35 Respiratory infections

Upper respiratory tract infections

Colds and flu

Viral URTIs causing coryzal symptoms, rhinitis, pharyngitis and laryngitis, and associated with varying degrees of systemic symptoms, are extremely common. These infections are usually caused by viruses from the rhinovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus and adenovirus families, although new viruses continue to be identified. For instance, in 2001, a novel respiratory pathogen was described that has become known as human metapneumovirus (hMPV). This causes a spectrum of respiratory illnesses particularly in young children, the elderly and the immunocompromised (Van Den Hoogen et al., 2001).

Influenza

National guidelines for the UK recommend NAIs should only be used when influenza is circulating in the community (which is carefully defined), and in patients who are both at risk of developing complications and can commence treatment within a defined time window of onset or exposure (NICE, 2008, 2009). Individuals at risk and eligible for treatment include those:

Pandemics (or global epidemics) of influenza A occur around every 25 years and affect huge numbers of people. The 1918 ‘Spanish flu’ pandemic is estimated to have killed 20 million people. Further pandemics have taken place in 1957–1958 (Asian flu), 1968–1969 (Hong Kong flu) and 1977 (Russian flu). An avian strain, H5N1, emerged in South East Asia in 2003 and is now considered endemic in many parts of South East Asia and remains a concern for public health (WHO, 2010).

The widespread use of NAIs during the 2009 pandemic brought its own problems. Resistance to oseltamavir emerged (Gulland, 2009), and some argued that the cure was worse than the disease (Strong et al., 2009). Further, a Cochrane review (Jefferson et al., 2009) found no good evidence that oseltamivir prevents secondary complications such as pneumonia, one of the main justifications for its widespread use in pandemic influenza. However, the relatively benign course of the 2009 pandemic should not provide false reassurance as to the risks associated with future pandemics.

Sore throat (pharyngitis)

Clinical features

In the UK, there has been a recent increase in rates of group A streptococcal infection. This includes invasive group A streptococcal infection (iGAS), associated with infection in normally sterile sites such as blood or tissue. The most common serotypes seen in England and Wales are emm 1, 3, and 89; emm 3 infections are associated with higher case fatality rates. The cause of the upsurge is unknown but may represent a natural periodic increase or alternatively excess transmission associated with high rates of influenza in 2008 (Lamagni et al., 2009).

Treatment

Treatment of viral sore throat is directed at symptomatic relief, for example with rest, antipyretics and aspirin gargles. Streptococcal sore throat is usually treated with antibiotics although the extent to which they shorten the duration of symptoms and reduce the incidence of suppurative complications is modest (Del Mar et al., 2004). Antibiotic treatment also reduces the incidence of non-suppurative complications so is likely to be of greater benefit where these are common. There is also an argument that treating to eradicate streptococcal carriage might reduce the risk of relapse or later streptococcal infection at other sites.

Broadly, there are three treatment strategies:

There is no correct approach and each has its advocates, although the problem of resistance has led to increasing pressure on prescribers to restrict empirical antibiotic use particularly for conditions such as pharyngitis that are frequently viral. The prevailing view is that antibiotics should not be routinely prescribed except where there is a high risk of severe infection, for instance, in immunocompromised patients (NICE, 2010).

Penicillins such as benzylpenicillin (penicillin G) or phenoxymethylpenicillin (penicillin V) have traditionally been regarded as the treatment of choice for streptococcal sore throat, but there is now convincing evidence that cephalosporins are more effective in terms of both clinical response and eradication of the organism from the oropharynx. This was summarised in a large meta-analysis of 40 studies in which 10-day courses of oral cephalosporins and penicillins were compared in the management of children with streptococcal pharyngitis (Casey and Pichichero, 2004). Bacteriological and clinical cure significantly favoured cephalosporins over penicillins, perhaps because penicillins are hydrolysed by β-lactamases produced by organisms such as anaerobes naturally resident in the oropharynx, whereas cephalosporins are not. The 10-day course length became accepted following earlier studies that compared the effect of different durations of penicillin treatment on bacteriological colonisation, but a recent systematic review (Atamimi et al., 2009) found comparable efficacy with shorter courses of newer antibiotics such as azithromycin.

