Chapter 28

Restrictive Cardiomyopathy

1. What is the basic physiologic problem in restrictive cardiomyopathy?

2. What are the main causes of restrictive cardiomyopathy?

Approximately half the cases of restrictive cardiomyopathy have an identifiable cause. The most common identifiable cause is myocardial infiltration from amyloidosis. Other infiltrative diseases include sarcoidosis, Gaucher disease, and Hurler disease. Storage diseases include hemochromatosis, glycogen storage disease, and Fabry disease. Endomyocardial involvement from endomyocardial fibrosis, radiation, and anthracycline treatment can also lead to restrictive cardiomyopathy. Although restrictive cardiomyopathy is a rather uncommon cause of heart failure in North America and Europe, it is a common cause of heart failure and death in tropical regions, including parts of Africa, Central and South America, India, and other parts of Asia (where the incidence of endomyocardial fibrosis is relatively high). Causes of restrictive cardiomyopathy are summarized in Table 28-1.

TABLE 28-1

CLASSIFICATION OF TYPES OF RESTRICTIVE CARDIOMYOPATHY ACCORDING TO CAUSE

Infiltrative

Amyloidosis

Sarcoidosis

Gaucher disease

Hurler disease

Fatty infiltration

Storage Disease

Hemochromatosis

Fabry disease

Glycogen storage disease

Endomyocardial

Endomyocardial fibrosis

Radiation

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (Löffler disease)

Carcinoid syndrome

Myocardial Noninfiltrative

Idiopathic cardiomyopathy

Familial cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Scleroderma

Modified from Kushwaha S, Fallon, JT, Fuster V: Restrictive cardiomyopathy, N Engl J Med 336:267-276, 1997.

3. What are the usual echocardiographic findings in restrictive cardiomyopathy?

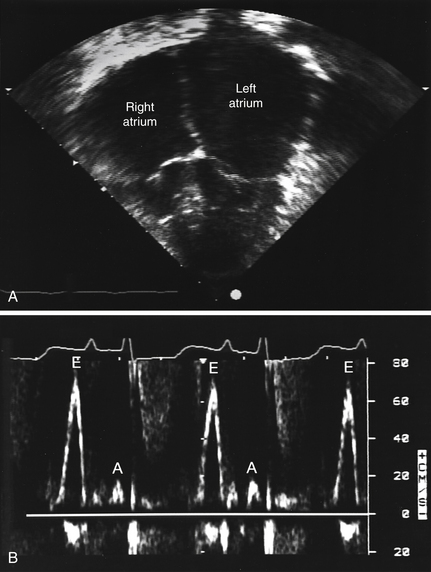

Echocardiography usually demonstrates normal or near-normal systolic function, ventricles of normal or decreased volumes, normal or only minimally increased ventricular wall thickness, impaired ventricular relaxation and filling (diastolic dysfunction), and biatrial enlargement. As discussed in Question 4, these findings may be different in later stages of amyloidosis and certain other conditions (Fig. 28-1, A). On Doppler echocardiography, one observes accentuated early diastolic filling of the ventricles (prominent E wave), shortened deceleration time, and diminished atrial filling (diminutive A wave) resulting in a high E-to-A wave ratio on the mitral inflow velocities (see Fig. 28-1, B).

Figure 28-1 Echocardiogram of a patient with familial restrictive cardiomyopathy. A, Apical 4-chamber view with dilated atria and normal ventricles. B, Mitral inflow pattern showing augmented early filling E waves (E) with shortened deceleration time and attenuated A waves (A) with minimal respiratory variation in velocity. (Modified from Schwartz ML, Colan SD: Familial restrictive cardiomyopathy with skeletal abnormalities. Am J Cardiol 92:636-639, 2003.)

4. How does amyloidosis affect the heart?

As with other organs, in amyloidosis there may be protein deposition in myocardial tissue. The term amyloidosis was reportedly coined by Virchow and means “starchlike.” The affected myocardium is found to be firm, rubbery, and noncompliant. This protein deposition leads to restrictive physiology, as well as to eventual systolic heart dysfunction and possible conduction abnormalities. Patients are often extremely fluid sensitive, and management is complicated by having to walk a fine line between volume overload and inadequate preload. Patients with amyloidosis often manifest orthostatic hypotension and may develop additional conduction-related disorders. The prognosis is generally extremely poor.

5. How is cardiac amyloidosis diagnosed?

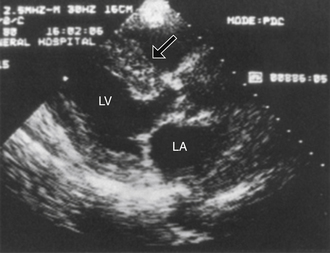

If the patient is not otherwise known to have amyloidosis, cardiac amyloidosis may be suggested by symptoms and signs of heart failure, an echocardiogram that demonstrates impaired filling and often thickened ventricular walls, a “sparkling” pattern on echocardiography (Fig. 28-2), and low voltage on the electrocardiogram (in spite of the thickened ventricular walls). Radionuclide imaging showing increased diffuse uptake of technetium-99m (99mTc) pyrophosphate and indium-111 (111In) antimyosin in cardiac amyloidosis can also be used to make the diagnosis. The diagnosis is usually confirmed, if necessary, by biopsy.

Figure 28-2 Echocardiogram demonstrating the sparkling pattern that can be seen in patients with cardiac amyloidosis. This sparkling pattern is best seen in this picture in the thickened ventricular septum (arrow). (Modified from Levine RA: Echocardiographic assessment of the cardiomyopathies. In Weyman AE: Principles and practice of echocardiography, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1994, Lea & Febiger, p 810.) LA, Left atrium; LV, left ventricle.

6. What are the main cardiac manifestations of sarcoidosis?

7. Is endomyocardial biopsy useful in cases of suspected restrictive cardiomyopathy?

Endomyocardial biopsy is considered reasonable in the setting of heart failure associated with unexplained restrictive cardiomyopathy (it is a class IIa, level-of-evidence C, recommendation in the scientific statement on endomyocardial biopsy by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/European Society of Cardiology [ACC/AHA/ESC]). Endomyocardial biopsy may reveal specific disorders, such as amyloidosis or hemochromatosis, or myocardial fibrosis and myocyte hypertrophy consistent with idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy. Endomyocardial biopsy should not be performed if computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggests the patient instead has pericardial constriction or if other less invasive tests and studies can identify a specific cause of the restrictive cardiomyopathy.

8. Is cardiac CT or cardiac MRI useful in cases of possible restrictive cardiomyopathy?

Both cardiac CT and cardiac MRI can be useful in cases of restrictive cardiomyopathy. Both imaging modalities can demonstrate a thickened pericardium, which may suggest constrictive pericarditis as the actual cause of the patient’s ailment. Cardiac MRI, with the use of delayed hyperenhancement in many cases, may demonstrate findings suggestive of sarcoidosis, eosinophilic endomyocardial disease, amyloidosis, and other causes of restrictive cardiomyopathy. Cardiac MRI can also be used to make the diagnosis of cardiac hemochromatosis. In some cases, MRI may also be used to guide endomyocardial biopsy and to assess the likelihood of obtaining diagnostic biopsy samples.

9. What are hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) and Löffler disease?

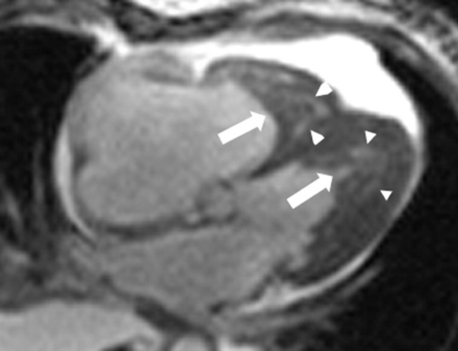

HES and Löffler (sometimes spelled “Loeffler”) disease are similar (and possibly the same) diseases characterized by persistent marked eosinophilia, absence of a primary cause of eosinophilia (e.g., parasitic or allergic disease), and eosinophil-mediated end-organ damage. The most common cardiac manifestation of HES is endomyocardial fibrosis, which was first described in the 1930s by Löffler. Secondary thrombosis may contribute to ventricular cavity obliteration, and thus these conditions are sometimes referred to as “restrictive obliterative cardiomyopathies” (Fig. 28-3). The reader should be aware that there is a confusing and variable use of the terms HES, Löffler disease, Löffler endomyocardial fibrosis, and endomyocardial fibrosis throughout the literature, with some authorities believing the syndromes are related and others treating them as distinct entities.

Figure 28-3 Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating endomyocardial fibrosis and intracardiac thrombus, partially obliterating the left and right ventricles. The long arrows point to ventricular thrombus; the arrow heads demonstrate areas of endomyocardial fibrosis. (Modified with permission from Salanitri GC: Endomyocardial fibrosis and intracardiac thrombus occurring in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol 184:1432-1433, 2005.)

11. How does Hurler syndrome affect the heart?

12. What are the clinical features of restrictive cardiomyopathy?

Reduced LV filling leads to reduced stroke volume resulting in low cardiac output symptoms such as fatigue and lethargy. Increased filling pressures cause pulmonary and systemic congestion and symptomatic dyspnea. On physical exam, the pulse may reflect low stroke volume with low amplitude and tachycardia. Jugular venous pulse is often elevated with prominent y descent consistent with rapid early ventricular filling. Inspiratory rise in venous pressure (the Kussmaul sign) may be seen. On heart exam, S3 gallop may be heard due to abrupt cessation of rapid ventricular filling.

