10 Respiration

Examination

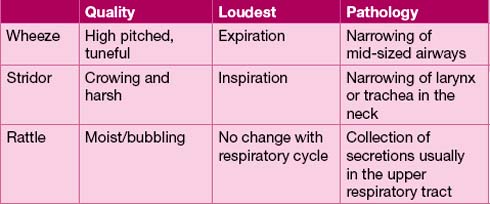

Use the scheme ‘inspection, percussion, palpation and auscultation’. Start your examination by observing the child at rest. Is there tachypnoea (see Table 10.1), recession or other evidence of respiratory distress, e.g. head bobbing in a baby or nostril flaring in a toddler? Does the child look anxious? Is there an audible noise during respiration (see Table 10.2)? Do not forget that tachypnoea may be due to fever or acidosis when there is no respiratory tract pathology.

| Age | Breaths per minute |

|---|---|

| Neonate | 40–60 |

| Infant | 30–40 |

| 5 years | 20–25 |

| 10 years | 15–20 |

In older children you should complete a formal examination of the respiratory system including checking for clubbing (see Table 10.3) and cyanosis, percussion and auscultation. Look for chest deformity – Harrison’s sulci or pectus carinatum (‘pigeon chest’). These indicate chronically increased airway resistance – most commonly due to asthma.

| System | Cause |

|---|---|

| Cardiac | Cyanotic congenital heart disease Bacterial endocarditis |

| Respiratory | Bronchiectasis Cystic fibrosis/ciliary dyskinesia Tuberculosis Empyema/abscess, malignancy |

| Gastrointestinal | Inflammatory bowel disease, chronic active hepatitis Primary sclerosing cholangitis |

| Other | Familial |

In young children, particularly under 2 years, respiratory examination needs to be opportunistic and percussion is rarely of value. Audible crackles in the chest do not always mean lung consolidation or infection, particularly in the young child. They are often heard in wheezy children where they may be due to oedema and mucus in the small airways (see Table 10.4). Think about whether there are other signs of consolidation, such as reduced air entry or bronchial breathing. Examination of the ears and throat is a challenge in a fractious toddler – it is best left until last.

Table 10.4 Severity of respiratory distress

| Grade | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Mild | Tachypnoea Mild recession No effect on feeding or speech |

| Moderate | Tachypnoea Moderate or severe recession, struggles to feed, cannot speak in full sentences Oxygen may be needed to maintain saturation |

| Severe | Tachycardia, gasping, speechless, frightened May be pale and quiet or agitated and hypoxic despite oxygen Chest may be silent and respiratory effort flagging Impaired consciousness |

Investigations

Other blood tests

Blood tests are generally over-used. A blood count and C-reactive protein measurements in children with fever and cough are unhelpful at distinguishing common viral infections from more significant bacterial lower respiratory tract infections. A high lymphocyte count will help corroborate a diagnosis of whooping cough. Urea and electrolyte measurement is really only needed if there is coexistent severe vomiting or dehydration, or in children requiring intravenous fluids. Blood cultures are necessary if a child with pneumonia is very toxic and there are concerns about associated septicaemia. IgE and blood allergy tests may help confirm atopy in the child with probable asthma. Only occasionally does it directly influence management, e.g. the wheezy baby with eczema and milk allergy. Rarely, immune function testing may be required in children with true recurrent bacterial lower respiratory tract infections (see Chapter 16, p. 241).

Upper respiratory tract infections

Upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) may be summarized as snuffles, fever and misery.

Tonsillitis

Bacterial tonsillitis is hard to distinguish on clinical grounds from viral URTI as both conditions may produce a red throat with enlargement of local glands. It is often assumed that a white exudate over enlarged and inflamed tonsils is suggestive of bacterial infection but controlled studies have not shown this. Most tonsillitis in young children is viral and even if streptococcal infection is confirmed there is little evidence that antibiotics do anything other than reduce the risk of post-infective complications such as rheumatic fever or nephritis. Antibiotics are only necessary if the infection is slow to settle and there are concerns about secondary problems such as quinsy or nephritis. Avoid ampicillin or amoxicillin, as glandular fever may be the cause – look for generalized lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly (see Chapter 16, p. 237).

Upper airways obstruction

Stridor and croup are important paediatric problems. The upper airway of children, being smaller than in adults, is more likely to obstruct with oedema of local tissues. Infections or allergies, which might produce hoarseness or loss of voice in an adult, may therefore produce alarming respiratory obstruction in a child. Acute severe stridor is an acute medical emergency. Management is described in Appendix I, p. 296.

Differential diagnosis of stridor

Croup, as is the diagnosis in Case 10.1, is the commonest cause of acute stridor. It occurs mainly in preschool children.