Otitis media

Treatment

There has been much debate about whether or not antibiotics should be used for the initial treatment of acute otitis media. A meta-analysis combined seven clinical trials involving 2202 children and concluded that, although antibiotics confer a modest reduction in pain at 2–7 days, they do not reduce the incidence of short-term complications such as hearing problems and they do cause side effects (Glasziou et al., 2004). The benefit of antibiotic treatment may be greater in children under two than in older children (Damoiseaux et al., 2000), but in any case about 80% of cases treated without antibiotics will resolve spontaneously within 3 days. If antibiotic treatment is to be given, it should be effective against the three main bacterial pathogens: S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae and S. pyogenes. The streptococci are usually sensitive to penicillins, but these are much less active against H. influenzae, so the broader spectrum agents amoxicillin or ampicillin are preferred. These drugs have identical antibacterial activity, but amoxicillin is recommended for oral treatment since it is better absorbed from the gastro-intestinal tract. Patients with penicillin allergy may be treated with a later-generation cephalosporin (see later).

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, which are currently given routinely in the childhood vaccination schedule, may reduce the incidence of acute otitis media, although a recent review (Jansen et al., 2009) found only modest benefit. No benefit was found for influenza vaccination (Hoberman et al., 2003). Long-term antibiotic prophylaxis might have a role in some children (Leach and Morris, 2006), but any benefit has to be balanced against the risks.

Lower respiratory infections

Acute bronchitis and acute exacerbations of COPD

The importance of chronic bronchitis is that it renders the patient more susceptible to acute infections and more likely to suffer respiratory compromise as a result. These acute exacerbations of COPD are a frequent cause of morbidity and admission to hospital. An exacerbation is defined as ‘a sustained worsening of the patient’s symptoms from his or her usual stable state that is beyond normal day-to-day variations, and is acute in onset’ (NICE, 2004). Common symptoms include worsening breathlessness, cough, increased sputum production and change in sputum colour. It is important to remember that not all acute exacerbations of COPD have an infective aetiology since atmospheric pollutants are sometimes implicated.

Treatment

Despite the reservation that many cases are non-infective, current guidelines recommend that antibiotics are prescribed when an exacerbation is associated with more purulent sputum (NICE, 2004). There is no unequivocal evidence that one antibiotic is better than another, so recommendations for empiric treatment are based generally upon spectrum, side effects and cost. Most authorities favour either a tetracycline such as doxycycline or an aminopenicillin such as amoxicillin, since these agents cover most strains of S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae. Some people argue in favour of co-amoxiclav, which covers β-lactamase producing strains of H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis that are therefore resistant to amoxicillin, but this agent is more expensive and has a greater incidence of side effects. For penicillin-allergic patients for whom tetracyclines are contraindicated, neither the macrolide erythromycin nor the earlier oral cephalosporins such as cefalexin or cefradine are sufficiently active against H. influenzae for empiric use. However, both clarithromycin and newer oral cephalosporins such as cefixime are active against haemophili while retaining activity against pneumococci.

Second-line agents

A number of other drugs are promoted for the treatment of COPD exacerbations. Of these, azithromycin is not recommended, as it is less active than clarithromycin against S. pneumoniae. The activity of ciprofloxacin against S. pneumoniae is insufficient to justify its use as monotherapy against pneumococcal infections (although it has useful activity against H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis), and levofloxacin (which is the active isomer of ofloxacin) does not seem to offer any great microbiological advantage. Moxifloxacin is a quinolone that retains activity against Gram-negative organisms such as Haemophilus and Moraxella but has greater activity against Gram-positives such as S. pneumoniae. It has been favourably compared to standard treatment in exacerbations of COPD (Wilson et al., 2004). However, its use has been limited by the high incidence of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) associated with quinolone use, and rarely the development of life-threatening hepatic toxicity.

Bronchiolitis

The treatment of bronchiolitis is mainly supportive and consists of oxygen, adequate hydration and ventilatory assistance if required. Severe cases of respiratory syncytial virus disease may be treated with ribavirin, a synthetic nucleoside administered by nebuliser. There is limited evidence for its efficacy and it is currently only recommended for use in immunocompromised patients to reduce the duration of viral shedding (Yanney and Vyas, 2008).

