CHAPTER 5 RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

INTERPRETATION OF BLOOD GASES

Most ICUs now have a blood gas analyser for ‘point of care testing’ (POCT). These are expensive to maintain and repair. You will be unpopular if you damage it by, for example, blocking the sample channels with clotted blood. If you do not know how to use it, ask for help. Normal blood gas values are as shown in Table 5.1.

| pH | 7.35–7.45 |

| PaO2 | 13 kPa |

| PaCO2 | 5.3 kPa |

| HCO3 | 22–25 mmol/L |

| Base deficit or excess | −2 to +2 mmol/L |

Note the inspired oxygen concentration (FiO2). The higher the FiO2 required to achieve any given PaO2 the more significant the problem (see below).

Note the inspired oxygen concentration (FiO2). The higher the FiO2 required to achieve any given PaO2 the more significant the problem (see below). Look again at the PaCO2. Is the PaCO2 consistent with the change in pH, i.e. if the patient is acidotic, is the PaCO2 raised? If the patient is alkalotic, is the PaCO2 low? If so the primary abnormality is likely to be respiratory.

Look again at the PaCO2. Is the PaCO2 consistent with the change in pH, i.e. if the patient is acidotic, is the PaCO2 raised? If the patient is alkalotic, is the PaCO2 low? If so the primary abnormality is likely to be respiratory. If the PaCO2 is normal or does not explain the abnormality in pH, look at the base deficit / base excess.

If the PaCO2 is normal or does not explain the abnormality in pH, look at the base deficit / base excess. If the base deficit / base excess is consistent with the abnormality in pH then the primary abnormality is metabolic.

If the base deficit / base excess is consistent with the abnormality in pH then the primary abnormality is metabolic. If both the PaCO2 and the base excess/base deficit are both altered in a way that is consistent with the abnormality in pH then a mixed picture is present.

If both the PaCO2 and the base excess/base deficit are both altered in a way that is consistent with the abnormality in pH then a mixed picture is present. If the PaCO2 and base excess / deficit are both altered in such a way that one is consistent with the change in pH and the other is not, then it is likely that a compensated acidosis / alkalosis is present (see descriptions below).

If the PaCO2 and base excess / deficit are both altered in such a way that one is consistent with the change in pH and the other is not, then it is likely that a compensated acidosis / alkalosis is present (see descriptions below).A number of patterns of disturbance of acid–base balance are recognized.

Respiratory acidosis

Hypoventilation from any cause results in accumulation of CO2 and respiratory acidosis. Over time, the bicarbonate concentration may rise (base excess) in an attempt to balance this and a compensated respiratory acidosis may develop, in which the pH is nearly normal.

DEFINITIONS OF RESPIRATORY FAILURE

Type 1 (hypoxic) respiratory failure

PaO2 < 8 kPa with normal or low PaCO2

Type 1 respiratory failure is caused by disease processes that directly impair alveolar function, e.g. pneumonia, pulmonary oedema, adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and fibrosing alveolitis. Progressive hypoxaemia is accompanied initially by hyperventilation. The physiological benefit of hyperventilation is that it lowers alveolar carbon dioxide tension and allows for a modest increase in alveolar oxygen concentration, as can be demonstrated from the alveolar gas equation:

Type 2 (hypercapnic) respiratory failure

PaO2 < 8 kPa and PaCO2 > 8 kPa

Quantifying the degree of hypoxia

The definitions above relate to patients breathing air at normal atmospheric pressure. When interpreting blood gases the inspired oxygen concentration (FiO2) must be known. Clearly a patient who is already receiving significant oxygen therapy and still has poor PaO2 is considerably worse than a patient with the same PaO2 on air. For this reason, PaO2/FiO2 ratio, alveolar–arterial (A–a) gradient, and shunt fraction (see below) have all been used to describe the severity of hypoxia.

Normal and abnormal values for PaO2/FiO2 ratio, A–a gradient and shunt fraction are shown in Table 5.2.

| Normal | Severe hypoxia | |

|---|---|---|

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | >40 kPa | <27 kPa |

| A–a gradient* | <26 kPa | &45 kPa |

| Shunt fraction | 0–8% | >30% |

MANAGEMENT OF RESPIRATORY FAILURE

Common causes of respiratory failure are listed in Table 5.3.

| Loss of respiratory drive | CVA/brain injury Metabolic encephalopathy Effects of drugs |

| Neuropathy and neuromuscular conditions | Critical illness neuropathy Spinal cord injury Phrenic nerve injury Guillain–Barré syndrome Myasthenia gravis |

| Chest wall abnormality | Trauma Scoliosis |

| Airway obstruction | Foreign body Tumour Infection Sleep apnoea |

| Lung pathology | Asthma Pneumonia COPD Acute and chronic fibrosing conditions ALI/ARDS |

Is the patient using accessory muscles of respiration and making adequate respiratory effort, or exhausted with minimal respiratory effort? Is there an adequate cough?

Is the patient using accessory muscles of respiration and making adequate respiratory effort, or exhausted with minimal respiratory effort? Is there an adequate cough? If possible, take a history. If the patient is too short of breath to talk, the history may be obtained from the notes, staff or relatives. Try to obtain some idea of the patient’s normal respiratory reserve. How far can the patient walk? Are they oxygen dependent? Can they leave the house?

If possible, take a history. If the patient is too short of breath to talk, the history may be obtained from the notes, staff or relatives. Try to obtain some idea of the patient’s normal respiratory reserve. How far can the patient walk? Are they oxygen dependent? Can they leave the house? Examine the patient, particularly the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, bearing in mind the causes of respiratory failure. Note:

Examine the patient, particularly the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, bearing in mind the causes of respiratory failure. Note:

If there is wheeze, peak flow measurement may help to document severity but is often unrecordable in the critically ill.

If there is wheeze, peak flow measurement may help to document severity but is often unrecordable in the critically ill.Management is based around correction of hypoxia, ventilatory support if required, and treatment of the underlying condition.

Hypoxaemia

Hypoxaemia is the primary concern and should be corrected:

If there is evidence of chronic CO2 retention, (raised bicarbonate on blood gas) give controlled oxygen therapy 24–28%, via a Venturi system. While it may be appropriate to give higher oxygen concentrations this should only be done in a controlled environment where advanced respiratory support and close observation are available (see COPD, p. 152).

If there is evidence of chronic CO2 retention, (raised bicarbonate on blood gas) give controlled oxygen therapy 24–28%, via a Venturi system. While it may be appropriate to give higher oxygen concentrations this should only be done in a controlled environment where advanced respiratory support and close observation are available (see COPD, p. 152).Treatment of the underlying condition

Bronchodilators. If there is wheeze, nebulized salbutamol may help. In more severe cases consider intravenous bronchodilators and steroids (see Asthma, p. 149).

Bronchodilators. If there is wheeze, nebulized salbutamol may help. In more severe cases consider intravenous bronchodilators and steroids (see Asthma, p. 149). Physiotherapy may help clear secretions and re-expand areas of collapse. If possible sit patients upright or in a chair.

Physiotherapy may help clear secretions and re-expand areas of collapse. If possible sit patients upright or in a chair. Antibiotic therapy is best directed on the basis of Gram stains of sputum and on subsequent culture results. Seek microbiological advice. In the first instance broad-spectrum cover, e.g. with a cephalosporin is reasonable. A macrolide antibiotic such as clarithromycin should be added if there is a possibility of an atypical chest infection (see Pneumonia, p. 141).

Antibiotic therapy is best directed on the basis of Gram stains of sputum and on subsequent culture results. Seek microbiological advice. In the first instance broad-spectrum cover, e.g. with a cephalosporin is reasonable. A macrolide antibiotic such as clarithromycin should be added if there is a possibility of an atypical chest infection (see Pneumonia, p. 141). Diuretics. If there is evidence of congestive cardiac failure and pulmonary oedema, then diuretics may help. Frusemide (furosemide) 40 mg or bumetanide 1–2 mg i.v.

Diuretics. If there is evidence of congestive cardiac failure and pulmonary oedema, then diuretics may help. Frusemide (furosemide) 40 mg or bumetanide 1–2 mg i.v. Intravenous or nebulized steroids, nebulized adrenaline and helium oxygen mix may be of value in upper airway obstruction.

