CHAPTER 7 RENAL SYSTEM

RENAL DYSFUNCTION IN CRITICAL ILLNESS

Classically, the causes of acute renal dysfunction are divided into prerenal (inadequate perfusion), renal (intrinsic renal disease) and postrenal (obstruction). These are summarized in Box 7.1.

Box 7.1 Causes of renal dysfunction*

| Pre-renal | Renal | Post renal |

|---|---|---|

| Dehydration | Renovascular disease | Kidney outflow obstruction |

| Hypovolaemia | Autoimmune disease | Ureteric obstruction |

| Hypotension | SIRS and sepsis | Bladder outlet obstruction (blocked catheter) |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | ||

| Crush injury (myoglobinuria) | ||

| Nephrotoxic drugs |

* In many patients the cause of renal failure will be multifactorial.

Three terms are commonly used in relation to different patterns of renal dysfunction/failure

INVESTIGATION OF ACUTE RENAL DYSFUNCTION

History and examination

Investigations

Serum urea, electrolytes and creatinine

Serial measurements are used to monitor renal function and predict the need for renal replacement therapy. Avoid placing undue significance on single results. Take serial samples and look at trends.

Urinary biochemistry

As ATN develops, the renal tubules are no longer able to function normally, and are unable to retain sodium or concentrate the urine. The urinary sodium rises, urinary osmolality falls, and the urine to plasma urea ratio also falls. Eventually the urinary sodium and osmolality approach that of plasma. Renal tubular debris or casts may be seen in the urine. The distinguishing features of prerenal and renal failure are summarized in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1 Distinguishing features of prerenal and renal failure

| Prerenal | Renal (ATN) | |

|---|---|---|

| Urinary sodium* | <10 mmol/L | >30 mmol/L |

| Urinary osmolality* | High | Low |

| Urine: plasma urea ratio | >10:1 | <8:1 |

| Urine microscopy | Normal | Tubular casts |

* If patients have received diuretics, urinary sodium and osmolality are difficult to interpret.

Other investigations may be indicated depending on circumstances:

Creatine kinase (CK)/urinary myoglobin.

A raised serum creatine kinase and raised urinary myoglobin (early sign only) are indicative of rhabdomyolysis, for example following trauma, crush injury (see Rhabdomyolysis, p. 320.)

Vasculitis screen.

Renal disease may be associated with autoimmune conditions and vasculitis. An autoimmune/vasculitis screen may be appropriate, particularly in the presence of coexisting pulmonary disease. Seek advice. Investigations are listed in Table 7.2.

Table 7.2 Investigations for autoimmune disease in renal failure

| Vasculitis | Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) |

|---|---|

| Goodpasture’s syndrome | Antiglomerular basement membrane antibodies |

| Systemic lupuserythematosus (SLE) | Antinuclear antibodies (ANA)Anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies |

| Rheumatoid disease | Rheumatoid factor |

OLIGURIA

Review the biochemistry results. Is there evidence of deteriorating renal function over time (i.e. increasing serum urea and creatinine)?

Review the biochemistry results. Is there evidence of deteriorating renal function over time (i.e. increasing serum urea and creatinine)? Review the clinical status of the patient. Is there evidence of dehydration/hypovolaemia suggested by: thirst, poor tissue turgor (pinch skin on back of hand), dry mouth, cool pale limbs, large respiratory swing on arterial line, low CVP or low stroke volume index?

Review the clinical status of the patient. Is there evidence of dehydration/hypovolaemia suggested by: thirst, poor tissue turgor (pinch skin on back of hand), dry mouth, cool pale limbs, large respiratory swing on arterial line, low CVP or low stroke volume index?MANAGEMENT

If there is evidence of hypovolaemia, give a fluid challenge. Even if the patient is apparently normovolaemic it is generally worth giving a fluid challenge (e.g. 500 mL colloid). Any response may not be immediate. If there is no response consider the need for invasive monitoring to further assess volume status.

If there is evidence of hypovolaemia, give a fluid challenge. Even if the patient is apparently normovolaemic it is generally worth giving a fluid challenge (e.g. 500 mL colloid). Any response may not be immediate. If there is no response consider the need for invasive monitoring to further assess volume status. Renal filtration is a pressure-dependent process. Elderly patients, in particular, those with hypertensive vascular disease, may require a higher than expected mean blood pressure. Consider the use of inotropes or vasopressors as appropriate to increase blood pressure towards the normal or preadmission blood pressure for the patient.

