2 Resourcing Critical Care

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

• describe historical influences on the development of critical care and the way this resource is currently viewed and used

• explain the organisational arrangements and interfaces that may be established to govern a critical care unit

• identify external resources and supports that assist in the governance and management of a critical care unit

• describe considerations in planning for the physical design and equipment requirements of a critical care unit

• describe the human resource requirements, supports and training necessary to ensure a safe and appropriate workforce

• explain common risks and the appropriate strategies, policies and contingencies necessary to support staff and patient safety

• discuss leadership and management principles that influence the quality, efficacy and appropriateness of the critical care unit

• discuss common considerations from a critical care perspective in responding to the threat of a pandemic.

Introduction

In 1966 Dr B Galbally, a hospital resuscitation officer at St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne, published the first article on the planning and organisation of an intensive care unit (ICU) in Australia.1 He identified that critically ill patients who have a reasonable chance of recovery require life-saving treatments and constant nursing and medical care, but this intensity of service delivery ‘does not necessarily continue until the patient dies, and it should not continue after the patient is considered no longer recoverable’.1

The need for prudent and rational allocation of limited financial and human resources was as important for Australia’s first ICU (St Vincent’s, Melbourne, 1961) as it is for the 200 or more now scattered across Australia and New Zealand. This chapter explores the influences on the development of critical care and the way this resource is currently viewed and used; describes various organisational, staffing and training arrangements that need to be in place; considers the planning, design and equipment needs of a critical care unit; covers other aspects of resource management including the budget; and finishes with a description of how critical care staff may respond to a pandemic. First, however, important ethical decisions in managing the resources of a critical care unit, which are just as important as the ethical resources that govern the care decisions for an individual patient (see Chapter 6), are discussed below.

Ethical Allocation and Utilisation of Resources

At the other extreme is the utilitarian view, which suggests an action is right only if it achieves the greatest good for the greatest number of people. This concept tends to sit well with pragmatic managers and policy makers.2 An example of a utilitarian view might be to ration funding allocated to heart transplantation and to utilise any saved money for prevention and awareness campaigns. A heart disease prevention campaign lends a greater benefit to a greater number in the population than does one transplant procedure.

Historical Influences

An often-held view is that managers in government health services have no incentive to spend or expand services.3 However, the opposite is probably true. Developing larger and more sophisticated services such as ICUs can attract media and public attention. The 1960s and early 1970s saw the development of the first critical care units in Australia and New Zealand. If a hospital was to be relevant, it had to have one. In fact, what distinguished a tertiary referral teaching hospital from other hospitals was, at its fundamental conclusion, the existence of a critical care unit.4 Over time, practical reasons for establishing critical care units have led to their spread to most acute hospitals with more than 100 beds. Reasons for the proliferation of critical care services include, but are not limited to:

• economies of scale by cohorting critically ill patients to one area

• development of expertise in doctors and nurses who specialise in the care and treatment of critically ill patients

• an ever-growing body of research demonstrating that critically ill patient outcomes are better if patients are cared for in a specifically equipped and staffed critical care unit.4

Funding for critical care services has evolved over time to be somewhat separate from mainstream patient funding, owing to the unique requirements of critical care units. Critical care is unique because patients are at the severe end of the disease spectrum. For instance, the funding provided for a patient admitted for chronic obstructive airway disease in an ICU on a ventilator is very different from that provided for a patient with the same diagnosis, but treated only in a medical ward. Each jurisdictional health department tends to create its own unique approach to funding ICU services in its jurisdiction.5 For instance, Queensland tends to fund ICU patients who are specifically identified and defined in the Clinical Services Capability Framework for Intensive Care6 with a prescribed price per diem, depending on the level of intensive care given to the patient or a price per weighted activity unit, as defined in the business rules and updated on an annual basis.7 In Victoria, the diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment for individual patient types admitted to the hospital also pays for ICU episodes, with some co-payment elements added for mechanical ventilation.8 In New South Wales a per diem rate is established for ICU patients, while high-dependency patients in ICU are funded through the hospital DRG payment; in South Australia a flat per diem rate exists.9,10 Most other states have a global ICU budget payment system based on funded beds or expected occupied bed days in the ICU. However, within states and specific health services and hospitals the actual allocation of funding to the ICU may vary, depending on the nature of the specific ICU and demands and priorities of the health service.11

The RAND study12 examined funding methods in many countries and concluded that there was no obvious example of ‘best practice’ or a dominant approach used by a majority of systems. Each approach had advantages and disadvantages, particularly in relation to the financial risk involved in providing intensive care. While the risk of underfunding intensive care may be highest in systems that apply DRGs to the entire episode of hospital care, including intensive care, concerns about potential underfunding were voiced in all systems reviewed. Arrangements for additional funding in the form of co-payments or surcharges may reduce the risk of underfunding. However, these approaches also face the difficulty of determining the appropriate level.12

At the hospital level, most critical care units have capped and finite budgets that are linked to ‘open beds’ – that is, beds that are equipped, staffed and ready to be occupied by a patient, regardless of whether they are actually occupied.13 This is one crude yet common way that hospitals can control costs emanating from the critical care unit. The other method is to limit the number of trained and experienced nurses available to the specialty; consequently, a shortage of qualified critical care nurses results in a shortage of critical care beds, resulting in a rationing of the service available. The capping of beds and qualified critical care nurse positions can be convenient mechanisms to limit access and utilisation of this expensive service – critical care.

Economic Considerations and Principles

One early comprehensive study of costs found that 8% of patients admitted to the ICU consumed 50% of resources but had a mortality rate of 70%, while 41% of patients received no acute interventions and consumed only 10% of resources.14 More recent Australian studies show that, although critical care service is increasingly being provided to patients with a higher severity of acute and chronic illnesses, long-term survival outcome has improved with time, suggesting that critical care service may still be cost-effective despite the changes in case-mix.15,16

An Australian study showed that in 2002, ICU patients cost around $2670 per day or $9852 per ICU admission, with more than two-thirds going to staff costs, one-fifth to clinical consumables and the rest to clinical support and capital expenditure.17 Nevertheless, some authors provide scenarios as examples of poor economic decision making in critical care and argue for less extreme variances in the types of patient ICUs choose to treat in order to reduce the burden of the health dollar.18,19 Others have suggested that if all healthcare provided were appropriate, rationing would not be required.3 Defining what is ‘appropriate’ can be subjective, although not always. The RAND12,20 group suggests that there are at least three approaches that can be used to assess appropriateness of care (Table 2.1). These include the benefit–risk, benefit–cost and implicit approaches.

| Approach | Description |

|---|---|

| Benefit–risk approach | The benefit of treatment and the inherent risks to the patient are assessed to inform a decision; this approach excludes monetary costs. |

| Benefit–cost approach | Evaluate the benefit and cost of the decision to proceed; this approach incorporates cost to patient and society. |

| Implicit approach | The medical practitioner provides the service and judges its appropriateness. |

The quality of the outcome is a function of the benefit to be achieved and the sustainability of the benefit. The benefit of critical care is associated with such factors as survival, longevity and improved quality of life (e.g. greater functioning capacity and less pain and anxiety). The benefit is enhanced by sustainability: the longer the benefit is maintained, the better it is.21

Cost is separated into two components, monetary (price) and non-monetary (suffering). Non-monetary costs include such considerations as morbidity, mortality, pain and anxiety in the individual, or broader societal costs and suffering (e.g. opportunity costs to others who might have used the resources but for the current occupants, and what other health services might have been provided but for the cost of this service).21

Ethico-economic analyses of services like critical care and expensive treatments like organ transplantation are the new consideration of this century and are as important to good governance as are discussions of medico-legal considerations. Sound ethical principles to inform and guide human and material resource management and budgets ought to prevail in the management of critical care resources.2

Budget

This section provides information on types of budget, the budgeting process, and how to analyse costs and expenditure to ensure that resources are utilised appropriately. As noted by one author, ‘Nothing is so terrifying for clinicians accustomed to daily issues of life and death as to be given responsibility for the financial affairs of their hospital division!’.3 Yet, in essence, developing and managing a budget for a critical care unit follows many of the same principles as managing a family budget. Consideration of value for money, prioritising needs and wants, and living within a relatively fixed income is common to all. This section in no way undermines the skill and precision provided by the accounting profession, nor will it enable clinicians to usurp the role of hospital business managers. Rather, the aim is to provide the requisite knowledge to empower clinicians to manage the key components of budget development and budget setting, and to know what questions to ask when confronted by this most daunting responsibility of managing a unit’s or service’s budget.