Babies born earlier than 35 weeks of gestation or those less than 6 months of age at the onset of the respiratory syncytial virus season are at high risk of the disease. Likewise, infants under two years of age with chronic lung disease or severe immunodeficiency, or under 6 months of age with congenital heart disease are similarly at high risk, and all are candidates for prophylactic treatment with palivizumab. This is a humanised monoclonal antibody used for passive immunisation against respiratory syncytial virus (JCVI, 2005). There is currently no vaccine against RSV.

Pneumonia

Community-acquired pneumonia

Causative organisms

The causes of CAP are summarised in Table 35.1. The most common vegetative bacterial causes are S. pneumoniae, the pneumococcus, which can cause both lobar and bronchopneumonia, and non-capsulate strains of H. influenzae which usually give rise to bronchopneumonia.

| Organism | Comments |

|---|---|

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Classically causes lobar pneumonia, bronchopneumonia now common |

| Haemophilus influenzae | Cause of bronchopneumonia, usually non-capsulate strains |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Severe pneumonia with abscess formation, typically following influenza |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Friedlander’s bacillus, causing an uncommon but severe necrotising pneumonia |

| Legionella pneumophila | Particularly serogroup 1; causes Legionnaire’s disease, usually acquired from aquatic environmental sources |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Cause of acute pneumonia in young people, respiratory symptoms often overshadowed by systemic upset |

| Chlamydophila pneumoniae | Mild but prolonged illness usually seen in older people, respiratory symptoms often overshadowed by systemic upset |

| Chlamydophila psittaci | Causes psittacosis, a respiratory and multisystem disease acquired from infected birds |

| Coxiella burnetii | Causes Q fever, a respiratory and multisystem disease acquired from animals such as sheep |

| Viruses | Several viruses can cause pneumonia in adults, including influenza, parainfluenza and varicella zoster viruses |

Diagnosis

In pneumococcal disease, blood cultures are frequently positive and national guidance (Lim et al., 2009) suggests that laboratories should also offer plasma and urine testing for pneumococcal antigen. Legionella infection may be diagnosed by culture (if appropriate media are used) or by urinary antigen testing, but culture of Mycoplasma and Chlamydophila species is beyond the scope of most routine diagnostic laboratories. Viruses may be detected by immunofluorescence, by viral culture or by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), but timely diagnosis requires a good specimen such as bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. In practice, the aetiology of atypical pneumonia is usually determined serologically (for instance, by acute and convalescent antibody testing), if at all.

Targeted treatment

The treatment of choice for pneumococcal pneumonia is benzylpenicillin or amoxicillin. Erythromycin monotherapy may be used in penicillin-allergic patients, but resistance rates are rising, macrolides are bacteriostatic rather than bactericidal and the comparative efficacy of this approach is not known. There is retrospective evidence that combination therapy using both a β-lactam and a macrolide can reduce mortality in patients whose pneumonia is complicated by pneumococcal bacteraemia (Martinez et al., 2003).

Treatment recommendations for Legionnaire’s disease are based on a retrospective review of the famous Philadelphia outbreak of 1976 (Fraser et al., 1977), in which two deaths occurred among the 18 patients who were given erythromycin, compared to 16 deaths in 71 patients treated with penicillin or amoxicillin. This observation accords with the facts that Legionella is an intracellular pathogen and that macrolides penetrate more efficiently than β-lactams into cells. Azithromycin is probably the most effective of the macrolide/azalide derivatives, but clinical evidence to confirm this is lacking. Other agents with proven clinical efficacy and good intracellular activity against Legionella include rifampicin and quinolones. There have been no randomised controlled clinical trials, nor are there likely to be. Guidance, based on observation studies, suggests non-severe cases should be treated with an oral fluoroquinolone (with a macrolide as an alternative), and severe cases treated with a combination of a fluoroquinolone plus either a macrolide or rifampicin, de-escalating to a fluoroquinolone as the sole agent after the first few days (Lim et al., 2009). Treatment is not recommended for the non-pneumonic form of legionellosis (Pontiac fever) which presents as a self-limiting flu-like illness.

