Chapter 36 Rheumatoid arthritis

With contribution from Greg de Jong

Introduction

Affecting between 0.5–1.% of the population, rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disorder that progressively destroys articular joint function through excessive inflammation of synovial tissue and other local structures.1 This process can be rapid enough that when left untreated 20–30% of people can be seriously afflicted such that they become permanently work disabled as a result of the disease process within 2 years.2 However widespread systemic influences are also prevalent, so much so that mortality amongst rheumatoid arthritis sufferers is 1.5–1.6 times greater than the general population.3

Early identification of rheumatoid arthritis is considered critical as prompt intervention provides a window of opportunity to limit progressive damage from the disease process.5 Significantly one-third of patients with rheumatoid arthritis already have bone and joint damage prior to diagnosis and it has been identified that a delay in initiating treatment, (with Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs DMAR), of as little as 3 months can have significant impact on the amount of observable X-ray damage identified 5 years later.6 (Examples of DMAR: Methotrexate, leflunomide, sulfasalazin, gold, hydroxychloroquinine, etanercept, inflixima, adalimumab.) This has led to growing interest in the use of anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibody markers as an indication of the early presence and, potentially, a prediction of the development of rheumatoid arthritis amongst both healthy people and those with undifferentiated arthritis.7, 8 Disease progression indicators include early low functional scores, low economic status, early multiple joint involvement, high erythrocyte sedimentation rates, high C-reactive protein measures, early X-ray changes and/or a positive rheumatoid factor.2

Individuals with rheumatoid arthritis commonly use complementary and alternative medicines (CAM). Reasons given include: the inadequacy of conventional treatment to meet the needs of the patient (disease remission, decrease pain, return of function and so on); concern regarding side-effects; a desire to reduce the stress of a disease; patients consider CAM as safer and ‘natural’; and/or that they have been influenced by advertising claims.9 Interestingly, a US study identified that the likelihood of using CAM therapies for a number of musculoskeletal conditions including rheumatoid arthritis increased with the degree of scepticism of the user of mainstream medical approaches.10

Lifestyle factors

Genes

Genetic factors are estimated to comprise 50–60% of the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis.1 Growing evidence suggests an interactive link between genetic susceptibility (e.g. HLA-DR genetic profile) and environmental triggers (e.g. smoking) that lead to the eventual immunological assault of the disease.11, 12

Smoking

The immune system is influenced by smoking on many levels — the induction of an inflammatory response, suppression of immune responses, cytokine imbalance, induction of apoptosis and the formation of anti-DNA antibodies as a result of DNA damage.13 Unsurprisingly therefore, a strong association is present between tobacco use and extra-articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis, including cardiovascular events, although not to the extent of radiographic changes.14

In a subset of rheumatoid arthritis patients the presence of an HLA-DR shared epitone gene also interacts with smoking leading to immune system dysregulation and the formation of autoantibodies to citrullinated peptides significant to the disease process.11, 12 Significantly this immune system response as a result of gene-smoking interaction may be initiated years before symptomatic presentation of rheumatoid arthritis.11 Smokers who have the HLA-DR gene are also at higher risk (7.5) of rheumatoid factor seropositive rheumatoid arthritis than non–smokers with the gene (2.8), or smokers without the gene (2.4) as compared with non-smokers/no gene (1.0).15

It has therefore been suggested that smoking cessation counselling should be mandatory for all rheumatoid arthritis patients and their relatives.16

Nutritional influences

Diets

A review of dietary factors considered to diminish the risks of rheumatoid arthritis indicate that foods high in olive oil, oil-rich fish, fruit, vegetables and betacryptoxanthins (found in red fruit and vegetables) were protective for rheumatoid arthritis.17, 18 A review of trials on red meat, coffee and alcohol demonstrated mixed results and no firm conclusions could be made as to their influence on rheumatoid arthritis.17 However, these conclusions differ to a further study of diet and risk which indicated that although consumption of high-fat fish (> or = 8g of fat/100g fish) appear to provide a risk reduction, medium-fat fish (3–7g/100g fish) was actually associated with increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis. A prospective study by the Mayo Clinic suggested that cauliflower, broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables and fruit were protective of rheumatoid arthritis.19 However, a further study indicated that fruit, coffee, olive oil and meat intake showed no association with rheumatoid arthritis risk reduction, nor did intake of vitamins A, E, C, D, zinc, selenium or iron.20 A review of studies into the relationship between obesity and rheumatoid arthritis presently suggests obesity may lead to less changes on radiography and better survival rates, although this needs to be confirmed.21 Hence, the implications of diet on the risk of rheumatoid arthritis is, presently, contradictory.

