Repair of Suburethral Diverticulum

For practical purposes, a suburethral diverticulum is any fluid-filled mass along the anterior lateral portions of the vagina that can be shown to have a direct communication with the urethra. Patients with a suburethral diverticulum may be asymptomatic or may complain of chronic recurrent cystitis, pain, burning and frequency, dyspareunia, voiding difficulty, postvoid dribbling, urinary incontinence, gross hematuria, or protrusion of a vaginal mass. Surgery should be considered only when the diverticulum becomes symptomatic.

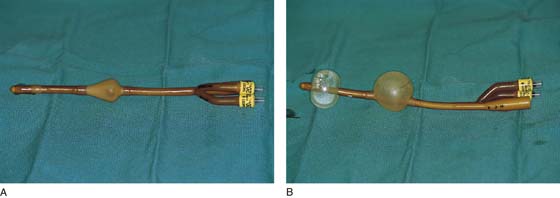

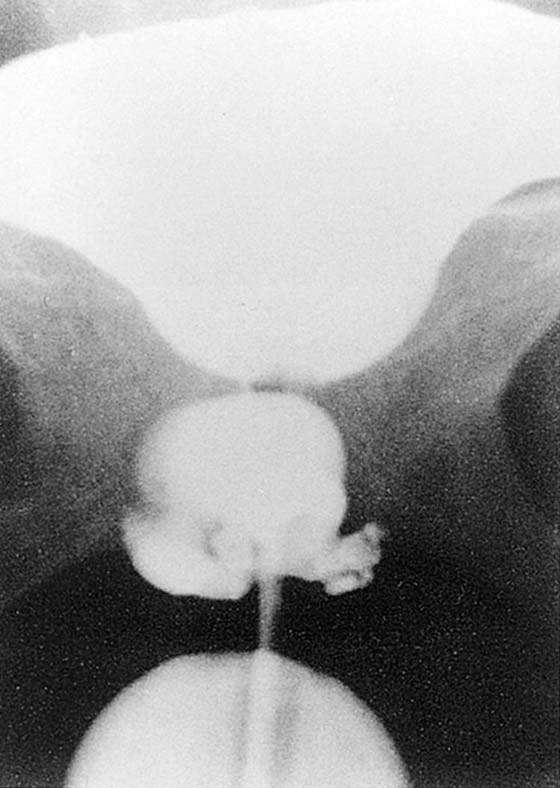

A Tratner double balloon catheter (Fig. 84–1A, B) is specially designed to assist in the diagnosis of a diverticulum, as well as in the identification and location of the diverticulum at the time of surgery. The catheter is composed of a proximal balloon that inflates within the bladder neck, anchoring the catheter, and a distal balloon that occludes the external meatus (see Fig. 84–1B). Contrast fills the urethra through a slit between the balloons. With this catheter, the urethra basically becomes a closed tube that can be injected with contrast medium under moderate pressure, permitting radiographic visualization of diverticula even with minute sinus tracts. This has been termed positive-pressure urethrography (Fig. 84–2).

