2 Researching a complex intervention

Introduction

It seems odd now, when we consider that the effect of acupuncture is at least partially mediated through the nervous system, that this stricture was widely applied within the physiotherapy profession. It can be argued that it was partly because, as the research techniques became more sophisticated and the randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) began to show negative (or, at any rate, less positive) results, physiotherapy practitioners lost some faith in the technique and were less prepared to tackle any condition not on the pain list or even on the National Institutes of Health list [1], although that did include conditions that would have been classified as neurological.

National Institutes of Health List 1998

A claim was made for promising results in the following conditions:

Research concentrated on the physiological effects mediated by the nervous system, with some of the early work by Andersson and Lundeberg [2–6] providing some answers. Their work highlighted the similarities between the physiological effects of acupuncture and the more familiar effects of exercise, reassuring physiotherapists that the results of their acupuncture treatment could be understood within their own profession, although in a limited context.

Some new thinking was required and, since physiotherapists were well versed in neurophysiology, clinical reasoning began to centre on that. Lynley Bradnam was probably the first to offer a useful structure to support clinical decisions and point choices [7–9]. She suggested that if the known pathology was carefully considered then the choice of appropriate points for musculoskeletal pains would automatically become easy. This approach overcomes the credibility gap often found when a therapist chooses points from a Western perspective but finds a need to extend or amplify the effects by reverting to poorly understood TCM choices, because the simple formulae do not offer much by way of progression when patient improvement slows or stalls. Once the physiological mechanisms are better understood, there is no conflict. This approach also serves as a useful foundation for clinical reasoning when moving beyond treating just pain and considering the wider implications of treating neurological patients.

Although generally less concerned with the specific application of acupuncture in neurology, medical doctors in the UK and around the world have begun to concentrate on what is termed Western medical acupuncture, claiming that acupuncture is increasingly understood through scientifically plausible mechanisms. White, in the journal Acupuncture in Medicine, states that there is ‘evidence from systematic reviews that acupuncture is superior to placebo for treating nausea, chronic back and knee pain, tension headache and postoperative pain’ but continues that now phase II studies to determine the optimal acupuncture treatment should be encouraged [10]. He emphasizes that, although acupuncture involves only minimal technology, there are infinite complexities and uncertainties about the mechanisms involved.

Western medical acupuncture is a therapeutic modality involving the insertion of fine needles. It is an adaptation of Chinese acupuncture using current knowledge of anatomy, physiology and pathology and the principles of evidence-based medicine. While Western medical acupuncture has evolved from Chinese acupuncture, its practitioners no longer adhere to concepts such as Yin/Yang and circulation of Qi, and regard acupuncture as part of conventional medicine rather than a complete ‘alternative medical system’. It acts mainly by stimulating the nervous system, and its known mode of action includes local antidromic axon reflexes, segmental and extrasegmental neuromodulation, and other central nervous system effects. Western medical acupuncture is principally used by conventional health practitioners, most commonly in primary care. It is mainly used to treat musculoskeletal pain, including myofascial trigger point pain. It is also effective for postoperative pain and nausea. Practitioners of Western medical acupuncture tend to pay less attention than classical acupuncturists to choosing one point over another, though they generally choose classical points as the best places to stimulate the nervous system. The design and interpretation of clinical studies is constrained by lack of knowledge of the appropriate dosage of acupuncture, and the likelihood that any form of needling used as a usual control procedure in ‘placebo-controlled’ studies may be active. Western medical acupuncture justifies an unbiased evaluation of its role in a modern health service [11].

Clinical reasoning and acupuncture

Evidence-based medicine

Evidence-based medicine is defined as ‘the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients’ [12]. It has been argued that evidence-based approaches represent a narrow reductionism that ignores clinical judgement and experience and encourages a slavish reliance on statistical methodology, in particular a dogmatic support of the RCT [13]. It is nonetheless essential that we attempt to use what is still considered best evidence, even though not all of the current research work is of compelling quality.