Vegetarian and vegan diets have been advocated for rheumatoid arthritis patients. A 13-month trial in which a period of fasting was followed by a vegetarian diet indicated that pain diminished but physical function and morning stiffness did not change in the active group.22 A vegan diet free of gluten provided benefit for 40.5% of the active group who completed 1 year of the diet plan. Notably, however, only 25 of 38 patients in the active vegan group were able to comply with 9 months or more of the program, suggesting compliance is a problem.23

Studies of Mediterranean (Cretan) diets, suggests they may be of benefit in reducing the pain of rheumatoid arthritis when committed to over a 12-week period.24, 25 A UK pilot study trialled a pragmatic approach to the Mediterranean diet by providing community-based intervention that included hands-on cooking classes. As a result a change in dietary patterns was noticed with an increase in fruit, vegetable and legume consumption and improvements in monounsaturated: polyunsaturated fats ratios. Significant improvements were observed for pain and morning stiffness scores at 6 months.25

Studies of food allergies and/or intolerances suggest the possibility of an involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid arthritis patients have been found to have increased immunoglobulin M (IgM) activity to cow’s milk (alpha-lactalbumin, casein), cereals, hen’s eggs (ovalbumin), cod fish and pork meat within their intestinal fluid.26 It was postulated that such activity amongst other examples of cross-reactive food antibodies may ultimately lead to autoimmune responses in the joint via hypersensitivity reactions to circulating immune complexes.26 Consistent with this, small trials of an elemental diet indicate the potential for improvement in rheumatoid arthritis patients.27–29. A review of allergens in 1 trial indicated that grains, milk, beef and eggs were common culprits.27

It must be highlighted that a Cochrane review (2009) concluded that the effects of diet remain uncertain due to the nature of the identified trials and the risk of bias. The review raised further concerns that all of the above diets (Mediterranean, fasting, vegan, vegetarian, elemental) risked both non-compliance and weight loss within patient groups and there was the potential for adverse effects as a result.30

Sleep

Sleep disturbances appear to be common amongst patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Amongst arthritis sufferers in general 60% of patients experience problems with sleep,31 including 72% of patients above 55 years of age.32 The problem also exists amongst children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.33 Despite this sleep difficulties are seldom addressed with rheumatoid arthritis sufferers.31 Sleep disturbances include longer times to fall asleep, repetitive night waking and early morning waking with subsequent day tiredness and fatigue.34

Mind–body medicine

Adjustment to the pain and disability that result from rheumatoid arthritis require psychological and emotional resilience. Capacity to initiate active coping strategies has been identified as critical in maintaining psychological wellbeing.35, 36 As a result various mind–body medicine approaches have been advocated to aid coping with rheumatoid arthritis.

Cognitive behavioural therapies (CBTs) and education

CBT approaches may provide additional benefit to depressive symptoms in rheumatoid arthritis receiving routine medical management up to 18 months after an 8-week program.37 However, a study of CBT comparing CBT to a standard education program for newly diagnosed arthritis patients found there was no difference on health status between the 2 approaches over 6 months.38

A Cochrane review (2003) indicated that patient education was of small benefit to rheumatoid arthritis in the short term, improving disability, joint count, depression and psychological status, yet there was little evidence that gains were maintained over the long term.39 However studies continue to mount suggestive of benefits from arthritis education programmes subsequent to this review. Disease specific programs appear to be more valuable than generalised chronic self help programs.40 Internet41 and modular delivered behavioural arthritis programs42 may be viable means of delivering information compared to standardised approaches.

Small studies indicate several mind-body medicines have the potential of influencing aspects of rheumatoid arthritis. Stress management programs decrease pain and psychological functioning by improving self-efficacy, coping strategies and overcoming feelings of helplessness.43 Brief motivational training by telephone has also been demonstrated to assist in cognitive and emotional coping.44 Tentative evidence suggests that private verbal or written emotional disclosure may be effective in the intermediate term to maintain psychological functioning, noting in the short term they may cause an increase in emotionality.45–47. However, results are mixed, and a further study of private emotional disclosure and, in particular, emotional disclosure in the presence of a clinician, was of no significant benefit.48

Meditation and/or relaxation

A study comparing cognitive behavioural therapies, emotional regulation and mindfulness meditation delivered in small group environments identified that rheumatoid arthritis patients who suffered with recurrent depression had greater benefit from meditation in terms of positive and negative effect and physician ratings of joint pain, whereas CBTs provided greater gains in pain control.49 Positive effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction may be beneficial in aiding psychological distress and wellbeing as compared to controls, however, gains may take up to 6 months to be achieved.50 The use of Benson’s Relaxation Technique has shown benefit in a small study of 8 weeks as compared to controls in reducing anxiety, depression and feelings of wellbeing.51 These early studies suggest that meditation and/or relaxation may have potential in improving the wellbeing of rheumatoid arthritis patients.

