A1) have been associated with early polyarticular OA.

Mutations in the gene for type II collagen (COL2A1) have been associated with early polyarticular OA.

A strong hereditary element underlying OA is suggested by twin studies. Further studies may reveal genetic markers for the disease. The influence of genetic factors is estimated at 35–65%.

A strong hereditary element underlying OA is suggested by twin studies. Further studies may reveal genetic markers for the disease. The influence of genetic factors is estimated at 35–65%.

In the Caucasian population there is an inverse relationship between the risk of developing OA and osteoporosis.

In the Caucasian population there is an inverse relationship between the risk of developing OA and osteoporosis.

Gender. In women, weight-bearing sports produce a two- to three-fold increase in risk of OA of the hip and knee. In men, there is an association between hip OA and certain occupations: farming and labouring. OA may flare after the female menopause or after stopping hormone replacement therapy.

Gender. In women, weight-bearing sports produce a two- to three-fold increase in risk of OA of the hip and knee. In men, there is an association between hip OA and certain occupations: farming and labouring. OA may flare after the female menopause or after stopping hormone replacement therapy.

Periarticular enthesitis has been proposed as a factor in the pathogenesis of nodal generalized OA (NGOA; p. 515) and is the subject of investigation.

Periarticular enthesitis has been proposed as a factor in the pathogenesis of nodal generalized OA (NGOA; p. 515) and is the subject of investigation.

The term primary OA is sometimes used when there is no obvious known predisposing factor.

Box 11.4 shows some of the predisposing factors for the development of OA, and Table 11.12 shows other conditions that sometimes cause secondary arthritis.

|

Primary OA |

No known cause |

|

Secondary OA |

Pre-existing joint damage: |

|

Rheumatoid arthritis |

|

|

Gout |

|

|

Spondyloarthritis |

|

|

Septic arthritis |

|

|

Paget’s disease |

|

|

Avascular necrosis, e.g. corticosteroid therapy |

|

|

Metabolic disease: |

|

|

Chondrocalcinosis |

|

|

Hereditary haemochromatosis |

|

|

Acromegaly |

|

|

Systemic diseases: |

|

|

Haemophilia – recurrent haemarthrosis |

|

|

Haemoglobinopathies, e.g. sickle cell disease |

|

|

Neuropathies |

Clinical subsets

Localized OA

Joints of the hand are usually affected one at a time over several years, with the distal interphalangeal joints (DIPs) being more often involved than the proximal interphalangeal joints (PIPs). Nodal OA often starts around the female menopause. The onset may be painful and associated with tenderness, swelling and inflammation and impairment of hand function. At this stage, enthesitis can be seen on MRI. An intra-articular corticosteroid injection can be used at this stage, if deemed necessary. The inflammatory phase settles after some months or years, leaving painless bony swellings posterolaterally: Heberden’s nodes (DIPs) and Bouchard’s nodes (PIPs), along with stiffness and deformity (Fig. 11.12). Functional impairment is slight for most, although PIP osteoarthritis restricts gripping more than DIP involvement. On X-ray, the nodes are marginal osteophytes and there is joint space loss.

Thumb base OA co-exists with nodal OA and causes pain and disability, which decrease as the joint stiffens. The ‘squared’ hand in OA (Fig. 11.12) is caused by bony swelling of the carpometacarpal joint and fixed adduction of the thumb. Function is rarely severely compromised.

Polyarticular hand OA is associated with a slightly increased frequency of OA at other sites.

Hip OA (see p. 494) affects 7–25% of adult Caucasians but is significantly less common in black African and Asian populations. There are two major subgroups defined by the radiological appearance. The most common is superior-pole hip OA, where joint space narrowing and sclerosis predominantly affect the weight-bearing upper surface of the femoral head and adjacent acetabulum. This is most common in men and unilateral at presentation, although both hips may become involved because the disease is progressive. Early onset of hip OA is associated with acetabular dysplasia or labral tears. Less commonly, medial cartilage loss occurs. This is most common in women and associated with hand involvement (nodal generalized OA – NGOA), and is usually bilateral. It is more rapidly disabling.