Empiric treatment

All of the foregoing recommendations presuppose that the infecting organism is known before treatment is commenced. In practice, this is rarely the case and therapy will initially be empirical or best-guess in nature (Table 35.2). The most authoritative recommendations for the initial treatment of CAP are those produced by the British Thoracic Society (Lim et al., 2009). For mild disease, these recommend treatment with amoxicillin, providing activity against pneumococci and most strains of H. influenzae, with doxycycline or clarithromycin being the preferred alternatives in penicillin-allergic patients. However, for moderate or severe disease requiring admission to hospital, they take the view that, until the aetiology is known, treatment should cover both ‘typical’ causes (such as S. pneumoniae and H. influenza) and atypical causes (such as M. pneumoniae, Chlamydophila species and Legionella). For patients with moderate or severe CAP, the guidelines therefore recommend a combination of a β-lactam drug plus a macrolide, the exact choice of agent and route being decided according to the clinical severity of the infection. In practice, this is usually interpreted as amoxicillin plus a macrolide for less severe disease, and co-amoxiclav plus a macrolide (or cefuroxime plus a macrolide) for more severe disease. Severity is assessed according to clinical parameters and outcome predicted by use of one of a number of assessment tools such as CURB-65, based on the onset of Confusion, the serum Urea, the Respiratory rate, the Blood pressure and age >65 years.

| Scenario | Typical regimen | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Mild to moderate pneumonia, organism unknown | Amoxicillin plus a macrolide | Amoxicillin covers S. pneumoniae and most H. influenzae while macrolide provides cover against atypical pathogens. It is debatable whether clinical outcomes are improved by using antibiotics active against atypical pathogens in all-cause non-severe community-acquired pneumonia |

| Severe pneumonia, organism unknown | Co-amoxiclav plus a macrolide Cefuroxime plus a macrolide in penicillin allergy | Co-amoxiclav and cefuroxime provide cover against S. aureus, coliforms and β-lactamase producing haemophili while retaining the pneumococcal cover of amoxicillin |

| Pneumococcal pneumonia | Penicillin or amoxicillin or a macrolide | High-level penicillin resistance remains uncommon in the UK. |

| H. influenzae | Non-β-lactamase producing: amoxicillin β-lactamase producing: cefuroxime or co-amoxiclav | Also sensitive to quinolones |

| Staphylococcal pneumonia | Non-MRSA: flucloxacillin +/– a second agent such as rifampicin or fusidic acid MRSA: requires microbiology input, options include linezolid or glycopeptides | Isolation of S. aureus from sputum may reflect contamination with oropharyngeal commensals and should be interpreted cautiously. MRSA pneumonia may also be treated with linezolid |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Macrolide or tetracycline | Treat for 14 days |

| Chlamydophila spp. | Tetracycline preferred | Treat for 14 days |

| Legionella spp. | A fluoroquinolone such as ciprofloxacin. A macrolide such as clarithromycin is an alternative if intolerant. | Addition of a macrolide or rifampicin in severe cases |

Hospital-acquired (nosocomial) pneumonia

Causative organisms

The most frequent causes of HAP are Gram-negative bacilli (Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp.) and S. aureus, including MRSA (Box 35.1). However, it is important to remember that pneumococcal pneumonia may develop in hospitalised patients and also that hospital water supplies have been implicated in outbreaks and sporadic cases of Legionella infection. Further, it must be recognised that the common Gram-negative causes of nosocomial pneumonia will vary between hospitals and even between different units within the same hospital. This is especially true of ventilator-associated pneumonia, which for obvious reasons is usually acquired on intensive care units where broad-spectrum antibiotics are frequently used, and where there may be a particular ‘resident flora’ with an established antibiotic resistance pattern.

Treatment

The range of organisms causing nosocomial pneumonia is very large, so broad-spectrum empiric therapy is indicated. The choice of antibiotics will be influenced by preceding antibiotic therapy, the duration of hospital admission and above all by the individual unit’s experience with hospital bacteria. The combinations shown in Table 35.3 have all been used at some time and all have advantages and disadvantages. Several of the combinations include an aminoglycoside, and this may not be desirable in all patients. Single-agent therapy is attractive for ease of administration, and agents such as piperacillin-tazobactam and meropenem have suitably broad spectra that include activity against P. aeruginosa. Currently licensed β-lactam agents are inactive against MRSA infections; in such cases specialist management advice is required.

