CHAPTER 2 Respiratory system

Assessing The Airway

History and examination

Predictive tests

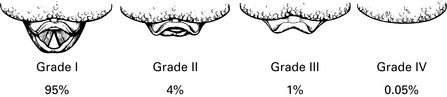

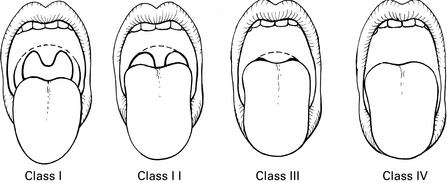

Mallampati classification (Mallampati et al 1985)

The patient sits upright with the head in the neutral position and the mouth open as wide as possible, with the tongue extended to maximum. The following structures are visible (Fig. 2.2):

Class I view is grade I intubation >99% of the time. Class IV view is grade III or IV intubation 100% of the time.

This classification may fail to predict >50% of difficult intubations.

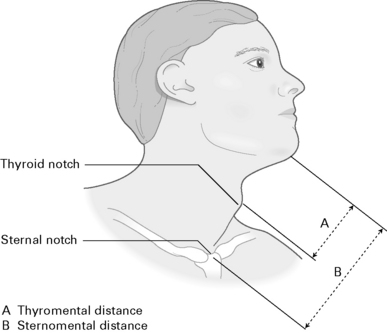

Thyromental distance (Patil et al 1983)

Measure from the upper edge of the thyroid cartilage to tip of the jaw with the head fully extended (Fig. 2.3). A short thyromental distance equates with an anterior larynx which is at a more acute angle and also results in less space for the tongue to be compressed into by the laryngoscope blade. This is a relatively unreliable test unless combined with other tests:

Sternomental distance (Savva 1994)

Measure from the sternum to the tip of the mandible with the head extended (Fig. 2.3). A sternomental distance of ≤12.5 cm predicts difficult intubation.

Horizontal length of mandible

Horizontal mandibular length >9 cm is suggestive of a good laryngoscopic view.

Wilson risk score (Wilson 1993; see Table 2.1)

| Parameter | Risk level |

|---|---|

| Weight | 0–2 (e.g. >90 kg = 1; >110 kg = 2) |

| Head and neck movement | 0–2 |

| Jaw movement | 0–2 |

| Receding mandible | 0–2 |

| Buck teeth | 0–2 |

| Maximum | 10 points |

Radiographic predictors of difficult intubation

These have the disadvantage of X-ray exposure and thus cannot be performed as routine tests.

