Chapter 123 Retrogasserian Glycerol Rhizolysis in Trigeminal Neuralgia

History

The discovery of the beneficial effects of glycerol in patients with TN was purely accidental. During the course of development of a procedure for producing lesions in the gasserian ganglion in patients with TN in the 1970s, in which the Leksell gamma knife in Stockholm was to be used, x-ray contrast medium (metrizamide) and glycerol were tried as vehicles for a radiopaque metal dust (tantalum powder). The tantalum powder was to be introduced into the retroganglionic cistern as a permanent marker to constitute a visible target for the subsequent stereotactic calculations.1,2 Glycerol was chosen as the vehicle because, being the base for triglyceride formation in the body, it was presumed to be harmless, and its viscosity would ensure that the tantalum suspension was maintained long enough for the powder to be deposited in the trigeminal cistern. In fact, glycerol had been used earlier in the treatment of TN as a vehicle for the highly neurolytic phenol,3 which was used for percutaneous treatment of TN at that time. It was noted that merely injecting the glycerol and tantalum dust mixture in patients abolished paroxysmal pain before the gamma knife procedure was performed. On the basis of these observations, Håkanson developed the technique for treating TN by glycerol injection into the trigeminal cistern. The first series of patients was presented in 1981,4 and the method was then rapidly adopted in many neurosurgical centers.

Over the years, many series of patients treated using Håkanson’s procedure, or some variation of the original method, have been reported. The results from different series have been highly variable. In many centers the outcome has been quite satisfactory,5–9 and glycerol rhizolysis has continued to be the method of choice, particularly for elderly and infirm patients. In other series, the results have been so discouraging (Siegfried, 1985, and Rhoton, 1985, unpublished results, both cited in Sweet10; Price, 1985, unpublished results, cited in Sweet11 and Fujimaki and colleagues12) that some neurosurgeons have entirely abandoned the procedure.

Probable Mechanisms of Action of Glycerol

In the literature we find no satisfactory animal models of trigeminal neuralgia, and it is difficult to obtain relevant histologic data from patients. However, trigeminal neuralgia presents with such idiosyncratic signs and symptoms, and responds to so distinctive a set of therapeutic modalities, that scientific deduction can be used to generate likely hypotheses. The “ignition hypothesis” of trigeminal neuralgia13–15 is based on advances in the understanding of abnormal electrical activation of injured sensory neurons,16 supported by histopathologic examinations of biopsy specimens from patients with trigeminal neuralgia who are undergoing microvascular decompression (MVD) of the trigeminal root in the posterior fossa.13 According to this hypothesis, trigeminal neuralgia results from specific abnormal activation of trigeminal afferent neurons in the trigeminal root or ganglion. Injury renders both axons and axotomized somata hyperexcitable. The hyperexcitable afferents, in turn, induce pain paroxysms as a result of synchronized after-discharge activity. The ignition hypothesis accounts for the major positive and negative signs and symptoms of trigeminal neuralgia, for its pathogenesis, and for the efficacy of treatment modalities (for discussion, see Devor et al. 14 and Rappaport and Devor15).

Morphologic Effects of Glycerol

Glycerol is a trivalent alcohol normally present in human tissue, where it forms the skeleton of the triglycerides, among other functions.17,18 Glycerol readily penetrates cell membranes and seems to possess distinct cryoprotective properties beneficial to cells. Its toxicity is low, and comparatively high doses must be injected systemically or intrathecally to induce toxic effects.19,20 Glycerol’s neurolytic action is thought to be due to its hypertonicity, a condition known to injure nerve fibers, especially thin, unmyelinated, and myelinated fibers.21 Although the myelin sheath of the coarse fibers gives some transitory protection from this effect, length of exposure, neuron type, and the presence of previous demyelination may be important determinants of the vulnerability of individual fibers. For example, with longer exposures, Robertson22 and Pal and colleagues23 observed that myelinated fibers were particularly vulnerable, and the degree of damage positively correlated with fiber diameter.

Studies on isolated animal nerve fibers show morphologic changes after exposure to glycerol. These consist of disruption of the tight junction between the Schwann cells and the axolemma, without damage to the axon proper.24 Bathing the fibers in glycerol initially causes the axons to shrink, with a return to basal volume after equilibration of the substance over the cell membranes. With transfer to iso-osmotic conditions, the fibers swell markedly before returning to their normal volume. Thus, marked structural changes are observed with glycerol administration, but the conduction properties of the treated nerve axons remain intact.24

After intraneural and perineural injection of glycerol, Håkanson25 and Rengachary and associates26 observed axolysis with marked myelin sheath swelling. The coarse myelinated fibers sustained the most severe damage, whereas the small-diameter myelinated and unmyelinated fibers are relatively well preserved.23 In contrast, Bremerich and Reisert27 found only slight histomorphologic changes after glycerol injection in the region of the foramen ovale in the rat in their long-term (180 days) comparative study of axonal damage after injection of glycerol, phenol-glycerol, and saline. A more recent study in dogs submitted to glycerol injection in a single trigeminal ganglion28 demonstrated axonolysis both in myelinated as well as in nonmyelinated fibers.

The damage following glycerol injection into a cavity with isotonic body fluid is probably considerably less severe than perineural deposition. However, Lunsford and associates9 observed extensive areas of myelin degradation and axonal swelling in cats subjected to retrogasserian glycerol injections 4 to 6 weeks earlier.

The site of glycerol effects has been specifically studied by Stajcic,29 who injected 3H-labeled glycerol into peripheral branches of the maxillary nerve and in the infraorbital canal of rats. The amount of radioactivity detected in the nerve distal to the foramen rotundum, as well as in the ipsilateral and contralateral gasserian ganglion, was less than 0.1% in all specimens. The author concluded that a retrograde transport mechanism behind the effect is improbable and that the beneficial effect of glycerol occurs at the site of injection.

There is as yet no publication of an autopsy series of patients with TN treated by retrogasserian glycerol rhizolysis. Sweet11 provides an anecdotal description of a patient undergoing a retrogasserian glycerol injection of the extreme volume of 1.5 ml, with subsequent development of anesthesia dolorosa. At a posterior fossa craniotomy “many months” later, the trigeminal rootlets were found to be markedly atrophic.

Neurophysiologic Changes after Glycerol Application

Burchiel and Russel30 studied the effect of glycerol on normal and damaged nerves in a rat neuroma model. The neuromas, produced by sectioning of the saphenous nerve, were mechanosensitive and discharged both spontaneously and in response to light manipulation. These researchers found evidence supporting the view that glycerol exerts its major action on the large-diameter fibers. Exposure of the injured nerve to glycerol induced a short episode of increased spontaneous firing in the nerve, a response shown to originate from the myelinated fibers.

The observation by Rappaport and associates31 that glycerol injected into neuromas was more effective than alcohol in decreasing autotomy in rats suggests that autotomy may be related to unpleasant “tic-like” paresthesias. The therapeutic mechanism, according to these investigators, could be suppression of ectopic impulse barrage from the neuroma.

Sweet and co-workers32 found that glycerol injected into the trigeminal cistern of patients abolished the late components (corresponding to A-delta and C fibers) of trigeminal root potentials recorded with electric stimulation of the surface of the cheek. These recordings were made only minutes after the injection, and therefore do not permit conclusions concerning long-term effects.

Hellstrand and colleagues (unpublished data; see Håkanson25) studied the effects of glycerol both on isolated frog nerve and on trigeminal root fibers after cisternal injection in the cat. They observed a severe reduction of the evoked potentials with glycerol but a nearly total restoration after rinsing the compartment with saline. This recoverability probably has a bearing on clinical effects and must be taken into account when interpreting the short-term observations of Sweet and associates32 referred to previously. Based on knowledge that glycerol requires at least 30 minutes to equilibrate across a membrane of a living cell and according to the aforementioned experimental observations, evacuation of the glycerol from the cistern after a short time (e.g., 5 to 20 minutes10,33,34) might induce more severe damage, especially to fine fiber systems, than a slow unloading by diffusion into the subarachnoid space.