Renal filtration is a pressure-dependent process. Elderly patients, in particular, those with hypertensive vascular disease, may require a higher than expected mean blood pressure. Consider the use of inotropes or vasopressors as appropriate to increase blood pressure towards the normal or preadmission blood pressure for the patient. If the cause of the oliguria is not clear from clinical evaluation and there is no response to simple measures, consider further investigations as above.

If the cause of the oliguria is not clear from clinical evaluation and there is no response to simple measures, consider further investigations as above. Review the prescription chart. Decide whether to stop any potentially nephrotoxic drugs (aminoglycosides, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, immunosuppressant agents).

Review the prescription chart. Decide whether to stop any potentially nephrotoxic drugs (aminoglycosides, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, immunosuppressant agents). If the patient remains oliguric, give bumetanide 1–2 mg bolus i.v. or furosemide (frusemide) 20–40 mg bolus i.v. (bumetanide may be preferable to furosemide, as it does not need to be filtered by the glomerulus to achieve its effect). If there is a response, consider the use of an infusion to maintain urine output: bumetanide 1–2 mg/h or furosemide 20–40 mg/h.

If the patient remains oliguric, give bumetanide 1–2 mg bolus i.v. or furosemide (frusemide) 20–40 mg bolus i.v. (bumetanide may be preferable to furosemide, as it does not need to be filtered by the glomerulus to achieve its effect). If there is a response, consider the use of an infusion to maintain urine output: bumetanide 1–2 mg/h or furosemide 20–40 mg/h. If there is no response, consider high-dose diuretics, e.g. bumetanide 5 mg or furosemide 250 mg over 1 h, followed, if there is a response, by an infusion.

If there is no response, consider high-dose diuretics, e.g. bumetanide 5 mg or furosemide 250 mg over 1 h, followed, if there is a response, by an infusion.ACUTE RENAL FAILURE

Oliguric renal failure

Inability to excrete fluid may result in progressive fluid overload. This may be manifest as hypertension, tissue and pulmonary oedema.

Inability to excrete fluid may result in progressive fluid overload. This may be manifest as hypertension, tissue and pulmonary oedema. Impaired acid–base balance results in progressive accumulation of hydrogen ions and metabolic acidosis. This may be exacerbated by the effects of excess chloride load (from use of 0.9% sodium chloride containing fluids) resulting in hyperchloraemic acidosis (see hyperchloraemic acidosis, p. 53).

Impaired acid–base balance results in progressive accumulation of hydrogen ions and metabolic acidosis. This may be exacerbated by the effects of excess chloride load (from use of 0.9% sodium chloride containing fluids) resulting in hyperchloraemic acidosis (see hyperchloraemic acidosis, p. 53).Control of hyperkalaemia

The main concern in the acute phase is the development of ventricular dysrhythmias associated with hyperkalaemia. Potassium levels can rise quickly in the presence of severe sepsis and hypercatabolism. Patients with chronic renal failure (CRF) may tolerate hyperkalaemia much better than patients with ARF. A serum potassium greater than 6–6.5 mmol/L requires urgent treatment. Calcium, bicarbonate and dextrose/insulin buy time prior to dialysis but do not alter the underlying problem. (See Hyperkalaemia, p. 206.)

Indications for renal replacement therapy (RRT)

Typical indications for instituting renal replacement therapy in acute renal failure are shown in Box 7.2.

| Acute | Within 24 h |

|---|---|

| K+ > 6.5 mmol/L | Urea > 40–50 mmol/L and rising* |

| pH < 7.2 | Creatinine > 400 μmol/L and rising* |

| Fluid overload/pulmonary oedema | Hypercatabolism, severe sepsis |

RENAL REPLACEMENT THERAPY

Intermittent haemodialysis is associated with significant haemodynamic instability in critically ill patients. Continuous renal replacement systems that allow more gradual correction of biochemical abnormalities and removal of fluid are therefore preferred, at least during the acute phase of the illness. These systems also have the advantage that they can be safely used outside specialist renal dialysis centres.

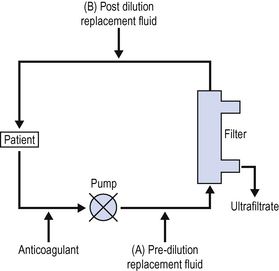

Continuous venovenous haemofiltration (CVVHF)

The simplest form of continuous renal replacement is continuous venovenous haemofiltration (Fig. 7.1).

