Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection (Bronchiolitis or Pneumonitis)

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection.

• Describe the causes of respiratory syncytial virus infection.

• List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with respiratory syncytial virus infection.

• Describe the general management of respiratory syncytial virus infection.

• Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAP presented in the case study.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

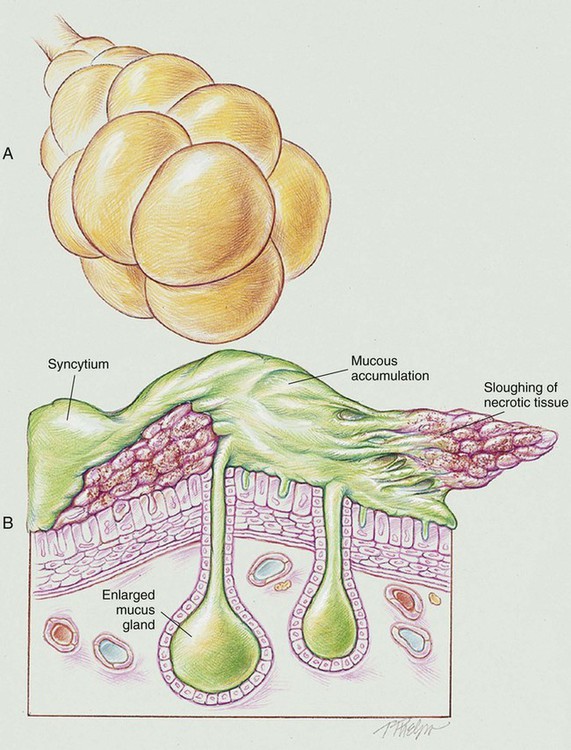

RSV infection causes peribronchiolar mononuclear infiltration and necrosis of the epithelium of the small airways. This condition leads to edema of the small airways and increased production of mucus. As the condition worsens, the epithelium of the small airways becomes necrotic and proliferates into the airway lumen. The combination of sloughing necrotic tissue, airway edema, and accumulation of mucus leads to (1) a decreased airway lumen, (2) a partially obstructed airway, or (3) a completely obstructed airway. Partial airway obstruction leads to alveolar hyperinflation as a result of a “ball-valve” mechanism (see Figure 36-1). Complete airway obstruction leads to alveolar collapse or atelectasis. Pneumonic consolidation is common. RSV is also referred to as bronchiolitis or pneumonitis.

The following major pathologic or structural changes are associated with RSV infection:

Etiology and Epidemiology

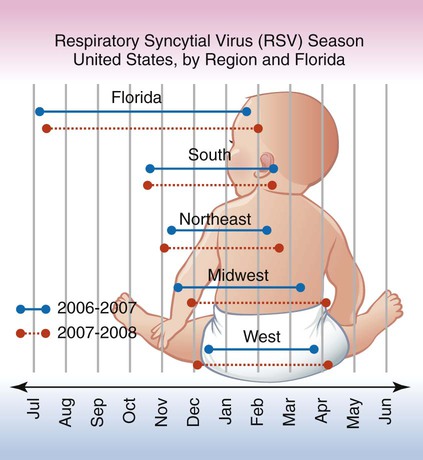

Although the outbreak of RSV cases varies by location each year, the number of RSV cases typically increases during the fall, winter, and early spring months. It is not fully known why RSV outbreaks occur in certain regions more than in others, but temperature, climate, and humidity appear to play a role. Figure 36-2 shows the typical RSV season in the United States by region and in Florida according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

General Management of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection (Bronchiolitis, Pneumonitis)

Respiratory Care Treatment Protocols

Oxygen Therapy Protocol

Oxygen therapy is used to treat hypoxemia, decrease the work of breathing, and decrease myocardial work. The hypoxemia that develops in RSV most commonly is caused by the excessive airway fluid, atelectasis, and consolidation associated with the disorder. Hypoxemia caused by capillary shunting is often partially refractory to oxygen therapy (see Oxygen Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-1).

CASE STUDY

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Infection

Admitting History and Physical Examination

A premature baby boy was born in mid-November at 31 weeks’ gestation. He weighed 1300 g at birth and immediately demonstrated respiratory distress that rapidly progressed into respiratory distress syndrome (RDS; see Chapter 34). During the first hour after delivery, the baby was intubated, placed on a mechanical ventilator, and given a dose of pulmonary surfactant. An umbilical artery line was inserted, and antibiotics were given for several days. Over the next 10 days, the baby was slowly weaned off the ventilator and started on oral feedings. Both the umbilical artery and intravenous (IV) lines were discontinued. Over the next week, the baby gained weight and appeared to be doing well.

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

O Apnea. Positive RSV smear. Vital signs: HR 165 bpm, BP 85/55, RR 65, T 37° C. Nasal flaring, intercostal retractions, and cyanosis. Wheezing and rhonchi. CXR: Atelectasis. Spo2 on Fio2 0.40: 88%. Ventilator settings: IMV rate 15, PIP +20, PEEP +4, flow 6 L/min.

P Continue Mechanical Ventilation Protocol. Begin Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol (CPT and suction prn). Begin Aerosolized Medication Therapy Protocol (0.25 mg albuterol per kg with 2 mL normal saline q3h, in-line with the ventilator). Oxygen therapy per Mechanical Ventilation Protocol. Continue to monitor closely. Obtain ABGs via capillary heel stick and reevaluate.

Discussion

In most cases, however, the anatomic alterations of the lung and the clinical manifestations that ensue can be effectively treated by good respiratory therapy (i.e., appropriate oxygen therapy, bronchopulmonary hygiene therapy, and bronchodilator therapy). For example, the implementation of the Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol to offset the Excessive Bronchial Secretions (see Figure 9-12) and the administration of the Aerosolized Medication Therapy Protocol (albuterol) to offset the Bronchospasm (see Figure 9-11) demonstrated in this case were clearly justified.

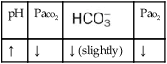

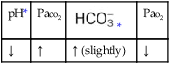

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

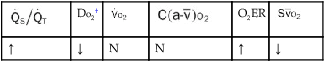

, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;

, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;  , pulmonary shunt fraction;

, pulmonary shunt fraction;  , mixed venous oxygen saturation;

, mixed venous oxygen saturation;  , oxygen consumption.

, oxygen consumption.