Rheumatoid Arthritis

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• Name significant factors related to the development of arthritis.

• Describe the etiology, epidemiology, and signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis.

• Discuss the immunologic manifestations and diagnostic evaluation of rheumatoid arthritis.

• Briefly describe juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

• Explain diagnostic procedures used in the identification and evaluation of rheumatoid arthritis.

• Analyze representative rheumatoid arthritis case studies.

• Correctly answer case study related multiple choice questions.

• Be prepared to participate in a discussion of critical thinking questions.

• Describe the principle, sources of error, clinical applications, and limitations of a rapid rheumatoid factor procedure.

Signs and Symptoms

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic, multisystemic, autoimmune disorder and a progressive inflammatory disorder of the joints (Fig. 30-1). It is, however, a highly variable disease that ranges from a mild illness of brief duration to a progressive destructive polyarthritis associated with a systemic vasculitis (Fig 30-2).The pathogenesis of RA has the following three distinct stages:

Shown are swan-neck deformity, ulnar deviation, dorsal interosseous atrophy, and swelling of wrist. (From Kaye D, Rose LF: Fundamentals of internal medicine, St Louis, 1983, Mosby.)

1. Initiation of synovitis by the primary causative factor

2. Subsequent immunologic events that perpetuate the initial inflammatory reaction

3. Transition of an inflammatory reaction in the synovium to a proliferative, destructive tissue process

Rheumatoid arthritis often begins with prodromal symptoms such as fatigue, anorexia, weakness, and generalized aching and stiffness not localized to articular structures. Joint symptoms usually appear gradually over weeks to months. The patient may display a wide variety of extra-articular manifestations (Box 30-1).

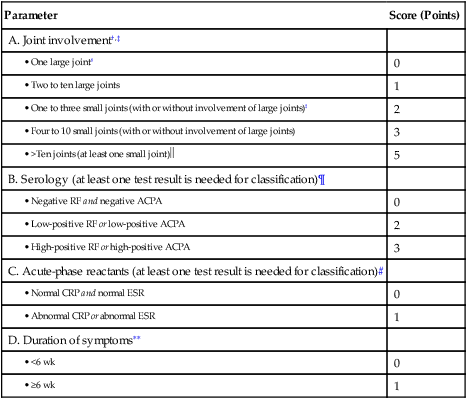

The revised American Rheumatism Association’s criteria for diagnosis of RA are presented in Table 30-1. If these conditions are present for at least 6 weeks, the patient is designated as having classic RA. Prognostic markers such as a persistently high number of swollen joints, high serum levels of acute-phase reactants of immunoglobulin M (IgM) rheumatoid factor, early radiographic and functional abnormalities, and the presence of certain HLA class II alleles may help identify patients with more severe RA who are still in the early stages of the disease.

Table 30-1

2010 ACR-EULAR Classification Criteria For Rheumatoid Arthritis∗

Adapted from American College of Rheumatology: The 2010 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis, 2011 (http://www.rheumatology.org/practice/clinical/classification/ra/ra_2010.asp).

∗The criteria are aimed at the classification of newly presenting patients. In addition, patients with erosive disease typical of RA with a history compatible with prior fulfillment of the 2010 criteria should be classified as having RA. Patients with long-standing disease, including those whose disease is inactive (with or without treatment) who, based on retrospectively available data, have previously fulfilled the 2010 criteria should be classified as having RA.

†Joint involvement refers to any swollen or tender joint on examination, which may be confirmed by imaging evidence of synovitis. Distal interphalangeal joints, first carpometacarpal joints, and first metatarsophalangeal joints are excluded from assessment. Categories of joint distribution are classified according to the location and number of involved joints, with placement into the highest category possible based on the pattern of joint involvement.

‡”Small joints” refers to the metacarpophalangeal joints, proximal interphalangeal joints, second through fifth metatarsophalangeal joints, thumb interphalangeal joints, and wrists.

§“Large joints” refers to shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, and ankles.

In this category, at least one of the involved joints must be a small joint; the others can include any combination of large and additional small joints, as well as other joints not specifically listed elsewhere (e.g., temporomandibular, acromioclavicular, sternoclavicular).

In this category, at least one of the involved joints must be a small joint; the others can include any combination of large and additional small joints, as well as other joints not specifically listed elsewhere (e.g., temporomandibular, acromioclavicular, sternoclavicular).

¶Negative refers to IU values that are ≤ to the upper limit of normal (ULN) for the laboratory and assay; low-positive refers to IU values that are higher than the ULN but ≤3 times the ULN for the laboratory and assay; high-positive refers to IU values that are >3 times the ULN for the laboratory and assay. If RF information is only available as positive or negative, a positive result should be scored as low-positive for RF.

#Normal/abnormal is determined by local laboratory standards.