Types of Budget

Personnel Budget

Personnel budgets tend to be fixed costs, in that the majority of staff are employed permanently, based on an expected or forecast demand. Prudent managers tend to employ 5–10% less than the actual forecast demand and use casual staff to ‘flex-up’ the available FTE staff establishment in periods of increasing demand, hence contributing a small but variable component to the personnel budget.22

Budget Process

Budget Analysis and Reporting

Most critical care managers analyse their expenditure against budget projections on a monthly basis, to identify variances from planned expenditure. Information should not merely be financial: a breakdown of the monthly and year-to-date expenditures for personnel (productive and non-productive), and operational (fixed and variable) costs, should be matched against other known measurable indicators of activity or productivity (e.g. patient bed-days, patient types/DRGs and staffing hours, including overtime and other special payments).3

Budget Control and Action

When signs of poor performance or financial overrun are evident, managers cannot merely analyse the financial reports, hoping that things will sort themselves out. Every variance of a sizeable amount requires an explanation. Some will be obvious: an outbreak of community influenza among staff will increase sick leave and casual staff costs for a period of time. Other overruns can be insidious but no less important: overtime payments, although sometimes unavoidable, can also reflect poor time management or a culture of some staff wanting to boost their income surreptitiously.22

Developing A Business Case

The most common reason for writing a business case is to justify the resources and capital expenditure to gain the support and/or approval for a change in service provision and/or purchase of a significant new piece of equipment/technology. This section provides an overview of a business case and a format for its presentation. The business case can be an invaluable tool in the strategic decision-making process, particularly in an environment of constrained resources.23

A business case is a management tool that is used in the process of meeting the overall strategic plan of an organisation. Within a setting such as healthcare, the business case is required to outline clearly the clinical need and implications to be understood by leaders. Financial imperatives, such as return on investment, must also be defined and identified.23–25 A business case is a document in which all the facts relevant to the case are documented and linked cohesively. Various templates are available (see Online Resources) to assist with the layout. key questions are generally the starting point for the response to a business case: why, what, when, where and how, with each question’s response adding additional information to the process (Table 2.2). Business cases can vary in length from many pages to just a couple. Most organisations will have standardised headings and formats for the presentation of these documents. If the document is lengthy, the inclusion of an executive summary is recommended, to summarise the salient points of the business case (Box 2.1).

| Question | Example |

|---|---|

| Why? | What is the background to the project, and why is it needed: PEST (political, economic, sociological, technological) and SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) analysis? |

| What? | Clearly identify and define the project and the purpose of the business case and outline the solution. Clearly defined, measurable benefits should be documented; goals and outcomes. |

| What if? | A risk assessment of the current situation, including any controls currently in place to address/mitigate the issue, and a risk assessment following the implementation of the proposed solution. |

| When? | What are the timelines for the implementation and achievement of the project/solution? |

| Where? | What is the context within which the project will be undertaken, if not already included in the background material? |

| How? | How much money, people and equipment, for example, will be required to achieve the benefits? A clear cost–benefit analysis should be included in response to this question. |

Critical Care Environment

A critical care unit is a distinct unit within a hospital that has easy access to the emergency department, operating theatre and medical imaging. It provides care to patients with a life-threatening illness or injury and concentrates the clinical expertise and technological and therapeutic resources required.26 The College of Intensive Care Medicine (CICM) defines three levels of intensive care to support the role delineation of a particular hospital, dependent upon staffing expertise, facilities and support services.27 Critical care facilities vary in nature and extent between hospitals and are dependent on the operational policies of each individual facility. In smaller facilities, the broad spectrum of critical care may be provided in combined units (intensive care, high-dependency, coronary care) to improve flexibility and aid the efficient use of available resources.26

Organisational Design

The functional organisational and unit designs are governed by available finances, an operational brief and the building and design standards of the state or country in which the hospital is located. A critical care unit should have access to minimum support facilities, which include staff station, clean utility, dirty utility, store room(s), education and teaching space, staff amenities, patients’ ensuites, patients’ bathroom, linen storage, disposal room, sub-pathology area and offices. Most notably, the actual bed space/care area for patients needs to be well designed.26

The design of the patient’s bed-space has received considerable attention in the past few years. In Australia, most state governments have developed minimum guidelines to assist in the design process. Each bed space should be a minimum of 20 square metres and provide for visual privacy from casual observation. At least one handbasin per single room or per two beds should be provided to meet minimum infection control guidelines.26 Each bed space should have piped medical gases (oxygen and air), suction, adequate electrical outlets (essential and non-essential), data points and task lighting sufficient for use during the performance of bedside procedures. Further detailed descriptions are available in various health department documents.26

Equipment

Initial Set-Up Requirements

Critical care units require baseline equipment that allows the unit to deliver safe and effective patient care. The list of specific equipment required by each individual unit will be governed by the scope of that unit’s function. For example, a unit that provides care to patients after neurosurgery will require the ability to monitor intracranial pressure. Table 2.3 lists the basic equipment requirements for a critical care unit.

| Monitoring | Therapeutic |

|---|---|

CT = computerised tomography; CVVHDF = continuous veno-venous haemodiafiltration; EDD-f = extended daily dialysis filtration; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; PiCCO = pulse-induced contour cardiac output.

Purchasing

The procurement of any equipment or medical device requires a rigorous process of selection and evaluation. This process should be designed to select functional, reliable products that are safe, cost-effective and environmentally conscious and that promote quality of care while avoiding duplication or rapid obsolescence.28 In most healthcare facilities, a product evaluation committee exists to support this process, but if this is not the case it is strongly recommended that a multidisciplinary committee be set up, particularly when considering the purchase of equipment requiring capital expenditure.29

The product evaluation committee should include members who have an interest in the equipment being considered and should comprise, for example, biomedical engineers and representatives from the central sterile supply unit (CSSU), administration, infection control, end users and other departments that may have similar needs. Once a product evaluation committee has been established, clear, objective criteria for the evaluation of the product should be determined (Box 2.2). Ideally, the committee will screen products and medical devices before a clinical evaluation is conducted to establish its viability, thus avoiding any unnecessary expenditure in time and money.28

Staff

Staffing Roles

There are a number of different nursing roles in the ICU nursing team, and various guidelines determine the requirements of these roles. Both the Australian College of Critical Care Nurses (ACCCN) (see Appendix B2) and the World Federation of Critical Care Nurses (WFCCN) (see Appendix A2) have position statements surrounding the critical care workforce and staffing. A designated nursing manager (nursing unit manager/clinical nurse consultant/nurse practice coordinator/clinical nurse manager, or equivalent title) is required for each unit to direct and guide clinical practice. The nurse manager must possess a post-registration qualification in critical care or in the clinical specialty of the unit.27,30 A clinical nurse educator (CNE) should be available in each unit. The ACCCN recommends a minimum ratio of one full-time equivalent (FTE) CNE for every 50 nurses on the roster, to provide unit-based education and staff development.27,30 The clinical nurse consultant (CNC) role is utilised at the unit, hospital and area health service level to provide resources, education and leadership.30 Registered nurses within the unit are generally nurses with formal critical care postgraduate qualifications and varying levels of critical care experience.

