29.1 Research in children in the emergency department

Research science

Research question

A good study question should be:

Literature review and level of evidence

The literature review should provide the background to the study question. Literature databases like Pubmed, Medline, Google scholar internet search engines, EMBASE and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) are useful but may initially be overwhelming. Helpful starting points can be standard textbooks, the Cochrane library, a search of BestBets (www.bestbets.org), BMJ Clinical Evidence (http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com) and the assistance of a medical librarian.

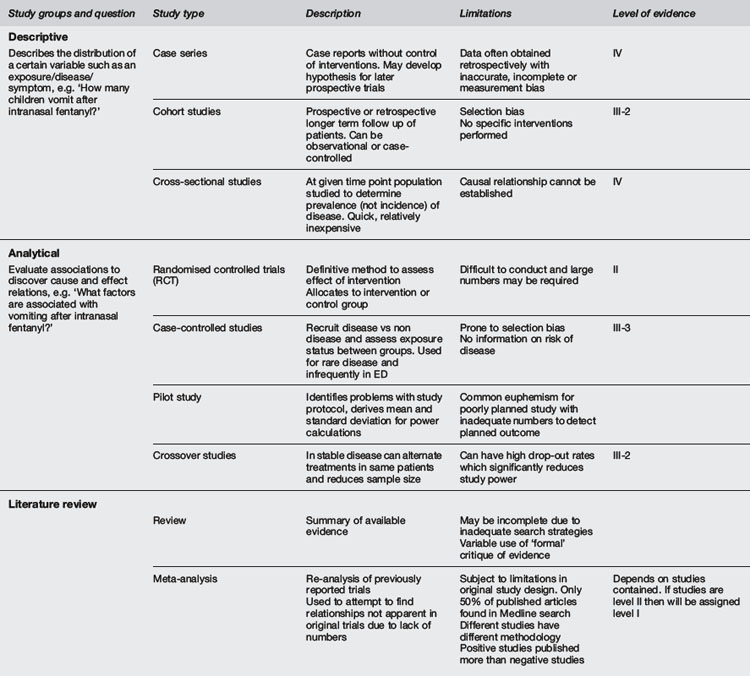

It is important to grade the importance of medical research evidence. There are many grading systems in use internationally. A commonly used example from National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) is shown in Table 29.1.1.1 Systematic reviews often use such a grading system as the basis for clinical management recommendations. The current standard of research evidence is the randomised clinical trial (RCT), and the highest level of evidence is meta-analysis of RCTs.

Adapted from NHMRC 1999.

The ethics of medical research

Following atrocities during the Second World War, written codes of medical ethics have been developed such as the Nuremberg Code2, the Declaration of Helsinki3 and the Belmont Report.4 The key principles developed in these documents still underpin most ethical guidelines.

Ethics of research involving children

There are in general four recruitment scenarios for children presenting to the ED who may be enrolled in research studies:5

Infants/toddlers without the capacity to understand or take part in discussions regarding a research project and whose parents/guardians are approached for consent.

Infants/toddlers without the capacity to understand or take part in discussions regarding a research project and whose parents/guardians are approached for consent. Children able to understand some relevant information and take part in limited discussion about the research, but whose consent is not required. Only parent/guardian consent is required for these children.

Children able to understand some relevant information and take part in limited discussion about the research, but whose consent is not required. Only parent/guardian consent is required for these children. Young people of developing maturity, able to understand the relevant information but whose relative immaturity means they remain vulnerable. The consent of these young people is required, but is not sufficient to authorise research, therefore requiring additional parent/guardian consent.

Young people of developing maturity, able to understand the relevant information but whose relative immaturity means they remain vulnerable. The consent of these young people is required, but is not sufficient to authorise research, therefore requiring additional parent/guardian consent.The practice and governance of research

Research documents

Research protocol

The key document for any study is the research protocol. It sets out why a trial should be run, acts as an operations manual and is the scientific design document for the trial. It is submitted to the HREC at the time of approval application along with the case report forms, patient information statement and consent form. The research protocol outlines in detail the research question being asked, background and rationale for the study, the design and methodology by which the question will be addressed, secondary objectives, primary and secondary outcomes, statistical considerations including sample size and power calculations. There should also be a discussion of any ethical implications of the study being undertaken. Templates for protocols can be found on the websites of a number of organisations such as the TGA.6

Patient information statement and consent form

In order to gain informed consent from a potential research participant, research projects require patient information statements in plain language and consent forms that must be approved by the ethics committee prior to their use. They are intended to outline the proposed study in language lay people can understand. Good patient information statements are difficult to write and poorly written ones may cause delays in obtaining ethics approval.7

Reporting guidelines

The reporting of clinical trials has a recommended, standardised approach, outlined by the CONSORT Statement, an evidence based format aimed at improving the quality and integrity of reporting for RCTs. CONSORT consists of a checklist and flow diagram for reporting a RCT.8 The flow diagram provides readers with a clear picture of the progress of all participants in the trial, from the time they are randomised until the end of their involvement. Both documents are also very helpful at the design stage of the trial and ensure that the research protocol is comprehensive and logical.