Longer-term observations of trigeminal evoked potentials have been reported by Bennett and Lunsford,35 who investigated patients before and 6 weeks after trigeminal glycerol rhizolysis. They confirmed the earlier findings of Bennett and Jannetta36 that thresholds were elevated and evoked potentials had a markedly increased latency on the affected side compared with the healthy one. An additional, unexpected finding was that these aberrations were “normalized” after glycerol rhizolysis. Because partially demyelinated fibers are known to conduct with a slower velocity and at a lower rate,37,38 they interpreted this finding to indicate that glycerol selectively attacked partially damaged trigeminal axons and, after their elimination, the evoked trigeminal potentials appeared “normalized.”

Further long-term observations were supplied by Lunsford and colleagues,9 who noted the most marked changes in trigeminal evoked potentials in cats in the large-diameter myelinated fibers, with additional changes noted as late as 6 weeks after the injection.

Quantitative sensory testing using von Frey hairs, mechanical pulses, and the Marstock technique39 also corroborates the notion that glycerol acts mainly on the large myelinated fiber spectrum.40 Eide and Stubhaug41 examined thresholds for tactile and temperature stimuli in patients with TN before and after glycerol rhizolysis. They found evidence that pain relief after glycerol treatment involved normalization of previously abnormal temporal summation phenomena with little accompanying sensory loss. Kumar and associates42 found postinjection quantitative abnormalities of the blink reflex that correlated with sensory impairment.

Thus experimental and clinical observations indicate that the effects of glycerol may be due to its hyperosmolarity and that the rate of alteration of osmolarity is critical for the effect. Furthermore, there are indications that the major part of the effect is exerted through actions on large myelinated fibers, notably those with previous damage to the myelin sheath, thereby possibly affecting the “trigger mechanism” for pain paroxysm. Glycerol has also been reported to downregulate central neuronal hyperexcitability, often without signs of significant additional nerve damage.41

Technique

The original technique of Håkanson has been subject to many modifications by various neurosurgeons. These variations encompass the type of anesthesia selected, general or local; patient position and fluoroscopic projection; whether cisternography is performed; other modes of localization of the needle tip (electric stimulation; reactions to drop-by-drop injection of glycerol, local anesthetic injection43); the dose of glycerol used; instillation of glycerol in one step or as minute volumes in an incremental fashion, with intermittent sensory testing; trials to empty the cistern after attaining a satisfactory effect according to perioperative testing; and how long the patient is kept sitting with the head flexed after completion of the procedure.

Some of these modifications have resulted in less satisfactory results.10,12,33,44 We consider retrogasserian glycerol rhizolysis to be an anatomically based method aimed at graded lesioning of fibers in a certain locus. Thus the localization procedure should also be anatomic and the treatment should be meticulously performed, using the smallest possible volume of pure, sterile glycerol considered to be effective in each case.

Anatomic Landmarks and Important Structures

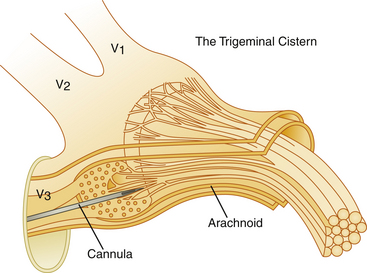

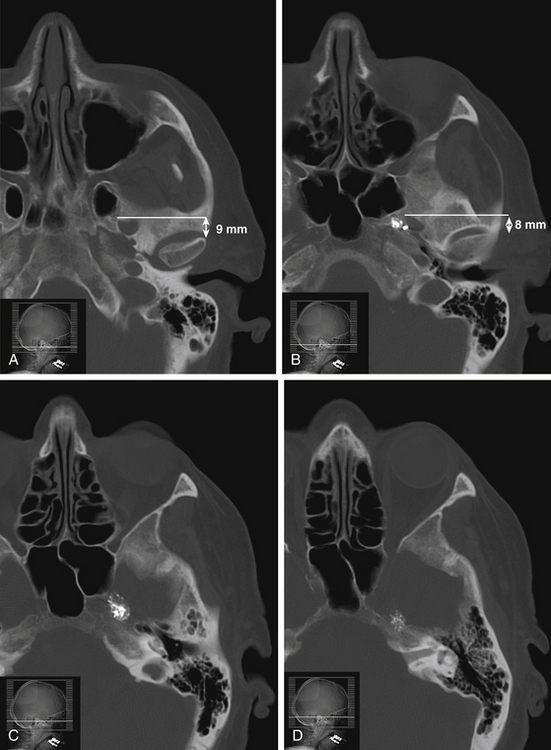

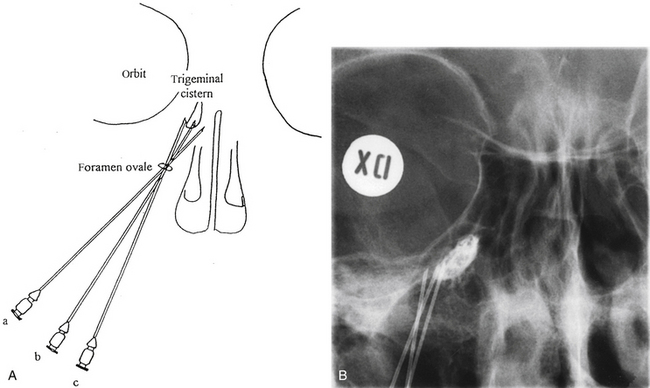

The trigeminal cistern is punctured by the anterior percutaneous route through the foramen ovale, as described by Härtel45 (Fig. 123-1). After local anesthesia, a 22-gauge lumbar cannula (outer diameter 0.7 mm; length 90 mm) is inserted from a point approximately 3 to 4 cm lateral to the corner of the mouth. The trajectory is aimed at a point that lies, in the lateral view, approximately 0.5 cm anterior to the anterior margin of the mandibular joint, and in the anteroposterior view, toward the medial margin of the pupil with the eyeball in the neutral position. There are several landmarks that may be used for reaching the foramen ovale,46,47 but in most cases these two coordinates are sufficient. In Fig. 123-2, CT scans from a patient with tantalum dust in the trigeminal cistern are provided to show the relationship of the oval foramen and the trigeminal cistern to these structures (Fig. 123-2 A through D).

When the tip of the cannula is located inside the arachnoid of the trigeminal cistern, there should be a spontaneous exit of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), especially at the first treatment. Because the location of the trigeminal ganglion and cistern can vary in relation to the landmarks of the skull base, a contrast injection must be performed to ascertain the correct site for glycerol injection. However, spontaneous CSF drainage is not sufficient for accepting the location as intracisternal, as CSF may originate from other locations; in fact a brisk flow of CSF often indicates a subtemporal tip location.