Table 35.3 Treatment regimens for hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)

| Regimen | Comments |

|---|---|

| Co-amoxiclav | Good activity against community-associated pathogens, many Enterobacteriaceae and S. aureus. Recommended for early-onset HAP (within 5 days of admission) in antibiotic naïve patients without other risk factors |

| Ureidopenicillin plus aminoglycoside (e.g. piperacillin plus gentamicin) | Good activity against Gram-negative bacilli such as P. aeruginosa and also against pneumococci. Combination of piperacillin with the β-lactamase inhibitor tazobactam, currently the only ureidopenicillin product marketed in the UK, extends the spectrum to include S. aureus (not MRSA), anaerobes and some strains of E. coli, Klebsiella, etc. that are resistant to piperacillin alone. Piperacillin-tazobactam can also be used reliably as monotherapy |

| Cephalosporin plus an aminoglycoside (e.g. cefuroxime plus gentamicin) | Good activity against Gram-negative bacilli such as E. coli, Klebsiella, and Gram-positive organisms, but poor against P. aeruginosa and anaerobes |

| Clindamycin plus aminoglycoside | Good activity against Gram-positive organisms and anaerobes but much less so against Gram-negatives. Favoured in the USA where metronidazole is unpopular for the treatment of anaerobic infections |

| Ciprofloxacin plus glycopeptide (vancomycin or teicoplanin) | Ciprofloxacin provides good activity against most Gram-negative bacilli including P. aeruginosa. Glycopeptide provides activity against S. aureus (including MRSA) and pneumococci, although its penetration into the respiratory tract is relatively poor |

| Meropenem (monotherapy) | Broad-spectrum agent including activity against Extended Spectrum Beta Lactamase (ESBL) producing Enterobacteriaceae. Not active against MRSA. Ertapenem does not cover Pseudomonas spp. or Acinetobacter spp. so is unsuitable |

| Linezolid combinations | It is increasingly necessary to cover MRSA in empiric or targeted treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Traditional options include glycopeptides and, where the prevailing strains are sensitive, aminoglycosides, but there are concerns about penetration into the lung. Linezolid, an oxazolidinone, provides reliable activity |

| Aztreonam combinations | Good activity against gram-negative bacilli Including Pseudomonas but offers no activity against anaerobic or Gram-positive organisms. Expensive. A β-lactam agent that can be used safely in patients with history of severe penicillin allergy |

| Temocillin | Excellent activity against Gram-negative organisms including ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. No activity against Gram-positive organisms and Pseudomonas |

| Ceftazidime (monotherapy) | Very active against Gram-negative bacilli including Pseudomonas but less so against Gram-positive organisms and anaerobes. Due to the high incidence of Clostridium difficile infection and selection of multi-resistant organisms associated with its use, this agent has largely been superseded by other newer agents |

Prevention

General strategies for minimising the incidence of HAP include early postoperative mobilisation, analgesia, physiotherapy and promotion of rational antibiotic prescribing. The Department of Health’s Saving Lives programme makes specific recommendations for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia (DoH, 2007), including head of bed elevation, sedation holding to reduce the duration of mechanical ventilation and good general hygiene of tubing management and suction.

Another strategy proposed for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia is selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD), based on the premise that the infecting organisms initially colonise the patient’s oropharynx or intestinal tract (Kallett and Quinn, 2005). By administering non-absorbable antibiotics such as an aminoglycoside or colistin to the gut, and applying a paste containing these agents to the oropharynx, it is proposed that the potential causative organisms will be eradicated and the incidence of pneumonia thereby reduced. In some centres, an antifungal agent such as amphotericin B is added; others also advocate addition of a systemic broad-spectrum agent such as cefotaxime.

The role of selective decontamination of the digestive tract remains controversial. Recent guidelines (Masterton et al., 2008) recommend its consideration in patients in whom mechanical ventilation is anticipated for more than 48 h. Whether any benefits really outweigh the risks is unclear.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is caused by a coronavirus (SARS-associated coronavirus or SARS CoV). Clinically it causes pneumonitis, presenting with a flu-like prodrome and progressing to dyspnoea, dry cough and often adult respiratory distress syndrome, requiring ventilatory support. Treatment is largely supportive. It was first described in 2003 (Drosten et al., 2003) after a large outbreak originating in China spread throughout the Americas, Europe and Asia. The outbreak terminated in that year, with only small numbers of cases occurring since. Many experts predict that SARS will re-emerge.