There are also a number of reporting guidelines for other types of studies. Information about reporting guidelines, including key checklists and flow diagrams, is listed at the EQUATOR website.9

Key regulatory documents

Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research11

All research in Australia must abide by the National Statement. The National Statement requires that research is conducted in accordance with the Australian Code of Conduct. However, this document does not provide an exhaustive description of how to conduct research. The TGA has published a more detailed document describing how research should be performed in Australia which in turn requires that researchers follow relevant sections of the ICH GCP.10

Project registration

Since July 2005 all clinical trials must be registered on a Clinical Trials Register before the enrolment of the first participant. The guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) state that any trial must be registered in order to be published in any of their comprehensive list of journals.12 The purpose of trial registration is a greater efficiency by reducing unnecessary duplication of research effort, better compliance, and a greater assurance that all clinical trials reports are reported, including those with negative results. There are several clinical trial registers worldwide including the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (ANZCTR).13

Multicentre research

Some of the difficulties in emergency research in children, such as the low frequency of major outcomes or limited applicability of findings, can be overcome by co-operating with other institutions. This recognition has led to a number of cooperative research networks, initially in North America (Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) and Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN)), in Australia and New Zealand (Paediatric Research in Emergency Departments International Collaborative (PREDICT)) and now also in Europe (Research in European Paediatric Emergency Departments (REPEDS)). These networks have increased the profile of paediatric emergency medicine, illustrated the similarities and differences in practice across geographical areas and are increasing the evidence base for interventions.14

Funding research

Controversies and future directions

Trainees are expected to undertake research during their training. Due to time constraints this encourages low level studies and biases against RCTs or Systematic Reviews. Supervisors should offer research training for trainees.

Trainees are expected to undertake research during their training. Due to time constraints this encourages low level studies and biases against RCTs or Systematic Reviews. Supervisors should offer research training for trainees. Most public hospital departments are poorly resourced both financially and with research-specific personnel to undertake research in emergencies in children. There is a pressing need for the development of university departments of paediatric emergency medicine.

Most public hospital departments are poorly resourced both financially and with research-specific personnel to undertake research in emergencies in children. There is a pressing need for the development of university departments of paediatric emergency medicine. The development of cross linkages through research networks such as PREDICT has helped build capacity in emergency departments. It has also provided increased exposure of paediatric emergency research to funding agencies which may be the basis for developing high level research studies with dissemination of both research projects and their results into more emergency departments.

The development of cross linkages through research networks such as PREDICT has helped build capacity in emergency departments. It has also provided increased exposure of paediatric emergency research to funding agencies which may be the basis for developing high level research studies with dissemination of both research projects and their results into more emergency departments.1 National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Levels of Evidence Guidelines. Available from: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines/consult/consultations/add_levels_grades_dev_guidelines2.htm [accessed 29.10.10]

2 National Institutes of Health. Office of Human Subjects Research. Regulations and Ethical Guidelines. Available from: http://ohsr.od.nih.gov/guidelines/nuremberg.html [accessed 29.10.10]

3 World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles of Medical Research involving Human Subjects. Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html [accessed 29.10.10]

4 National Institutes of Health. Office of Human Subjects Research. Regulations and Ethical Guidelines. Available from: http://ohsr.od.nih.gov/guidelines/belmont.html [accessed 29.10.10]

5 National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Research Council. Australian Vice Chancellors’ Committee. National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. 2007. Available from: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/PUBLICATIONS/ethics/2007_humans/contents.htm [accessed 29.10.10]

6 Therapeutics Goods Administration. Available from: www.tga.gov.au/docs/pdf/euguide/ich/ich13595.pdf [accessed 29.10.10]

7 Green J.B., Duncan R.E., Barnes G.L., Oberklaid F. Putting the ‘informed’ into ‘consent’: a matter of plain language. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39(9):700-703.

8 CONSORT group. The CONSORT Statement. Available from: http://www.consort-statement.org/consort-statement/ [accessed 29.10.10]

9 EQUATOR Network. Introduction to reporting guidelines. Available from: http://www.equator-network.org/resource-centre/library-of-health-research-reporting/reporting-guidelines/ [accessed 20.10.10]

10 . International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use’. ICH Guidelines. Available from: http://www.ich.org/cache/compo/276-254-1.html [accessed 29.10.10]

11 National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Research Council. Australian Vice Chancellors’ Committee. Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research. 2007. 2007. Available from: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/publications/synopses/r39.pdf [accessed 29.10.10]

12 International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals: Publishing and Editorial Issues Related to Publication in Biomedical Journals: Obligation to Register Clinical Trials. Available from: http://www.icmje.org/publishing_10register.html [accessed 29.10.10]

13 . Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry. Available from: www.anzctr.org.au [accessed 20.10.10]

14 Kuppermann N., Holmes J.F., Dayan P.S., et al. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374(9696):1160-1170.