Chapter 3 Respiratory Failure

3 What are the clinical features of respiratory failure?

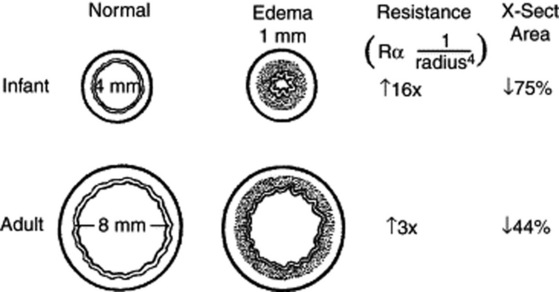

4 Why does respiratory resistance increase so significantly with inflammation of the respiratory tree?

The resistance to laminar air flow through a tube is inversely related to the radius to the fourth power (Poiseuille’s law). Modest decreases in the radius of the lumen of the airway can lead to dramatic increases in respiratory resistance when airway caliber is small (Fig. 3-1).

7 How do I know which of the numerous children with respiratory symptoms will progress to respiratory failure?

10 How can one tell if the respiratory failure is caused by an upper airway disease or by lower airway disease?

12 What is the value of a chest radiograph in evaluation of a child with suspected respiratory failure?

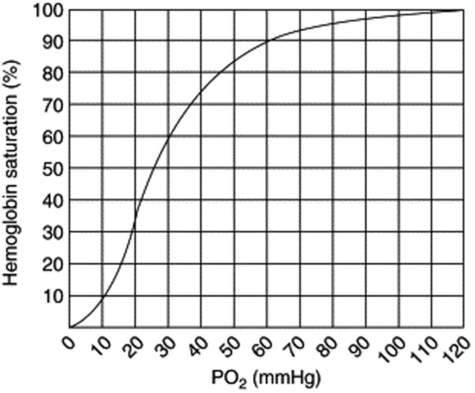

14 What’s the big deal if the oxygen saturation is 2–3% below normal?

The relationship between PO2 and saturation is not linear but sigmoidal. While there is little difference in PO2 between saturations of 99% and 96%, there is a much greater difference between 93% and 90%. In children with bronchiolitis, oxygen saturation below 95% during feeding was the most useful factor in identifying infants who would have a more severe course of illness. Sleeping children with respiratory illnesses often have transient periods of desaturation that require no intervention. Oxygen therapy and closer monitoring should be considered if the desaturation is persistent (Fig. 3-2).

16 Why are some children with severe respiratory distress well saturated, while others who look comfortable are hypoxemic?

17 Why do some patients with wheezing have a reduction in their oxygen saturation after bronchodilator treatment when they otherwise appear to be improving?

19 What is ARDS in children? Doesn’t the “A” stand for ADULT?

21 Why are some patients who meet the definition for respiratory failure not intubated and mechanically ventilated to normalize their blood gases?

22 Is endotracheal intubation the only way to manage an airway in respiratory distress?

23 What are the indications to intubate the trachea of a child?

Respiratory failure that is unlikely to be reversed quickly, especially if hypoxemia is present despite >60% oxygen administration

Respiratory failure that is unlikely to be reversed quickly, especially if hypoxemia is present despite >60% oxygen administration

Apnea, hypoventilation, or progressive respiratory exhaustion that requires ongoing mechanical ventilation

Apnea, hypoventilation, or progressive respiratory exhaustion that requires ongoing mechanical ventilation

Need for airway protection for children who have upper airway obstruction or an inability to protect their airway from aspiration

Need for airway protection for children who have upper airway obstruction or an inability to protect their airway from aspiration

Desire to decrease the work of breathing for patients in shock (under normal circumstances, work of breathing requires less than 5% of the total energy expenditure, but with respiratory distress it can demand up to 50%; in a shock state, energy can be better utilized for other essential body functions)

Desire to decrease the work of breathing for patients in shock (under normal circumstances, work of breathing requires less than 5% of the total energy expenditure, but with respiratory distress it can demand up to 50%; in a shock state, energy can be better utilized for other essential body functions)

Therapeutic interventions, such as tracheal administration of medications and suctioning for pulmonary toilet (mechanical ventilation is also required)

Therapeutic interventions, such as tracheal administration of medications and suctioning for pulmonary toilet (mechanical ventilation is also required)

24 What are the steps for emergency endotracheal intubation of a child?

1 Preoxygenate with bag-valve-mask ventilation with 100% oxygen.

2 Prepare all equipment, including suction, endotracheal tubes, and laryngoscopes.

3 Make certain an IV catheter is functioning well.

4 Apply cricoid pressure (Sellick maneuver) to prevent passive regurgitation and aspiration. (Keep applying pressure until endotracheal tube is known to be in the trachea.)

5 Administer atropine (for younger children), followed by a sedative agent and then a paralytic agent.

6 Perform laryngoscopy once paralysis is complete, and watch the endotracheal tube go through the vocal cords into the trachea.

7 Auscultate for equal breath sounds, and check for gurgling over the stomach, which suggests esophageal intubation. Observe symmetric chest expansion, misting in the tube with exhalation, improvement in oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry, and presence of CO2 by capnometry.

10 Obtain chest radiograph to check position of the tube and adjust accordingly.

25 Can a difficult endotracheal intubation be predicted?

| Congenital | Acquired |

|---|---|

| Micrognathia | Hoarseness/stridor/drooling |

| Macroglossia | Facial burns/singed facial hairs |

| Cleft or high-arched palate | Facial fractures/oral trauma |

| Protruding upper incisors | Foreign body |

| Small mouth | |

| Limited mobility of temporomandibular joint | |

26 What should you consider if a patient deteriorates after endotracheal intubation?

If an intubated patient’s condition deteriorates after endotracheal intubation, consider DOPE: