Chapter 8 Review

Defining review

Review, or evaluation, is defined as ‘attributing value to an intervention by gathering reliable and valid information about it in a systematic way, and by making comparisons, for the purposes of making more informed decisions or understanding causal mechanisms or general principles’.1 The term is also described as ‘a deliberate, systematic process in which a judgement is made about the quality, value or worth of something by comparing it to previously identified criteria or standards’ (emphasis in the original).2 In other words, review is a systematic process that uses valid and reliable instrumentation to quantify changes in a parameter in order to facilitate decision making. In clinical terms, review determines whether a client’s presenting condition or state of imbalance improved after the delivery of care, which factors attributed to the client’s outcome, whether the client moved towards expected outcomes or goals, whether the interventions were safe and effective, and whether the underlying cause of the complaint had been resolved.3–5 Review can thus be likened to the evidence-based practice process in that the best available information on the client is gathered and appraised in order to inform practice. Research is another useful analogy, with the planning phase of care being akin to the generation of a hypothesis or expected outcome, and the review phase involving the testing of that expected endpoint.6

The importance of review

Increasing demand for quality healthcare and evidence-based practice7,8 suggests that CAM providers can no longer discount the evaluation of client care. As well as the increase in public pressure, the review of practice is also being driven by a need to quantify client outcomes, CAM practitioner performance and healthcare efficiency. This review of healthcare interventions and client outcomes not only provides useful feedback to improve the quality of care,9,10 but by measuring the efficacy, cost-effectiveness and timeliness of healthcare,3 can also provide essential data to improve the delivery of CAM services and to benchmark against best practice. The purposeful ongoing appraisal of client outcomes before, during and/or after each client appointment, for example, may promptly identify delays in the achievement of expected outcomes (by comparing actual progress against expected progress) and thus more effectively determine if a treatment needs to be modified or altered to better meet client needs and to deliver best practice care. The review of practice may also reduce treatment costs and client suffering by highlighting interventions that are neither safe nor useful11 and, in some cases, determine if referral to another healthcare professional, either within or outside the integrative healthcare team, is needed. Put simply, the appraisal of CAM practice may improve the quality of client care by determining whether clinical outcomes have been achieved in the most beneficial, efficient and cost-effective manner.7,10

Practitioners who use review techniques may over time contribute significantly to the professional advancement of CAM. The evaluation of practice, for instance, encourages new ways of thinking and practising,12 which, in turn, filters useful knowledge back into the profession.9 This knowledge could help to improve personal and professional standards,10 create new benchmarks for best practice care, and through subsequent improvements in client outcomes and client satisfaction, generate a more widely accepted, client-centred and ethically sound profession.

From the perspective of the clinician, practice review ensures that CAM practitioners maintain a sense of accountability for care given.3 In other words, by self-appraising performance, competence, knowledge, experience and decision-making ability, a practitioner can identify areas for personal and professional development and thereby improve client care.5,12,13 Given that CAM practitioners have a duty to deliver high-quality best practice care to all individuals, the importance of self-appraisal cannot be overemphasised.

From an ethical point of view, the critical appraisal of client outcomes provides some assurance that clinicians practise in a beneficent and non-maleficent manner. Nevertheless, for individual benefits to be seen, CAM practitioners need to not only measure the outcomes of care, but also to change practice when indicated.10 Thus, review requires not only critical thinking and client interaction, but also action.

Practice review can also create mutual benefits for clinician and client. Fundamentally, evaluation provides useful information that facilitates shared decision making9,14 and ameliorates client–practitioner communication.7 These outcomes could lead to improvements in client rapport, which may further improve client health and wellbeing, and the efficiency of CAM services.15

Strategies for reviewing practice

The review of clinical practice often requires a number of tools or outcome measures to effectively answer the clinical questions posed.7 The use of multiple assessment methods is particularly important, including approaches that generate quantitative and qualitative data, to ensure that observer bias is minimised and practitioner confidence in findings can be increased.16 Yet there is a limited number of freely available evaluation tools, with demonstrated validity and reliability, that can effectively review client outcomes in a clear, concise and quantifiable manner. Where suitable instruments are available, client outcomes should be evaluated using the same tools that were used during assessment3 in order to improve the validity of inferences made about the efficacy of treatment17 (see chapter 3).

Even though these evaluation instruments are useful in the review process, they are not the only source of information that can be drawn upon. CAM practitioners can, for instance, monitor the effectiveness of treatment through client interviews, physical assessment,18 medical imaging and/or functional, pathology, invasive and miscellaneous tests. Client self-reporting through questionnaires and diaries is also adequate for monitoring and evaluating client outcomes and clinical progress.7,19 As such, data for client review can be derived from a number of sources, including the client, family, caregivers, pertinent documentation, questionnaires, literature, other healthcare professionals, observations and objective measures such as blood pressure monitoring and pathology testing. Hence, depending on the type of data required and the timing of expected outcomes, information may be collected for review before, during and/or after client consultation. Other instruments that can be used to monitor individual progress are listed in Table 8.1.

While the sourcing of accurate and reliable data is important to the review process, it is only one of many considerations that need to be taken into account. An effective clinical review also requires CAM practitioners to be mindful of the factors that facilitate and impede the attainment of client outcomes (see Table 8.2). The achievement of these outcomes can, for example, be affected by the choice of intervention, the client–practitioner relationship and the treatment philosophy adopted by the clinician.9,15 Social factors, such as environment,18 family, culture, religion, language and education, can also influence the rate of progress towards defined clinical endpoints. A person with poor English proficiency or health literacy, for instance, may have difficulty understanding what is communicated by their clinician, including pertinent information about the disease process, complications of the condition and the management of their complaint. These difficulties could result in lower levels of knowledge and, consequently, poorer outcomes of care. The positive relationship between English fluency and diabetes knowledge scores reported in the Fremantle diabetes survey lends support to this claim.20

Table 8.2 Factors affecting the attainment of client outcomes or client adherence to treatment

| Age | Attitude to illness, treatment or practitioner | Availability/access to services and treatments |

| Chronicity/severity of presenting complaint | Chronicity, duration and number of comorbidities | Client–practitioner rapport |

| Client preference, expectations and faith in treatment | Client satisfaction with treatment | Complexity and safety of treatment |

| Culture and ethnicity | Educational attainment | Family influence and commitments |

| Financial constraints | Functional ability | Gender |

| Health literacy | Information about treatment | Level of follow-up or client review |

| Memory retention and recall | Motivation | Perceived health status |

| Physical and/or intellectual disability | Practitioner communication skills | Proficiency of local language |

| Psychiatric illness | Readiness to change | Religion |

| Support structure | Work commitments |

Equally important are the client-derived factors, including age, gender, functional ability, cognitive capacity, motivation, perceived health status, preference for treatment, readiness to change and treatment expectation. A person who has poor memory retention and recall, Alzheimer’s disease for instance, may have difficulty adhering to a treatment plan and, as a result, may not receive optimal care. This may also be the case for clients suffering from depression, anxiety, or a physical or intellectual disability.

The review of practice also needs to appreciate the impact structural factors, such as the environment, resources and administrative and collegial support, have on client progress.21 Product recalls, delivery delays, equipment failure and the absence of local health services or resources are just some examples of the many structural factors that can interfere with clinical progress.

Judicious consideration of process factors such as the coordination of services, collaboration, professionalism, interpersonal skills, clinician sensitivity, treatment compliance, waiting time, evidence-based practice and client education is also needed.21 Indeed, any factor influencing treatment compliance is likely to affect client outcomes. Thus, changing an intervention when a client fails to meet a defined clinical endpoint may be premature if other factors influencing client outcomes have not been considered first. The questions listed in Table 8.3 take a number of these factors into account when evaluating client outcomes.

Table 8.3 Questions for reviewing clinical practice

|

• Was the assessment method valid, reliable and sensitive enough to detect changes in client outcomes?

|

Brownie;12 Crisp & Taylor;3 Leach;22 Long;17 Murray & Atkinson23

Another element that can hamper client progress is misdiagnosis. Two factors that might contribute to an incorrect diagnosis are inadequate diagnostic reasoning and/or insufficient clinical assessment, but by reassessing the client and revisiting the CAM diagnoses, aetiological factors, goals, expected outcomes and treatments, a practitioner can utilise the review process to identify and resolve misdiagnosis early.3,5,18 An accurate diagnosis and the timely achievement of expected treatment outcomes (i.e. reaching the outcome by the predetermined date) can also be influenced by practitioner attitude, knowledge and skill.4 The effect these attributes have on client outcomes can be identified and managed using reflective practice.

