Respiratory disorders

Notable features of respiratory disorders are:

• Worldwide, respiratory disorders are the most common cause of death in children

• In the UK, respiratory disorders account for 50% of consultations with general practitioners for acute illness in young children and a third of consultations in older children

• Respiratory disorders are responsible for about 25% of acute paediatric admissions to hospital, some of which are life-threatening

• Asthma is the most common chronic illness of childhood in the UK

• Cystic fibrosis is the most common inherited life-limiting disorder in Caucasians.

Respiratory infections

Host and environmental factors

• Parental smoking, especially maternal

• Poor socioeconomic status – large family size, overcrowded, damp housing

• Underlying lung disease – such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia in infants who were born preterm, cystic fibrosis or asthma

• Haemodynamically significant congenital heart disease

• Immunodeficiency (either primary, see Ch. 14, or secondary, e.g. from HIV infection or chemotherapy).

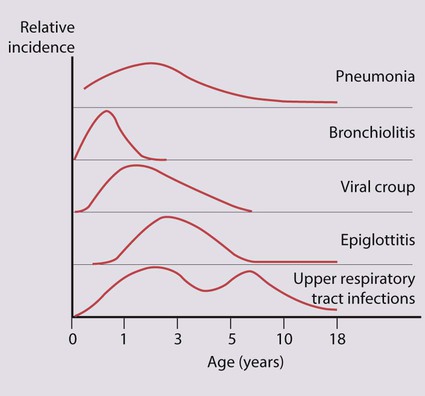

The child’s age influences the prevalence and severity of infections (Fig. 16.1). It is in infancy that serious respiratory illness requiring hospital admission is most common and the risk of death is greatest. There is an increased frequency of infections when the child or older siblings start nursery or school. Repeated upper respiratory tract infection is common and rarely indicates underlying disease.

Upper respiratory tract infection (URTI)

Acute infection of the middle ear (acute otitis media)

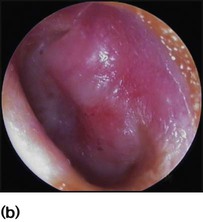

Most children will have at least one episode of acute otitis media (OM). This is most common at 6–12 months of age. Up to 20% will have three or more episodes. Infants and young children are prone to acute otitis media because their Eustachian tubes are short, horizontal and function poorly. There is pain in the ear and fever. Every child with a fever must have their tympanic membranes examined (Fig. 16.2a–d). In acute otitis media, the tympanic membrane is seen to be bright red and bulging with loss of the normal light reflection (Fig. 16.2b). Occasionally, there is acute perforation of the eardrum with pus visible in the external canal. Pathogens include viruses, especially RSV and rhinovirus, and bacteria including pneumococcus, non-typeable H. influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis. Serious complications are mastoiditis and meningitis, but are now uncommon. Pain should be treated with an analgesic such as paracetamol or ibuprofen. Regular analgesia is more effective than intermittent (as required) and may be needed for up to a week until the acute inflammation has resolved. Most cases of acute otitis media resolve spontaneously. Antibiotics marginally shorten the duration of pain but have not been shown to reduce the risk of hearing loss (see Ch. 5). It is often useful to give the parents a prescription, but ask them to use it only if the child remains unwell after 2–3 days. Amoxicillin is widely used. Neither decongestants nor antihistamines are beneficial.

Recurrent ear infections can lead to otitis media with effusion (OME or glue ear or serous otitis media). Children are asymptomatic apart from possible decreased hearing. The eardrum is seen to be dull and retracted, often with a fluid level visible (Fig. 16.2c). Confirmation of otitis media with effusion can be gained by a flat trace on tympanometry, in conjunction with evidence of a conductive loss on pure tone audiometry (possible if >4 years old), or reduced hearing on a distraction hearing test in younger children. Otitis media with effusion is very common between the ages of 2 and 7 years, with peak incidence between 2.5 and 5 years. This condition usually resolves spontaneously. Cochrane reviews have shown no evidence of long-term benefit from the use of antibiotics, steroids or decongestants. Otitis media with effusion is the most common cause of conductive hearing loss in children and can interfere with normal speech development and result in learning difficulties in school. In such children insertion of ventilation tubes (grommets, Fig. 16.2d) can be beneficial, but there is evidence, again from Cochrane reviews, that adenoidectomy can offer more long-term benefit. It is believed that the adenoids can harbour organisms within biofilms that contribute to infection spreading up the Eustachian tubes. In addition, grossly hypertrophied adenoids may obstruct and affect the function of the Eustachian tubes, leading to poor ventilation of the middle ear and subsequent recurrent infections. In practice, children with recurrent URTIs and chronic glue ear that do not resolve with conservative measures undergo grommet insertion. If these problems recur after grommet extrusion, reinsertion of grommets with adjuvant adenoidectomy is usually advocated.

Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy

• Recurrent severe tonsillitis (as opposed to recurrent URTIs) – tonsillectomy reduces the number of episodes of tonsillitis by a third, e.g. from three to two per year, but is unlikely to benefit mild symptoms.

• A peritonsillar abscess (quinsy)

• Obstructive sleep apnoea (the adenoids will also normally be removed).

Laryngeal and tracheal infections

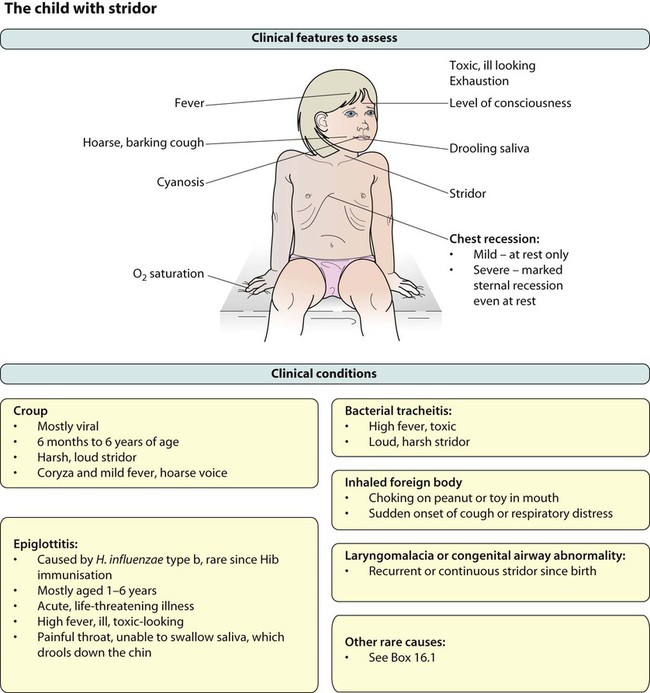

The mucosal inflammation and swelling produced by laryngeal and tracheal infections can rapidly cause life-threatening obstruction of the airway in young children. Several conditions can cause acute upper airways obstruction (Box 16.1). They are characterised by:

• Stridor, a rasping sound heard predominantly on inspiration

• Hoarseness due to inflammation of the vocal cords

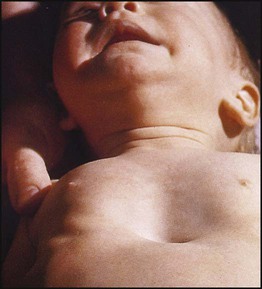

The severity of upper airways obstruction is best assessed clinically by the degree of chest retraction (none, only on crying, at rest) and degree of stridor (none, only on crying, at rest or biphasic) (Fig. 16.3).

Acute epiglottitis

There is intense swelling of the epiglottis and surrounding tissues associated with septicaemia. Epiglottitis is most common in children aged 1–6 years but affects all age groups. It is important to distinguish clinically between epiglottitis and croup (Table 16.1), as they require quite different treatment.

Table 16.1

Clinical features of croup (viral laryngotracheitis) and epiglottitis

| Croup | Epiglottitis | |

| Onset | Over days | Over hours |

| Preceding coryza | Yes | No |

| Cough | Severe, barking | Absent or slight |

| Able to drink | Yes | No |

| Drooling saliva | No | Yes |

| Appearance | Unwell | Toxic, very ill |

| Fever | <38.5°C | >38.5°C |

| Stridor | Harsh, rasping | Soft, whispering |

| Voice, cry | Hoarse | Muffled, reluctant to speak |

The onset of epiglottitis is often very acute (see Case History 16.1), with:

• high fever in an ill, toxic-looking child

• an intensely painful throat that prevents the child from speaking or swallowing; saliva drools down the chin

• soft inspiratory stridor and rapidly increasing respiratory difficulty over hours

• the child sitting immobile, upright, with an open mouth to optimise the airway.

