3 Respiratory Distress

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Clinical Presentation

Initial Assessment

The evaluation of a child with acute respiratory distress includes determining the severity as well as the underlying cause. Given that respiratory distress may range in severity from mild to severe, the clinical presentation can be quite varied. In all cases, the first key to the assessment is to ensure the patency of the airway, adequate breathing, and intact circulation (see Chapter 1). After these basic life support principles have been addressed, the physical examination may proceed.

History

A thorough history, including existing medical problems and recent events leading to the current presentation, provides important clues to the underlying cause (Table 3-1). For example, a patient with a foreign body obstruction or anaphylaxis may have an acute presentation of severe respiratory distress compared with a child with an infectious cause in whom the presentation may be more gradual.

Table 3-1 Focused History for a Patient with Respiratory Distress

| Component | Comments and Examples |

|---|---|

| Onset, duration, and chronicity |

Physical Examination

Vital Signs

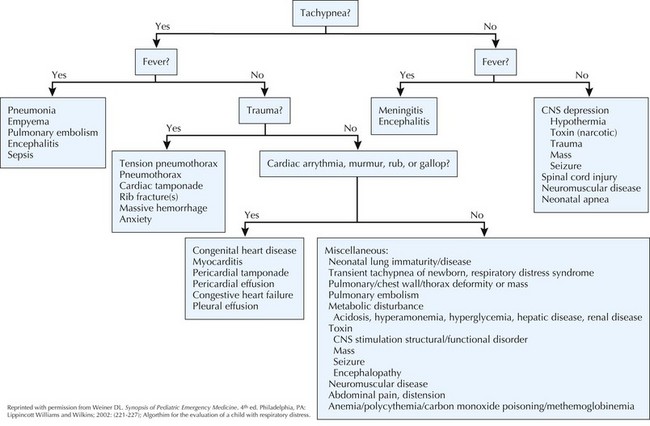

Vital signs, including temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and pain score, should be promptly obtained in all patients with respiratory distress. Pulse oximetry, although not classically part of the vital signs, should also be noted to detect hypoxia. Tachypnea (rapid breathing) is one of the most consistent findings among children with respiratory distress and may be caused by fever, hypoxemia, hypercarbia, metabolic acidosis, pain, or anxiety (Table 3-2). However, many children with significant respiratory disease may have normal respiratory rates. Bradypnea may also occur in response to hypoxia in younger infants or from respiratory fatigue, CNS depression, or increased intracranial pressure. Pulsus paradoxus, an exaggeration of the normal decrease in blood pressure during inspiration, of greater than 10 mm Hg correlates well with the degree of airway obstruction but is very difficult to assess in children and therefore not routinely measured.

| Age | Breaths per Minute |

|---|---|

| Younger than 2 months | >60 |

| 2-12 months | >50 |

| 1-5 years | >40 |

| Older than 5 years | >20 |

Respiratory Examination

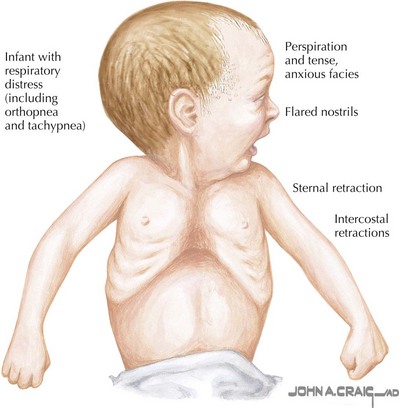

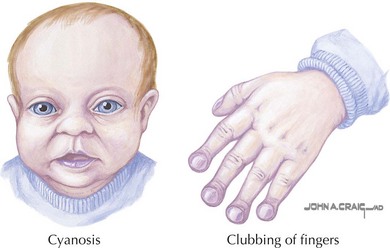

The respiratory examination can give many clues as to the cause of respiratory distress because the clinical manifestations may be indicative of the location of the disease process within the upper or lower respiratory tract (or both) (Figure 3-1). Initially, observe the general appearance of the patient, specifically for depth, rhythm, and symmetry of respirations; color; increased work of breathing; perfusion; and mental status. Patients with complete upper airway obstruction have aphonia, which is no audible speech, cry, or cough secondary to lack of effective air movement caused by a foreign body, angioedema, or epiglottitis. The presence of nasal flaring indicates dyspnea or upper airway obstruction. Facial edema and urticaria may signify anaphylaxis. The patient may show signs of acute or chronic hypoxemia in the form of cyanosis or clubbing, respectively (Figure 3-2). Cyanosis is not evident until more than 5 g/dL of hemoglobin is desaturated, which correlates with an oxygen saturation of less than 70% to 75%. Cyanosis is a late finding in children with hypoxemia and is seen in children with low cardiac output as well as low arterial oxygen saturation. Cyanosis in the presence of normal oxygen saturation may be indicative of methemoglobinemia.