Combined indicators

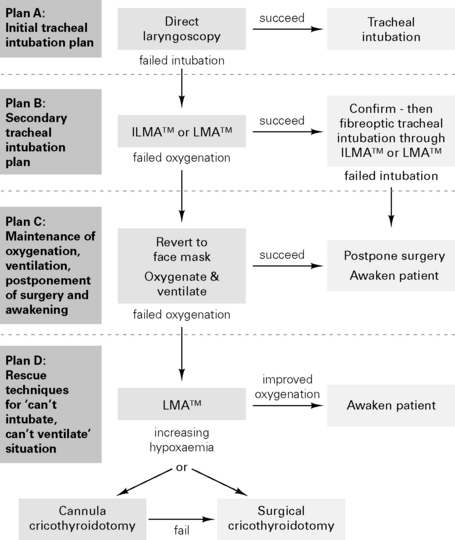

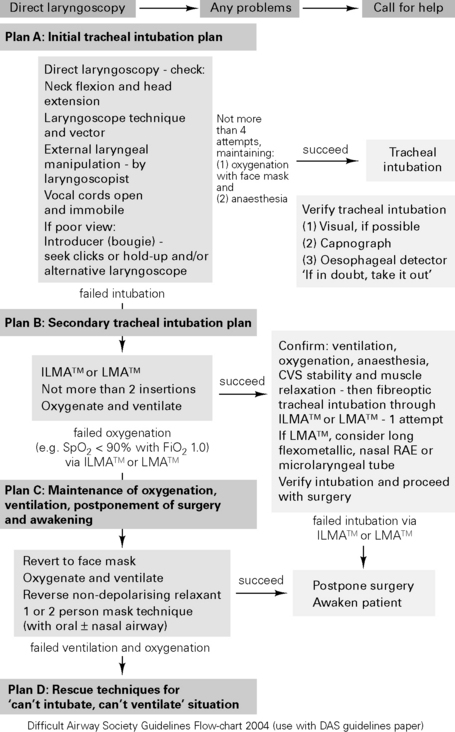

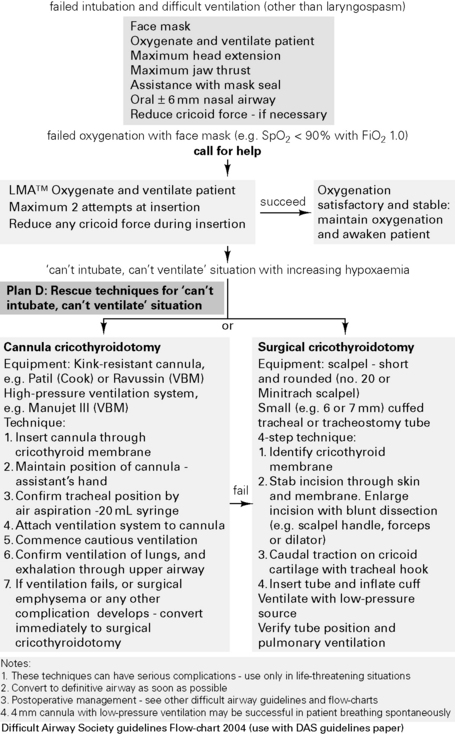

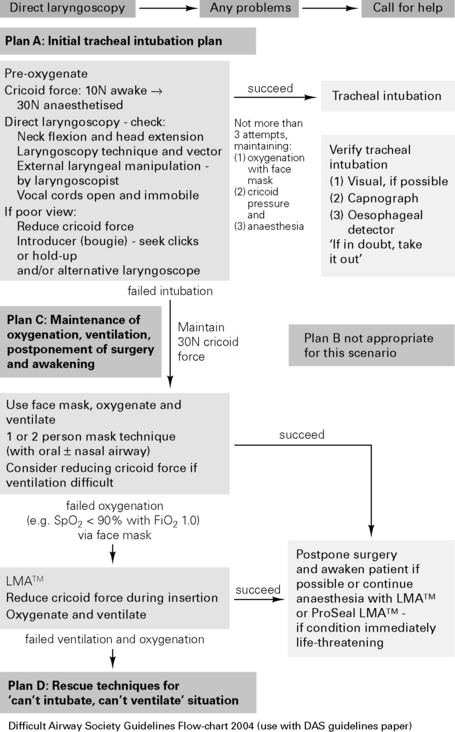

Difficult Airway Society Guidelines for Management of the Unanticipated Difficult Intubation 2004

Problems with tracheal intubation are the most frequent cause of anaesthetic death in the analyses of records of the UK medical defence societies. The Difficult Airway Society (DAS) has developed guidelines for management of the unanticipated difficult intubation in an adult non-obstetric patient, see http://www.das.uk.com/home

Arné J., Descoins P., Ingrand P., et al. Preoperative assessment for difficult intubation in general and ENT surgery: predictive value of a clinical multivariate risk index. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:140-146.

Benumof J.L. Management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:1087-1110.

Cass N.M., James N.R., Lines V. Difficult laryngoscopy complicating intubation for anaesthesia. BMJ. 1956;1:488-489.

Charters P. What future is there for predicting difficult intubation? Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:309-311.

Chou H.C., Wu T.L. Mandibulohyoid distance in difficult laryngoscopy. Br J Anaesth. 1993;71:335-339.