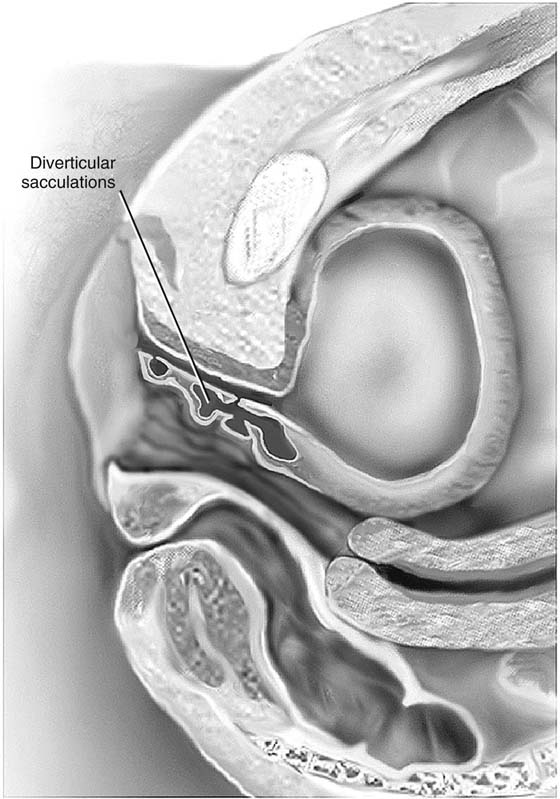

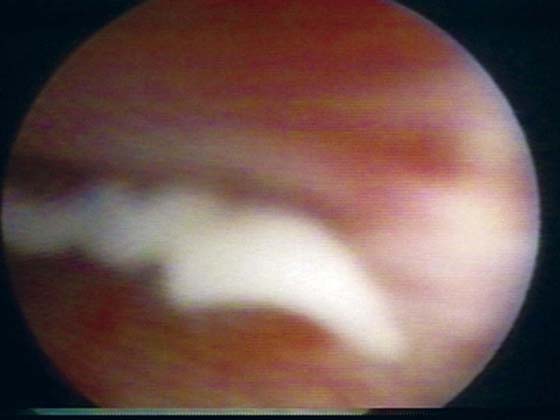

The degree of difficulty associated with repair of diverticula depends on their size and number (Fig. 84–3), the position of the ostium in relation to the bladder neck and trigone, and the degree of inflammation. Very commonly pus or discharge can be seen at the urethral meatus (Fig. 84–4) or in the urethra (Fig. 84–5) when anterior vaginal wall massage is performed. Large multiloculated or saddle-shaped diverticula in the proximal urethra or bladder neck region may require extensive dissection extending under the trigone (see Fig. 84–3). In these situations, preoperative placement of ureteral stents may facilitate identification of ureters and reduce the risk of damage during dissection. Some surgeons will routinely perform a suburethral sling at the time of repair of a diverticulum if they believe that the incontinence mechanism is going to be significantly compromised. In these situations, transposition of the labial fat pad between the repaired diverticulum and the suburethral sling should be performed (see Chapter 85, Martius Fat Pad Transposition and Urethral Reconstruction).

FIGURE 84–1 Tratner double balloon catheter. A. Note the deflated proximal and distal balloons. B. Inflation of the proximal and distal balloons makes the urethra a closed tube that could be injected with contrast medium under moderate pressure, permitting radiographic visualization of diverticula even with minute sinus tracts.

FIGURE 84–2 Positive-pressure urethrogram showing a large, multiloculated suburethral diverticulum. (From Walters MD, Karram MM: In Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, 2nd ed. CV Mosby, St Louis, 1999, with permission.)

FIGURE 84–3 The varied potential complexity of urethral diverticula. Note the small distal diverticulum, which if symptomatic could be treated with a Spence procedure, in contrast to a complex multiloculated proximal diverticulum.

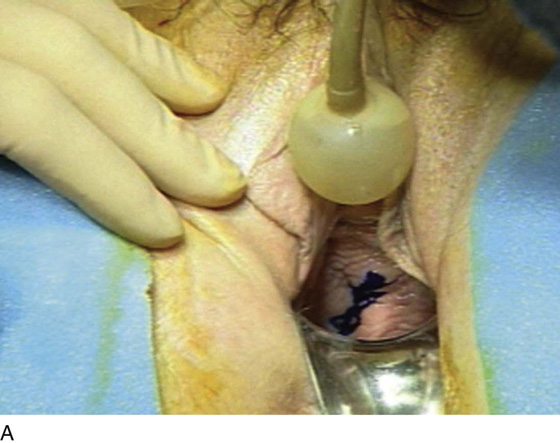

FIGURE 84–4 Anterior vaginal wall massage in a patient with an infected diverticulum produces a discharge from the urethral meatus.

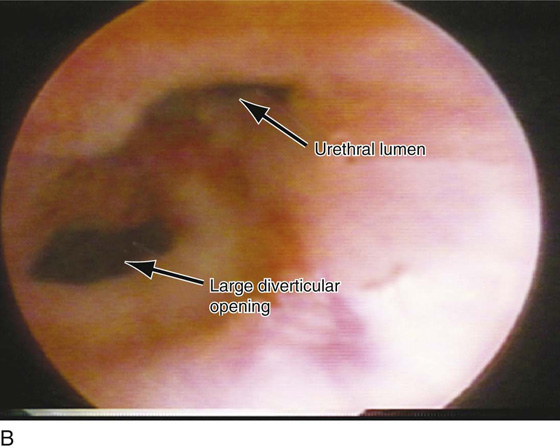

FIGURE 84–5 Urethroscopic view of diverticular opening. Note that puslike discharge is seen exiting the opening when anterior vaginal wall massage is performed.

Multiple methods have been described to surgically correct the suburethral diverticulum. The two most commonly performed techniques are diverticulectomy and the partial ablation technique. With both techniques, a “vest-over-pants” closure of the periurethral fascia is utilized to avoid overlapping sutures and thereby reduce the incidence of urethrovaginal fistula (Figs. 85–6 through 85–8).

