Chapter 23 Reverse abdominoplasty

• Tensioned reverse abdominoplasty (TRA) is not suitable for all patients, nor is it a substitute for conventional abdominoplasty.

• The greatest benefit of TRA is the possibility of treating deformities of the superior abdominal wall by using a direct approach to the region. This avoids using conventional abdominoplasty techniques to treat deformities located primarily at the upper abdomen.

• TRA is a simple, fast and easy technique that can be applied in association with other procedures, such as mini-abdominoplasty, liposuction, reduction mammoplasty, and augmentation mammoplasty – either by using prostheses or by means of retromammary insertion of dermal-fat flaps that would be resected from the most cephalic portion of the abdominal flap.

• Flap fixation to the aponeurosis drastically reduces the incidence of seroma formation. The upper traction of the flap reshapes the upper abdomen and distributes its supporting forces across the abdominal aponeurosis. This principle reduces tension on the resulting scar, favoring its quality and preventing postoperative displacement of the new mammary sulcus.

Introduction

The first description of skin and adipose tissue resection in the upper abdomen was made by Thorek in 1942.1 However, in 1977 Rebello & Franco described and systematized the approach through the inframammary sulcus for abdominal plastic surgery.2 After this period, reverse abdominoplasty was practically forgotten about for many years. This was primarily because it was said to result in poor esthetic results with regards to the inframammary scars.3

This chapter proposes a modification of the original technique, based on the upper traction of the flap and its strong fixation to the abdominal aponeurosis, resulting in a tension-free inframammary scar.4 The inframammary scar extension and the dissection amplitude are determined by the intensity of the supraumbilical deformities.

Preoperative Preparation

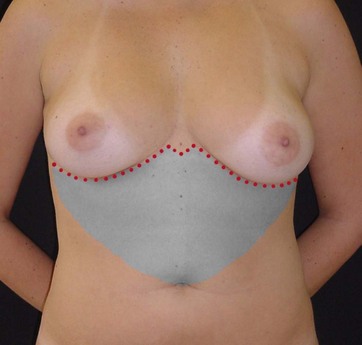

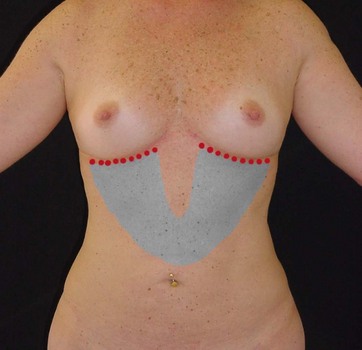

• Group 1: Larger amounts of skin to be resected require incision unification at the midline. In this group, the flap is dissected towards the umbilical scar, forming a single U-shaped tunnel (Fig. 23.1).

• Group 2: These patients have little or moderate supraumbilical skin laxity and no diastasis of the abdominal wall. The incisions will be limited to the inframammary regions, without unification at or crossing the midline. The flap dissection will produce two oblique tunnels towards the umbilical scar. The width of each tunnel will be determined by the breast width; and each tunnel joins the contralateral portion halfway between the inframammary sulcus and the umbilical scar (Fig. 23.2).

Surgical Technique

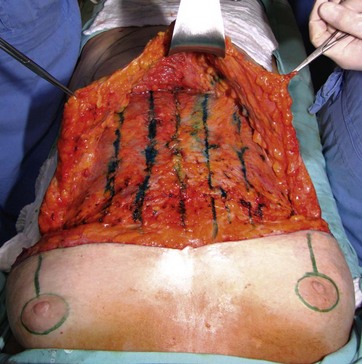

The flap to be dissected should be infiltrated with saline solution and epinephrine, at a concentration of 1 : 500 000. Epinephrine (1 mg) is used for each 500 ml of saline. The amount varies depending on the extension of the area to be treated and the patient’s measurements. One liter is needed for the entire abdominal surface, and about 500 ml for just the superior half are usually used. In cases of excessive fat, the procedure begins with a liposuction, which can be limited to the flap region or include the entire abdominal wall.5 In both groups, dissection is performed with electrocautery at the anterior aponeurotic plane, resulting in one or two dermal-fat flaps (Fig. 23.3).

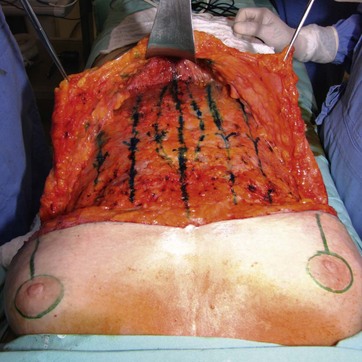

FIG. 23.3 Dissected flap showing traction lines and the midline fascia plication markings in methylene blue.

