Resection of Submucous Myoma

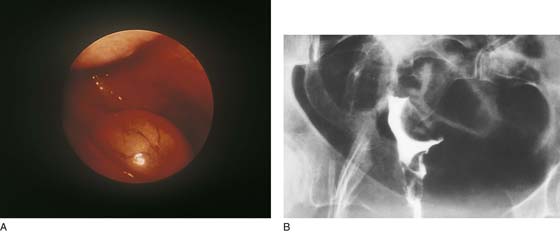

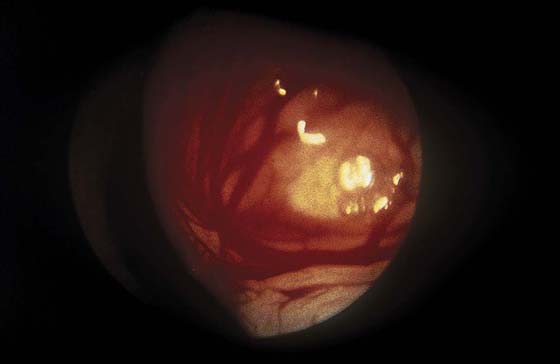

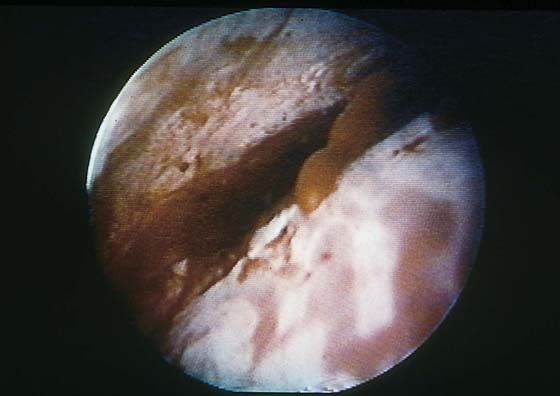

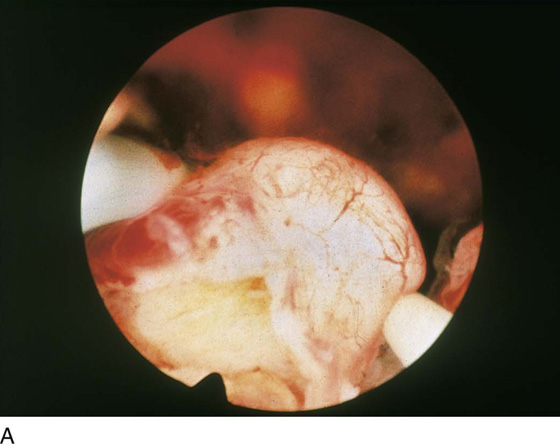

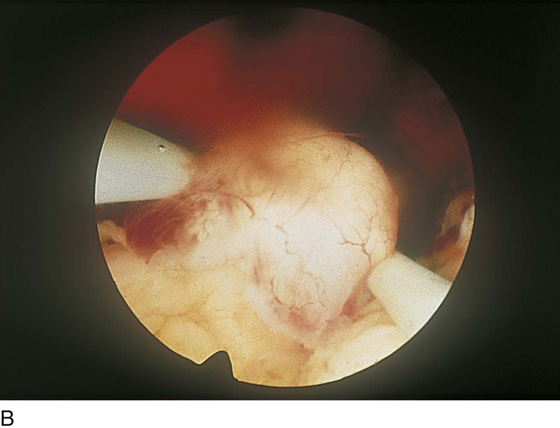

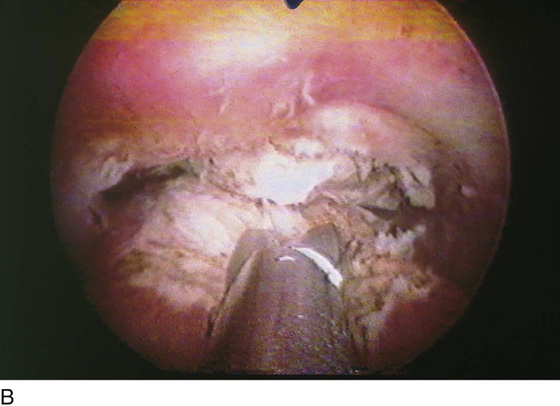

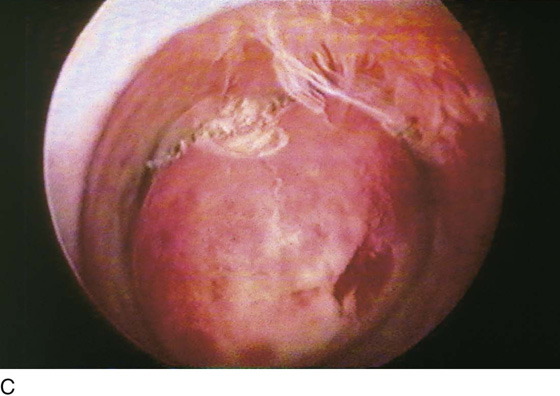

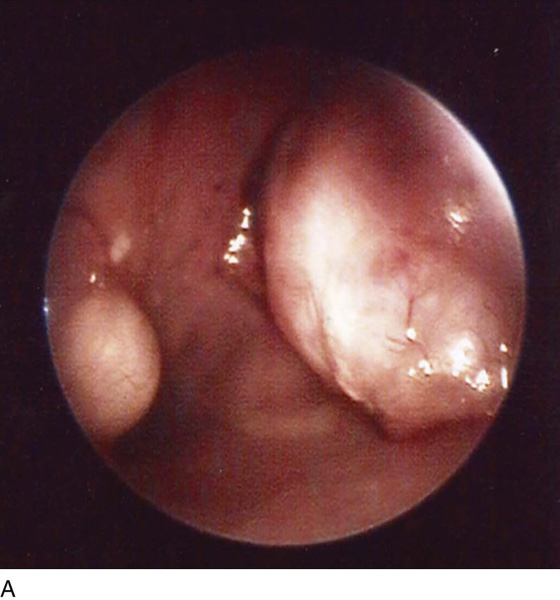

Although uterine myomata may occur at any location within the uterus, the submucous variety accounts for most clinical symptoms. The usual clinical presentation for these lesions includes heavy and prolonged bleeding. The diagnosis is made most commonly by diagnostic hysteroscopy and less commonly by radiographic imaging procedures (Fig. 111–1A, B). The hysteroscopic appearance of a submucous myoma is consistently recognizable. A rounded mass lesion is seen (Fig. 111–2). Myomata are white or pink (Fig. 111–3). Their contour may be spherical or hemispherical, and they always project into the uterine cavity. Close-up scrutiny reveals numerous thin-walled, sinusoidal vessels branching upon the surface. Areas of ecchymosis or adherent blood clots are commonplace (Fig. 111–4). If a viscid medium is used to distend the uterus, the actual site(s) of hemorrhage may be viewed as the blood spews from the ruptured, surface, sinusoidal vessel (Fig. 111–5).

The treatment of choice for a submucous myoma is hysteroscopic destruction, preferably by resection. Alternative treatments include myolysis utilizing laser fiber or bipolar needles, or arterial embolization performed by invasive radiology. The obvious advantages of hysteroscopic resection are that it is less invasive than