11 Respiratory Disorders

Acute breathlessness

The systems involved would most probably be cardiac or respiratory. You go through the list in Box 11.1 (p. 346) as you walk to the ward.

Initial assessment

Then make a full cardiac and respiratory examination. Is there any evidence of DVT?

Upper airways obstruction

Diagnosis: Upper airways obstruction

Fortunately, the emergency crew recognised the problem and tried to clear the airway. There was no improvement so the Heimlich manoeuvre was performed and a large bone was expelled with immediate relief of the man’s respiratory distress. He was taken to A&E for assessment but discharged after 2 hours.

Remember

The Heimlich manoeuvre is used to expel an inhaled foreign body:

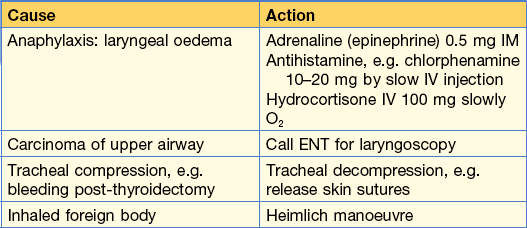

Other causes of upper airway obstruction are shown in Table 11.1, all of which require emergency management, which is also shown.

Cough

Acute cough

• Inhalation of direct irritants, e.g. smoke, chlorine gas, ozone and other air pollutants.

• In the asthmatic, inhalation of specific allergen, e.g. pollen or non-specific low-concentration irritants, e.g. perfume, tobacco fumes.

• Upper and lower respiratory tract infections (yellow/green sputum).

Chronic cough

• Large airway obstruction, e.g. carcinoma of bronchus or inhaled foreign body (Note: peanuts and other inhaled food will not be radio-dense).

• Persistent bronchial inflammation, e.g. asthma, bronchiectasis, COPD, smoking.

• Persistent infection, e.g. tuberculosis, lung abscess.

• Interstitial lung disease, e.g. pulmonary fibrosis, asbestosis.

• Raised left atrial pressure, e.g. mitral stenosis, left ventricular failure.

Breathlessness and wheeze

Asthma causes breathlessness, cough and wheeze. However, all that wheezes is not asthma.

Differential diagnosis of asthma:

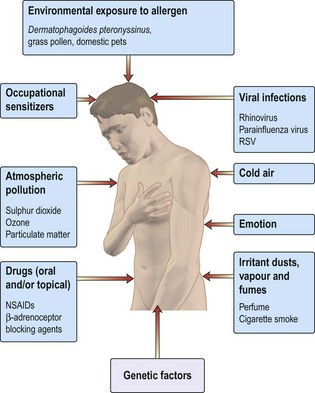

Figure 11.1 shows causes and triggers of asthma.

How would you manage this patient in A&E?

Immediate management should be:

• Reassurance that treatment will be effective

• Oxygen 40–60% (Keep SaO2 > 90%)

• Nebulised short acting β2 agonist (SAB), e.g. salbutamol 5 mg or terbutaline 10 mg) with oxygen. (NB only 10% of drug reaches the lungs)

• Arterial blood gases (ABGs):

• PEFR 4-hourly. Note: performing PEFR might be distressing for patient: do not demand unnecessary repeat testing

30 min later there has been no significant improvement in her breathlessness and PEFR. What would you do next?

• Continue with nebulised β2 agonist, now with added ipratropium (500 µg). Repeat every 30 min if necessary.

• Intravenous aminophylline infusion can be used if patient does not respond to repeated nebulisation with β2 agonist and ipratropium. However, do not use this if oral aminophylline has been taken.

There is now improvement in PEFR and breathlessness with nebulised β2 agonist and ipratropium. What treatment should be offered to her now?

24–48 h before discharge

• Add inhaled corticosteroids, e.g. beclometasone, to oral steroids.

• Replace nebulised bronchodilators with inhalers.

• Introduce long-acting inhaled β2 agonists, e.g. salmeterol.

• Check inhaler technique (? might need spacer).

• Determine the cause of this attack (non-compliance, infection, allergen exposure).

Hyperventilation

Haemoptysis

Case history

Coughing up blood is a dramatic symptom and can be frightening to patients and their families.