Physical activity/exercise

Comprehensive multidisciplinary approaches to rehabilitation often involve a combination of therapeutic and general exercise, occupational therapy and the use of orthotic splints. Such programs should be introduced as early as possible and concurrent with pharmacological intervention.52 However, due to a paucity of trials in this area little is known as to the extent of effectiveness other than by inference from evidence for the individual therapies themselves within a program.53

Aerobic exercise

A review of reconditioning programs has established that dynamic and aerobic activity individualised to the patient’s level of disability is more beneficial than rest in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and the activities do not aggravate inflammation nor cause joint damage. The goal of such programs should be to avoid functional decline.54 There is strong evidence from a systematic review suggesting that exercise, whether of low or high intensity, is effective in improving disease and functional Balneotherapy (hydrotherapy and spatherapy) measures in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.55

Balneotherapy (hydrotherapy and spatherapy)

Noting that methodological flaws and poor study structure in trials of balneotherapy are prevalent (spa therapy, hydrotherapy), present evidence is suggestive that it is of benefit for the patient with rheumatoid arthritis.56

Tai chi

A Cochrane review (2004) of tai chi for rheumatoid arthritis indicated statistically significant benefits were obtained with measures of lower extremity range of motion improving. This form of exercise does not appear to exacerbate symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis, however the review did not identify improvements in most other outcomes of disease activity.57 While subsequent small trials continue to be suggestive of benefits to pain, fatigue and function scores as compared to no intervention,58, 59 tai chi does not appear to provide additional benefit when compared to physically active controls or stretching and an exercise program.60

Nutritional supplements

A New Zealand review of micronutrient adequacy of the diets of patients with rheumatoid arthritis demonstrated that only 23% achieved adequate calcium intake (as compared to recommended dietary intake [RDI]), 29% adequate vitamin E, 10% adequate zinc and only 6% adequate selenium.63 Only 46% reached adequate RDI for folic acid, with a significant reduction noted in the subgroup of patients taking methotrexate. Protein intake and iron were adequate, and unrelated to the presence or absence of anemia.63 A US dietary review suggested that rheumatoid arthritis patients consumed excess total fat but insufficient polyunsaturated fat and fibre, with inadequacies in pyridoxine, zinc and magnesium compared to the RDI, and copper and folate when compared to the typical American diet.64

Omega-3 (fish oils)

High-level evidence now exists for the symptomatic benefit achieved from fish oils and, given the increased risk of cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis patients, they should be recommended to all patients.65 The anti-inflammatory effects of fish oils result from their influence on eicosanoid pathways leading to less pro-inflammatory cytokines, as well as an inhibition of T-lymphocytes and catabolic enzymes.66 A meta-analysis of 3–4 months use of fish oils amongst rheumatoid arthritis patients demonstrated reductions in joint pain intensity, morning stiffness, number of painful/tender joints and a reduction in the consumption of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).67 Animal models are also suggestive of the potential for omega-3 oils to slow the disease process and reduce disease severity.68

Gamma linoleic acid (omega-6, evening primrose oil, borage)

A Cochrane review (2000) indicated that evidence existed for the potential benefit of gamma linoleic acid (GLA) in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with improvements in pain, morning stiffness and joint tenderness noted.69 Like fish oils, GLA down regulates the pro-inflammatory pathways active in rheumatoid arthritis,70 however, it is not thought to alter the disease process.71 Indeed, although patients are often able to reduce or even stop their NSAID with GLA usage,70 symptoms often return within 3 months once supplementation is ceased.71 Dosages of up to 2.8g/day have been trialled with success.71

Antioxidants

A cohort study of older women examining the relationship between antioxidant and micronutrient intake and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis noted an inverse relationship between intake of vitamin C, vitamin E and betacryptoxanthin (found in red fruit and vegetables) and the presence of rheumatoid arthritis.72 However, a systematic review of randomised clinical trials (RCTs) relating to the use of antioxidant vitamins (2007) indicated that evidence was lacking as to the benefits of supplementation.73

In the abovementioned review, 4 trials of vitamin E suggested that vitamin E was superior to placebo but equivalent to diclofenac in treating rheumatoid arthritis, however, methodology of the trials was weak.73 However, a large trial of near to 40 000 healthy female patients concluded that there was no evidence that the use of 600IU vitamin E supplementation prevented the development of rheumatoid arthritis during a 10-year follow up as compared to a no supplement control group.74

A subsequent trial in 2008 in which a pilot group of rheumatoid patients consumed 20g of an antioxidant rich spread per day (10 weeks) suggested improvements in the number of swollen joints and general health, although no change in laboratory markers was noted.75

Vitamin D

It has been established that vitamin D3 has a significant role in the maintenance of immune homeostasis including the regulation of normal immune tolerance to self.76 This is relevant to rheumatoid arthritis and may explain both latitude and seasonal variations in rheumatoid arthritis activity as a consequence of the essential sunlight–vitamin D interaction.77 Furthermore, preliminary evidence suggests the potential that a subgroup of rheumatoid arthritis patients may be influenced by the presence of a vitamin D gene polymorphism that contributes to their illness.78 Vitamin D intake also appears to be inversely proportional to the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis as established by a Women’s Health Study of 29 368 women aged between 55–69 years. In this study the results were significant in regard to total dietary and supplementary intake of vitamin D with both reducing the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis.79

It has therefore been argued that a careful balance must be achieved between the risk of sun exposure and sun neglect in patients as vitamin D deficiency is an important risk factor (e.g. for autoimmune diseases and rheumatoid arthritis) and that vitamin D supplementation should be considered.80

Zinc

A review of the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis established that the use of supplemental zinc has a protective effect.72 Plasma zinc levels have been found to be low in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and correlate with bio-humoral and clinical markers of the disease.81 However, there appears to be little present evidence to suggest whether zinc supplementation is of benefit in rheumatoid arthritis or not.