Intravenous or nebulized steroids, nebulized adrenaline and helium oxygen mix may be of value in upper airway obstruction.Continually reassess response to treatment. If there is no improvement or if the patient’s condition worsens, tracheal intubation and assisted ventilation may become necessary. Possible indications for intervention are shown in Box 5.1.

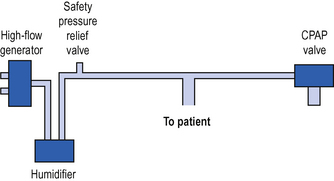

CONTINUOUS POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE (CPAP)

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is a system for spontaneously breathing patients which is analogous to PEEP in ventilated patients (see p. 126). It may be provided either through a tight-fitting face mask or via connection to an endotracheal / tracheostomy tube. Newly developed full hood systems are useful for the claustrophobic / confused patient. A high gas flow (which must be greater than the patient’s peak inspiratory flow rate) is generated in the breathing system. A valve on the expiratory port ensures that pressure in the system, and the patient’s airways, never falls below the set level. This is usually +5 to +10 cm H2O (Fig. 5.1).

NON-INVASIVE POSITIVE PRESSURE VENTILATION

Biphasic positive airways pressure (BIPAP)

The most commonly used form of NIPPV is biphasic positive airway pressure (BIPAP). A high flow of gas is delivered to the airway via a tight fitting face or nasal mask, to create a positive pressure (see CPAP above). The ventilator alternates between higher inspiratory and lower expiratory pressures. The higher inspiratory pressure augments the patient’s own respiratory effort and increases tidal volume, while the lower expiratory pressure is analogous to CPAP / PEEP. Typical initial settings are shown in Table 5.4.

TABLE 5.4 Typical initial settings for BIPAP non-invasive ventilation

| Inspiratory pressure (IPAP) | 10–12 cm H2O |

| Expiratory pressure (EPAP) | 4–5 cm H2O |

| Inspiratory time (It) | 1–2 s |

| FiO2 | As required to maintain oxygen saturation |

Once established, the inspiratory pressure and inspiratory time can be adjusted to create the optimal ventilatory pattern for the patient.

INVASIVE VENTILATION

Volume controlled ventilation

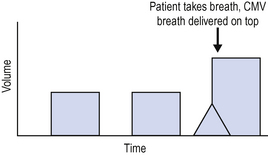

The simplest form of volume controlled ventilation is controlled mandatory ventilation (CMV) (Fig. 5.2).

The patient is ventilated at a preset tidal volume and rate (for example, tidal volume 500 mL and rate 12 breaths/min). The tidal volume delivered is therefore predetermined and the peak pressure required to deliver this volume varies depending upon other ventilator settings and the patient’s pulmonary compliance. One disadvantage, therefore, of volume controlled modes of ventilation is that high peak airway pressures may result and this can lead to lung damage or barotrauma.

Pressure controlled ventilation

It is important when using pressure controlled ventilation to understand the relationship between rate, inspiratory time and the I:E ratio (ratio of inspiratory time to expiratory time). Rate determines the total time period for each breath (60 s divided by rate = duration in seconds for each breath). The I:E ratio then determines how this time is apportioned between inspiration and expiration.

If respiratory rate is 10/min, total time for breath 60/10 s = 6 s.

If I:E ratio 1:2, then inspiratory time = 2 s and expiratory time = 4 s.

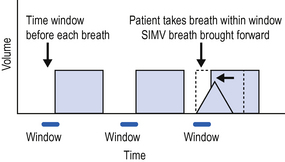

Synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV)

Although historically a volume controlled mode of ventilation, the equivalent of SIMV is now available in both volume controlled and pressure controlled modes (Fig. 5.3). Immediately before each breath there is a small time window during which the ventilator can recognize a spontaneous breath and respond by delivering the set (SIMV) breath early.

Pressure support / assisted spontaneous breathing (ASB)

Breathing through a ventilator can be difficult because respiratory muscles may be weak and ventilator circuits and tracheal tubes provide significant resistance to breathing. These problems can be minimized by the provision of pressure support. The ventilator senses a spontaneous breath and augments it by addition of positive pressure. This reduces the patient’s work of breathing and helps to augment the tidal volume. Pressure support modes are available on all modern ventilators and can be used in conjunction with both volume and pressure controlled modes of ventilation.

Triggering

Both SIMV and pressure support modes of ventilation require the ventilator to be able to detect the patient’s own respiratory effort in order to trigger the appropriate ventilator response. Historically triggering was achieved by detection of pressure changes in the circuit. There was no gas flow in the breathing circuit between ventilator delivered breaths and the patient’s inspiratory effort was detected as a drop in pressure in the breathing circuit. This was an inefficient method of triggering which was uncomfortable and exhausting for patients. Modern ventilators rely on flow triggering. There is a constant low level of gas flow in the circuit at all times. Flow sensors detect small changes in flow in the circuit in response to spontaneous respiratory effort by the patient, triggering the appropriate ventilator response. This is a more efficient and comfortable method of triggering.

VENTILATION STRATEGY AND VENTILATOR SETTINGS

Ventilation strategy

In most patients an SIMV volume controlled mode of ventilation with added pressure support will be adequate. Typical initial ventilator settings for an adult are as shown in Table 5.5.

TABLE 5.5 Typical ventilator settings (SIMV, volume control and pressure support)

| Tidal volume | 6–10 mL/kg |

| Rate | 8–14 breaths/min |

| I:E ratio | 1:2 |

| PEEP | 5–10 cm H2O |

| Pressure support | 15–20 cm H2O |

| FiO2 | As required to maintain oxygenation |

Pressure controlled ventilation can be used for all patients, although it is frequently reserved for those with poor pulmonary compliance (see ALI, p. 154). Typical initial settings are as shown in Table 5.6.

TABLE 5.6 Typical ventilator settings (SIMV, pressure control and pressure support)

| Peak inspiratory pressure | 20–35 cm H2O |

| Rate | 8–14 breaths/min |

| Inspiratory time | 1.5–2 s |

| PEEP | 5–10 cm H2O |

| Pressure support | 15–20 cm H2O |

| FiO2 | As required to maintain oxygenation |

CARE OF THE VENTILATED PATIENT

Ventilator care bundles

The ventilator care bundle is designed to reduce the incidence of ventilator associated pneumonia and other complications with their attendant prolongation of intensive care unit stay and increased mortality (NICE National patient safety agency. Technical patient safety solutions for ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults 2008. www.nice.org.uk/guidelines). The elements of the ventilator care bundle are:

In addition, a number of other factors are important in the ventilated patient.

Monitoring

Tidal volume and minute volume delivered and expired. A discrepancy between the two indicates a leak in the circuit.

Tidal volume and minute volume delivered and expired. A discrepancy between the two indicates a leak in the circuit. Peak airway pressure. If the peak airway pressure does not reach a predetermined value, the breathing circuit may have become disconnected. If the peak pressure is too high this may indicate obstruction of the airway or breathing circuit, or poor compliance. The patient may be at risk of barotrauma.

Peak airway pressure. If the peak airway pressure does not reach a predetermined value, the breathing circuit may have become disconnected. If the peak pressure is too high this may indicate obstruction of the airway or breathing circuit, or poor compliance. The patient may be at risk of barotrauma.Complications of ventilation

There are many complications of artificial ventilation. These include the following:

Risks associated with endotracheal intubation, including inability to intubate and dislodgement or blockage of the endotracheal tube, for example with secretions.

Risks associated with endotracheal intubation, including inability to intubate and dislodgement or blockage of the endotracheal tube, for example with secretions. Prolonged tracheal intubation may be associated with damage to the larynx (particularly the vocal cords) and trachea. Traditionally tracheostomy was performed at about 14 days but many units now perform percutaneous tracheostomy earlier. There is limited evidence for enhanced recovery with early tracheostomy in some patient groups (see Tracheostomy, p. 34).

Prolonged tracheal intubation may be associated with damage to the larynx (particularly the vocal cords) and trachea. Traditionally tracheostomy was performed at about 14 days but many units now perform percutaneous tracheostomy earlier. There is limited evidence for enhanced recovery with early tracheostomy in some patient groups (see Tracheostomy, p. 34). The drying effect of gases and impaired cough lead to retention of secretions and increases the likelihood of ventilator associated pneumonia.