Colour of blood – this can differ with different causes

• Pink frothy sputum: pulmonary oedema.

• Make sure it is not haematemesis, which would be suggested by:

Enquire about epistaxis, which may cause confusion. Blood-stained saliva suggests bleeding from gums.

Common conditions presenting with haemoptysis

Management of this case

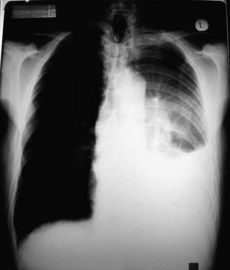

A chest X-ray was taken (Fig. 11.2 and Information box) which showed a pleural effusion and a hilar mass. The pleural effusion was aspirated and sent for cytology. A pleural biopsy was taken under ultrasound control and showed no evidence of malignancy on histology.

The patient was referred to the multidisciplinary team for discussion of treatment options.

Management of massive haemoptysis

• Monitor: oxygen saturation with oximetry, blood pressure and pulse rate.

• Perform CXR. Exclude coagulation defects.

• Endotracheal intubation and suction might be required.

• Urgent bronchoscopy by an experienced doctor is sometimes required.

• A cuffed tube can be employed to protect the unaffected lung. It is inserted into the bronchus via a bronchoscope.

• Bronchial artery embolisation is highly effective if the bleeding vessel can be identified.

Chest pain

• Exercise-induced central chest pain is usually cardiac in origin.

• Rest pain might be: cardiac, pleuritic, musculoskeletal, nerve root irritation, oesophageal, mediastinal or referred pain from abdomen.

• Lung diseases only cause pain if the pleura, mediastinum, intercostal nerves or bones are involved.

Is it cardiac pain?

Is it musculoskeletal?

• Muscles: Bornholm’s disease. Follows an upper respiratory tract infection; a low-grade fever can occur. Ache in muscles. Might be tender. Definite cases rare.

• Costochondral junction: Tietze’s disease; local pain on pressure over junctions. Responds to NSAIDs.

Respiratory failure

In respiratory failure arterial blood gas sampling is necessary to

• Identify type, i.e. alveolar hypo- or hyperventilation

• Appreciate the degree of compensation (i.e. the chronicity of the condition)

• A coexisting metabolic acidosis commonly causes confusion and can be recognised by the base excess value (see below).

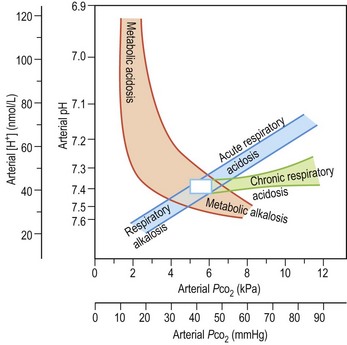

Summary of acid–base changes (Fig. 11.3)

In a respiratory acidosis

Examples: exacerbation of COPD, flail chest injury, Guillain–Barré syndrome.

Common ABG abnormalities

Life-threatening asthma

Supplemental O2 is being provided (note the high PaO2). There is a metabolic acidosis (note the pH and BE) as a result of metabolic demands exceeding O2 delivery and producing a lactic acidosis. Airflow limitation limits the normal respiratory compensation to this profound acidosis.

Acute or chronic respiratory failure in a patient with COPD

Acute or chronic respiratory acidosis exacerbated by a high FiO2 using variable performance mask (40–60% O2) (note high PaO2 and PaCO2). The high HCO3 results from renal compensation. The patient was changed to 28% oxygen.

Severe pneumonia (FiO2 60%)

Despite high FiO2 this patient is hypoxaemic because of ventilation: perfusion mismatch. The profound hypoxia despite oxygen and the associated metabolic acidosis indicate the need for urgent intubation and IPPV and are a reflection of circulatory failure resulting from septic shock.

How do I recognise impending respiratory arrest?

• Tachypnoea, respiratory rate > 30

• Sympathetic activation: pale and sweaty, agitation, confusion

• Progressive increase in PaCO2 or fall in PaO2

• Rapid desaturation on disconnection from O2, e.g. when drinking or coughing.

