Chapter 69 Respiratory Conditions

ASTHMA

ETIOLOGY

What Are the Common Clinical Patterns of Asthma?

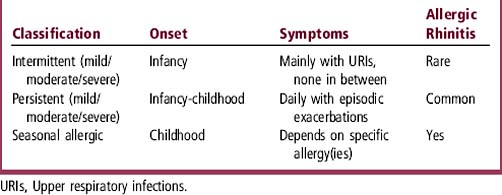

Intermittent asthma is the most common pattern of asthma in children. Other patterns are persistent asthma and seasonal allergic asthma (Table 69-1). Although the National Asthma guidelines classify intermittent asthma as “mild,” symptoms during an exacerbation of intermittent asthma in a child may be severe enough to warrant hospitalization. Therefore, intermittent asthma in childhood is best considered to have a range of severity from mild to severe. Young children commonly have a pattern of frequent, recurrent exacerbations of asthma, usually triggered by viral upper respiratory infections (URIs). Approximately 15% of children have 12 or more URIs a year, each of which may trigger an acute asthma exacerbation. This translates to approximately one URI-triggered asthma “attack” every 3 to 4 weeks for many young asthmatics during the fall and winter viral infection season. The frequency of URI-induced exacerbations makes the distinction between intermittent and persistent asthma difficult in infants and toddlers.

What Are Common Triggers for Childhood Asthma?

Table 69-2 shows common triggers for asthma and their usual timing. All patterns of asthma can be exacerbated by viral illnesses. Up to 85% of acute exacerbations that require emergency department (ED) or hospital care are associated with viral illnesses.

| Cause | Season |

|---|---|

| Viral illness | Fall–spring |

| Exercise | With exercise, year-round |

| Irritant (smoke, perfume, etc.) | With exposure, year-round |

| Cold air | Winter |

| Allergies | |

|---|---|

| Molds | Spring and fall |

| Pollens | Spring–summer |

| Cats/dogs | Year-round |

| Grasses | Spring–summer |

| Dust mites | Year-round |

| Cockroaches | Year-round |

EVALUATION

What History and Examination Findings Are Important?

The asthmatic child or adolescent often comes to attention because of cough (see Chapter 25). Table 69-3 shows important history and physical findings in asthma. Asthma diagnosis is primarily made from the patient’s history and response to medications.

| History | Physical Examination |

|---|---|

| Response to albuterol (immediate) | Increased respiratory rate |

| Response to oral steroids (1-3 days) | Expiratory wheezing |

| Symptoms between exacerbations | Decreased air movement during forced expiration |

| Triggers of asthma | Increased expiratory phase |

| Frequency and timing of exacerbations | Anxiety, fatigue, or confusion |

| History of intubations, ICU hospitalizations, or ED visits | Nasal flaring, retractions, and accessory muscle use |

| Cough at night | Inability to speak in complete sentences |

| Cough with exercise | Eczema |

| Allergic rhinitis symptoms | |

| Pet and tobacco exposures | |

| Family history of asthma |

ED, Emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

TREATMENT

When Should an Asthmatic Be Hospitalized?

Most asthmatics can be treated as outpatients. Table 69-4 shows key reasons for hospitalization.

| Critically ill |

| Severe airway obstruction with respiratory distress |

| Increased PaCO2 |

| Poor response to emergency department therapies |

| Greater than 3 or 4 bronchodilator treatments |

| Oxygen saturations < 90% |

| Social considerations |

| Unreliable parents, transportation, or telephone |

| Home is far from nearest medical facility |

What Are the Side Effects of Steroids?

Short courses of oral steroids generally have minor, but often distressing, temporary side effects that include increased appetite, irritability, joint aches, and stomach ache. If steroids must be used frequently in short courses or for prolonged courses (> 14 days), more prominent side effects may occur, including Cushingoid features and hyperglycemia. Table 69-5 shows common corticosteroid side effects. Oral steroids also have a bitter taste, which complicates adherence to the treatment plans for young children.

| Minor | Major |

|---|---|

| Behavior changes | Growth suppression |

| Sleep disturbances | Osteoporosis |

| Appetite changes (usually increase) | Hypothalamic-pituitary axis suppression |

| Acne or puffy red cheeks | Cushingoid appearance |

| Gastrointestinal upset and bowel habit changes | Skin thinning or striae |

| Oropharyngeal candidiasis (inhaled steroids) | Hirsutism |

| Joint aches | Immunosuppression |

| Weight gain | Hyperglycemia |

How Do I Choose a Medication for Persistent Asthma?

