Chapter 17. Rheumatoid arthritis and other arthropathies

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease that causes chronic inflammation and destruction of synovial joints. It is the commonest chronic inflammatory disease of joints, and affects 3% of women and 1% of men. The inflammation is a result of an abnormality of both cellular and humoral immunity but the cause of the disease itself is still unknown.

Because it is a systemic disease, many different structures all over the body are affected, in contrast to osteoarthritis, which is due to localized mechanical wear. Although rheumatoid arthritis is primarily treated by rheumatologists and described more fully in medical texts, it frequently involves orthopaedic surgeons and the orthopaedic aspects are described here.

Pathology

Rheumatoid arthritis is primarily a disease of the synovium. Affected synovium contains plasma cells and lymphocytes, a reflection of the autoimmune nature of the disease. The aetiology has been thought to be associated with an infectious origin, or possibly genetic (an abnormal HLA-Dw4 focus). Regardless of the exact trigger mechanism, lymphocytes are activated and chemical messengers initiate destructive cascades that may ultimately lead to joint destruction. These chemicals include phospholipase A2, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), plasminogen activators and interleukin-1 (IL1).

Untreated, the synovium swelling and inflammatory reaction gradually affect neighbouring structures. Articular cartilage is damaged and the surrounding ligaments may become lax, and bone destruction makes these even looser.

Ultimately, there is destruction of joint cartilage, capsule and ligaments, which causes instability, mechanical disarray, subluxation and deformity (Fig. 17.1 and Fig. 17.2).

|

| Fig. 17.1

Rheumatoid arthritis of the foot with destruction of the small joints.

|

|

| Fig. 17.2

Late rheumatoid arthritis of the hands with destruction of the small joints.

|

Clinical features

This is often of insidious onset with morning stiffness and polyarthritis. It most commonly affects the small joints of young adults between the ages of 15 and 35. Women are more commonly affected than men.

The disease begins with swelling of the small joints of the hands and feet, and the pannus ingrowth gradually denudes articular cartilage and leads to chondrocyte death. The synovial swelling is best seen in the fingers and the valleys between the metacarpal heads (Fig. 17.3).

|

| Fig. 17.3

Rheumatoid of the hand and wrist with characteristic deviation and swelling.

|

Because rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic disease, it also involves extra-articular structures. Rheumatoid nodules form in the subcutaneous tissues and may need to be excised if they rupture or lie on the subcutaneous border of the forearm, where they interfere with the use of crutches (Fig. 17.4). They are, however, prone to recurrence. The skin becomes thin and fragile and this makes wound healing difficult and unpredictable. The sclera of the eye and cardiac muscle can also be affected.

|

| Fig. 17.4

Rheumatoid nodules at the elbow.

|

The progress of the disease is variable. Patients experience occasional ‘flare-ups’ relieved by drugs and rest. A small minority develop the crippling deformities that make rheumatoid arthritis such a disabling disease.

Investigations

The diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis is essentially clinical. A useful screening tool is the inclusion of one or more of the following:

1. Morning stiffness > 1 h.

2. Swelling (synovitis).

3. Characteristic distribution of joints.

4. ESR 20 mm/h.

5. Nodules.

7. Radiographic findings – erosions of hands and feet.

8. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are beneficial.

9. First degree relative with inflammatory joint disease.

The earliest radiographic changes are seen around the small joints of the hands and feet, where erosions occur at the carpometacarpal and interphalangeal joints (Fig. 17.5). Periarticular erosions and osteopenia are probably the first signs.

|

| Fig. 17.5

Rheumatoid arthritis with involvement of the small joints.

|

Because rheumatoid arthritis is due to an abnormality of the autoimmune system, the ESR and CRP are raised, along with various agglutination tests, such as sheep cell agglutination test (SCAT) and latex tests. Thirty percent of patients test negative despite having the typical clinical appearance of rheumatoid arthritis. Such patients are said to have ‘seronegative’ rheumatoid arthritis. The rheumatoid factor (antibody test) is positive in 80%.

