Chapter 36 Retrolabyrinthine and Retrosigmoid Vestibular Neurectomy

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Surgical intervention is indicated when medical treatments and dietary adjustments fail to control spontaneous episodic vertigo of labyrinthine origin. The most common diagnosis in such patients is Meniere’s disease. Delayed secondary endolymphatic hydrops may result from other types of inner ear disorders or injuries. Sometimes, ongoing vestibular symptoms after vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis may be treated surgically, although surgical results in these settings are less predictable.1

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The first vestibulocochlear nerve section was performed in 1898 by Krause,2 and the first posterior fossa vestibulocochlear nerve section for the treatment of vertigo in a patient with Meniere’s disease was performed by Frazier in 1904.3 McKenzie4 was the first to perform selective division of the superior half of the vestibulocochlear nerve in 1931. This procedure was popularized by Dandy, who first sectioned the vestibulocochlear nerve in 1925, and later began performing selective vestibular neurectomies in 1932. Dandy eventually performed 624 vestibular neurectomies; half of these patients underwent selective vestibular neurectomy.5 This series of patients is impressive not only because of the large number of patients, but also because the procedures were performed without microscopic assistance and modern antibiotics. With Dandy’s death in 1946, vestibular neurectomy was largely replaced by peripherally destructive procedures. Although highly successful in treating vertigo, residual hearing was compromised with these procedures.

The first microsurgical division of the vestibular nerve was performed in 1961 by House6 through a middle cranial fossa approach; this approach was modified further by Fisch7 and Glasscock.8 The middle cranial fossa approach allows the surgeon to identify and section selectively the vestibular nerve within the internal auditory canal (IAC). The procedure is technically challenging, however, and has a high incidence of postoperative facial nerve weakness and deafness.

The retrolabyrinthine approach for division of the trigeminal nerve was described by Hitselberger and Pulec in 1972,9 and in 1978, Brackmann and Hitselberger reported treatment of vertigo and tic douloureux by selective division of the vestibular and trigeminal nerves via a retrolabyrinthine approach.10 Silverstein and Norrell11 noted a clear cleavage plane between the cochlear and vestibular nerve fibers while resecting a ninth cranial nerve neurilemmoma via a retrolabyrinthine approach, and suggested that selective vestibular neurectomy was feasible in this fashion. Silverstein’s subsequent reports12,13 on the success of retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section in eliminating vertigo, while avoiding facial nerve damage and hearing loss, ushered in a new era for selective vestibular neurectomy.

The success and increasing popularity of the retrolabyrinthine approach to vestibular neurectomy in the 1980s led to efforts to improve the technique further. In an effort to prevent cerebrospinal fluid leak, which was caused by difficulty reapproximating the dura anterior to the sigmoid sinus, many surgeons adopted a retrosigmoid approach for vestibular neurectomy. This approach also allows division of the nerve more laterally in the cerebellopontine angle cistern, where identification of the vestibulocochlear cleavage plane may be easier. The retrosigmoid procedure can be extended in some cases to include drilling of the posterior IAC, allowing visualization of the intracanalicular portion of the nerve; this may be helpful in cases where the nerve bundles cannot be distinguished within the posterior fossa. In an effort to avoid problems with postoperative headache, which was a common complication after retrosigmoid vestibular neurectomy, Silverstein and colleagues14–16 subsequently proposed a combined retrosigmoid-retrolabyrinthine approach.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

Patients are often desperate for relief of debilitating symptoms, and are anxious to try any treatment that offers a chance at cure. Patients should be counseled that there is no promise of a cure with any treatment, and that often the best course is a conservative one. This is especially true for patients with vertigo that is not due to Meniere’s disease because surgery for these patients is much less likely to succeed.1