Table 69-6 lists different classes of maintenance medications for persistent asthma and shows some advantages and disadvantages of each. Inhaled steroids are generally the first line treatment for persistent asthma. The newer inhaled steroids—budesonide (Pulmicort), fluticasone (Flovent), or beclomethasone HFA (Qvar)—are more effective at lower doses than older preparations. Although long-acting beta-agonists are not as effective as inhaled steroids for monotherapy, medications such as salmeterol (Serevent) act synergistically with inhaled steroids and allow a decrease in steroid dose. They are available in combination with inhaled steroids, such as fluticasone/salmeterol (Advair). Recently, a small but significant increase in asthma-related deaths or life-threatening experiences was found in African-Americans older than 12 years using salmeterol in addition to their usual asthma care (Nelson et al., 2006). Montelukast (Singulair) is the preferred leukotriene modifier because it is a once-a-day medication with almost no side effects. Other leukotriene modifiers are either more difficult to administer or have more side effects: zileuton (Zyflo) must be given four times a day and can have hepatotoxicity, and zafirlukast (Accolate) must be given twice a day and has some drug-drug interactions. Mast cell stabilizers, cromolyn (Intal) and nedocromil (Tilade), have almost no effective role in the treatment of childhood asthma. Although theophylline (Theo-Dur, Slo-bid) is effective, it is not often prescribed because of the potential side effects and narrow therapeutic window.

| Class | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Inhaled steroid | Daily-BID dosing Long half-life |

Can have growth suppression at high doses |

| Long-acting beta-agonists | BID dosing | Less effective as monotherapy |

| Small but significant increase in asthma-related deaths, especially in African-Americans | ||

| Combination therapy: inhaled steroids and long-acting beta-agonists | Improved control with lower inhaled steroid doses | Both inhaled steroid and long-acting beta-agonist disadvantages |

| Antiinflammatory + bronchodilator | ||

| Leukotriene modifiers | Oral medication | Usually only effective in mild persistent asthmatics |

| Few side effects (Singulair) | ||

| Theophylline | Oral medication | Narrow therapeutic window |

| Requires drug levels | ||

| Mast cell stabilizers | Minimal side effects | Minimal therapeutic effects |

| QID dosing |

BID, Twice per day; QID, four times per day.

BRONCHIOLITIS

EVALUATION

What History and Examination Findings Are Important?

History and examination findings for bronchiolitis are shown in Table 69-7.

| History | Physical Examination |

|---|---|

| Viral prodrome | Expiratory wheezing and/or crackles |

| Copious rhinorrhea | Tachypnea (> 60 breaths/min) |

| Poor feeding | Respiratory distress (grunting, nasal flaring, retractions, etc.) |

| Apneic episodes (> 20 sec) | Lethargy and fatigue |

| Cyanosis | Signs of dehydration |

PNEUMONIA

ETIOLOGY

What Causes Bacterial Pneumonia at Different Ages?

The bacterial and bacteria-like pathogens that cause pneumonia vary at different ages, as shown in Table 69-8. Neonatally acquired Chlamydia trachomatis is often associated with a history of conjunctivitis. If pulmonary abscesses are present, Staphylococcus aureus is the most likely organism. Anaerobic organisms need to be considered in aspiration pneumonias. Recurrent pneumonias are often associated with underlying chronic diseases such as cystic fibrosis, ciliary dyskinesia syndrome, or immunodeficiencies. These diseases can lead to less common bacterial infections, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis and Pneumocystis carinii in immunocompromised patients.

Table 69-8 Common Causes of Bacterial Pneumonia at Different Ages

| Age | Pathogen |

|---|---|

| Newborn | Group B streptococci, Listeria monocytogenes, gram-negative rods |

| 1-3 months | Chlamydia trachomatis, Bordetella pertussis |

| Childhood and adolescence | Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, group A streptococci |

EVALUATION

What History and Examination Findings Are Important?