∗∗Duration of symptoms refers to patient self-report of the duration of signs or symptoms of synovitis (e.g., pain, swelling, tenderness) of joints that are clinically involved at the time of assessment, regardless of treatment status.

Immunologic Manifestations

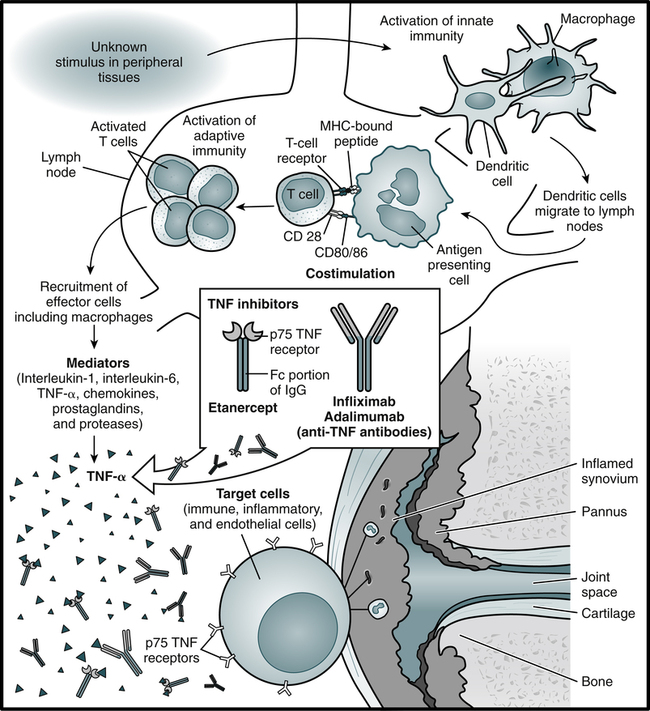

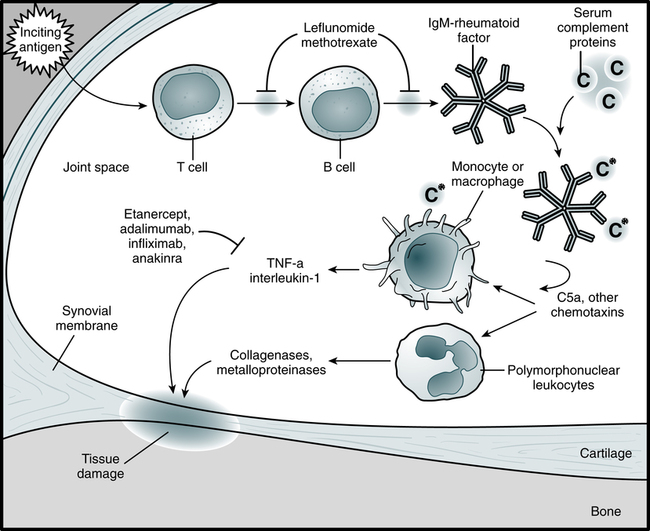

The current model of the pathogenesis of RA proposes that an infective agent or other stimulus binds to receptors on dendritic cells (DCs), which activates the innate immune system (Fig. 30-3). DCs migrate into lymph nodes and present antigen to T lymphocytes, which are activated by two signals—the presentation of antigen and costimulation through CD28. Activated T lymphocytes proliferate and migrate into the joint. Subsequently, T lymphocytes produce interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and other proinflammatory cytokines. This in turn stimulates macrophages and other cells, including B lymphocytes. B cells appear to be pivotal in the pathogenesis of RA because they can be 10,000 times as potent as DCs in presenting antigen.

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Etiology

The term juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) has fallen out of favor worldwide for a number of reasons. JRA is not, as the language implies, simply a pediatric replica of the condition that affects adults. Only about 10% of children have an arthritic disease that closely mirrors rheumatoid arthritis in adults. Researchers have concluded that the JRA category is drawn too narrowly and should include some related diagnoses, such as ankylosing spondylitis. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) can’t be used interchangeably because there are differences between the diagnoses they include (Table 30-2).

Table 30-2

Subgroups of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

| New Classification | Old Classification | Comments |

| Systemic arthritis | Systemic-onset JIA | Comprises only ≈10% of JIA cases |

| Oligoarthritis | Pauciarticular JIA | Accounts for 40% of new JIA patients |

| Polyarthritis (RF-negative) or polyarthritis (RF-positive) | Polyarticular JIA | |

| Enthesitis-related arthritis | Excluded in JIA classification, but at onset some patients in this group may be similar to late-onset pauciarticular JIA | |

| Psoriatic arthritis | Excluded in JIA classification | |

| Other | Does not fulfill criteria for any categories or fulfills criteria for more than one category | JIA is the most common type of JA but is not the only type. Other forms include juvenile lupus, juvenile scleroderma, and juvenile dermatomyositis. Children can also experience noninflammatory disorders, characterized by chronic pain associated with heredity, injury, or unknown causes. |

Adapted from Arthritis Foundation: Juvenile arthritis, 2012 (http://www.arthritis.org/juvenile-arthritis.php).