Following is a step-by-step description of the techniques utilized to repair a urethral diverticulum:

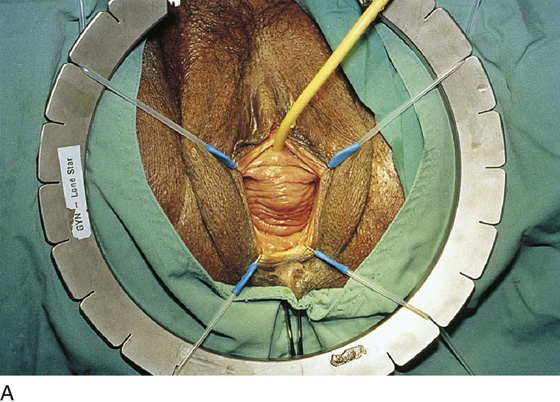

1. Usually regional or general anesthesia is utilized. Prophylactic antibiotics are generally given on call to the operating room. Cystourethroscopy is performed before surgery to localize the diverticular opening in the urethra and ensure that there are no other unsuspected findings. A double balloon catheter is placed, and the balloons are inflated proximally and distally. Sterile milk or methylene blue is injected into the catheter to inflate the urethra and the diverticulum. The author prefers to keep the catheter in place until the sac is entered, as it can be inflated periodically to assist in identification and mobilization of the sac off the vagina. Hydrodissection is utilized in the anterior vaginal wall to facilitate dissection in a proper plane.

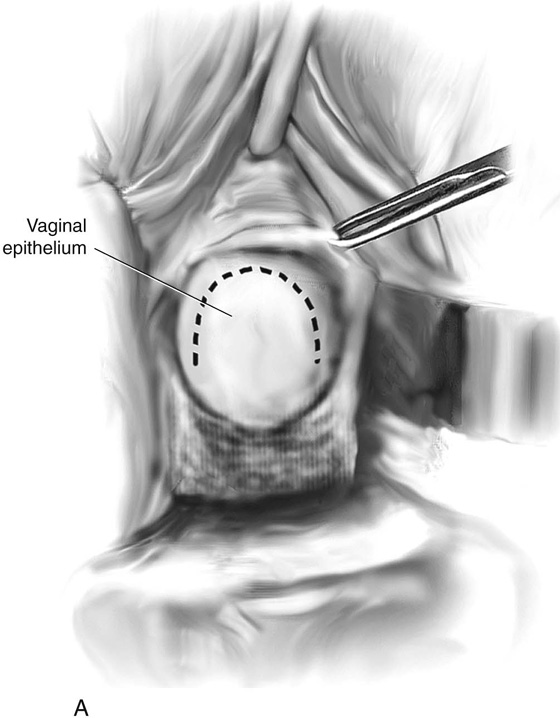

2. An inverted-U incision is made over the diverticulum in the vaginal epithelium, and the vaginal wall is sharply dissected off the urethra and periurethral fascia.