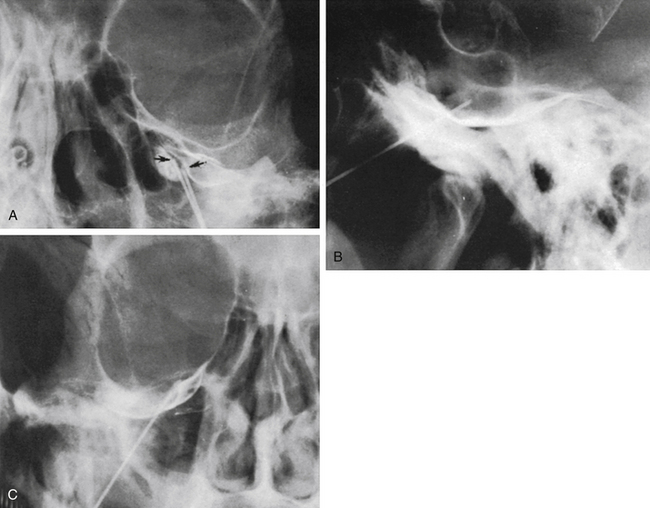

Trigeminal Cisternography

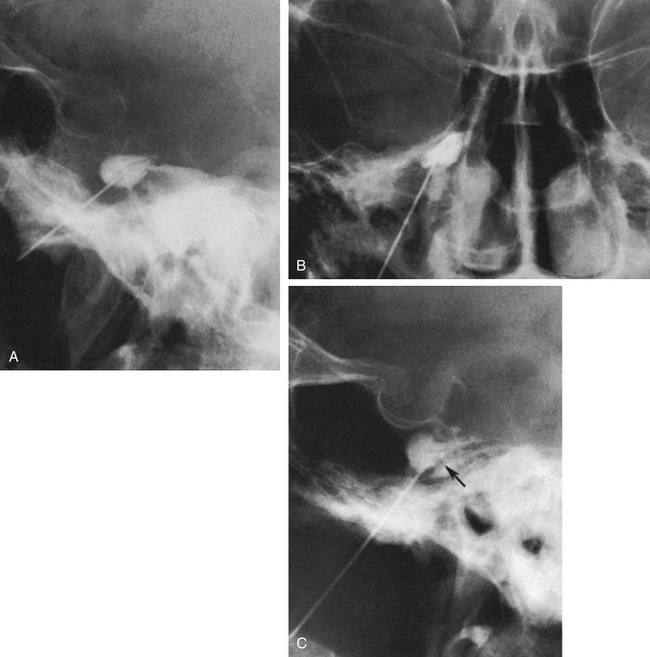

The technique we use is essentially the same as that described by Håkanson,48 although estimation of the cisternal volume is of less importance for deciding what volume of glycerol to inject. The contrast medium must be water soluble, with high radiographic attenuation and low toxicity, and must have a higher specific gravity than CSF. The contrast medium used since 1986 is iohexol (300 mg iodine/ml).49 Approximately 0.3 to 0.6 ml is injected with the patient sitting with his or her head slightly flexed to retain as much of the medium in the cistern as possible. If intermittent fluoroscopy is used during injection, the position of the needle tip may be estimated immediately, but it should always be confirmed by radiography in both the lateral and anteroposterior projections. The typical appearance of the trigeminal cistern is illustrated in Fig. 123-3. Ideally, the sensory root filaments (and sometimes the motor portion) should be visualized by lateral cisternography, leaving no doubt about the intracisternal position of the tip. The typical 45-degree medial tilt of the cistern should be seen from the anteroposterior view (Fig. 123-3B). The appearance of the cistern may vary considerably between patients, and it is essential that the surgeon be familiar with this anatomy. Furthermore, there is a subdural-extracisternal compartment in Meckel’s cave that may be injected with contrast medium (Fig. 123-4). This usually happens when contrast medium is injected without prior spontaneous CSF drainage, or if the needle is dislodged from the intracisternal position during injection.

Specific Difficulties

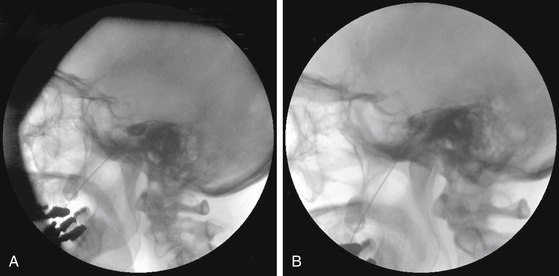

Spontaneous CSF drainage from the needle does not guarantee an intracisternal tip location. In fact, if the cannula is placed a few millimeters too lateral, the tip may be located in the subtemporal subarachnoid space, and a flow of CSF will still be produced. Subsequent cisternography solves this problem. Figure 123-5A shows the proximity of the cisternal and subtemporal subarachnoid compartments in the anteroposterior projection. Figure 123-5B and C illustrate a pure subtemporal contrast injection. Our strategy in this case is to leave the first needle in place and to introduce a second needle using the first one for guidance (Fig. 123-6A and B). It cannot be overemphasized that spontaneous CSF drainage is required before contrast injection. If, in such a case, the contrast medium is injected without fulfilling this requirement, the glycerol may be deposited in the extra-arachnoid, subdural compartment as shown above (see Fig. 123-4).

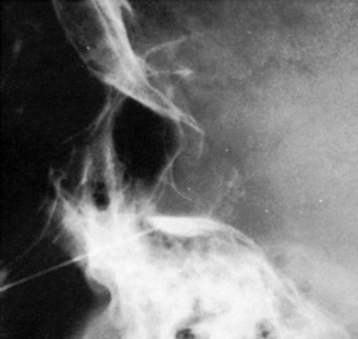

Another problem may arise if the patient’s head is not adequately tilted forward during the injection, because the contrast medium then flows out the porus trigemini and escapes to the posterior fossa, with insufficient cisternal filling to confirm the correct position of the needle tip (Fig. 123-7). This situation may also result in an underestimation of the cisternal volume.

Contrast Evacuation

When the intracisternal position of the tip has been confirmed, the syringe is gently removed from the cannula and the contrast medium permitted to flow out of it in a drop-by-drop fashion. We usually evacuate the cistern by tilting the patient to the supine position. If it is difficult to evacuate all contrast medium from the bottom of the cistern to permit the glycerol to reach the lowest root fibers (see later), the patient can be placed in the Trendelenburg position for a few minutes, a maneuver that permits the contrast medium to drain to the posterior fossa. Furthermore, the cistern may be flushed with 2 to 3 ml of sterile saline until the control radiograph indicates that the cistern is properly rinsed from contrast. Some of the less satisfactory results are probably due to failure to empty the cistern properly.12,44 An extracisternal needle-tip position precludes a subsequent glycerol injection and must lead to repositioning or abortion of the procedure.

Branch Selectivity

First, the volume of glycerol can be varied to fill more or less of the cistern. When the trigeminal cistern has been entirely emptied after contrast injection, the amount of glycerol injected partly determines which branches will be influenced. With the head of the patient only slightly flexed, a small volume of glycerol (i.e., 0.15 to 0.2 ml) is deposited at the bottom of the cistern and mainly affects the fibers of the third and second branches. Increasing the amount of glycerol causes additional rhizolysis in the two upper portions.

Finally, the position of the patient’s head during and after the injection also produces some selectivity. The patient should be sitting in the upright position during the injection. For first branch neuralgia, the head should be maximally flexed (i.e., approximately 40 degrees) and should be kept in approximately that position for 1 hour after the injection. For second branch treatment, flexion should be approximately 25 degrees, and for the third branch, the head should be slightly tilted laterally toward the affected side, but kept upright in the anteroposterior plane.5

The selectivity obtained by varying the head position has been studied by Bergenheim and colleagues,50,51 who found a highly selective effect of this maneuver with regard to the ophthalmic branch, but less selectivity for the two lower branches.

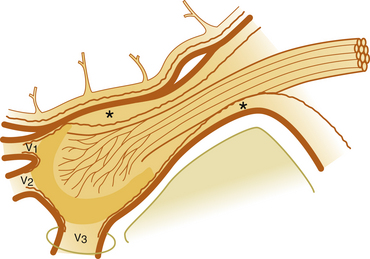

Permanent Marking of the Cistern

A permanent marking of the cistern is recommended and can easily be achieved with a mix of glycerol and sterile radiopaque tantalum dust (Merck, Haar, Germany; grain size less than 0.042 mm). Approximately 0.5 g of tantalum is mixed with 2 ml of glycerol and the suspension is then used for injection to outline the bottom of the cistern (Fig. 123-8). This is of considerable help as a guide if reinjections are needed. With certain requirements fulfilled, permanent marking may replace the need for renewed cisternography. The tantalum marking is clearly visible on radiography years after the injection. There are no indications that the metal dust causes inadvertent effects or otherwise influences the results of the treatment.

Special Considerations for Repeated Injection

Incomplete pain relief after the initial injection seems in most cases to be the result of technical problems during the procedure. Reinjections should not be performed within 3 to 4 weeks after the initial trial to allow late responders to emerge. Before reinjection, facial sensibility should be carefully examined, and if sensory impairment is found, the reinjection should be performed with a minimal amount of glycerol. Alternatively, a nondestructive procedure should be considered in these patients.

When trigeminal cisternography is performed after one or more intracisternal glycerol injections, a less satisfactory outlining of the cistern sometimes is obtained, probably due to adhesions within the cistern induced by the glycerol or contrast medium.52 The situation seems to be the same regardless of whether tantalum has been added. Figure 123-9 illustrates the appearance of a cistern before the first treatment (A) and at the repeat injection (B).

In contrast to our experience and the observations of Rappaport and Gomori52 and Lunsford53 noted no abnormalities of the cistern in patients undergoing repeated glycerol injections.