Recently, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibody elevation has been shown to be more sensitive and specific than the rheumatoid factor. These antibodies may be present in 50–60% of patients with early signs of the disease (before rheumatoid factor becomes positive). Their use may help stage the disease and give an accurate prognosis with treatment.

Systemic manifestations include pericarditis and pulmonary disease (pleurisy, nodules and fibrosis). Popliteal cysts in rheumatoids can mimic thrombophlebitis or, when ruptured, a deep vein thrombosis. Felty’s syndrome includes an enlargement of the spleen and leucopenia. Still’s disease is a rapid onset of rheumatoid arthritis associated with a fever, rash and splenomegaly. When associated with inflammation of the glands of the eye and mouth giving dryness in these areas it is called Sjögren’s syndrome.

Treatment

The aim of treatment is to control synovitis and pain as well as maintaining joint function and the prevention of long-term deformities. A multidisciplinary approach between rheumatologists, orthopaedic surgeons and physical therapists is often necessary.

Conservative treatment

Conservative treatment of rheumatoid arthritis involves the use of the following:

Conservative measures in rheumatoid arthritis

1. Drugs.

2. Rest during an attack and mobilization during remission.

3. Aids and appliances.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. These are the first line of treatment and include aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, etc. Patients may require steroids taken orally, or injected into affected joints in severe cases. These drugs help modify joint pain and inflammation.

Second line drugs or disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDS) may help prevent joint destruction and subsequent deformity. These slow-acting drugs may take months to become effective and are often used for long periods of time, sometimes years. If effective, these DMARDS may promote remission, and they are often used in combination and together with first line drugs. Second-line drugs include quinine, sulfasalazine, gold, penicillamine or immunosuppressive therapies such as methotrexate, azathioprine and cyclophosphamide. Newer drugs aim to block the production of the inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor (antiTNF) and interleukin-1.

Rest and immobilization. Splintage and rest will also reduce the swelling of joints and it can induce remission of the disease in an acute attack. Rest may require admission to hospital. Restoration of joint movement by physiotherapy when the attack has passed is essential.

Aids and appliances. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis need a host of appliances. Sticks, frames and crutches take the weight of lower limbs; splints and braces protect painful joints from unnecessary movement; and soft protective footwear relieves the pressure on vulnerable skin (Fig. 17.6).

|

| Fig. 17.6

Surgical shoes to accommodate a foot deformity.

|

Operative treatment

Operative treatment may be required for three reasons, but only if medical treatment has failed.

Indications for operations in rheumatoid arthritis

1. To remove inflamed synovium by synovectomy.

2. To repair damaged soft tissue.

3. To salvage destroyed joints.

Synovectomy. If conservative measures do not reduce the synovial swelling, a surgical synovectomy may be required. Unless done arthroscopically this is an extensive operation and requires considerable rehabilitation. Once done, the joint is less liable to flare-ups of the disease in the future and progression of the disease may slow. Synovium can also be removed from around the tendon sheaths, and at the wrist this may reduce the risk of future tendon rupture.

Repair. Ruptured extensor tendons at the wrist need to be repaired and unstable metacarpophalangeal joints stabilized by soft tissue procedures. Rheumatoid nodules and cysts around the joints, such as popliteal cysts at the knee, may need excision.

Salvage. In late rheumatoid arthritis with destroyed joints, salvage operations are necessary. Joint replacement is effective in the weight-bearing joints of the lower limb. Arthrodesis may be the treatment of choice at the wrist and in other joints of the upper limb, although more recently replacement procedures have proved to be effective, in the shoulder and elbow in particular. Spinal fusion is sometimes needed for instability of the cervical spine or segments.

Operating on a patient with widespread joint destruction has far-reaching effects on other joints as well, and the impact of the operation on the patient as a whole must be carefully considered. Surgery should never be undertaken for patients with rheumatoid arthritis without careful assessment. This may not be possible in a single outpatient consultation. Assessment requires many visits to the physiotherapist or occupational therapy department to determine the operation most likely to bring long-standing relief.