PERTINENT NEUROANATOMY

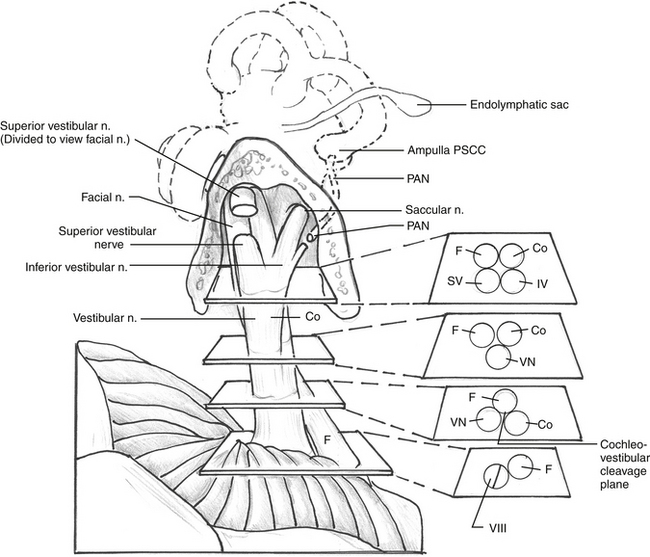

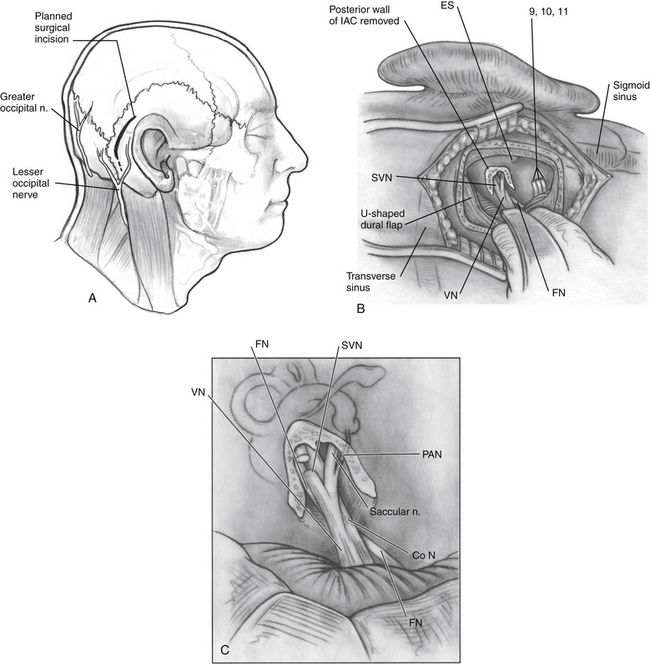

Within the IAC lie the superior and inferior vestibular nerves, the cochlear nerve, the facial nerve, the singular (posterior ampullary) nerve, and the nervus intermedius. The anatomy of these nerves and their relationships with each other are described in this section for the right ear as if the patient is supine with the head turned away from the surgeon (Fig. 36-1).

The cochlear nerve, which was initially directly anterior to the inferior vestibular nerve in the fundus of the internal canal, rotates 90 degrees inferiorly so that it is directly inferior to the superior and inferior vestibular nerves at the level of the porus acusticus. The superior and inferior vestibular nerve fibers begin to merge just medial to the transverse crest. A gross separation of the cochlear and vestibular nerve fibers usually exists medial to the porus acusticus17; however, in 25% of cases, the separation is evident only histologically. Even in cases of a visible cleavage plane, there can be a high degree of nerve fiber overlap (Fig. 36-2).18 The cochlear nerve fibers enter the brainstem slightly inferior and posterior to the vestibular nerve fibers.

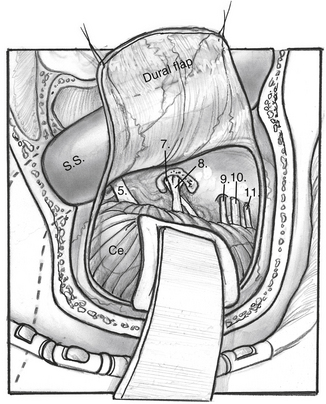

CN V is located superior to the facial and cochleovestibular nerves and can often be identified by its characteristic striations that are perpendicular to its course. CN IX, X, and XI are located inferior to the facial and cochleovestibular nerves (Fig. 36-3).

