Chapter 62 Revision uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) by Z-palatoplasty (ZPP)

1 INTRODUCTION

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) is the single most common surgical procedure performed for the correction of retropalatal obstruction causing or contributing to the obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS). Although its success rate has been reported at only 40% (when objective success is defined as a 50% reduction in the Apnea/Hypopnea Index (AHI) with a postoperative AHI of less than 20),1when appropriate patient selection criteria are applied its success rate can be as high as 80%2 (see Chapter 16: Friedman tongue position and the staging of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome).

UPPP’s effectiveness also increases dramatically when performed in combination with several adjunctive procedures that address the hypopharynx, like radiofrequency tongue base reduction.3 Many studies, however, still show a considerable failure rate.

UPPP failure is multifaceted, as is OSAHS. Causes of persistent obstruction range from morbid obesity with pan-airway obstruction to inadequate palatal resection with a variable position and amount of the remaining soft palate. A significant number of patients are often treated with a form of minimal or conservative UPPP for a variety of reasons. These patients may present with persistent or recurrent OSAHS due to a long segment of palate that causes persistent obstruction. Persistent retropalatal obstruction after UPPP has been extensively studied by several authors.4,5 Up to 75% of patients exhibit persistent obstruction localized to the level of the palate after manometric analysis of the retropalatal airway. In fact, sleep endoscopic studies on patients who had a failed UPPP procedure have shown that in 50% of patients, persistent obstruction at the retropalatal level is the cause of failure. In other cases, patients present with nasopharyngeal stenosis due to postoperative scarring.

When patients are not willing to accept CPAP as a form of permanent treatment, they often seek a surgical alternative. A modified version of UPPP for patients without tonsils, Z-palatoplasty (ZPP),6 is presented in Chapter 33. In this chapter, we present further modifications of this technique for patients requiring revision of a previously performed UPPP due to persistent or recurrent symptoms.

2 PATIENT SELECTION

Selection criteria follow the classification guidelines already described by Friedman et al.7 Patients with Friedman tongue position (FTP) III or IV must have adjunctive treatment to increase the retrolingual airway, in addition to revision palatal surgery. Candidates for revision UPPP may have had a history of previous UPPP or laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty with tonsillectomy. It is important that before undergoing UPPP revision by ZPP (as is true for all surgical procedures aimed at the treatment of OSAHS), the patient undergoes a 30-day CPAP trial, in order to document failure of this alternative as a permanent form of management, based on compliance issues. Physical exam should focus on documenting the presence of an obstruction at the level of the soft palate, and it should assess the likelihood of retrolingual obstruction by means of FTP. In addition, it should either confirm or rule out the presence of nasopharyngeal stenosis by means of fiberoptic nasopharyngolaryngoscopy and Mueller maneuver. Sleep endoscopy may provide additional evidence of persistent retropalatal obstruction.8 Even if not routinely performed, sleep endoscopy is especially valuable for evaluation of revision surgery patients. Adequate medical clearanceand a thorough review of the procedure and its complications, such as temporary velopharyngeal incompetence (VPI) and, most importantly, the risk of permanent VPI, should be conducted with the patient before obtaining consent.