Prior to the mid-1990s, when specialist critical care nurse education moved into the tertiary education sector, critical care education took the form of hospital-based certificates.31 Since this move, postgraduate, university-based programs at the graduate certificate or postgraduate diploma level are now available, although some hospital-based courses that articulate to formal university programs continue to be accessible. The ACCCN (see Appendix B1) and the WFCCN (see Appendix A1) have developed position statements on the provision of critical care nursing education. Various support staff are also required to ensure the efficient functioning of the department, including, but not limited to, administrative/clerical staff, domestic/ward assistant staff and biomedical engineering staff.

Staffing Levels

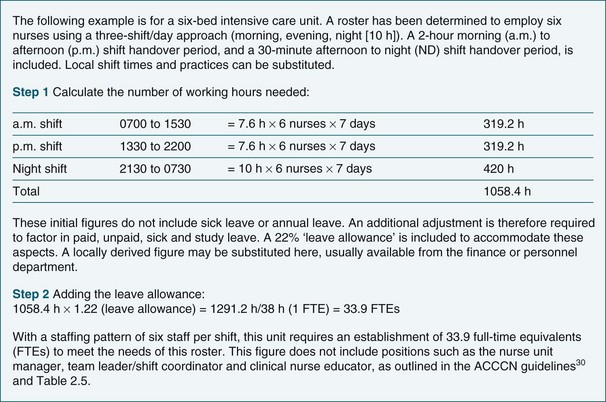

The starting point for most units in the establishment of minimum, or base, staffing levels is the patient census approach. This approach uses the number and classification (ICU or HDU) of patients within the unit to determine the number of nurses required to be rostered on duty on any given shift. In Australia and New Zealand a registered nurse-to-patient ratio of 1 : 1 for ICU patients and 1 : 2 for high-dependency unit (HDU) patients has been accepted for many years. Recently in Australia there have been several projects examining the use of endorsed enrolled nurses (EEN) in the critical care setting. The New South Wales project identified difficulties with EENs undertaking direct patient care, but determined that there may be a role for them in providing support and assistance to the RN.27,30,32 Other countries, such as the USA, have lower nurse staffing levels, but in those countries nursing staff is augmented by other types of clinical or support staff, such as respiratory technicians.33 The limitations of this staffing approach are discussed later in this chapter. Once the base staffing numbers per shift have been established, the unit manager is required to calculate the number of full-time equivalents that are required to implement the roster. In Australia, one FTE is equal to a 38-hour working week.

Nurse-To-Patient Ratios

Nurse-to-patient ratios refer to the number of nursing hours required to care for a patient with a particular set of needs. With approximately 30% of Australian and New Zealand units identified as combined units incorporating intensive care, coronary care and high-dependency patients,34 different nurse-to-patient ratios are required for these often diverse groups of patients. It is important to note that nurse-to-patient ratios are provided merely as a guide to staffing levels, and implementation should depend on patient acuity, local knowledge and expertise.

Within the intensive care environment in Australia and New Zealand, there are several documents that guide nurse-to-patient ratios (Table 2.4). The ACCCN has developed and endorsed two position statements that identify the need for a minimum nurse-to-patient ratio of 1 : 1 for intensive care patients and 1 : 2 for high-dependency patients.30,35 In New Zealand, the Critical Care Nurses Section of the New Zealand Nursing Organisation (NZNO)32 also determines that critically ill or ventilated patients require a minimum 1 : 1 nurse-to-patient ratio. Both of these nursing bodies state that this ratio is clinically determined. The WFCCN states that critically ill patients require one registered nurse to be allocated at all times.36 The College of Intensive Care Medicine (CICM) also identifies the need for a minimum nurse-to-patient ratio of 1 : 1 for intensive care patients and 1 : 2 for high-dependency patients.27,37

TABLE 2.4 Documents that guide the nurse-to-patient ratios in critical care

| Document | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| ACCCN: Position statement on intensive care nurse staffing30 |

• All intensive care patients must have a registered nurse (division 1) allocated exclusively to their care.

• High-dependency or step-down patients (in intensive care) who require a nurse-to-patient ratio of 1 : 2 should have a registered nurse (division 1) allocated exclusively to their care.

• Enrolled nurses (division 2) and unlicensed assistive personnel may be allocated roles to assist the registered nurse, but any activities that involve direct contact with the patient must always be performed in the immediate presence of the registered nurse (division 1).

• The critically ill and/or ventilated patient will require a minimum 1 : 1 nurse-to-patient ratio.

• At times, patients in the critical care unit may have higher or lower nursing acuity; the critical care nurse in charge of the shift determines any variation from the 1 : 1 ratio, taking into account context, skill mix and complexity.

• A minimum of 1 : 1 nursing is required for ventilated and other similarly critically ill patients, and nursing staff must be available to greater than 1 : 1 ratio for patients requiring complex management (e.g. ventricular assist device).

• The majority of nursing staff should have a post-registration qualification in intensive care or in the specialty of the unit.

• All nursing staff in the unit responsible for direct patient care should be registered nurses.

• The ratio of nursing staff to patients should be 1 : 2.

• All nursing staff in the HDU responsible for direct patient care should be registered nurses, and the majority of all senior nurses should have a post-registration qualification in intensive care or high-dependency nursing.

• A minimum of two registered nurses should be present in the unit at all times when a patient is present.

ACCCN = Australian College of Critical Care Nurses; NZNO = New Zealand Nurses Organisation; WFCCN = World Federation of Critical Care Nurses; CICM = College of Intensive Care Medicine.

The ACCCN30 and the NZNO Critical Care Nurses Section32 have outlined the appropriate nurse staffing standards in Australia and New Zealand for ICUs within the context of accepted minimum national standards and evidence that supports best practice. The ACCCN statement identified 10 key principles to meet the expected standards of critical care nursing (Table 2.5).

TABLE 2.5 Ten key points of intensive care nursing staffing30

| Point | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. ICU patients (clinically determined) | Require a standard nurse-to-patient ratio of at least 1 : 1. |

| 2. High dependency patients (clinically determined) | Require a standard nurse-to-patient ratio of at least 1 : 2 |

| 3. Clinical coordinator (team leader) | There must be a designated critical-care-qualified senior nurse per shift who is supernumerary and whose primary role is responsibility for the logistical management of patients, staff, service provision and resource utilisation during a shift. |

| 4. ACCESS nurses | These are nurses in addition to the bedside nurses, clinical coordinator, unit manager, educators and non-nursing support staff. They provide Assistance, Coordination, Contingency, Education, Supervision and Support. |

| 5. Nursing manager | At least one designated nursing manager (NUM/CNC/NPC/CNM or equivalent) who is formally recognised as the unit nurse leader is required per ICU. |

| 6. Clinical nurse educator | At least one designated CNE should be available in each unit. The recommended ratio is one FTE CNE for every 50 nurses on the ICU roster. |

| 7. Clinical nurse consultants | Provide global critical care resources, education and leadership to specific units, to hospital and area-wide services, and to the tertiary education sector. |

| 8. Critical care nurses | The ACCCN recommends an optimum specialty qualified critical care nurse proportion of 75%. |

| 9. Resources | These are allocated to support nursing time and costs associated with quality assurance activities, nursing and multidisciplinary research, and conference attendance. |

| 10. Support staff | ICUs are provided with adequate administrative staff, ward assistants, manual handling assistance/equipment, cleaning and other support staff to ensure that such tasks are not the responsibility of nursing personnel. |

ACCCN = Australian College of Critical Care Nurses; CNC = clinical nurse consultant; CNE = clinical nurse educator; CNM = clinical nurse manager; FTE = full-time equivalent; NPC = nurse practice coordinator; NUM = nursing unit manager.

Patient Dependency

Patient dependency refers to an approach to quantify the care needs of individual patients, so as to match these needs to the nursing staff workload and skill mix.38 For many years, patient census was the commonest method for determining the nursing workload within an ICU. That is, the number of patients dictated the number of nurses required to care for them, based on the accepted nurse-to-patient ratios of 1 : 1 for ICU patients and 1 : 2 for HDU patients. This reflects the unit-based workload, and is also the common funding approach for ICU bed-day costs.