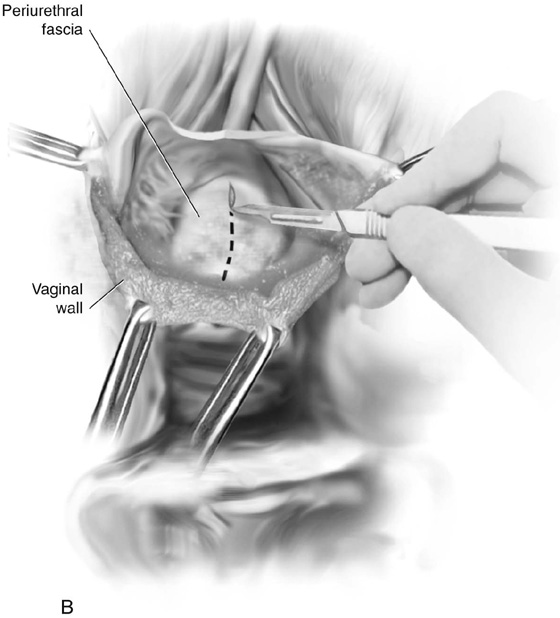

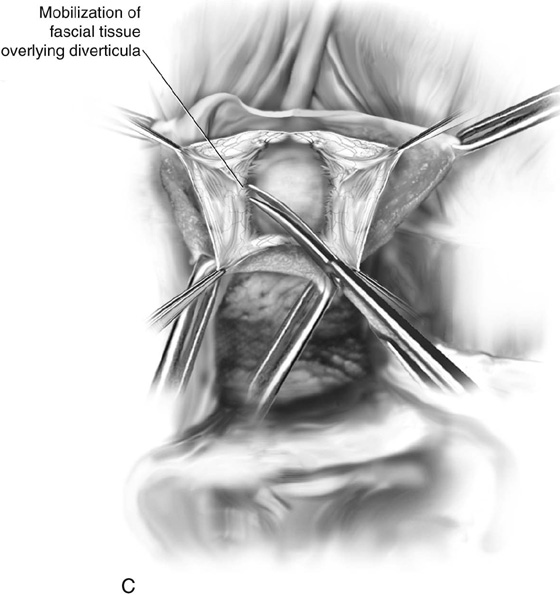

3. A longitudinal incision is made carefully over the diverticular sac. The fascial tissue overlying and surrounding the diverticulum is completely dissected and mobilized, thus creating two flaps of fascia that will be utilized for the “vest-over-pants” closure of the diverticulum.

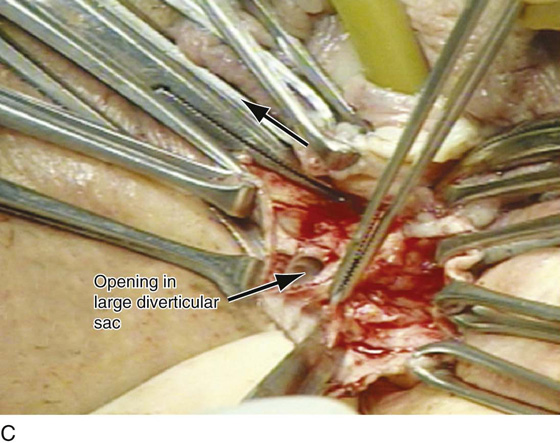

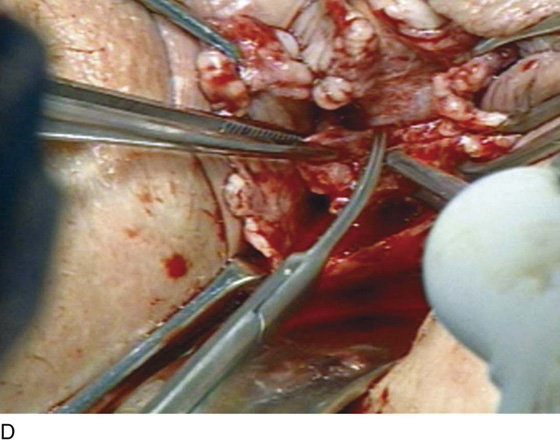

4. Dissection is continued around the sac until the neck is visualized. If the entire sac of the diverticulum is isolated, the diverticulum is excised from the urethra. If the sac cannot be mobilized, the sac is opened longitudinally and the inside of the diverticulum is explored to note the condition of the tissue and the presence of other diverticular openings, sacculations, or foreign bodies (see Figs. 84–5 and 84–6). If the base of the sac is firmly adherent to the urethra, a partial ablation technique is used to close off the opening of the urethra (see Fig. 84–6). If the sac can be completely excised at its neck, a complete diverticulectomy is performed and the urethral opening is closed longitudinally over a Foley catheter with interrupted fine delayed absorbable sutures (see Fig. 84–7).

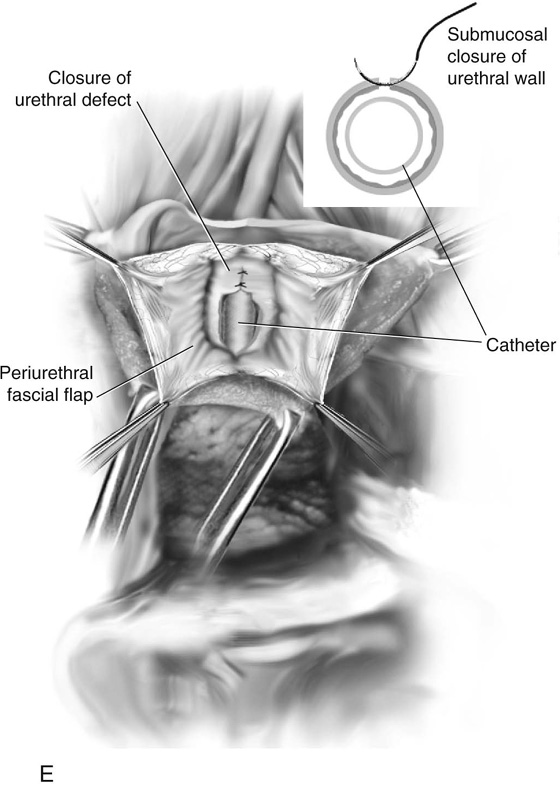

5. The periurethral fascia previously developed into flaps bilaterally is closed in a “vest-over-pants” fashion over the urethra. This maneuver avoids suture lines that overlap the urethral repair (see Figs. 84–6 and 84–7).