Evaluation is often at the ‘end of the bed’: is the patient getting tired? Be sensitive to subtle changes or a failure to improve.

Treating the cause

• Individual causes will require different actions: for instance, an intercostal drain for a tension pneumothorax or large pleural effusion (see p. 364).

• In neurological coma, intubation might be necessary for airway protection or to manage raised intracranial pressure by hyperventilation.

• Drug-induced respiratory failure can be confirmed by a therapeutic trial with a specific antidote, i.e. a bolus injection of naloxone for opiates and flumazanil for benzodiazepines. Infusions will be required if a positive response is obtained as antidotes have short half life.

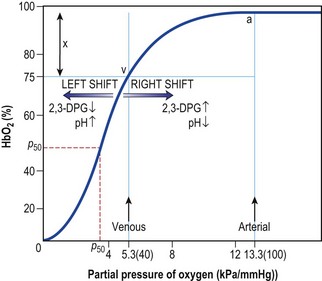

• Oxygen supplementation should be aimed at raising the PaO2 to beyond the steep part of the oxygen dissociation curve (Fig. 11.4). Very high PaO2 values are unnecessary but controlled O2 therapy via a fixed performance mask is only necessary in chronic respiratory failure resulting from COPD.

What do these blood gases mean?

The initial treatment in A&E was:

• Nebulised bronchodilators (salbutamol 5 mg nebulised + ipratropium bromide 500 µg).

• IV amoxicillin (erythromycin if patient penicillin allergic).

• IV steroids (this is conventional treatment but there is limited evidence for effectiveness). Hydrocortisone 100 mg × 3 daily.

• Encouragement to clear secretions including sitting patient up and the attention of the physiotherapist.

• CXR to exclude pneumothorax or demonstrate associated pneumonia.

Repeat ABGs were requested: pH 7.20, PaO2 6.5, PaCO2 12.5, HCO3 30.

COPD – acute exacerbation

It was decided not to admit him to hospital because:

• He was able to cope at home with aid of his wife

• He was not cyanosed: oximetry showed SaO2 97%

• His general condition was good and he had a normal level of consciousness.

He was discharged home with:

• Amoxicillin 500 mg × 3 daily for 1 week

• Prednisolone 30 mg daily for 2 weeks

• Advice to increase his inhaled bronchodilators to salbutamol four puffs, 4-hourly via a spacer

Key points

• The patient did not need admission because:

• Antibiotic was broad spectrum and, in particular, covered the majority of Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae organisms (the most common causes of acute exacerbation). Erythromycin was unnecessary because Mycoplasma was unlikely.

• Oral steroids were used as adjunct to antibiotics because the patient was already on inhaled steroids and possibly had a degree of steroid responsiveness. This is conventional treatment but there is limited evidence to support it.

• Patient was given a spacer (and shown how to use it) in order to increase the lung deposition of aerosol.

• Salbutamol dose was increased and given 4-hourly because the effect lasts only 4–6 h and is partly dependent on dose.

• Follow-up at chest clinic because patient had moderately severe COPD and had never been assessed:

However, the patient’s doctor, when seeing the patient 1 week later, cancelled the outpatient appointment believing it unnecessary. He wrote to the chest physician saying that he was able to manage the patient himself. He had a spirometer in the surgery and when well the patient had an FEV1 of > 50% predicated normal. Furthermore, the doctor said that the patient:

• Had only moderately severe COPD

• No respiratory failure and did not need oxygen

The patient’s doctor was arranging to perform bronchodilator tests himself using a spirometer and checking the response to both salbutamol and ipratropium inhalers. He would arrange vaccination.

Box 11.1

Causes of breathlessness

Prognosis of COPD

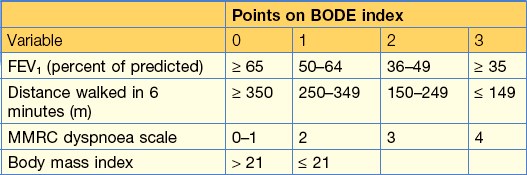

A patient with a BODE index (Table 11.2) of 0–2 has a mortality rate of 10%; one with a BODE index of 7–10, a mortality rate of 80% at 4 years.