The nursing workload at the individual patient level, however, is also reflective of patient acuity, the complexity of care required and both the physical and the psychological status of the patient.38 Strict adherence to the patient census model leads to the inflexibility of matching nursing resources to demand. For example, some ICU patients receive care that is so complex that more than one nurse is required, and an HDU patient may require less medical care than an ICU patient, but conversely may require more than 1 : 2 nursing care level secondary to such factors as physical care requirements, patient confusion, anxiety, pain or hallucinations.38 A patient census approach therefore does not allow for the varying nursing hours required for individual patients over a shift, nor does it allow for unpredicted peaks and troughs in activity, such as multiple admissions or multiple discharges.

There are many varied patient dependency/classification tools available, with their prime purpose being to classify patients into groups requiring similar nursing care and to attribute a numerical score that indicates the amount of nursing care required. Patients may also be classified according to the severity of their illness. These scoring systems are generally based on physiological variables, such as the acute physiological and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) and simplified acute physiology score (SAPS) systems. Although these scoring systems have value in determining the probability of in-hospital mortality, they are not good predictors of nursing dependency or workload.38

The therapeutic intervention scoring system (TISS) was developed to determine severity of illness, to establish nurse-to-patient ratios and to assess current bed utilisation.38 This system attributes a score to each procedure/intervention performed on a patient, with the premise that the greater the number of procedures performed, the higher the score, the higher the severity of illness, the higher the intensity of nursing care required.38 Since its development in the mid-1970s, TISS has undergone multiple revisions, but this scoring system, like APACHE and SAPS, still captures the therapeutic requirements of the patient. It does not, however, capture the entirety of the nursing role. Therefore, while these scoring systems may provide valuable information on the acuity of the patients within the ICU, it must be remembered that they are not accurate indicators of total nursing workload. Other specific nursing measures have been developed, but have not gained widespread clinical acceptance in Australia or New Zealand. (For further discussion of nursing workload measures, see Measures of Nursing Workload or Activity in this chapter.)

While not strictly workload tools, various early warning scoring systems are increasingly being used to facilitate the early detection of the deteriorating patient. These early warning systems generally take the format of a standardised observation chart with an in-built ‘track and trigger’ process.39–41

Skill Mix

Skill mix refers to the ratio of caregivers with varying levels of skill, training and experience in a clinical unit. In critical care, skill mix also refers to the proportion of registered nurses possessing a formal specialist critical care qualification. The ACCCN recommends an optimum qualified critical care nurse to unqualified critical care nurse ratio of 75%30 (see Appendix B2). In Australia and New Zealand, approximately 50% of the nurses employed in critical care units currently have some form of critical care qualification.34

Debate continues in an attempt to determine the optimum skill mix required to provide safe, effective nursing care to patients.42–48 Much of the research fuelling this debate has been undertaken in the general ward setting, and still predominantly in the USA. However, it has provided the starting point for specialty fields of nursing to begin to examine this issue. The use of nurses other than registered nurses in the critical care setting has been discussed as one potential solution to the current critical care nursing shortage. Projects in Australia trialling the use of EENs in the critical care environment have largely proved inconclusive.49

Published research on skill mix has examined the substitution of one grade of staff with a lesser skilled, trained or experienced grade of staff and has utilised adverse events as the outcome measure. A significant proportion of research suggests that a rich registered nurse skill mix reduces the occurrence of adverse events.42–48 A comprehensive review of hospital nurse staffing and patient outcomes noted that existing research findings with regard to staffing levels and patient outcomes should be used to better understand the effects of skill mix dilution, and justify the need for greater numbers of skilled professionals at the bedside.50

While there has not been a formal examination of skill mix in the critical care setting in Australia and New Zealand, two publications51,52 informing this debate emerged from the Australian Incident Monitoring Study–ICU (AIMS–ICU). Of note, 81% of the reported adverse events resulted from inappropriate numbers of nursing staff or inappropriate skill mix.51 Furthermore, nursing care without expertise could be considered a potentially harmful intrusion for the patient, as the rate of errors by experienced critical care nurses was likely to rise during periods of staffing shortages, when inexperienced nurses required supervision and assistance.51 These important findings provide some insight into the issues surrounding skill mix.

In Australia and New Zealand, an annual review of intensive care resources53 reported that there were 6633.7 FTE registered nurses currently employed in the critical care nursing workforce (5587.2 in the public sector and 1046.5 in the private sector). More recently, in 2005, categories of nurses in the workforce other than registered nurses were captured and reported for the first time, showing that there were 53.9 FTE enrolled nurses currently employed in the critical care setting in Australia (44.6 in the public sector and 9.3 in the private sector).34 Enrolled nurse training has not occurred in New Zealand since 1993, and those who are currently employed in the healthcare system are restricted to a scope of practice that does not call for complex nursing judgements. Thus, no enrolled nurses were reported to be working in critical care settings at the time of the most recent annual review of intensive care resources in New Zealand.34

Other professional organisations have also developed position statements on the use of staff other than registered nurses in the critical care environment.54,55 The Canadian Association of Critical Care Nurses (CACCN) states that non-regulated personnel may provide non-direct and direct patient care only under the supervision of registered nurses.54 The British Association of Critical Care Nurses (BACCN) similarly determines that healthcare assistants employed in a critical care setting must undertake only direct patient care activities for which they have received training and for which they have been assessed competent under the supervision of a registered nurse.55

Rostering

The traditional shift pattern is contingent on a 38-hour per week roster for full-time staff and is based on 8-hour morning and evening shifts, with the option of a 10-hour night shift (Figure 2.1). With the increased demand for flexible rosters has come the introduction of additional shift lengths, most notably the 12-hour shift. The implementation of a 12-hour roster requires careful consideration of its risks and benefits, with full consultation of all parties, unit staff, hospital management and the relevant nurses’ union. Perceived benefits of working a 12-hour roster include improvement in personal/social life, enhanced work satisfaction and improved patient care continuity. Perceived risks, such as an alteration in the level of sick-leave hours, decreased reaction times and reduced alertness during the longer shift, have not been found to be significant.56 A reported disadvantage of 12-hour shifts is the loss of the shift overlap time, which has traditionally been used for providing in-unit educational sessions. A consideration, therefore, for units proposing the implementation of a 12-hour shift pattern is to build formal staff education sessions into the proposal.

Education and Training

Some organisations, both private and public, continue to offer a variety of short continuing education courses as well, generally at a fairly basic level of knowledge and skills, but which play a role in providing an introduction for a novice practitioner.31 Position statements on the preparation and education of critical care nurses are available31,57,58 that present frameworks to ensure that the curricula of courses provide adequate content to prepare nurses for this specialist nursing role (see Appendices A1 and B2).

Orientation

The term orientation reflects a range of activities, from a comprehensive unit-based program, attendance at a hospital induction program covering the mandatory educational requirements of that facility, through to familiarisation with the layout of a department. The aim of an orientation program is the development of safe and effective practitioners.59

Unit-specific orientation should be a formal, structured program of assessment, demonstration of competence and identification of ongoing educational needs, and should be developed to meet the needs of all staff who are new to the unit. Competency-based orientation is learner-focused and based on the achievement of core competencies that reflect unit needs and enable new employees to function in their role at the completion of the orientation period.60 The ACCCN Competency Standards for Specialist Critical Care Nurses61 may be used as a framework on which to build competency-based orientation programs.