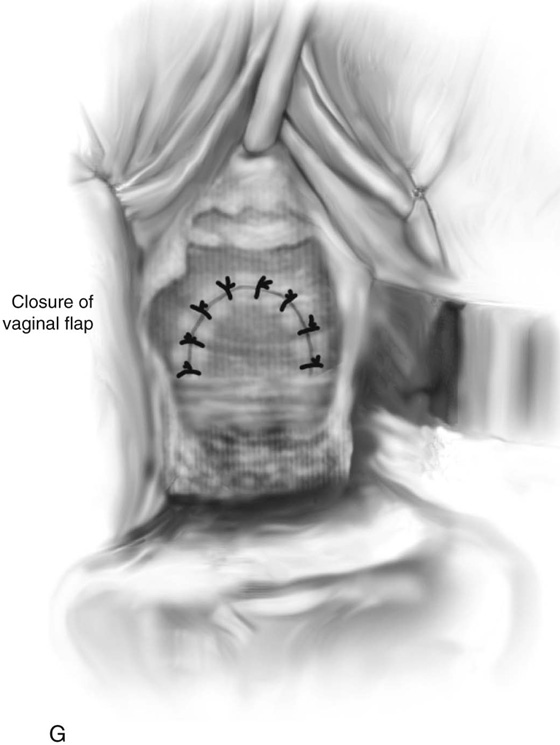

6. The flap of the vaginal epithelium is repositioned, and the incision is closed with a 2-0 absorbable interrupted suture. The author generally will pack the vagina for 24 hours and will utilize continuous transurethral Foley drainage for 7 to 10 days. Fig. 84–8 reviews the entire procedure with illustrations. Figs. 84–9 and 84–10 demonstrate two cases in which a calculus had formed in the diverticulum.

Thus the partial ablation technique is identical to that of diverticulectomy except that no effort is made to enucleate the sac at its neck or at the juncture with the urethra. The base and neck of the diverticulum are closed side-to-side using fine interrupted sutures, and then a second layer of similar sutures is placed that imbricates the previous urethral defect. Periurethral fascia is then sutured down in a “vest-over-pants” fashion in both techniques (see Fig. 84–8).

A Spence procedure can be used for diverticuli present in the distal urethra (distal to the area of maximum urethral closure pressure). This is basically a distal marsupialization in that one blade of a pair of scissors is placed in the urethra and the other in the vagina. The scissors divide the floor of the diverticulum and the overlying vaginal epithelium, including the posterior urethra distal to the diverticulum. Redundant flaps of diverticulum and vaginal epithelium are trimmed, and a running interlocking delayed absorbable suture coapts the margins of the remaining lining of the sac and adjacent vaginal epithelium.