Table 11.2 BODE index (Body mass index, degree of airflow Obstruction, Dyspnoea and Exercise capacity)

Case history (2)

On examination

• Showed signs of respiratory failure: drowsy and cyanosed, CO2 flap

• Pulse 130/min; atrial fibrillation; BP 100/60

• Cor pulmonale with tricuspid regurgitation:

• Respiratory rate 30, shallow breaths using accessory muscles of respiration, generalised wheezing and bilateral basal crackles. Investigations showed:

• Arterial blood gases: pH 7.32, PaO2 5.6, pCO2 8.2 on air

• FBC Hb 178 g/L, Hct 54%, WBC 12 300

• Urea 9.0, K+ 3.5, creatinine 102

• Chest X-ray: overinflated lungs with prominent pulmonary arteries (indicating pulmonary hypertension) and normal-sized heart.

Key points

• Patient in respiratory failure with raised PaCO2: give oxygen via fixed performance mask 24, initially increasing to 28 or 35% if no rise in PaCO2.

• Cor pulmonale (right heart failure secondary to lung disease) is difficult to improve while the patient remains hypoxic.

• Atrial fibrillation may only be secondary to hypoxaemia and might revert to sinus rhythm when PaO2 improves.

Immediate treatment

• Oxygen 28% via Venturi mask and repeat ABGs.

• Sit patient upright to help breathing.

• Give nebulised bronchodilators:

• Chest physiotherapy to help sputum expectoration.

• Amoxicillin 500 mg × 3 daily IV until condition improves and then oral for 1 week in total.

• IV hydrocortisone 100 mg × 3 daily until patient improves and then oral prednisolone 20 to 30 mg daily for 2 weeks. If not on oral theophyllines, start aminophylline infusion.

• Monitor oximetry + mental state, respiratory rate and pulse until improvement. Daily weights.

There was no improvement

• Doxapram as a respiratory stimulant (1.5–4 mg/min infusion) which sometimes helps.

• Non-invasive intermittent positive pressure ventilation (NIV) (see p. 343). The best technique is using a tight-fitting facial mask to deliver bilevel positive airway pressure ventilation support (BiPAP).

Key points

• Oxygen should be prescribed on treatment sheet and given continuously, not ‘as required’.

• Management of oxygen is the most helpful and difficult component of treatment.

• Although oxygen by a Venturi mask gives a known concentration it is uncomfortable and claustrophobic. It has to be removed to eat, talk and cough and for nebulised treatment.

• Oxygen by nasal spectacles is more comfortable and can be kept on continuously.

• Nasal oxygen gives variable FiO2 depending on pattern of breathing and flow rate between 24% and 35%. It worked on this patient but in many patients with COPD, a 24% oxygen via a mask is preferable when PaCO2 > 8.0 kPa.

• It takes 30–40 min to equilibrate blood gases with any change in FiO2 and blood gases should not be checked earlier.

• It is unnecessary to get the PaO2 normal: aim to get it at the top of the steep slope of the oxygen saturation curve (see Fig. 11.3).

• If PaO2 is > 7.5 kPa, a small fall in PaO2 has little effect on O2 saturation: this is safe.

• If PaO2 is 6.5 or less, a small fall produces a dangerous fall in SaO2. Note: the sigmoid shape of oxygen dissociation curve (see p. 342).

• Increasing the inspired oxygen may cause a small rise in PaCO2 (mostly because of relaxation of hypoxic vasoconstriction in relatively poorly ventilated alveoli). A pH change of < 0.1 or PaCO2 < 1 kPa is not significant, so do not reduce or remove the oxygen.

• If, on increasing FiO2, this patient had not clinically improved and ABGs showed PaO2 6.8, PaCO2 12.0:

Key points

Pneumonia

This is the typical history of community-acquired pneumonia.(CAP).

Likely infecting organisms

• Streptococcus pneumoniae: the most likely cause (35–80% of cases)

• Haemophilus influenzae: especially in smokers with COPD

How ill is this patient?

The following CURB-65 criteria indicate the severity of CAP.

CURB-65 Criteria for the diagnosis of severe community-acquired pneumonia

Progress.