Bronchiolitis

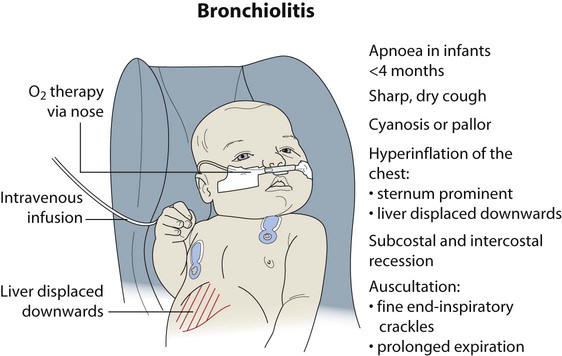

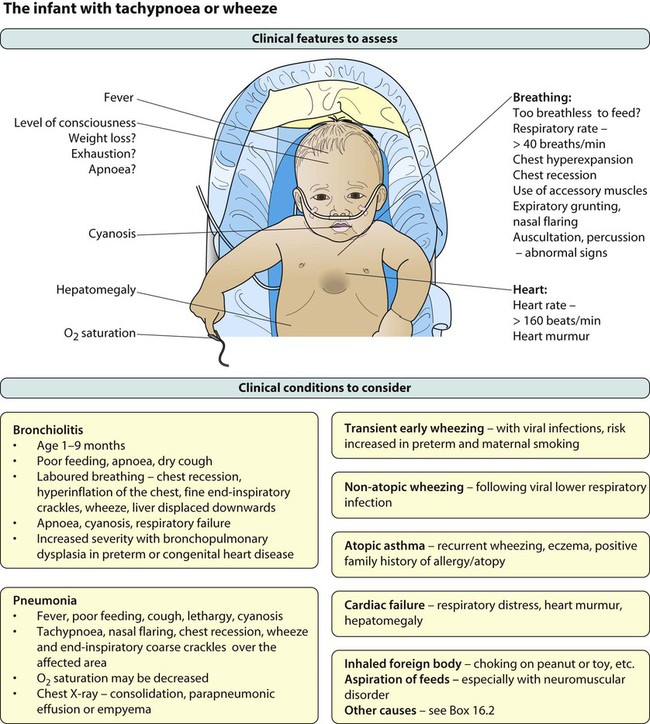

Clinical features

Coryzal symptoms precede a dry cough and increasing breathlessness. Feeding difficulty associated with increasing dyspnoea is often the reason for admission to hospital. Recurrent apnoea is a serious complication, especially in young infants. Infants born prematurely who develop bronchopulmonary dysplasia or with other underlying lung disease, such as cystic fibrosis or have congenital heart disease, are most at risk from severe bronchiolitis. The characteristic findings on examination (Fig. 16.5) are:

Investigations

Respiratory viruses are now usually identified by PCR analysis of nasopharyngeal secretions. A chest X-ray is unnecessary in straightforward cases, but if performed, typically shows hyperinflation of the lungs due to small airways obstruction, air trapping (Fig. 16.6) and often focal atelectasis. Pulse oximetry is used to measure and monitor arterial oxygen saturation continuously. Blood gas analysis, usually a capillary sample, is only performed in severe disease to identify hypercarbia when additional ventilatory support is considered.

Pneumonia

The pathogens causing pneumonia vary according to the child’s age:

• Newborn – organisms from the mother’s genital tract, particularly group B streptococcus, but also Gram-negative enterococci

• Infants and young children – respiratory viruses, particularly RSV, are most common, but bacterial infections include Streptococcus pneumoniae or Haemophilus influenzae. Bordetella pertussis and Chlamydia trachomatis can also cause pneumonia at this age. An infrequent but serious cause is Staphylococcus aureus

• Children over 5 years – Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae are the main causes.

• At all ages Mycobacterium tuberculosis should be considered.