RETROLABYRINTHINE APPROACH

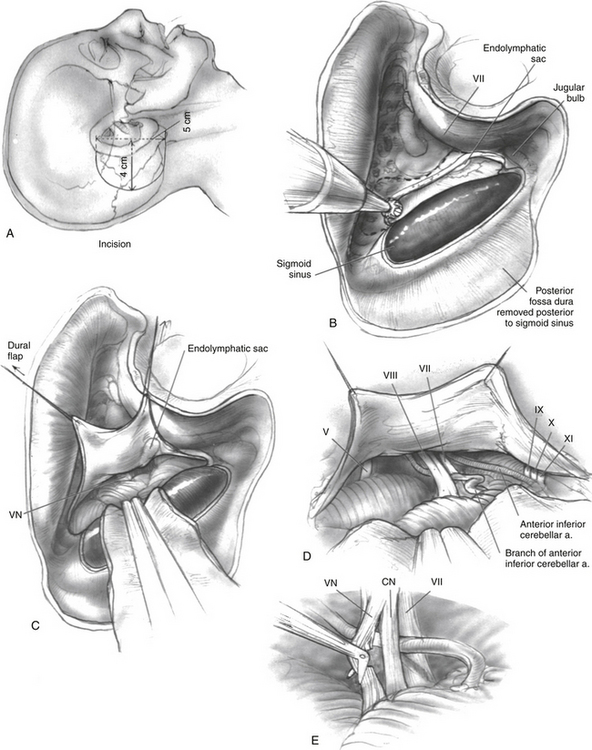

The patient is positioned in the standard fashion for mastoidectomy after removing approximately 3 to 5 cm of hair. The planned surgical site is marked and injected with a mixture of local anesthetic and epinephrine, and the scalp is prepared and draped in the standard fashion (Fig. 36-4A). The facial nerve is monitored electromyographically throughout the procedure. Auditory function is generally monitored by recording intraoperative auditory brainstem responses, although near-field CN VIII electrodes are preferred by some surgeons after the nerve is exposed. A wide postauricular scalp flap is elevated and turned forward, exposing the temporal bone. The authors prefer distinct scalp and musculoperiosteal incisions, each of which can be individually closed at the end of the case.

During the initial drilling, a fragment of bone is acquired for later use in wound closure. A large temporalis fascia graft should be harvested and set aside to dry. A complete mastoidectomy is performed, and the sigmoid sinus is carefully outlined and skeletonized (Fig. 36-4B). Posterior fossa dura is decompressed at least 1.5 cm behind the sigmoid sinus. Some surgeons leave an island of bone over the sinus, whereas others prefer to remove all bone. Regardless, enough bone overlying the sigmoid sinus should be removed to allow retraction of the sinus into the posterior aspect of the surgical defect so that the CN VIII complex can be easily visualized in the cerebellopontine angle cistern. The antrum is opened, but care should be taken not to dissect too far anteriorly to protect the epitympanum and ossicle heads. All presigmoid bone and air cells are removed posterior to the posterior semicircular canal, including the perilabyrinthine air cells, retrolabyrinthine air cells, and retrofacial tract air cells, which overlie the endolymphatic sac. The superior margin of dissection is the superior petrosal sinus, and the inferior margin is the jugular bulb. When this bone is all removed, the posterior fossa dura has been exposed. All retrofacial, facial recess, and zygomatic root air cells should be obliterated with bone wax. The wound is copiously rinsed to remove bone dust.

The dura is incised parallel to the sigmoid sinus margin, and the cerebellum is lightly retracted. When some cerebrospinal fluid is evacuated, the tentorium cerebelli and the trigeminal nerve are identified superiorly. The vestibulocochlear nerve can be visualized with gentle retraction of the cerebellum, medial to the bone of the posterior semicircular canal (Fig. 36-4C). The facial nerve is identified positively by electric stimulation after gentle retraction of the CN VIII complex. If a cleavage plane is evident in CN VIII, this is developed by blunt dissection with a microscopic instrument (Fig. 36-4D). If no cleavage plane is present, the surgeon must create an arbitrary plane by sharp dissection (Fig. 36-4E). The superior portion of the nerve, containing the vestibular fibers, is divided sharply, taking care not to injure the facial nerve or the nervus intermedius. When the nerve section is complete, the cut ends of the nerve physically separate. It is unnecessary to resect a portion of the nerve. Functional integrity of the facial nerve is confirmed by proximal stimulation after the vestibular nerve section. Care is also taken to preserve the nervus intermedius fibers, which run between CN VII and VIII.

RETROSIGMOID OR SUBOCCIPITAL APPROACH

The patient is positioned in the standard fashion for mastoidectomy or in the lateral “park-bench” position, at the discretion of the surgeon. The head is rotated contralaterally with the neck slightly flexed. A lumbar drain is placed electively by some surgeons to allow for posterior fossa decompression. Electrodes for intraoperative brainstem auditory evoked response and facial nerve monitoring are placed. The planned surgical site parallel to the hairline is marked and injected with local anesthetic containing 1:100,000 epinephrine (Fig. 36-5A). Placement of the incision avoiding the greater and lesser occipital nerves can be accomplished by using a curvilinear or sigmoidal incision along the hairline. This incision should extend from the top of the auricle down to the upper neck, just posteroinferior to the mastoid tip. The surgical site is prepared and draped in the standard fashion. Some surgeons routinely employ a lumbar drain for these cases. If this drain has been placed, 60 to 90 mL of cerebrospinal fluid is drained at the time of skin incision; this decompresses the posterior fossa and minimizes the need for cerebellar retraction.19 The skull is exposed, and a 2 cm diameter retrosigmoid craniectomy is made. Any posterior mastoid air cells entered in this process must be obliterated.