Treatment

There are several general classes of drugs (Table 30-3) traditionally used in the treatment of RA. A newer class of agents for treatment of RA, recombinant fusion proteins, selectively modulates the CD80 or CD86-CD28 costimulatory signal required for full T cell activation. Other drugs may also be used for treatment.

Table 30-3

Drugs for Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis

| Drug Type | Generic Name (Trade Name) | Example of Primary Action |

| NSAIDs | Over-the-counter NSAIDs include ibuprofen (e.g., Advil, Motrin) and naproxen (Aleve). Stronger NSAIDs are available by prescription. | The effect of NSAIDs is mainly due to their common property of inhibiting cyclooxygenases involved in the formation of prostaglandins, which leads to the normalization of an increased pain threshold. |

| Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) | Methotrexate (Trexall), leflunomide (Arava), hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), minocycline (Dynacin, Minocin) | Leflunomide inhibits pyrimidine synthesis and growth factor signal transduction nucleotide synthesis. |

| Immunosuppressants | Azathioprine (Imuran, Azasan), cyclosporine (Neoral, Sandimmune, Gengraf), cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) | Azathioprine-inhibits nucleotide synthesis; cyclosporine inhibits transcription. |

| Steroids | Prednisone | Depress natural immune system activity |

| TNF-α inhibitors | Etanercept (Enbrel), infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira), golimumab (Simponi), certolizumab (Cimzia) | Etanercept binds TNF-α and TNF-β; infliximab—chimeric anti–TNF-α antibody; adalimumab—human anti–TNF-α antibody |

| Other drugs | Anakinra (Kineret), abatacept (Orencia), rituximab (Rituxan), tocilizumab (Actemra) | Anakinra—IL-1 receptor antagonist |

Adapted from the Mayo Clinic: Rheumatoid arthritis: Treatments and drugs, 2012.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

• Azathioprine is a purine analogue that can cause severe bone marrow suppression, particularly in patients with renal insufficiency or when used concomitantly with allopurinol or angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.

• Cyclophosphamide is an alkylating agent associated with serious toxicities, including bone marrow suppression, hemorrhagic cystitis, premature ovarian failure, infection, and secondary malignancy, particularly an increased risk of bladder cancer. Thus, cyclophosphamide is not used in the treatment of uncomplicated RA.

• Cyclosporine (cyclosporin A) is an immunosuppressive agent approved for use for preventing renal and liver allograft rejection. Cyclosporine inhibits T cell function by inhibiting the transcription of IL-2.

Rapid Agglutination

Rapid Agglutination

Principle

Results

Qualitative Test Results∗

• Negative: No agglutination or color change is seen in the reagent. The reagent should have a smooth appearance against a yellow/greenish background.

• Positive: The agglutinated reagent will become visibly blue against a yellow background.

• If a positive result is obtained with the undiluted specimen, the specimen should be diluted 1:10 to determine the relationship between the level of RF present and a particular disease state.

• If the 1:10 diluted specimen demonstrates readily visible agglutination, RF is present in the specimen at a level generally associated with RA. If the undiluted specimen demonstrates agglutination and the 1:10 diluted specimen demonstrates the absence of agglutination or a fine granular background, RF is present in the specimen at a low level, which may exist in disease states other than RA.

Chapter Highlights

• Immunologic factors may be involved in the articular and the extra-articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis.

• Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic, usually progressive, inflammatory disorder of the joints, ranging from mild illness to a progressive, destructive polyarthritis associated with a systemic vasculitis.

• Two pathogenic mechanisms for RA have been hypothesized:

• The extravascular immune complex hypothesis proposes an interaction of antigens and antibodies in synovial tissues and fluid.

• An alternative hypothesis is that cell-mediated damage occurs because of accumulation of lymphocytes, primarily T cells, in the rheumatoid synovium, resembling a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction. The presence of cytokines, which affect articular inflammation and destruction, supports this hypothesis.

• Immunoglobulins can also be observed in synovial lining cells, blood vessels, and interstitial connective tissues. As many as 50% of the plasma cells that can be located in the synovium secrete IgG. The serum of most RA patients has detectable soluble immune complexes. Rheumatoid factors (RFs) have been associated with IgM, IgG, and IgA.

• Cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibodies are a highly specific and early RA indicator.

• Felty’s syndrome is RA with associated splenomegaly and leukopenia. High-titer RF, positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) assay, and rheumatoid nodules are frequently found in patients with Felty’s syndrome.

• Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is a condition of chronic synovitis, beginning during childhood.