Postoperative Management

After injection, the patient should remain seated upright in bed with his head in the selected position for an hour. There is no convincing evidence that extending the time of controlled head positioning increases the therapeutic effect. However, there are indications that shortening the period of fiber exposure to glycerol by actively evacuating it from the cistern may cause more extensive and less well-controlled rhizolysis.10,50 Sweet10,34 reported that if first-branch sensory loss appears, leaving the glycerol in the cistern for 12 minutes or more may result in persistent corneal anesthesia. Hence, he recommended evacuation of the glycerol from the cistern within 10 minutes after the onset of first branch analgesia. This procedure and the amount of glycerol used are not recommended by us.

The latency for relief from neuralgia varies. Approximately half of the patients report that their paroxysms disappear immediately after the glycerol injection. In the remaining group, there may be occasional spells during the first postoperative day and sometimes for periods of up to 5 days, after which the neuralgia fades away. Even longer latencies of up to 3 weeks have been reported.53 In younger patients, the procedure may be performed on an outpatient basis. In elderly or weak patients or following general anesthesia, an overnight hospital stay is usually required.

Results

Outcomes are reviewed with respect to initial and long-term relief from the paroxysmal pain, rate of recurrence, and various complications such as sensory disturbances recorded, herpes eruptions, and postoperative meningitis of the aseptic and bacterial types. Some of the major series are examined, and relevant data are given in tables and text. There is a paucity of reports of major series after 2005, and in some of the earlier reported materials previously published smaller case series might have been included. Usually this is not clear from the description.

Evaluation of Different Series

A major problem in the evaluation of results from different series is the variation in technique. Different methods have been used by different authors to determine an intracisternal needle position before glycerol injection. Strategies vary from that recommended—use of cisternography,6,7,53,54 drop-by-drop incremental glycerol injection, and intraoperative recording of sensory response5,8,55—to the use of electric stimulation in the same way as is done in selective thermocoagulation.32,33

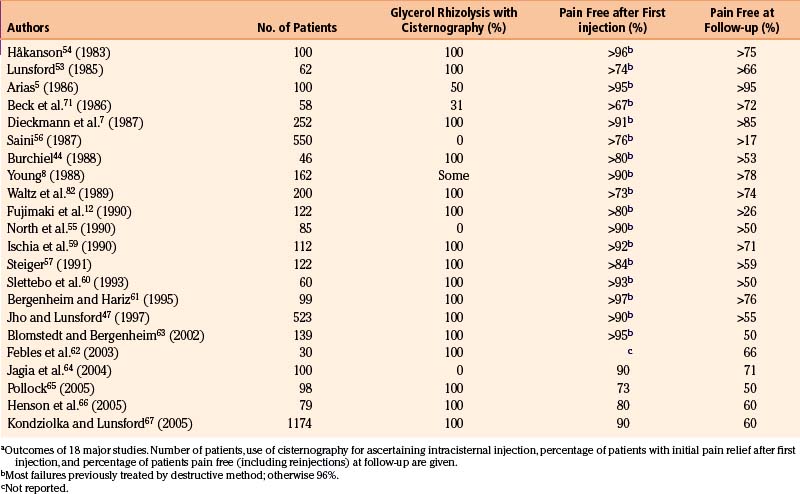

In some series, cisternography has not been used8,55,56; in others only in conjunction with treatment of first branch neuralgia; and in some only when there is no spontaneous CSF outflow through the cannula.57 The extent to which cisternography is used in the series reviewed is shown in Table 123-1. In our experience, there is a relationship among the quality of the cisternography, adequacy of needle placement, and treatment outcome.

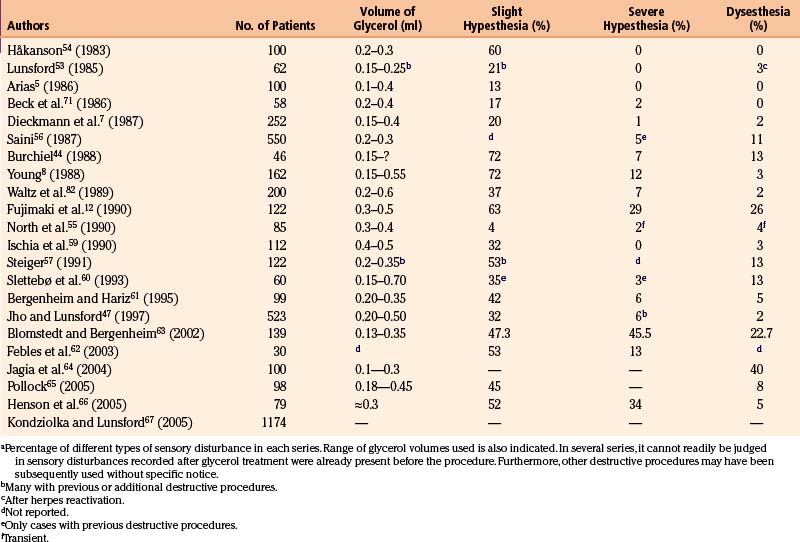

A very important factor is the amount of glycerol used. Sometimes the range of volumes is not explicit, and in several series it far exceeds the original recommendations.8,12,58,59 This has to be taken into account when interpreting the data (ranges of volumes of glycerol used are given later; see Table 123-3).

Short- and Long-Term Results

The outcomes in 22 major series with long-term follow-up periods encompassing more than 2700 patients are given in Table 123-1. Cisternography was used routinely for all patients in only 16 of the series.7,12,44,47,53,54,57–67

The follow-up periods in these series range from a few months to more than 10 years. The recurrence rates are difficult to estimate correctly because of the differences in techniques of reporting, statistics, and so forth. Kaplan-Meier analysis has been used by several researchers,44,55,57,59 facilitating the interpretation of recurrences.

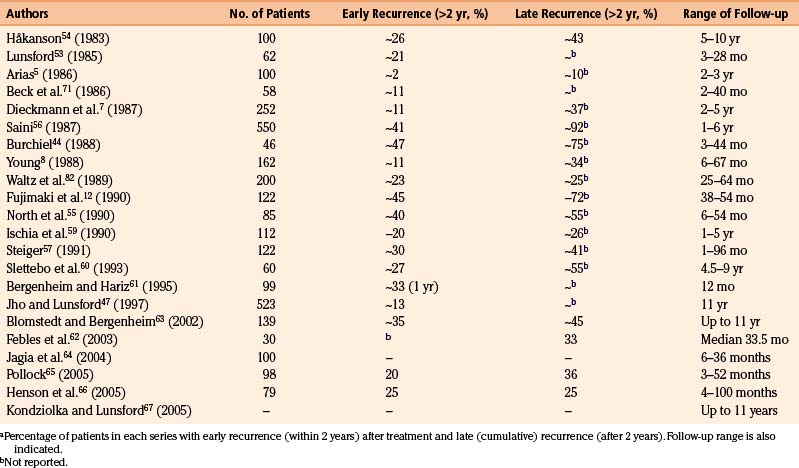

The recurrence rate in relation to length of follow-up is reviewed in Table 123-2. Within roughly 2 years of treatment, between 2% and 50% of patients with a successful initial outcome experience recurrent pain. This large variation obviously casts doubt on both the technical performance of the procedure and the follow-up methodology. It is difficult to evaluate how many of the patients have been reinjected, and if these cases are included in the final results.

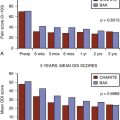

The original Stockholm series of 100 patients was followed between 5 and 10 years (mean, 5 years, 4 months). At the last follow-up, 53% were still pain free after the first injection. Twenty-two patients had at that time been reinjected with glycerol and, in total, 75% of patients from the entire series were pain free, and an additional 23% had only mild pain easily controlled by a pharmaceutical regimen.40 The average volume of glycerol injected in this series was 0.21 ml.

The average risk of recurrence within 2 years is approximately 20%, and the rate of late reappearance of symptoms (within 5 to 10 years) approaches 50%. Nevertheless, because injection can be repeated and carries little risk for the patient, most of the patients (more than 75%) may be maintained pain free by a small number of reinjections (Table 123-1). By comparison, Jannetta68 found an 80% rate of permanent pain relief in most series of microvascular decompression, 10% with some pain, and a 10% failure rate.