Cormack R.S., Lehane. Difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia. 1984;39:1105-1111. Difficult Airway Society, 2004, British Airway Society Guidelines Flow-chart 2004, http://www.das.uk.com/files/rsi-Jul04-A4.pdf.

Freck C.M. Predicting difficult intubation. Anaesthesia. 1991;46:1005-1008.

Henderson J.J., Popat M.T., Latto I.P., et al. Difficult Airway Society guidelines for management of the unanticipated difficult intubation. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:675-694.

Lavery G.G., McCloskey B.V. The difficult airway in adult critical care. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2163a-2173a.

Lee A., Fan L.T.Y., Gin T., et al. A systematic review (meta-analysis) of the accuracy of the Mallampati tests to predict the difficult airway. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1867-1878.

Mallampati S.R., Gatt S.P., Gugino L.D., et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult intubation: a prospective study. Can J Anaesth. 1985;32:429-434.

Nichol H.L., Zuck D. Difficult laryngoscopy – the ‘anterior’ larynx and the atlanto-occipital gap. Br J Anaesth. 1983;55:141-143.

Patil V.U., Stehling L.C., Zaunder H.L. Fibreoptic endoscopy in anaesthesia. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers, 1983.

Popat M. The airway. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:1166-1170.

Savva D. Prediction of difficult tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth. 1994;73:149-153.

Vaughan R.S. Predicting difficult airways. BJA CEPD Reviews. 2001;1:44-47.

White A., Kander P.L. Anatomical factors in difficult direct laryngoscopy. Br J Anaesth. 1975;47:468-474.

Wilson M.E. Predicting difficult intubation. Br J Anaesth. 1993;71:333-334.

Anaesthesia And Respiratory Disease

Smoking

Effects of smoking

Preoperative cessation of smoking (Box 2.1)

A study in patients undergoing CABG (Warner 2006) showed that in those stopping smoking, the incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications did not fall until at least 8 weeks had elapsed:

Box 2.1 Effects of cessation of smoking

| 12–24 h | Clearance of carbon monoxide |

| 2–10 days | Decreased upper airway reactivity |

| 1–2 months | Increase in postoperative pulmonary complications (Bluman et al 1998) |

| 6 months | Decrease in postoperative pulmonary complications |

| Years | Reduced risk of COPD, ischaemic heart disease, lung cancer and cerebrovascular disease |

Chronic bronchitis

Chronic bronchitis is defined as productive cough >3 months of the year for ≥2 years.

Effects of general anaesthesia

ratios. Increased shunting (shunt fraction during GA: 11% during spontaneous breathing, 14% during IPPV)

ratios. Increased shunting (shunt fraction during GA: 11% during spontaneous breathing, 14% during IPPV)All these factors result in an increased A–aO2 (difference in alveolar and arterial oxygen tensions), which persists for at least 1–2 h postoperatively. Diaphragm may recover from neuromuscular blockade prior to muscles involved in coughing and swallowing. Postoperative wound pain, abdominal distension, pulmonary venous congestion and a supine posture all increase CC–FRC and result in further alveolar collapse.

Anaesthesia for chronic respiratory disease

Anaesthetic techniques

Aims

Use either regional/local technique or maximal support approach with GA. Plan elective surgery for summer.

Anaesthesia for asthmatics

Reversal

Anticholinesterases cause bronchospasm, prevented by the addition of an anticholinergic.