Continuing Education

In 2003, both the Royal College of Nursing Australia and the College of Nursing implemented systems of formally recognising professional development, with the awarding of continuing education (CE) points. While professional development has always been a requirement of continuing practice, this process is becoming more formalised. On 1 July 2010 the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency came into being as a national health practitioner body. With this, a formal requirement for continuing education or professional development was mandated. The Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, a subgroup of the above agency, clearly identifies the standard for continuing professional development of nurses and midwives.62 In New Zealand there is an expectation that a minimum of 60 hours professional development and 450 hours of clinical practice will be undertaken over a three-year period for the purposes of registration renewal.63

Conversely, North American nursing associations have for many years had formal programs for recognising continuing education and awarding CE points. These CE points have often been required to support continued registration. This concept has subsequently been implemented in the UK and Europe.64

Risk Management

Managing risk is a high priority in health, and critical care is an important risk-laden environment in which the manager needs to be on the lookout for potential error, harm and medico-legal vulnerability. The recent Sentinel Events Evaluation (SEE) study65 has given an indication of this risk for critical care patients. The SEE study was a 24-hour observational study of 1913 patients in 205 ICUs worldwide, which identified 584 errors causing harm or potential harm to 391 patients. The SEE authors concluded there was an urgent need for development and implementation of strategies for prevention and early detection of errors.65 A second study by the same team specifically targeted errors in administration of parenteral drugs in ICUs.66 In this study 1328 patients in 113 ICUs worldwide were studied for 24 hours; 861 errors affecting 441 patients occurred, or 74.5 parenteral drug administration errors per 100 patient days. The authors concluded that organisational factors such as error reporting systems and routine checks can reduce the risk of such errors.66

What is more alarming is that many health practitioners do not acknowledge their own vulnerability to error. One study asked airline flight crews (30,000) and health professionals (1033 ICU/operating room doctors and nurses, of whom 446 were nurses) from five different countries a simple question, ‘Does fatigue affect your (work) performance?’, with fascinating results.67 Of those responding, the following replied in the affirmative to the question: pilots and flight crew, 74%; anaesthetists, 53%; surgeons, 30% (a figure for nurses’ responses to this question was not provided in the study). The study also found that only 33% of hospital staff thought errors were handled appropriately in their hospital and that over 50% of ICU staff found it hard to discuss errors.67

Negligence

1. The provider owed a duty of care to the recipient.

2. The provider failed to meet that duty, resulting in a breech of care.

3. The recipient sustained damages (loss) as a result.

4. The breech by the provider caused the recipient to suffer reasonably foreseeable damages.68

Negligence is a technical error that can be proved in a court, although it does not follow that a negligent person is incompetent; in fact, many clinicians and managers have probably been technically negligent, it’s just that their errors have yet to be discovered! When managing in this context, the best hope is that the frequency of errors or negligent actions will be reduced by putting into place systems that prevent such errors from occurring.66

The Role of Leadership and Management

Managers must also be leaders, and the need to have good leaders and managers is as relevant to critical care as it is to any other business or clinical entity. Research on organisational structures in ICUs across the USA in the 1980s69 and 1990s70 demonstrated the important role leadership plays in patient care in the ICU. Using APACHE scoring, organisational efficiency and risk-adjusted survival were measured. High-performing ICUs demonstrated that actual survival rates exceeded predicted survival rates.

Further investigation and analysis of the higher-performing units noted that these units had well-defined protocols, a medical director to coordinate activities, well-educated nurses and collaboration between nurses and doctors.69 Clear and accessible policies and procedures to guide staff practice in the ICU setting were also highlighted.69 These need to be in written form, simple to read and in a consistent format, evidence-based, easy to understand and easy to apply. Box 2.3 shows a possible format for clinical policies and protocols.

The latter study showed similar characteristics: they had a patient-centred culture, strong medical and nursing leadership, effective communication and coordination, and open and collaborative problem solving and conflict management.70 One cannot underestimate the value of strong, dedicated and collaborative leadership from managers as the key to organisational success in the critical care setting. (See Chapter 1 for a discussion of leadership.)

Managing Injury: Staff, Patient or Visitor

For families and patients, an injury can be physical, such as a drug error or an iatrogenic infection; however, the injury can also be non-physical, as with complaints about lack of timely information, misinformation or rudeness of staff. In all circumstances a manager needs to intervene proactively to minimise or contain the negativity or harm felt by the ‘victim’. Regardless of the cause of the injury, the principles governing good risk management are common to many situations and are summarised in Box 2.4.

Box 2.4

Defensive principles to minimise risk after an incident (patient or staff)21

• Those persons encouraged to participate in decision making are more inclined to ‘own’ the decisions made; therefore, involve them in deciding how the issue is to be tackled and help to make the expectations realistic.

• Education of the person in the various aspects of the incident/activity will reduce fear and anxiety.

• Explain the range of possible outcomes and where the affected person is currently situated on that continuum.

• Provide frequent and accurate updates on the person’s situation and what is being done to improve that situation.

• Maintain a consistent approach and as far as possible the same person should provide such information/feedback.

If an incident does occur, it is always prudent to document the event as soon as possible afterwards and when it is safe to do so. The clinician who discovers and follows up an incident must document the event, asking the questions that a manager, family member, police officer, lawyer or judge might wish to ask. The written account provided soon after the event or incident by a person closely involved in, or witness to it, will form a very important testimonial in any subsequent investigation (Table 2.6).

TABLE 2.6 Key points when documenting an incident in a patient’s file notes21

| Question | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Where did the incident occur? | For example, bedside, toilet, drug room |

| Were there any pre-event circumstances of significance? | For example, short-staffed, no written protocol |

| Who witnessed the event? | Including staff, patient, visitors |

| What was done to minimise negative effects? | For example, extra staff brought to assist, slip wiped up, sign placed on front of patient chart warning of reaction/sensitivity etc |

| Who in authority was notified of the incident? | Involving a senior, experienced manager/authority should help expedite immediate and effective action. |

| Who informed the victim of the event? What was the victim told? What was the response? | Clear, concise and non-judgmental explanations to victim or representative are necessary as soon as possible, preferably from a credible authority (manager/director). |

| What follow-up support, counselling and revision occurred? | This is important for both victim and perpetrator; ascertain when counselling occurred and who provided it. |

| What review systems were commenced to limit recurrence of the event? | Magistrates and coroners in particular want to know what system changes have occurred to limit the recurrence of the event. |

Contemporary wisdom in modern health agencies advocates open disclosure: telling the truth to the patient or family about why and how an adverse event has occurred.71,72 This practice may be contrary to informed legal advice and may not preclude legal action against the staff or institution.73–75 However, openly informing the patient/family of what has occurred can regain trust and respect, and may help to resolve anger and frustration as well as to educate all concerned in how such events can be prevented in the future, a right for which many consumer advocates are now lobbying.76

The process of root cause analysis (RCA) can assist the team to explore in detail the sequence of events and system failures that precipitated an incident and help to inform future system reforms to minimise harm. An RCA is a generic method of ‘drilling down’ to identify hospital system deficiencies that may not immediately be apparent, and that may have contributed to the occurrence of a ‘sentinel event’. The general characteristics of an RCA are that it:77

Contingency Plans and Rehearsal

In addition to written policies and protocols, and as well as having well-educated clinical staff, it is always advisable to have back-up systems in place, especially for major and rare events that may require rapid management and coordinated responses. Ryan and MacLochlainn suggest the following:78

• a senior manager rostered on call and accessible for advice 24/7

• training of managers (not just clinicians) to know how to respond to crises and incidents

• current and easy-to-find policies and protocols, with specific information for a manager

• rehearsal of major and rare but foreseeable events, such as power outage, external disaster and mass casualty influx, and unit evacuation (these can be performed as simulated events or ‘tabletop’ exercises, where people describe how they would respond and coordinate the activity without actually demonstrating or implementing their decisions)

• peer support programs and training of peers, which can be informal, where colleagues debrief others who have had traumatic or confronting experiences (e.g. a difficult resuscitation, an aggressive or violent attack or a major personal trauma such as a personal family tragedy); however, there is growing evidence of the value of a more formalised system of peer support, where staff volunteer to make themselves available for training and to provide assistance and a listening ear to a colleague in need. In more complex cases, peers may suggest that the staff member seek professional counselling but can still make themselves available as peer support if desired by the affected staff member.