All drilling is completed before opening the dura to minimize entry of bone dust into the subarachnoid space. Emissary veins are a potential source of bleeding that can be controlled with cautery or bone wax. The dural incision may be either curvilinear or trifurcate. After opening the dura to expose the posterior fossa, the cerebellopontine angle is approached by gentle retraction of the cerebellum, preferably from the lower portion of the wound (Fig. 36-5B). Medial traction of CN VIII is dangerous to the hearing and is frequently associated with cerebellar retraction. Auditory brainstem responses should be monitored closely during this portion of the procedure. This is particularly true if a cerebellar retractor is used. The cerebellum is elevated superiorly, separating it from the temporal bone. The operculum and the endolymphatic sac can be helpful landmarks because the endolymphatic duct exits the temporal bone at the level of the IAC and is only a few millimeters posterior to the IAC.

The cranial nerves in this region are exposed by separating the arachnoid mater and the vessels. CN V and VII-XI can be visualized, with CN V being superior to the facial and vestibulocochlear nerve complex, and CN IX-XI exiting inferiorly (see Fig. 36-3). CN V can be identified by its characteristic striations, which are perpendicular to the long axis of the nerve. Identification of CN IX-XI is confirmed with identification of the jugulodural fold, a condensation of dura that extends across the sigmoid sinus from the posterior aspect of the temporal bone. Approximately 1 cm anterior to the fold, the cochleovestibular nerve enters the IAC. The facial nerve is located anteroinferior to the vestibulocochlear nerve medially along the brainstem, and continues to move superiorly and anterior to CN VIII until it enters its location in the anterosuperior portion of the IAC (see Fig. 36-1). Identification of the facial nerve can be confirmed with use of the facial nerve stimulator.

At the level of the porus, the cochlear and vestibular fibers are usually separated by a cleavage plane, allowing for sharp dissection of the cleavage plane and selective transection of the vestibular fibers. The vestibular nerve is slightly grayer in appearance than the cochlear nerve because of the more dense arrangement of the cochlear fibers. The nervus intermedius runs along the anterior aspect of the cleavage plane and may be identified with endoscopic assistance. There is also a small arteriole that frequently runs along the posterior cleavage plane. In cases where a definite cleavage plane cannot be identified, which occurs in approximately 25% of cases,20 the nerve may be arbitrarily divided as described previously, or drilling of the posterior portion of the IAC may be performed (see Fig. 36-5C).

If drilling of the posterior IAC is required, the drilling extends no further laterally than the singular canal, which carries the posterior ampullary nerve and enters the IAC approximately 2 mm medial to the falciform crest in the posteroinferior quadrant.21 When adequate exposure has been obtained, the superior vestibular and the singular nerves are sectioned. The inferior vestibular nerve should not be sectioned laterally because of its close relationship to CN VIII and the cochlear blood supply.

Careful irrigation is performed, and the dura is reapproximated. Because this approach is associated with a higher incidence of postoperative headache, many authors recommend performing a cranioplasty after the retrosigmoid approach to repair the craniectomy defect.22–24 An alternative technique described by Silverman and coworkers,19 using a sandwich of absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam), absorbable gelatin film (Gelfilm), and Gelfoam in the craniectomy defect, may prevent adhesion of cervical musculature to the dura. This Gelfoam-Gelfilm-Gelfoam sandwich has been shown to minimize the incidence of postoperative headache, and may decrease reactive chemical meningitis related to foreign cranioplasty materials. The muscle, fascia, and skin are closed in layers.

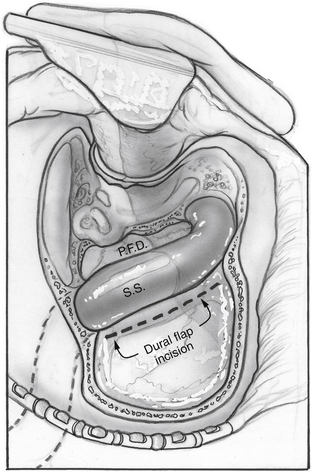

COMBINED RETROLABYRINTHINE/RETROSIGMOID APPROACH

Silverstein14 proposed a modification of the above-described techniques, termed the combined retrolabyrinthine-retrosigmoid approach. This approach involves a limited mastoidectomy with exposure of the sigmoid sinus and posterior fossa dura. A dural incision is made approximately 2 to 3 mm posterior to the sigmoid sinus, and the sinus and dura are retracted anteriorly (Fig. 36-6) to allow evaluation of the cerebellopontine angle to determine whether an identifiable cleavage plane exists between the cochlear and vestibular nerve fibers. If not, dura is reflected off the temporal bone, and the IAC is opened. The superior vestibular and posterior ampullary nerves are divided within the IAC, as in the retrosigmoid approach. This division allows performance of the neurectomy with less bone removal and less cerebellar retraction.