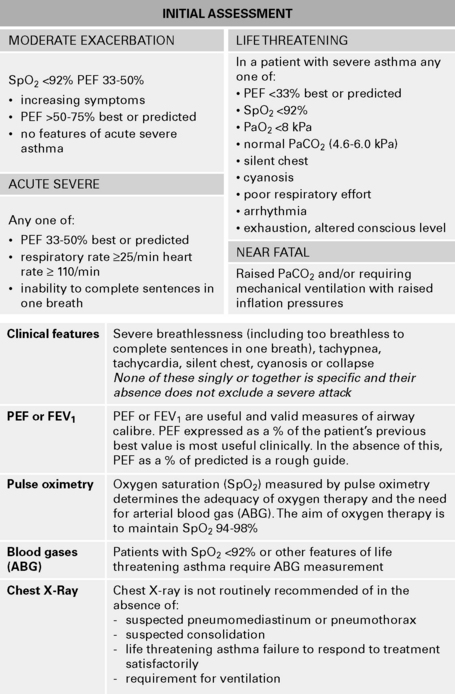

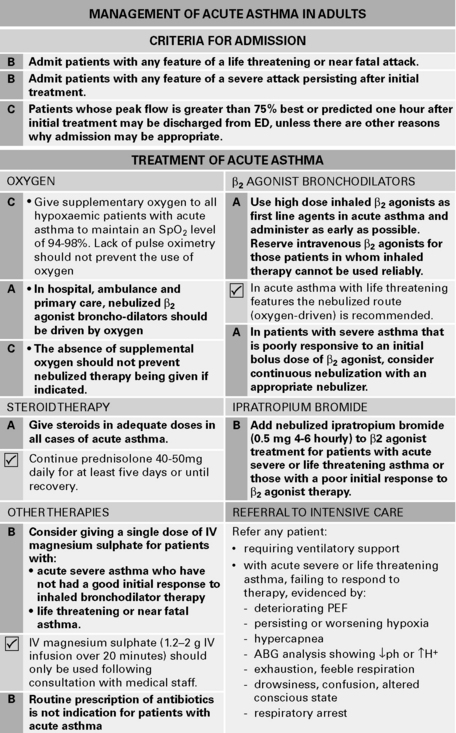

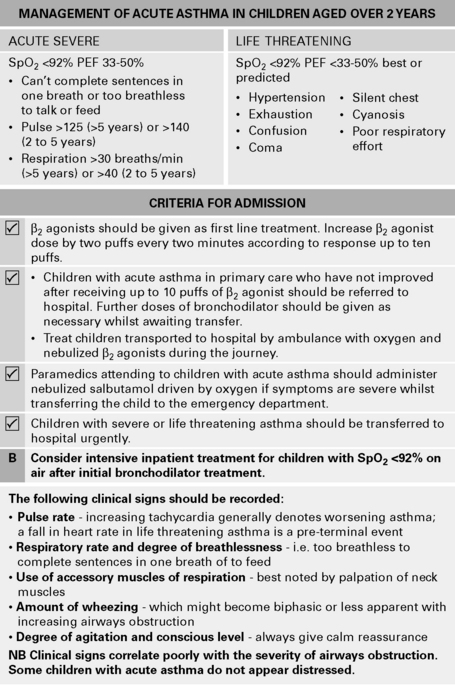

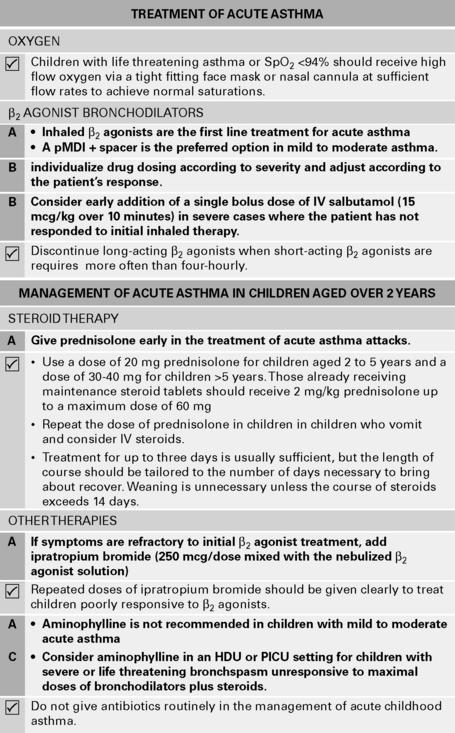

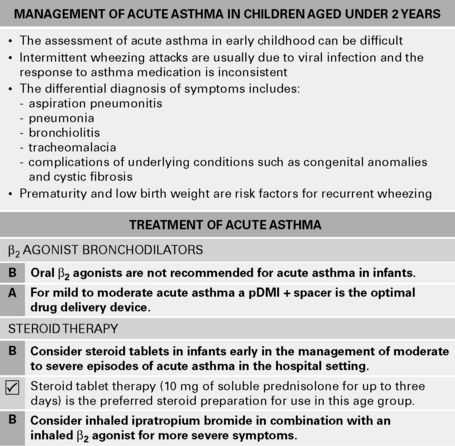

Figure 2.8 (A) British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. Management of Acute Asthma in Adults. (British Thoracic Society & Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2009.) (B) British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. Management of Acute Asthma in Children aged over 2 years. (British Thoracic Society & Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2009.) (C) British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. Management of Acute Asthma in Children aged under 2 years.

(British Thoracic Society & Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2009.)

Postoperative hypoxia

Recommendations (Powell et al 1996) include:

Bluman L.G., Mosca L., Newman N., et al. Preoperative smoking habits and postoperative pulmonary complications. Chest. 1998;113:883-889.

British Thoracic Society & Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British Guideline on the Management of Asthma, 2009 www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/ClinicalInformation/Asthma/AsthmaGuidelines/tabid/83/Default.aspx.

Edrich T., Sadovnikoff N. Anesthesia for patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009. E-pub doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328331ea5b

Mills G.H. Respiratory physiology and anaesthesia. BJA CEPD Rev. 2001;1:35-39.

Powell J.F., Menon D.K., Jones J.G. The effects of hypoxaemia and recommendations for postoperative oxygen therapy. Anaesthesia. 1996;51:769-772.

Stanley D., Tunnicliffe W. Management of life-threatening asthma in adults. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain. 2008;8:95-99.