Iron

Iron deficiency appears common amongst patients with rheumatoid arthritis, estimated at 33–60%. A systemic review of anaemia in rheumatoid arthritis suggested patients with anaemia usually had more severe disease and that the treatment of the anaemia assisted in the successful treatment of the overall disease process.82 It should, however, be noted, that iron is linked to acceleration of reactive oxygen species in the inflammatory process83 and that a haemochromatosis-linked arthritis exists,84 such that definitive clinical measures and care need be taken in the use of iron supplements in the patient with rheumatoid arthritis.

Glucosamine

Despite widespread research and usage in osteoarthritis, there are few studies that evaluate the effectiveness of glucosamine specifically upon rheumatoid arthritis. Two small Japanese studies provided conflicting evidence; glucosamine is either effective in providing symptomatic but not anti-rheumatic effects,85 or it is ineffective (along with chondroitin and quercetin) on all disease parameters of rheumatoid arthritis.86

Herbal medicines

An evaluation of the benefits of herbal medicine on rheumatoid arthritis is made difficult by the recommendation of numerous herbs, most with low levels of supportive evidence based on single, often methodologically flawed, trials.87

Two trials using 1200mg/day of curcumin both demonstrated improvements in pain, morning stiffness and swelling.88, 89 Single trials have also suggested that pomegranate extract,90 garlic,91 ginger,92 bromelain,93 cat’s claw,94 and boswellia95 may be effective, although confident recommendation requires to be justified by further trials.

A systematic review of Ayurvedic medicinal approaches to rheumatoid arthritis found a paucity of evidence and that existing trials failed to demonstrate any effect.96

Several Chinese herbal medicines have been studied for their potential benefit for rheumatoid arthritis patients, however, evidence is generally lacking. The most commonly studied TCM herb, Tripterygium wilfordli (thundergod vine), has been demonstrated to have beneficial effects according to a systematic review of randomised trials, however, the authors noted that a risk–benefit analysis suggested that due to concern for serious side-effects (renal, cardiac, haematopoietic and reproductive complications) the herb could not be recommended for use.97

Physical therapies

Little evidence exists as to the efficacy of massage and manipulation in rheumatoid arthritis, other than a short trial of massage on the juvenile forms of the disease.101

Acupuncture

A Cochrane review (2005) identified only 2 low-quality trials of acupuncture in rheumatoid arthritis, 1 of which demonstrated no benefit as compared to sham treatment. The second trial, involving electric stimulation through the needles, was suggestive of benefit for pain about the knee.102 Two systematic reviews in 2008 provided slightly different interpretations of the data available. While a Korean review concluded that there was presently no evidence to advocate the use of acupuncture,103 a US review suggested that the evidence was conflicting with some active controlled trials demonstrating favourable results for acupuncture groups, including changes in erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) measures.104

Electrical modalities and/or heat therapy

A series of Cochrane reviews have established the following facts.