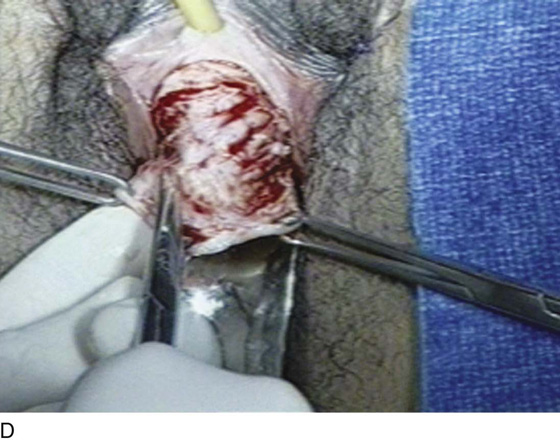

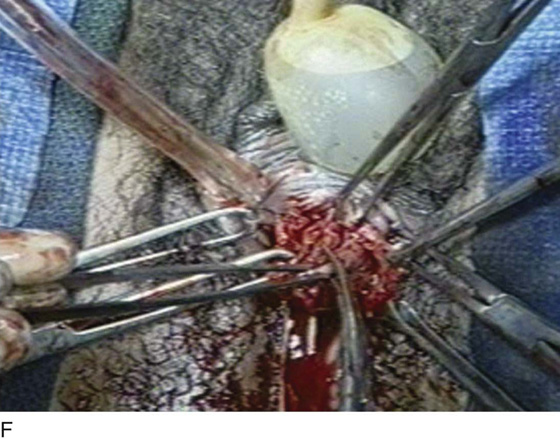

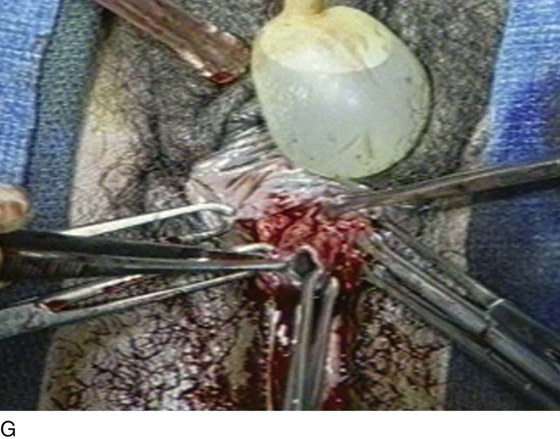

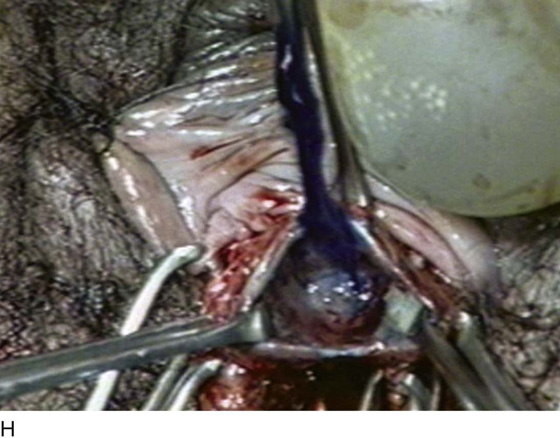

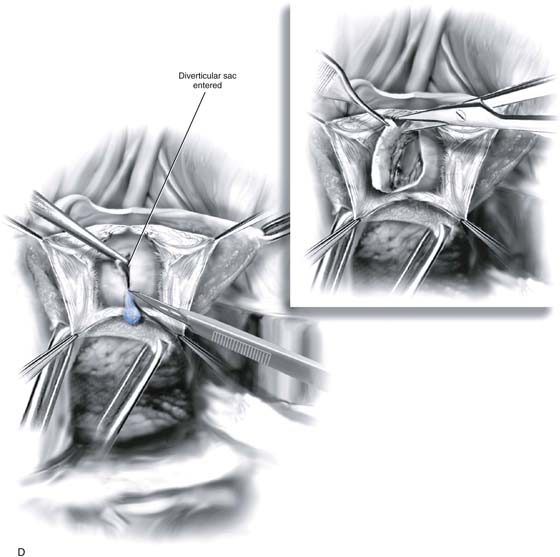

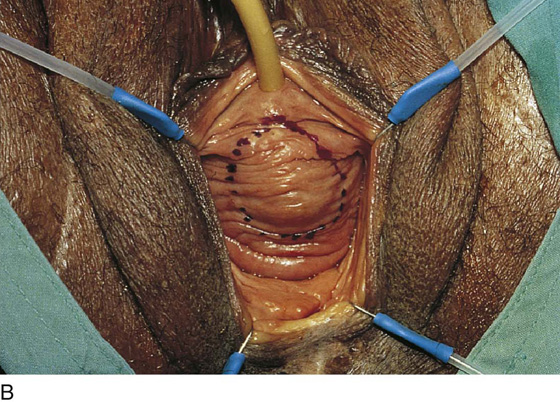

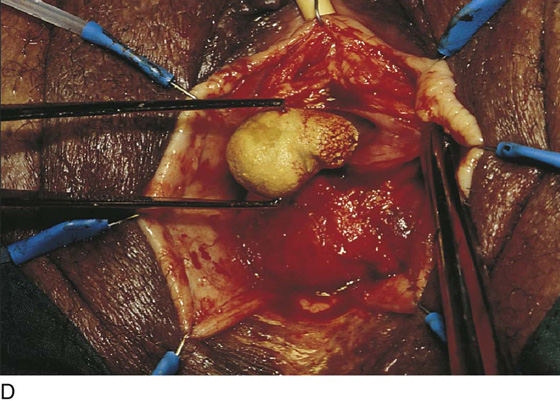

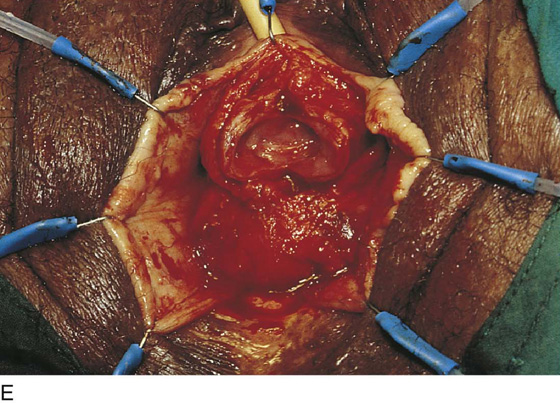

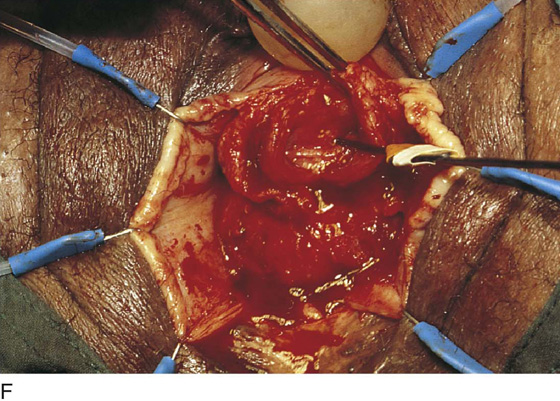

FIGURE 84–6 Urethral diverticulum with a small orifice opening into the urethra in which a partial ablation technique is the preferred surgical repair. A. Note that discharge is readily seen from the external urethral meatus with massage of the anterior vaginal wall. B. Note the very small opening of the urethral diverticulum into the midportion of the urethra when viewed urethroscopically. C. The large diverticulum is being outlined with a marking pencil. D. An inverted-U incision has been made on the anterior vaginal wall, and the vagina is sharply dissected off the underlying fascia. E. Periurethral flaps are being created that will facilitate closure of the defect in the urethra. F. The diverticular sac has been isolated and mobilized away from the periurethral fascia and is being sharply entered. G. The diverticular