ENDOSCOPIC-ASSISTED VESTIBULAR NEURECTOMY

Several authors have reported on the use of endoscopic assistance for vestibular neurectomy procedures.25–27 The potential advantages include a magnified view of relevant structures, and the ability to use angled or flexible scopes to allow visualization of structures not seen well with the microscope, such as the cleavage plane between the cochlear and vestibular nerves, the nervus intermedius, the facial nerve, and branches of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery. Potential disadvantages include difficulty in visualization because of fluids on the scope, thermal injury to important structures from the heat of the endoscope, lack of instruments specifically designed for endoscopic neurotology, and difficulty because of lack of depth perception when viewing images in two dimensions.27 Any of these factors could lead to injury of structures not generally at risk when performing the procedure with binocular microscopy. The primary advantage of an endoscope may be to allow visualization of any mastoid air cells violated while drilling the IAC, so that these can be properly obliterated to prevent cerebrospinal fluid leak.

EFFICACY

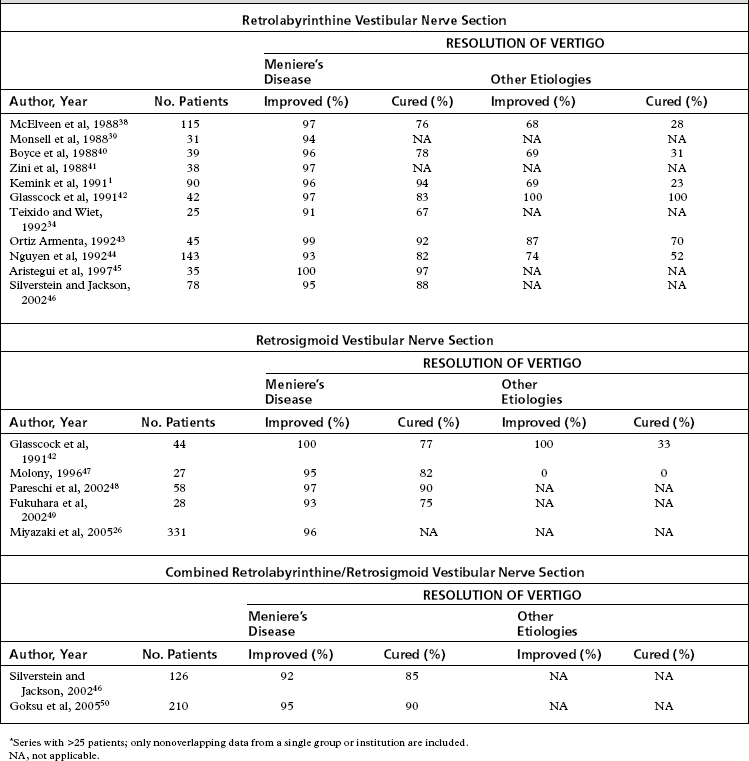

The gold standard for the surgical control of vertigo is the transmastoid labyrinthectomy. Assuming the offending ear is properly lateralized and the operation is completed successfully, the success rate for control of episodic vertigo with labyrinthectomy should be 100%. Series report success rates of greater than 95%; poor outcomes are most likely secondary to incomplete vestibular compensation.28 A review of the available literature (Table 36-1) shows that the results for the retrolabyrinthine and retrosigmoid techniques are favorable, with vertigo being improved in 91% to 100% of patients with Meniere’s disease, and 68% to 100% of patients with vertigo from etiologies not related to Meniere’s disease. The combined retrolabyrinthine and retrosigmoid approach is reported to have a success rate of 92% to 95% for patients with Meniere’s disease. No data are available for patients with other causes of vertigo. A challenge in interpretation of these data is the natural course of Meniere’s disease, which is often a progression to spontaneous complete relief of vertigo even if no treatment is provided.29–32