There is usually a viral prodrome, commonly with a barking cough. Parainfluenza virus is the commonest causative organism, and steroids are the mainstay of management. Meta-analysis of many trials has confirmed their efficacy and any child with croup severe enough to need hospital admission should receive steroids. Nebulized budesonide works more quickly than oral or parenteral steroids. In severe stridor, nebulized 1:1000 adrenaline (epinephrine), repeated as necessary, is useful as an emergency measure (see also Appendix I, p. 296).

See Table 10.5 for the differences between croup and epiglottitis.

Table 10.5 The important differences between croup and epiglottitis

| Croup | Epiglottitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Organism | Parainfluenza virus | Haemophilus influenzae b |

| Age | 6 months to 3 years | 3–7 years |

| Prodrome URTI | Usual | Uncommmon |

| Onset | Days | Hours |

| Cough | Present | Often absent |

| Dysphagia | Absent | Severe with dribbling |

| Systemic | Mildly unwell | Toxic and ill |

| Posture | No preference | Sitting/leaning forward |

Anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis can present with severe upper airways oedema leading to obstruction. Wheezing and collapse with hypotension may also occur. Severe cases may require intubation. Adrenaline (epinephrine), given either intramuscularly or intravenously, may be life-saving (see also Appendix I, p. 286). Steroids may be required for the wheeze but anti- histamines really only offer symptomatic relief for itching. Recent studies in young children have shown that milk and egg are the commonest causes, as opposed to nuts in older children and adults. Following an episode of anaphylaxis, thought should be given to allergy tests to help delineate the cause. Adrenaline (epinephrine) pens are also dispensed in increasing quantities for use in the community. Although seemingly a sensible precaution, they require thorough training, with a care plan in place for use in the school or nursery, and evidence suggests that they are rarely used.

Chronic upper airways obstruction

Rarer causes include vascular rings compressing the trachea from outside, mediastinal masses such as neuroblastoma (see Chapter 7, p. 74) and intrinsic airway conditions such as haemangiomas and webs. Babies with anything other than very mild stridor should have a plain chest X-ray and a barium swallow. A barium swallow is more effective than echocardiography in picking up vascular rings. Moderate to severe stridor requires direct laryngoscopy to look for intrinsic lesions such as airway haemangiomas. The prognosis for laryngomalacia is excellent, with the noisy breathing diminishing with age as the cartilage strengthens.

Chronic cough

The assessment should inquire about the nature of the cough, any sputum production, and any associated symptoms or relevant past medical history. A paroxysmal cough suggests pertussis; night-time, or exercise-induced cough might suggest asthma; sputum production and fever suggest bronchiectasis or tuberculosis. Relationship to posture or feeds may occur with gastro-oesophageal reflux. A history of choking may indicate an inhaled foreign body. Immune deficiency or cystic fibrosis will usually cause failure to thrive. Tracheo-oesophageal fistula (see Chapter 17, p. 259), is associated with a characteristic ‘TOF cough’.

Pertussis

Pertussis, or whooping cough, is caused by Bordatella pertussis. It invades the pulmonary ciliary epithelium causing bronchial congestion and inflammation, with peribronchial lymphoid hyperplasia (catarrhal stage 1–2 weeks). Wide-spread epithelial necrosis then ensues, with the characteristic coughing bouts (paroxysmal stage 2–4 weeks), and predisposes to atelectasis and bronchopneumonia. Paroxysms of coughing with a terminal ‘whoop’ are characteristic (as in Case 10.2). Children are unable to catch their breath and may become cyanosed. Apnoea occurs in young infants. Vomiting is common. Pneumonia accounts for 80–90% of deaths from pertussis. Seizures (3%) and encephalopathy (1%) may occur. The convalescent phase lasts from 1–2 weeks to many months. Use of antibiotics in the catarrhal stage may shorten the illness but, if started in the convalescent stage, has no effect on the duration of illness, although infectivity to others is alleviated. In adults and older children, who are the usual sources of infection, the cough is a dry, repetitive, ‘staccato’ cough.

Large-scale outbreaks of whooping cough in Britain and the USA in 2011-12, to levels not seen for over 50 years, have led to concerns that the current whooping cough immunization schedule (see Chapter 1, p. 3) does not provide long-lasting immunity. The introduction of a further booster immunization for secondary school children and pregnant women is under consideration. Booster immunizations for healthcare workers have now been recommended.

The wheezy child

Acute wheezing

Bronchodilators through a large volume spacer have largely replaced nebulized treatment as the preferred option for initial treatment of acute wheezing in childhood. Careful assessment is needed and measures including oxygen and systemic steroids are needed in moderate to severe wheezing. See Figures I.14 and I.15 in Appendix I for full assessment and management.