sac has been opened. H. Note the entire extent of the diverticular sac and a small diverticular opening into the urethra. Positive-pressure urethrography is utilized to demonstrate the spillage of dye from this orifice. Because the opening in the wall of the urethra is small, the sac will be excised and a partial ablation of the opening will be performed, followed by a “vest-over-pants” closure of the fascia that was previously mobilized.

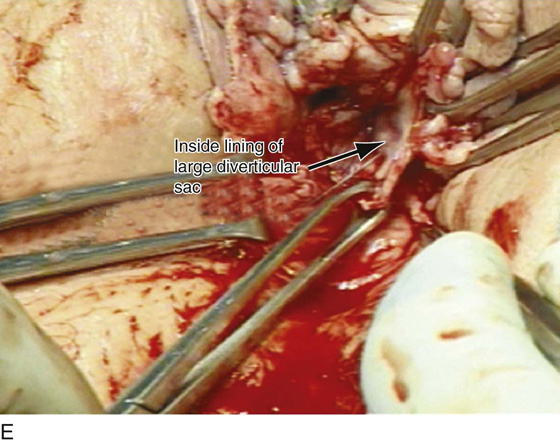

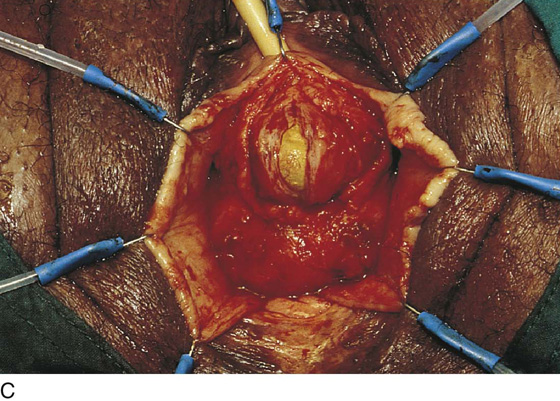

FIGURE 84–7 Large midurethral diverticulum. A. With positive-pressure urethrography, the diverticulum spontaneously ruptures into the anterior vaginal wall. B. Urethroscopic examination demonstrates a very large diverticular opening. C. The anterior vaginal wall has been opened, and spontaneous rupture in the diverticular sac is noted. D. The diverticular sac has been mobilized off the anterior vaginal wall and is being excised back to the large diverticular opening. E. Inside lining of the diverticular sac. Excision of this will complete the diverticulectomy, and the urethra will then be closed in layers, followed by a “vest-over-pants” closure of the periurethral fascia.