Cystic fibrosis

Treatment

The treatment of infection in a child with cystic fibrosis will probably be directed against staphylococci, for which the usual anti-staphylococcal antibiotics such as flucloxacillin or erythromycin can be used. Once the patient is colonised by P. aeruginosa, treatment depends on early and vigorous therapy with antipseudomonal antibiotics (see Table 35.4). At first isolation of P. aeruginosa, eradication is attempted with oral ciprofloxacin and a nebulised antibiotic such as colistin. For chronically colonised patients, regular prophylactic intravenous treatment is given with a β-lactam/aminoglycoside combination such as ceftazidime plus tobramycin. Agents such as meropenem or a quinolone are usually reserved for treatment failures or when resistant organisms are encountered. The prolonged use of ceftazidime or ciprofloxacin alone should be avoided if possible since strains of P. aeruginosa and some other Gram-negative bacilli may become resistant to these agents while the patient is receiving treatment. Other treatment modalities are emerging: in a multi-centre, randomised controlled trial, long-term low-dose azithromycin was associated with improvements in lung function in patients chronically infected with P. aeruginosa (Saiman et al., 2003).

| Antibiotic | Comment |

|---|---|

| Ticarcillin | One of the first β-lactam agents effective against Pseudomonas but now considered insufficiently active. In combination with the β-lactamase inhibitor clavulanic acid, it may be active against some otherwise resistant strains |

| Ureidopenicillins | Piperacillin, formulated in combination with the β-lactamase inhibitor tazobactam, is the only one of these agents now available in the UK |

| Monobactams | Aztreonam offers good activity against Gram-negative organisms but no activity against Gram-positive organisms |

| Cephalosporins | Ceftazidime is the most active antipseudomonal cephalosporin and is very active against other Gram-negative bacilli. It has rather lower activity against Gram-positive bacteria. Pseudomonas may develop resistance during treatment |

| Aminoglycosides | Gentamicin and tobramycin have very similar activity against Pseudomonas; tobramycin is perhaps slightly more active. Netilmicin is less active, while amikacin may be active against some gentamicin-resistant strains |

| Quinolones | Ciprofloxacin can be given orally and parenterally but as with ceftazidime, resistance can develop while the patient is on treatment. Other quinolones such as ofloxacin, its L-isomer levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin have better Gram-positive spectrum but concomitantly less activity against Pseudomonas |

| Polymyxins | These peptide antibiotics are considered too toxic for systemic use in all but the most desperate cases, but colistin (polymyxin E) can be given by inhalation |

| Carbapenems | Broad-spectrum agents with good Gram-negative activity. Imipenem was the first of these drugs, but CNS toxicity and its requirement for combination with the renal dipeptidase inhibitor cilastatin have largely led to its replacement by meropenem. Doripenem is a newer carbapenem with similar activity to meropenem. Ertapenem has poor activity against P. aeruginosa |

The use of inhaled (usually nebulised) antibiotics as an adjunct to parenteral therapy has attracted attention, both for treatment of acute exacerbations and for longer-term use in an attempt to reduce the Pseudomonas load. Agents which have been administered in this way include colistin, tobramycin and other aminoglycosides, carbenicillin and ceftazidime. The best evidence that long-term administration can be beneficial comes from a large multi-centre trial of nebulised tobramycin (Moss, 2001) in which 520 patients were randomised to receive once-daily nebulised tobramycin or placebo in on–off cycles for 24 weeks, followed by open-label tobramycin to complete 2 years of study. Nebulised tobramycin was safe and well tolerated and was associated with a reduction in hospitalisation and improvements in lung function. This was at the expense of a degree of tobramycin resistance, although this did not seem to be clinically significant.