This patient was young, previously fit, not breathless or shocked. The chest X-ray (Fig. 11.5) showed a left lower lobe pneumonia and the WBC was 11 500. Normal urea. PaO2 10.5 kPa.

This pneumonia is not severe on the CURB criteria.

The patient was treated with oral antibiotics and was discharged in 24 hours (see Antibiotic choices, p. 353).

Investigations show

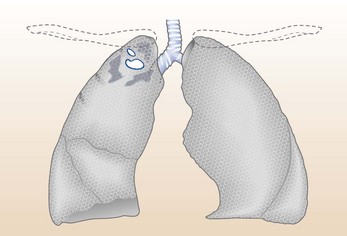

This is a high-risk case. He has influenza and a superinfection with Staphylococcus aureus causing severe community-acquired pneumonia with early abscess formation (ring opacities on the CXR). He needs:

• Rehydration: intravenous fluid

• Intravenous antibiotics: see Antibiotics, below – severe CAP

• Pulse oximetry: give O2 to try to keep O2 sat > 90%

• Nursing where he can be easily observed or in an HDU (hourly BP, pulse, RR)

• To be watched for respiratory failure: IPPV might be needed

Antibiotic choices for CAP

Consult your Hospital Formulary or select from below:

Uncomplicated mild community-acquired pneumonia

Q fever and psittacosis

Progress.

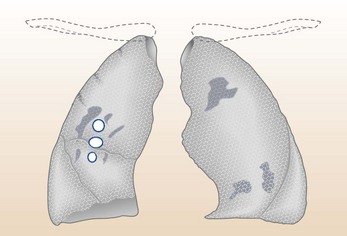

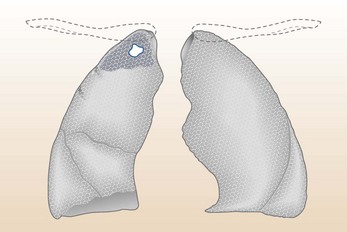

You should think this patient may have HIV infection with a Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia because of country of origin, 6-month history of illness, lymphadenopathy, low white cell count and appearance on CXR (Fig. 11.7).

On investigation, the CXR had:

Remember

• Heavy alcohol users: inhalation pneumonia (Gram-negative organisms)

• Drug users: ‘dirty’ needles and syringes, infected emboli to lungs (Staphylococcus aureus)

• Tuberculosis: a sputum smear for AFB is quick and easy to do. Can coexist with other pneumonias

These latter two are seen in immunocompromised patients, for example with:

Treatment should start in this patient for pneumocystis jiroveci

• High-dose IV co-trimoxazole.

• Add IV cefuroxime and erythromycin if in doubt as to cause of the pneumonia.

• May need high-dose steroids IV if deteriorates.

Lung abscess

Case history

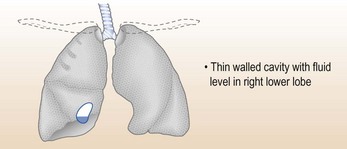

On examination he had a temperature of 39.8°C, a few crackles at the right base but no other respiratory signs. A chest X-ray (Fig 11.8) shows a cavity.

Tuberculosis

Progress.

Investigations

A provisional differential diagnosis was made of:

Urgent sputum was sent for staining with auramine-phenol fluorescent test and culture + sensitivities for AFB (if no organisms found send at least three more good sputum specimens). TB bacilli were found in the third sputum specimen (smear +ve).

Management

• Isolate patient as smear +ve.

• Treat delirium tremens (see p. 525). Note: always also give thiamine.

• Start anti-TB therapy (see below) as soon as possible.

• Notify patient to infection control and contact TB health visitor to do contact tracing.

Further history

Progress and action

This patient was isolated in a side room (smear +ve).

• Treatment for TB given (see below).

• TB is a notifiable disease in the UK and allows contact tracing to be initiated.

Key points

• Many patients do not volunteer their HIV status.

• You must indicate that Mycobacterium TB is a possibility when requesting sputum examination.

• Atypical radiological changes are common in TB in the immunocompromised.

• Both Mycobacterium intracellulare avium and Mycobacterium tuberculosis can be isolated from stool and blood.