It is a truism that all medicine is now exhaustively researched before it is applied to a patient and the process for the discovery and subsequent release of new drugs tends to follow a well-worn pattern. The thrust of acupuncture research has been different to that for new drugs and treatments. This is generally because acupuncture is already in use. Indeed, it has been in use for at least 1000 years in parts of the world and shows no signs of dying out. This has been recognized by the World Health Organization, which has supported it in several ways, recommending minimum training standards, discussing terminology and assembling definitive point locations to make research methodologies more accurate [14]. Now, with definitive locations of acupuncture points agreed in the main by the major acupuncture nations, China, Korea and Japan, the possibility of having precisely repeatable treatment protocols incorporated into research projects is a real one [15]. This will naturally link in with the move to record and report all acupuncture intervention details in a scientific paper, as set out in the Standards for Reporting Interventions in Controlled Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA) guidelines [16].

Good reporting is essential and, in addition to the STRICTA guidelines, adherence to the advice given by the Consolidated Standards for Reporting of Trials (CONSORT) organization, particularly that for non-pharmacologic interventions [17], will assist in gaining and maintaining scientific credibility for all acupuncture trials.

Nonetheless, the early work done when introducing a new drug on to the market usually begins with an investigation into the mechanism, followed by studies set up to look at the initial effectiveness and, provided the results are promising, efficacy and then safety. The progression of acupuncture research has often appeared to be reversed because the most immediately important factor has been seen as safety, since it is already widely used. Initially, studies were set up to see how it was being used and whether there were associated risks [18, 19].

This has had an effect on the acceptance of acupuncture by the medical community at large. The two major studies published in 2001 [18, 19] were very positive and provided excellent confirmation of the safety of this intervention. A total of 66 000 treatment episodes in the two studies provided very few adverse events, ‘the most common minor adverse events being bleeding, needling pain, and aggravation of symptoms; however, aggravation was followed by resolution of symptoms in 70% of cases. There were 43 significant minor adverse events reported, a rate of 14 per 10 000, of which 13 (30%) interfered with daily activities’ [18]. No serious adverse events were reported in the study by MacPherson et al. either [19]. The results gave rise to the editorial comment in the British Medical Journal that: ‘While the risks of acupuncture cannot be discounted, it certainly seems, in skilled hands, one of the safer forms of medical intervention’ [20].

Sometimes this impression was produced by the fact that the acupuncture selected for the condition was hopelessly inadequate, consisting of few treatments or limited points. This arose when the researchers were not acupuncturists and had little understanding of the clinical application of the intervention under scrutiny. A study which unfortunately became a source of much amusement in acupuncture circles [21] claimed that acupuncture had no place in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. On careful reading, the intervention proved to have been a single acupuncture point, Liv 3, Taichong, used on five occasions and retained only for 4 minutes each time. This conformed to neither TCM nor Western medical good acupuncture practice. The paper was subsequently heavily criticized but the damage was done [22]. Appearing, as it did, in an influential medical journal, it probably set the use of acupuncture by physiotherapists in this field back by a good 10 years.

Currently there is an increase in research into the mechanisms, including much functional magnetic resonance imaging work examining the effect of acupuncture on the brain, principally by Napadow and his group [23, 24]. Langevin et al., working in parallel, investigated the effect of needle manipulation on connective tissue, looking for a mechanical effect [25].

This change in focus is partly because, as the research community has worked through this process, it has become plain that the entire mechanism is not yet understood. We have parts of the picture but there are still many questions to be asked of what is now recognized as a complex intervention. Also the important German RCTs (Modellvorhaben Akupunktur), where both the true acupuncture and the sham control showed significant effects over normal care, have emphasized the problem of finding an inert placebo for the complex intervention that is acupuncture [26].

It is clear that the traditional construction of an RCT requires the use of a placebo control in order to be considered as first-class evidence but it is debatable whether this is the most appropriate way to investigate an intervention like acupuncture. If we do not fully understand all the neural pathways and mechanisms, how can we be sure that any placebo has no effect? Some researchers are exploring this issue and their early work seems to indicate that there is an additional response in the brain to real acupuncture, as compared to the sham procedures [27]. The different strands for acupuncture research are shown in Table 2.1.

| Evidence | Sources |

|---|---|

| Patient’s expectations of positive acupuncture effect (response to non-invasive sham acupuncture) causes greater brain activation than no expectation of effect (response to skin prick) | Pariente et al. (27) |

| Brain activity in response to acupuncture is distinct from activity in response to sharp pain | Hui et al. (49) |

| Acupuncture-induced clinical improvements in chronic pain and carpal tunnel syndrome correlate with changes in brain activity | Harris et al. (50), Newberg et al. (51), Napadow et al. (52) |

| Whether traditional indications of acupuncture point function, e.g. improvement of sight or hearing, predict acupuncture-induced changes in specific brain regions, e.g. visual or auditory cortices, remains controversial; both positive and negative findings |

From Hammerschlag et al. (57).