Important history and examination considerations are listed in Table 69-9. Some physical findings may be less prominent in infants. For example, decreased breath sounds or dullness to percussion may not be apparent. Tachypnea is almost always present.

| Common Findings | Findings More Common with Bacterial Pneumonia |

|---|---|

| Cough | Toxic appearance |

| Crackles | Focal areas of decreased breath sounds |

| Dyspnea | Dullness to percussion |

| Tachypnea | Pleuritic chest pain |

| Fever | Underlying chronic disease |

| Lethargy | Persistent high fevers unresponsive to antipyretics |

CROUP

ETIOLOGY

EVALUATION

What History and Examination Findings Are Important?

Important elements in the history of stridor are listed in Table 38-2 The most important physical signs to consider are the amount of respiratory distress and the degree of inspiratory stridor. Signs of “toxicity” must also be looked for. Epiglottitis is rare because of immunization against Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib); however, this disease should still be carefully considered in toxic patients with severe croup. Patients with epiglottitis are usually 2 to 7 years of age (older than typical patients with croup), have a more acute and toxic presentation, and often present with the 4 D’s: dysphagia, dysphonia, drooling, and distress. Bacterial tracheitis occurs more commonly today than epiglottitis and can also be life-threatening if not recognized. Patients have more toxic symptoms than patients with viral croup and have stridor that is less responsive to treatment. A subset of younger patients with bacterial tracheitis may appear less severely ill initially but may still need aggressive management of the tracheal membranes (Salamone et al., 2004). Foreign-body aspiration and retropharyngeal abscess should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of croup.

TREATMENT

What Medications Reduce Croup Symptoms?

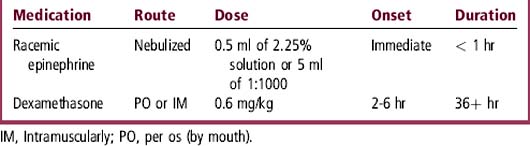

Nebulized racemic epinephrine and oral or intramuscular dexamethasone are the two medications used most often to treat croup (Table 69-11). A patient who requires nebulized racemic epinephrine in the ED should also receive dexamethasone. High-dose nebulized budesonide has shown some benefit in croup but is less effective and more expensive than intramuscular or oral dexamethasone. There is evidence that dexamethasone can effectively control croup at even the low dose of 0.15 mg/kg (Geelhoed et al., 1996). Intramuscular dexamethasone should be administered to patients with severe respiratory distress and those unable to tolerate oral dosing.

LARYNGOMALACIA

ETIOLOGY

What Is Laryngomalacia?

Laryngomalacia is a congenital disorder that causes upper airway obstruction because of collapse of the supraglottic laryngeal structures. Stridor (Chapter 38) is produced when “floppy” structures such as the aryepiglottic folds or the epiglottis are drawn into and obstruct the airway during inspiration. Laryngomalacia is associated with other airway abnormalities in some patients, but most of these are not significant. Gastroesophageal reflux is hypothesized to aggravate laryngomalacia by causing inflammation and edema of the supralaryngeal structures, leading to increased edema and obstruction.

EVALUATION

What History and Examination Findings Are Important?

Common history and physical findings in laryngomalacia are shown in Table 69-12. Laryngomalacia will classically have its onset at 2 weeks to 2 months of age, have an increase in symptoms until around age 6 to 10 months, and then resolve spontaneously by 2 years of age.

| History | Physical Examination |

|---|---|

| Stridor begins shortly after birth | Stridor |

| Worse when breathing harder (URI, crying) | Retractions |

| Worse in supine position with neck flexed | Thoracic deformities |

| Better in prone position with neck extended | Poor growth |

| Poor feeding |

URI, Upper respiratory infection.

HYPOXIA

ETIOLOGY

What Are the Common Causes of Hypoxia?