Two reports of major series of patients with TN treated by glycerol rhizolysis have been presented by Spaziante and colleagues69 and Lunsford and Duma.70 The two series comprise 191 and 480 patients, respectively. The follow-up periods are as long as 10 years. The percentage of patients pain free immediately after treatment was 93% in the series of Spaziante and associates69; long-term follow-up showed that 77%69 and 75%70 of patients were pain free. No patients with anesthesia dolorosa were observed, but mild hypesthesia was found in 46% and 20%, respectively. Both teams of researchers concluded that glycerol rhizolysis is a mildly neurodestructive procedure indicated as the first choice69 in elderly patients, those with MS, and in patients in whom other procedures, including microvascular decompression, have been unsuccessful.70

A 1997 report of the Pittsburgh series by Jho and Lunsford47 showed that of their large group of 523 patients, 90% were immediately pain free and 55% stayed pain free at follow-up (which extended to more than 10 years). The highest figures for patients initially pain free are those of Håkanson4 (96%) and Bergenheim and Hariz61 (97%).

Side Effects and Complications

Glycerol rhizolysis in the hands of an experienced and careful neurosurgeon should not result in serious complications. Only one fatal myocardial infarction has been reported47,70,71 in the recovery room after the procedure. Despite the fact that glycerol rhizolysis is used in patients of advanced age and sometimes with severe disabilities, the number of severe complications is remarkably low. Other serious complications relate to the attempts to penetrate the foramen ovale with a needle (e.g., intracranial hemorrhage) rather than glycerol instillation per se.11

The most feared consequence of neurolytic procedures, postoperative anesthesia dolorosa, is rarely observed after glycerol rhizolysis. An exception to this is the rather heterogeneous series of 552 cases by Saini,56 in which rhizolysis was performed without cisternography or some other technique to confirm the localization of the needle tip before glycerol injection. In this series, the number of patients with anesthesia dolorosa was 26 (5%). Furthermore, 6 patients (3%) had signs of disturbance of third-branch motor function. This malfunction resolved within 3 to 4 months after injection. Transient masseter weakness has also been described by others.58,59 Otherwise, only single cases with transitory cranial nerve dysfunction after glycerol rhizolysis have been reported. Some of these are reviewed by Sweet.11

A review of 260 consecutive procedures performed in 139 patients between 1986 and 1987 reported a fairly high frequency of perioperative side effects.63 In this series, a variety of intraoperative technical obstacles, severe vasovagal responses, and even cardiac arrest occurred. In total, complications or side effects occurred in 67.3% of procedures. This series evidently encompasses learning curves for several surgeons. Penetration of the foramina of Versalius (0.8%) and spinosum (0.4%) occurred, as did buccal penetration (1.5%). Actually, three patients (1.2%) reported a postoperative ipsilateral decrease of hearing ability. Arterial bleeding occurred in 0.4%, while venous blood from the needle occurred in 3.5%. The side effects and complications are detailed in Tables 123-3 and 123-4.

Hypesthesia

Serious sensory disturbance (e.g., anesthesia dolorosa) is rare after glycerol rhizolysis. However, transitory facial hypesthesia is a common phenomenon (up to 70%) after the procedure. The complaints usually vanish 3 to 6 months after the operation.5,8,40,58

The frequency of slight hypesthesia persisting for longer periods is variable between different series (see Table 123-3). In some series, only a small percentage of patients experience this,5,55 but in others more than two thirds present with hypesthesia at follow-up.8,44

More severe hypesthesia and anesthesia is rare (see Table 123-3). There is only one series with a figure approaching 30%.12 This is of course unacceptable, and the clinicians consequently abandoned the procedure. The figures from the series of Saini,56 Burchiel,44 Young,8 Waltz and associates,58 Bergenheim and Hariz,61 and Jho and Lunsford47 must also be considered high (5% to 12%). There are at least four possible explanations for this outcome: (1) some of these patients may have had other previous or subsequent destructive procedures; (2) there may have been technical difficulties during the procedure; (3) the volume of glycerol injected may have been too large; and (4) previous procedures may have produced cistern obliteration by fibrosis.47,52,53 Sweet11 described a case in which 1.5 ml of glycerol was injected in 0.1-ml increments, resulting in anesthesia dolorosa. When properly performed with a reasonable volume of glycerol, the incidence of severe sensory disturbances with glycerol rhizolysis should be low (<1%).7,40,53,54,70

Dysesthesia

Dysesthesia (and/or allodynia), spontaneous or touch-evoked unpleasant sensations, should occur rarely and mostly transiently after glycerol rhizolysis. The incidence is between 0 and 4% (see Table 123-3). However, Fujimaki and associates,12 Burchiel,44 Steiger,57 Saini,56 and Slettebø and colleagues60 report dysesthesia with frequencies between 11% and 26%. One major cause of this side effect is a previous neurodestructive procedure with a sensory disturbance not specifically recorded before the glycerol rhizolysis. Some patients may also have had procedure-induced herpes eruptions resulting in this condition,53 although this has not been observed by us. Whatever the reason, these figures are high, and dysesthesias should not be present in more than 2% of previously untreated patients with TN treated by glycerol rhizolysis.5,7,47,53,54,58,71

Infectious Side Effects

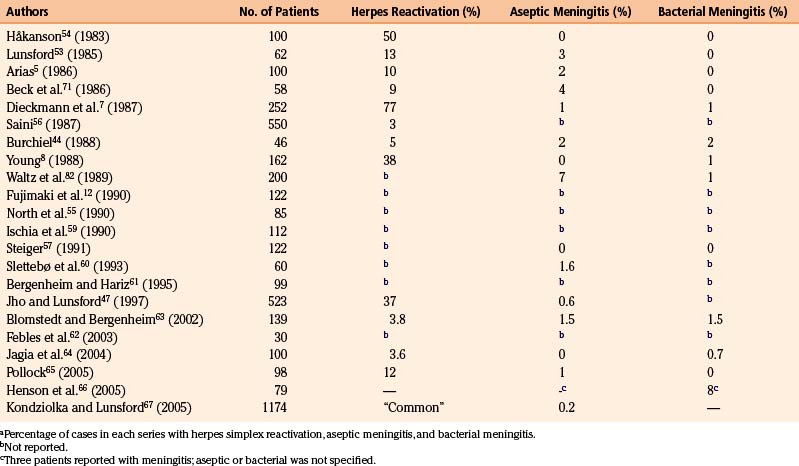

Serious infectious complications after retrogasserian glycerol rhizolysis are rare. However, reactivation of latent viral infections of neural tissue (notably herpes simplex type 1) seems more common than expected (see Table 123-4).

Herpes Activation

The activation of latent herpes simplex infections is a phenomenon encountered intermittently in neurologic surgery.72 Table 123-4 indicates the incidence of herpes simplex activation after glycerol injection. The incidence varied among different series from 3% to 77% for postoperative viral infections and this probably also largely reflects variations in accuracy of follow-up. Perioral and gingival ulcers presenting during the first week after treatment are common, but more serious outbreaks are rare. The mouth ulcers usually require no specific therapy.

Aseptic Meningitis

High fever, nuchal rigidity, and CSF pleocytosis presenting 24 to 36 hours after the procedure may indicate a meningeal reaction to an agent introduced into the trigeminal cistern. CSF cultures are usually negative. Patients presenting with these symptoms should be treated with high-dose intravenous antibiotics. When negative CSF cultures are reported, the antibiotics are discontinued. These patients usually recover completely within a few days without any sequelae. Steroids may shorten the condition’s course.53 Patients who experienced this adverse reaction after a previous treatment have undergone repeat injections with intravenous corticosteroid prophylaxis without any problems.

Aseptic meningitis has appeared with a frequency between 0% and 7% (see Table 123-4). The etiology of this reaction is obscure, although contrast agents, glycerol, tantalum dust,53 and the extent of manipulation or number of ganglion penetrations are suspects. Some investigators report diminished frequency of reactions after reducing the amount of contrast medium.58 In the Stockholm series, the frequency was 2% during the metrizamide era. Since this contrast medium was exchanged for iohexol in January 1986, we have had very few cases of aseptic meningitis. The plausibility of contrast medium as the causative agent is also supported by Arias,5 who presented a series of 100 patients of whom approximately 50% were treated without preliminary contrast medium injection. In the group subjected to contrast injection, two patients presented with aseptic meningitis, whereas no case was found in the other group. However, aseptic meningeal reactions are observed after other manipulations of the trigeminal root as well.68

Bacterial Meningitis

Bacterial meningitis after percutaneous puncture of Meckel’s cave is rare.40,73 The most common bacterial agents are those colonizing the upper respiratory tract.74 The most likely cause is inadvertent (and often unrecognized) penetration of the oral cavity mucosa. The frequency of bacterial meningitis after glycerol rhizolysis varies between 0% and 2% (see Table 123-4). The frequency in the Stockholm series remains at maximally 0.5% and seems related to the extent of manipulation during the procedure. All patients have recovered without serious sequelae after antibiotic treatment.