Clinical reasoning supporting the use of acupuncture

The process of clinical reasoning as it pertains to everyday practice is rather more than the application of theory to practice. It is defined as a cognitive process of critical analysis and reflection that supports decision-making. The purpose of this process is the well-being of the patients. The treatments are tailored to meet their individual needs, skills and priorities. Applying treatments on the basis of diagnosis only is something done by ‘technicians’ while those engaging in clinical reflection in order to make techniques directly relevant to their clients’ lives are demonstrating ‘professionalism’ [28].

An integral part of this approach to therapies is the development and acquisition of treatment models and the following considerations will add up to a reasonable framework, applicable to most conditions, very close to that evolved by Bradnam [9].

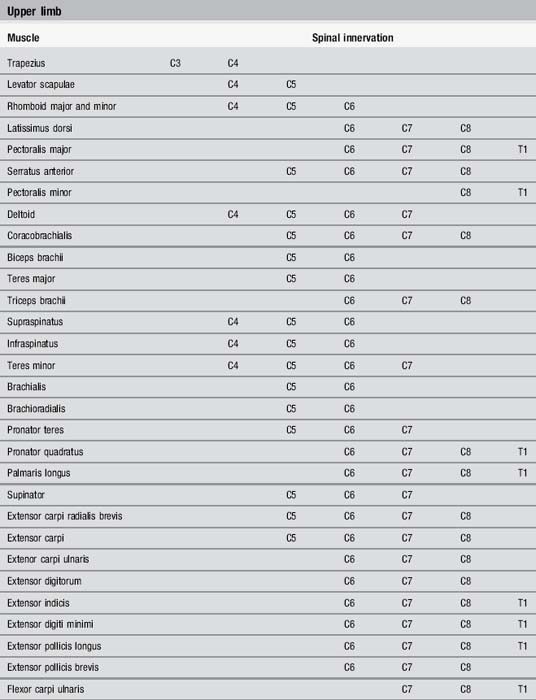

Since acupuncture is at least partly mediated by the nervous system it is important to ascertain the nerve supply to the painful site and the surrounding area. Acupoints are always associated with either cutaneous nerves or muscular nerves. Those close to muscular nerves tend to become tender more quickly than those associated with smaller nerves. As long as the practitioner is familiar with the muscular anatomy Table 2.2 indicates the associated nerve roots.

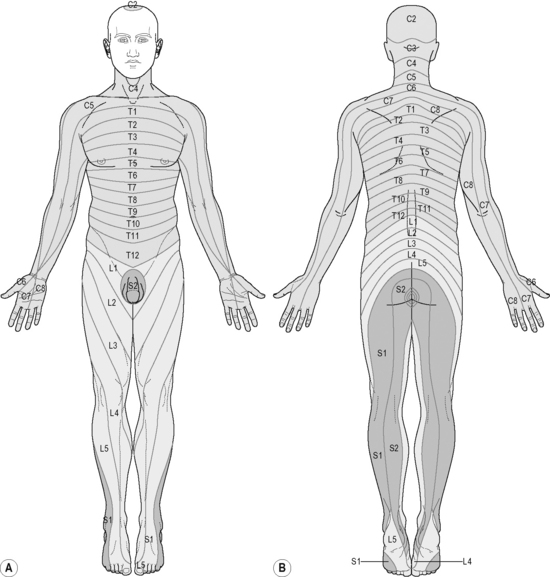

Linked with the nerve root are the dermatome, myotome and sclerotome sharing that supply. In order to locate dermatomes a body map will be useful but it must be remembered that the areas designated are not precise; small variations frequently occur (Figure 2.1). Nonetheless, when selecting points to needle, those within the segment will often have a more powerful effect. The mechanical needling of sensory nerve endings within a muscle also stimulates the corresponding motor neurons to send signals to relax the tight muscles. It appears that the mechanical movements of the needle in, out and/or rotatory are important. It pulls, moves and stretches all the broken or damaged fibres and leads to a softening of tissue around the needle [29]. This mechanical movement of connective tissue may have a far-reaching effect and has been extensively investigated by Langevin et al. [25].