Undiagnosed joint pain

Many patients in the second and third decades of life develop symmetrical pains in the small joints of the hands and feet or, less often, the large joints and are referred to a rheumatologist. The majority of these patients, perhaps as many as 80%, yield no abnormality on thorough investigation. Most patients make a complete recovery over a period of months or years and do not have rheumatoid arthritis.

Other arthropathies

Crystal arthropathies

Crystals can be deposited in joints or soft tissue because of a metabolic abnormality. The accumulation of crystals probably begins in infancy but is not usually apparent until the third or fourth decade. Deposits of crystals in and around joints often remain asymptomatic but they can also cause two types of arthritis:

1. Acute self-limiting attacks of inflammation.

2. Chronic destructive joint disease.

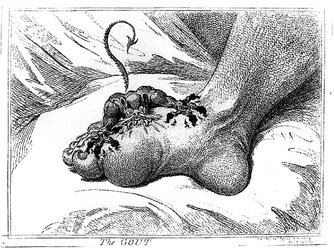

Gout

The commonest and best known crystal arthropathy is gout, in which urate crystals are deposited (Fig. 17.7). Traditionally, the condition affects the first metatarsophalangeal joint and is precipitated by an excess of red meat or port wine. This bucolic image is incorrect; the condition can occur at any age and diet is only rarely involved. Dehydration following major trauma or operation, soft tissue destruction caused by chemotherapy or radiotherapy for malignant disease, and the use of diuretics in the elderly are more frequent precipitating factors. Alcohol abuse is but one cause of dehydration.

|

| Fig. 17.7

The gout.

James Gillray, 1799. By kind permission of the Wellcome Institute Library, London.

|

These conditions are most often seen and treated by the rheumatologists but it is important for orthopaedic surgeons to be aware of them because the painful swollen joints can present to an orthopaedic clinic and be mistaken for septic arthritis or an internal mechanical derangement.

Treatment of the acute attack is by anti-inflammatory drugs. Indometacin 50 mg three times daily usually produces dramatic relief but systemic steroids are sometimes required. Aspiration of the knee and irrigation is helpful and allows the joint fluid to be centrifuged and examined for cells and crystals. Polymorphs are usually seen, and birefringent crystals are sometimes identified under polarized light.

If the attacks recur, long-term treatment with allopurinol may be helpful and this is best conducted by a rheumatologist.

Pyrophosphate and hydroxyapatite deposition (pseudogout)

Atypical gout (pseudogout) produces a similar clinical picture to gout but the crystals involved are calcium pyrophosphate. Both pyrophosphate and hydroxyapatite deposition may follow either local or systemic disorders and be associated with acute inflammatory synovitis or chronic joint destruction (Fig. 17.8).

|

| Fig. 17.8

Calcification of the menisci.

|

Treatment is similar to that for gout but long-term treatment with allopurinol is not effective.

Psoriatic arthropathy

Psoriatic arthropathy can involve the small joints of the hands and feet but can also cause a large effusion in a single joint. Beware of the patient with psoriasis who has a swollen joint without obvious explanation: operation is unlikely to be helpful.

Treatment is similar to rheumatoid arthritis, but the condition is seldom as severe.

Haemophiliac arthropathy

Bleeding disorders of any type can cause recurrent intra-articular haemorrhage into any joint but the knee is most often affected (Fig. 17.9). The blood causes a synovitis and leads to pigmentation of the synovium. The articular cartilage is also involved and develops craters and pot-holes filled with dark brown synovial fronds. In time the subsynovial layers become fibrotic, the capsule loses its flexibility and the articular surfaces undergo degenerative change.

|

| Fig. 17.9

The effects of haemophiliac synovitis.

|

Diagnosis is usually simple because most haemophiliacs know they have the condition and carry a card with details of the exact diagnosis and the treatment they have received.