There has been a great deal of interest recently in the role of CVVHF in sepsis. Many of the proinflammatory molecules, toxins and cytokines, which are implicated in the pathogenesis of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome, are removed by haemofiltration. There is anecdotal evidence that some unstable patients have improved following the institution of CVVHF and many units now routinely haemofilter septic patients. There is some limited evidence that high volume haemofiltration, e.g. 2000 mL/h may stabilize the critically ill septic patient. (See Sepsis, p. 331.)

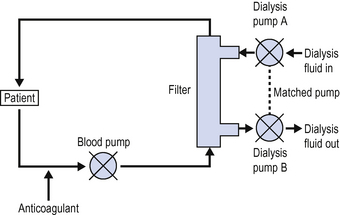

Continuous venovenous haemodialysis (CVVHD)

In continuous haemodialysis (Fig. 7.2), dialysis fluid is passed over the filter membrane in a countercurrent manner. Fluids, electrolytes and small products can move in both directions across the filter, depending on hydrostatic pressure, ionic binding and osmotic gradients. Overall creatinine clearance is greatly improved compared with haemofiltration alone.

In CVVHD, provided the volume of dialysis fluid passing out from the system matches the volume of dialysis fluid passing in, there is no net gain or loss of fluid to the patient. By allowing more dialysate fluid to pass out of the filter than passes in, fluid can be effectively removed from the patient. Rates of fluid removal up to 200 mL/h can be achieved. In most CVVHD machines fluid removal is achieved by increasing the rate of the dialysis pump controlling the exit side of the filter by the amount of fluid to be removed (Fig. 7.2).

PERITONEAL DIALYSIS

Peritoneal dialysis is commonly used in children and adults for the management of CRF. In children it is frequently also used in the management of ARF because of the difficulties of venous access. The potential advantages of peritoneal dialysis over other forms of renal replacement therapy are shown in Box 7.4.

MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH CHRONIC RENAL FAILURE

Patients with chronic dialysis dependent renal failure (CRF) may present to the ICU with intercurrent disease. The principles for managing these patients are very similar to those for managing patients with ARF. These patients, however, have a number of specific problems (Box 7.5).

PRESCRIBING IN RENAL FAILURE

Prescribing drugs to patients in renal failure is therefore a complex issue, and you should seek advice from your pharmacist and/or renal physicians. Where possible, nephrotoxic drugs should be avoided and alternative agents prescribed. Where either no alternative exists or none is suitable, close monitoring (e.g. of plasma levels) may be required and the risks and benefits of continuing treatment considered daily. A list of commonly prescribed nephrotoxic drugs is given in Box 7.6.

The dose and/or frequency of many drugs vary according to the renal function, based on estimates of creatine clearance. The most commonly used formula for calculating creatinine clearance is the Cockcroft–Gault formula, shown in Box 7.7.

Box 7.7 Cockcroft–Gault formula for estimating creatinine clearance

For females multiply by 0.85.

Drug clearance during RRT

For the purpose of prescribing, creatinine clearance during renal replacement therapy can be considered as being greatly reduced. (< 10 mL/min). Drug clearance is dependent on molecular size, charge, volume of distribution and water solubility. In general, non-ionized drugs with high fat solubility and large volume of distribution will not be cleared efficiently by dialysis (e.g. CNS-acting sedative and analgesic drugs).

Antibiotics

The clearance of aminoglycosides is reduced in renal failure, and high levels are both nephrotoxic and cause deafness if maintained over time. Reduce the dosage/frequency and monitor levels (see Appendix 1, p. 449). Penicillins may accumulate and produce seizures at high concentrations. Dose and frequency should be reduced after loading doses have been given. Carbipenems, cephalosporins and other antibiotics may also need dose reduction. Seek advice.

PLASMA EXCHANGE

Plasma exchange is a therapy used in some acute, immune mediated conditions to reduce the load of circulating immunologically active proteins. Simplistically, plasma containing such active proteins is removed and its volume replaced with 4.5% albumin solution or FFP. There are a number of established indications and it is occasionally used in ICU patients (Box 7.8).

Box 7.8 Indications for plasma exchange

| Established indications include: | Speculative uses include: |

|---|---|

| Guillain–Barré syndrome | Severe sepsis |

| Myasthenia gravis | Pancreatitis |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Other vasculitis (e.g. Goodpasture’s syndrome) | |

| Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP–HUS) |