Special Considerations in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis

The paroxysmal facial pain in patients with MS may be clinically identical to that of classic TN. Therefore, all methods used for symptomatic treatment of TN, except microvascular decompression, may also be used in MS. TN is present in approximately 1% to 2% of patients with an established diagnosis of MS.75–77 In different series of TN, the prevalence of MS seems to range from 2% to 4%, but incidences of up to 8% have been reported.78,79 Furthermore, the occurrence of bilateral facial pain is not uncommon in MS (see Fig. 123-8), but is extremely rare in idiopathic TN.

The initial success rate is approximately equal for idiopathic TN and for TN in MS, whichever therapeutic method is used,79 but the late results differ considerably between the two. The recurrence rate of TN is much higher in association with MS. Dieckmann and colleagues7 and Linderoth and Håkanson79 reported a recurrence rate of more than 40% at a 2-year follow-up; the recurrence rate in classic TN was approximately 11% during the same period in Dieckmann and colleagues’ series. After longer follow-up periods (8 to 79 months after injection), Linderoth and Håkanson79 reported over 60% recurrent tics in the MS group, whereas the recurrence rate for the entire TN group (approximately 300 patients) was 38%.

Elevated recurrence rates after treatment of TN in MS have also been observed with selective thermocoagulation. Broggi and Franzini80 reported a 40% recurrence rate among patients with MS after thermorhizotomy compared with 9% in a series of patients without MS. This finding could not be corroborated by Brisman,81 who found no significant difference in recurrence rates between 16 MS cases and 219 non-MS cases.

The low tolerance of patients with MS to pharmacologic agents, both in form of carbamazepine and as anesthesia and sedation, merits specific comment. Linderoth and Håkanson79 reported that more than 90% of their patients with MS and TN complained of adverse medication effects. The side effects of carbamazepine in the MS group were often an aggravation of pre-existing MS symptoms. Thirty-eight percent of the patients with MS had to discontinue carbamazepine because of such symptoms. After glycerol treatment, 82% of the patients previously on carbamazepine were able to terminate it.

Glycerol Rhizolysis in the Treatment of Other Types of Facial Pain

In painful trigeminal neuropathy (previously called atypical facial pain), a paroxysmal component may exist in addition to the continuous neuropathic pain. The etiology varies (e.g., trauma, infection, postoperative, tumor, idiopathic), but includes previous treatment for TN. We agree with Dieckmann and colleagues,6 Waltz and associates,82 Lunsford and Apfelbaum,83 Rappaport,84 and Rappaport and Gomori52 that glycerol rhizolysis is contraindicated in most such cases and may aggravate a preexisting neuropathy. The sole exception is when the paroxysmal component completely dominates the clinical picture, diminishing the quality of life for the patient, and where the sensory disturbance is minimal. In such a case, a small amount of glycerol could be injected (0.15 ml). If complete pain relief is obtained (duration at least 3 months), a second injection may be performed using a somewhat larger glycerol volume.

Severe, intractable cluster headache (migraneous neuralgia, Horton’s syndrome) has also been treated by ipsilateral glycerol injection into the trigeminal cistern55,82,85 (G. Sundbärj, personal communication, 1988). The outcome has been partial, and transitory relief from symptoms has been achieved only in some of the patients, comparable with that obtained by other manipulations of the trigeminal system.86 However, one long-term follow-up study of 18 patients, followed during an average 5.2 years, demonstrated that 83% of the patients obtained immediate relief, the frequency of attacks decreased markedly, and the condition recurred in only 39% during the study period.85 Thus, glycerol therapy in cluster headache may offer some relief in chronic cases of moderate severity, but in patients with extreme pain, periorbital edema, and so on, glycerol treatment injection does not provide adequate symptom alleviation. Instead, chronic hypothalamic deep brain stimulation and occipital nerve stimulation have proven effective in selected cases.87,88

Glycerol rhizotomy has furthermore been reported to provide relief from the paroxysmal pain component in selected cases of SUNCT (short-lasting, unilateral, neuralgiform hemicrania with conjunctival injection and tearing),89 although negative outcomes of surgical therapies in this condition also have been published.90

Retrogasserian Glycerol Rhizolysis Versus Other Operative Treatments for Trigeminal Neuralgia

Glycerol rhizolysis is an inexpensive, seemingly simple procedure that must be meticulously performed by an experienced surgeon to obtain satisfactory results. The major indication remains typical idiopathic TN, particularly in the elderly, weak, or infirm. If a young patient chooses to undergo glycerol rhizolysis instead of a microvascular decompression, it should be permitted. However, if this patient has a relatively rapid recurrence, she or he should be urged to accept the open procedure instead.

In most cases, it should be possible to affect all the trigeminal branches with some selectivity; the most problematic might be the mandibular branch, especially at repeat procedures. With careful technique it should be possible to perform rhizolysis in that branch as well. In some patients subjected to several reinjections, adhesions inside the cistern may impede the glycerol from reaching the lowermost fibers. In such cases, selective thermocoagulation—or trigeminal nerve compression with a balloon—may be considered. In a recent review comparing series of glycerol rhizotomy with balloon compression, the glycerol method was recommended as the best initial percutaneous treatment for several reasons.91 In our experience glycerol rhizotomy, especially at the first or second intervention is an effective therapy, lenient for the patient, but the procedure requires attention to many details and proper cistern filling to produce the desired benefits.

Arias M.J. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia: a prospective study of 100 cases. J Neurosurg. 1986;65:32-36.

Bergenheim A.T., Hariz M.I., Laitinen L.V. Selectivity of retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1991;56:159-165.

Bergenheim A.T., Hariz M.I. Influence of previous treatment on outcome after glycerol rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:303-310.

Blomstedt P.C., Bergenheim A.T. Technical difficulties and perioperative complications of retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurgery. 2002;79:168-181.

Devor M., Amir R., Rappaport Z.H. Pathophysiology of trigeminal neuralgia: the ignition hypothesis. Clin J Pain. 2002;18(1):4-13.

Devor M., Govrin-Lippmann R., Rappaport Z.H. Mechanism of trigeminal neuralgia: an ultrastructural analysis of trigeminal root specimens obtained during microvascular decompression surgery. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(3):532-543.

Eide P.K., Stubhaug A. Sensory perception in patients with trigeminal neuralgia: effects of percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1997;68:207-211.

Ekbom K., Lindgren L., Nilsson B.Y., et al. Retro-gasserian glycerol injection in the treatment of chronic cluster headache. Cephalalgia. 1987;7:21-27.

Håkanson S. Trigeminal Neuralgia Treated by Retrogasserian Injection of Glycerol. Published dissertation. Stockholm: Karolinska Institute; 1982.

Håkanson S. Trigeminal neuralgia treated by the injection of glycerol into the trigeminal cistern. Neurosurgery. 1981;9:638-646.

Hannerz J., Linderoth B. Neurosurgical treatment of short-lasting, unilateral, neuralgiform hemicrania with conjunctival injection and tearing. Br J Neurosurgery. 2002;16(1):55-58.

Hårtel F. Die Leitungsanåsthesie und Injectionsbehandlung des Ganglion Gasseri und der Trigeminusståmme. Arch Klin Chir. 1912;100:193-292.

Ischia S., Luzzani A., Polati E. Retrogasserian glycerol injection: a retrospective study of 112 patients. Clin J Pain. 1990;6:291-296.

Isik N., Pamir M.N., Benli K., et al. Experimental trigeminal glycerol injection in dogs: histopathological evaluation by light and electron microscopy. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2002;79(2):94-106.

Jagia M., Bithal P.K., Dash H.H., et al. Effect of cerebrospinal fluid return on success rate of percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29(6):592-595.

Kondziolka D., Lunsford L.D. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia: technique and expectations. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;18(5):E7.