Clinical features

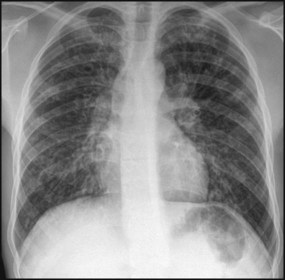

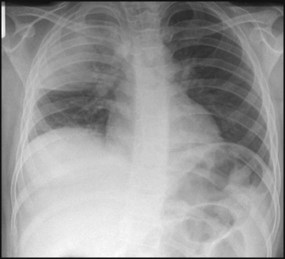

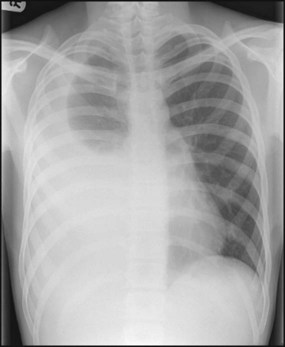

A chest X-ray may confirm the diagnosis, but with the exception of a classic lobar pneumonia characteristic of Streptococcus pneumoniae (Fig. 16.7), a chest X-ray cannot differentiate between bacterial and viral pneumonia. In younger children, a nasopharyngeal aspirate is useful to identify viral causes, but blood tests, including full blood count and acute-phase reactants, are generally unhelpful in differentiating between a viral and bacterial cause. A small proportion of pneumonias are associated with a pleural effusion, where there may be blunting of the costophrenic angle on the chest X-ray. Some of these effusions develop into empyema and fibrin strands may form, leading to septations, which make drainage difficult (Fig. 16.8). The incidence of childhood empyema has risen over the last decade, the precise reason for which remains unclear. Ultrasound of the chest will often distinguish between parapneumonic effusion and empyema.

Asthma

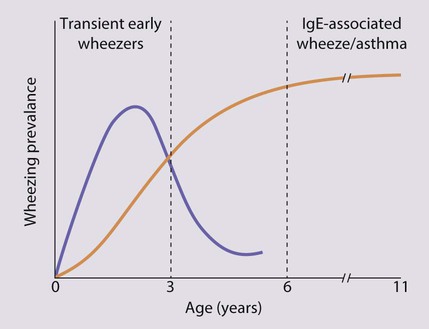

Diagnosing asthma in preschool children is often difficult. Approximately half of all children wheeze at some time during the first 3 years of life. In general, there are two patterns of wheezing (Fig. 16.9):

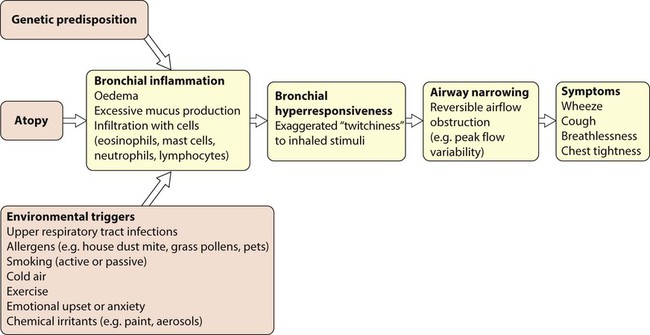

Pathophysiology of asthma

An outline of the pathophysiology of asthma is shown in Figure 16.10.

Up to 40% of all children are atopic (see Ch. 15). Siblings and parents have an increased risk of allergic diseases. The presence of one allergic condition increases the risk of another, e.g. half of children with allergic asthma have eczema at some time during their lives. The majority of asthma exacerbations are triggered by rhinovirus infection, and there is evidence that those with asthma have specific immune defects which increase their vulnerability to these viruses.

Clinical features

• Symptoms worse at night and in the early morning

• Symptoms that have triggers (e.g. exercise, pets, dust, cold air, emotions, laughter)

• Interval symptoms, i.e. symptoms between acute exacerbations

Once suspected, the pattern or phenotype should be further explored by asking:

• How frequent are the symptoms?

• What triggers the symptoms? Specifically, are sport and general activities affected by the asthma?

• How often is sleep disturbed by asthma?

• How severe are the interval symptoms between exacerbations?

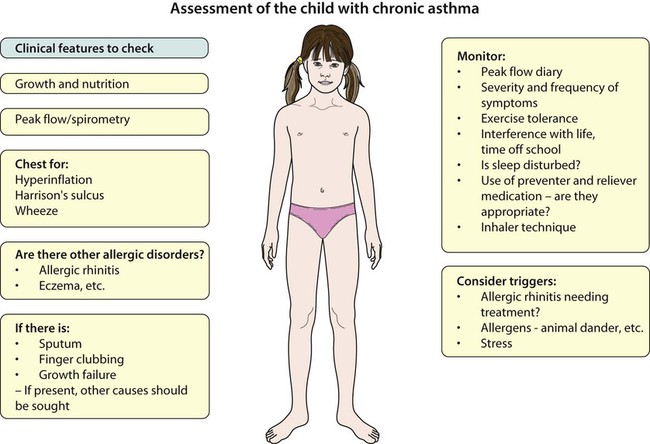

Examination of the chest is usually normal between attacks. In long-standing asthma there may be hyperinflation of the chest, generalised polyphonic expiratory wheeze and a prolonged expiratory phase. Onset of the disease in early childhood may result in Harrison sulci (Fig. 16.11). Evidence of eczema should be sought, as should examination of the nasal mucosa for allergic rhinitis. Growth should be plotted but is normal unless the asthma is extremely severe. The presence of a wet cough or sputum production, finger clubbing, or poor growth suggests a condition characterised by chronic infection such as cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis.

Management

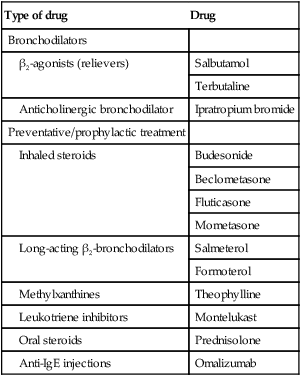

Medications used to treat children with asthma are shown in Table 16.2.

Table 16.2

| Type of drug | Drug |

| Bronchodilators | |

| β2-agonists (relievers) | Salbutamol |

| Terbutaline | |

| Anticholinergic bronchodilator | Ipratropium bromide |

| Preventative/prophylactic treatment | |

| Inhaled steroids | Budesonide |

| Beclometasone | |

| Fluticasone | |

| Mometasone | |

| Long-acting β2-bronchodilators | Salmeterol |

| Formoterol | |

| Methylxanthines | Theophylline |

| Leukotriene inhibitors | Montelukast |

| Oral steroids | Prednisolone |

| Anti-IgE injections | Omalizumab |

All are given by inhalation, except prednisolone, leukotriene modulators, theophylline preparations, which are by mouth, and omalizumab, which is by injection.

Other therapies

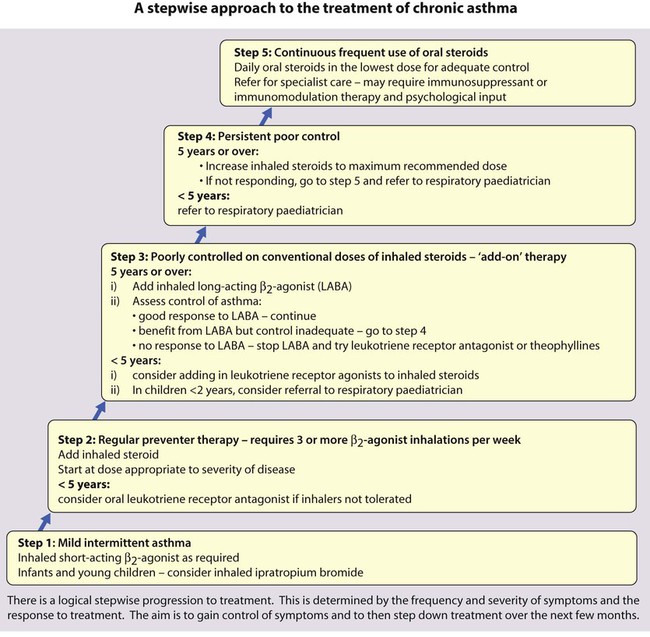

The British Guideline on Asthma Management uses a stepwise approach, starting treatment with the step most appropriate to the severity of the asthma. Treatment increases from step 1 (mild intermittent asthma) to step 5 (chronic severe asthma requiring continuous or frequent use of oral steroids), stepping down when control is good (Fig. 16.12).

Allergen avoidance and other non-pharmacological measures

Although asthma in many children is precipitated or worsened by specific allergens, complete avoidance of the allergen is difficult to achieve. The value of identifying such triggers by history or allergy testing is controversial. There is currently no conclusive evidence that allergen avoidance measures (such as removal of furry animals or using dust mite impermeable mattress covers) are beneficial, although they may be considered in selected cases. Allergen immunotherapy is effective for treating atopic asthma, but its use is limited by the risk of systemic allergic reactions associated with the treatment (see Ch. 15).

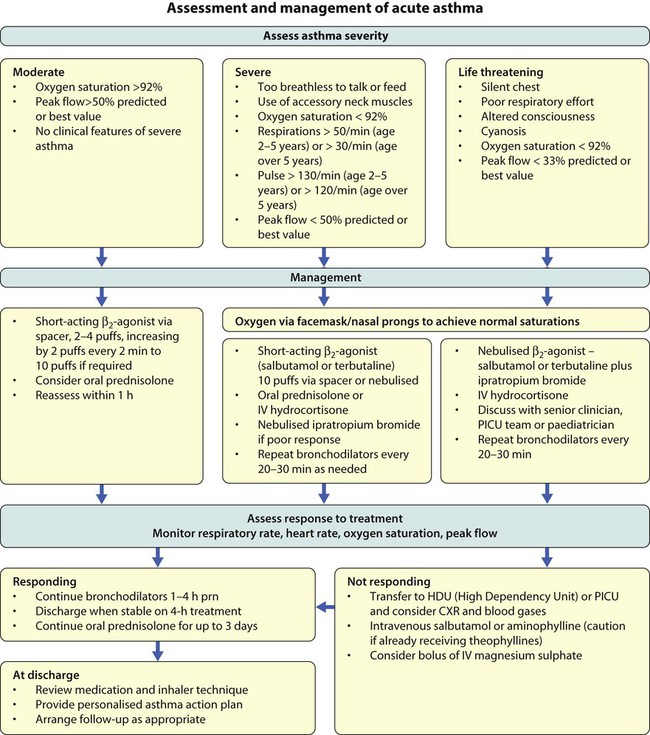

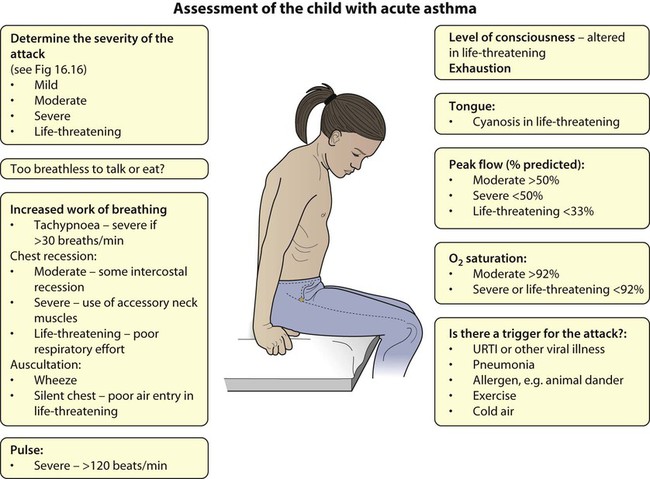

Acute asthma

Assessment

• Wheeze and tachypnoea (respiratory rate >50 breaths/min in children 2–5 years, >30 breaths/min in children ≥5 years) – but poor guide to severity

• Increasing tachycardia (>130 beats/min in children aged 2–5 years, >120 beats/min in children ≥5 years) – better guide to severity

• The use of accessory muscles and chest recession – also better guide to severity

• The presence of marked pulsus paradoxus (the difference between systolic pressure on inspiration and expiration) indicates moderate to severe asthma attack in children but is difficult to measure accurately and is therefore unreliable

• If breathlessness interferes with talking, the attack is severe

• Cyanosis, fatigue and drowsiness are late signs, indicating life-threatening asthma; this may be accompanied by a silent chest on auscultation as little air is being exchanged. This is an emergency as the child may be about to arrest.

• Arterial oxygen saturation should be measured with a pulse oximeter in all children presenting to hospital with acute asthma. Oxygen saturation <92% in air implies severe or life-threatening asthma

• Measurement of the peak expiratory flow rate should be routine in school-age children.

The features of a severe and life-threatening acute attack are shown in Figure 16.16.

Management

Management is summarised in Figure 16.16. As soon as the diagnosis has been made, the child should be given a β2-bronchodilator. For severe exacerbations, high-dose therapy should be given and repeated every 20–30 min. For moderate to severe asthma, 10 puffs of β2-bronchodilator should be given via a pressurised metered dose inhaler (pMDI) and large volume spacer. This is not only good treatment but also educates the child and parent in using the preferred devices they will have at home. For severe to life-threatening asthma, a β2-bronchodilator may need to be given via nebuliser driven by high-flow oxygen. The addition of nebulised ipratropium to the initial therapy in severe asthma is beneficial. Oxygen is given when there is any evidence of arterial oxygen desaturation, such as saturations of <92%. A short course (2–5 days) of oral prednisolone expedites the recovery from moderate or severe acute asthma.

Patient education

• When drugs should be used (regularly or ‘as required’)

• How to use the drug (inhaler technique)

• What each drug does (relief vs prevention)

• How often and how much can be used (frequency and dosage)

• What to do if asthma worsens (a personal asthma management plan is helpful: see the Appendix for an example).

Recurrent or persistent cough

Cough is the most common symptom of respiratory disease and indicates stimulation of nerve receptors in the pharynx, larynx, trachea or large bronchi. For most children, episodes of cough are due to upper respiratory tract infections caused by the common cold viruses and do not indicate the presence of a long-term or serious underlying respiratory disease. Cough appears persistent because of a series of respiratory tract infections, although some infections, such as pertussis, RSV and Mycoplasma infection, can cause a cough that persists for weeks or months. The challenge for the physician is to identify children with other, less common, clinically significant causes of recurrent or persistent cough (Box 16.3).

Chronic lung infection

Any child with a persistent cough that sounds ‘wet’ (i.e. sounds like there is excess sputum in the chest) or is productive should be investigated. The child may have bronchiectasis, permanent dilatation of the bronchi. Bronchiectasis may be generalised or restricted to a single lobe. Generalised bronchiectasis may be due to cystic fibrosis, primary ciliary dyskinesia, immunodeficiency or chronic aspiration. Cystic fibrosis is considered separately below. Focal bronchiectasis is due to previous severe pneumonia, congenital lung abnormality or obstruction by a foreign body (see Case History 16.2).

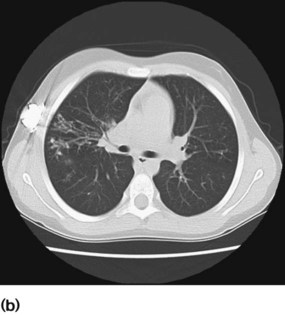

A plain chest X-ray may show gross bronchiectasis, but will often not identify it. Bronchiectasis is best identified on a CT scan of the chest (Fig. 16.17a,b). To investigate focal disease bronchoscopy is usually indicated to exclude a structural cause.

Cystic fibrosis

Epidemiology, genetics and basic defect

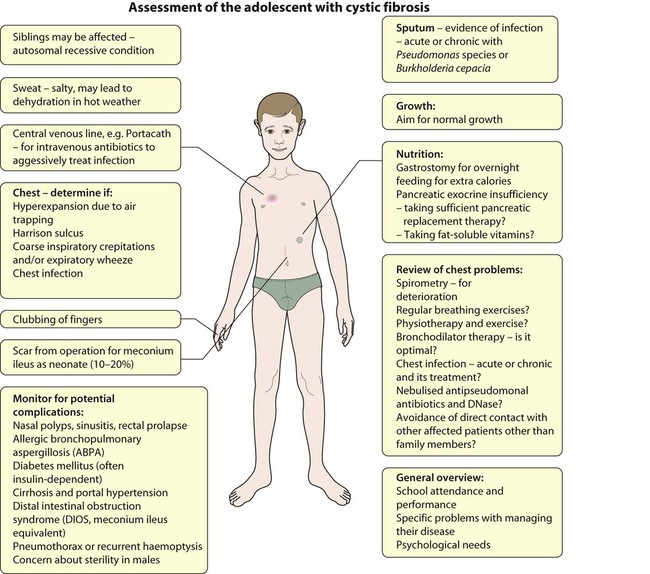

Clinical features

In the UK, screening of newborns is now performed as part of the heel-prick bloodspot biochemical screen (Guthrie test). The majority of children with CF are identified by screening; however, children may still present clinically with recurrent chest infections, poor growth or malabsorption (Box 16.4). Chronic infection with specific bacteria – initially Staphylococcus aureus and Haemophilus influenzae and subsequently with Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Burkholderia species results from viscid mucus in the smaller airways of the lungs. This leads to damage of the bronchial wall, bronchiectasis and abscess formation (Fig. 16.19). The child has a persistent, loose cough, productive of purulent sputum. On examination there is hyperinflation of the chest due to air trapping, coarse inspiratory crepitations and/or expiratory wheeze. With established disease, there is finger clubbing. Ultimately, 95% die of respiratory failure.

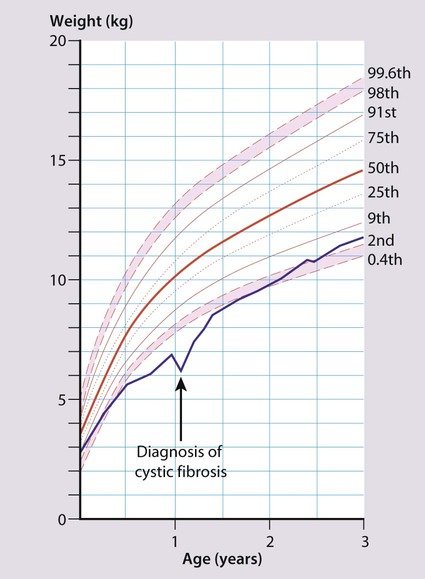

Over 90% of children with CF have pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (lipase, amylase and proteases), resulting in maldigestion and malabsorption. Untreated, this leads to failure to thrive (Fig. 16.20) and passing frequent large, pale, very offensive and greasy stools (steatorrhoea). Pancreatic insufficiency can be diagnosed by demonstrating low elastase in faeces.

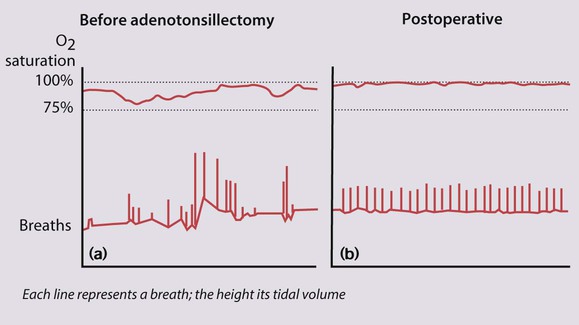

Sleep-related breathing disorders

In cases due to adenotonsillar hypertrophy, adenotonsillectomy is usually curative (Fig. 16.21a,b). Overnight oximetry should be performed prior to surgery for obstructive sleep apnoea to identify severe hypoxaemia, which may increase the risk of perioperative complications. If it persists despite adenotonsillectomy, polysomnography should be performed in a specialist centre. Nasal or facemask continuous positive pressure ventilation (CPAP) or bi-level positive airway pressure (BIPAP) may be required at night.

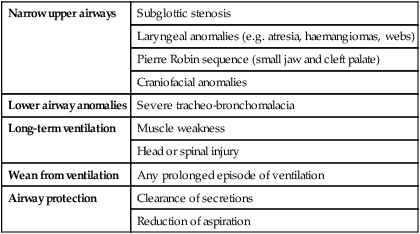

Tracheostomy

The number of children of all ages with a tracheostomy is increasing. Indications are listed in Table 16.3.

Table 16.3

Some indications for tracheostomy in children

| Narrow upper airways | Subglottic stenosis |

| Laryngeal anomalies (e.g. atresia, haemangiomas, webs) | |

| Pierre Robin sequence (small jaw and cleft palate) | |

| Craniofacial anomalies | |

| Lower airway anomalies | Severe tracheo-bronchomalacia |

| Long-term ventilation | Muscle weakness |

| Head or spinal injury | |

| Wean from ventilation | Any prolonged episode of ventilation |

| Airway protection | Clearance of secretions |

| Reduction of aspiration |

Long-term ventilation

An increasing number of children are receiving long-term respiratory support. Preterm infants with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia (chronic lung disease) may require additional oxygen for many months, and may also require respiratory support with CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) via nasal prongs or nasal mask. Children with muscle weakness from Duchenne muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, congenital muscular dystrophy and other rare conditions are increasingly offered long-term ventilatory support. They experience not only hypoxia but also significant hypercapnia due to hypoventilation. This requires bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP), which can be delivered non-invasively by a nasal mask or full facemask (Fig. 16.22). In some cases BiPAP may need to be delivered via a tracheostomy (Fig. 16.23). In Duchenne muscular dystrophy and some other conditions causing muscle weakness, non-invasive ventilation at night provides additional quality years of life. This service can often be provided at home, with considerable specialist community support. With progressive neurological disorders, difficult ethical decisions need to be made about admission for intensive care and initiation of long-term full ventilation.