Stather D.R., Stewart T.E. Clinical review: mechanical ventilation in severe asthma. Crit Care. 2005;9:581-587.

Sweeney B.P., Grayling M. Smoking and anaesthesia: the pharmacological implications. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:179-186.

Tonnesen H., Nielsen P.R., Lauritzen J.B., et al. Smoking and alcohol intervention before surgery: evidence for best practice. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:297-306.

Vaschetto R., Bellotti E., Turucz E., et al. Inhalational anesthetics in acute severe asthma. Curr Drug Targets. 2009;10:826-832.

Walsh T.S., Young C.H. Anaesthesia and cystic fibrosis. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:614-622.

Warner D.O. Perioperative Abstinence from Cigarettes: Physiologic and Clinical Consequences. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:356-367.

Thoracic Anaesthesia

Anaesthesia for thoracotomy

Lung function tests

Anaesthesia for one-lung ventilation

Physiology of two-lung IPPV in lateral decubitus position

Maintain two-lung ventilation until pleura is opened.

Double-lumen tubes

The following are types of double-lumen tube:

Carlens and White tubes have lumens of a smaller diameter than the Robertshaw tubes.

Insertion of tube with carinal hook

Anaesthesia for bronchopleural fistula

Aim for early extubation to avoid pressure from IPPV on stump sutures.

Anaesthesia for lung cysts/bullae

Good postoperative pain relief (e.g. epidural) allows quicker return of normal lung function.

Anaesthesia for bronchoscopy

Methods of anaesthesia for bronchoscopy include:

Complications include dental and laryngeal damage, tracheal rupture, haemorrhage and pneumothorax.

Eastwood J., Mahajan R. One-lung anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth CEPD Rev. 2002;2:83-87.