Kouzounias K., Lind G., Schechtmann G., et al. Comparison between balloon compression and glycerol rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurgery. 2010;113(3):486-492.

Linderoth B., Håkanson S. Paroxysmal facial pain in disseminated sclerosis treated by retrogasserian glycerol injection. Acta Neurol Scand. 1989;80:341-346.

Pal H.K., Dinda A.K., Roy S., Banerji A.K. Acute effect of anhydrous glycerol on peripheral nerve: an experimental study. Br Neurosurg. 1989;3:463-470.

Pieper D.R., Dickerson J., Hassenbuch S.J. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizolysis for treatment of chronic intractable cluster headaches: long-term results. Neurosurgery. 2000;46(2):363-370.

Pollock B.E. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy for patients with idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: a prospective analysis of factors related to pain relief. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(2):223-228.

Rappaport Z.H., Gomori J.M. Recurrent trigeminal cistern glycerol injections for tic douloureux. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1988;90:31-34.

Rengachary S.S., Watanabe I.S., Singer P., Bopp W.J. Effect of glycerol on peripheral nerve: an experimental study. Neurosurgery. 1983;13:681-688.

Slettebø H., Hirschberg H., Lindegaard K- F. Long-term results after percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy in patients with trigeminal neuralgia. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1993;117:231-235.

Stajcic Z. Evidence that the site of action of glycerol in relieving tic douloureux is its actual site of application. Dtsch Zahnartztl Z. 1990;45:44-46.

1. Leksell L. Trigeminusneuralgi: några neurofysiologiska aspekter och en ny behandlingsmetod. Lakartidningen. 1971;68:5145-5158.

2. Håkanson S., Leksell L. Stereotactic radiosurgery in trigeminal neuralgia. In: Pauser G., Gerstenbrand F., Gross D. Gesichtsschmerz: Schmerzstudien 2. New York: Gustav Fischer Verlag; 1979:231-237.

3. Jefferson A. Trigeminal root and ganglion injections using phenol in glycerine for relief of trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1963;26:345-352.

4. Håkanson S. Trigeminal neuralgia treated by the injection of glycerol into the trigeminal cistern. Neurosurgery. 1981;9:638-646.

5. Arias M.J. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia: a prospective study of 100 cases. J Neurosurg. 1986;65:32-36.

6. Dieckmann G., Veras G., Sogabe K. Retrogasserian glycerol injection or percutaneous stimulation in the treatment of typical and atypical trigeminal pain. Neurol Res. 1987;9:48-49.

7. Dieckmann G., Bockermann V., Heyer C., et al. Five-and-a-half years experience with percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy in treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Appl Neurophysiol. 1987;50:401-413.

8. Young R.F. Glycerol rhizolysis for treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:39-45.

9. Lunsford L.D., Bennett M.H., Martinez A.J. Experimental trigeminal glycerol injection: electrophysiologic and morphologic effects. Arch Neurol. 1985;42:146-149.

10. Sweet W.H. Glycerol rhizotomy. In: Youmans J.R., editor. Neurological Surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990:3908-3921.

11. Sweet W.H. Faciocephalic pain. In: Apuzzo M.L.J., editor. Brain Surgery: Complication Avoidance and Management. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1993:2053-2083.

12. Fujimaki T., Fukushima T., Miyazaki S. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol injection in the management of trigeminal neuralgia: long-term follow-up results. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:212-216.

13. Devor M., Govrin-Lippmann R., Rappaport Z.H. Mechanism of trigeminal neuralgia: an ultrastructural analysis of trigeminal root specimens obtained during microvascular decompression surgery. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(3):532-543.

14. Devor M., Amir R., Rappaport Z.H. Pathophysiology of trigeminal neuralgia: the ignition hypothesis. Clin J Pain. 2002;18(1):4-13.

15. Rappaport Z.H., Devor M. Trigeminal neuralgia: the role of self-sustaining discharge in the trigeminal ganglion. Pain. 1994;56(2):127-138.

16. Devor M. Chronic pain in the aged: possible relation between neurogenesis, involution and pathophysiology in adult sensory ganglia. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 1991;2(1-2):1-15.

17. Bunge R.P. Myelin degeneration in tissue culture. Neurosci Res Progr Bull. 1971;9:496-498.

18. Dulhunty A.F., Gage P.W. Differential effects of glycerol treatment on membrane capacity and excitation-contraction coupling in toad sartorius fibers. J Physiol (Lond). 1973;234:373-408.

19. Diechmann D. Glycerol-effects upon rabbits and rats. Indust Med. 1941;2:5-6.

20. Baxter B.W., Schacherl U. Experimental studies on the morphological changes produced by intrathecal phenol. CMAJ. 1962;86:1200.

21. King J.S., Jewett D.L., Sundberg H.R. Differential blockade of cat dorsal root C-fibers by various chloride solutions. J Neurosurg. 1972;36:569-583.

22. Robertson J.D. Structural alterations in nerve fibers produced by hypotonic and hypertonic solutions. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1958;4:349-364.

23. Pal H.K., Dinda A.K., Roy S., Banerji A.K. Acute effect of anhydrous glycerol on peripheral nerve: an experimental study. Br Neurosurg. 1989;3:463-470.

24. Freeman A.R., Reuben J.P., Brandt P.W., Grundfest H. Osmometrically determined characteristics of the cell membrane of squid and lobster giant axons. J Gen Physiol. 1966;50:423-445.

25. Håkanson S. Trigeminal Neuralgia Treated by Retrogasserian Injection of Glycerol. Stockholm: Karolinska Institute; 1982.

26. Rengachary S.S., Watanabe I.S., Singer P., Bopp W.J. Effect of glycerol on peripheral nerve: an experimental study. Neurosurgery. 1983;13:681-688.

27. Bremerich A., Reisert I. Die perineurale Leitungsblockade mit Glycerin und Phenol-Glycerin: eine histomorphologisch-morphome-trische Studie. Dtsch Zahnartztl Z. 1991;46:825-827.

28. Isik N., Pamir M.N., Benli K., et al. Experimental trigeminal glycerol injection in dogs: histopathological evaluation by light and electron microscopy. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2002;79(2):94-106.

29. Stajcic Z. Evidence that the site of action of glycerol in relieving tic douloureux is its actual site of application. Dtsch Zahnartztl Z. 1990;45:44-46.

30. Burchiel K.J., Russell L.C. Glycerol neurolysis: neurophysiological effects of topical glycerol application on rat saphenous nerve. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:784-788.

31. Rappaport Z.H., Seltzer Z., Zagzag D. The effect of glycerol on autotomy: an experimental model of neuralgia pain. Pain. 1986;26:85-91.

32. Sweet W.H., Poletti C.E., Macon J.B. Treatment of trigeminal neuralgia and other facial pains by retrogasserian injection of glycerol. Neurosurgery. 1981;9:647-653.

33. Sweet W.H., Poletti C.E. Problems with retrogasserian glycerol in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Appl Neurophysiol. 1985;48:252-257.

34. Sweet W.H. Retrogasserian glycerol injection as treatment for trigeminal neuralgia. In: Schmidek H.H., Sweet W.H. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. 2nd ed. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1988:1129-1137.

35. Bennett M.H., Lunsford L.D. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhi-zotomy for tic douloureux. II. Results and implications of trigeminal evoked potentials studies. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:431-435.

36. Bennett M.H., Jannetta P.J. Evoked potentials in trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 1983;13:242-247.

37. Raminsky M., Sears T.A. Internodal conduction in undissected demyelinated nerve fibers. J Physiol. 1972;227:323-350.

38. Waxman S.G., Brill M.H. Conduction through demyelinated plaque in multiple sclerosis: computer simulations of facilitation by short internodes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1978;69:39-45.

39. Fruhstorfer H., Lindblom U., Schmidt W.G. Method for quantitative estimation of thermal thresholds in patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1976;39:1071-1075.

40. Håkanson S. Surgical treatment: retrogasserian glycerol injection. In: Fromm G.H., Sessle B.J. Trigeminal Neuralgia: Current Concepts Regarding Pathogenesis and Treatment. Boston: ButterworthHeinemann; 1991:185-204.

41. Eide P.K., Stubhaug A. Sensory perception in patients with trigeminal neuralgia: effects of percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1997;68:207-211.