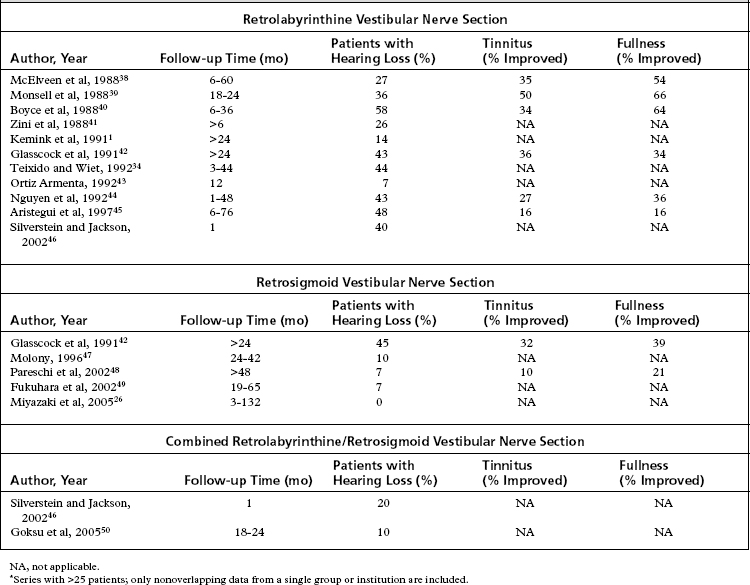

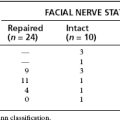

The advantage of selective vestibular neurectomy over destructive labyrinthine procedures is division of the vestibular fibers with preservation of the cochlear fibers. The ability of the procedure to preserve hearing is an important consideration. As mentioned earlier, vestibular neurectomy does not change the course of the hearing loss, but is designed only to treat the immediately debilitating symptom of vertigo. In addition, vestibular neurectomy itself introduces a risk of hearing loss secondary to the surgery. Lack of a distinct cleavage plane between the vestibular and cochlear nerve fibers is the primary cause of damage to auditory fibers. This risk may be theoretically decreased using the retrosigmoid approach, owing to surgical division of the vestibular nerve more laterally, where the cleavage plane becomes more distinct. Medial retraction of the auditory nerve may also lead to a sensorineural hearing loss. In addition, a conductive hearing loss may occur later from fixation of the ossicular chain caused by bone dust that accumulates in the oval window during the procedure.33,34 A study by Teixido and Wiet34 showed that the most common audiometric abnormality after retrolabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy is low-frequency conductive hearing loss thought to be due to ossicular fixation from this mechanism.

As shown in Table 36-2, reports of hearing loss after vestibular neurectomy state that retrolabyrinthine patients have a 7% to 58% incidence of hearing loss, whereas retrosigmoid patients have a 7% to 45% incidence of hearing loss. These data must be interpreted with caution because the postoperative time points at which the hearing losses were evaluated vary among studies, and are no doubt contaminated by the continued decline of hearing because of the natural progression of Meniere’s disease. A study by Wazen and coworkers35 showed that serviceable hearing decreased from 81% to 43% of patients at an average of 4 years after vestibular neurectomy. A reasonable conclusion may be drawn that hearing loss continues after vestibular neurectomy, just as it does with untreated Meniere’s disease,29–31 but perhaps at a slightly slower rate.

The other classic symptoms of Meniere’s disease, tinnitus and aural fullness, also occasionally improve after vestibular neurectomy. As shown in Table 36-2, tinnitus was reduced in half of patients, and aural fullness was reduced in two thirds of patients after the retrolabyrinthine approach.

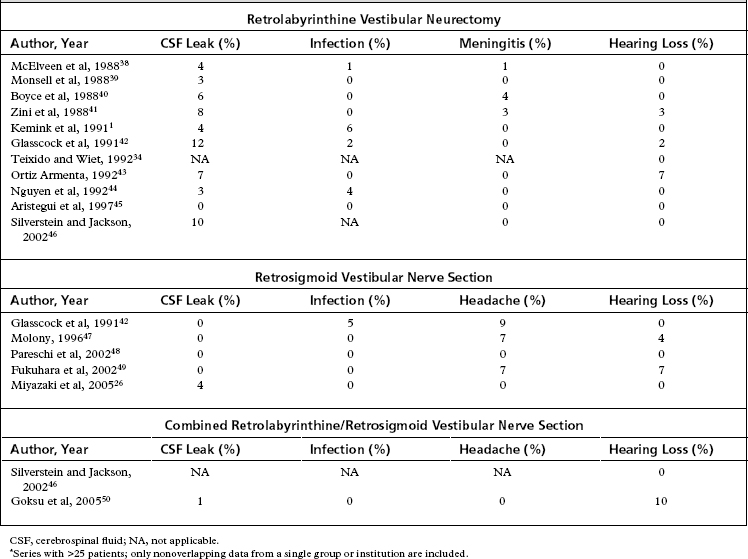

COMPLICATIONS

Table 36-3 summarizes the complications encountered with posterior fossa vestibular neurectomy. For the retrolabyrinthine approach, the most common complication is cerebrospinal fluid leak, which occurs in up to 12% of patients. Wound infection and meningitis are also common complications, occurring in up to 6% and 4% of patients. The most commonly cited complication with retrosigmoid vestibular neurectomy is significant postoperative headache, sometimes disabling, which can persist for years after surgery. The reported incidence of cerebrospinal leak and wound infection are much lower than for the retrolabyrinthine approach at 4%, and the wound infection rate is similar at 5%. Although facial nerve paresis is a risk, this occurs rarely with the posterior fossa approaches and is not generally reported in the literature. Other complications reported in the literature for these operations include hydrocephalus, continued imbalance, tinnitus, aseptic meningitis, and abdominal hematoma if an abdominal fat graft is used.