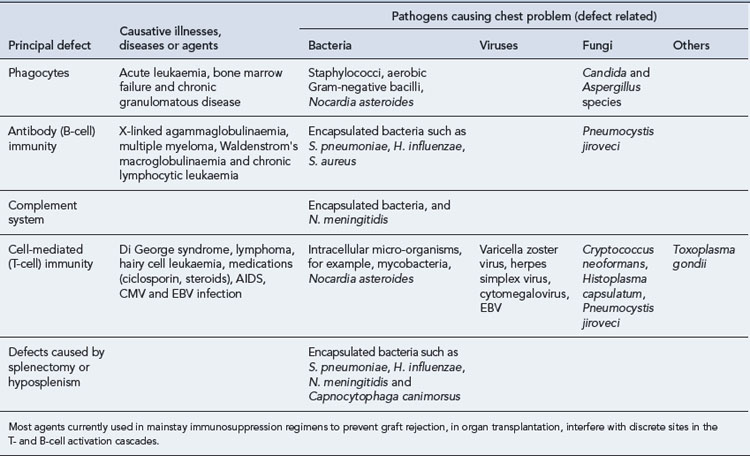

Respiratory infection in the immunocompromised

The increased use of immunosuppressive agents, and to a lesser extent, the spread of HIV infection, has led to increasing numbers of immunocompromised individuals. Respiratory tract infections, in general, and pneumonia, in particular, are frequent complications. Morbidity and mortality are high; so rapid recognition, accurate diagnosis and correct treatment are of prime importance. Diagnosis may be complicated by the sheer number of potential pathogens, the problem of distinguishing infection from non-infective conditions such as malignant infiltration or radiation pneumonitis, and non-specific or delayed presentation. The nature, duration and severity of the underlying immune defect, together with specific epidemiologic or environmental factors, influence the risk of infection by different organisms. These are summarised briefly in Table 35.5. Common therapeutic problems are summarised in Table 35.6.

| Problem | Comments |

|---|---|

| No pathogens isolated on sputum culture | Possibilities include an inadequate specimen such as saliva, non-infected or sterilised sputum, or a pathogen that cannot be cultured on routine media such as Chlamydophila pneumoniae or Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Pneumococci are susceptible to autolysis and may fail to grow even from a well-taken specimen, particularly if transport to the laboratory is delayed |

| Staphylococcus aureus isolated (including MRSA) | S. aureus pneumonia is a severe disease with characteristic clinical features, often associated with bacteraemia. However, the organism is frequently isolated from the sputum of patients with bronchitis or bronchopneumonia. In these instances, it usually reflects contamination of the specimen with oropharyngeal commensals although some patients undoubtedly have a clinical infection requiring anti-staphylococcal antibiotics |

| Candida spp. isolated | Unless there are reasons to suspect Candida pneumonia (as a consequence of neutropenia, for example), the isolation of yeasts is likely to reflect oropharyngeal contamination of the specimen. Yeasts can be carried commensally in the mouth, particularly in the presence of dentures, but a search for clinically apparent mucocutaneous candidiasis should be made |

| Aspergillus spp. isolated | Invasive aspergillosis, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and aspergilloma should be considered. Alternatively, the finding might reflect inconsequential oropharyngeal carriage |

| Penicillin-resistant pneumococci isolated | Respiratory infections caused by strains with low-level resistance (MIC 0.1–1 mg/L) may be treated with penicillins. Strains with high-level resistance should be treated according to their sensitivity profile, for example, using a later-generation cephalosporin or a macrolide |

| Coliforms isolated | Significance depends on the clinical context: unlikely to be responsible for community-acquired infection unless there is bronchiectasis, but may be relevant to hospital-acquired infections particularly if present in pure culture |

| Failure of a chest infection to respond to antibiotics | Consider poor compliance, inadequate dosage, viral or otherwise insensitive aetiology. Remember that β-lactam drugs are ineffective against Chlamydophila, Mycoplasma and Legionella infections |

| Sore throat, no pathogens isolated | Consider viral aetiology, particularly glandular fever in teenagers and young adults |

| Persistent illness following treatment for pneumococcal pneumonia | Consider the possibility of an empyema (pus in the pleural space), a condition which usually requires surgical drainage |

Case 35.1

Answers

Case 35.2

Answers

Case 35.4

Answers

Atamimi S., Khalil A., Khalaiwi, et al. Short versus standard duration antibiotic therapy for acute streptococcal pharyngitis in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2009. CD004872 Available at http://www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ ab004872.html

Casey J.R., Pichichero M.E. Meta-analysis of cephalosporin versus penicillin treatment of Group A streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis in children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:866-882.

Damoiseaux R.A.M., Van Balen F.A.M., Hoes A.W., et al. Primary care based randomised, double blind trial of amoxicillin versus placebo for acute otitis media in children aged under 2 years. Br. Med. J.. 2000;320:350-354.

Del Mar C.B., Glasziou P.P., Spinks A.B. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2004. CD000023

Department of Health. Saving Lives: Reducing Infection, Delivering Clean and Safe Care. High Impact Intervention No 5: Care Bundle for Ventilated Patients (or Tracheostomy Where Appropriate). Available at http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_078124.pdf, 2007.