42. Kumar R., Mahapatra A.K., Dash H.H. The blink reflex before and after percutaneous glycerol rhizotomy in patients with trigeminal neuralgia: a prospective study of 28 patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;137:85-88.

43. Pandia M.P., Dash H.H., Bithal P.K., et al. Does egress of cerebrospinal fluid during percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy influence long-term pain relief? Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33:222-226.

44. Burchiel K.J. Percutaneons retrogasserian glycerol rhizolysis in the management of trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:361-366.

45. Hårtel F. Die Leitungsanåsthesie und Injectionsbehandlung des Ganglion Gasseri und der Trigeminusståmme. Arch Klin Chir. 1912;100:193-292.

46. Nugent G.R., Berry B. Trigeminal neuralgia treated by differential percutaneous radiofrequency coagulation of the gasserian ganglion. J Neurosurg. 1974;40:517-523.

47. Jho H.D., Lunsford L.D. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1997;8:63-74.

48. Håkanson S. Transoval trigeminal cisternography. Surg Neurol. 1978;10:137-144.

49. Shaw D.D., Bach-Gansmo T., Dahlström K. Iohexol: summary of North American and European clinical trials in adult lumbar, thoracic and cervical myelography with a new nonionic contrast medium. Invest Radiol. 1985;20(suppl):44-50.

50. Bergenheim A.T., Hariz M.I., Laitinen L.V. Selectivity of retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1991;56:159-165.

51. Bergenheim A.T., Hariz M.I., Laitinen L.V. Retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy and its selectivity in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Acta Neurochir (Wein). 1993;58(suppl):174-177.

52. Rappaport Z.H., Gomori J.M. Recurrent trigeminal cistern glycerol injections for tic douloureux. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1988;90:31-34.

53. Lunsford L.D.. Trigeminal neuralgia: treatment by glycerol rhizotomy, Wilkins R.H., Rengachary S.S., editors, Neurosurgery, New York, McGraw-Hill, 1985;vol. 3:2351-2356.

54. Håkanson S. Retrogasserian glycerol injection as treatment of tic douloureux. Adv Pain Res Ther. 1983;5:927-933.

55. North R.B., Kidd D.H., Piantadosi S., Carson B.S. Percutaneous retro-gasserian glycerol rhizotomy. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:851-856.

56. Saini S.S. Retrogasserian anhydrous glycerol injection therapy in trigeminal neuralgia: observations in 552 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50:1536-1538.

57. Steiger H.J. Prognostic factors in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: analysis of a differential therapeutic approach. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1991;113:11-17.

58. Waltz T.A., Dalessio D.J., Ott K.H., et al. Trigeminal cistern glycerol injections for facial pain. Headache. 1985;25:354-357.

59. Ischia S., Luzzani A., Polati E. Retrogasserian glycerol injection: a retrospective study of 112 patients. Clin J Pain. 1990;6:291-296.

60. Slettebø H., Hirschberg H., Lindegaard K- F. Long-term results after percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy in patients with trigeminal neuralgia. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1993;117:231-235.

61. Bergenheim A.T., Hariz M.I. Influence of previous treatment on outcome after glycerol rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:303-310.

62. Febles C., Werner-Wasik M., Rosenwasser R.H., et al. A comparison of treatment outcomes with gamma knife radiosurgery versus glycerol rhizotomy in the management of trigeminal neuralgia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57(suppl 2):253.

63. Blomstedt P.C., Bergenheim A.T. Technical difficulties and perioperative complications of retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurgery. 2002;79:168-181.

64. Jagia M., Bithal P.K., Dash H.H., et al. Effect of cerebrospinal fluid return on success rate of percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29(6):592-595.

65. Pollock B.E. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy for patients with idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: a prospective analysis of factors related to pain relief. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(2):223-228.

66. Henson C.F., Goldman H.W., Rosenwasser R.H., et al. Glycerol rhizotomy versus gamma knife radiosurgery for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: an analysis of patients treated at one institution. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(1):82-90.

67. Kondziolka D., Lunsford L.D. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia: technique and expectations. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;18(5):E7.

68. Jannetta P.J. Surgical treatment: microvascular decompression. In: Fromm G.H., Sessle B.J. Trigeminal Neuralgia: Current Concepts Regarding Pathogenesis and Treatment. Boston: ButterworthHeinemann; 1991:145-157.

69. Spaziante R., Cappabianca P., Graziussi G., et al. Percutaneous retro-gasserian glycerol rhizolysis for treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: results in 191 patients [Abstract]. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1992;117:97.

70. Lunsford L.D., Duma C.H. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizo-tomy: a ten-year experience [Abstract]. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1992;117:97.

71. Beck D.W., Olson J.J., Urig E.J. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhi-zotomy for treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1986;65:28-31.

72. Nabors M.W., Francis C.K., Kobrine A.I. Reactivation of herpesvirus in neurosurgical patients. Neurosurgery. 1986;19:599-603.

73. Nugent G.R. Surgical treatment: radiofrequency gangliolysis and rhizotomy. In: Fromm G.H., Sessle B.J. Trigeminal Neuralgia: Current Concepts Regarding Pathogenesis and Treatment. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1991:159-184.

74. Aspevall O., Hillebrant E., Linderoth B., Rylander M. Meningitis due to GemeUa hemolysans after neurosurgical treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Scand J Infect Dis. 1991;23:503-505.

75. Rushton J.G., Olafson R.A. Trigeminal neuralgia associated with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1965;13:383-386.

76. Brett D.C., Ferguson G.G., Ebers G.C., Paty D.W. Percutaneous trigeminal rhizotomy: treatment of trigeminal neuralgia secondary to multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1982;39:219-221.

77. Jensen T.S., Rasmussen P., Reske-Nielsen E. Association of trigeminal neuralgia with multiple sclerosis: clinical and pathological features. Acta Neurol Scand. 1982;65:182-189.

78. Chakravorty B.G. Association of trigeminal neuralgia with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1966;14:95-99.

79. Linderoth B., Håkanson S. Paroxysmal facial pain in disseminated sclerosis treated by retrogasserian glycerol injection. Acta Neurol Scand. 1989;80:341-346.

80. Broggi G., Franzini A. Radiofrequency trigeminal rhizotomy in treatment of symptomatic non-neoplastic facial pain. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:483-486.

81. Brisman R. Trigeminal neuralgia and multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1987;44:379-380.

82. Waltz T.A., Dalessio D.J., Copeland B., Abbott G. Percutaneous injection of glycerol for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Clin J Pain. 1989;5:195-198.

83. Lunsford L.D., Apfelbaum R.I. Choice of surgical therapeutical modalities for treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: microvascular decompression, percutaneous retrogasserian thermal or glycerol rhizotomy. Clin Neurosurg. 1985;32:319-333.

84. Rappaport Z.H. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol injection for trigeminal neuralgia: one year follow-up. Pain Clin. 1986;1:57-61.

85. Pieper D.R., Dickerson J., Hassenbuch S.J. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizolysis for treatment of chronic intractable cluster headaches: long-term results. Neurosurgery. 2000;46(2):363-370.

86. Ekbom K., Lindgren L., Nilsson B.Y., et al. Retro-gasserian glycerol injection in the treatment of chronic cluster headache. Cephalalgia. 1987;7:21-27.

87. Franzini A., Ferroli P., Leone M., Broggi G. Stimulation of the posterior hypothalamus for treatment of chronic intractable cluster headaches: first reported series. Neurosurgery. 2003;52(5):1095-1099.

88. Burns B., Watkins L., Goadsby P.J. Treatment of intractable chronic cluster headache by occipital nerve stimulation in 14 patients. Neurology. 2009;72:341-345.

89. Hannerz J., Linderoth B. Neurosurgical treatment of short-lasting, unilateral, neuralgiform hemicrania with conjunctival injection and tearing. Br J Neurosurgery. 2002;16(1):55-58.

90. Black D.F., Dodick D.W. Two cases of medically and surgically intractable SUNCT: a reason for caution and argument for a central mechanism. Cephalalgia. 2002;22(3):201-204.

91. Kouzounias K., Lind G., Schechtmann G., et al. Comparison of percutaneous balloon compression and glycerol rhizotomy for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurgery. 2010;113:486-493.