3 SURGICAL TECHNIQUE (OUTLINE OFPROCEDURE)

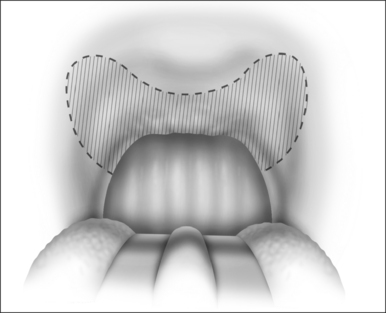

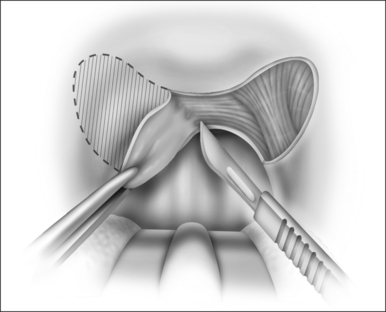

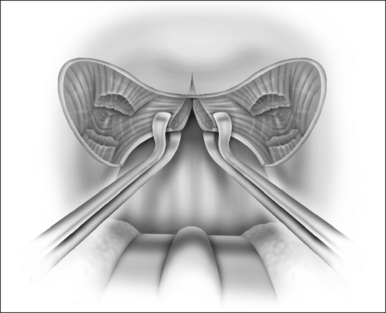

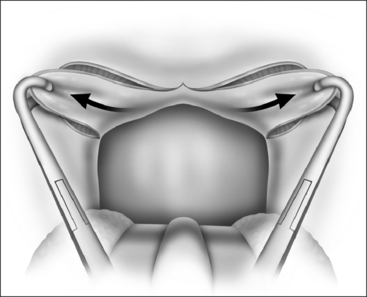

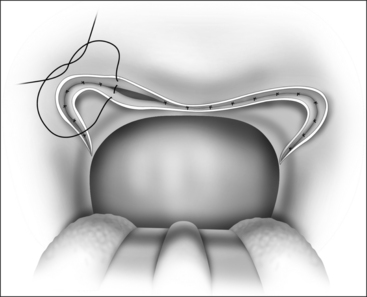

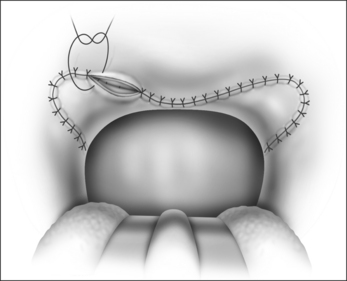

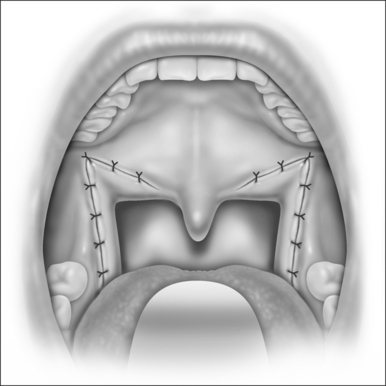

The surgical technique is illustrated in Figures 62.1–62.6. Two adjacent flaps are outlined on the palate (Fig. 62.1). The flaps for revision surgery will generally be smaller than in primary ZPP, depending on the length of the previously resected soft palate. Only mucosa of the anterior aspect of the two flaps is removed (Fig. 62.2). The two flaps are then separated from each other by splitting the palatal segment down the midline (Figs 62.3 and 62.4). A two-layered closure that brings the midline all the way to the anterolateral margin of the palate is accomplished (Figs 62.5 and 62.6). The final result creates a distance of 3–4 cm between the posterior pharynx and the palate. Additionally, the lateral dimension of the palate is usually doubled to approximately 4 cm. The exact dimensions of the flaps, which extend in a butterfly pattern, are illustrated in Figure 62.1. The anterior midline margin of the flap is halfway between the hardpalate and the free edge of ‘a normal’ soft palate. The distal margin is the free edge of the palate, and the lateral extent is posterior to the midline, and all the way to the lateral extent of the palate.

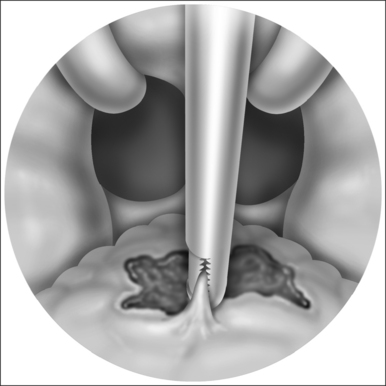

Friedman anatomical stage II and III patients concomi-tantly undergo radiofrequency tongue base reduction, based on previously published protocols.3 The Somnus Somnoplasty™ system (Gyrus ENT, Memphis, TN) double-probed hand piece with rapid lesion technique is used to deliver 600 joules to each of five sets of points outlined to the right and left of the midline, posterior to the circumvallate papillae. A total of 3000 joules (rapid lesion technique) is delivered during the procedure. Patients with residual snoring after surgery can be treated with additional tongue base reduction in the office, under local anesthesia.