Figure 2.1 • Adult dermatome patterns.

(Modified from Abrahams P, Hutchings R, Marks S. McMinn’s Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, 4th edn. London: Mosby, 1997.)

The approach to the orthodox healing process will vary according to the stage the patient has reached, and that with acupuncture is no different. Whether the situation is acute or chronic will influence the soft-tissue changes that may be present. Interestingly, this idea is closely mirrored within meridian acupuncture, where the activity of the Wei Qi is influenced by the duration of the problem and the involvement of the musculotendinous meridians [30].

Sympathetic or parasympathetic activity cannot be ignored and, before arriving at the nerve supply for the area, careful palpation is recommended. If the aim is to treat relatively superficial injuries, high-frequency, low-intensity acupuncture will aid blood flow to the area by reducing sympathetic tone [31].

If healing damaged tissue is the main aim of the treatment then maximizing local effects will be most important. This can be achieved in several ways but the simple insertion of the needle into the painful tissue remains the most direct. If underlying symptoms such as loss of sleep, anxiety and general loss of impetus for rehabilitation are to be treated then the picture becomes more complex and mostly supraspinal responses should be sought. There is now considerable support for the use of acupuncture in insomnia [32].

Neuronal correlates of acupuncture stimulation in the human brain have been investigated by functional neuroimaging. The preliminary findings suggest that acupuncture at analgesic points involves the pain-related neuromatrix and may have acupoint–brain correlation. Wu et al. [33] concluded that the hypothalamus–limbic system was significantly modulated by EA at acupoints rather than at non-meridian points, while visual and auditory cortical activation was not a specific effect of treatment-relevant acupoints and requires further investigation of the underlying neurophysiological mechanisms. Real EA elicited significantly higher activation than sham EA over the hypothalamus and primary somatosensory motor cortex and deactivation over the rostral segment of anterior cingulate cortex.

The only research we have to support this is that by Hsu et al., but the clear effects on the circulatory system demonstrated by BL 15 indicate that other Back Shu points may also be as useful [31]. The designated ‘big’ points on the hands and feet that have a strong effect on the hypothalamus and regulate autonomic flow can be incorporated. Ear points can also be used.

The distinction between TCM and scientific reasoning is diminishing year by year. The recent work by Dorsher et al. [34] indicating a 91% correlation between the distributions of known trigger point regions’ referred pain patterns and acupuncture meridians indicates that trigger points most likely represent the same physiological phenomenon as acupuncture points in the treatment of pain disorders. They state: ‘It is implausible that trigger point regions and classical acupuncture points would by chance correlate so strongly – anatomically, physiologically (referred-pain patterns and meridians), clinically in pain treatment, and clinically in treating somatovisceral disorders – unless they represented the same phenomenon.’

Problems with research protocols

A research methodology depends entirely on the correct question being asked and being answered in some way. With the historical difficulty within acupuncture of being able to define firstly the mechanism and secondly the complex nature of the intervention, placing this within the context of an RCT has been problematic [35]. A major step forward has been the recent publication of a textbook examining the problems associated with rigorous research into acupuncture [36].

Many of the key issues are discussed and the overwhelming conclusion reached is that acupuncture is not yet fully understood. It is a complex non-pharmacological intervention with many facets and does not fit easily into the conventional drug trial format. This problem has also been discussed in detail in a previous book [37] but the most frequent problem is that of finding an adequate control.

The sham needles, those with a shaft that collapses into the handle like a stage dagger, have some value but still excite the C or touch fibres when used [38]. Also the researchers cannot be unaware that these needles are being used; the technique requires some care to avoid dropping the needles or failing to keep them adequately stuck to the skin surface [39].