Sounds noted on auscultation are useful in localizing the source of respiratory distress. Stertor, a sound from the upper airways resembling snoring, may indicate a degree of adenotonsillar hypertrophy, nasal congestion, or neuromuscular weakness. Hoarseness points to laryngeal or vocal cord dysfunction. A barky cough results from subglottic or tracheal obstruction. Stridor indicates abnormal turbulent air flow through a partially obstructed extrathoracic airway and can occur in both phases of respiration; if occurring during inspiration, the obstruction is most likely in the glottic or subglottic region; if in the expiratory phase, the sound is generated from the carina or below; if present in both phases (biphasic), the trachea may be involved (see Chapter 36). Grunting is a means by which patients generate intrinsic end-expiratory pressure against a closed glottis; in children, this is a sign of hypoxia that may indicate lower airway disease such as pneumonia. Grunting may also be associated with pain or an intraabdominal process. Retractions, the inward collapse of the chest wall, are caused by high negative intrathoracic pressure with increased respiratory effort and are more obvious in children because of the high compliance of the chest wall. Supraclavicular and suprasternal retractions occur in patients with upper airway obstruction; intercostal retractions signify lower tract disease or obstruction. Subcostal retractions may be seen with either upper or lower airway obstruction. Thoracoabdominal dissociation, or paradoxical breathing in which the chest collapses on inspiration while the abdomen is protruding, is a sign of respiratory failure from weakness or fatigue. Wheezing is classically a sign of lower airway obstruction and usually occurs during expiration (see Chapter 37). It may be associated with underlying medical conditions such as asthma, bronchiolitis, congestive heart failure, and congenital malformations. Inspiratory wheezing may indicate upper airway extrathoracic obstruction secondary to a foreign body, edema, or a fixed intrathoracic obstruction. Crackles (or rales) indicate fluid in the small- to medium-sized airways and may be heard in pneumonia, bronchiolitis, or myocarditis with heart failure. Rhonchi (coarse rales) involve secretions in the larger bronchi. A friction rub is heard when the pleura are inflamed and may be heard in patients with pneumonia or lung abscess and with pleural effusions or empyema. Bronchophony, egophony, and whispered pectoriloquy, which may be difficult to elicit in pediatric patients, occur because of consolidations in or around the lung, as seen in patients with pneumonia or pleural effusion.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of respiratory distress can be summarized by organ system (Box 3-1).

Box 3-1

Differential Diagnosis of Respiratory Distress*

Upper airway (nasopharynx, oropharynx, larynx, trachea, bronchi)

Lower airway (bronchioles, acini, interstitium)

Reprinted with permission from Weiner DL: Synopsis of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, ed 4. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002, pp 221-227.

Evaluation and Management

Algorithm

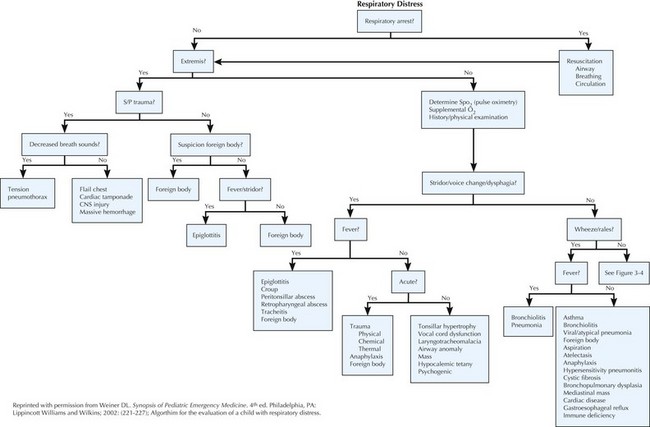

An algorithmic approach that merges history and physical examination findings is helpful in eliciting the underlying cause of respiratory distress while also providing guidance for further testing (Figures 3-3 and 3-4).

Initial Management

The emergent evaluation of children with respiratory distress must first identify the respiratory status of the patient by ensuring the patency of the airway, breathing, and circulation (see Chapter 1) before proceeding. Patients in severe respiratory distress and impending respiratory failure should be evaluated immediately for the life-threatening causes of respiratory distress, which include complete or rapidly progressing partial airway obstruction, as in foreign body or epiglottitis, tension pneumothorax, and cardiac tamponade (Table 3-2 and Figure 3-4). Children with respiratory failure secondary to inadequate oxygenation or ventilation may exhibit pallor or central cyanosis; altered mental status; decreased chest wall movement; or marked tachypnea, bradypnea, or apnea.

Diagnostic Studies

Blood Tests

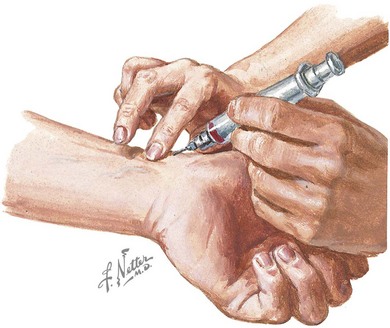

Blood tests may also be useful to guide further therapy. A blood gas analysis, ideally an arterial sample, will reflect oxygenation, ventilation, and acid–base status, all of which may be amenable to immediate treatment (Figure 3-5). A venous blood gas analysis can provide some information about ventilation but is less useful in assessing oxygenation. Blood chemistry analysis that includes electrolytes and total carbon dioxide may provide evidence of a metabolic acidosis that could be contributing to the patient’s respiratory distress. Other tests such as carboxyhemoglobin or methemoglobin levels may be useful if the clinical history and physical examination raise suspicion. A complete blood count can indicate an elevated white blood cell count that may support a diagnosis of infection or may show anemia or polycythemia, both of which may lead to tachypnea. A toxicology screen may be useful in a child with altered mental status, respiratory depression (opiate overdose), or unexplained tachypnea (metabolic acidosis). Specimens should be sent for microbiologic culture as deemed necessary.

Lipps-Kim J. Respiratory distress. In: Zaoutis LB, Chiang VW, editors. Comprehensive Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:218-222.

Perez Fontan JJ, Haddad GG. Respiratory pathophysiology. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2004:1376-1379.

Weiner DL. Respiratory distress. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, editors. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:553-564.

Weiner DL. Synopsis of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. pp 221-227

Weiner DL, Fleisher GR: Emergent evaluation of acute respiratory distress in children. In Wiley JF, editor: UpToDate Online 18.3. www.uptodate.com/contents/emergent-evaluation-of-acute-respiratory-distress-in-children.