Efforts to prevent the attachment of the deep neck musculature to exposed dura, designing skin incisions to avoid the occipital nerves, and the avoidance or minimization of intradural bone drilling all have been shown to decrease the incidence of postoperative headache.19 The prevention of cervical muscle adherence to dura has been described using cranioplasty and wound closure modifications. Cranioplasty to replace missing bone volume was initially advocated to decrease the incidence of postoperative headache. Cranioplasty increases operative time, however, and more recent studies have shown that the foreign materials such as methylmethacrylate may lead to a higher incidence of headache, owing to increased local tissue reaction.36 In addition, the data suggest that there is no decrease in the frequency of postoperative headache in cranioplasty patients.36,37

1. Kemink J.L., Telian S.A., el-Kashlan H., et al. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section: efficacy in disorders other than Meniere’s disease. Laryngoscope. 1991;101(5):523-528.

2. Jackler R.K., Whinney D. A century of eighth nerve surgery. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22(3):401-416.

3. Frazier C. Intracranial division of the auditory nerve for persistent aural vertigo. Surgery Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1912;15:524-529.

4. McKenzie K. Intracranial division of the vestibular portion of the auditory nerve for Meniere’s disease. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1936;34:1127-1152.

5. Green R.E., Douglass C.C. Intracranial division of the eighth nerve for Meniere’s disease; a follow-up study of patients operated on by Dr. Walter E. Dandy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1951;60(3):610-621.

6. House W.F. Surgical exposure of the internal auditory canal and its contents through the middle, cranial fossa. Laryngoscope. 1961;71:1363-1385.

7. Fisch U. Vestibular and cochlear neurectomy. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1974;78(4):ORL252-ORL255.

8. Glasscock M.E.3rd. Vestibular nerve section. Middle fossa and translabyrinthine. Arch Otolaryngol. 1973;97(2):112-114.

9. Hitselberger W.E., Pulec J.L. Trigeminal nerve (posterior root) retrolabyrinthine selective section. Operative procedure for intractable pain. Arch Otolaryngol. 1972;96(5):412-415.

10. Badke M.B., Pyle G.M., Shea T., et al. Outcomes in vestibular ablative procedures. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23(4):504-509.

11. Silverstein H., Norrell H. Retrolabyrinthine surgery: a direct approach to the cerebellopontine angle. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1980;88(4):462-469.

12. Silverstein H., Norrell H. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1982;90(6):778-782.

13. Silverstein H., McDaniel A., Wazen J., et al. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy with simultaneous monitoring of eighth nerve and brain stem auditory evoked potentials. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93(6):736-742.

14. Silverstein H., Nichols M.L., Rosenberg S., et al. Combined retrolabyrinthine-retrosigmoid approach for improved exposure of the posterior fossa without cerebellar retraction. Skull Base Surg. 1995;5(3):177-180.

15. Silverstein H., Norrell H., Smouha E., et al. Combined retrolab-retrosigmoid vestibular neurectomy. An evolution in approach. Am J Otol. 1989;10(3):166-169.

16. Silverstein H., Norrell H., Smouha E., et al. An evolution of approach in vestibular neurectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;102(4):374-381.

17. Silverstein H. Cochlear and vestibular gross and histologic anatomy (as seen from postauricular approach). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92(2):207-211.

18. Rasmussen A. Studies of the VIIIth cranial nerve of man. Laryngoscope. 1940;50:667.

19. Silverman D.A., Hughes G.B., Kinney S.E., et al. Technical modifications of suboccipital craniectomy for prevention of postoperative headache. Skull Base. 2004;14(2):77-84.

20. Megerian C.A., Hanekamp J.S., Cosenza M.J., et al. Selective retrosigmoid vestibular neurectomy without internal auditory canal drill-out: an anatomic study. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23(2):218-223.

21. Kartush J.M., Telian S.A., Graham M.D., et al. Anatomic basis for labyrinthine preservation during posterior fossa acoustic tumor surgery. Laryngoscope. 1986;96(9 Pt 1):1024-1028.

22. Wazen J.J., Sisti M., Lam S.M. Cranioplasty in acoustic neuroma surgery. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(8):1294-1297.