FIGURE 84–8 Technique of suburethral diverticulectomy with “vest-over-pants” closure of periurethral fascia. A. Inverted-U incision on the anterior vaginal wall. B. Complete mobilization of the anterior vaginal wall off the diverticular sac. A longitudinal incision is made in the wall of the diverticulum. C. Sharp dissection creates two flaps of periurethral fascia. D. The diverticular sac is sharply entered and the wall of the sac is trimmed. E. The diverticular sac has been excised and the defect in the urethra is closed in a submucosal fashion with fine interrupted delayed absorbable sutures. F. Periurethral fascia is laid down in a “vest-over-pants” fashion. G. The anterior vaginal wall incision is closed.

FIGURE 84–9 Suburethral diverticulum in which a calculus has developed. A. Exposure of the anterior vaginal wall. B. The location of the diverticulum has been marked. C. The anterior vaginal wall has been mobilized off the diverticular sac, two flaps of periurethral fascia have been created, and the diverticulum has been opened exposing a calculus. D. The calculus is shown being removed from the diverticulum. E. The edges of the sac have been trimmed back in preparation for partial ablation closure of the defect. Note the dissected flaps of periurethral fascia, which will be laid down in a “vest-over-pants” fashion. F. Probe is passed into an opening in the diverticular sac that communicates with the urethra.

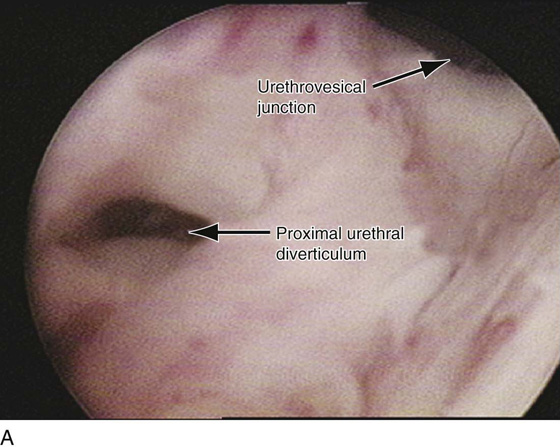

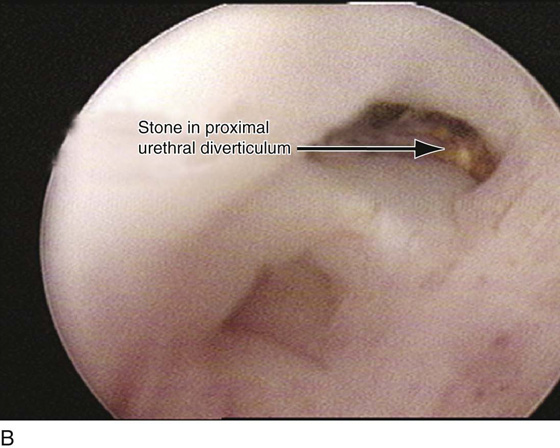

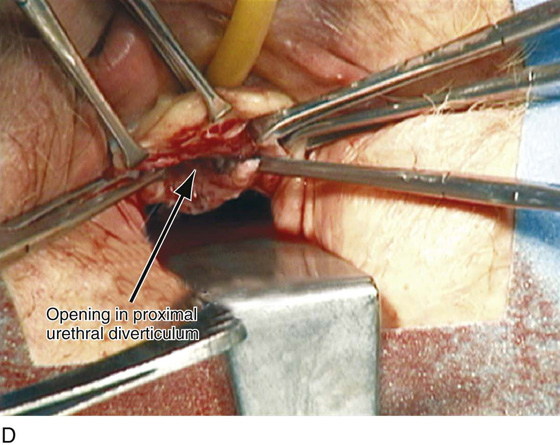

FIGURE 84–10 Proximal urethral diverticulum with a calculus in the diverticulum. A. Note the proximal opening of the diverticulum as it relates to the urethrovesical junction. B. Urethroscopic view of the calculus in the diverticular sac. C. The diverticulum has been opened vaginally, and the stone has been removed. D. The opening in the proximal urethral diverticulum is noted.