Chapter 15 Rhesus Isoimmunization

Recognition of the Pregnancy at Risk

Recognition of the Pregnancy at Risk

ULTRASONIC DETECTION OF RH SENSITIZATION

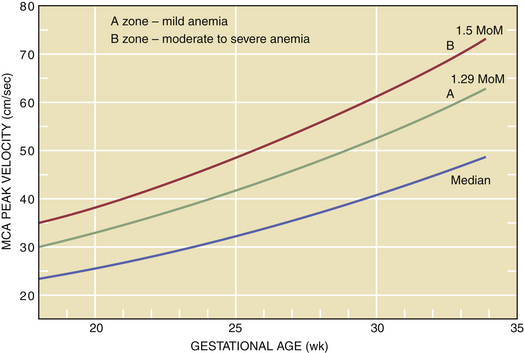

Doppler assessment of peak velocity in the fetal middle cerebral artery (MCA) in cm/sec has proved to be the most valuable tool for detecting fetal anemia. At-risk pregnancies should have this test performed every 1 to 2 weeks from 18 to 35 weeks of gestation. A fetal MCA peak systolic velocity (PSV) value above 1.5 multiples of the median for gestational age is predictive of moderate to severe fetal anemia and is an indication for percutaneous umbilical blood sampling for precise determination of fetal hemoglobin concentration. Intrauterine fetal transfusion should follow if indicated. After 35 weeks’ gestation, this test may produce a higher false-positive rate (Figure 15-1), and amniotic fluid spectrophotometry may be indicated.

AMNIOTIC FLUID SPECTROPHOTOMETRY

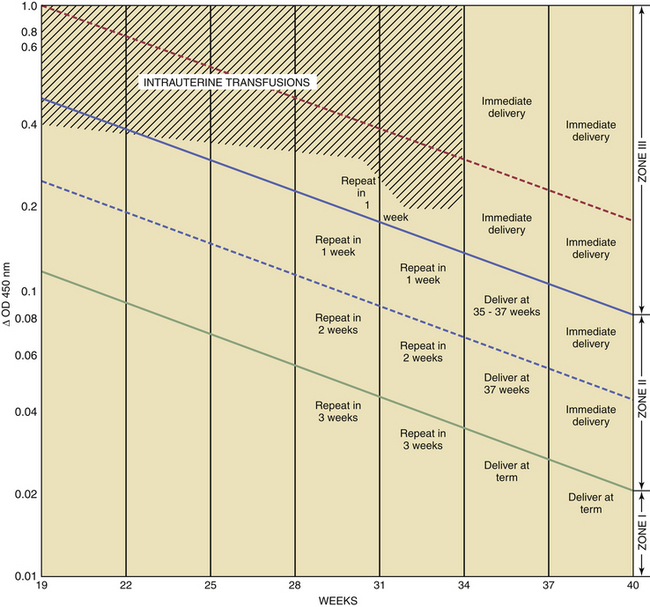

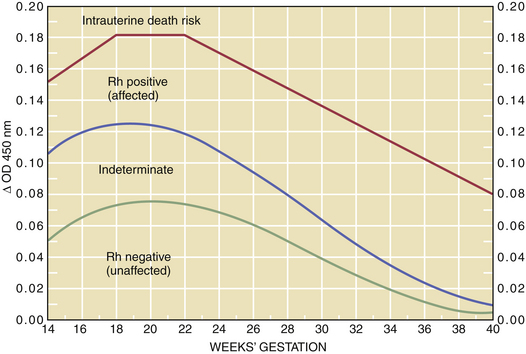

Bilirubin is normally found in amniotic fluid in a concentration that gradually diminishes toward term. For predictive interpretation, Liley devised a spectrophotometric graph based on the correlation of cord blood hemoglobin concentrations at birth and the amniotic fluid change in optical density at 450 μ. Using this method, he was able to establish predictive zones for mild, moderate, and severe disease. The Liley chart (Figure 15-2) can be used to determine, with accuracy, the severity of the disease and the appropriate management, beginning at 27 weeks’ gestation. The Queenan curve, a modified Liley curve with four zones instead of three, is used as a predictive tool in some centers from 14 to 40 weeks’ gestation (Figure 15-3). Because single ΔOD 450 values are helpful only if they are very high (zone III) or very low (zone I), serial sampling of amniotic fluid is generally indicated.

The severity of hemolytic disease in the prior pregnancy provides an approximate index for the timing of the first amniocentesis. This may range from 22 to 30 weeks with prior severe disease indicating the initial procedure as early as 22 weeks. With repeat sampling one of three trends will emerge: (1) Falling ΔOD 450 values are indicative of a fetus that is either unaffected (e.g., Rh negative) or very mildly affected. No intervention is indicated in these patients (see Figures 15-1 and 15-2). (2) If the ΔOD 450 is either stable or rising, frequent ΔOD 450 determinations are necessary to determine the timing of delivery. (3) If the ΔOD 450 enters zone III (refer to zone levels on the right side of Figure 15-2) before 34 weeks, percutaneous umbilical blood sampling is performed for determination of fetal hemoglobin followed by intrauterine transfusion if indicated.

INTRAUTERINE TRANSFUSION

Fetal Intraperitoneal Transfusion

For intraperitoneal transfusions, the volume to be infused is based on the following formula:

For example, a 30-week fetus would require a 100-mL transfusion (30 weeks − 20 × 10 = 100 mL).

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 75. Washington DC: ACOG; 2006.

Brown S., Kellner L.H., Munson M., et al. Non-invasive prenatal testing: Technical strategies to achieve testing of cell free fetal DNA (cffDNA) RHD genotype in a clinical lab. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:S173.

Howe D.T., Michailidis G.D. Intraperitoneal transfusion in severe early-onset Rh isoimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:880-884.

Mari G., Deter R.L., Carpenter R.L., et al. Noninvasive diagnosis by Doppler ultrasonography of fetal anemia due to maternal red-cell alloimmunization. Collaborative Group for Doppler Assessment of the Blood Velocity of Anemic Fetuses. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:9-14.

Mari G., Deti L., Oz U., et al. Accurate prediction of fetal hemoglobin by Doppler ultrasonography: Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:589-593.

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology Incidence

Incidence Detecting Fetomaternal or Transplacental Hemorrhage

Detecting Fetomaternal or Transplacental Hemorrhage

Timing of Delivery in the Rh-Sensitized Fetus

Timing of Delivery in the Rh-Sensitized Fetus Prevention of Rhesus Isoimmunization

Prevention of Rhesus Isoimmunization