Measures of Nursing Workload or Activity

Several workload measures79–86 have been developed in an attempt to capture the complexity and diversity of critical care nursing practice (see Table 2.7 for common instruments). Some hospitals use an electronic care plan with activity timings to calculate nursing time and workload. An Australian instrument, the critical care patient dependency tool (CCPDT),83 was developed to measure nursing costs in the ICU and is still used in some units to document workload,87 although no further validation studies have been published since the original research in 1993. The most common instruments used in clinical practice and research are variants of the therapeutic intervention scoring system (TISS) and the Nursing Activity Scale (NAS) (see Tables 2.7 and 2.8).

| Nursing activities score | Points |

|---|---|

| NURSING ACTIVITIES | |

| 1. Monitoring and titration | |

| a. Hourly vital signs, regular registration and calculation of fluid balance | 4.5 |

| b. Present at bedside and continuous observation or active for ≥2 h in a shift, for reasons of safety, severity, or therapy (e.g. non-invasive mechanical ventilation, weaning procedures, restlessness, mental disorientation, prone position, donation preparation and administration of fluids or medication, assisting specific procedure) | 12.1 |

| c. Present at bedside and active for 4 h or more in any shift for reasons of safety, severity, or therapy (see 1b) | 19.6 |

| 2. Laboratory, biomedical and microbiological investigations | 4.3 |

| 3. Medication, vasoactive drugs excluded | 5.6 |

| 4. Hygiene procedures | |

| a. Performing hygiene procedures such as dressing of wounds and intravascular catheters, changing linen, washing patient, incontinence, vomiting, burns, leaking wounds, complex surgical dressing with irrigation, or special procedures (e.g. barrier nursing, cross-infection-related, room cleaning after infections, staff hygiene) | 4.1 |

| b. The performance of hygiene procedures took >2 h in any shift | 16.5 |

| c. The performance of hygiene procedures took >4 h in any shift | 20.0 |

| 5. Care of drains, all (except gastric tube) | 1.8 |

| 6. Mobilisation and positioning, including procedures such as turning the patient, mobilisation of the patient, moving from bed to a chair and team lifting (e.g. immobile patient, traction, prone position) | |

| a. Performing procedure(s) up to 3 times per 24 h | 5.5 |

| b. Performing procedure(s) more frequently than 3 times per 24 h, or with two nurses | 12.4 |

| c. Performing procedure with three or more nurses, any frequency | 17.0 |

| 7. Support and care of relatives and patient, including procedures such as telephone calls, interviews, counselling; often the support and care of either relatives or patient allow staff to continue with other nursing activities. | |

| a. Support and care of either relatives or patient requiring full dedication for about 1 h in any shift such as to explain clinical condition, dealing with pain and distress, and difficult family circumstances | 4.0 |

| b. Support and care of either relatives or patient requiring full dedication for 3 h or more in any shift, such as: death, demanding circumstances (e.g. large number of relatives, language problems, hostile relatives) | 32.0 |

| 8. Administration and managerial tasks | |

| a. Performing routine tasks such as: processing of clinical data, ordering examinations, professional exchange of information (e.g. ward rounds) | 4.2 |

| b. Performing administration and managerial tasks requiring full dedication for about 2 h in any shift such as: research activities, protocols in use, admission and discharge procedures | 23.2 |

| c. Performing administrative and managerial tasks requiring full dedication for about 4 h or more of the time in any shift such as a death and organ donation procedures, coordination with other disciplines | 30.0 |

| VENTILATORY SUPPORT | |

| 9. Respiratory support: any form of mechanical ventilation/assisted ventilation with or without PEEP, spontaneous breathing with or without PEEP, with or without endotracheal tube supplementary oxygen by any method | 1.4 |

| 10. Care of artificial airways: endotracheal or tracheostomy cannula | 1.8 |

| 11. Treatment for improving lung function: thorax physiotherapy, incentive spirometry, inhalation therapy, intratracheal suctioning | 4.4 |

| CARDIOVASCULAR SUPPORT | |

| 12. Vasoactive medication, disregard type and dose | 1.2 |

| 13. Intravenous replacement of large fluid losses, fluid administration >83 L/m/day | 2.5 |

| 14. Left atrium monitoring: pulmonary artery catheter with or without cardiac output | 1.7 |

| 15. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation after arrest, in past period of 24 h | 7.1 |

| RENAL SUPPORT | |

| 16. Haemofiltration techniques, dialysis techniques | 7.7 |

| 17. Quantitative urine output measurement (e.g. by indwelling catheter) | 7.0 |

| NEUROLOGICAL SUPPORT | |

| 18. Measurement of intracranial pressure | 1.6 |

| METABOLIC SUPPORT | |

| 19. Treatment of complicated metabolic acidosis/alkalosis | 1.3 |

| 20. Intravenous hyperalimentation | 2.8 |

| 21. Enteral feeding through gastric tube or other gastrointestinal route | 1.3 |

| SPECIFIC INTERVENTIONS | |

| 22. Specific intervention in the ICU: endotracheal intubation, insertion of pacemaker, cardioversion, endoscopies, emergency surgery in the previous 24 h, gastric lavage; routine interventions without direct consequences to the clinical condition of the patient (e.g. X-ray, ECG, echo, dressings, insertion of CVC or arterial catheters) not included | 2.8 |

| 23. Specific interventions outside the ICU; surgery or diagnostics procedures | 1.9 |

| TOTAL NURSE ACTIVITIES SCORE |

TABLE 2.7 Common ICU nursing workload instruments

| Instrument | Components | Scoring/interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| TISS 197488, 198384 (USA) | 5788/7684 nursing activities related to therapeutic interventions; 0–4 points per variable | Most ICU patients: 10–60 points Acuity: class IV (≥40 points); III (20–39); II (10–19); I (<10) |

| UK ICS 198385, 200386 | 4 levels of care, with qualitative assessment of organ systems | 0 = routine ward care 1 = ward care supported by critical care team 2 = support and monitoring of single organ dysfunction/failure 3 = complex support and monitoring of multiple organ dysfunction/failure |

| OMEGA 199082 (France) | 47 therapeutic activities | Classified into 3 levels according to frequency |

| TISS-28 199679,89 (Europe) | 28 in 7 categories; points vary per item (0–8) | 46 points = 1 : 1 nursing/shift 23 points = HDU patient (1 : 2 staff-to-patient ratio) |

| NEMS 199780 (Europe) | 9 categories with varied points per item (3–12): basic monitoring, intravenous medication, mechanical ventilation, supplementary ventilatory care, single/multiple vasoactive medications, dialysis, interventions in/outside ICU | Equivalent scores to TISS-28; lack of discrimination limits use in predicting or calculating workload at the individual patient level |

| CCPDT 199683 (Australia) | 7 categories scored 1–4 points: (a) hygiene, mobility, wound care; (b) fluid therapy, intake and output, elimination; (c) drugs, nutrition; (d) respiratory care; (e) observations, monitoring, emergency treatment; (f) mental healthcare, support; (g) admission, discharge, escort | 4 levels of nursing time per shift: A = ≤10 points = <8 hours B = 11–15 points = 8 hours (1 : 1 ratio) C = 16–21 points = 9–16 hours D = >22 points = >16 hours (2 : 1 ratio) |

| NAS 200381 (Europe/multinational validation) | 23 items (5 with sub-items); varied points per item (1.3–32) (see Table 2.8 for details) | Measures calculated percentage of nursing time (in 24 hours) on patient-level activities; 100% = 1 nurse per shift |

Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System

The therapeutic intervention scoring system (TISS)88 was initially developed to measure severity of illness and related therapeutic activities, but has been widely used as a proxy measure of nursing workload in the ICU.89 One of the primary uses was to aid quantitative comparison between patients in order to allocate resources, with ongoing daily measurements giving an indication of patients’ progress. The original TISS had a number of areas for scoring, including patient care and monitoring, procedures, infusions and medications, and cardiopulmonary support. Points assigned to specific interventions ranged from 1 to 4 for a 24-hour period. A higher score signified a greater therapeutic effort. Several revisions and variants of TISS have been developed in Europe, including TISS-2879 and the nine equivalents of nursing manpower (NEMS).80,90