radiologic embolization, which entails arteriography; additionally, the physical removal of the myoma provides a specimen for the pathologist. Although leiomyosarcoma is not common, it is a risk and is associated with the presence of what may appear to be an otherwise benign myoma.

Candidates for hysteroscopic treatment should be prepared with the intramuscular administration of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist (Lupron), 3.75 mg monthly for 3 months before the anticipated surgery. Lupron will reduce the size of the myoma, will reduce its vascularity, and will atrophy the surrounding endometrium. For large submucous myomata, the hysteroscopy should be accompanied by a simultaneous laparoscopy.

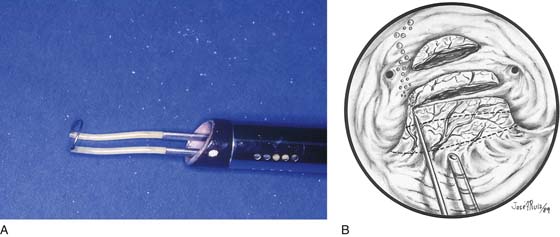

The patient is positioned as described in Chapter 106. The instruments of choice are the resectoscope fitted with a cutting-loop electrode, a fine electrosurgical needle, or a neodymium yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd-YAG) laser fiber (Fig. 111–6A, B). Most hysteroscopic surgeons will excise the myoma by shaving it with the resectoscope loop (see Fig. 111–6A). Therefore, a nonelectrolytic distending medium is required. Typically, the most appropriate medium in this case will be 5% mannitol. The medium is infused via tubing through the intake port of the operative sheath. Before the instrument is inserted, all the air is purged from the connecting tubing and the operating sheath. An endoscopic television camera is attached to the eyepiece of the optic, and the instrument is inserted transcervically into the uterine cavity under direct vision.