Ingenious new needles, designed to maintain operator blindness to those receiving the sham needle, are now available but not yet in widespread use [40, 41]. These involve insertion into some soft substance inside the opaque applicator tube for the sham needle while the real one will be longer and enter the tissues. Most acupuncturists are convinced they could tell the difference but more research needs to be done with this.

It is not really possible to indicate how much of the total effect may be represented by each of the components suggested in Table 2.3 but it is probable that spontaneous changes vary from condition to condition while the associated or context effects may vary depending on the type of consultation taking place. It is also probable that the practitioner is the most important variable [42]. Clearly where there is both an element of ritual and an extensive clinical interview, the placebo effect of the intervention will be substantially reinforced and may be both practitioner- and dose-dependent [43, 44].

Minimal acupuncture, frequently used as a control, has been shown to be an active placebo and far from inert in a physiological sense. While it is possible that the varying responses to ‘verum’ and sham acupuncture are dependent on the cause of the pain, there is enough doubt about the validity of sham needling to suggest that it may be unfair to judge the effect of acupuncture in this way [45]. Depending on the aetiology of the problem the response to acupuncture is varying. Lundeberg et al. recommend that the evaluated effects of acupuncture could be compared with those of standard treatment, also taking the individual response into consideration, before its use or non-use is established [46].

Table 2.4 gives an indication of the varieties of approach required if the investigation into any relatively unfamiliar treatment/intervention is to be comprehensive. Very few studies so far can be cited as excellent examples of any approach.

Table 2.4 Developing a framework to accommodate the complexities of investigating acupuncture

| Research phase | Usual methods |

|---|---|

RCT, randomized controlled trial.

After McIintyre (60).

Particular problems researching neurological conditions

Most neurological conditions – stroke, Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis (MS) – do not offer a complete recovery; indeed, some, like motor neurone disease, are progressive illnesses over short periods of time without any favourable outcome. These conditions have attracted a limited amount of research funding over the years but a lot of this has been supported by specific charities rather than major government initiatives. To be fair, stroke prevention has received a lot of support recently, linked as it often is with cardiovascular disease, but dealing with the sequelae of stroke is a lot less glamorous, with many variables to confound the outcomes. The NHS has funded one major study of acupuncture and stroke [47], but, with the exception of the study by Park et al. [48], most of the other work has been done abroad. The MS Society is often helpful, financing smaller projects, but the logistics of setting up a study with a reasonably homogenous group of subjects with comparable MS disabilities is daunting, with very large numbers required.

[1] NIH consensus development panel on acupuncture. Acupuncture. JAMA. 1998;280(17):1518-1524.

[2] Andersson S., Lundeberg T. Acupuncture from empiricism to science: functional background to acupuncture effects in pain and disease. Med Hypotheses. 1995;45(3):271-281.

[3] Andersson S. Physiological mechanisms in acupuncture. In: Hopwood V., Lovesey M., Mokone S., editors. Acupuncture and Related Techniques in Physiotherapy. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1997:19-39.

[4] Carlsson C. Acupuncture mechanisms for clinically relevant long-term effects. Acupunct Med. 2002;20(2–3):82-99.

[5] Lundeberg T. A comparative study of the pain alleviating effect of vibratory stimulation, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, electroacupuncture and placebo. Am J Chin Med. 1984;XII(1–4):72-79.

[6] Lundeberg T., Hurtig T., Lundeberg S., et al. Long term results of acupuncture in chronic head and neck pain. Pain Clinic. 1988;2(1):15-31.

[7] Bradnam L. A proposed clinical reasoning model for western acupuncture. New Zealand Journal of Physiotherapy. 2003;31(1):40-45.

[8] Bradnam L. A physiological underpinning for treatment progression of western acupuncture. Journal of Acupuncture Association of Chartered Physiotherapists. 2007:25-33.

[9] Bradnam L. A proposed clinical reasoning model for western acupuncture. Journal of the Acupuncture Association of Chartered Physiotherapists. 2007:21-30.

[10] White A. Editorial. Acupunct Med. 2009;27(1):1-2.