Treatment. Most patients nowadays have a supply of cryoprecipitate which they administer themselves at the first sign of bleeding into a joint.

If this is not the case, the first step is to rest the limb and contact the haematologist in charge of treatment. The appropriate clotting factors are then administered and the joint aspirated when it is safe to do so.

If the joint develops a proliferative synovitis that never really settles, recurrent bleeding is likely. In some circumstances it is possible to remove the affected synovium but this is a hazardous undertaking in a haemophiliac unless the synovectomy is done arthroscopically. At the knee, arthroscopic synovectomy yields good results in selected patients.

Remember that many unfortunate haemophiliacs have become infected with the HIV or hepatitis virus through blood products such as cryoprecipitate. Special care must be taken to avoid accidental infection of those caring for these patients.

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS)

Any chronic synovitis accompanied by recurrent small bleeds stains the synovium dark and causes thickening of the deep layers with patches of proliferative synovial villi. The synovium becomes pigmented, nodular and villous. PVNS is essentially a macroscopic description of the end result of chronic synovitis and recurrent bleeding rather than a separate disease entity.

Treatment. The condition usually settles slowly with time, but recovery can be hastened by excising inflamed areas, if possible by arthroscopy. If the inflammation cannot be controlled, a persistent synovitis a little like haemophilic synovitis will follow.

Synovial chondromatosis

Any joint may be affected by synovial chondromatosis, in which masses of articular cartilage develop either in the synovium or within the synovial cavity. These cartilage masses may become ossified, and appear as multiple loose bodies (Fig. 17.10). If the symptoms are severe, the abnormal tissue must be removed, but recurrence is common.

|

| Fig. 17.10

Multiple loose bodies in synovial chondromatosis.

|

Bone necrosis

Bone necrosis can occur from the following causes:

1. Corticosteroid administration.

2. Blood dyscrasias (such as sickle cell disease and thalassaemia).

3. Gaucher’s disease.

4. Alcoholism.

5. Caisson disease.

6. Spontaneous osteonecrosis.

Steroid necrosis. High doses of corticosteroids are sometimes necessary after transplant surgery or to suppress the immune response for other reasons, and may be accompanied by separation of large fragments of bone (Fig. 17.11). The separated fragments are avascular but the exact pathogenesis is unclear.

|

| Fig. 17.11

Steroid osteonecrosis. A fragment of the lateral femoral condyle has separated and is lying with the convex femoral surface facing upwards.

|

Blood dyscrasias. Patients with homozygous sickle cell disease, or occasionally patients with thalassaemia, are susceptible to episodes of spontaneous bone necrosis. This can follow periods of anoxia but can also occur without obvious cause.

Gaucher’s disease. This is a rare cause of bone necrosis but should be remembered, if only for examination purposes.

Alcoholism. Alcohol abuse can lead to necrosis of the femoral heads and occasionally the weight-bearing parts of other joints. The diagnosis is often difficult because of the patient’s denial of the problem.

Caisson disease. ‘Caisson’ does not refer to a person and to talk of ‘Caisson’s’ disease is incorrect. A caisson is a large metal vessel placed under water and filled with compressed air so that labourers can work within it for tunnelling and bridge-building projects. The workers may develop decompression sickness when they come to the surface, gas bubbles form within the bones and bone necrosis follows. The condition is now more commonly seen in deep-sea divers and may occur even in the presence of strict decompression procedures.

Spontaneous osteonecrosis can occur for no obvious reason, particularly at the knee. The condition is described on page 419.

Neuropathic arthropathy

Joints with deficient sensory innervation develop a rapidly progressive destructive arthropathy. It is suggested that the denervation allows the patient to apply enormous loads to the joint without the protection of normal reflexes, but other factors may be involved.

The condition was described by Charcot in patients with tabes dorsalis, in whom the condition can correctly be called a ‘Charcot joint’.