Reflective practice

Rolfe, Freshwater and Jasper24 define reflective practice as a rational and conscious process of systematically and rigorously reflecting on one’s practice to challenge existing approaches and to learn from one’s actions. Reflective practice is an effective lifelong learning tool that brings theory and practice closer together,6,25 which, in accordance with the principles of evidence-based practice,26 promotes safe, knowledgeable and informed care.27 Reflective thinking also fosters an individualised, ethical, holistic and flexible approach to client care.28 As well as meeting client needs more effectively, reflection also improves the quality of care7 by identifying overlooked aspects of assessment, planning and treatment,29 and by modifying practitioner decision making and performance.30

Reflection is an insightful strategy for which practitioners can view and approach situations from alternative perspectives to determine if the same approach would be repeated or changed if done again.13,31,32 Without this insight, it is uncertain whether healthcare practices and client outcomes would improve.30 Hence, reflection provides a means to evaluate performance, improve clinical competence and credibility, extend the scope of practice and aid the ongoing development of the CAM profession.13,25,29,33

A number of earlier studies have suggested that reflective strategies might improve clinical practice34 and professional development.13 Even so, there is still a paucity of evidence linking reflective thinking to positive clinical outcomes.35,36 Sound clinical research is needed to investigate not only the potential benefits of reflective practice, but also the validity, reliability and sensitivity of useful review instruments.

Despite concerns regarding the subjectivity of reflective thinking, reflection does challenge ‘the constraints of habituated thoughts and practices’,37 and furthermore, provides insight into the beliefs, values, assumptions, culture, history, theories, knowledge and practices that shape those decisions.12,29,33 Questions that can facilitate reflective practice or introspective enquiry are listed in Table 8.4.

Adapted from Murray & Atkinson.23

The review process

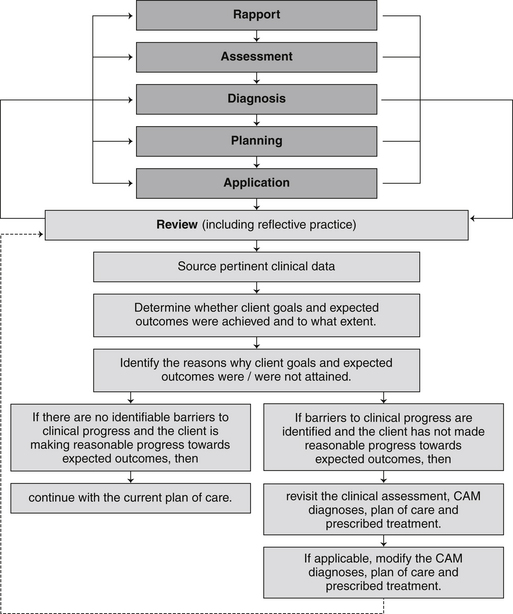

As alluded to thus far, there are a number of important considerations when reviewing client care. Reflective and critical thinking, best available evidence, systematic clinical assessment and clinical expertise are just some of these core elements. These attributes are no different than those required at every other stage of DeFCAM. This is because review spans across all stages of the decision-making process and is not restricted to the last and final stage of DeFCAM. Therefore, even though review plays a fundamental role in follow-up care, particularly in determining the safety and efficacy of prescribed treatment, and the degree to which a client has progressed towards planned goals and time-limited expected outcomes, it also informs clinical assessment, diagnostic reasoning, planning and the course of treatment. This relationship between review and other stages of DeFCAM is further illustrated in Figure 8.1.

Figure 8.1 also shows how a CAM practitioner can actively participate in the review process and how they should respond when a client is or is not making reasonable progress towards expected outcomes. If, for example, a client originally presenting with arthralgia (secondary to osteoarthritis) demonstrated a twenty-five per cent improvement in bilateral knee pain after 2 weeks and the short-term expected outcome was a fifty per cent reduction in the severity of bilateral knee pain within 4 weeks, then the client would have made adequate clinical progress and the current plan of care should continue. If the client made no progress or knee pain worsened, then the practitioner should reassess the client to ascertain whether any pertinent data were overlooked during clinical assessment (e.g. joint laxity was not assessed), if the CAM diagnosis was accurate (the diagnosis ignored the impact of diet on osteoarthritis), whether the goals, expected outcomes and treatment were appropriate (e.g. the management plan did not incorporate local pain relief) and if there were any factors that may have affected client adherence to treatment or achievement of outcomes (e.g. recent cold weather exacerbated the arthralgia). If any of these issues are identified, the practitioner should employ measures to resolve the problem, where appropriate modify the treatment plan, and then review client progress again at the next follow-up visit.