Bronchiolitis

Bronchiolitis is a term used to describe an acute respiratory infection, in children under 1 year, where wheezing may be present (as in Case 10.3). The cardinal signs are crepitations and expiratory wheeze with recession and, if severe, cyanosis. The baby initially has snuffles, which progress to a characteristic dry, hacking cough. RSV is the commonest cause of bronchiolitis, but is not a prerequisite for diagnosis. Treatment is supportive therapy with oxygen, nasogastric feeding and occasionally CPAP or even ventilation in those most severely affected (1–2%). Bronchodilators may help those with prominent wheeze, but controlled trials have failed to show clinical benefit of these or other treatments such as steroids, antibiotics, adrenaline (epinephrine) or specific antiviral treatment. Prophylactic treatment with the monoclonal antibody palivizumab is advocated for some high-risk infants, particularly those on home oxygen, to prevent life-threatening bronchiolitis.

Persistent wheezing

Chronic wheeze

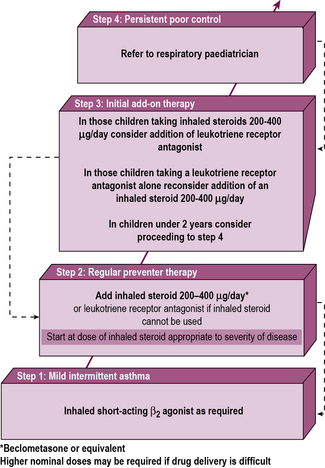

This is classical asthma with frequent, often daily, symptoms, affecting sleep and exercise (as in Case 10.4). Background atopy is common. Management is as outlined in current British guidelines for asthma management, with inhaled steroids being the mainstay. If there is doubt over a diagnosis of asthma, particularly in children too young to provide peak flows, a trial of inhaled steroids is a sensible way forward. Review the situation after 6 to 8 weeks – do not continue inhaled steroids if they are not helping.

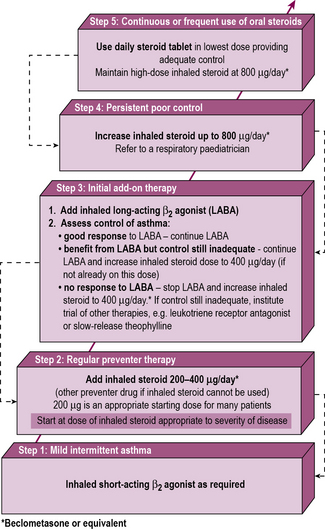

See Figures 10.2 and 10.3 for a summary of stepwise management in children.

Figure 10.2 Summary of stepwise management in children aged less than 5 years.

(Reproduced from British Guideline for the Management of Asthma.)

Figure 10.3 Summary of stepwise management in children aged 5–12 years.

(Reproduced from British Guideline on the Management of Asthma.)

Lower respiratory tract infections

Classical lobar pneumonia is due to extensive alveolar consolidation, and airways obstruction is not seen. The child presents unwell with a fever and there may be no symptoms to point to the respiratory tract (as in Case 10.5).

Uncommon serious infections

HIV infection

HIV infection is usually acquired perinatally in childhood. It should be seen less often following the introduction of universal HIV screening in pregnancy in the UK. It may remain asymptomatic for many years in childhood, but if untreated it may present in the first few months with severe respiratory disease. The protozoan Pneumocystis carinii is the commonest cause of severe pneumonia. High-dose intravenous co-trimoxazole is the treatment of choice, but mortality remains high. Avoidance of breast-feeding, delivery by caesarean section and prophylactic zidovudine have been shown to reduce perinatal acquisition of HIV dramatically. In those infected in childhood, combination anti-retroviral therapy has improved prognosis (see Chapter 16, p. 242).

Cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the commonest genetic condition seen in Caucasian populations. It is inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion with the CF mutation present on the long arm of chromosome 7. Over a thousand mutations are known, with AF508 being the commonest, accounting for 80% of mutations in the UK. Affected individuals may have compound heterozygosity for two different mutations. The cellular transport mechanism that is affected is primarily a chloride channel – cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR). CFTR maintains an ionic gradient over the surface of the cells lining the epithelium, which keeps the cell surface moist. When CFTR malfunctions, respiratory and other epithelial surfaces dry out, resulting in tenacious, viscid secretions (see Box 10.1).

Box 10.1

Clinical presentations of cystic fibrosis

Respiratory management

Nutritional management

Maintaining adequate nutrition and growth is the key principle of management. Pancreatic enzymes before meals are given to the vast majority of patients who have pancreatic insufficiency (>85%). High-fat, high-calorie diets are the preferred option, to maintain nutrition and dietary supplements, and enteral feeding via gastrostomy is used if growth is failing. Fat-soluble vitamin replacement is also necessary. Complications should be treated vigorously (see Box 10.2). CF-related diabetes (CFRD) develops in a significant proportion of adolescents with CF. Annual screening with a glucose tolerance test is recomended from age 12 years, as patients are often asymptomatic. Untreated CFRD is associated with poorer lung function, more frequent chest infections and impaired nutritional status. Treatment is with insulin via multiple daily injections or an insulin pump.

Box 10.2

Long-term complications of cystic fibrosis