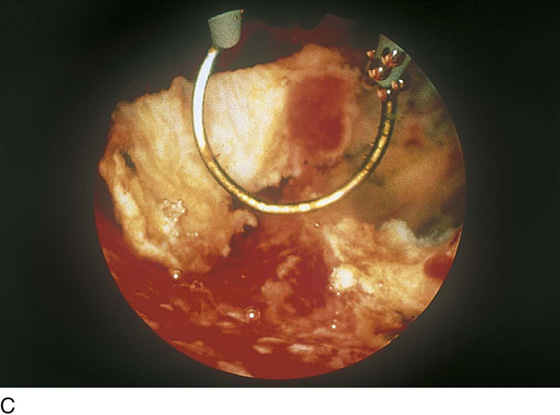

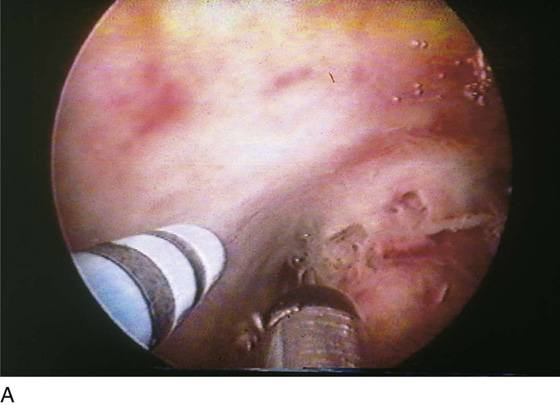

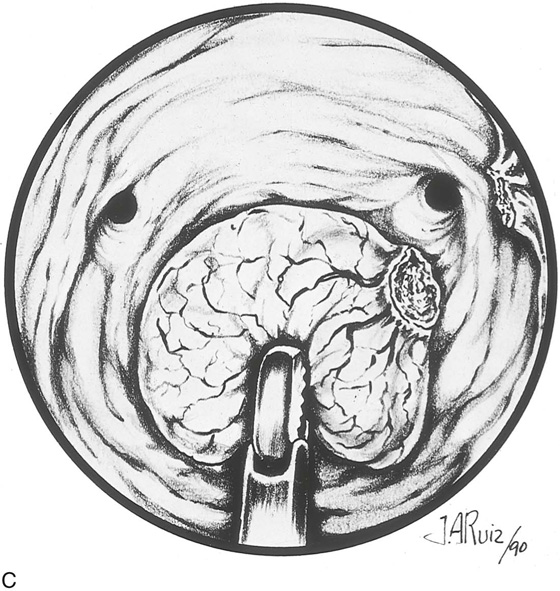

The myoma is located, and the cavity is flushed to remove blood and debris. The myoma is carefully mapped by circumnavigating around it with the hysteroscope. The pedicle of the myoma is identified. The relative width of the attachment is noted, as is its site of attachment. The uterine cornua and the tubal ostia are similarly located. The objective lens of the resectoscope is withdrawn away from the lesion to give the best panoramic view of the field (Fig. 111–7A). The cutting loop of the resectoscope is extended outward to the superior and posterior surfaces of the myoma, making contact with the lesion. The electrosurgical generator pedal activates the flow of electricity and cuts the myoma as the electrode is brought back toward the sheath of the resectoscope (Fig. 111–7B). The piece of tissue is shaken loose from the electrode and spins away into the uterine cavity. The loop electrode is again advanced and placed onto the myoma next to the place where the previous cut was made into its substance. The electrosurgical generator is again activated, and another piece of the myoma is sliced away. This process continues until the topmost part of the myoma has been reduced to a flat plateau (Fig. 111–7C). The next layer of the myoma is cut in a similar fashion; finally the entire mass has been reduced to a series of tissue chips, which are removed from the uterine cavity. Care is taken not to dig into the myometrium, that is, to reduce the projecting myoma only to the level of the surrounding tissue (Fig. 111–8).

Pressure is decreased by closing the outflow valve on the hysteroscope (resectoscope) sheath and partially closing the intake valve. This allows the surgeon to assess bleeding from the operative bed. Any brisk bleeding sites should be coagulated with a ball electrode. Finally, the cavity is flushed and re-distended to ensure complete integrity of the uterine wall.