The drying effect of gases and impaired cough lead to retention of secretions and increases the likelihood of ventilator associated pneumonia. Problems associated with the need for anaesthesia and / or sedation. These include the cardiovascular depressant effects of drugs, delayed gastric emptying, reduced mobility and delayed recovery. (See Sedation and analgesia, p. 34.)

Problems associated with the need for anaesthesia and / or sedation. These include the cardiovascular depressant effects of drugs, delayed gastric emptying, reduced mobility and delayed recovery. (See Sedation and analgesia, p. 34.) Haemodynamic effects of IPPV and PEEP include reduced venous return, reduced CO and reduced blood pressure. In turn, this reduces gut / renal blood flow and function.

Haemodynamic effects of IPPV and PEEP include reduced venous return, reduced CO and reduced blood pressure. In turn, this reduces gut / renal blood flow and function. Barotrauma. The effects of high pressures applied to the airway can result in damage to the delicate tissues of the lung. This may be manifest as pneumothorax, pneumopericardium, subcutaneous surgical emphysema, interstitial emphysema and even air embolism. Where possible peak pressure should not be allowed to exceed 35–40 cm H2O. If pressures above this are required, consider the underlying cause and the need for pressure controlled ventilation and ‘permissive hypercapnia’ (see ALI, p. 154).

Barotrauma. The effects of high pressures applied to the airway can result in damage to the delicate tissues of the lung. This may be manifest as pneumothorax, pneumopericardium, subcutaneous surgical emphysema, interstitial emphysema and even air embolism. Where possible peak pressure should not be allowed to exceed 35–40 cm H2O. If pressures above this are required, consider the underlying cause and the need for pressure controlled ventilation and ‘permissive hypercapnia’ (see ALI, p. 154). Volume trauma. Even at low pressures excessively large tidal volumes or unequal distribution of the tidal volume through the lung, so that some segments become overdistended, can result in volume trauma. The clinical manifestations of this are similar to barotrauma above, and include air leaks and cystic and emphysematous changes in the lung parenchyma.

Volume trauma. Even at low pressures excessively large tidal volumes or unequal distribution of the tidal volume through the lung, so that some segments become overdistended, can result in volume trauma. The clinical manifestations of this are similar to barotrauma above, and include air leaks and cystic and emphysematous changes in the lung parenchyma.COMMON PROBLEMS DURING ARTIFICIAL VENTILATION

Poor oxygenation

Consider disconnecting the patient from the ventilator and ‘hand bagging’. This effectively excludes a ventilator problem and provides 100% oxygen (see note below).

Consider disconnecting the patient from the ventilator and ‘hand bagging’. This effectively excludes a ventilator problem and provides 100% oxygen (see note below). Are both sides of the chest being ventilated equally? Check the position of the endotracheal tube. Is the tube too long or the tip abutting the carina on CXR?

Are both sides of the chest being ventilated equally? Check the position of the endotracheal tube. Is the tube too long or the tip abutting the carina on CXR? Is there any evidence of new collapse, pulmonary oedema, effusions or pneumothorax? Obtain a CXR (effusions / pneumothoraces may be better demonstrated on erect or semi-erect films). Treat any findings as appropriate.

Is there any evidence of new collapse, pulmonary oedema, effusions or pneumothorax? Obtain a CXR (effusions / pneumothoraces may be better demonstrated on erect or semi-erect films). Treat any findings as appropriate. Increase FiO2. Consider increasing PEEP, tidal volume and altering the I:E ratio (increase the inspiratory time). Consider pressure control ventilation, and alveolar recruitment manoeuvres.

Increase FiO2. Consider increasing PEEP, tidal volume and altering the I:E ratio (increase the inspiratory time). Consider pressure control ventilation, and alveolar recruitment manoeuvres. Consider permissive hypoxaemia where aggressive ventilation is more likely to result in harm than poor oxygenation. PaO2 above 8 kPa and SaO2 above 90% are considered safe.

Consider permissive hypoxaemia where aggressive ventilation is more likely to result in harm than poor oxygenation. PaO2 above 8 kPa and SaO2 above 90% are considered safe. Consider the need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) if ventilated for less than 5–7 days.

Consider the need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) if ventilated for less than 5–7 days.(See Ventilation strategy, p. 127, ALI, p. 154 and ECMO p. 158.)

Hypercapnia

Check ventilator settings, tidal volume and rate. Ensure that dead space in the ventilator circuit is minimal.

Check ventilator settings, tidal volume and rate. Ensure that dead space in the ventilator circuit is minimal. Check the endotracheal tube. Is there any evidence of obstruction (e.g. tube kinked or blocked with secretions)? Are both sides of the chest being ventilated equally? Are there any new clinical signs? Particularly, evidence of pneumothorax? Obtain a CXR if there is any doubt. Treat findings as appropriate.

Check the endotracheal tube. Is there any evidence of obstruction (e.g. tube kinked or blocked with secretions)? Are both sides of the chest being ventilated equally? Are there any new clinical signs? Particularly, evidence of pneumothorax? Obtain a CXR if there is any doubt. Treat findings as appropriate. Is there any evidencve of bronchospasm? Consider bronchodilators or in extreme cases volatile anaesthetic agents.

Is there any evidencve of bronchospasm? Consider bronchodilators or in extreme cases volatile anaesthetic agents. Consider permissive hypercapnia: sometimes an elevated PaCO2 is acceptable, either because lung pathophysiology makes reduction difficult / hazardous, or because the patient’s habitual PaCO2 is elevated.

Consider permissive hypercapnia: sometimes an elevated PaCO2 is acceptable, either because lung pathophysiology makes reduction difficult / hazardous, or because the patient’s habitual PaCO2 is elevated.Increased airway pressures

Increases in airway pressure generally indicate a significant problem and should be dealt with promptly, both to resolve the underlying cause and to prevent injury from barotrauma. Common causes of increased airway pressure are shown in Table 5.7.

| Endotracheal or tracheostomy tube | Kinked Patient biting endotracheal tube Obstructed with blood, secretions, etc. Too long (endobronchial) Misplaced outside trachea |

| Major airway | Obstructed with blood, secretions, etc. |

| Reduced compliance | Pulmonary collapse/consolidation/ALI Pneumothorax Pleural effusion Bronchospasm |

| Poor synchrony with ventilator | Inadequate sedation Inappropriate ventilator settings |

You should have a logical way of approaching this problem, such as:

Disconnect the patient from the ventilator and attempt to ventilate with 100% oxygen via a bag and mask.

Disconnect the patient from the ventilator and attempt to ventilate with 100% oxygen via a bag and mask. Check the patient. Is there partial or complete obstruction of the endotracheal tube or major airway? Suction may clear this. Consider bronchoscopy to clear major airways.

Check the patient. Is there partial or complete obstruction of the endotracheal tube or major airway? Suction may clear this. Consider bronchoscopy to clear major airways. If there is any doubt about the patency of the endotracheal or tracheostomy tube, remove / change it. Use a bougie or airway exchange catheter if difficulty in reintubation is anticipated.

If there is any doubt about the patency of the endotracheal or tracheostomy tube, remove / change it. Use a bougie or airway exchange catheter if difficulty in reintubation is anticipated. Are there any new clinical signs? Is there evidence of bronchospasm or pneumothorax? Treat any findings as appropriate. This may require physiotherapy and suction, improved humidification, nebulized bronchodilators.

Are there any new clinical signs? Is there evidence of bronchospasm or pneumothorax? Treat any findings as appropriate. This may require physiotherapy and suction, improved humidification, nebulized bronchodilators. If there is no evidence of an acute problem and airway pressures are rising due to reduced lung compliance or underlying pathophysiology, consider pressure control or alternative modes of ventilation.

If there is no evidence of an acute problem and airway pressures are rising due to reduced lung compliance or underlying pathophysiology, consider pressure control or alternative modes of ventilation.HIGH FREQUENCY MODES OF VENTILATION

In patients with low pulmonary compliance, conventional IPPV can result in high airway pressures, barotrauma and haemodynamic disturbance. High frequency ventilation has been tried as a means of reducing transpulmonary pressure, while providing adequate gas exchange. In most cases the tidal volume generated is less than anatomical dead space, and the exact mechanisms by which gas exchange is maintained are poorly understood. If you are considering these alternative modes of ventilation seek senior advice.