Summary

Learning activities

1. Ovretveit J. Evaluating health interventions. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1998.

2. Wilkinson J.M. Nursing process in action: a critical thinking approach. Redwood City: Addison-Wesley Nursing, 1992.

3. Crisp J., Taylor C. Potter and Perry’s fundamentals of nursing, 3rd ed. Sydney: Elsevier Australia; 2008.

4. Harkreader H., Hogan M.A., Thobaben M. Fundamentals of nursing: caring and clinical judgement, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2007.

5. Kulkarni K., et al. American dietetic association: standards of practice and standards of professional performance for registered dieticians (generalist, specialty, and advanced) in diabetes care. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105(5):819-824.

6. Wilkinson J.M. Nursing process and critical thinking, 4th ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall; 2007.

7. Marshall S., Haywood K., Fitzpatrick R. Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: a structured review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2006;12(5):559-568.

8. Shortell S.M., Rundall T.G., Hsu J. Improving patient care by linking evidence-based medicine and evidence-based management. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(6):673-676.

9. Long A. Outcome measurement in complementary and alternative medicine: unpicking the effects. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2002;8(6):777-786.

10. Lynn J., et al. The ethics of using quality improvement methods in healthcare. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;146(9):666-673.

11. Green J., South J. Evaluation. New York: McGraw-Hill International; 2006.

12. Brownie S. The role of reflective practice in case management. Journal of the Australian Traditional-Medicine Society. 2003;9(3):133-135.

13. Gustafsson C., Fagerberg I. Reflection, the way to professional development? Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2004;13(3):271-280.

14. Smith N.L. Fundamental issues in evaluation. In: Smith N.L., Brandon P.R., editors. Fundamental issues in evaluation. New York: Guilford Press, 2007.

15. Leach M.J. Rapport: a key to treatment success. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2005;11(4):262-265.

16. Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation. The personnel evaluation standards: how to assess systems for evaluating educators, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press; 2008.

17. Long A., Mercer G., Hughes K. Developing a tool to measure holistic practice: a missing dimension in outcomes measurement within complementary therapies. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2000;8:26-31.

18. Craven R.F., Hirnle C.J. Fundamentals of nursing: human health and function, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

19. Eastwood C.A., et al. Weight and symptom diary for self-monitoring in heart failure clinic patients. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2007;22(5):382-389.

20. Bruce D.G., et al. Diabetes education and knowledge with type 2 diabetes from the community: the Fremantle diabetes study. Journal of Diabetes and Complications. 2003;17:82-89.

21. Byers J.F., Brunell M.L. Demonstrating the value of the advanced practice nurse: an evaluation model. AACN Clinical Issues. 1998;9(2):296-305.

22. Leach M.J. Revisiting the evaluation of clinical practice. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2007;13(2):70-74.

23. Murray M.E., Atkinson L.D. Understanding the nursing process in a changing care environment, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000.

24. Rolfe G., Freshwater G., Jasper D. Critical reflection for nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave; 2001.

25. Lachman N., Pawlina W. Integrating professionalism in early medical education: the theory and application of reflective practice in the anatomy curriculum. Clinical Anatomy. 2006;19(5):456-460.

26. Roberts A.E.K. Advancing practice through continuing professional education: the case for reflection. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002;65(5):237-241.

27. Williams G., Lowes L. Reflection: possible strategies to improve its use by qualified staff. British Journal of Nursing. 2001;10(22):1482-1488.

28. Gustafsson C., Asp M., Fagerberg I. Reflective practice in nursing care: embedded assumptions in qualitative studies. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2007;13(3):151-160.

29. Donaghy M., Morss K. An evaluation of a framework for facilitating and assessing physiotherapy students’ reflection on practice. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2007;23(2):83-94.

30. Price A. Encouraging reflection and critical thinking in practice. Nursing Standard. 2004;18(47):46-52.

31. Clarke K.A. Maslow: hierarchy of needs – or reflective framework? Nurse 2 Nurse Magazine. 2004;4(2):27-28.

32. O’Connor A. Clinical instruction and evaluation: a teaching resource, 2nd ed. Sudbury: Jones & Bartlett; 2006.

33. Murphy L. Enriching practice through reflection: an exemplar. Vision. 2002;8(14):16-19.

34. Page S., Meerabeau L. Achieving change through reflective practice: closing the loop. Nurse Education Today. 2000;20:365-372.

35. Duffy A. A concept analysis of reflective practice: determining its value to nurses. British Journal of Nursing. 2007;16(22):1400-1407.

36. Schutz S. Reflection and reflective practice. Community Practitioner. 2007;80(9):26-29.

37. Wilkinson J. Implementing reflective practice. Nursing Standard. 1999;13(21):36-40.