The most common cause of hypoxia is ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatch. Cardiac diseases cause hypoxia only when there is shunting of unoxygenated blood from the right to left side of the heart. Table 69-13 shows the four main causes of hypoxia. A fifth and less common cause would be decreased PaO2, which is seen mainly at high altitude.

| Cause of Hypoxia | Common Mechanisms | Changes in O2 Saturations with Supplemental O2 |

|---|---|---|

| V/Q mismatch | Asthma, pneumonia, atelectasis | Increased |

| Hypoventilation | Obstructive sleep apnea, muscular weakness, neurologic impairment | Increased |

| Shunting | Cardiac abnormalities (e.g., ASD, VSD) Intrapulmonary arteriovenous malformation |

No change |

| Diffusion impairment | Interstitial lung disease | Increased |

ASD, Atrial septal defect; V/Q, ventilation-perfusion ratio; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

TREATMENT

How Is Hypoxia Treated?

In general, oxygen is administered while the underlying disorder is identified. See Chapter 59 for a discussion of the emergency management of a child with respiratory distress and hypoxia.

When Can Oxygen Be Harmful to a Hypoxic Patient?

♦ Effective treatment of asthma must include antiinflammatory drugs (corticosteroids) if symptoms persist despite bronchodilator therapy.

♦ Respiratory rate greater than 60 breaths/min in infants with bronchiolitis is correlated with hypoxia.

♦ Community-acquired pneumonia is most often caused by a virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, or Streptococcus pneumoniae.

♦ Never send a child with suspected epiglottitis for a lateral neck x-ray.

Case 69-1 A 2-year-old child presents to clinic with a 5-week history of cough. He originally caught a cold in January from his 5-year-old brother. Nasal congestion resolved, but the cough has persisted and is present all the time. He coughs during the night, waking occasionally, and he sometimes coughs so hard that he “throws up.” He had two other bad coughing episodes associated with colds last winter and again in the fall; both cleared up slowly. He has not had fever. His weight is following the curve at the 10th percentile. Otherwise he has been healthy, has age-appropriate development, and is fully immunized. On physical examination the lung fields are clear

Case 69-2 An 8-month-old child is seen in the clinic in mid-January with first-time wheezing, cough, low-grade fever, and rhinorrhea. An albuterol treatment in the clinic did not change the symptoms

Case 69-3 A 3-year-old child is seen in the clinic for fever and cough that have worsened over the past 24 hours. He had an abrupt onset of fever 2 days ago, and the cough developed yesterday. His mother says that he looks more ill than she has ever seen him. On examination his temperature is 39.2° C, respiratory rate is 30 breaths/min, and he has intercostal retractions. Crackles are heard in the right lung

Case 69-4 A previously healthy 24-month-old child is seen in the emergency department in the early morning hours for marked shortness of breath, stridor, rhinorrhea, low-grade fever, and a brassy/harsh cough

Case 69-5 A 4-month-old infant has had a hoarse cry and noisy breathing since shortly after birth. In addition, she “snores” when she sleeps. Her parents are concerned that she might have allergies or enlarged tonsils and request a referral to an otolaryngologist

Case 69-6 A 7-year-old boy with severe asthma is seen in the emergency department (ED) in moderate distress with diffuse wheezing. He has been ill for the past week and has used his inhaler four to six times each day. Today he had difficulty climbing the stairs at school. When he arrived in the ED, his respiratory rate was 28 breaths/min and his oxygen saturation was 90% on room air. His chest radiograph demonstrates scattered atelectasis. After his third treatment with nebulized albuterol, his oxygen requirement increases from 1 to 3 L, even though his wheezing seems to have decreased

Case Answers

69-1 A Learning objective:

69-2 A Learning objective:

69-3 A Learning objective:

69-4 A Learning objective:

69-5 A Learning objective:

69-5 B Learning objective:

The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm.

Nelson H, et al. The Salmeterol Multicenter Asthma Research Trial. A comparison of usual pharmacotherapy for Asthma of Usual Pharmacotherapy Plus Salmeterol. Chest. 2006;129:15.

American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Practice Guideline. Diagnosis and management of bronchiditis. Pediatrics. 118(1774), 2006.

Geelhoed GC, Turner J, Macdonald WB. Efficacy of a small single dose of oral dexamethasone for outpatient croup: a double blind placebo controlled clinical trial. BMJ. 1996;313:140.

Salamone FN, et al. Bacterial tracheitis reexamined: is there a less severe manifestation? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:871.