[11] White A. Western medical acupuncture: a definition. Acupunct Med. 2009;27(1):33-35.

[12] Sackett D.L., Rosenberg W.M.C., Muir Gray J.A. Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71-72.

[13] Ross E.G. If not evidence, then what? Or does medicine really need a base. J Eval Clin Pract. 2002;8(2):113-119.

[14] WHO Western Pacific Region. WHO Standard Acupuncture Point Locations. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008.

[15] Hopwood V. A new bronze man!. Journal of the Acupuncture Association of Chartered Physiotherapists. 2007:59-60.

[16] MacPherson H., White A.R., Cummings M., et al. Standards for Reporting Interventions in Controlled Trials of Acupuncture: the STRICTA recommendations. Acupunct Med. 2002;20(1):22-25.

[17] Boutron I., Moher D., Altman D.G., et al. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):295-309.

[18] White A., Hayhoe S., Hart A., et al. Adverse events following acupuncture: prospective survey of 32 000 consultations with doctors and physiotherapists. BMJ. 2001;323:485-486.

[19] MacPherson H., Thomas K., Walters S., et al. The York acupuncture safety study: prospective survey of 34 000 treatments by traditional acupuncturists. BMJ. 2001;323:486-487.

[20] Vincent C. The safety of acupuncture. BMJ. 2001;323:467-468.

[21] David J., Townsend S., Sathanathan R., et al. The effect of acupuncture on patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised, placebo-controlled crossover study. Rheumatology. 1999;38:864-869.

[22] Tukmachi E. Acupuncture and rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2000;39:1153-1165.

[23] Napadow V., Makris N., Liu J., et al. Effects of electroacupuncture versus manual acupuncture on the human brain as measured by fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp. 2004;24(3):193-205.

[24] Napadow V., Dhond R., Park K., et al. Time-variant fMRI activity in the brainstem and higher structures in response to acupuncture. Neuroimage. 2009;47:289-301.

[25] Langevin H.M., Bouffard N.A., Churchill D.L., et al. Connective tissue fibroblast response to acupuncture: dose-dependent effect of bidirectional needle rotation. J Altern Complement Med (New York, N Y). 2007;13(3):355-360.

[26] Cummings M. Modellvorhaben Akupunktur – a summary of the ART, ARC and GERAC trials. Acupunct Med. 2009;27(1):26-30.

[27] Pariente J., White P., Frackowiak R.S.J., Lewith G. Expectancy and belief modulate the neuronal substates of pain treated by acupuncture. Neuroimage. 2005;25(4):1161-1167.

[28] Richardson B. Professional development. 2 Professional knowledge and situated learning in the workplace. Physiotherapy. 1999;85:467-474.

[29] Ma Y.-T., Ma M., Cho Z.H. Biomedical Acupuncture for Pain Management. Elsevier (USA): St Louis, 2005.

[30] Pirog J.E. Meridian sinews and the treatment of musculoskeletal pain. The Practical Application of Meridian Style Acupuncture. 1996:219-239.

[31] Hsu C.C., Weng C.S., Liu T.S., et al. Effects of electrical acupuncture on acupoint Bl15 evaluated in terms of heart rate variability, pulse rate variability and skin conductance response. Am J Chin Med. 2006;34(1):23-26.

[32] Bosch P.M.P.C., van den Noort M.W.M. Schizophrenia, Sleep and Acupuncture. Göttingen: Hogrefe & Huber, 2008.

[33] Wu M., Sheen J., Chuang K., et al. Neuronal specificity of acupuncture response: a fMRI study with electroacupuncture. Neuroimage. 2002;16(4):1028.

[34] Dorsher P.T., Fleckenstein J. Trigger points and classical acupuncture points: part 3: relationships of myofascial referred pain patterns to acupuncture meridians. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Akupunktur. 2009;52(1):9-14.

[35] Hopwood V., Lewith G. Acupuncture trials and methodological considerations. Clinical Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine. 2003;3(4):192-199.

[36] MacPherson H., Hammerschlag R., Lewith G., et al. Acupuncture Research. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier, 2008.

[37] Hopwood V. Acupuncture trials and methodological considerations. Acupuncture in Physiotherapy. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann, 2004.