High frequency oscillation

A piston oscillates a diaphragm across the open airway resulting in a sinusoidal flow pattern with I:E ratio 1:1 (variable). This is unique in that both inspiration and expiration are active. Airway pressure oscillates around a slightly increased mean but the peak airway pressure is reduced. Increasing the mean airway pressure recruits more alveoli and improves oxygenation. CO2 clearance is controlled by altering the rate and amplitude of oscillation. Clearance of secretions is improved. This type of ventilation is well established in neonatal and paediatric intensive care. Oscillators capable of use in adults have recently become available and are becoming more established in adult practice. A typical approach to establishing high frequency oscillation is shown in Table 5.8. Always seek senior advice.

TABLE 5.8 Approach to establishing high frequency oscillation ventilation

| Mean airway pressure | 3–5 cm H2O above mean airway pressure on conventional ventilation |

| Amplitude | Increase sufficiently to generate visible and effective chest ‘wobble’ |

| Frequency | 6–8 Hz |

| Inspiratory time | 33% |

| FiO2 | 1.0 |

High frequency jet ventilation

This appears at present to be an increasingly obsolete mode of ventilation in critical care units. Pulses of gas are delivered at high pressure either through an attachment to the endotracheal tube or via a special endotracheal tube. The driving pressure and frequency can be varied. The jet of gas produced entrains air / oxygen from an open circuit (e.g. T-piece) and the tidal volume generated is generally of the order of 70–170 mL. Expiration is passive. Gas trapping may occur. The technique can be noisy and cumbersome. Humidification can be problematic. Typical settings are shown in Table 5.9.

| Driving pressure | 1.5–2.5 atmospheres (150–250 kPa) |

| Frequency | 60–200/min |

| I:E ratio | 1:1–1:1.5 |

There are two possible roles for jet ventilation:

Management of bronchopleural fistula. During conventional ventilation most of the tidal volume may be lost through the fistula, making effective ventilation of the patient impossible. Jet ventilation has been claimed to reduce transpulmonary pressures, thus reducing the leak. The evidence for this, however, is not strong; the main determinant seems to be the mean airway pressure, regardless of ventilator used.

Management of bronchopleural fistula. During conventional ventilation most of the tidal volume may be lost through the fistula, making effective ventilation of the patient impossible. Jet ventilation has been claimed to reduce transpulmonary pressures, thus reducing the leak. The evidence for this, however, is not strong; the main determinant seems to be the mean airway pressure, regardless of ventilator used.WEANING FROM ARTIFICIAL VENTILATION

As the patient’s condition improves, artificial ventilation can gradually be reduced until the patient is able to breathe unassisted. The decision to start weaning is largely one of clinical judgement, based on improving respiratory function and resolving underlying pathology. Studies have shown, however, that weaning is often delayed unnecessarily and there is evidence that the use of weaning protocols may reduce the time to extubation and reduce ICU stay. Typical criteria for successful weaning are shown in Table 5.10.

| Neuromuscular | Awake and co-operative Good muscle tone and function Intact bulbar function |

| Haemodynamic | No dysrhythmias Minimal inotrope requirements Optimal fluid balance |

| Respiratory | FiO2 < 0.5 (A–a) DO2 < 40 kPa Vital capacity > 10 mL/kg Tidal volume > 5 mL/kg Can generate negative inspiratory pressure > 20 cm H2O Good cough |

| Metabolic | Normal pH Normal electrolyte balance Adequate nutritional status Normal CO2 production Normal oxygen demands |

Some patients, particularly postoperative elective surgical cases, will tolerate weaning well and can be rapidly extubated. Others, particularly those who have been ventilated for some time, or who have significant lung damage or muscle wasting, may take longer and benefit from tracheostomy. There is no widely agreed policy on the best way to wean patients from ventilation. A typical approach is described below:

Gradually reduce the ventilator rate to allow the patient to take more breaths. Ensure adequate pressure support and PEEP to reduce the work of breathing.

Gradually reduce the ventilator rate to allow the patient to take more breaths. Ensure adequate pressure support and PEEP to reduce the work of breathing. When the patient is taking an adequate number of breaths with a good and sustained respiratory pattern, switch to CPAP with pressure support.

When the patient is taking an adequate number of breaths with a good and sustained respiratory pattern, switch to CPAP with pressure support. If the patient manages well, gradually reduce the level of pressure support further. When the pressure support is down to 10 cm H2O do not reduce it any further.

If the patient manages well, gradually reduce the level of pressure support further. When the pressure support is down to 10 cm H2O do not reduce it any further. Either extubate directly from CPAP and pressure support if the patient is likely to manage or switch to separate flow generator CPAP system and extubate later when it is anticipated that the patient will manage without any support (see Extubation, p. 403).

Either extubate directly from CPAP and pressure support if the patient is likely to manage or switch to separate flow generator CPAP system and extubate later when it is anticipated that the patient will manage without any support (see Extubation, p. 403).Weaning centres

There is interest in the concept of centralized weaning centres, where patients who no longer require full intensive care support, but still need respiratory support, might be managed with lower nursing and medical input. This model has been successfully adopted in several European countries. Patients are gradually weaned over time, either to full independence from ventilation or to partial independence (nocturnal ventilation). Some patients, typically those with severe chronic lung disease, chronic neuromuscular conditions and high cervical spine injuries, may require long-term ventilation.

AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

Airway obstruction is common in the immediate postoperative period while patients are in the recovery room and the effects of anaesthetic drugs wear off. Occasionally airway obstruction may persist or may be a potential risk following a particular surgical procedure. These patients will frequently be admitted to the ICU. (See Postoperative complications, p. 355.) Causes of airway obstruction are shown in Box 5.2.

Box 5.2 Causes of airway obstruction

Soft-tissue obstruction in upper airway

Bleeding/swelling/tumour/foreign body in upper airway

Vocal cord paralysis following damage to laryngeal nerve/hypocalcaemia

Bleeding/swelling/tumour/foreign body in lower airway

External compression of trachea, e.g. from bleeding/swelling in the neck

Collapse of trachea, e.g. tracheomalacia

Allergic reactions e.g. ACE inhibitors, anaphylaxis, angioneurotic oedema

Management

The management of any patient with airway obstruction is essentially the same, i.e. secure the airway by endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy as soon and as safely as possible. There are, however, a few points to bear in mind, depending on the situation and your own experience:

Simple manoeuvres such as extending the neck, jaw thrust and suctioning of the airway may improve the situation particularly in the obtunded patient.

Simple manoeuvres such as extending the neck, jaw thrust and suctioning of the airway may improve the situation particularly in the obtunded patient. Seek help from senior anaesthetist and ENT surgeon as appropriate. In these circumstances intubation / reintubation can often be difficult.

Seek help from senior anaesthetist and ENT surgeon as appropriate. In these circumstances intubation / reintubation can often be difficult.The definitive management is to secure the airway by tracheal intubation or tracheostomy. If time allows, this should be performed in theatre with surgeons scrubbed and prepared for emergency tracheostomy. Awake fibreoptic intubation, awake tracheostomy or gaseous anaesthetic induction with the patient breathing spontaneously may be appropriate, depending on the circumstances. It is beyond the scope of this text to cover these in detail. The usual problem at intubation is gross swelling and distortion of the tissues, which makes the laryngeal inlet difficult to visualize. Often the endotracheal tube has to be passed blindly through swollen tissues into the larynx. Occasionally obstruction proves to be lower down the airway and ventilation may be impossible even when the trachea is intubated.

Airway obstruction in the intubated patient

Ventilate with 100% oxygen if possible. If not, remove the endotracheal tube and manually ventilate the patient with a bag and mask before reintubation.

Ventilate with 100% oxygen if possible. If not, remove the endotracheal tube and manually ventilate the patient with a bag and mask before reintubation.Post-extubation stridor

Airway obstruction and stridor may occur following extubation. This may be as a result of underlying pathology but frequently results from laryngeal oedema, particularly in children whose airways are narrower. This may occasionally require reintubation. Two or three doses of dexamethasone (4 mg) given prior to extubation may reduce laryngeal swelling. Nebulized adrenaline and use of CPAP may be helpful. Where these measures prove ineffective, reintubation should not be delayed. A range of (small) endotracheal tubes and other emergency airway adjunct should be available. Seek senior help.

COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA

Typical pneumonia

The features of a ‘typical’ pneumonia include the following:

Chest X-rays show the appearances of consolidation, which may affect a single lobe, a whole lung or both lungs. The diagnosis is confirmed by raised WCC (predominantly neutrophils) and CRP, and by results of sputum and blood culture. The common causative organisms are shown in Table 5.11.

TABLE 5.11 Common causes of typical community-acquired pneumonia

| Lobar pneumonia | Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| Bronchopneumonia | Strep. pneumoniae Haemophilus influenzae Staphylococcus aureus Enterobacteria (less common unless risk factors/comorbidity) |

Atypical pneumonia

Non-respiratory symptoms may predominate. Fever, malaise, myalgia and arthralgia are common. Some may be associated with severe systemic illness.

Non-respiratory symptoms may predominate. Fever, malaise, myalgia and arthralgia are common. Some may be associated with severe systemic illness. Cough may only appear after a few days and is often non-productive. Sputum that is produced is clear and often negative on Gram stain and culture.

Cough may only appear after a few days and is often non-productive. Sputum that is produced is clear and often negative on Gram stain and culture. There may be disparity between the clinical signs on chest examination and the CXR with minimal signs on examination of the chest, whereas CXR shows widespread patchy consolidation with interstitial and alveolar infiltrates.

There may be disparity between the clinical signs on chest examination and the CXR with minimal signs on examination of the chest, whereas CXR shows widespread patchy consolidation with interstitial and alveolar infiltrates.Causes of atypical community-acquired pneumonia are shown in Table 5.12.

| Viral | Influenza A, B Parainfluenza Respiratory syncytial virus |

| Bacterial | Legionella pneumophila Coxiella burnetii Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| Chlamydia | Chlamydia psittaci |

| Mycoplasma | Mycoplasma pneumoniae |

HOSPITAL-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA

Hospital-acquired pneumonias are a common cause of morbidity in hospitalized patients. Up to 20% of all mechanically ventilated patients develop ventilator-associated pneumonia and the incidence is higher in the immunocompromised patient. Gram-negative organisms and Staphylococcus aureus are particularly common. A number of factors may increase the risk of pneumonia in critically ill patients, by impairing host defence mechanisms and increasing colonization of the upper airway. These are summarized in Table 5.13.

| Critical illness | Impaired host defences and immune systems |

| Sedation | Impaired mucus transport and cough mechanisms |

| Endotracheal and tracheostomy tubes | Bypass normal host defence mechanisms Increased colonization of upper airways Laryngeal incompetence increases risk of aspiration |

| Antacids | Reduce gastric acidity, allow increased colonization of stomach with lower GI flora |

| Nasogastric tubes | Provide route for increased colonization of upper airway with lower GI flora from stomach |

| Broad-spectrum antibiotics | Destroy normal commensal flora and promote colonization with pathogenic microorganisms |

Hygiene measures

Ensure adequate hygiene procedures and aseptic technique at all times. Suction the oropharynx regularly to prevent secretions pooling above the larynx and nurse patients in a semi-recumbent position to reduce the risk of passive aspiration. Ensure adequate humidification of inspired gases and regular physiotherapy and tracheal suction. Use closed suction devices or wear sterile gloves when suctioning the airway. The use of chlorhexidine mouthwashes has been advocated.

Selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD)

SDD is a method of reducing colonization of the upper airways by using oral, non-absorbable antibiotics in an attempt to reduce the bacterial load in the GI tract. There is some evidence that this is effective at reducing nosocomial infection; however, at the current time SDD is not in widespread use in the UK because of concerns that it may drive the emergence of multi-drug resistant bacteria and promote MRSA infection. Further studies are ongoing.

PNEUMONIA IN IMMUNOCOMPROMISED PATIENTS

(See also The immunocompromised patient, p. 226.)

Patients who are immunocompromised for any reason may present with pneumonia. In addition to the typical and atypical conditions already described, a number of other opportunistic pathogens typically infect these patients. These are shown in Box 5.3.

Fungal pneumonia

Colonization of the pharynx, GIT, perineum, wounds and skin folds is common and rarely requires treatment. Significant fungal infections may occur after prolonged treatment with antibiotics and particularly in immunocompromised patients. Infection is suggested by significant growth in sputum, tracheal aspirates, BAL fluids and blood cultures. In addition there may be rising serum antibody titres to Candida or the presence of Aspergillus antigens. Fungal infection, particularly fungal septicaemia, is associated with a high mortality.

MANAGEMENT OF PNEUMONIA

All patients with pneumonia requiring admission to intensive care should have full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, C-reactive protein (CRP) and CXR performed. Possible microbiological investigations are summarized in Table 5.14. Not all patients require the full spectrum of investigations: these should be guided by severity, risk factors and response to treatment.

| Sample | Investigation |

|---|---|

| Sputum/tracheal aspirate | Microscopy, culture and sensitivity |

| BAL | M,C & S (including AAFB) Legionella immunofluorescence Viruses Fungi Pneumocystis |

| Nasopharyngeal aspirate/pernasal swab | Viruses |

| Blood | Blood culture Serology (acute and convalescent samples) Viral titres Complement fixation (Mycoplasma, Chlamydia) |

| Urine | Legionella immunofluorescence |

| Pleural fluid | M,C & S |

The treatment of any pneumonia is twofold:

Supportive therapy including humidified oxygen and ventilation as necessary. Regular physiotherapy and tracheal suction to aid clearance of secretions.

Supportive therapy including humidified oxygen and ventilation as necessary. Regular physiotherapy and tracheal suction to aid clearance of secretions. Antibiotic therapy. Choice will depend upon the clinical picture and the nature of the infecting organism. Wherever possible, microbiological specimens should be obtained prior to the commencement of antibiotics.

Antibiotic therapy. Choice will depend upon the clinical picture and the nature of the infecting organism. Wherever possible, microbiological specimens should be obtained prior to the commencement of antibiotics.Hospital-acquired pneumonia

The management of hospital acquired pneumonia is similar to the management of any other pneumonia (see above). Ideally antibiotics should be used only for microbiologically proven infection. If, however, the patient’s condition dictates blind antibiotic therapy, ensure microbiological specimens are obtained before commencing treatment. Antibiotic therapy needs to be guided by the likely source of the pathogens and by the local pattern of microbial antibiotic resistance. Seek microbiological advice. (See Empirical antibiotic therapy, p. 336, MRSA, p. 336 and VRE, p. 336.)

Pneumonia in immunocompromised patients

ASPIRATION PNEUMONITIS

Suction the trachea to remove debris. If possible suction should be applied before any form of positive pressure ventilation.

Suction the trachea to remove debris. If possible suction should be applied before any form of positive pressure ventilation. Avoid antibiotics unless there is evidence of infection. If necessary, antibiotic therapy should cover the normal respiratory pathogens plus Gram-negatives and anaerobes. A combination of broad-spectrum cephalosporin and metronidazole is appropriate initially. Further treatment should be guided by the results of microbiological investigation.

Avoid antibiotics unless there is evidence of infection. If necessary, antibiotic therapy should cover the normal respiratory pathogens plus Gram-negatives and anaerobes. A combination of broad-spectrum cephalosporin and metronidazole is appropriate initially. Further treatment should be guided by the results of microbiological investigation.ASTHMA

Asthma occurs principally in young people and the incidence of this potentially life-threatening condition is increasing. Asthma involves increased airway reactivity, often triggered by an environmental stimulus, or following infection. An inflammatory process results in narrowing of small airways, mucus plugging, expiratory wheeze and air trapping. Severe asthma is a medical emergency. It may be rapidly progressive and clinical signs may be misleading. The clinical signs of severe asthma are shown in Box 5.4.

Box 5.4 Clinical signs of severe asthma

| Severe asthma | Life-threatening asthma |

| Inability to talk in sentences | Exhaustion, confusion, reduced conscious level |

| Peak flow < 50% predicted/best | Peak flow < 33% predicted/best |

| Respiratory rate > 25/min | Feeble respiratory effort or ‘silent’ chest |

| Pulse rate > 110/min; pulsus paradoxus | Bradycardia or hypotension: SaO2 < 92% PaO2 < 8 kPa PaCO2 > 5 kPa pH < 7.3 |

Management

Give nebulized β-agonists (salbutamol 2.5–5 mg neb.) and anticholinergics (ipratropium bromide 0.5 mg neb.). Repeat as frequently as required. Ensure nebulizers are given in oxygen not air.