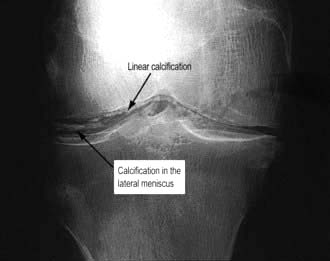

This is most commonly seen with calcium pyrophosphate deposition in the cartilage (chondrocalcinosis). Chondrocalcinosis increases in frequency with age and is seen on over 40% of knee X-rays in the over-80s, but is usually asymptomatic. The joints most commonly affected are the knees (hyaline cartilage and fibrocartilage) and wrists (triangular fibrocartilage, see Fig. 11.10). There is patchy linear calcification on X-ray (Fig. 11.13).

A chronic arthropathy (pseudo-OA) occurs, predominantly in elderly women with severe chondrocalcinosis. There is a florid inflammatory component and marked osteophyte and cyst formation visible on X-rays. The joints affected differ from NGOA, being predominantly the knees, then wrists and shoulders. Chondrocalcinosis is associated with pseudogout, an acute crystal-induced arthritis (see p. 532).

Investigations in OA

Blood tests. There is no specific test; the ESR is normal although high sensitivity CRP may be slightly raised. Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies are negative.

Blood tests. There is no specific test; the ESR is normal although high sensitivity CRP may be slightly raised. Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies are negative.

X-rays are abnormal only when the damage is advanced. They are useful in preoperative assessments. For knees, a standing X-ray (stressed) is used to assess cartilage loss and ‘skyline’ views in flexion for patello-femoral OA.

X-rays are abnormal only when the damage is advanced. They are useful in preoperative assessments. For knees, a standing X-ray (stressed) is used to assess cartilage loss and ‘skyline’ views in flexion for patello-femoral OA.

MRI demonstrates meniscal tears, early cartilage injury and subchondral bone marrow changes (osteochondral lesions).

MRI demonstrates meniscal tears, early cartilage injury and subchondral bone marrow changes (osteochondral lesions).

Arthroscopy reveals early fissuring and surface erosion of the cartilage.

Arthroscopy reveals early fissuring and surface erosion of the cartilage.

Aspiration of synovial fluid (if there is a painful effusion) shows a viscous fluid with few leucocytes (p. 498).

Aspiration of synovial fluid (if there is a painful effusion) shows a viscous fluid with few leucocytes (p. 498).

Inflammatory arthritis

Inflammatory arthritis (Table 11.14) includes a large number of arthritic conditions in which the predominant feature is synovial inflammation (Box 11.5). This disparate group includes post-viral arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, crystal arthritis, and Lyme arthritis. The diagnosis of these conditions is helped by the pattern of joint involvement (symmetrical or asymmetrical; large or small) (Table 11.14), along with any non-articular disease; a past and family history is helpful. The periodicity of the arthritis (single acute, relapsing, chronic and progressive) also helps in the diagnosis.

Table 11.14 Pattern of joint involvement in inflammatory arthritis

|

Diseases presenting as an inflammatory monoarthritis |

Diseases presenting as an inflammatory polyarthritis

There is a distinct genetic separation of rheumatoid-pattern synovitis and spondyloarthritis; RA (see below) is associated with a genetic marker in the class II major histocompatibility genes, whilst spondyloarthritis shares certain alleles in the B locus of class I MHC genes, usually B27 (see p. 526).

Early inflammatory polyarthritis

Undifferentiated polyarthritis requires urgent referral to a rheumatologist for diagnosis and treatment, including the early introduction of disease-modifying agents when indicated (see p. 523). In persistent inflammatory arthritis sustained remission depends on rapid diagnosis and intensive treatment. Poor prognostic features for undifferentiated polyarthritis are:

Rheumatoid arthritis (ra)

Aetiology and pathogenesis

The cause is multifactorial and genetic and environmental factors play a part.

Gender. Women before the menopause are affected three times more often than men. After the menopause, the frequency of onset is similar between the sexes, suggesting an aetiological role for sex hormones. A meta-analysis of the use of the oral contraceptive pill has shown no effect on RA overall, but it may delay the onset of disease.

Gender. Women before the menopause are affected three times more often than men. After the menopause, the frequency of onset is similar between the sexes, suggesting an aetiological role for sex hormones. A meta-analysis of the use of the oral contraceptive pill has shown no effect on RA overall, but it may delay the onset of disease.

Familial. The disease is familial with an increased incidence in first-degree relatives and a high concordance amongst monozygotic twins (up to 15%) and dizygotic twins (3.5%). In occasional families it affects several generations.

Familial. The disease is familial with an increased incidence in first-degree relatives and a high concordance amongst monozygotic twins (up to 15%) and dizygotic twins (3.5%). In occasional families it affects several generations.