[38] Park J., White A., Stevinson C., et al. Validating a new non-penetrating sham acupuncture device: two randomised controlled trials. Acupunct Med. 2002;20(4):168-174.

[39] White P., Lewith G., Hopwood V., et al. The placebo needle, is it a valid and convincing placebo for use in acupuncture trials? A randomised, single-blind, cross-over pilot trial. Pain. 2003;106:401-409.

[40] Takakura N., Yajima H. A double-blind placebo needle for acupuncture research. Biomed Central. 2007:1-15.

[41] Takamura N. Not yet known. Medical Acupuncture. 2008;20(3):169-174.

[42] Paterson C., Dieppe P. Characteristic and incidental (placebo) effects in complex interventions such as acupuncture. BMJ. 2005;330:1202-1205.

[43] Kaptchuk T., Kelley J.M., Conboy L.A., et al. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ. 2008;336(7651):999-1003.

[44] Kaptchuk T.J., Stason W.B., Davis R.B., et al. Sham device v inert pill: randomised controlled trial of two placebo treatments. BMJ. 2006;332(7538):391-397.

[45] Lund I., Naslund J., Lundeberg T. Minimal acupuncture is not a valid placebo control in randomised controlled trials of acupuncture: a physiologist’s perspective. Chinese Medicine. 2009;4(1):1.

[46] Lundeberg T., Lund I., Sing A., et al. Is placebo acupuncture what it is intended to be? eCAM. 2009:nep049.

[47] Hopwood V., Lewith G., Prescott P., et al. Evaluating the efficacy of acupuncture in defined aspects of stroke recovery: a randomised, placebo controlled single blind study. J Neurol. 2008;255(6):858-866.

[48] Park J., White A.R., James M.A., et al. Acupuncture for subacute stroke rehabilitation. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2026-2031.

[49] Hui K.K., Liu J., Makris N., et al. Acupuncture modulates the limbic system and subcortical gray structures of the human brain: evidence from fMRI studies in normal subjects. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000;9(1):13-25.

[50] Harris R.E., Gracely R.H., McLean S.A., et al. Comparison of clinical and evoked pain measures in fibromyalgia. J Pain. 2006;7(7):521-527.

[51] Newberg A.B., Lariccia P.J., Lee B.Y., et al. Cerebral blood flow effects of pain and acupuncture: a preliminary single-photon emission computed tomography imaging study. J Neuroimaging. 2005;15(1):43-49.

[52] Napadow V., Kettner N., Liu J., et al. Hypothalamus and amygdala response to acupuncture stimuli in carpal tunnel syndrome. Pain. 2007;130:254-266.

[53] Cho Z.H., Chung S.C., Jones J.P., et al. New findings of the correlation between acupoints and corresponding brain cortices using functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(March):2670-2673.

[54] Li G., Liu H.L., Cheung R.T., et al. An fMRI study comparing brain activation between word generation and electrical stimulation of language-implicated acupoints. Hum Brain Mapp. 2003;18(3):233-238.

[55] Gareus I.K., Lacour M., Schulte A.C., et al. Is there a BOLD response of the visual cortex on stimulation of the vision-related acupoint GB 37? J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;15(3):227-232.

[56] Hu K.M., Wang C.P., Xie H.J., et al. Observation on activating effectiveness of acupuncture at acupoints and non-acupoints on different brain regions. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2006;26(3):205-207.

[57] Hammerschlag R., Langevin H., Lao L., et al. Physiologic dynamics of acupuncture: correlations and mechanisms. In: MacPherson H., Hammerschlag R., Lewith G., et al, editors. Acupuncture Research. Strategies for Establishing an Evidence Base. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2008:188.

[58] Hopwood V. Acupuncture in Physiotherapy. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann, 2004.

[59] Linde K. The specific placebo effect. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforchung Gesundheitsschutz. 2006;49(8):729-735.

[60] McIntyre M. Report to Ministers from the Department of Health Steering Group on the Statutory Regulation of practitioners of acupuncture, herbal medicine, traditional Chinese medicine and other traditional medicine systems practised in the UK. Annex 1. Aberdeen: Department of Health, 2008.