TISS-2879 was refined to be a more user-friendly instrument, with similar precision to measure nursing workload, staffing requirements and costing, and to differentiate between ICU and HDU patients.91 This simplified version of 28 items is divided into basic activities (including monitoring and medications), ventilatory support, cardiovascular support, renal support, neurological support, metabolic support and specific interventions. The score range is from 1 to 8, with an ICU-type patient expected to score over 40 points. It was estimated that a critical care nurse is able to provide 46 TISS-28 points per shift, with a score <10 signifying a ward patient, 10–19 an HDU-type patient, and >20, an HDU/ICU level.79 Most studies report mean daily TISS scores (e.g. 23 [range 14–35],92 36 [range 29–49]93 and 21 [±12]94). Such diversity in scores reflects a range in acuity of patients. Total ICU admission TISS scores are also occasionally reported.95,96 Importantly, the incidence of mortality at hospital discharge was higher in patients discharged from an ICU with a TISS of >20 points than in those with a TISS of <10 points (21% versus 4%).97 TISS was not, however, developed as a predictive tool – rather as a record of the level of nursing intervention required. One study noted that patients with longer ICU stays and worse quality-of-life (QOL) outcomes did not have the increase in resource consumption that would have been predicted, as reflected by their TISS.94 A number of direct-care nursing activities were not captured by TISS-28 (e.g. hygiene, activity/movement, information and emotional support), and a revised instrument, the nursing activity scale, was developed to address those limitations.81

Management of Pandemics

Intensive care beds and their associated resources (equipment and staffing) are finite resources and an organisational response is required to maximise potential ICU capacity. Lessons can be learnt from the global H1N1 pandemic in 2009. The knowledge gained from this experience clearly identifies the need to plan for the potential increased demand on critical care services.98 While it is beyond the scope of this chapter to cover this subject comprehensively, the aim is to outline briefly the areas for further examination, touching on the concept of the development of a surge plan.

In earlier experience98–102 the key role that critical care units have to play in an organised response to a pandemic, particularly an airborne one such as influenza, has been demonstrated, as has the reality that critical care units have been more severely affected than other clinical areas of a hospital. Demand for these services will, at these times, exceed normal supply.

Development of A Surge Plan

Hota et al.98 describe the preparations for a surge to service under the three headings ‘Staff, Stuff and Space’. The resources required will be examined under these headings.

Staff

The ability to staff a potentially expanded critical care bed base should examine the following:

• staff with critical care skills who do not currently work in this area

• staff from other areas with critical care based skills, such as recovery, anaesthetics, coronary care

• provision of training and education to support less experienced staff

• development of critical care nursing teams in which critical care expertise is spread across the teams to manage the patient load appropriately, i.e. in satellite units

• planning for critical care staff sick leave

• provision to redeploy pregnant staff

• provision of training and education of all staff to avoid panic and concern, for example, domestic and catering staff.

Stuff

• Ensure supplies of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

• Develop plans/policies for the rational use of PPE.

• Ensure supplies, and access to supplies, of required medications.

• Plan ability to boost ventilator capacity, such as with increased use of BiPAP or accessing state emergency stockpile.

Space

• Explore the ability of local private hospitals to assist with service provision for non-deferrable surgical cases.

• Identify alternative clinical areas within the hospital that may provide additional critical care beds as a satellite unit, such as recovery and coronary care.

• Triaging access to limited ventilation and/or critical care resources.100,103

Summary

Case study

Among other things you must consider the following tasks and make recommendations to the director of nursing of St Mary MacKillop’s Hospital (see Learning activities 1–4). Utilise information contained in this chapter to inform your work and recommendations.

Learning activities

Learning activities 1–4 relate to the case study.

1. Calculate the staffing numbers in FTEs that you will require in the first instance and then when fully functional. Determine the estimated cost of fully staffing the unit to your satisfaction, including productive and non-productive FTEs.

2. List the standard clinical equipment that you will require for each functional bed area, and estimate the cost of this equipment.

3. List the one-off clinical equipment items that will be required for the unit (i.e. the central monitor, ECG machines, bronchoscopes). Determine how many of each you will need in the first instance and how many you will need when the ICU is fully functional. Determine the estimated cost of the total equipment purchase to fully establish the 20-bed unit.

4. Choose one of the major equipment items that you have identified in question 3 and write a business case to support its purchase.

5. Imagine that the hospital wants to open all 20 beds but provides you with only enough funding to cover 80% of your total staffing and equipment needs, as determined in 1, 2 and 3 above. Your task is to compromise where you can to make staffing and equipment as efficient as possible on a budget that is 80% of that requested in the above questions. Explain the reductions you believe you can afford to make in staffing and equipment purchases. How many beds do you think you can safely maintain open on this budget?

6. Identify a new service that may be required in your healthcare setting (e.g. the provision of neurosurgery/cardiothoracic surgery/hyperbaric chamber) and undertake a cost–benefit analysis of providing this service to your community.

7. Identify a piece of equipment or new product that your unit is considering for purchase and undertake a product evaluation to determine its cost-effectiveness.

8. Develop a surge plan for your facility to accommodate an increase in demand for critical care beds. In your plan identify all resources that could be redirected to facilitate the implementation of this plan.

Ettelt S, Nolte E. Funding intensive care: approaches in systems using diagnosis-related groups. http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/2010/RAND_TR792.pdf.

How to write a business case template. http://www.ehow.com/how_4966927_write-business-case-template.html.

Medical Algorithms Project website. http://www.medal.org/visitor/login.aspx.

Tasmanian Government business case (small) template and guide. http://www.egovernment.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/word_doc/0013/15520/pman-temp-open-sml-proj-bus-case.doc.

University of Queensland ITS business case guide and template. http://www.its.uq.edu.au/docs/Business_Case.doc.

Durbin CG. Team model: advocating for the optimal method of care delivery in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(3Suppl):S12–S17.

Grover A. Critical care workforce: a policy perspective. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(3Suppl):S7–11.

Kirchhoff KT, Dahl N. American Association of Critical-Care Nurses’ national survey of facilities and units providing critical care. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15:13–28.

Narasimhan M, Eisen LA, Mahoney CD, et al. Improving nurse–physician communication and satisfaction in the intensive care unit with a daily goals worksheet. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15(2):217–222.

Parker MM. Critical care disaster management. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(3Suppl):S52–S55.

Robnett MK. Critical care nursing: workforce issues and potential solutions. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(3Suppl):S25–S31.

1 Galbally B. The planning and organisation of an intensive care unit. Med J Aust. 1966;1(15):622–624.

2 Fein IA, Fein SL. Utilisation and allocation of critical care resources. In: Civetta JM, Taylor RW, Kirby RR. Critical care. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:2009.

3 Lawson JS, Rotem A, Bates PW. From clinician to manager. McGraw-Hill: Sydney, 1996.

4 Wiles V, Daffurn K. There is a bird in my hand and a bear by the bed – I must be in ICU. Sydney: ACCCN; 2002.

5 Duckett StephenJ. Casemix funding for acute hospital inpatient services in Australia. Med J Aust. 1998;169:S17–S21.

6 Queensland Health. 2010–2011 Business rules & guidelines. Version 1.2. [Cited October 2010]. Available from www.health.qld.gov.au

7 Queensland Health. Business Rules and Guidelines 2009–2010 (appendices). [Cited October 2010]. Available from www.health.qld.gov.au

8 Department of Human Services, Victoria. Funding for intensive care in Victorian public hospitals. prepared March 2010. [Cited October 2010]. Available from http://www.health.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/429030/vic_icu_funding.pdf

9 NSW Health. NSW funding guidelines for intensive care services 2002/2003. http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/pubs/2002/pdf/icsfunding_0203.pdf, September 2002. [Cited October 2010]. Available from

10 NSW Health. NSW episode funding policy 2008/2009. Sydney: New South Wales Health; 2008.

11 Jackson T, Macarounas-Kirchmann K. Changing patterns of intensive care unit admission and length of stay in five Victorian hospitals. In: Selby-Smith C, ed. Economics and health: 1992. Melbourne: Monash University/NCHPE; 1993:149–164.