• A patient from Africa with pneumonia should be admitted to a side room until TB has been excluded.

• The risk of TB developing in those infected (i.e. disease reactivation) in HIV increases when CD count < 200.

Treatment – drug therapy in tuberculosis

• Rifampicin: if body weight < 50 kg, 450 mg daily; if body weight ≥ 50 kg, 600 mg daily.

• Pyrazinamide: if body weight < 50 kg, 1.5 g daily; if body weight ≥ 50, 2 g daily.

• Ethambutol: 15 mg/kg (test visual acuity before treatment).

• Give all drugs together once daily with breakfast.

• All four drugs for 2 months followed by rifampicin and isoniazid for 4 months (having checked the sensitivities).

NB: This patient may have multi-resistant TB (MRTB).

Pleural effusion

What do you do next?

A syringe with a 21 G needle was used to obtain 20 mL of fluid. This was sent to the laboratory for:

Result

What next?

• The patient has inoperable lung cancer (malignant cells in fluid).

• Treatment should be discussed at an MDT meeting concentrating on relieving symptoms and discussion of possible chemotherapy.

Drain the effusion (following explanation and consent) with an intercostal drain placed ideally over the top of the diaphragm.

Progress.

Case history (2)

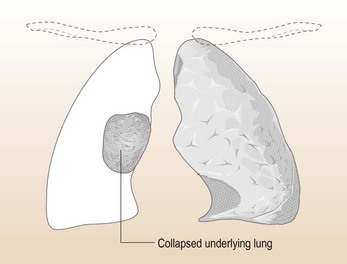

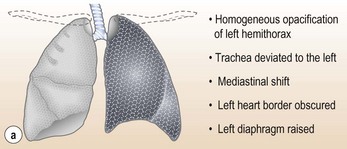

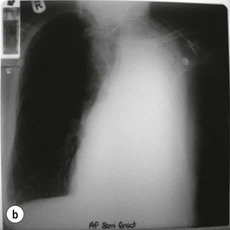

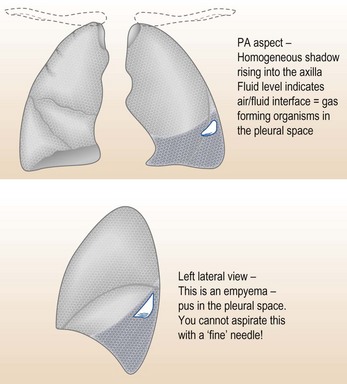

A 43-year-old woman developed increasing breathlessness and malaise after being treated for pneumonia with oral cefalexin 2 weeks previously. She was febrile with a temperature of 39°C, flushed and anorexic with signs of a left pleural effusion. A pleural tap produced cloudy, infected fluid (an empyema). A diagram of the CXR appearances is shown in Figure 11.11.

What should you do?

• Drain the fluid by placing an intercostal drain.

• Start antibiotics (after taking blood and fluid cultures). This should cover both aerobic and anaerobic organisms: cefuroxime 1 g 6-hourly IV, metronidazole 500 mg IV 8-hourly for 5 days, followed by oral cefaclor and metronidazole for 2–4 weeks.

• Consult chest physician/surgeon early if drainage is incomplete. Decortication of the lung or a rib resection and wide-bore drain might be needed.

• Bronchoscopy should be performed to exclude bronchial obstruction. CT scanning is helpful to assess presence of underlying lung abscess.

Pulmonary embolism (and deep vein thrombosis)

The diagnosis of pulmonary embolism can be difficult for a number of reasons:

• It is often not present when thought of

• It is present when not thought of

Other common clinical scenarios caused by pulmonary embolisms you will meet are:

• Acute minor pulmonary infarction producing pleuritic chest pain and possibly haemoptysis.

• Episodic non-specific symptoms in the postoperative patient (such as palpitations and anxiety attacks) possibly followed by a cardiac arrest when at toilet.

• Chronic minor thrombo-embolism leading to established pulmonary hypertension.

Simple investigations.

These are usually only helpful when the diagnosis is clinically obvious.