Drosten C., Gunther S., Preiser W., et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2003;348:1967-1976.

Fraser D.W., Tsai T.R., Orenstein W., et al. Legionnaire’s disease: description of an epidemic of pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med.. 1977;297:1189-1197.

Glasziou P.P., Del Mar C.B., Sanders S.L., et al. Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Library. (Issue 1):2004. CD000219

Gulland A. Oseltamivir resistant swine flu spreads in Welsh hospital. Br. Med. J.. 2009;339:b4975.

Health Protection Agency. Legionnaires’ disease in Residents of England and Wales – Nosocomial, Travel or Community Acquired Cases, 1980–2008. Available at http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1195733748327

Hoberman A., Greenberg D.P., Paradise, et al. Effectiveness of inactivated influenza vaccine in preventing acute otitis media in young children. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 2003;290(12):1608-1616.

Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation. Minutes of the JCVI RSV sub-group on Thursday 11, November 2004. Available at http://www.advisorybodies.doh.gov.uk/jcvi/mins111104rvi.htm, 2004.

Kallet R.H., Quinn T.E. The gastro-intestinal tract and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Respir. Care. 2005;50:910-923.

Jansen A.G., Hak E., Veenhoven R.H., et al. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines for preventing otitis media. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2009. CD001480

Jefferson T., Jones M., Doshi P., et al. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. Med. J.. 2009;339:b5106.

Lamagni T.L., Efstratiou A., Dennis J., et al. Increase in invasive group A streptococcal infections in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 2008–2009. Eurosurveillance. 2009;14:1-2.

Leach A.J., Morris P.S. Antibiotics for the prevention of acute and chronic suppurative otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2006. CD004401

Lim W.S., Baudouin S.V., George R.C., et al. British Thoracic Society guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax. 2009;64,(Suppl. III):iii1-iii55.

Martinez J.A., Horcajada J.P., Almeda M., et al. Addition of a macrolide to a beta-lactam based empirical antibiotic regimen is associated with lower in-hospital mortality for patients with bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis.. 2003;36:389-395.

Masterton R.G., Galloway A., French G., et al. Guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia in the UK: report of the Working Party on Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2008;62:5-34.

Moss R.B. Administration of aerosolized antibiotics in cystic fibrosis patients. Chest. 2001;120:107-113.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Oseltamivir, Amantadine and Zanamavir for the Prophylaxis of Influenza. TA 158. London: NICE, 2008. Available at http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA158

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Amantadine, Oseltamavir and Zanamavir for the Treatment of Influenza. TA 168. London: NICE, 2009. Available at http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA168

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. Clinical Guidance 12. London: NICE, 2004. Available at http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG12

NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Sore throat. Available at http://www.cks.nhs.uk/sore_throat_acute/management/detailed_answers/when_to_admit, 2010. #-329330

Saiman L., Marshall B.C., Mayer-Hamblett N., et al. Azithromycin in patients with cystic fibrosis chronically infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 2003;290:1749-1756.

Strong M., Burrows J., Redgrave P. A/H1N1 pandemic: Oseltamivir’s adverse events. Br. Med. J.. 2009;449:b3172.

Van Den Hoogen B.G., De Jong J.C., et al. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat. Med.. 2001;7:719-724.

Wilson R., Allegra L., Huchon G., et al. Short-term and long-term outcomes of moxifloxacin compared to standard antibiotic treatment in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Chest. 2004;125:953-964.

World Health Organisation. Update on human cases of highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) infection: 2009. Wkly Epidemiol. Rec.. 2010;85:49-51.

Yanney M., Vyas H. The treatment of bronchiolitis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2008;93:793-798.

Durrington H.J., Summers C. Recent changes in the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults. Br. Med. J.. 2008;336:1429-1433.

Falk G., Fahey T. C-reactive protein and community-acquired pneumonia in ambulatory care: systematic review of diagnostic accuracy studies. Fam. Pract.. 2009;26:10-21.

Moberley S., Holden J., Tatham D., et al. Vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in adults. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2008. CD000422

Nightingale C.H., Ambrose P.G., File T.M., editors. Community-Acquired Respiratory Tract Infections: Antimicrobial Management. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, 2003.

Santiago E., Mandell L., Woodhead M., et al. Respiratory Infections. London: Holder Education, 2006.