Give nebulized β-agonists (salbutamol 2.5–5 mg neb.) and anticholinergics (ipratropium bromide 0.5 mg neb.). Repeat as frequently as required. Ensure nebulizers are given in oxygen not air. Give i.v. corticosteroids to suppress the inflammatory response. Hydrocortisone 200 mg bolus then 100 mg 6-hourly.

Give i.v. corticosteroids to suppress the inflammatory response. Hydrocortisone 200 mg bolus then 100 mg 6-hourly. There is no role for antibiotics unless there is clear evidence of a precipitating bacterial infection.

There is no role for antibiotics unless there is clear evidence of a precipitating bacterial infection. If there is no improvement, commence i.v. β-agonist, either salbutamol 4 μg / kg loading dose over 10 min followed by infusion 5 μg / min or aminophylline 5 mg / kg loading dose over 10 min followed by infusion 0.5 mg kg h.

If there is no improvement, commence i.v. β-agonist, either salbutamol 4 μg / kg loading dose over 10 min followed by infusion 5 μg / min or aminophylline 5 mg / kg loading dose over 10 min followed by infusion 0.5 mg kg h. If there is no improvement or the patient’s condition is life-threatening, consider need for ventilation. Indications for ventilation are shown in Box 5.5.

If there is no improvement or the patient’s condition is life-threatening, consider need for ventilation. Indications for ventilation are shown in Box 5.5.Following intubation ensure adequate analgesia and sedation. The presence of an endotracheal tube in the larynx of an inadequately sedated asthmatic is a potent source of irritation and continued bronchoconstriction. Standard sedative regimens are generally sufficient. There may be a role for ketamine infusion both as a sedative agent and as a bronchodilator in refractory bronchospasm. Muscle relaxation may be required initially in severe cases. Avoid agents likely to release histamine, such as atracurium or mivacurium. Cisatracurium, vecuronium or pancuronium are less likely to cause direct release histamine.

If severe hyperinflation becomes a problem it may be necessary to disconnect the patient from the ventilator and manually ventilate with a long expiratory time. Manual compression of the chest wall has been used to expel trapped air and improve respiratory mechanics. Volatile anaesthetic agents may be useful in severe bronchospasm. These can be either given through an anaesthetic machine but the attached ventilators are often incapable of ventilating such patients. There are specialized pumped injector delivery systems for volatile agents into ICU ventilator circuits. Occasional patients can be managed with ECMO or related technology, though this is likely to require transfer to a specialist centre, which may be problematic or impossible in the patient with severe acute bronchospasm. Simple systems for extracorporeal CO2 removal are available (e.g. Novalung®) that can be used outside specialist centres to reduce a high PaCO2.

CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE

Management

Due to the effects of long-term compensatory mechanisms, these patients often tolerate markedly deranged blood gases (hypoxia and hypercapnia) very well. Therefore, it is the clinical condition of the patient rather than blood gases that determines the need for ventilatory support. Assess the patient clinically. If able to talk, and not distressed, the patient is unlikely to need immediate ventilation, regardless of the blood gas picture.

Due to the effects of long-term compensatory mechanisms, these patients often tolerate markedly deranged blood gases (hypoxia and hypercapnia) very well. Therefore, it is the clinical condition of the patient rather than blood gases that determines the need for ventilatory support. Assess the patient clinically. If able to talk, and not distressed, the patient is unlikely to need immediate ventilation, regardless of the blood gas picture. Correct hypoxia by incremental increase in FiO2. Aim to achieve PaO2 7–8 kPa, SaO2 ≥ 90% or that which is normal for the patient.

Correct hypoxia by incremental increase in FiO2. Aim to achieve PaO2 7–8 kPa, SaO2 ≥ 90% or that which is normal for the patient. In some patients with COPD and type 2 respiratory failure, chronic hypercapnia results in loss of the normal ventilatory responsiveness to CO2. In these patients hypoxia is the main stimulus to respiration. High concentrations of inspired oxygen can result in the loss of the stimulus to respiration and precipitate respiratory arrest. Look at the bicarbonate concentration on the blood gas. If this is normal, or only slightly raised (<30 mmol / L), chronic CO2 retention is unlikely to exist and the patient should not be dependent on hypoxic drive. Increase the inspired oxygen concentration as necessary and repeat the blood gases after 30 min.In cases where the patient is dependent on hypoxic drive, the PaCO2 may rise and the need for assisted ventilation may be precipitated earlier.

In some patients with COPD and type 2 respiratory failure, chronic hypercapnia results in loss of the normal ventilatory responsiveness to CO2. In these patients hypoxia is the main stimulus to respiration. High concentrations of inspired oxygen can result in the loss of the stimulus to respiration and precipitate respiratory arrest. Look at the bicarbonate concentration on the blood gas. If this is normal, or only slightly raised (<30 mmol / L), chronic CO2 retention is unlikely to exist and the patient should not be dependent on hypoxic drive. Increase the inspired oxygen concentration as necessary and repeat the blood gases after 30 min.In cases where the patient is dependent on hypoxic drive, the PaCO2 may rise and the need for assisted ventilation may be precipitated earlier. Avoid respiratory stimulants such as doxapram. These generally do not help and can result in patients becoming exhausted and requiring ventilation. Consider use of CPAP or non-invasive ventilation.

Avoid respiratory stimulants such as doxapram. These generally do not help and can result in patients becoming exhausted and requiring ventilation. Consider use of CPAP or non-invasive ventilation. Give nebulized β-agonists (salbutamol 2.5–5 mg neb.) and anticholinergics (ipratropium bromide 0.5 mg neb.). Repeat as frequently as required. Ensure nebulizers are given in oxygen not air.

Give nebulized β-agonists (salbutamol 2.5–5 mg neb.) and anticholinergics (ipratropium bromide 0.5 mg neb.). Repeat as frequently as required. Ensure nebulizers are given in oxygen not air. Give i.v. corticosteroids (hydrocortisone 200 mg bolus then 100 mg 6-hourly) to suppress the inflammatory response.

Give i.v. corticosteroids (hydrocortisone 200 mg bolus then 100 mg 6-hourly) to suppress the inflammatory response. If there is no improvement, commence i.v. β-agonist, either salbutamol 4 μg/kg loading dose over 10 min followed by infusion 5 μg/min or aminophylline 5 mg/kg loading dose over 10 min followed by infusion 0.5 mg/ kg/ h.

If there is no improvement, commence i.v. β-agonist, either salbutamol 4 μg/kg loading dose over 10 min followed by infusion 5 μg/min or aminophylline 5 mg/kg loading dose over 10 min followed by infusion 0.5 mg/ kg/ h.Intensive care management

Where possible transfer the patient directly to the ICU for intubation and ventilation rather than attempting this on the ward.

Where possible transfer the patient directly to the ICU for intubation and ventilation rather than attempting this on the ward. If the patient’s condition allows, site an arterial line and institute arterial pressure monitoring before induction.

If the patient’s condition allows, site an arterial line and institute arterial pressure monitoring before induction. Consider giving a fluid bolus (e.g. 500 mL of colloid) prior to induction. Have adrenaline (epinephrine) available for resuscitation.

Consider giving a fluid bolus (e.g. 500 mL of colloid) prior to induction. Have adrenaline (epinephrine) available for resuscitation. After securing the airway, institute IPPV. SIMV mode is usually adequate. Avoid hyperventilation. Rapid lowering of the PaCO2 may further reduce sympathetic drive and lower the blood pressure.

After securing the airway, institute IPPV. SIMV mode is usually adequate. Avoid hyperventilation. Rapid lowering of the PaCO2 may further reduce sympathetic drive and lower the blood pressure. Continue antibiotic therapy according to local protocol. (See Pneumonia, p. 141, and Empirical antibiotic therapy, p. 336.)

Continue antibiotic therapy according to local protocol. (See Pneumonia, p. 141, and Empirical antibiotic therapy, p. 336.)ACUTE LUNG INJURY

The clinical signs of acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are those of increasing respiratory distress, with associated tachycardia, tachypnoea and onset of cyanosis. Blood gases indicate severe hypoxaemia. The CXR shows acute bilateral interstitial and alveolar shadowing. The non-cardiogenic nature of the alveolar oedema can be confirmed by pulmonary artery catheterization (PAOP < 18 mmHg, CI > 2 L / min / m3) or echocardiography and infective processes excluded by BAL.