If indicated, supraumbilical plication of the abdominal fascia at the midline is performed, with monofilament nylon threads in two planes. The first aponeurotic suture is done with single interrupted sutures of 2–0 nylon monofilament (Fig. 23.4). The second line of suture is accomplished with a continuous suture of 3–0 nylon monofilament (Fig. 23.5).

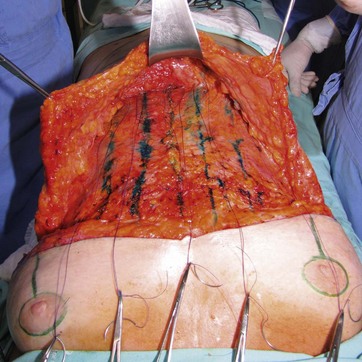

After performing the dissection and muscle plication based on individual requirements, the principle of progressive and continuous tension sutures is applied towards the inframammary incision (Fig. 23.6).6,7 The location of traction lines is marked with methylene blue, with each suture intended to perform superior traction on the flap.

Polygalactine 2–0 threads with a 4 cm needle are used for flap fixation and traction. The surgeon or the assistant should pull the flap towards the incision, in such a way that each stitch determines a superior traction of the flap as a supporting maneuver for flap cranial progression (Fig. 23.7). The suture should include Scarpa’s fascia, but avoid getting close to the dermis as, although the threads are absorbable and the skin depressions will spontaneously disappear, external notches take a long time to fade and can be distressing to patients.

In Group 1 patients with larger dissections with a single flap, after flap traction and fixation, the dermal-fat excess is divided at the midline and symmetrically resected (Fig. 23.8).

For the sake of preserving the submammary sulcus, it is very important to perform a deep flap fixation using polygalactine 2–0 thread, a second plane of subcutaneous sutures with polygalactine 3–0 thread and a final intradermal suture with polygalactine 4–0 thread (Fig. 23.9). In cases of incision unification at the midline, the scar is M-shaped to minimize risks of hypertrophic scars and scar retractions (Figs 23.10 and 23.11). In cases with persistent skin excess in the lower abdomen, resections can be performed with limited dissection, as done in mini-abdominoplasty. No drain placement is performed.

Optimizing Outcomes

• We use the navel as the inferior limit of dissection in almost all cases. Even so, due to intense upper traction of the flap, it is possible to observe reduced skin redundancy in the infraumbilical segment as well. Nevertheless, the inferior dissection can be carried further down, releasing the umbilical scar and enabling midline plication along the whole extension of the abdominal fascia, as originally proposed by Rebello and Franco.2 This procedure is considered safe, once vascularization will be kept by preserved lateral perforating and inferior epigastric arteries.

• We prefer a modification of the tension suture method – continuous and with guiding lines. Continuous sutures make the procedure easier and faster, but we understand that the technique can also be performed with separated stitches, without affecting the final result.

• In Group 2, when performing resections with limited mammary sulcus incisions, we frequently need to associate TRA with mini-abdominoplasty to have good esthetic results. In this way, TRA performs upper traction of the abdominal wall and mini-abdominoplasty performs lower traction towards the pubis.

• The adequate reconstruction of the inframammary sulcus is extremely important for the final result. The incision is sutured in three planes, with the deeper sutures fixed to the aponeurosis for a better definition of the mammary sulcus position. When performed as described above, the flap is fixed to the abdominal wall and does not tend to displace caudally to its initial position. This procedure minimizes the tension on the resulting scar and prevents the inframammary sulcus or breasts displacement. We always try to keep the inframammary sulcus at its original position.

Postoperative Care

1 Avelar JM. Upper abdominoplasty without panniculus undermining and resection. São Paulo: Editora Hipócrates; 2002.

2 Rebello C, Franco T. Abdominoplasty through a submammary incision. Int Surg. 1977;62(9):462–463.

3 Hakme F, Freitas RR, Souza BA. Historical evolution of abdominoplasty. In: Avelar JM, ed. Abdominoplasty: Without Panniculus Undermining and Resection. São Paulo: Editora Hipócrates, 2002.

4 Deos MF, Arnt RA, Gus EI. Tensioned reverse abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:2134.

5 Matarasso A. Liposuction as an adjunct to a full abdominoplasty revisited. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(5):1197–1202.

6 Pollock H, Pollock T. Progressive tension sutures: a technique to reduce local complications in abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(7):2583–2586.

7 Pollock T, Pollock H. Progressive tension sutures in abdominoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2004;31(4):583–589.