12 Ettelt S, Nolte E. Funding intensive care – approaches in systems using diagnosis-related groups. [Cited October 2010]. RAND, California. Available from http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/2010/RAND_TR792.pdf

13 Australian Health Workforce Advisory Committee. The critical care nurse workforce in Australia 2002. Sydney: AHWAC; 2002. p.1

14 Oye RK, Bellamy FE. Patterns of resource consumption in medical intensive care. Chest. 1991;99:685–689.

15 Crozier TME, Pilcher DV, et al. Long-stay patients in Australian and New Zealand intensive care units: demographics and outcomes. Crit Care Resusc. 2007;9(4):327–333.

16 Williams T, Ho KM, et al. Changes in case-mix and outcomes of critically ill patients in an Australian tertiary intensive care unit. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2010;38(4):703–709.

17 Rechner I, Lipman J. The costs of caring for patients in a tertiary referral Australian intensive care unit. Anaesth Intens Care. 2005;33(4):477–482.

18 Paz HL, Garland A, Weinar M, et al. Effect of clinical outcomes data on intensive care unit utilisation by bone marrow transplant patients. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(1):66–70.

19 Goldhill DR, Sumner A. Outcome of intensive care patients in a group of British intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1337–1345.

20 Strosberg MA, Weiner JM, Baker R. Rationing America’s medical care: the Oregon plan and beyond. Washington DC: The Brookings Institute Press; 1992.

21 Williams G. Quality management in intensive care. In: Gullo A, ed. Anaesthesia, pain, intensive care and emergency medicine. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2003:1239–1250.

22 Gan R. Budgeting. In: Crowther A, ed. Nurse managers: a guide to practice. Sydney: Ausmed, 2004.

23 Weaver DJ, Sorrells-Jones J. The business case as a strategic tool for change. JONA. 2007;37(9):414–419.

24 Paley N. Successful business planning – energizing your company’s potential. Thorogood: London; 2004.

25 Capezio PJ. Manager’s guide to business planning. Wisconsin: McGraw-Hill; 2010.

26 Australian Health Infrastructure Alliance (AHIA). Australasian health facility guidelines v. 3.0. http://www.healthfacilityguidelines.com.au/guidelines.htm, 2009. [Cited May 2010]. Available from

27 College of Intensive Care Medicine. Minimum standards for intensive care units. http://www.cicm.org.au/cmsfiles/IC-1%20Minimum%20Standards%20for%20Intensive%20Care%20Units.pdf, 2010. [Cited May 2010]. Available from

28 Association of Operating Room Nurses (AORN). Recommended practices for product selection in perioperative practice settings. AORN J. 2004;79:678–682.

29 Elliott D, Hollins B. Product evaluation: theoretical and practical considerations. Aust Crit Care. 1995;8(2):14–19.

30 Australian College of Critical Care Nurses (ACCCN). Position statement on intensive care nursing staffing. http://www.acccn.com.au/content/view/34/59, 2006. [Cited May 2010]. Available from

31 Australian College of Critical Care Nurses (ACCCN). Position statement on the provision of critical care nursing education. http://www.acccn.com.au/images/stories/downloads/provision_CC_nursing_edu.pdf, 2006. [Cited May 2010]. Available from

32 New Zealand Nurses Organisation: Critical Care Section (NZNO). Philosophy and standards for nursing practice in critical care, 2nd edn. Wellington: NZNO; 2002.

33 Clarke T, Mackinnon E, England K, et al. A review of intensive care nurse staffing practices overseas: what lessons for Australia? Aust Crit Care. 1999;12(3):109–118.

34 Martin J, Warne C, Hart G, et al. Intensive care resources and activity Australia and New Zealand 2005/2006. Melbourne: Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society; 2007.

35 Australian College of Critical Care Nurses (ACCCN). Position statement on the use of healthcare workers other than division 1 registered nurses in intensive care. Melbourne: ACCCN; 2006.

36 The World Federation of Critical Care Nurses (WFCCN). Declaration of Buenos Aires. Position statement on the provision of critical care nursing workforce. http://en.wfccn.org/pub_workforce.php, 2005. [Cited November 2005]. Available from

37 College of Intensive Care Medicine. Recommendations on standards for high dependency units seeking accreditation for training in intensive care medicine. http://www.cicm.org.au, 2010. [Cited May 2010]. Available from

38 Adomat R, Hewison A. Assessing patient category/dependence systems for determining the nurse/patient ratio in ICU and HDU: a review of approaches. J Nurs Manag. 2004;12:299–308.

39 Clinical Excellence Commission. Between the flags project: the way forward. http://www.cec.health.nsw.gov.au/files/between-the-flags/publications/the-way-forward.pdf, 2008. [Cited May 2010]. Available from

40 McGaughey J, Blackwood B, O’Halloran p, et al. Realistic evaluation of early warning systems and the acute life-threatening events – recognition and treatment training course for early recognition and management of deteriorating ward-based patients: research protocol. JAN. 2010;66(4):923–932.

41 Tait D. Nursing recognition and response to signs of clinical deterioration. Nurs Manag. 2010;17(6):31–35.

42 Cho SH, Hwang JH, Jaiyong K. Nurse staffing and patient mortality in intensive care units. Nurs Research. 2008;57(5):322–330.

43 Duffield C, Roche M, Diers D, et al. Staffing, skill mix and the model of care. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2242–2251.

44 Numata Y, Schulzer M, van der Wal R, et al. Nurse staffing levels and hospital mortality in critical care settings: literature review and meta-analysis. JAN. 2006;55(4):435–448.

45 Robinson S, Griffiths P, Maben J. Calculating skill mix: implications for patient outcomes and costs. Nurs Manag. 2009;16(8):22–23.

46 Flynn M, McKeown M. Nurse staffing levels revisited: a consideration of key issues in nurse staffing levels and skill mix research. J Nurs Manag. 2009;17:759–766.

47 Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Mattke S, et al. Nurse-staffing levels and the quality of care in hospitals. New Engl J Med. 2002;346:1715–1722.

48 Heinz D. Hospital nurse staffing and patient outcomes: a review of current literature. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2004;23(1):44–50.

49 Nursing and Midwifery Office. Enrolled nurse – critical care unit project. Sydney: NSW Health; 2009.

50 Duffield C, Roche M, O’Brien-Pallas L, et al. Glueing it together: nurses, their work environment and patient safety. http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/pubs/2007/pdf/nwr_report.pdf, 2007. [Cited May 2010] Available from

51 Beckman U, Baldwin I, Durie M, et al. Problems associated with nursing staff shortage: an analysis of the first 3600 incident reports submitted to the Australian incident monitoring study (AIMS-ICU). Anaesth Intens Care. 1998;26:396–400.

52 Morrison A, Beckmann U, Durie M, et al. The effects of nursing staff inexperience (NSI) on the occurrence of adverse patient experiences in ICUs. Aust Crit Care. 2001;14(3):116–121.

53 Martin J, Warne C, Hart G, et al. Intensive care resources and activity Australia and New Zealand 2005/2006. Melbourne: Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society; 2007.

54 Canadian Association of Critical Care Nurses (CACCN). Position statement: non-regulated health personnel in critical care areas. http://www.caccn.ca/en/publications/position_statements/ps1997.html, 1997. [Cited April 2010]. Available from

55 British Association of Critical Care Nurses (BACCN). Standards for nurse staffing in critical care. http://www.baccn.org.uk/downloads/BACCN_Staffing_Standards.pdf, 2009. [Cited April 2010]. Available from

56 Campolo M, Pugh J, Thompson L, et al. Pioneering the 12-hour shift in Australia: implementation and limitations. Aust Crit Care. 1998;11(4):112–115.

57 World Federation of Critical Care Nurses (WFCCN). Declaration of Madrid. Position statement on the provision of critical care nursing education. http://en.wfccn.org/pub_education.php, 2005. [cited April 2010]. Available from