4 POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT ANDCOMPLICATIONS

All patients receive preoperative antibiotics and pre- and postoperative steroids. Patients are usually discharged after one or two postoperative days, upon tolerance of a liquid or soft diet, and once pain is controlled with oral analgesics. Patients are also discharged on a tapered dose of oral methylprednisolone and antibiotics. Significant morbidity is observed in the first 24–48 hours postoperatively in the form of pain and dysphagia. Narcotic medication use averages 10 days, as does a return to normal diet.9 Immediate or delayed postoperative bleeding is rare. Airway complications after surgery in patients with OSAHS usually occur in the immediate postoperative period. Often, patients with OSAHS wake up with excellent muscle strength, and are combative and confused. If these patients are extubated before they are alert enough to follow instructions, upper airway obstruction can secondarily cause postobstructive pulmonary edema. Reintubation may be necessary but, even in the most controlled conditions, is extremely difficult. Placement of a nasopharyngeal airway can often bypass the area of obstruction and eliminate the need for reintubation. By appropriately delaying extubation until the patient is fully able to follow commands, airway complications can be avoided.

5 SUCCESS RATE OF THE PROCEDURE

5.1 SUBJECTIVE AND OBJECTIVE SYMPTOM ELIMINATION

Subjective success is based on comparative improvements in snoring levels, from both the patient’s and the bedpartner’s perspective, as well as on overall daytime sleepiness and well-being. When comparing snoring levels and ESS scores obtained before the original UPPP with data obtained after revision ZPP in a series of 31 patients, Friedman et al. found statistically significant improvement in both para-meters. When applying strict criteria of snoring improvement (that is 50% decrease in snoring level with a postoperative snoring level of 5), improvement was found in 100% of the patients.9 Quality of life parameters were also significantly improved in all eight domains of the validated SF-36v2™ Health Survey (QualityMetric, Lincoln, RI) assessment tool, which is translated into an improvement in physical functioning, role limitation as a result of physical health problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitation as a result of emotional problems, and mental health.

When focusing on objective success, ZPP shows considerable improvement over UPPP. Objective cure rates based on polysomnographic data consistently show improvement in the mean values of delta and REM sleep, as well as improvement in the Apnea Index, Apnea/Hypopnea Index, and minimum oxygen saturation. Using the classic definition of objective cure proposed by Sher et al.1 (50% reduction in AHI, with a final postoperative value of less than 20), 68% of patients had successful treatment of their OSAHS, and none of the remaining 32% worsened with the revision procedure.

5.2 WHAT TO DO IF THE PROCEDURE FAILS

Failure in this procedure, as in any other procedure, can be defined as the persistence of symptoms. Failure also occurs when symptoms of snoring and daytime sleepiness are eliminated but polysomnographic data indicate persistent disease, often with a pattern of elimination of apneas, but with persistent hypopneas. Sleep endoscopy is a valuable tool for assessing failure, and should be performed to identify the anatomic site of persistent obstruction. Failure in achieving satisfactory results requires the resumption of CPAP therapy by the patient. Other surgical options for patients unwilling to accept CPAP as a permanent form of management include techniques that focus on the hypopharynx, like genioglossal advancement, thyrohyoid suspension, hyomandibular suspension, and tongue base suspension. Salvage surgery in the form of maxillomandibular advancement, as described by Li et al.,10 is likely the best option, due to its expanding effect on the entire upper airway. Transpalatal advancement pharyngoplasty may be considered if retropalatal obstruction persists.11

1. Sher AE, Schechtman KB, Piccirillo JF. The efficacy of surgical modifications of the upper airway in adults with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1996;19:156-177.

2. Friedman M, Vidyasagar R, Bliznikas D, et al. Does severity of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome predict uvulopalatopharyngoplasty outcome? Laryngoscope. 2005;115:2109-2113.

3. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Lee G, et al. Combined uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and radiofrequency tonguebase reduction for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:611-621.

4. Woodson B, Wooten M. Manometric and endoscopic localization of airway obstruction after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111:38-43.

5. Metes A, Hoffstein V, Mateika S, et al. Site of airway obstruction in patients with obstructive sleep apnea before and after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:1102-1108.

6. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Vidyasagar R, et al. Z-palatoplasty (ZPP): a technique for patients without tonsils. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:89-100.

7. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Joseph N. Staging of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome: a guide to appropriate treatment. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:454-459.

8. Pringle M, Croft C. A grading system for patients with obstructive sleep apnoea – based on sleep nasendoscopy. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1993;18:480-484.

9. Friedman M, Duggal P, Joseph N. Revision uvulopalatoplastyby Z-palatoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:638-643.

10. Li K, Riley R, Powell N, et al. Maxillomandibular advancement for persistent obstructive sleep apnea after phase I surgery in patients without maxillomandibular deficiency. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1684-1688.

11. Woodson B, Toohill R. Transpalatal advancement pharyngoplasty for obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:269-276.