Neuropathic joints can be seen whenever a joint is denervated, but the following are the commonest causes:

1. Diabetes mellitus.

2. Syringomyelia.

3. Late syphilis.

4. Denervated limbs.

A similar appearance is seen in patients taking large doses of analgesic and anti-inflammatory drugs, perhaps because they also lack the sensory arm of their protective reflexes.

Clinically, the joints are swollen, grossly unstable, inflamed and painless. Radiological examination shows widespread bone destruction and loss of bone architecture.

Treatment. There is no treatment for a neuropathic joint except stabilization in a caliper or orthosis. Operation should not be attempted on a neuropathic joint because arthrodeses do not join and prostheses tear out of the bone.

Reiter’s disease

Reiter’s disease is acquired through sexual contact or as a sequel to dysentery and includes the following features:

1. Conjunctivitis.

2. Urethritis.

3. Synovitis.

The condition can affect any joint but the small joints of the hands and feet are most often involved. Large joints such as the knee are affected less often. The diagnosis should be considered in any patient, especially men, with these symptoms.

Treatment. The condition usually resolves spontaneously but anti-inflammatory drugs are helpful.

Arthropathies following infection

Brucellosis, typhoid and viral illnesses can all be followed by generalized joint disease resembling rheumatoid arthritis. The orthopaedic surgeon need not become involved in the management of these difficult problems but must always be aware that a single painful joint can be the first manifestation of a generalized joint disorder and should avoid operating without good reason.

Ankylosing spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis is essentially a disease of the spine (p. 455) but it also involves the large joints, such as hip, knee and shoulder. The disease is commoner in men than women by 6 : 1 and usually presents between the ages of 15 and 30 years.

Treatment consists of anti-inflammatory drugs and physiotherapy. Cervical and lumbar osteotomy may be needed for late deformities. Joint replacement is often unsuccessful because the new joints also become ankylosed.

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy

This should be called a complex regional pain syndrome as there were previously a number of terms describing the same process. They included causalgia, Sudek’s atrophy (e.g. following a Colles fracture, p. 215), post-traumatic dystrophy, shoulder–hand syndrome, algodystrophy, algoneurodystrophy and reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Regional pain syndrome can be further divided into two types: type 1 with features not associated with a specific nerve injury and type 2 with a specific nerve (more akin to the condition previously described as causalgia). Both types present with an exaggerated pain response, intolerance of temperature and often a blotchy discoloration of the skin. There may also be colour changes on the limb, usually blue or purple patches. The condition can be precipitated by trauma of any kind, including operation.

The syndrome can be made worse by trauma, even by a trivial procedure such as arthroscopy. For this reason, operations should not be undertaken on painful joints that go cold or blue and have no mechanical symptoms.

Investigations are usually unhelpful. A thermogram may show an altered pattern but radiographs are normal except in very late cases when there is osteoporosis.

Treatment

Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulators, beta blockers and guanethidine injections to the affected limb are often helpful and chemical sympathectomy is sometimes required. Calcitonin has been shown to be of value. Physiotherapy and joint mobilization are vital. Prolonged bracing will only lead to stiffness and muscle wasting.

Monarticular synovitis in a large joint

Many patients present with pain and swelling confined to one joint without any history of injury or mechanical symptoms. The common causes are as follows:

1. A mechanical derangement. In the knee, a torn meniscus or defect in the articular cartilage is often responsible.

2. Gout or pseudogout.

3. A disorder of synovium, such as ankylosing spondylitis or rheumatoid arthritis.

4. Psoriatic arthropathy. Always ask a patient with acute monarticular synovitis if they have psoriasis or any other rash.

5. Reiter’s disease.

6. Septic arthritis, including gonococcal arthritis.

7. Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis is perhaps the commonest cause of pain and swelling in a large joint. Quite severe degenerative changes can be present before any abnormality can be seen on the radiograph.

8. Synovial chondromatosis (p. 307).

9. Spontaneous osteonecrosis (p. 307).