Conclusion

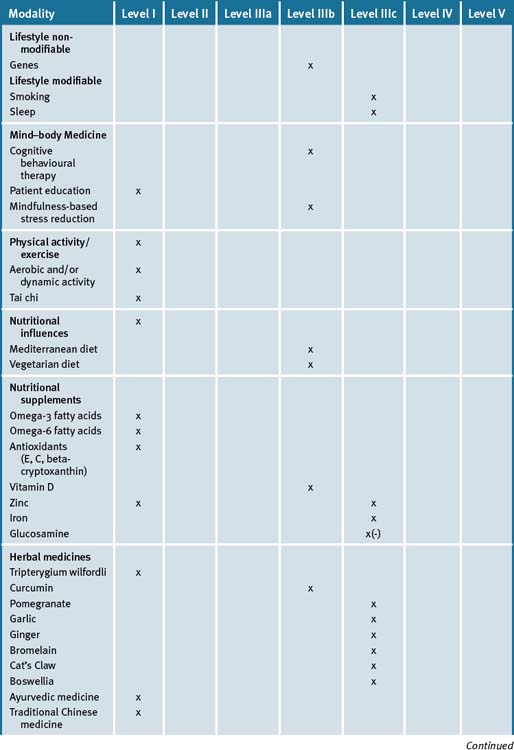

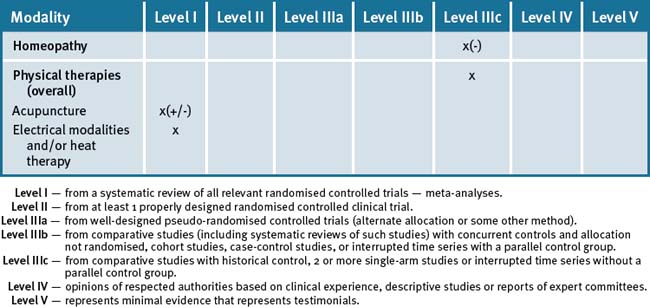

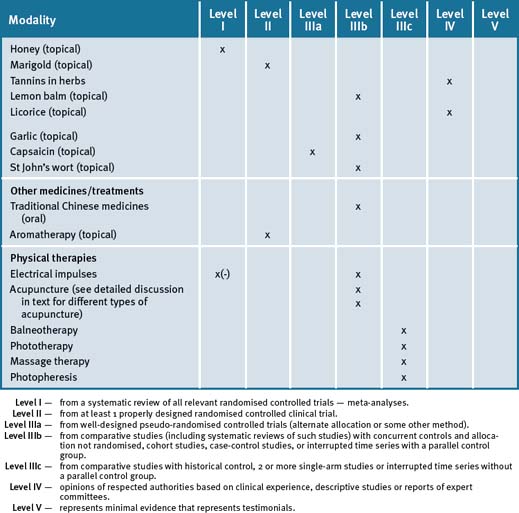

The use of an integrated approach to the management of rheumatoid arthritis would appear advantageous, particularly where treatments with proven efficacy (fish oils, evening primrose oils) may be used to reduce symptoms and, potentially, reduce the use of medications with side-effects (e.g. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). However, a note of caution would appear appropriate: given the demonstrated importance of the use of Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMAR) as early as possible to prevent future deterioration, a careful balance between pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions must be achieved in order that an over-emphasis on CAM in itself is not of detriment to the patient. Therefore, until and unless CAM therapies are proven to have a disease-modifying affect rather than symptoms minimisation alone, they should remain an adjunct to, rather than a replacement for, conventional care. Table 36.1 summarises the evidence for complementary medicine/therapies.

Clinical tips handout for patients — rheumatoid arthritis

1 Lifestyle

Sunshine

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body medicine

5 Dietary changes

6 Physical therapies

7 Supplements

Omega-3 (fish oils)

Evening primrose oil

Vitamins and minerals

Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol)

Herbal supplements

Curcumin

1 Kobayashi S., Momohara S., Kamatani, et al. Molecular aspects of rheumatoid arthritis: role of the environment. FEBS J. 2008 Sep;275(18):4456-4462.

2. Rindfleisch J.A., Muller D. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis. Am Fam Physician. 2005 Sep 15;17(6):1037-1047.

3 Sokka T., Aberson B., Pincus T. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: 2008 update. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008 Sep-Oct;26(5 suppl. 51):s35-s61.

4 Arnett F.C., Edworthy S.M., Bloch D.A., et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315-324.

5 Quinn M.A., Cox S. The evidence for early intervention Rheum. Dis Clin North America. 2005 Nov;31(4):575-589.

6 Drug O’Dell J. Therapy: Therapeutic Strategies for Rheumatoid Arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2591-2602.

7 Mimori T. Clinical significance of anti-CCP antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med. 2005 Nov;44(11):1122-1126.

8 Avouac J., Gossec L., Dougados M. Diagnostic and predictive value of anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006 Jul;65(7):845-851.

9 Vitetta L., Cicuttini F., Sali A. Alternative therapies for musculoskeletal conditions. Best Prac Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Jun;22(3):499-522.

10 Callahan L.F., Freburger J.K., Mielenz T.J., et al. Medical scepticism and the use of complementary and alternative care providers by patients followed by rheumatologists. J Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Jun;14(3):143-147.

11 Klareskog L., Alfredsson L., Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S., et al. What precedes development of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004 Nov;63(Suppl 2):ii28-ii31.

12 Klareskog L., Padyukov L., Lorentzen J., et al. Mechanisms of disease: Genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers in the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006 Aug;2(8):425-433.

13 Harel-Meir M., Sherer Y., Shoenfield Y. Tobacco smoking and autoimmune rheumatic disease. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007 Dec;3(12):707-715.

14 Vittecoq O., Lequerre T., Goeb V., et al. Smoking and inflammatory diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Oct;22(5):923-935.

15 Padyukov L., Silva C., Stolt P., et al. A gene environment interaction between smoking and shared epitope genes in HLA-Dr provides a high risk of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Oct;50(10):3085-3092.

16 Klareskog L., Padyukov L., Alfredsson L. Smoking as a trigger for inflammatory rheumatic disease. Curr Opion Rheumatol. 2007 Jan;19(1):49-54.

17 Pattison D.J., Harrison R.A., Symmons D.P. The role of diet in susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2004 Jul;31(7):1310-1319.

18 Pattison D.J., Symmons D.P., Yound A. Does diet have a role in the aetiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Nutr Soc. 2004 Feb;63(1):137-143.

19 Cerhan J.R., et al. Antioxidant micronutrients and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in cohort of older women. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:345-354.

20 Pedersen M., Stripp C., Klarlund M. Diet and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis in a prospective cohort. J Rheumatol. 2005 Jul;32(7):1249-1252.