13. What drugs can cause restrictive cardiomyopathy?

14. What is the prognosis of idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy?

15. What are the treatment options for idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy?

Symptomatic treatment includes loop diuretics to treat systemic and pulmonary venous congestion. Caution should be exercised, because patients are frequently extremely sensitive to alterations in LV volume. Heart-rate lowering agents such as calcium channel blockers and beta-adrenergic blocking agents (β-blockers) may improve diastolic function by increasing diastolic filling time. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) counteract compensatory neurohormonal changes of heart failure as well. Digoxin increases intracellular calcium, thus worsening diastolic function, and may increase the risks of arrhythmias, and should be used with caution. The development of atrial fibrillation leads to the loss of “atrial kick” and exacerbates ventricular filling perturbations. Maintenance of sinus rhythm, if possible, is thus desirable. As stroke volume tends to be fixed, bradyarrhythmias will lead to further decreases in cardiac output, and pacing of patients with bradycardia is often indicated. In patients with intractable heart failure, cardiac transplantation should be considered.

16. What are the hemodynamic findings on cardiac catheterization?

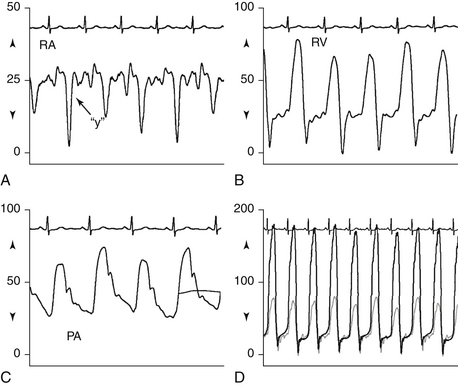

It may be difficult to distinguish restrictive cardiomyopathy from constrictive pericarditis in the catheterization laboratory. The diastolic “dip-and-plateau” or “square-root sign” and prominent y descent in right atrial (RA) pressure are seen in both conditions. Features more consistent with restriction include difference in ventricular diastolic pressure greater than 5 mm Hg, pulmonary artery (PA) systolic pressure greater than 50 mm Hg, ratio of right ventricular (RV) diastolic to systolic pressure of less than 1:3, and lack of ventricular interdependence with inspiration (Fig. 28-4).

Figure 28-4 Hemodynamics obtained from right heart catheterization in a patient with restrictive cardiomyopathy. Note A, prominent y descent on the RA waveform; B, “square-root” sign in diastole on the RV waveform; C, PA systolic pressure above 50 mm Hg; and D, systolic concordance and lack of ventricular interdependence. (Modified from Ragosta M: Pericardial disease and restrictive cardiomyopathy. In Ragosta M, editor: Textbook of clinical hemodynamics, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders, p. 144.) PA, Pulmonary artery; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Ammash, N.M., Tajik, A.J., Idiopathic Restrictive Cardiomyopathy. Basow D.S., ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: ***, 2013 UpToDate. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/idiopathic-restrictive-cardiomyopathy Accessed February 8, 2013

2. Arnold, J.M.O. Restrictive Cardiomyopathy. Available at: http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/cardiovascular_disorders/cardiomyopathies/restrictive_cardiomyopathy.html. Accessed February 8, 2013

3. Cooper, L.T., Definition and Classification of the Cardiomyopathies. Basow D.S., ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: ***, 2013 UpToDate. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/definition-and-classification-of-the-cardiomyopathies Accessed February 8, 2013

4. Cooper, L.T., Baughman, K., Feldman, A.M., et al. AHA/ACC/ESC joint scientific statement: the role of endomyocardial biopsy in the management of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2007;116:2216–2233.

5. Hare, J.M. The dilated, restrictive, and infiltrative cardiomyopathies. In Libby P., Bonow R.O., Mann D.L., Zipes D.P., eds.: Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, ed 9, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2012. pp. 1571-1578

6. Kushwaha, S.S., Fallon, J.T., Fuster, V. Restrictive cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 1997;335:267–276.

7. Murarka, S., Movahed, M.R. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail. 2010;16:971–979.

8. Ragosta, M. Pericardial disease and restrictive cardiomyopathy. In: Ragosta M., ed. Textbook of clinical hemodynamics. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2008. pp. 136-146

9. Viccellio, A.W. Restrictive cardiomyopathy. Available at: http://www.emedicine.com. Accessed February 8, 2013