23. Feghali J.G., Elowitz E.H. Split calvarial graft cranioplasty for the prevention of headache after retrosigmoid resection of acoustic neuromas. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(10):1450-1452.

24. Soumekh B., Levine S.C., Haines S.J., et al. Retrospective study of postcraniotomy headaches in suboccipital approach: diagnosis and management. Am J Otol. 1996;17(4):617-619.

25. Ozluoglu L.N., Akbasak A. Video endoscopy-assisted vestibular neurectomy: a new approach to the eighth cranial nerve. Skull Base Surg. 1996;6(4):215-219.

26. Miyazaki H., Deveze A., Magnan J. Neuro-otologic surgery through minimally invasive retrosigmoid approach: endoscope assisted microvascular decompression, vestibular neurotomy, and tumor removal. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(9):1612-1617.

27. Wackym P.A., King W.A., Barker F.G., et al. Endoscope-assisted vestibular neurectomy. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(12):1787-1793.

28. Eisenman D.J., Speers R., Telian S.A. Labyrinthectomy versus vestibular neurectomy: long-term physiologic and clinical outcomes. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22(4):539-548.

29. Quaranta A., Marini F., Sallustio V. Long-term outcome of Meniere’s disease: endolymphatic mastoid shunt versus natural history. Audiol Neurootol. 1998;3(1):54-60.

30. Quaranta A., Onofri M., Sallustio V., et al. Comparison of long-term hearing results after vestibular neurectomy, endolymphatic mastoid shunt, and medical therapy. Am J Otol. 1997;18(4):444-448.

31. Silverstein H., Smouha E., Jones R. Natural history vs. surgery for Meniere’s disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;100(1):6-16.

32. Filipo R., Barbara M. Natural course of Meniere’s disease in surgically-selected patients. Ear Nose Throat J. 1994;73(4):254-257.

33. Parikh A.A., Brookes G.B. Conductive hearing loss following retrolabyrinthine surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122(8):841-843.

34. Teixido M., Wiet R.J. Hearing results in retrolabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy. Laryngoscope. 1992;102(1):33-38.

35. Wazen J.J., Spitzer J., Kasper C., et al. Long-term hearing results following vestibular surgery in Meniere’s disease. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(10):1470-1473.

36. Lovely T.J., Lowry D.W., Jannetta P.J. Functional outcome and the effect of cranioplasty after retromastoid craniectomy for microvascular decompression. Surg Neurol. 1999;51(2):191-197.

37. Catalano P.J., Jacobowitz O., Post K.D. Prevention of headache after retrosigmoid removal of acoustic tumors. Am J Otol. 1996;17(6):904-908.

38. McElveen J.T.Jr., Shelton C., Hitselberger W.E., et al. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy: a reevaluation. Laryngoscope. 1988;98(5):502-506.

39. Monsell E.M., Wiet R.J., Young N.M., et al. Surgical treatment of vertigo with retrolabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy. Laryngoscope. 1988;98(8 Pt 1):835-839.

40. Boyce S.E., Mischke R.E., Goin D.W. Hearing results and control of vertigo after retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section. Laryngoscope. 1988;98(3):257-261.

41. Zini C., Mazzoni A., Gandolfi A., et al. Retrolabyrinthine versus middle fossa vestibular neurectomy. Am J Otol. 1988;9(6):448-450.

42. Glasscock M.E.3rd, Thedinger B.A., Cueva R.A., et al. An analysis of the retrolabyrinthine vs. the retrosigmoid vestibular nerve section. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;104(1):88-95.

43. Ortiz Armenta A. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy. 10 years’ experience. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord). 1992;113(5):413-417.

44. Nguyen C.D., Brackmann D.E., Crane R.T., et al. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section: evaluation of technical modification in 143 cases. Am J Otol. 1992;13(4):328-332.

45. Aristegui M., Canalis R.F., Naguib M., et al. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section: a current appraisal. Ear Nose Throat J. 1997;76(8):578-583.

46. Silverstein H., Jackson L.E. Vestibular nerve section. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2002;35(3):655-673.

47. Molony T.B. Decision making in vestibular neurectomy. Am J Otol. 1996;17(3):421-424.

48. Pareschi R., Destito D., Falco Raucci A., et al. Posterior fossa vestibular neurotomy as primary surgical treatment of Meniere’s disease: a re-evaluation. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116(8):593-596.

49. Fukuhara T., Silverman D.A., Hughes G.B., et al. Vestibular nerve sectioning for intractable vertigo: efficacy of simplified retrosigmoid approach. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23(1):67-72.

50. Goksu N., Yilmaz M., Bayramoglu I., et al. Combined retrosigmoid retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section: results of our experience over 10 years. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26(3):481-483.