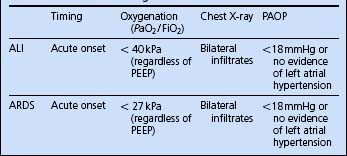

The principal diagnostic criterion used to distinguish ALI and ARDS is the degree of hypoxaemia, as shown in Table 5.15.

Pathophysiology

A large number of conditions have been associated with the onset of ALI / ARDS, as indicated in Box 5.6.

| Physical | Infective | Inflammatory/immune |

|---|---|---|

| Trauma | Pneumonia | Blood transfusion |

| Acid aspiration | Septicaemia | Cardiopulmonary bypass |

| Fat embolism | Pancreatitis | Anaphylaxis |

| Smoke inhalation | ||

It is clear that an ALI can develop in response to a wide range of insults. The exact processes by which this occurs are not fully understood. It is characterized by proliferation of inflammatory cells, increased permeability of the alveolar capillaries and leak of proteinaceous fluid into the alveoli (so-called ‘non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema’). This protein-rich material precipitates, forming hyaline membranes. In survivors, the acute inflammatory process gradually subsides and healing occurs. This may result in widespread interstitial lung fibrosis. Not all patients who have ALI go on to develop severe ARDS. There is a spectrum of disease ranging from mild to severe.

Although used primarily as a research tool, a scoring system for grading the severity of ALI / ARDS has been devised. This is shown in Table 5.16.

| Component | Assign value |

|---|---|

| Chest X-ray appearance | |

| No alveolar consolidation Alveolar consolidation in 1 quadrant Alveolar consolidation in 2 quadrants Alveolar consolidation in 3 quadrants Alveolar consolidation all 4 quadrants |

0 1 2 3 4 |

| Hypoxaemia score (PaO2/FiO2 mmHg)* | |

| >300 225–299 175–224 100–174 <100 |

0 1 2 3 4 |

| Compliance (mL/ cmH2O) | |

| >80 >60 >40 >20 <20 |

0 1 2 3 4 |

| PEEP (cm H2O) | |

| <5 6–8 9–11 12–14 >15 |

0 1 2 3 4 |

| Score generated by dividing sum of component values by number of components used | |

| Score = 0 Score < 2.5 Score > 2.5 |

No lung injury Mild to moderate lung injury Severe lung injury (ARDS) |

Source: Murray JF, Matthay MA, Luce JM, Flick MR 1989 American Review of Respiratory Disease139: 1065.

Management

Severe ARDS is associated with a high mortality ranging from approximately 25 to 80% in different series. The best outcomes have been reported from centres using strict protocols for management. In general:

Institute invasive cardiovascular monitoring (arterial line, CVP, pulmonary artery catheter or equivalent) and use inotropes / vasopressors as appropriate to optimize CO, perfusion pressure and oxygen delivery.

Institute invasive cardiovascular monitoring (arterial line, CVP, pulmonary artery catheter or equivalent) and use inotropes / vasopressors as appropriate to optimize CO, perfusion pressure and oxygen delivery. Artificial ventilation is usually necessary. Reduced pulmonary compliance results in high inflation pressures, which are associated with increased risks of barotrauma. Current ventilatory strategies are intended to limit ventilator-associated lung damage while providing for alveolar recruitment. Pressure control ventilation, with longer inspiratory times (reversed I:E ratio) may be used to limit peak airway pressure. Tidal volumes should not exceed 6 mL / kg. Increased levels of PEEP are used to promote alveolar recruitment and improve oxygenation (see Ventilation strategy, p. 127).

Artificial ventilation is usually necessary. Reduced pulmonary compliance results in high inflation pressures, which are associated with increased risks of barotrauma. Current ventilatory strategies are intended to limit ventilator-associated lung damage while providing for alveolar recruitment. Pressure control ventilation, with longer inspiratory times (reversed I:E ratio) may be used to limit peak airway pressure. Tidal volumes should not exceed 6 mL / kg. Increased levels of PEEP are used to promote alveolar recruitment and improve oxygenation (see Ventilation strategy, p. 127). The FiO2 should be kept to the minimum necessary to maintain acceptable oxygenation (PaO2 7–8 kPa, SaO2 ≥ 90%) in order to reduce lung damage associated with oxygen toxicity. Moderate levels of hypercapnia may be tolerated (permissive hypercapnia) if excessive ventilatory pressures would otherwise be required.

The FiO2 should be kept to the minimum necessary to maintain acceptable oxygenation (PaO2 7–8 kPa, SaO2 ≥ 90%) in order to reduce lung damage associated with oxygen toxicity. Moderate levels of hypercapnia may be tolerated (permissive hypercapnia) if excessive ventilatory pressures would otherwise be required. Although in ARDS pulmonary oedema is classically thought of as non-cardiogenic, these patients often have multiple organ failure. It is estimated that 25% may develop myocardial failure, and fluid overload is common. Diuretics may be given to ‘dry’ the patient and may help to reduce the extent of pulmonary oedema.

Although in ARDS pulmonary oedema is classically thought of as non-cardiogenic, these patients often have multiple organ failure. It is estimated that 25% may develop myocardial failure, and fluid overload is common. Diuretics may be given to ‘dry’ the patient and may help to reduce the extent of pulmonary oedema.Nitric oxide

Nitric oxide is a naturally occurring vasodilator produced by the endothelium of blood vessels. If added to the inspiratory gases in concentrations of 5–20 v.p.m., it results in pulmonary vasodilatation in those areas of the lung that are well ventilated. Blood is diverted away from poorly ventilated areas. Ventilation–perfusion mismatch is reduced and there is an improvement in oxygenation. At the same time pulmonary hypertension and the risk of right heart failure is reduced. Nitric oxide has a short half-life when inhaled and is generally safe for the patient. It is, however, a toxic gas, and should only be used according to the protocols established in your unit. Although nitric oxide may produce an improvement in oxygenation and therefore allow reduced FiO2 and airway pressures, there is little evidence that it improves outcome.

ECMO

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is a technique that allows oxygenation to be maintained while the lungs recover. The benefits are well recognized in neonatal and paediatric practice, but are less well established in adult practice, although a recent study in adults has reported favourable results [Conventional ventilation or ECMO for Severe Adult Respiratory Failure (CESAR) Trial. www.cesar-trial.org]. In the UK, ECMO is only provided in a limited number of centres and the transfer of patients with severe hypoxaemia is hazardous. Evidence suggests that to be of benefit it should be started within 5–7 days of artificial ventilation being commenced.

CHEST X-RAY INTERPRETATION

The combination of tracheal intubation or tracheostomy and IPPV makes interpretation of classic respiratory signs in the noisy environment of the ICU very difficult. The CXR therefore assumes additional importance when evaluating the patient’s condition.

Check name, date and orientation of film. The normal CXR orientation is posteroanterior (PA). That is, the X-rays are passed through the patient from behind towards the film, which is in front. Films taken in intensive care are generally anteroposterior (AP). This alters the magnification of structures.

Check name, date and orientation of film. The normal CXR orientation is posteroanterior (PA). That is, the X-rays are passed through the patient from behind towards the film, which is in front. Films taken in intensive care are generally anteroposterior (AP). This alters the magnification of structures. Central venous catheters. Check intrathoracic placement with the tip positioned in a site consistent with the superior vena cava, above the pericardial reflection (see p. 376).

Central venous catheters. Check intrathoracic placement with the tip positioned in a site consistent with the superior vena cava, above the pericardial reflection (see p. 376). Pulmonary artery catheter. Check tip lying in the pulmonary artery, preferably on the right side and not too distal (within 2 cm of edge of the spinal column).

Pulmonary artery catheter. Check tip lying in the pulmonary artery, preferably on the right side and not too distal (within 2 cm of edge of the spinal column).A number of CXR patterns are common in intensive care.