21 Magliano M.. Obesity and arthritis. Menopause Int. 2008 Dec 14;4:149-154..

22 Muller H., de Toldedo F.W., Resch K.L. Fasting followed by vegetarian diet in patienst with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30(1):1-10.

23 Hafstrom I., Ringertz B., Spangberg A., et al. A vegan diet free of gluten improves the signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: the effects on arthritis correlates with a reduction in antibodies to food allergens. Rheumatology(Oxford). 2001 Oct;40(10):1175-1179.

24 Skoldstam L., et al. An experimental study of a Mediterranean diet for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scan J Rheumatol. 2003;62:208-214.

25 McKellar G., Morrison E., McEntegart A., et al. A pilot study of a Mediterranean-type diet intervention in female patients with rheumatoid arthritis living in areas of social deprivation in Glasgow. AnnRheum Dis. 2007;66(9):1239-1243.

26 Hyatum M., Kanerud L., Hallergren R., et al. The gut-joint axis: cross reactive food antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Gut. 2006 Sep;55(9):1240-1247.

27 Hicklin J.A., et al. The effect of diet in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Allergy. 1980;10:463.

28 Darlington L.R., Ramsay N.W. Diets for rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1991;338:1209.

29 Podas T., Nightingale J.M., Oldham R., et al. Is rheumatoid arthritis a disease that starts in the intestines? A pilot study comparing an elemental diet with oral prednisone. Postgrad Med J. 2007 Feb;83(976):128-131.

30 Hagen KB, Byfuglien M Gjeitung, Falzon L, et al. Dietary Interventions for Rheumatoid Arthritis Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1, Art. No.:CD006400

31 Davis G.C. Improved sleep may reduce arthritis pain. Holistic Nurs Prac. 2003 May-June;17(3):128-135.

32 Abad V.C., Sarinas P.S., Guilleminault C.. Sleep and rheumatologic diseases. Sleep Med Rev. 2008 Jun 12;3:211-228..

33 Labyak S.E., Bourguignon C., Docherty S. Sleep quality in children with juvenile arthritis. Holistic Nurs Prac. 2003 Jul-Aug;17(4):193-200.

34 Bourguignon C., Labyak S.E., Taibi D. Investigating sleep in disturbances in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Holistic Nurs Prac. 2003 Sep-Oct;17(5):241-249.

35 Treharne G.Y., Lyons A.C., Booth D.A., et al. Psychological wellbeing across 1 year with rheumatoid arthritis: coping resources as buffers of perceived stress. Br J Health Psychol. 2007 Sep;12(Pt 3):323-345.

36 Curtis R., Groarke A., Coughlan R., et al. Psychological stress as a predictor of psychological adjustment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Patientt Educ Couns. 2005 Nov;59(2):192-198.

37 Sharpe L., Sensky T., Timberlake N., et al. Long term efficacy of a cognitive behavioural treatment from a randomised controlled trial for patients recently diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2003;42(3):435-441.

38 Freeman K., Hammond A., Lincoln N.B. Use of cognitive behavioural arthritis education programmes in newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rehabil. 2002 Dec;16(8):828-836.

39 Riemsma R.P., Kirwan J.R., Taal E., et al. Patient education for adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2003. Art.No.: CD003688

40 Lorig K., Ritter P.L., Plant K.A. disease specific self-help program compared with a generalised chronic disease self-help program for arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Dec 15;53(6):950-957.

41 Lorig K., Ritter P.L., Laurent D.D., et al. The Internet-based arthritis self-management program: a one year randomised trial for patients with arthritis or fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Jul 15;59(7):1009-1017.

42 Hammond A., Bryan J., Hardy A. Effects of a modular behavioural arthritis education programme: a pragmatic parallel group randomised controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008 Nov;47(11):1712-1718.

43 Rhee SH, Parker JC, Smarr KL, et al. Stress Management in rheumatoid arthritis: what is the underlying mechanism? Arth Care Res 200;13(6):435–42.

44 Rau J., Ehlebracht-Konig I., Petermann F. Impact of motivational intervention on coping with chronic pain: results of a controlled efficacy study. Schmertz. 2008 Oct;22(5):575-578. 590–5

45 Wetherell M.A., Byrne-Davis L., Dieppe P., et al. Effects of emotional disclosure on psychological and physiological outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: an exploratory home-based study. J Health Psych. 2005;10(2):277-285.

46 Van Middendorp H., Sorbi M.J., van Doornen L.J., et al. Feasibility and induced cognitive emotional change of an emotional disclosure intervention adapted for home application. Patient Educ Couns. 2007 May;66(2):177-187.

47 Kelley J.E., Lumley M.A., Leisen J.C. Health effects of emotional disclosure in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Health Psychol. 1997 Jul;16(4):331-334.

48 Keefe F.J., Anderson T., Lumley M., et al. A randomized controlled trial of emotional disclosure in rheumatoid arthritis: can clinician assistance enhance the effects? Pain. 2008 Jul;137(1):164-172.