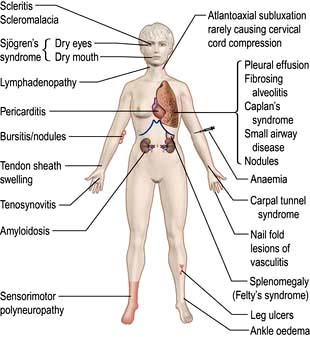

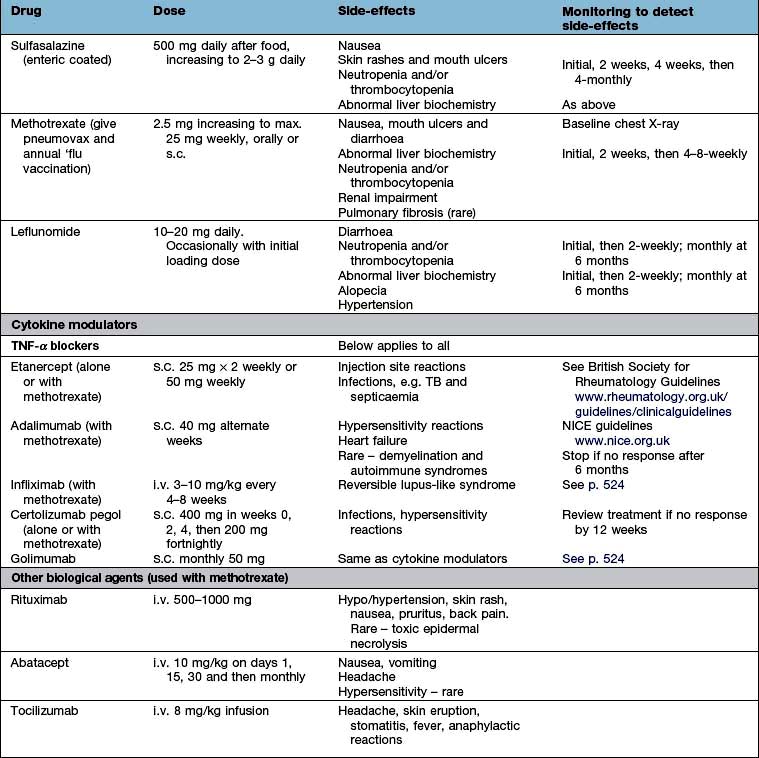

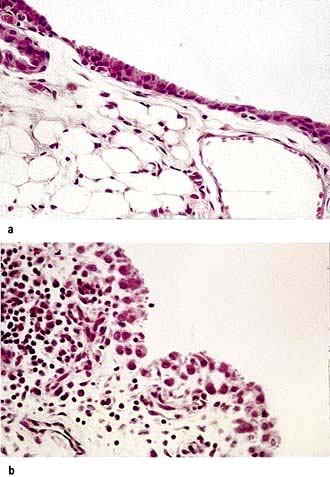

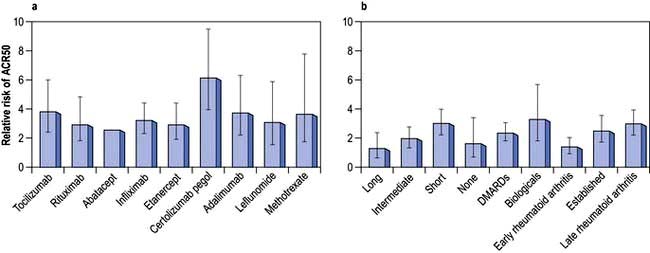

Genetic factors account for about 60% of disease susceptibility. There is a strong association between susceptibility to RA and certain HLA haplotypes: HLA-DR4, which occurs in 50–75% of patients and correlates with a poor prognosis, as does possession of certain shared alleles of HLA-DRB1*04. The possession of these shared epitope alleles in HLA-DRB1 (S2 and S3P) increases susceptibility to RA and may predispose to anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA). Citrullination is a process which modifies antigens, allowing them to fit into the shared epitope on HLA alleles. In a genome-wide association study in ACPA-positive RA, an association was found with loci near HLA-DRBI and PTPN22 in people of European descent. These genes affect the presentation of autoantigens (HLA-DRBI), T cell receptor signal transduction (PTPN22) and targets of ACPA (PAD14).