Grichnik K.P., Shaw A. Update on one-lung ventilation: the use of continuous positive airway pressure ventilation and positive end-expiratory pressure ventilation – clinical application. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22:23-30.

Hillier J., Gillbe C. Anesthesia for lung volume reduction surgery. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:1210-1219.

Karzai W., Schwarzkopf K. Hypoxemia during one-lung ventilation: prediction, prevention, and treatment. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1402-1411.

Slinger P. Update on anesthetic management for pneumonectomy. Curr Opin Anaesth. 2009;22:31-37.

Tschernko E.M., Kritzinger M., Gruber E.M., et al. Lung volume reduction surgery: preoperative functional predictors for post-operative outcome. Anesth Analges. 1999;88:28-33.

Vaughan R.S. Pain relief after thoracotomy. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:681-683.

Mechanical Ventilation

Mechanical ventilation

Ventilatory modes

High-frequency ventilation

Positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP)

Effects of PEEP

Other ventilatory modes

Weaning from ventilation

The following criteria must first be met:

CROP index

The threshold value predicting successful weaning was 13 mL/breath per min, giving a sensitivity of 0.81 and a specificity of 0.57.

Other factors to be considered:

Bouchut J.-C., Godard J., Claris O. High frequency oscillatory ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1007-1012.

Edwards S.M., Matthews P.C. Current modes of conventional ventilation in intensive care. Br J Anaesth CEPD Rev. 2002;2:41-44.

Hawker F.F. PEEP and CPAP. Curr Anaesth Crit Care. 1996;7:236-242.

Lia Graciano A., Freid E.B. High-frequency oscillatory ventilation in infants and children. Curr Opin Anesth. 2002;15:161-166.

Shelly M.P., Nightingale P. ABC of intensive care: respiratory support. BMJ. 1999;318:1674-1677.

Soni N., Williams P. Positive pressure ventilation: what is the real cost? Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:446-457.

Stocker R., Biro P. Airway management and artificial ventilation in intensive care. Curr Opin Anesth. 2005;18:35-45.

Sydow M., Burchardi H. Inverse ratio ventilation and airway pressure release ventilation. Curr Opin Anaesth. 1997;9:523-528.

<50% = high risk (obstructive pattern)

<50% = high risk (obstructive pattern)

<50% = high risk (restrictive pattern)

<50% = high risk (restrictive pattern)

mismatch but may be unavoidable, particularly in children with poor venous access. Coughing and laryngospasm are common. Pre-oxygenate to avoid desaturation. Ketamine increases secretions and is relatively contraindicated. Aim to intubate for most procedures to allow tracheobronchial suctioning and control of ventilation. Ensure adequate depth of anaesthesia prior to intubation in view of bronchial hyperreactivity. Low airway pressures reduce the risk of pneumothorax.

mismatch but may be unavoidable, particularly in children with poor venous access. Coughing and laryngospasm are common. Pre-oxygenate to avoid desaturation. Ketamine increases secretions and is relatively contraindicated. Aim to intubate for most procedures to allow tracheobronchial suctioning and control of ventilation. Ensure adequate depth of anaesthesia prior to intubation in view of bronchial hyperreactivity. Low airway pressures reduce the risk of pneumothorax. mismatch, diffusion hypoxia, aspiration or central or obstructive apnoea.

mismatch, diffusion hypoxia, aspiration or central or obstructive apnoea. <100 ⇒ postoperative IPPV necessary.

<100 ⇒ postoperative IPPV necessary. mismatch.

mismatch. mismatch is improved by nursing the patient in a lateral position with the healthy lung lowermost if breathing spontaneously, or the healthy side uppermost if IPPV.

mismatch is improved by nursing the patient in a lateral position with the healthy lung lowermost if breathing spontaneously, or the healthy side uppermost if IPPV.

scatter

scatter

ratios, ↑ venous admixture

ratios, ↑ venous admixture mismatch

mismatch