49 Zautra A.J., Davis M.C., Reich J.W., et al. Comparison of cognitive behavioural and mindfulness meditation interventions on adaptation to rheumatoid arthritis for patients with and without history of recurrent depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008 Jun;76(3):408-421.

50 Pradhan E.K., Baumgarten M., Langenberg P., et al. Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arth Rheum. 2007;57(7):1134-1142.

51 Bagheri-Nesami M., Mohseni-Bandpei M.A., Shayesteh-Azar M., et al. The effect of Benson relaxation Technique on rheumatoid arthritis patients: extended report. Int J Nurs Pract. 2006 Aug;12(4):214-219.

52 Arioloi G., Maddali Bongi S., Pappone N. The rehabilitative approach in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatismo. 2008 Oct-Dec;60(4):242-248.

53 Hammond A. Rehabilitation in rheumatoid arthritis: a critical review. Musculoskeletal Care. 2004;2(3):135-151.

54 Mayoux Benhamou M.A. Reconditioning in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2007 Jul;50(6):382-385. 377–81

55 Metsios G.S., Stavropolou-Kalinpglou A. Veldhuijzen van Zanten JJ. Rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease and physical exercise: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008 (Mar);47(3):239-248.

56 Verhagen AP, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Cardosos JR, et al. Balneotherapy for rheumatoid arthritis Cochrane Data Base of Systematic Reviews, 2003;(4):CD000518

57 Han A, Robinson V, Judd M, et al. Tai chi for treating rheumatoid arthritis Cochrane Data Base of Systematic Reviews 2004(3):CD004849

58 Lee K.Y., Jeong Oy. The effect of Tai Chi movement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2006 Apr;36(2):278-285.

59 Wang C. Tai chi improves pain and functional status in adults with rheumatoid arthritis: results of a single-blinded randomised controlled trial. Med Sport Sci. 2008;52:218-219.

60 Lee M.S., Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Tai chi for rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007 Nov;46(11):1648-1651.

61 Badsha H, Cahabra V, Leibman C, et al. The benefits of yoga for rheumatoid arthritis: results of a preliminary, structured 8 week programme. Rheumatol Int 209 Jan 31. Epub ahead of print.

62 Dash M., Telles S. Improvement in hand grip strength in normal volunteers and rheumatoid arthritis patients following yoga training Indian. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2001 Jul;45(3):355-360.

63 Stone J., Doube A., Dudson D., et al. Inadequate calcium, folic acid, vitamin E, zinc and selenium intake in rheumatoid arthritis patients: results of a dietary survey. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1997 Dec;27(3):180-185.

64 Krener J.M., Bigaouette J.. Nutrient intake of patients with rheumatoid arthritis is deficient in pyridoxine, zinc, copper and magnesium. J Rheumatol. 1996 Jun 23;(6:990-994..

65 Proudman S.M., Cleland L.G., James M.J. Dietary omega-3 fats for treatment of inflammatory joint disease: efficacy and utility. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008 May;34(2):469-479.

66 Sales C., Oliviero F., Spinella P. Fish oil supplementation in rheumatoid arthritis. Reumatismo. 2008 Jul-Sep;60(3):174-179.

67 Goldberg R.J., Katz J. A meta-analysis of the analgesic effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for inflammatory joint pain. Pain. 2007 May;129(1–2.):210-213.

68 Calder P.C. Session 3: Joint Nutrition Society and Irish Nutrition and Dietetic Institute Symposium on Nutrition and autoimmune disease; PUFA, inflammatory processes and rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008 Nov;67(4):409-418.

69 Little CV, Parsons T. Herbal therapy for treating rheumatoid arthritis Cochrane Data Base of Systematic Reviews Issue 4 CD002948

70 Belch J.J., Hill A. Evening Primrose oil and borage oil in rheumatologic conditions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(1)(Suppl):352-356. S

71 Zurier R.B., et al. Gamma linoleic acid treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised placebo controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(11):1808-1817.

72 Cerhan J.R., Saag K.G., Merlino L.A., et al. Antioxidant micronutrients and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in a cohort of older women. Am J Epidemiol. 2003 Feb 15;157(4):345-354.

73 Canter P.H., Wider B., Ernst E. The antioxidant vitamins A, C, E and selenium in the treatment of arthritis: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007 Aug;46(8):123-133.

74 Karlson E.W., Shadick N.A., Cook N.R., et al. Vitamin E in the primaty prevention of rheumatoid arthritis: the Women’s Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Nov 15;59(11):1589-1595.

75 Van Vught P.M., Rijken P.J., Rietveld A.G., et al. Antioxidant intervention in rheumatoid arthritis: results of an open pilot study. Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Jun;27(6):771-775.

76 Szodoray P., nakken G., Gaal J. The complex role of vitamin D in autoimmune diseases. Scand J Immunol. 2008 Sep;68(3):261-269.

77 Cutolo M., Otsa F., Uprus M. Vitamin D in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2007 Nov;7(1):59-64.

78 Rass P., Pakozdi A., Lakatos P. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism in rheumatoid arthritis and associated osteoporosis. Rheumatol Int. 2006 Sep;26(11):964-971.