Invasive investigations

• CT. Contrast-enhanced, multi-detector CT angiograms (CTAs) have a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 96%, with a positive predictive value of 92% (higher with 64-multislice scanners).

• Radionuclide ventilation/perfusion scanning ( scan). This is a good test after measurement of D-dimers. It demonstrates ventilation/perfusion defects, i.e. areas of ventilated lung with perfusion defects. Pulmonary 99mtechnetium scintigraphy demonstrates the under-perfused areas, while a scintigram, performed after inhalation of radioactive xenon, shows no ventilatory defect. A matched defect may, however, arise with a PE that causes an infarct, or with emphysematous bullae. This test is therefore conventionally reported as a probability (low, medium or high) of PE and should be interpreted in the context of the history, examination and other investigations.

scan). This is a good test after measurement of D-dimers. It demonstrates ventilation/perfusion defects, i.e. areas of ventilated lung with perfusion defects. Pulmonary 99mtechnetium scintigraphy demonstrates the under-perfused areas, while a scintigram, performed after inhalation of radioactive xenon, shows no ventilatory defect. A matched defect may, however, arise with a PE that causes an infarct, or with emphysematous bullae. This test is therefore conventionally reported as a probability (low, medium or high) of PE and should be interpreted in the context of the history, examination and other investigations.

• MRI. This gives similar results to CT and is used if CTA is contraindicated.

The echocardiogram can be very useful in the diagnosis of massive PEs but is of limited value otherwise:

Treatment

Supportive therapy with oxygen and analgesia should be given.

• Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is licensed for use in DVT and patients with minor PE, e.g. pulmonary infarction can be treated without admission if the necessary organisation is available in the community. Use unfractionated heparin if rapid reversal is required.

• These treatments only prevent further clot formation.

• Warfarin is started and heparin discontinued once INR is therapeutic (INR 2–3).

• 6 months’ warfarin is adequate therapy and 6 weeks might be sufficient in patients with surgery as the provoking factor and no underlying coagulopathy. Anti-thrombin agents, e.g. dabigatram, are being used in place of heparin and warfarin.

• Thrombolytic therapy is used for clot lysis in major pulmonary embolism. There is increasing experience of thrombolytic therapy. Although good evidence of reduced mortality is lacking, there is faster and more complete resolution of echocardiographic abnormalities or  defects:

defects:

Pneumothorax

Case history (1)

Management of pneumothorax

This man was symptomatic and had a moderate-sized pneumothorax. Aspiration is the first choice. Explain and obtain consent:

Further management

• Patient was discharged home after observation and some resolution on CXR, taking his discharge X-ray.

• Instructed not to fly for 6 weeks or go deep-sea diving.

• Given follow-up appointment in chest clinic for 1 week.

• Instructed to re-attend (bringing X-ray) if he became breathless.

Management

• Controlled oxygen as per blood gases

• Urgent insertion of cannula followed by insertion of intercostal tube.

Information

Management of intercostal tube

Insertion of tube:

• Explain and reassure patient throughout. Obtain consent

• Premedicate with opiate and atropine to prevent reflex bradycardia, particularly if patient anxious, in patients with pre-existing lung disease

• Double-check the site of pneumothorax

• Site: 4–6th intercostal space in anterior axillary line – mark with pen + position patient supine with head at 30° and arm abducted to 90°

• Drain 10–14 FG (adult). Check assembly and tight connection and that underwater seal is ready

Insertion of drain:

• 1 to 2 cm incision in skin and subcutaneous fat

• Insert two horizontal sutures across incision (leave loose for subsequent sealing of wound on drain site)

• Wide tract made through intercostal muscles down to and through pleura by blunt dissection with forceps (not sharp trocar)

• Insert tube using Seldinger technique and drain assembly without force

• Withdraw metal needle 5 cm and advance tube in apical direction

• Remove metal needle and connect tube to underwater seal

• Secure tube firmly with one or two sutures (1 loop through skin and 4 times round tube). Purse string suturing is no longer advised as it leaves unsightly scarring

• Loop tube and secure to skin with plaster (Note: no kinks)

Removal of tube:

• Leave tube draining until no further bubbling + then re-X-ray (X-ray earlier if in doubt about site or efficacy of tube). Note: if level not swinging tube blocked. Clear or replace if lung not re-expanded

• Some patients need premedication for tube removal

• Remove holding suture and withdraw while patient breath-holds in expiration

• Seal wound with one of original sutures

• Observe overnight and if no recurrence of pneumothorax (clinical and X-ray) discharge with Chest Clinic appointment in 7 to 10 days. Patient keeps last X-ray to bring to appointment or to A&E in emergency.