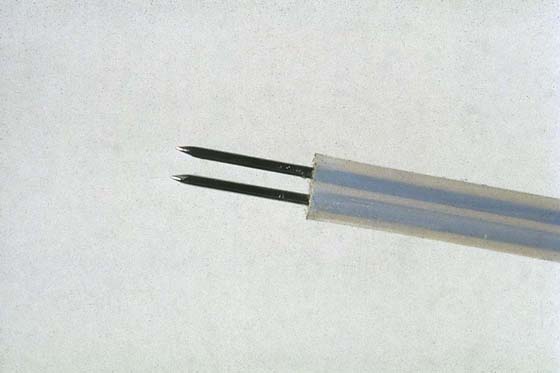

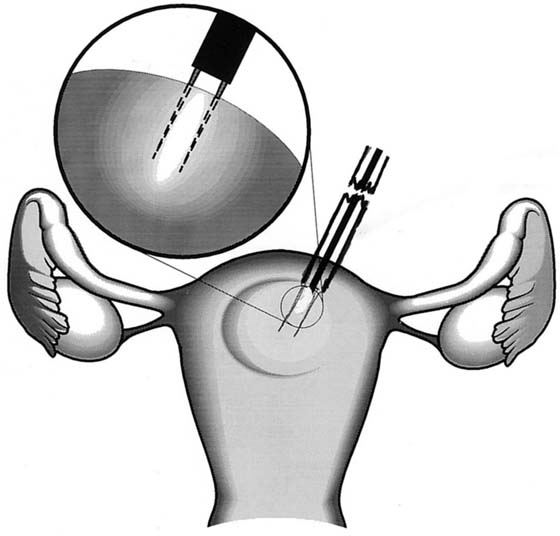

The technique of myolysis is relatively easy to perform. The instrument of choice is an Nd-YAG laser fiber or a hysteroscopic bipolar needle (Fig. 111–9). The end result of this procedure is equivalent to an arterial embolization. The myoma is identified and mapped. The needle or fiber is jabbed into the myoma to a depth of 3 to 4 mm, and the laser or electrosurgical energy is simultaneously activated (Fig. 111–10). This procedure is repeated 20 to 40 times or more to coagulate and destroy the interior of the myoma. The myoma is left in situ to die “on the vine.” The technique is enhanced by first coagulating the surface sinusoidal vessels. This technique diminishes bleeding from the surface of the myoma as the fiber or needle is withdrawn. At the terminus of the procedure, the myoma is studded with multiple blanched holes.