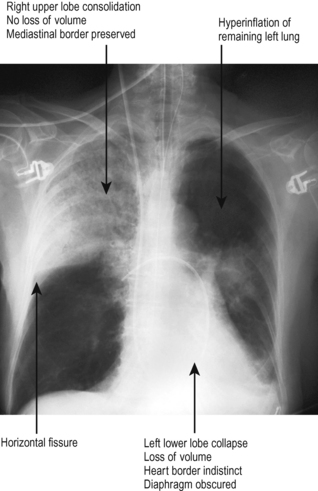

Consolidation and collapse

These terms are often used incorrectly and even interchangeably. The X-ray appearances of consolidation and collapse are, however, quite distinct (Fig. 5.4).

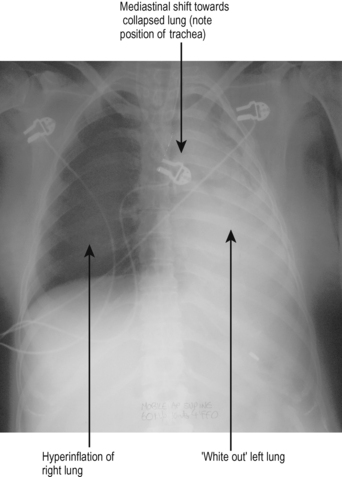

Collapse of a lung

An extreme example of collapse is collapse of an entire lung. In intubated and ventilated patients this may occur as a result of obstruction of the bronchus (e.g. by mucus plugging) or following endobronchial intubation. The anatomy of the bronchial tree is such that endotracheal tubes are more likely to pass down the right main bronchus than the left. This commonly leads to collapse of the left lung, the typical appearances of which are shown in Fig. 5.5.

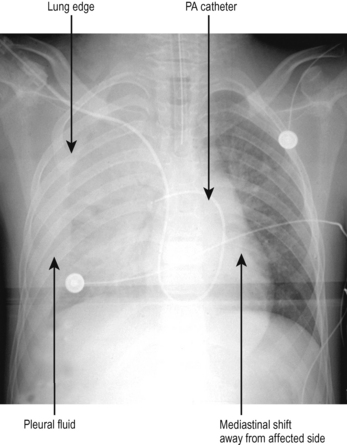

Pleural effusion / haemothorax

The classic feature of a pleural effusion in an upright patient is that of uniform opacification in the pleural space, typically obscuring the costodiaphragmatic recess, with an obvious meniscus or fluid level. In critically ill patients, CXRs are generally taken with the patient supine, often in the presence of positive pressure ventilation or CPAP. Therefore the classic appearance of pleural effusion may be missed. The only evidence of a small or moderate pleural effusion may be a general white haze to the whole lung field (imagine the fluid lying posteriorly in the pleural space). Larger effusions may have classic features or may present with a ‘white-out’ of that side, with shift of mediastinal structures towards the other side (Fig. 5.6).

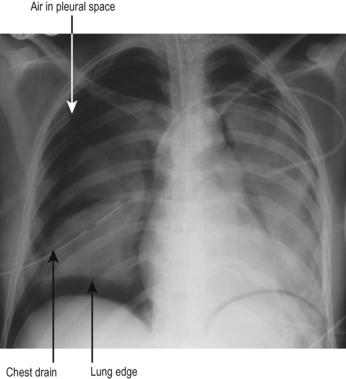

Pneumothorax

Pneumothorax should be suspected in any patient who deteriorates while on a ventilator, particularly if there is associated trauma or recent insertion of a tracheostomy, central line or other practical procedure in the chest or neck. The typical appearances are that of a visible lung edge and translucent free air in the pleural space, as shown in Fig. 5.7.

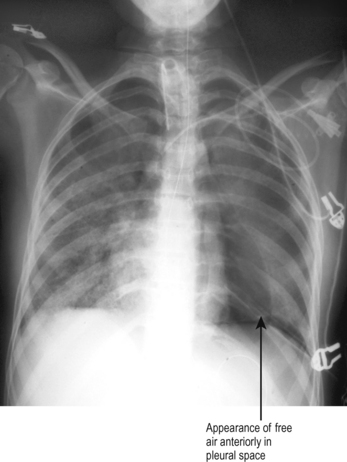

The appearance may not, however, always be so obvious. In the critically ill supine patient with a small pneumothorax, free air may lie anteriorly over the lung and there may be no visible lung edge on CXR. (This is analogous to small pleural effusions lying posteriorly.) The only evidence may be that of an increased translucency (blackness) anteriorly, as shown in Fig. 5.8. If in doubt a lateral CXR or CT scan may help.

Surgical emphysema and mediastinal air

Air may leak outside the pleural cavity, presenting as surgical emphysema and / or as mediastinal air on CXR. Surgical emphysema typically develops in the face, neck, mediastinum, pericardium, abdomen and scrotum and has a ‘tissue paper’ feel on palpation. It is visible on X-ray as black air shadows in the soft tissues of the upper body and chest wall, often outlining the pectoral muscles. Mediastinal air is visible on CXR as black translucent areas usually outlining the mediastinal shadows.

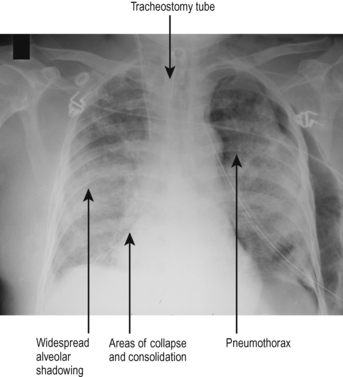

ALI / ARDS

The CXR appearances of ALI and ARDS are not specific. The common response to lung injury is leaking of capillaries, accumulation of alveolar fluid and subsequent development of areas of collapse and consolidation. The features are therefore a combination of those described above. A typical example is shown in Fig. 5.9.

When looking at a compensated acid / base disturbance remember that the compensatory mechanisms are never sufficient to completely return the pH to normal. Therefore if the pH is acidotic ( < 7.4) the underlying problem is acidosis, if the pH is alkalotic ( > 7.4) the underlying problem is alkalosis.

When looking at a compensated acid / base disturbance remember that the compensatory mechanisms are never sufficient to completely return the pH to normal. Therefore if the pH is acidotic ( < 7.4) the underlying problem is acidosis, if the pH is alkalotic ( > 7.4) the underlying problem is alkalosis.

Sudden loss of ETCO2 indicates either failure of ventilation (e.g. obstruction of the endotracheal tube / disconnection of the breathing circuit) or loss of cardiac output.

Sudden loss of ETCO2 indicates either failure of ventilation (e.g. obstruction of the endotracheal tube / disconnection of the breathing circuit) or loss of cardiac output.

Endotracheal tube problems are more common than acute severe bronchospasm, and do not respond to bronchodilators. A blocked, kinked, malpositioned or obstructed endotracheal tube can be rapidly fatal. There is a great wisdom in the old saying ‘If in doubt, take it out’.

Endotracheal tube problems are more common than acute severe bronchospasm, and do not respond to bronchodilators. A blocked, kinked, malpositioned or obstructed endotracheal tube can be rapidly fatal. There is a great wisdom in the old saying ‘If in doubt, take it out’.

In any of the above scenarios it may be helpful to disconnect the ventilator and ventilate the patient by hand in order to exclude ventilator problems, improve oxygenation or assess compliance. The principle advantage is application of 100% oxygen and increased mean airway pressure. The disadvantage is even short periods of disconnection can lead to atelectasis / collapse (loss of PEEP). Only disconnect the patient if really necessary.

In any of the above scenarios it may be helpful to disconnect the ventilator and ventilate the patient by hand in order to exclude ventilator problems, improve oxygenation or assess compliance. The principle advantage is application of 100% oxygen and increased mean airway pressure. The disadvantage is even short periods of disconnection can lead to atelectasis / collapse (loss of PEEP). Only disconnect the patient if really necessary.

Helium–oxygen mix is less dense than air and may reduce the work of breathing in patients with airway obstruction. Heliox® is a commercially available mixture containing 79% helium / 21% oxygen. The low fractional inspired oxygen limits its usefulness.

Helium–oxygen mix is less dense than air and may reduce the work of breathing in patients with airway obstruction. Heliox® is a commercially available mixture containing 79% helium / 21% oxygen. The low fractional inspired oxygen limits its usefulness. Seek urgent senior help. Do not delay getting help because of apparently good oxygenation. Hypoxia on the pulse oximeter / arterial blood gases is likely to be a very late sign.

Seek urgent senior help. Do not delay getting help because of apparently good oxygenation. Hypoxia on the pulse oximeter / arterial blood gases is likely to be a very late sign.