Carcinoma of the bronchus

What is the most likely diagnosis and why?

What are the diagnostic investigations?

If histological diagnosis is not made on bronchoscopy, CT-guided percutaneous needle biopsy should be performed.

Radiological manifestations of lung cancer

• Its effect on neighbouring tissues:

Other presentations are:

Differential diagnosis

Pneumonia

• Presence of lobar collapse on chest X-ray

• Irregular margins of the lung shadow representing consolidation

• Absence of constitutional symptoms associated with pneumonia

• Symptoms such as haemoptysis and weight loss prior to the development of pneumonia, especially in middle-aged or elderly smoker.

Patient should be investigated for lung cancer if:

Management of major complications

Management of patients with neutropenia following chemotherapy

Recommended antibiotic regimes

• IV gentamicin 3–5 mg/kg IV once a day (monitor trough levels) and a ureidopenicillin (Piperacillin with Tazobactam 4.5 g every 6 hours).

• In presence of severe renal insufficiency, replace gentamicin with IV ceftazidime 1–2 g × 3 daily or ciprofloxacin 400 mg × 2 daily.

• Continue antibiotics for 5 days or until white cell counts are in normal range and symptoms have remitted.

If no improvement after 48 to 72 h of antibiotic therapy

Indications for Filgrastim (G-CSF) – specialist use only

• Absolute neutrophil count: 0.2

• Persistent neutropenia (< 1.0 for more than 48 h)

• Stop therapy when absolute neutrophil count is 1.5 or more.

Sarcoidosis

Is this erythema nodosum (EN)?

From the description this sounds very likely and you ask the doctor to send the patient up to outpatients when you will arrange for a CXR to be performed (Fig. 11.17).

What is sarcoidosis?

The chances of further trouble are negligible.

• Skin lesions: 10% of cases. Apart from EN, a chilblain-like lesion (lupus pernio) and nodules are seen.

• Eye involvement: 5% of cases. Anterior uveitis (misting of vision, pain, red eye) is common. Posterior uveitis may present with a progressive loss of vision. Conjunctivitis and retinal lesions are seen. Asymptomatic uveitis may be found in 25% of patients.

• Metabolic hypercalcaemia: found in 10% but it is rarely severe.

• CNS involvement: is rare (2%) but can lead to severe neurological disease.

• Bone and joint involvement: arthralgia without EN is seen in 5% of cases.

• Cardiac involvement: is rare (3%) clinically, although seen in 20% of post-mortems. Ventricular arrhythmias, conduction defects and cardiomyopathy with CCF are seen. The serum ACE is insensitive in cardiac sarcoid and echocardiography should be performed in chronic sarcoidosis.

Your consultant does say that the above list is comprehensive but fortunately the conditions are rare.

Progress.

The next morning you return with your consultant, having obtained the patient’s old notes.

• Reduced total lung capacity (restrictive ventilatory capacity)

• Impaired gas transfer (TLCO)

• Serum ACE level: this had been done a few years back and was found to be raised.

Review of his past treatment shows that he has been given steroids on many occasions and azathioprine and methotrexate as steroid-sparing agents.

scan revealed the typical multiple patchy perfusion abnormalities of recurrent minor pulmonary embolism, which explains her 3-month history of breathlessness. The scan has remained abnormal and she has continued to be breathless. Leiden factor V deficiency was discovered and the oral contraceptive stopped. She has been advised to remain on life-long warfarin.

scan revealed the typical multiple patchy perfusion abnormalities of recurrent minor pulmonary embolism, which explains her 3-month history of breathlessness. The scan has remained abnormal and she has continued to be breathless. Leiden factor V deficiency was discovered and the oral contraceptive stopped. She has been advised to remain on life-long warfarin.