79 Merlino L.A., Curtis J., Mikuls T.R. Vitamin D intake is inversely associated with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Jan;50(1):72-77.

80 Holick M.F. Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancer and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Dec;80(6 Suppl):1678S-1688S.

81 Milanino R., Frigo A., Bambara Lm, et al. Copper and zinc status in rheumatoid arthritis: studies of plasma, erythrocytes, and urine, and their relationship to disease activity markers and pharmacological treatment. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1993 May-Jun;11(2):271-281.

82 Wilson A., Yu H.T., Goodnough L.T., et al. Prevalence and outcomes of anemia in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Med. 2004 Apr 5;116(Suppl 7a):50S-57S.

83 Morris C.J., Earl J.R., Trenam C.W. Reactive oxygen specias and iron – a dangerous partnership in inflammation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1995 Feb;27(2):109-122.

84 Axford J.S. Rheumatic manifestations of haemochromatosis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1991 Aug;5(2):351-365.

85 Nakamura H., Masuko K., Yudoh K., et al. Effects of glucosamine administration on patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2007 Jan;27(3):213-218.

86 Matsuno H., Nakamura H., Katayama K., et al. Effects of oral administration of glucosamine-quercetin-glucoside on the synovial fluid properties in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009 Feb;73(2):288-292.

87 Soeken K.L., Miller S.A., Ernst E. Herbal medicines for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003 May;42(5):652-659.

88 Deodhar S.D., Srimal R.C. Preliminary study on antirheumatic activity of curcumin (diferuloymethane). Indian J Med Res. 1980;71:632-634.

89 Chopra A., et al. Randomized double blind trial of an ayurvedic plant derived formulation for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(6):1365-1372.

90 Shukla M., Gupta K., Rasheed Z. Consumption of hydrolysable tannins-rich promegranate extract suppresses inflammation and joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition. 2008 Jul-Aug;24(7–8.):733-743.

91 Denisov L.N., Adrianova I.V., Timofeeva S.S. Garlic effectiveness in rheumatoid arthritis. Ter Arkh. 1999;71(8):55-58.

92 Srivastava K.V., Mustafa T. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) in rheumatism and musculoskeletal disorders. Med Hypothesis. 1992;39(4):342-348.

93 Cohen A., Goldman J. Bromelain therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Pennsylvania Med J. 1964;67:27-30.

94 Mur E., et al. Randomised double blind trial of an extract from the penta-cyclic alkaloid-chemotype of uncaria tomentose for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;27(6):1365-1372.

95 Sander O., Herborn G., Rau R. Is H15(Resin extract of Boswellia serrata, “incense”) a useful supplement to established drug therapy of chronic polyarthritis? Results of a double blind pilot study. Z Rheumatol. 1998 Feb;57(1):11-16.

96 Park J., Ernst E. Ayurvedic medicine for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Apr;34(5):705-713.

97 Canter P.H., Lee Hs, Ernst E. A systematic review of randomised clinical trials of Tripterygium wilforii for rheumatoid arthritis. Phyomedicine. 2006 May;13(5):371-377.

98 Andrade L.E., Ferraz M.B., Atra E., et al. A randomised controlled to evaluate the effectiveness of homeopathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1991;20(3):204-208.

99 Gibson R.G., Gibson S.L., MacNeil A.D. Homeopathic therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: evaluation by double blind clinical therapeutic trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1980 May;9(5):453-459.

100 Fisher P., Scott Dl. A randomised trial of homeopathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001 Sep;40(9):1052-1055.

101 Field T., Hernandez-Reif M., Seligman S. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: benefits from massage therapy. J Paediatr Psychol. 1997 Oct;22(5):607-617.

102 Casimiro L, Barnsley L, Brosseau L, et al. Acupuncture and electroacupuncture for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005 Issue 4 CD003788.

103 Lee M.S., Shin B.C. Ernst Acupuncture for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008 Dec;47(12):1747-1753.

104 Wang C., de Pablo P., Chen X. Acupuncture for pain relief in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Sep 15;59(9):1249-1256.

105 Welch V, Brosseau L, Cosimiro I, et al. Thermotherapy for treating rheumatoid arthritis Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002 Issue 2 CD002826.

106 Brosseau L, Robinson V, Wells G, et al. Low level laser therapy (Classes I, II, III) for treating rheumatoid arthritis Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2000 Issue 2 CD002049.

107 Casimiro L, Brosseau L, Welch V. Therapeutic ultrasound for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002 Issue 3 CD003787.

108 Brosseau L., Judd M.G., Marchand S., et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in the hand. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2003. CD004377

109 Pelland L., Brosseau L., Casimiro L. Electrical stimulation for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2002. CD003687

110 Ergan m, Brosseau L., Farmer, et al. Splints and orthosis for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2001. CD004018.Table 36.1 Levels of evidence for lifestyle and complementary medicines/therapies in the management of rheumatoid arthritis