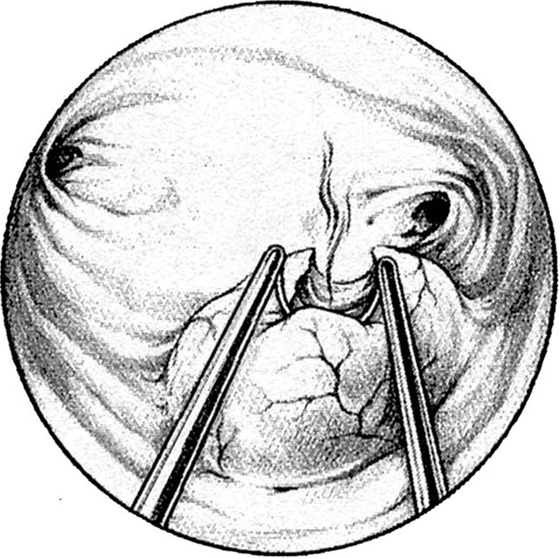

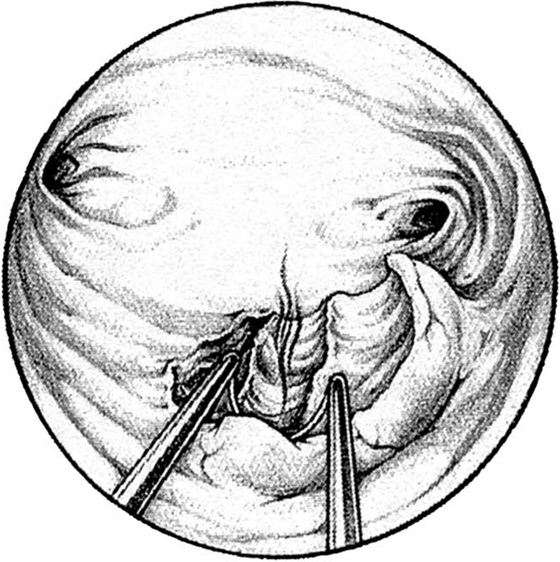

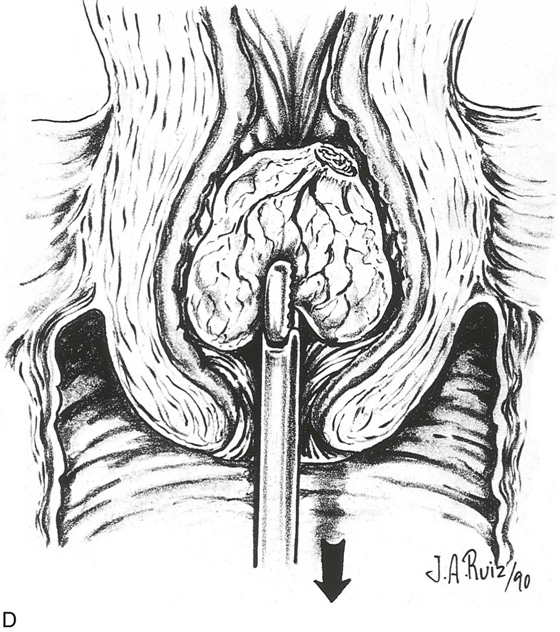

Pedunculated myomata with a narrow pedicle may be managed by cutting via a needle point electrode. After the myoma is mapped, the hysteroscope is insinuated between the myoma and the uterine wall immediately above the point of attachment of the pedicle to the uterine wall. The needle electrode is extended to make contact with the midportion of the pedicle (Fig. 111–11A). The electric current is activated as the entire hysteroscope is moved down, while the tip of the electrode incises the pedicle of the myoma. This may be repeated three or four times until the myoma is freed from its attachments to the uterine wall (Fig. 111–11B, C). The myoma is extracted by dilating the cervix and inserting a sponge forceps, which in turn grasps and compresses the myoma before withdrawing it via the dilated cervical canal. Alternatively, if the myoma is small (<2 cm) and the pedicle narrow, then scissors may be used to cut the myoma free (Fig. 111–12A through D).

FIGURE 111–1 A. Panoramic hysteroscopic view of a submucous myoma. Hysteroscopy is the most accurate method for making this diagnosis. B. Hysterogram shows a filling defect consistent with submucous myoma. The smooth contour favors the myoma diagnosis but is not precise.

FIGURE 111–2 The typical round appearance associated with some ecchymotic areas is diagnostic of a myoma with recent hemorrhage.

FIGURE 111–3 The surface vascular pattern is also characteristic of submucous myoma.

FIGURE 111–4 Close-up view of the surface vessels confirms their composition. The thin-walled and fragile sinusoidal channels are engorged with blood.

FIGURE 111–5 Eruption of one of these channels. The 32% dextran-70 (Hyskon) medium (which does not mix with blood) permits a clear view of the spontaneous hemorrhage.

FIGURE 111–6 A. The most commonly used tool to treat submucous myoma is the resectoscopic shaving-loop electrode. This thin wire develops very high power densities, thereby permitting rapid vaporization (cutting) of the tissue. B. The neodymium: yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd-YAG) laser fiber is an alternative technique for sectioning a submucous myoma.

FIGURE 111–7 A. This sequential hysterophotograph shows the resectoscope electrode extended behind but in contact with a posterior wall submucous myoma. B. The electric current is activated, and the loop electrode cuts into the myoma. Note the blood spray to the left as the electrode is drawn back toward the hysteroscope. C. Most of the myoma has been resected. A few “chips” of tissue are floating in the medium.

FIGURE 111–8 Schematic illustrating the events shown in Figure 111–7A through C. Note that the myoma is systematically shaved away until the surface is flush with the surrounding endometrium. It is not advisable to dig into the surrounding myometrium to extract that portion of the myoma within the uterine wall.

FIGURE 111–9 Double-prong, bipolar needle electrode. One needle is the active electrode; the other is the return (neutral) electrode. This 3-mm instrument is inserted through the operating channel of the hysteroscopic sheath.

FIGURE 111–10 Schematic view of myolysis. The bipolar needle jabs the myoma multiple times. Each jab is associated with coagulation of the interior of the myoma. Ultimately, the entire myoma is coagulated from within and undergoes necrosis and devascularization.

FIGURE 111–11 A. This large myoma is attached to the anterior uterine wall by a pedicle. A needle electrode contacts the right (patient) extreme of this attachment. B. The pedicle has been partially cut through with the electrode. It is now finished with hysteroscopic scissors. C. The myoma is completely detached and floats freely in the uterine cavity.

FIGURE 111–12 A. A small but well-defined submucous myoma. This has a rather broad-based (sessile) attachment to the uterine wall. An even myoma is seen on the opposite wall. B. A small myoma is attached to the left uterine wall by a narrow pedicle. The pedicle is cut under direct vision with hysteroscopic scissors. C. The myoma is grasped with alligator forceps. D. The myoma is delivered via a dilated cervix.